3

Individuals within Social Contexts

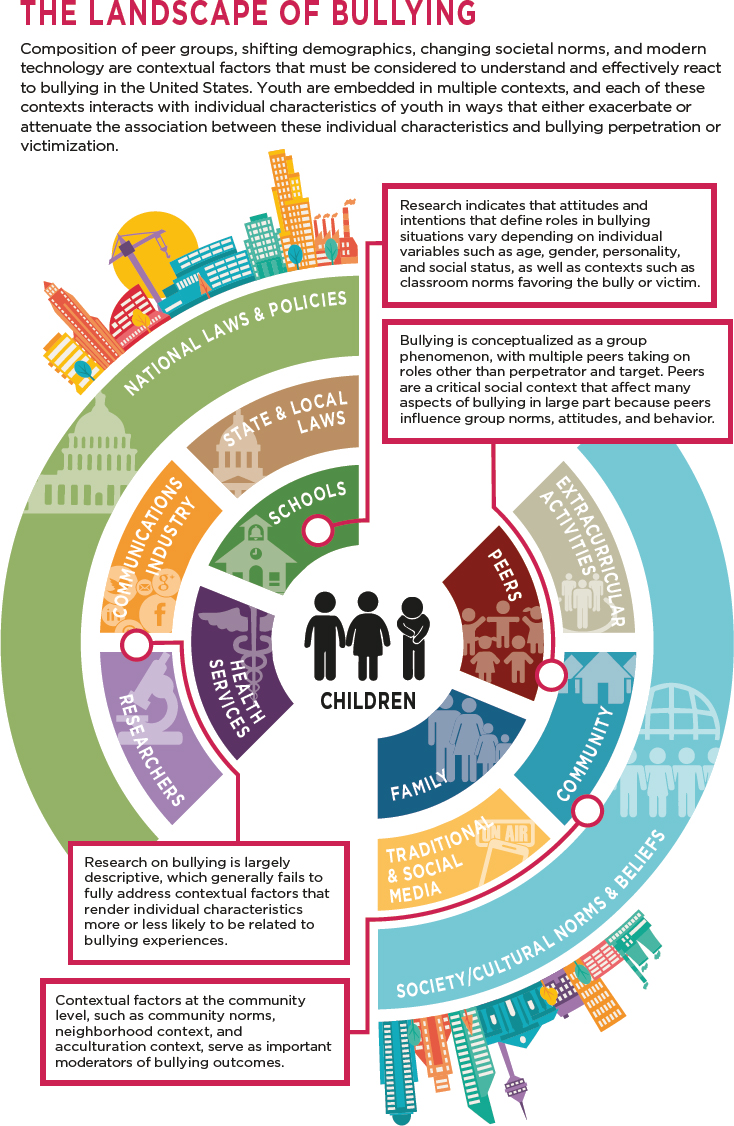

To date, research on bullying has been largely descriptive. These descriptive data have provided essential insights into a variety of important factors on the topic of bullying, including prevalence, individual and contextual correlates, and adverse consequences. At the same time, the descriptive approach has often produced inconsistencies—for example, some descriptive studies on racial/ethnic differences in those who are bullied found that African Americans are more bullied than Latinos (Peskin et al., 2006), whereas others found no group differences (Storch et al., 2003). Such inconsistencies are due, in part, to lack of attention to contextual factors that render individual characteristics such as race/ethnicity more or less likely to be related to bullying experiences. Consequently, there has been a call to advance the field by moving from descriptive studies to an approach that identifies processes that can explain heterogeneity in bullying experiences by focusing on contextual factors that modulate the effect of individual characteristics (e.g., ethnicity, gender, age, sexual orientation) on bullying behavior (Hong et al., 2015; Swearer and Hymel, 2015).

Such an approach is not new. In fact, it has long been recognized that individuals are embedded within situations that themselves are embedded within broader social contexts (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). Whereas a situation refers to “a particular concrete physical and social setting in which a person is embedded at any one point in time,” context is “the surround for situations (and individuals in situations). Context is the general and continuing multilayered and interwoven set of material realities, social structures, patterns of social relations, and shared belief systems that surround any given situation” (Ashmore et al., 2004, p. 103). This “person by situation by con-

text” interaction has been applied to personality (Mischel and Shoda, 1995) and to social characteristics; for example, collective identities (Ashmore et al., 2004), but it also applies to bullying. For instance, a gay student may be bullied in the locker room following gym class. But this particular situation (i.e., locker room after gym class) occurs within a broader social context, such as whether anti-bullying laws include sexual orientation as an enumerated group and whether the surrounding community views homosexuality as a normal or deviant expression of sexuality. These contextual factors influence the manner in which this situation unfolds. Some of these social contexts are far more likely to prevent the bullying of the gay youth from occurring or to buffer the negative effects more effectively if the bullying occurs.

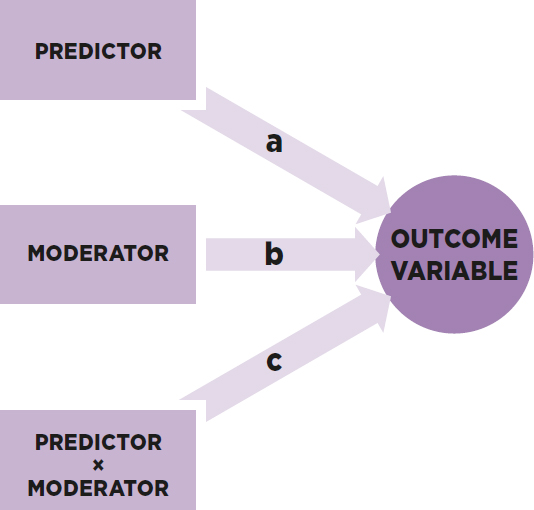

This chapter is organized around social contexts that can either attenuate or exacerbate (i.e., moderate) the effect of individual characteristics on bullying behavior. Thus, it moves beyond current descriptions of contextual correlates of bullying—which examine main effect relations between a contextual factor, such as schools, and a bullying outcome, such as perpetration—to identify contextual moderators of individual characteristics on bullying and related outcomes. Doing this requires analyses that specifically examine moderation (a moderator analysis), or effect modification. A moderator is defined as a “qualitative (e.g., sex, race, class) or quantitative (e.g., level of reward) variable that affects the direction and/or strength of the relation between an independent or predictor variable and a dependent or criterion variable” (Baron and Kenny, 1986, p. 1174).1 Moderators can either magnify or diminish the association between the independent and dependent variables. For instance, if a study shows that adolescent girls develop depressive symptoms following interpersonal stressors, whereas adolescent boys do not, this would provide evidence that sex moderates the relationship between interpersonal stressors and depressive symptoms. Figure 3-1 illustrates a moderator model with three causal paths (a, b, c) that lead to an outcome variable of interest.

Why a focus on moderators? Prevention science is based on a fundamental assumption that a “careful scientific review of risk and protective factors for a given condition or impairment must be undertaken before the prevention trial is designed” (Cicchetti and Hinshaw, 2002, p. 669). Moderators help with specificity and precision in that they afford researchers the ability to “make precise predictions regarding the processes that guide behavior and, in particular, to specify explicitly the conditions under which

___________________

1 A variable functions as a mediator “to the extent that it accounts for the relation between the predictor and the criterion” (Baron and Kenny, 1986, p. 1176). Mediators are distinguished from moderators as they address how or why certain effects occur, whereas moderators explain when certain effects hold (Baron and Kenny, 1986).

SOURCE: Adapted from Baron and Kenny (1986, Fig. 1, p. 1174).

these processes operate” (Rothman, 2013, p. 190). In other words, before one can influence pathways in a positive direction, one must first understand the factors that increase the risk of poorer outcomes, as well as the factors that mitigate this risk.

