2

Health System Transformation to Support Integration

The workshop opened with a presentation by Dennis Andrulis, senior research scientist at the Texas Health Institute and associate professor at the University of Texas School of Public Health, on the opportunities created by the ACA and other incentives for system transformation that support integration of health literacy, cultural competence, and language access services. This presentation was followed by a panel discussion to address two questions:

- What are the key concepts in this area?

- What three things have changed over time that facilitate integration?

The three panelists were Michael Wolf, professor of medicine and learning sciences and associate division chief of internal medicine and geriatrics, and director of the Health Literacy and Learning Program at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine; Guadalupe Pacheco, founder, president, and chief executive officer of the Pacheco Consulting Group; and Wilma Alvarado-Little, principal and founder of Alvarado-Little Consulting. Each panelist made a short presentation, which was then followed by an open discussion among the panelists and the workshop participants moderated by Bernard Rosof.

HOW THE AFFORDABLE CARE ACT AND OTHER INCENTIVES MAY SUPPORT INTEGRATION1

As a prelude to his presentation, Dennis Andrulis recounted growing up in a three-language family of immigrants that faced numerous challenges associated with literacy, language, and culture. He called the richness of that background a gift and a reason to appreciate the importance of this workshop. He then listed some of the emerging issues that make today’s efforts to integrate language, literacy, and culture different than in past times, starting with new financing and program initiatives, the new pressures and requirements around health contracts and insurance, and the reality of heightened competition. Andrulis said two important changes to the health care environment are contraction in the field through health system mergers and the simultaneous growth in the pool of insured Americans with increasing diversity of that pool. The new focus on population health and the social determinants of health create both opportunities and challenges, as does the increasing emphasis on community health needs. These and other factors create the greater complexity that Rosof noted in his introductory remarks, but they also set the context for opportunities that health care systems are starting to capitalize on as they transform themselves to succeed in the rapidly evolving U.S. health care environment.

Various provisions of the ACA are driving integration of language, literacy, and culture, Andrulis said, including

- Positive incentives, such as payments tied to implementation of the national standard for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) and health literacy;

- Penalties, or negative incentives, tied to readmissions, hospital-acquired conditions, and other aspects of ineffective care;

- New requirements, such as community health needs assessments, CLAS, and nondiscrimination in marketplace activities;

- Support through grants and contracts, including research grants from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI); and

- Symbolic support though unfunded initiatives that, with their very inclusion or explicit mention in the law, have symbolically elevated their priority and may have prompted related state focus or initiatives, such as the development of model cultural competence curricula.

___________________

1 This section is based on the presentation by Dennis Andrulis, senior research scientist at the Texas Health Institute, and associate professor at the University of Texas School of Public Health, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

With regard to the ACA’s health insurance provisions, Andrulis said that while much of the focus is on patient care and service systems, he has seen some interesting examples on the insurance marketplaces that are “thought provoking and have lessons for broader issues around literacy, language, and culture.” The ACA’s plain language requirements for benefit summaries, explanations of coverage, and claims appeals and the associated reporting requirements have triggered needed improvements, he noted, as have the navigator programs that require those working in those positions to have a language facility as well as literacy and culture training. Andrulis noted that he and his colleagues have studied some of the best training systems for enrollers and assisters and are in the process of documenting those efforts.

For health care systems, medical home and health home initiatives have provided states with incentives to develop evidence-based programs for communicating in a culturally and language-appropriate manner as part of their efforts to better coordinate care for Medicaid beneficiaries with chronic physical or mental illnesses. Iowa, New York, Ohio, and Oregon, for example, all require medical and health home providers to meet standards for communicating in health literate ways that meet the cultural and linguistic needs of the individual and family. Ohio is monitoring cultural competence using the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) National Outcome Measures. Several states also implemented programs to use evidence-based, culturally sensitive wellness and prevention programs with their Medicaid populations. Andrulis emphasized the importance of finding a point of focus for bringing health literacy, cultural competence, and language access services together in a synergistic manner. Otherwise, he said, efforts become fractured and fail to address all of the needs of patients. He also noted the opportunity to incentivize accountable care organizations to integrate health literacy, cultural competence, and access to language services by tying payments to measures of how well they communicate and the quality of the health education they provide to their patients.

Andrulis explained that the ACA’s training requirements have a rich potential to build cultural and linguistic competencies in the health care workforce. When he and his colleagues examined the ACA, they found 62 provisions related to disparities, equity, race, ethnicity, language, culture, and literacy, including opportunities to facilitate integration of these concepts in primary care training and loan repayment programs, team-based care, and support for community health workers who deal with populations with low health literacy. However, the intent of these provisions have yet to be fulfilled, largely because of a lack of funding to support such programs.