The committee first discusses conceptual frameworks that underpin our approach. We then present illustrative examples across a variety of different social contexts—peers, families, schools, communities, and broad macrosystems—to demonstrate the utility of such an approach and to offer guidance for the field of bullying studies moving forward. The chapter ends with an outlining of areas that warrant greater attention in future research, as well as the committee’s findings and conclusions.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORKS

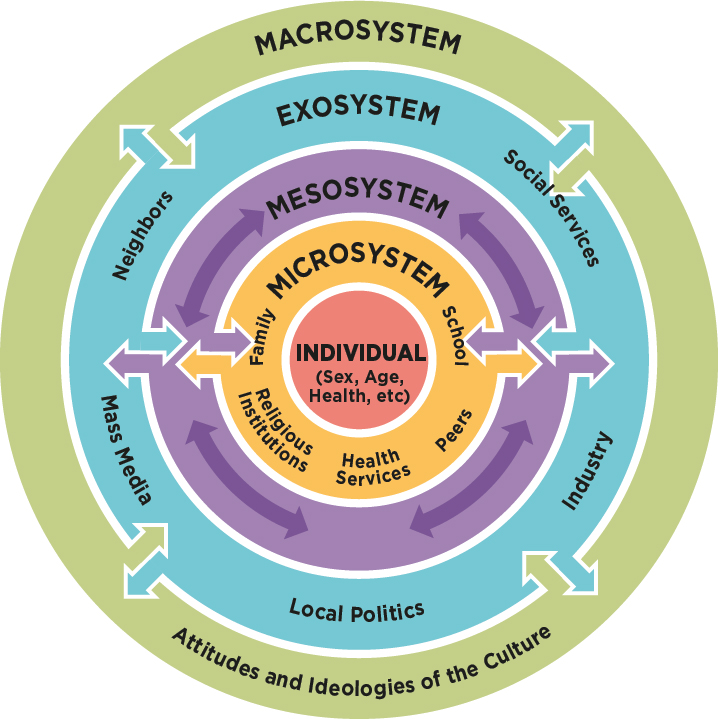

This chapter largely draws upon two theoretical and conceptual frameworks that have been frequently used in the bullying literature: the ecological theory of development and the concepts of equifinality and multifinality. Although these concepts and theories differ in focus, they share the overarching point that people are embedded in contexts that modulate the effect

of individual characteristics on developmental, social, and health outcomes. This insight is key to understanding how different social contexts affect the extent to which youths’ individual characteristics (e.g., gender, age, race/ethnicity, and sexual orientation) are associated with bullying perpetration or being bullied. Later in this chapter, the committee draws on a third conceptual framework—namely, stigma2—that has received comparatively less attention in the bullying literature but that we believe provides an important framework for understanding both the disparities in rates of bullying and in types of bullying (i.e., bias-based bullying) that have been observed in the literature.

Ecological Theory of Development

Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) bioecological model, which highlights the transactional nature of multiple levels of influence on human development, conceptualizes humans as nested within four levels (see Figure 3-2). The most proximal system is the microsystem (e.g., school, family), which includes immediate surroundings that more directly affect the individual. The next level of influence, the mesosystem, describes how the different parts of a child’s microsystem interact together. The exosystem includes neighborhoods or school systems. The macrosystem includes the broad norms and trends in the culture and policies, which impact development and behavior.

This ecological model has been applied to bullying (Swearer and Espelage, 2004; Swearer and Hymel, 2015; Swearer et al., 2010), providing a comprehensive framework in which to understand bullying in particular and peer victimization more generally. This application illustrates the interaction of intrapersonal, family, school, peer, and community characteristics that may influence victimization and in turn modulate the risk for adjustment and behavioral problems.

For example, the microsystem of the classroom, the family, or the peer group has been correlated with experiences of bullying behavior (Card et al., 2007). Risk factors and protective factors within the mesosystem, which can act as moderators, may include interacting microsystems such as parent-teacher relationships; however, few studies have jointly examined the influence of such risk and protective factors (Card et al., 2008). Several studies have examined risk factors for bullying behavior within the exosystem, such as urbanicity of school setting or other school-level indicators

___________________

2 As noted in the recent National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report, Ending Discrimination Against People with Mental and Substance Use Disorders: The Evidence for Stigma Change (2016), some stakeholder groups are targeting the word “stigma” itself and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) is shifting away from the use of this term. The committee determined that the word stigma was currently widely accepted in the research community and uses this term in the report.

SOURCE: Adapted from Bronfenbrenner (1979).

of concentrated disadvantage or school climate (Bradshaw and Waasdorp, 2009; Gregory et al., 2010; Wang and Degol, 2015). Others address the macrosystem, including a focus on anti-bullying legislation (Hatzenbuehler and Keyes, 2013; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2015a). More recent evolutions of the ecological model have now layered on the chronosystem, which characterizes the broader historical and temporal context in which an individual is embedded. For example, recent increases in the use of mobile technologies and the Internet (Lenhart et al., 2008) resulted in a novel contextual influence for today’s youth, whereas previous generations of adolescents did not have such experiences (Espelage et al., 2013).

In summary, the ecological model provides a framework from which to

further understand the influence that social contexts may have on both rates of bullying behavior and individuals’ experiences of negative outcomes, including mental health outcomes. By incorporating multiple levels of influence to explain and predict individual outcomes, the ecological model allows for a broader conceptualization of the various contextual influences on youth bullying.

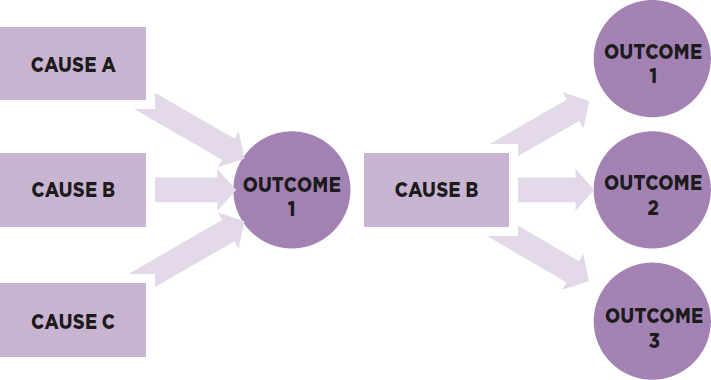

Equifinality and Multifinality

The complex interplay of risk, protection, and resilience resulting from different contextual influences explains why there is variation in the adjustment and developmental outcomes of children who are bullied, such as why not all youth who are bullied develop adjustment problems. This idea is highlighted in Cicchetti and Rogosch’s (1996) equifinality and multifinality theory of developmental psychopathology. There is considerable variability in processes and outcomes, and this variability is linked to varied life experiences that contribute to adaptive and maladaptive outcomes. In the case of equifinality, the same outcome—such as being an individual who bullies or an individual who is bullied—may derive from different pathways. For example, Haltigan and Vaillancourt (2014) found that for some youth, the pathway to bullying others began with being targeted by peers, while for others the pathway was initiated with low levels of bullying others. But the end result of these two diverse trajectories is the same: bullying perpetration. In the case of multifinality, instances that start off on a similar trajectory of bullying perpetration or peer victimization can result in vastly different outcomes. Figure 3-3 provides a schematic representation of these two concepts.

As an example, Kretschmer and colleagues (2015) examined maladjustment patterns among children exposed to bullying in early and mid-adolescence and found evidence for multifinality. That is, bullied youth experienced a variety of mental health outcomes as a function of being bullied, including problems with withdrawal/depression, anxiety, somatic complaints, delinquency, and aggression. However, when these varied outcomes were considered together, internalizing problems (withdrawal and anxiety) were the most common outcome.

The idea that there is diversity in “individual patterns of adaptation and maladaptation” is consistent with the current state of knowledge concerning involvement with bullying (Cicchetti and Rogosch, 1996, p. 599). For instance, in the Haltigan and Vaillancourt (2014) study, joint trajectories of bullying perpetration and being targeted for bullying across elementary school and middle school were examined and four distinct trajectories of involvement were noted. In the first group, there was low-to-limited

SOURCE: Illustration of concept proposed by Cicchetti and Rogosch (1996).

involvement in perpetration or in being a target for bullying.3 In the second group, involvement in bullying perpetration increased over time, and in the third group, being a target of bullying decreased over time. In the fourth group, a target-to-bully trajectory was found, which was characterized by decreasing rates of being targeted and increasing perpetration rates. The mental health outcomes associated with these distinct trajectories of bullying involvement also varied. Mental health problems in high school were particularly pronounced for children who were bullied in elementary school but were not bullied in middle school and for those who started off as targets of bullying and became bullies over time (Haltigan and Vaillancourt, 2014). These findings are consistent with a growing body of literature demonstrating the enduring effects of being bullied, effects that seem to last well into adulthood (Kljakovic and Hunt, 2016; McDougall and Vaillancourt, 2015).