With regard to data and research, standards for collecting race, ethnicity, and language data are embedded in the ACA and represent a critical

step to uniformly collecting data to track, assess, and monitor progress in ending disparities. This is especially important, said Andrulis, given that health data, including patients’ race and ethnicity, are generally not collected in a uniform way (Weissman and Hasnain-Wynia, 2011). However, the implementation of this provision, particularly to authorize public programs, entities, and surveys to collect data using the standards, depend on appropriations, and the ACA states explicitly that without funding directly appropriated for this purpose, “data may not be collected under this section.” Nonetheless, this provision and the progress made to date have value and relevance for private payers and sectors, including health plans, hospitals, and other health care providers, said Andrulis. In particular, the passage of the meaningful use provision in the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act requires physicians to record race and ethnicity for at least half of their patients to receive incentives to implement electronic health records (EHRs). He noted that ACA Section 4302 provided helpful implementation guidance on ways to effectively and cohesively collect these data.

PCORI offers opportunities for integration through its focus on disparities research, said Andrulis, and particularly through interventions addressing patient characteristics, strategies for overcoming cultural and linguistic barriers, and health communication models to improve outcomes among patients with low literacy and numeracy. So, too, does the federal government’s focus on health equity in public health and prevention efforts that includes elevating the visibility and role of the Office of Minority Health at the policy level. One of the focus areas of the National Prevention Strategy is the elimination of health disparities, and toward this end, it has authorized a study of health literacy factors in patient safety; increased the use and sharing of evidence-based health literacy practices and interventions; mandated plain language patient information and labeling tailored to culture, language, and literacy; and required race, ethnicity; and language data collection.

Looking back 10 years, there were pieces of these programs and ideas floating around, said Andrulis, but today, efforts to integrate health literacy, cultural competence, and language access skills in all aspects of health care are more energized, supported, and seen as being more relevant. Looking ahead, it is important to frame integration of health literacy, cultural competence, and language access services in the context of today’s health system priorities. Population health, for example, is now accepted as an area of focus for health systems, and addressing literacy, culture, and language issues is recognized as a critical feature of any successful population health program. Andrulis noted, though, that while many organizations are moving into population health, policies regarding reimbursement of population health programs aimed at tackling the social determinants of health from

a prevention, community-based perspective are lagging. He recounted a conversation he had with a leader of a foundation in California who said that what physicians and health plan officials focus on is not prevention but areas that generate revenues. “We’ve been trying to push health systems toward population health, but where is the money coming from?” asked Andrulis.

It should also be easy to tie integration to value-based care and patient safety, said Andrulis. He noted that rates of readmission and other aspects of patient safety are related to literacy, language, and culture. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) is undertaking a demonstration at 10 hospitals as part of its Re-Engineered Discharge program to develop a tool to provide hospitals with guidance on providing education materials on diagnosis, home care, follow-up appointments, and medication adherence that are tailored to the patient’s culture and language. An English version of this program, said Andrulis, reduced readmissions by 30 percent. He repeated his earlier comments that it is important to draw on the lessons learned from the experiences of health insurance marketplaces in reaching and enrolling diverse populations (Jahnke et al., 2015).

Transformation-directed waiver programs at the state level also present opportunities for taking different approaches to integrate literacy, language, and culture. Texas and California, for example, pay for performance based on Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) scores on patient perceptions of physician communication and health literacy skills and cultural competence. Texas also pays for performance based on engagement of community health workers in evidence-based programs to increase the health literacy of targeted populations and on the success of navigators in programs aimed at populations with low English proficiency, immigrants, and populations with low health literacy. In addition, Texas is expanding language access and implementation of CLAS standards—including some over and above those required by federal regulation—through workforce cultural competence trainings, while California is paying health systems to redesign patient education materials to be at the appropriate reading level, as well as paying for translations of those materials.

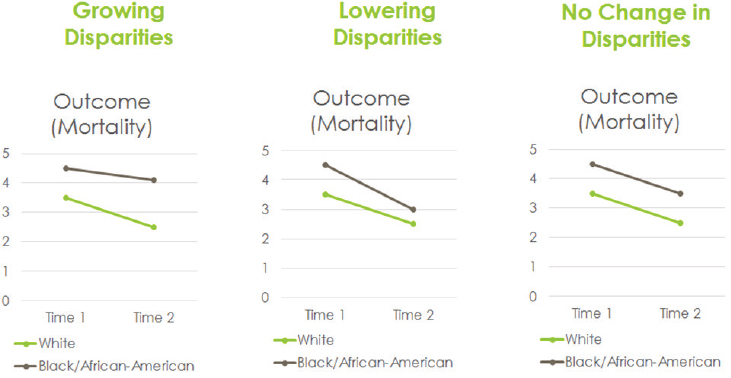

Going forward, said Andrulis, it is critical to build an evidence base both on the gaps in integrating health literacy, cultural competence, and language access services and on the beneficial effects on health that are realized when health systems address those gaps. This evidence base is essential for tying integration to payments and incentives. Also needed are programs to monitor health equity outcomes to ensure inequities are not an adverse outcome of related initiatives, which he explained using three hypothetical scenarios, one a desired scenario and the other two to be avoided (see Figure 2-1). In one undesirable scenario, individuals from advantaged and