PEERS

Peers are a critical social context that affect many aspects of bullying in large part because peers influence group norms, attitudes, and behavior

___________________

3Haltigan and Vaillancourt (2014) used the terms “peer victimization” or “victimization” to refer to the role of being bullied in bullying incidents (in the terminology preferred for this report, the “target” role in the bullying dyad).

(Faris and Felmlee, 2014; Vaillancourt et al., 2010; Veenstra et al., 2013). This section discusses research related to peers as a social context.

Multiple Participant Roles in Bullying

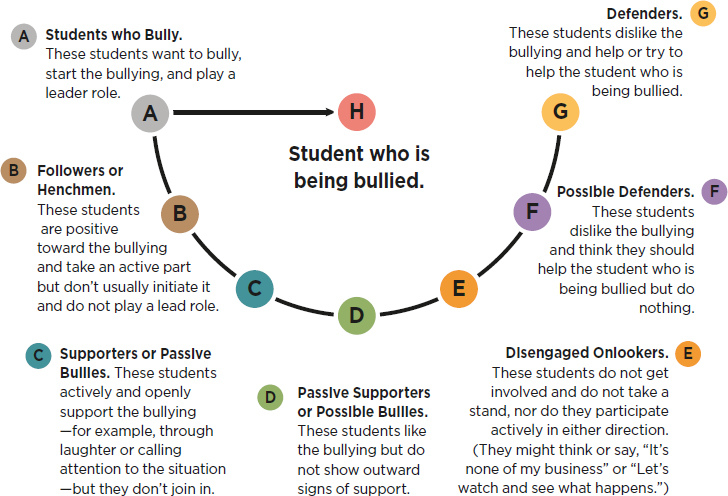

To acknowledge this larger peer context, bullying can be conceptualized as a group phenomenon, with multiple peers taking on roles other than perpetrator and target (Olweus, 1993; Salmivalli, 2001, 2010, 2014). Acknowledging the group context is particularly important, given what is known about the causes of bullying. Contemporary theory and research suggest that individuals who bully others are largely motivated to gain (or maintain) high status among their peers (see review in Rodkin et al., 2015). Because status such as popularity, dominance, visibility, and respect are attributes assigned by the group, individuals who bully need spectators to confer that status (Salmivalli and Peets, 2009). Observational studies have documented that witnesses are present in about 85 percent of bullying episodes (Hawkins et al., 2001; Pepler et al., 2010).

Witnesses to bullying take on various roles. Based largely on observational studies and a peer nomination method developed by Salmivalli and colleagues (1996), a growing literature suggests that there are at least four major participant roles in typical bullying episodes in addition to the perpetrator-target dyad. Two participant roles support the individual who bullies (the perpetrator in a particular incident). They are assistants, or henchmen, who get involved to help the perpetrator once the episode has begun, and reinforcers who encourage the perpetrator by laughing or showing other signs of approval. Supporting a target are defenders, who actively come to his or her aid. In observational research, less than 20 percent of witnessed bullying episodes had defenders who intervened on the target’s behalf, with defender actions successfully terminating the bullying about half the time (Hawkins et al., 2001). The presence of defenders in classrooms is associated with fewer instances of bullying behavior, whereas the presence of reinforcers is linked to increased incidence of bullying (Salmivalli et al., 2011).

The final participant role is bystanders, or onlookers, who are present during the bullying event but remain neutral (passive), helping neither the target nor the perpetrator. The low rate of observed defending indicates that bystanders coming to the aid of targets are relatively rare (Pepler et al., 2010). With increasing age from middle childhood to adolescence, bystanders become even more passive (Marsh et al., 2011; Pöyhönen et al., 2010; Trach et al., 2010). Passive bystander behavior reinforces the belief that targets of bullying are responsible for their plight and bring their problems on themselves (Gini et al., 2008). Bystanders doing nothing can also send a message that bullying is acceptable.

Given their potential to either counter or reinforce the acceptability of

bullying behavior, bystanders have been the focus of most participant role research; the goal has been to examine what factors might tip the scales in favor of their assisting the perpetrator or the target (i.e., becoming either reinforcers of the bullying or defenders of those bullied). Self-enhancement and self-protective motives likely encourage bystanders to support the perpetrator (Juvonen and Galván, 2008). Children not only improve their own status by aligning themselves with powerful perpetrators; they can also lower their risk of becoming the perpetrator’s next target.

Conversely, a number of personality and social status characteristics are associated with bystanders’ willingness to defend the target of a bullying incident. The degree of empathy for the child who is being bullied and the strength of bystanders’ sense of self-efficacy are predictors of the likelihood that witnesses become defenders (Gini et al., 2008; Pozzoli and Gini, 2010). Thus, it may not be enough to sympathize with the victim’s plight; going from passive bystander to active defender requires that witnesses believe they have the skills to make a difference. Witnesses who themselves have high social status and feel a sense of moral responsibility to intervene are also more likely to help the victim (Pöyhönen et al., 2010; Pozzoli and Gini, 2010).

By way of summary, a useful schematic representation of the various participant roles in a bullying incident was offered by Olweus (2001) in what he labels the Bullying Circle (see Figure 3-4). These roles are depicted as a continuum that varies along two dimensions: the attitude of different participants toward perpetrator and target (positive, negative, or indifferent) and tendency to act (that is, to get involved or not).

Research indicates that attitudes and intentions that define these roles vary depending on individual variables such as age, gender, personality, and social status, as well as contexts such as classroom norms favoring the perpetrator or the target. Whether bystanders defend or rebuff the perpetrator or target, as opposed to remaining passive, seems to be especially moderated by peer group norms. Bystanders are less likely to stand up for the target of a bullying event in classrooms where bullying has high prestige (i.e., where frequent perpetrators are the most popular children (Peets et al., 2015), but they are more likely to help when injunctive norms (the expectation of what peers should do) and descriptive norms (what they actually do) favor the target (Pozzoli et al., 2012). In some peer groups, bullying behavior will be tolerated and encouraged, while in other groups, bullying behavior will be actively dissuaded. For example, Sentse and colleagues (2007) found that 13 year olds who bullied others were rejected by peers if such behavior was not normative within their class. Conversely, in classes where bullying behavior was more common, or normative, frequent perpetrators were liked by their peers.

While social norms about bullying may be powerful, they are not al-

SOURCE: Adapted from Olweus (2001, Fig. 1.1, p. 15).

ways accurate. Studying perceived norms about bullying in middle school, Perkins and colleagues (2011) found that students overestimated the extent to which their peers engaged in bullying, were targets of bullying, and tolerated such behavior. An intervention that communicated accurate norms based on a schoolwide student survey indicating overwhelming disapproval of bullying resulted in less reported bullying over the course of a school year. When students were informed that their schoolmates did not approve of bullying, they were less likely to engage in the behavior themselves. This research illustrates the power of peer norms about the prevalence of and tolerance for bullying that can influence student participant roles, especially the willingness of bystanders to come to the aid of victims (Pozzoli et al., 2012).

Friends as Protective Factors

Friendships are very important for children’s development because they make it possible for children to acquire basic social skills. In the context of bullying, friendships represent a protective factor for children at risk of being bullied. Having friends, and particularly being liked by peers, is important in protecting against being targeted (Hodges et al., 1999; Pellegrini and Long, 2002). The number of friends seems to protect against being targeted; however, the protection is weaker when the friends are themselves targets of bullying incidents or have internalizing problems (Fox and Boulton, 2006; Hodges et al., 1999; Pellegrini et al., 1999). In a study to examine friendship quality as a possible moderator of risk factors in predicting peer bullying victimization, the findings of Bollmer and colleagues (2005) suggest that having a high-quality best friendship might function in different capacities to protect children from becoming targets of bullying and also to attenuate perpetration behavior.

FAMILY

The family context is perhaps one of the most influential on children’s development. As a result, it is not surprising that families also play a role in bullying prevention. However, the majority of research on family influences, from both a risk and resiliency perspective, has been on psychopathology and children’s adjustment (Collins et al., 2000), rather than on bullying specifically. These studies are further limited in that they are almost all cross-sectional correlational studies based on student self-report on the same instrument. Nevertheless, in this section the committee discusses some illustrative examples of how the family context can both exacerbate and attenuate the effect of individual characteristics on bullying outcomes.

Family functioning, typically assessed in terms of family involvement, expressiveness, conflict, organization, decision making to resolve problems, and confiding in each other (Cunningham et al., 2004), has been linked to perpetrator/target roles. For example, Stevens and colleagues (2002) found that Dutch children (ages 10-13) reported bullying others more when they also perceived their own family to be lower on family functioning. Rigby (1993) found that Australian girls, but not boys, were more likely to report being bullied if they also perceived their family to not be well functioning. Moreover, girls were more likely to report being bullied if they had a more negative relationship with their mother, whereas for boys, a negative relationship with an absent father predicted reports of being bullied (Rigby, 1993). Holt and colleagues (2008) examined the parent-child concordance of involvement with bullying and how family characteristics were related to bullying involvement. They found that American children (fifth grade) whose family life was characterized as less functional (i.e., higher levels of criticism, fewer rules, and more child maltreatment) were more likely to report being bullied. Involvement in bullying as a perpetrator was linked to poor supervision, child maltreatment, and greater exposure to intimate partner violence (Holt et al., 2008). In another moderator analysis of British adolescents ages 14-18, Flouri and Buchanan (2003) found that teens from single-parent families reported bullying others more than did teens from intact families. However, involvement in bullying was attenuated when the teens also reported that their mother and father were involved in their life—for example, by spending time with them, talking through their worries, taking an interest in school work, or helping with plans for the future (Flouri and Buchanan, 2003). Finally, Brittain (2010) found that fifth grade Canadian boys who reported being bullied but whose parents were unaware of their plight were less depressed if their parents reported higher family functioning. There are relatively few moderator analyses that address how family functioning affects prevalence of perpetrating behavior.

Whereas the findings from the above studies suggest that parental support can buffer youth against the negative effects of bullying behavior, other studies have shown that this effect is not consistent across all groups of youth. For example, using data from the Dane County Youth Assessment (DCYA), which included 15,923 youth in grades 7-12, Poteat and colleagues (2011) found that parental support was most consistent in moderating the effects of general and homophobic bullying behavior on risk of suicidality for heterosexual white and racial/ethnic minority youth who had been targeted in such incidents. However, in nearly all cases, parental support did not moderate these effects for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth, nor did it moderate the effects of these types of being bullied on the targets’ sense of school belonging. The authors speculate that one potential reason for these results is that LGBT students may

be less likely to discuss homophobic bullying with their parents than do heterosexual youth because of the stigma of homosexuality (e.g., discussing homophobic bullying could necessitate coming out to parents, which could lead to parental rejection and/or victimization). Another possibility raised by the authors is that general parental support, which was the focus of this study, is not sufficient to protect LGBT youth from the negative consequences of homophobic bullying behavior and that more specific forms of support (e.g., explicitly affirming an LGBT identity) might be required. Although more research is needed to understand the mechanisms underlying this result, this study demonstrates that the broader macrosystem context (e.g., stigma at the cultural level) renders some protective factors, such as parental support, less available to certain groups of youth. This research also highlights the importance of identifying contexts that are uniquely protective for specific subgroups of youth.

SCHOOLS

Bullying has been most studied within the school context, and several school-level factors have been identified as positive correlates of more prevalent bullying behavior. These factors include poor teacher-student relationships (Richard et al., 2012), lack of engagement in school activities (e.g., Barboza et al., 2009), and perceptions of negative school climates (Unnever and Cornell, 2004). In this section, the committee considers several factors at the school level that have been shown to moderate the effect of individual characteristics on bullying outcomes.

Organization of Instruction

School instructional practices can exacerbate the experience of bullying. In one recent study, Echols (2015) examined the role of academic teaming—the practice of grouping students together into smaller learning communities for instruction—in influencing middle school students’ bullying experiences. Students in these teams often share the majority of their academic classes together, limiting their exposure to the larger school community (Echols, 2015). The social and academic benefits of small learning communities have been highlighted in the literature (Mertens and Flowers, 2003). However, Echols (2015) found that, for students who were not well liked by their peers, teaming increased the experience of being bullied by their peers4 from the fall to spring of sixth grade. In other words, socially vulnerable adolescents who were traveling with the same classmates throughout most of the school day were found to have few opportunities to redefine their social identities or change their status among peers. Related to this work, research on classroom size has shown that smaller classrooms or learning communities (relative to large classrooms or learning environments) sometimes magnify the effects of being bullied on adjustment because the targets of bullying are more visible in these less populated settings (Klein and Cornell, 2010; Saarento et al., 2013).

Organization of Discipline

Fair discipline practices in schools can reduce the risks associated with bullying behavior as well as the amount of bullying that occurs. Disciplinary structure is the degree to which schools consistently and fairly enforce rules, while adult support is the degree to which teachers and other authority figures in schools are perceived as caring adults. Recent studies found that high schools with an authoritative discipline climate, characterized by high levels of both disciplinary structure and adult support for students, had fewer reported bullying incidents (Cornell et al., 2013; Gregory et al., 2010). In contrast, high schools with low structure and low support had the highest prevalence of bullying behavior. Rather than embracing zero tolerance policies that exclusively focus on structure (rule enforcement), more authoritative approaches to discipline view both structure and support as necessary and complementary. In a large study of several hundred high schools in Virginia that surveyed ninth graders and their teachers, Gregory and colleagues (2010) found that both students and teachers reported lower prevalence of bullying in schools that were rated by students as high on

___________________

4 Self-reported victimization was measured by asking students how often someone engaged in aggression toward them (e.g., hitting, kicking, calling bad names, etc.) since the beginning of the school year.

structure regarding fair rule enforcement and high on warm supportive relationships with adults. Moderation was not explicitly tested in this study, but it raises the possibility that the organization of school discipline can serve as a contextual modifier of individual characteristics on bullying behavior, which should be explored in future research.

Classroom Norms

A specific type of research on school norms relates to deviation from classroom and school norms. As has been found in other analyses of person-context mismatch (Stormshak et al., 1999; Wright et al., 1986), children who have been bullied might feel especially bad when this role pattern is discrepant with the behaviors of most other students in their classroom or school. When bullying is a rare occurrence in classrooms or schools, children and youth who are bullied exhibit higher levels of anxiety and depression compared to children and youth who are bullied in classrooms or schools with higher prevalence of bullying (Bellmore et al., 2004; Leadbeater et al., 2003; Schacter and Juvonen, 2015). Four studies on bullying and classroom or school norms that are consistent with this mismatch hypothesis are described in more detail below.

Leadbeater and colleagues (2003) reported that first graders with higher baseline levels of emotional problems, compared to children with low baseline levels of emotional problems, experienced more instances of being bullied when they were in classrooms with a high level of social competence among students. To the extent that first graders’ own ratings of bullying behavior and prosocial acts deviated from the classroom norm and they were high in perceiving themselves as targets of bullying, they were judged by their teachers to be depressed and sad (Leadbeater et al., 2003). Similarly, Bellmore and colleagues (2004) documented that the relation between being bullied and social anxiety was strongest when sixth grade students resided in classrooms that were judged by their teachers to be orderly rather than disorderly. In this case, the more orderly classrooms were those in which students on average scored low on teacher-rated aggression (Bellmore et al., 2004).

Most recently, Schacter and Juvonen (2015) examined victimization and characterological self-blame in the sixth grade of middle schools that were characterized as either high or low in overall prevalence of bullying behavior. Characterological self-blame refers to perceptions of self-blame that are internal, attributable to uncontrollable causes, and are stable. The authors found that characterological self-blame increased from the fall to spring for bullied students attending school with low (relative to high) overall prevalence of bullying, a result that suggests that a perception of deviating from the school norm increased students’ endorsement of attributions

for being bullied to factors that implicate one’s core self. In all four studies, a positive classroom or school norm (prosocial conduct, high social order, low peer victimization) resulted in worse outcomes for bullied children who deviated from those norms than in contexts where the classroom or school norm was less positive.

Ethnic Composition of Classrooms and Schools

Today’s multiethnic urban schools are products of the dramatic changes in the racial/ethnic composition of the school-age population in just a single generation (Orfield et al., 2012). For example, since 1970, the percentage of White non-Latino students in U.S. public schools has dropped from 80 percent to just over 50 percent, while Latinos have grown from 5 percent to 22.8 percent of the school-age (kindergarten through twelfth grade) population in U.S. public schools. As American public schools become more ethnically diverse, researchers have examined whether some ethnic groups are more vulnerable to peer bullying than others, in the context of varying levels of ethnic composition of classrooms and schools (Rubin et al., 2011). Rather than restricting analyses to comparisons between different racial/ethnic groups, these studies have examined whether students are in the numerical majority or minority in their school context. From this research, it is evident that bullied students are more likely to be members of numerical-minority ethnic groups than majority groups (see Graham, 2006; Graham and Bellmore, 2007). Such findings are consistent with theoretical analyses of bullying as involving an imbalance of power between perpetrator and target (Rubin et al., 2011). Numerical majority versus minority status is one form of asymmetric power relation.

As a further elaboration on the study of ethnic context, it has also been documented that members of the ethnic majority group who are bullied face their own unique challenges. For example, students with reputations as being bullied who are also members of the majority ethnic group feel especially anxious and lonely, in part because they deviate from what is perceived as normative for their numerically more powerful group (i.e., to be aggressive and dominant) (Graham et al., 2009). Deviation from the norm can then result in more self-blame (“it must be me”).

If there are risks associated with being a member of either the minority or majority ethnic group, then this has implications for the kinds of ethnic configurations that limit both the amount and impact of bullying. Research indicates that the best configuration is an ethnically diverse context where no one group holds the numerical balance of power (Felix and You, 2011; Juvonen et al., 2006). According to Juvonen and her colleagues (2006), using a sample of 2,000 sixth graders from 11 middle schools in southern California, greater ethnic diversity within a classroom was associated with

lower levels of self-reported experiences of being bullied. Similarly, using a sample of 161,838 ninth and eleventh grade students from 528 schools in California (drawn from the California Healthy Kids Survey’s 2004-2005 data sample), Felix and You (2011) found that school diversity was related to less physical and verbal harassment from peers.

In summary, a great deal of American bullying research is conducted in urban schools where multiple ethnic groups are represented, but much of that research is just beginning to examine the role that ethnicity plays in the experience of bullying behavior (Graham and Bellmore, 2007). There is not enough evidence that ethnic group per se is the critical variable, for there is no consistent evidence in the literature that any one ethnic group is more or less likely to be the target of bullying (see the meta-analysis by Vitoroulis and Vaillancourt, 2014). Rather, the more important context variable is whether ethnic groups are the numerical majority or minority in their school. Numerical-minority group members appear to be at greater risk for being targets of bullying because they have fewer same-ethnicity peers to help ward off potential perpetrators; youth who are bullied but members of the majority ethnic group may suffer more than numerical-minority youth who are bullied because they deviate from the norms of their group to be powerful, and ethnically diverse schools may reduce actual rates of bullying behavior because the numerical balance of power is shared among many groups. These studies serve as a useful starting point for a much fuller exploration of the ways in which school ethnic diversity can be a protective factor.

Teachers

Teachers and school staff are in a unique and influential position to promote healthy relationships and to intervene in bullying situations (Pepler, 2006). They can play a critical role in creating a climate of support and empathy both inside and outside of the classroom. Although teachers are not considered a direct part of the peer ecology, they are believed to have considerable influence on the peer ecology by directly or indirectly shaping students’ social behavior as well as by acting as bridging agents to other settings and other adults that influence the child’s development (Gest and Rodkin, 2011). They are the one group of professionals in a child’s life who have the opportunity to view the whole child in relation to the social ecology in which he or she is embedded (Farmer et al., 2011b).

Teachers vary in the behavior they identify as bullying, and they also perceive the various types of bullying differently (Blain-Arcaro et al., 2012). When teachers identify bullying situations, they are more likely to intervene if they perceive the incident to be serious, if they are highly empathic with the individual who is being bullied, or if they show high levels of self-

efficacy (Yoon, 2004). Several studies have shown that teachers perceive physical bullying as more serious than verbal bullying and verbal bullying as more serious than relational bullying. Accordingly, they are more likely to intervene on behalf of students whom they believe are being physically bullied and/or who show distress (Bauman and Del Rio, 2006; Blain-Arcaro et al., 2012; Craig et al., 2011). Both teachers and education support professionals have said that they want more training related to bullying and cyberbullying related to sexual orientation, gender, and race (Bradshaw et al., 2013).

Teachers are unlikely to intervene if they do not have proper training (Bauman et al., 2008). Both students and teachers report that teachers do not know how to intervene effectively, which prevents students from seeking help and contributes to teachers ignoring bullying (Bauman and Del Rio, 2006; Salmivalli et al., 2005). More than one-half of bullied children do not report being bullied to a teacher, making it that much more important that teachers be trained in varied ways of identifying and dealing with bullying situations. Teachers who participated in a bullying prevention program that included teacher training felt more confident about handing bullying problems, had more supportive attitudes about students who were targets of bullying, and felt more positive about working with parents regarding bullying problems (Alsaker, 2004).

Teachers’ beliefs, perceptions, attitudes, and thoughts affect how they normally interact with their students (Kochenderfer-Ladd and Pelletier, 2008; Oldenburg et al., 2015; Troop-Gordon and Ladd, 2015). Teachers who have been bullied in the past may have empathy for children who are bullied by their peers. For example, teachers who report having been bullied by peers in childhood tend to perceive bullying as a problem at their school (Bradshaw et al., 2007). Also, teachers who were more aggressive as children may be less empathetic toward targeted children and less inclined to address students’ aggressive behavior, compared with teachers who were less aggressive as children (Oldenburg et al., 2015).

Connectedness to others has been shown to be a significant buffer for developing adjustment problems among bullied youth. Specifically, studies indicate that having at least one trusted and supportive adult at school, which in many cases is a teacher, can help buffer LGBT youth who are bullied from displaying suicidal behaviors (Duong and Bradshaw, 2014). Related research on peer connections and school connectedness also indicates that youth who are more connected are less likely to be bullied, and even when they are bullied, they are less likely to develop a range of adjustment problems (e.g., internalizing problems) (Morin et al., 2015).

This research has been largely descriptive, examining correlates associated with teachers’ likelihood of intervening to address bullying. Consequently, understanding which contextual factors may be associated with

whether teachers are more or less likely to intervene to address bullying that targets some groups of youth (and not others) is an important avenue for future inquiry.

COMMUNITIES

Although most research on contextual moderators on bullying outcomes has focused on factors at the peer, family, and school levels, research has also begun to examine ways in which contextual factors at the community level serve as important modifiers. Generally, these factors have focused on neighborhood correlates, such as neighborhood safety (Espelage et al., 2000) and poverty (Bradshaw et al., 2009), but broader cultural factors, including exposure to violent television (Barboza et al., 2009), have also received some attention in the literature. In this section, the committee reviews three such modifiers of bullying outcomes at the community level—community norms, neighborhood context, and acculturation context.

Community Norms

Community norms are contextual factors that can differentially shape the experience of bullying. In one illustrative example, researchers demonstrated that body weight norms (e.g., acceptance of heavier bodies) differ across racial/ethnic groups. For example, in one laboratory-based study, Hebl and Heatherton (1998) had black and white women rate photographs of thin, average, and large black and white women. Whereas white women rated large women (especially large white women) lower on a variety of dimensions (e.g., attractiveness, intelligence, happiness, relationship and job success) than average or thin women, these patterns were not observed among black women, especially when they were rating large black women (Hebl and Heatherton, 1998). Consistent with this finding, one nationally representative study of over 20,000 overweight/obese participants found that blacks were less likely than whites to perceive discrimination based on weight (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2009).

How might these community norms around body image and weight affect weight-based bullying among youth? Most studies on this topic have been conducted among samples of exclusively white youth. However, some studies that have stratified their analyses by race/ethnicity have shown differences in weight-based teasing and stigmatization (weight-based bullying as a distinct outcome has not been examined). For instance, in data from Project EAT (Eating Among Teens), a longitudinal study of 1,708 adolescent boys and girls, overweight black girls were significantly less likely than overweight white girls to report ever being teased about their weight by their peers. Further, among those who were teased, fewer black girls than

white girls were bothered by peer teasing due to weight (Loth et al., 2008). This finding of moderation by race has been replicated in other studies with similar outcomes. For instance, in a study of 157 youth, ages 7-17, black girls reported significantly lower levels of weight-based stigmatization than white girls (Gray et al., 2011). Studies that explicitly model statistical interactions between race and community norms are needed to fully test this hypothesis, but the available evidence suggests that community norms can act as a contextual moderator of weight-based bullying.

Neighborhood Context

Neighborhood contexts may also serve as a contextual moderator of bullying outcomes. In one example of a study on neighborhood factors, researchers obtained data on LGBT hate crimes involving assaults or assaults with battery from the Boston Police Department; these crimes were then linked to individual-level data from a population-based sample of Boston high school students (n = 1,292). The results indicated that sexual-minority youth residing in neighborhoods with higher rates of LGBT assault hate crimes were significantly more likely to report being bullied, compared with sexual-minority youth residing in neighborhoods with lower rates of LGBT assault hate crimes (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2015b). No associations were found between overall neighborhood-level violent crimes and reports of being bullied among sexual-minority adolescents, which is evidence for the specificity of the results to LGBT assault hate crimes. Importantly, although moderation was not explicitly modeled in this study, no associations were found between LGBT assault hate crimes and reports of being bullied among heterosexual adolescents. This result suggests the effect of neighborhood climate on bullying outcomes was specific to the sexual minority adolescents.

Acculturation Context

Acculturation is defined as the “process of adapting to or incorporating values, behavior, and cultural artifacts from the predominant culture” (Sulkowski et al., 2014, p. 650). Berry (2006, p. 287) defined acculturative stress as stress reactions to “life events that are rooted in the experience of acculturation.” He found that acculturative stress can take a variety of forms, ranging from individual (e.g., coping with a socially devalued identity) and familial (e.g., navigating pressures that emerge from potential conflicts between disparate cultural groups) to structural (e.g., difficulties resulting from restrictive immigration policies). Although there is a large literature on acculturation and acculturative stress as predictors of mental health outcomes among adolescent immigrant populations in the United States (Gonzales et al., 2002), less is known about how acculturation and acculturative stress may influence bullying outcomes among this population (Smokowski et al., 2009). However, preliminary evidence suggests that acculturation and acculturative stress are associated with being a target of bullying for Latino and Asian/Pacific Islander adolescents in the United States (Forrest et al., 2013; Stella et al., 2003) and for immigrant youths in Spain (Messinger et al., 2012).

These studies have begun to suggest important insights into associations between acculturation, acculturative stress, and bullying, but there is currently a dearth of literature explicating the mechanisms through which these factors might be related to bullying outcomes. For instance, some research indicates that parent-adolescent conflict and low parental investment might partially explain the relationship between acculturation and youth violence outcomes, especially among Latino adolescents, but this work is still in its initial stages, and the identification of other mediators is warranted (Smokowski et al., 2009). Moreover, few of these studies have explicitly examined acculturation and acculturative stress as contextual modifiers of bullying behaviors among adolescents. Thus, the identification of mediators and moderators that influence the association between acculturation, acculturative stress, and related factors (e.g., ethnic identity) and bullying outcomes remains an important direction for future research.

MACROSYSTEM

As discussed at the beginning of this chapter, the broadest level of Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological model of development is the macrosystem, which includes societal norms, or “blueprints,” that may be expressed through ideology and/or laws. The macrosystem has received less attention when compared to other contextual factors (e.g., peers, parents, schools) in the bullying literature. However, there is emerging evidence that the macrosys-

tem is an important context that has implications for understanding the disproportionate rates of bullying among certain groups of youth, as well as the types of bullying (i.e., bias-based bullying) that some youth experience.

With respect to bullying, one important aspect of the macrosystem is the characteristics, identities, and/or statuses that a particular society devalues—that is, who and what is the target of stigma. Goffman (1963, p. 3) defined stigma as “an attribute that is deeply discrediting” and noted that there are three types of stigma: stigma related to physical attributes; stigma related to an individual’s character; and stigma related to an “undesired difference from what we had anticipated” (Goffman, 1963, p. 5). In one of the most widely used definitions of stigma, Link and Phelan (2001, p. 367) stated that stigma exists when the following interrelated components converge:

In the first component, people distinguish and label human differences. In the second, dominant cultural beliefs link labeled persons to undesirable characteristics—to negative stereotypes. In the third, labeled persons are placed in distinct categories so as to accomplish some degree of separation of “us” from “them.” In the fourth, labeled persons experience status loss and discrimination that lead to unequal outcomes. Stigmatization is entirely contingent on access to social, economic and political power that allows the identification of differentness, the construction of stereotypes, the separation of labeled persons into distinct categories and the full execution of disapproval, rejection, exclusion and discrimination. Thus we apply the term stigma when elements of labeling, stereotyping, separation, status loss and discrimination co-occur in a power situation that allows them to unfold.

At the macrosystem level, stigma is promulgated through laws and policies that differentially target certain groups for social exclusion or that create conditions that disadvantage some groups over others (Burris, 2006; Corrigan et al., 2004). Examples include constitutional amendments that banned same-sex marriage for gays and lesbians, differential sentencing for crack as opposed to powdered cocaine for racial minorities, immigration policies that allow special scrutiny of people suspected of being undocumented for Latinos, and a lack of parity in medical treatment of mental illness for people with mental disorders. Stigma is also expressed at the level of the macrosystem through broad social norms that create and perpetuate negative stereotypes against certain groups (Herek and McLemore, 2013). There is emerging evidence that stigma at the macrosystem level contributes to adverse health outcomes among members of stigmatized groups and explains health disparities that exist between stigmatized and non-stigmatized populations (for reviews, see Hatzenbuehler, 2014; Link and Hatzenbuehler, 2016; Richman and Hatzenbuehler, 2014). Thus, stigma

is manifested in the macrosystem through laws, policies, and social norms that in turn serve as a significant source of stress and disadvantage for members of stigmatized groups.

The role of stigma in bullying is evident in the groups of youth that are expressly targeted for bullying. As reviewed in Chapter 2, several groups of youth—including LGBT youth (Berlan et al., 2010), youth with disabilities (Rose et al., 2009), and overweight/obese youth (Janssen et al., 2004)—are at increased risk of being bullied, and each of these characteristics or identities (sexual orientation, disability status, obesity) is stigmatized within the current U.S. context, as is evident in laws and policies, institutional practices, and broad social/cultural attitudes surrounding these characteristics or identities (Herek and McLemore, 2013; Puhl and Latner, 2007; Susman, 1994).

Evidence for the role of stigma in bullying is also found in the particular types of bullying that some youth face—namely, bias-based bullying. Greene (2006) defined bias-based bullying as “attacks motivated by a victim’s actual or perceived membership in a legally protected class” (p. 69) and distinguished this form of bullying from general (i.e., nonbias-based) bullying, which is motivated by student characteristics unrelated to group membership, such as personality (Greene, 2006). According to this definition, a student does not have to identify with a particular identity (e.g., gay) or be a member of a social group (e.g., Muslim) to be the target of bias-based bullying; if bullying occurs because the perpetrator merely perceives that the target is a member of a legally protected class, it is enough to warrant the label of bias-based bullying.

While early research on bullying largely neglected to consider youths’ motivations for bullying behaviors, recent research has documented that some bullying and related forms of peer victimization, such as harassment, are due to bias and discrimination. In one example of this work, Russell and colleagues (2012) used data from two population-based surveys of adolescents: the 2008-2009 Dane County Youth Assessment (DCYA; n = 17,366) and the 2007-2008 California Healthy Kids Survey (CHKS; n = 602,612). In the DCYA, adolescents were asked how often they had been “bullied, threatened, or harassed” in the past 12 months because they were perceived as lesbian, gay, or bisexual or because of their race/ethnicity. In the CHKS, adolescents were asked about bias-based bullying/harassment due to sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, religion, gender, and physical or mental disability in the past 12 months. Respondents were also asked about general forms of bullying and harassment not due to any of these specific categories. Among adolescents who reported being bullied or harassed, over one-third (DCYA: 35.5%, CHKS: 40.3%) reported bias-based bullying/harassment, underscoring how prevalent this basis for bullying is among adolescents.

Researchers have also examined relationships between bias-based bul-

lying/harassment and several adverse outcomes, including substance use, mental health, and school-related outcomes (e.g., grades, truancy), and recent evidence suggests that experiences of bias-based bullying may be related to more negative outcomes than general forms of bullying. For instance, in the aforementioned study by Russell and colleagues (2012), mental health status and substance use outcomes were worse among youth who experienced bias-based bullying/harassment than among those who experienced bullying/harassment that was unrelated to bias. Similar results were observed in a convenience sample of 251 ninth-to-eleventh grade students in an all-male college preparatory school; boys who reported bias-based bullying due to perceived sexual orientation (“because they say I’m gay”) experienced more adverse outcomes (e.g., symptoms of anxiety and depression, negative perceptions of school climate) than boys who reported being bullied for reasons unrelated to perceived sexual orientation (Swearer et al., 2008). These findings are consistent with evidence that hate-crime victimization among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults is associated with greater psychological distress than is crime victimization that is unrelated to bias (Herek et al., 1999).

Taken together, this research highlights the role of stigma and related constructs (bias, discrimination) in explaining disparities in responses to being bullied and in revealing motivations for some forms of bullying. However, the role of stigma and its deleterious consequences is more often discussed in research on discrimination than on bullying. In the committee’s view, there needs to be more cross-fertilization between these two literatures. Moreover, this research suggests that interventions need to target stigma processes in order to address disparities in bullying and reduce bias-based bullying. However, as is evident in Chapter 5 (Preventive Interventions), bullying prevention programs currently do not incorporate theories or measures of stigma and therefore overlook one important mechanism underlying motivations for bullying. Thus, new intervention models are necessary to address the under-recognized role of stigma in bullying behaviors.

AREAS OF FUTURE RESEARCH

This chapter reviewed studies that examined social contexts that either reduce or exacerbate the influence of individual characteristics (e.g., weight status, sexual orientation, and race/ethnicity) on bullying outcomes. This approach explicitly required analyses of moderation in addition to analyses of contextual correlates. However, other studies have identified contextual correlates that may also serve as moderators but have thus far not been examined as such. In this section, the committee reviews contextual correlates

at the school and community level that warrant greater attention in future studies that are explicitly attentive to moderation.

School Climate

There is a lack of consensus in the research literature on the definition of “school climate” and the parameters with which to measure it. Consequently, the term “school climate” has been used to encompass many different aspects of the school environment (Thapa et al., 2013; Zullig et al., 2011). For instance, perceptions of school climate have been linked to academic achievement (Brand et al., 2008); school attendance and school avoidance (Brand et al., 2003); depression (Loukas et al., 2006); and various behavior problems or indicators of such problems, including bullying (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2009), and school suspensions (Bear et al., 2011). Examining the possible link between school climate and bullying is an important component of the bullying literature, since demonstrating this link establishes bullying as a systemic problem that needs to be understood at the macro level, not just as a result of microlevel factors (Swearer and Espelage, 2004).

The available literature indicates that negative school climate is associated with greater aggression and victimization; additionally, positive school environment is associated with fewer aggressive and externalizing behaviors (Espelage et al., 2014; Goldweber et al., 2013; Johnson, 2009). Several studies have found a direct relation between school climate and the psychological adaptation of the individual (Kuperminc et al., 2001; Reis et al., 2007). It has been found, for example, that children attending a school in which behaviors such as bullying were acceptable by the adults were at greater risk of becoming involved in such behaviors (Swearer and Espelage, 2004). Schools that have less positive school climates may exhibit lower quality interactions between students, teachers, peers, and staff (Lee and Song, 2012).

Available literature on authoritative climate, a theory that posits that disciplinary structure and adult support of students are the two key dimensions of school climate (Gregory and Cornell, 2009), provides a conceptual framework for school climate that helps to specify and measure the features of a positive school climate (Cornell and Huang, 2016; Cornell et al., 2013; Gregory et al., 2010). Disciplinary structure refers to the idea that school rules are perceived as strict but fairly enforced. Adult support refers to student perceptions that their teachers and other school staff members treat them with respect and want them to be successful (Konold et al., 2014). A study to examine how authoritative school climate theory provides a framework for conceptualizing these two key features found that higher disciplinary structure and student support were associated with lower prevalence of

teasing and bullying and of victimization in general. An authoritative school climate is conducive to lower peer victimization (Cornell et. al., 2015). Overall, schools with an authoritative school climate are associated with positive student outcomes (Cornell and Huang, 2016) and lower dropout rates (Cornell et al., 2013; Jia et. al., 2015).

School Transition

As children progress through the education system they often change schools. For some, the transition to a new school is positive, while for others the transition is linked to difficulties related to academic functioning, school connectedness and engagement, and self-esteem (Forrest et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2015; Wigfield et al., 1991). A number of factors may be associated with negative perceptions of school transition (Wang et al., 2015). These factors include students’ social functioning (McDougall and Hymel, 1998), school environment (Barber and Olsen, 2004), mental health (Benner and Graham, 2009), students’ academic attitudes and perceptions of academic control and importance (Benner, 2011), family characteristics (Barber and Olsen, 2004), and pubertal development (Forrest et al., 2013).

School transition has been associated with students’ involvement in bullying. Most early work suggested that bullying perpetration was more common among children after the transition to a new school as part of the normal school transition process. (Pellegrini and Bartini, 2000; Pellegrini and Long, 2002; Pepler et al., 2006), and this increase in bullying perpetration was presumed to be driven by the changes in the peer group. That is, with a new change to the social landscape, children were presumed to bully others as a way of gaining social status within their new social environment. One issue with these studies, however, is that they had no comparison group: the group of transitioning students was not compared with a group of students who did not change schools. Thus, one cannot determine whether the reported differences in bullying rates were due to a change associated with typical development or if they resulted from a change in the social context.

In two more recent moderation studies, this well-accepted finding is challenged. Specifically, Farmer and colleagues (2011a) and Wang and colleagues (2015) found that students in schools without a transition reported higher rates of being bullied and bullying perpetration than did students in schools with a transition. These findings support a conclusion that context matters in understanding changes in patterns of bullying behavior over the school transition years.

Gay-Straight Alliances

Gay-Straight Alliances (GSAs) are typically student-led, school-based clubs existing in middle and high schools with goals involving improving school climate for LGBT youth and educating the school community about LGBT issues. GSAs typically serve four main roles: as a source of counseling and support for LGBT students; as a safe space for LGBT students and their friends; as a primary vehicle for education and awareness in schools; and as part of broader efforts to educate and raise awareness in schools (Greytak and Kosciw, 2014). Although studies have established GSAs as correlates of lower rates of victimization among LGBT youth (Goodenow et al., 2006), only one study of 15,965 students in 45 Wisconsin schools has examined interactions between GSAs and sexual orientation in predicting general or homophobic victimization (Poteat et al., 2013).5 Although no statistically significant interaction was found between GSAs and sexual orientation in predicting these outcomes, there was a trend (i.e., lower levels of general and homophobic victimization among LGBT youth in schools with GSAs). Thus, future research is needed to examine whether school diversity clubs do moderate the impact of individual characteristics on bullying outcomes.

Extracurricular Activities and Out of School-time Programs

Eighty percent of American youth ages 6-17 participate in extracurricular activities, which include sports and clubs (Riese et al., 2015). Although most children and youth participate in out-of-school activities, most researchers have only examined bullying within the school context. Only a few studies have examined bullying outside of school, and their results have been mixed. For example, in one study examining the risk behavior of high school athletes, results indicated that 41 percent had engaged in bullying perpetration (Johnson and McRee, 2015). This result is consistent with other studies showing that the social elite of a school, which tends to be dominated by athletes, engage in a disproportionate amount of bullying perpetration (Vaillancourt et al., 2003). It is also consistent with studies showing an association between participation in contact school sports like football and the perpetration of violence (Kreager, 2007). However, a recent study using data from the National Survey of Children’s Health (ages 6-17), suggests that involvement in extracurricular activities, which includes sports, is associated with less involvement in bullying perpetration (Riese et al., 2015).

The protective role of sports on children’s well-being is well docu-

___________________

5 Homophobic victimization was measured using the following item: “In the past twelve months, how often have you been bullied, threatened, or harassed about being perceived as gay, lesbian, or bisexual?” (Poteat et al., 2013, p. 4).

mented (Guest and McRee, 2009; Vella et al., 2015), although somewhat mixed depending on the outcome used by the study (see review by Farb and Matjasko, 2012). For example, Taylor and colleagues (2012) reported that among African American girls, participation in sports was associated with lower rates of bullying behavior and that this relation was mediated by self-esteem, which was also enhanced in sport-participating girls. However, in another study examining involvement with school sports and school-related extracurricular activities in a nationally representative sample of 7,990 American students from 578 public schools, results indicated that involvement in intramural sports and classroom-related extracurricular activities increased the likelihood of being bullied by peers, while participation in interscholastic sports was associated with a decreased likelihood of being a target of bullying (Peguero, 2008).

Virtual and Media Contexts

Outside of school, the online world is among the most common public “places” where today’s adolescents spend time. Social media platforms, such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram are used by the majority of youth; most youth log into social media at least once daily, and most youth maintain more than one social media platform (Lenhart et al., 2015). Social media provides youth opportunities to stay connected to friends, develop an online identify, and seek information about peers. Studies have shown that peer interactions online can be just as important, in relation to self-esteem and friendships, as those expressed offline (Valkenburg and Peter, 2011). Other work has illustrated that social media has become a normative part of the friendship formation and maintenance process (Chou and Edge, 2012). Because of the popularity of these tools among youth, and their easy, anytime-access using mobile devices, they have become woven into the fabric of teens’ lives and relationships. These technologies present both new opportunities and challenges to teens as they navigate relationships, social situations, and bullying behavior.

There is evidence to support a correlation between being bullied online and in person (Ybarra and Mitchell, 2004). Few studies have explored different online contexts as moderators of the bullying experience, but some factors that are present in the online world have been proposed to explain how the online context may moderate the experience of bullying. In contrast to school-based bullying, where a youth can seek respite at home, the online context is available 24/7 and may lead to a youth feeling that the bullying experience is inescapable (Agatston et al., 2007). A second factor is that in contrast to in-person bullying where the perpetrator’s identity is easily known, the online context provides the potential for bullying to be anonymous. However, a recent study found that cases in which a perpetra-

tor’s identity is unknown to a target are relatively infrequent (Turner et al., 2015). A third factor differentiating the online context is that a single bullying event can be distributed widely (or “go viral”), which can lead to varied interpretations of what it means to have a bullying experience be repeated (Turner et al., 2015).

An area in which concern for bullying experiences exists but little research has been done is in the online gaming context. Studies have shown that video game play is nearly universal among youth, and approximately a third of males reported playing games every day (Olson et al., 2007). A salient feature of the online video game environment that may impact bullying rates or experiences are that many popular games promote aggressive behavior or violence to win the game; one study found that at least one-half of adolescents’ listed favorite games were violent in nature (Olson et al., 2007). A recent study found positive associations between the time spent using online games, exposure to violent media, and cyberbullying experiences, suggesting that spending time in online or media contexts that promote aggression or violence may be associated with bullying experiences (Chang et al., 2015).

Policy Context

Although research on anti-bullying policies has explored main effects (see Chapter 6), it is also possible for the policy context to serve as a moderator of bullying outcomes. For instance, literature related to both homophobia and bullying (Chesir-Teran, 2003; Rutter and Leech, 2006) suggests that teachers often fail to intervene for a variety of reasons, such as a limited knowledge of how to intervene and homophobic attitudes. This research, however, has largely focused on individual attitudes of teachers. A contextual factor that affects the likelihood of effective teacher intervention in instances of homophobic bullying is broader social policies that place unique burdens on teachers, including “No Promo Homo” laws. These state laws have different scope and reach, and in some cases only apply to some grades or certain domains of instruction. However, these laws can be vaguely written and misapplied and, in extreme cases, can expressly forbid teachers from discussing LGBT issues in a positive light. Such policies are currently in place in eight states: Alabama, Arizona, Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Texas, and Utah (Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network, 2015; Movement Advancement Project, 2015). They represent one example of a policy context moderating the extent to which individual actors (i.e., teachers) can effectively respond to bullying behavior.

SUMMARY

In this chapter, the committee moved beyond descriptive data to consider social contexts that moderate the effect of individual characteristics on bullying behavior. The chapter drew upon two theoretical and conceptual frameworks, the ecological theory of development and the concepts of equifinality and multifinality, to inform its approach to this chapter. Evidence from the four social contexts, including peers, family, schools, and communities, was reviewed, with a specific focus on studies that examine moderation (for a visual representation of these contexts as conceptualized by the committee, see Figure 3-5). With regard to peers, the group context is important to consider, given what is known about factors associated with bullying. As noted earlier in this chapter, some peer groups will tolerate and encourage bullying behavior, whereas in other groups, bullying behavior will be actively discouraged. Having friends and being liked by peers can protect children against being bullied, and having a high-quality best friendship might function in different capacities to protect children from being targets of bullying behavior.

Families can play an important role in bullying prevention, and family functioning has been linked to whether a child is identified as one who engages in bullying perpetration or one who is the target of bullying behavior. Whereas parent support can buffer some children and youth against the negative effects of bullying, this is not true across all groups of youth.

Bullying behavior has most often been studied in the school context. The organization of instruction, organization of discipline, classroom norms, the ethnic composition of classrooms and schools, and teachers are several factors at the school level that have been shown to moderate the effect of individual characteristics on bullying outcomes. A school’s instructional practices such as academic teaming can worsen the experience of bullying. Moreover, schools’ discipline climate is associated with individuals’ risk of being bullied as well as the amount of bullying that occurs. Further, positive classroom or social norms resulted in worse outcomes for children who were bullied and who deviated from those norms than for children with similar social experience but in contexts where the classroom or school norm was less positive.

With regard to the ethnic composition of schools, there is not sufficient evidence to indicate that ethnic group per se is the critical variable, as there is no consistent evidence that any one ethnic group is more or less likely to be the target of bullying. Numerical-minority group members appear to be at greater risk for being bullied because they have fewer same-ethnicity peers to help ward off potential perpetrators. Finally, teachers and school staff are in a position to promote healthy relationships and to intervene in

bullying situations in schools. They can also create a climate of support and empathy.

Three modifiers of bullying outcomes at the community level—community norms, neighborhood context, and acculturation context—were reviewed in this chapter. Community norms can differentially shape the experience of bullying. Similarly, neighborhood contexts may also serve as contextual moderators of bullying outcomes. There is also evidence that acculturative stress and acculturation are associated with being a target of bullying for Latino and Asian/Pacific Islander adolescents in the United States. Finally, the committee identified several contextual correlates at the school and community level that need greater attention in future studies that explicitly attend to moderation. These include school climate, school transition, school diversity clubs, extracurricular activities and out-of-school time programs, virtual and media contexts, and the policy context.

FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS

Findings

Finding 3.1: Research on bullying is largely descriptive (i.e., focused on prevalence rates or correlates of bullying, rather than on identifying mediators and moderators), which generally fails to fully address contextual factors that render individual characteristics more or less likely to be related to bullying experiences.

Finding 3.2: The ecological model provides a framework from which to further understand the influence that social contexts may have on both rates of being bullied and experiences of negative mental health outcomes among those who are bullied.

Finding 3.3: Bullying is conceptualized as a group phenomenon, with multiple peers taking on roles other than perpetrator and target. Peers are a critical social context that affects many aspects of bullying—in large part because peers influence group norms, attitudes, and behavior.

Finding 3.4: The seemingly low rate of observed defending indicates that bystanders coming to the aid of targets of bullying are relatively rare. Bystanders become even more passive with age.

Finding 3.5: Research indicates that attitudes and intentions that define roles in bullying situations vary depending on individual variables such as age, gender, personality, and social status, as well as contexts such as classroom norms favoring the perpetrator or target.

Finding 3.6: The majority of research on family influences, both from risk and resiliency perspectives, has been on psychopathology and children’s adjustment rather than on bullying specifically.

Finding 3.7: Teachers and school staff are in a unique and influential position to address bullying situations.

Finding 3.8: There is not enough consistent evidence that shows that one racial or ethnic group is more or less likely to be the target of bullying; rather, the more important contextual variable is whether racial or ethnic groups are the numerical majority or minority in their school.

Finding 3.9: Connectedness to others has been shown to be a significant buffer for the development of adjustment problems among bullied youth.

Finding 3.10: Contextual factors at the community level, such as community norms, neighborhood context, and acculturation context, serve as important moderators of bullying outcomes.

Finding 3.11: Contextual factors at the level of the macrosystem, such as stigma, contribute to bullying behaviors. In particular, several stigmatized groups of youth (e.g., lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth; youth with disabilities) are at heightened risk for being targets of bullying. Moreover, stigma is one mechanism underlying some motivations to bully, as in the case of bias-based bullying. Recent research has suggested that youth who are targets of bias-based bullying/harassment report more adverse psychosocial outcomes compared to youth who are targets of bullying/harassment that is unrelated to bias.