SOURCE: Presented by Andrulis, October 19, 2015.

disadvantaged populations both benefit, but the already advantaged group benefits more and disparities increase. In a slightly less undesirable scenario, the effect of a program is equal to both groups, so there is no change in disparities. The desired scenario has individuals in both groups benefitting, but those in the disadvantaged group benefit more, reducing disparities. “I think without attention to literacy, language, and culture, you will have one or the other undesirable scenarios and you will not have the desired scenario,” said Andrulis.

In closing, Andrulis said that addressing shortcomings in literacy, language, and cultural competence is a necessary component for any system-level advance in terms of equity, quality, and value; without integration, progress will be limited. That lesson, he said, has been stated in earlier workshops held by the roundtable, and it continues to be true.

CONCEPTS IN HEALTH LITERACY2

What health literacy, cultural competence, and language access services have in common, said Michael Wolf, is stagnation and the challenge to have

___________________

2 This section is based on the presentation by Michael Wolf, professor of medicine and learning sciences, associate division chief of internal medicine and geriatrics, and director of the Health Literacy and Learning Program at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

anyone pay attention to them. He also proposed that Russian dolls could serve as an appropriate analogy for thinking about these three topics in that they would be the innermost dolls—one could argue about the order of the three—nesting inside larger dolls that represent health care quality, safety, and equity. “We have been struggling for a while now to have our message heard that all of these issues really do matter to quality. What we need is a good business case,” said Wolf. “That is still something of a black box in that it is still unclear how we make that case.”

Health literacy, in Wolf’s opinion, is both a risk factor and an outcome, something the IOM recognized in its first report on the subject in 2004 (IOM, 2004). He acknowledged that health literacy has perhaps taken too much of a medical focus in that it identifies as a risk factor a group that is vulnerable to poorer health outcomes. However, health literacy is also an outcome, something to promote, and that, said Wolf, is why health literacy has two faces, both as an individual and societal trait. Health literacy is not just an individual skill set, an accumulation of knowledge or prior experience. It is also a reflection of how knowledge is presented by the health literate health care organization and how those organizations are increasing access to the services it provides to those it serves.

Health literacy is also context dependent and modifiable. “In many ways, we have framed health literacy in the context of health care equity and health disparities, which makes it conducive to integration with cultural competency and language access,” said Wolf. “It feels less formidable as a task to say that we can do better at communicating information, letting people understand what their options may be, and informing them about health care decisions than to think of health literacy in terms of socioeconomic factors that cause disparity.” At its core, though, health literacy is an emphasis on accessing, understanding, and applying information to make informed health decisions and, at its best, facilitating health behavior change. Health literacy has strong and obvious ties to socioeconomic status, race, ethnicity, and age that, according to Wolf, cannot be divorced from making changes in the health system and beyond.

He then made three points with regard to how to best integrate health literacy, cultural competence, and language access services. The first was that health systems must expect and prepare for diversity in the way they communicate about health care, train providers, and organize workflow. The Plain Writing Act of 2010 and the changes in health coverage triggered by the ACA are now forcing health systems to consider how they interface with patients. However, said Wolf, the health literacy community knew what needed to be done long before those mandates and has done a poor job of disseminating what it has learned. In the end, what is needed is for health literacy principles to be hardwired into the practice of health care. But the question that arises is whether the investment to do so is justifiable.

He noted that in the absence of a good business case, even wealthy health care systems such as the one he works for, will wonder if they should invest in health literate communications, provider training, workflow redesign, and developing a quality indicator to show how well they are communicating with patients.

The second point he made about integration was that all three of these topics reflect the needs of vulnerable populations with known disparities. They therefore warrant ongoing assessment to show that efforts to address these topics are reducing disparities and closing the gap between those with the lowest literacy skills and the rest of the population. The question then becomes how to measure health literacy, cultural competence, and access to language services. Wolf said that CAHPS can provide some information. He wondered, too, if EHRs either contain or could be used to collect relevant data on health literacy. He noted that while the health care system likes to think of itself as progressive, in some ways it is not because it still demands there be a business case for taking action.

Wolf’s final point was that interventions must target improving access to understandable, actionable health information for everyone. The bottom line is that health literacy is a patient-centered approach to health information applicable to a diverse audience. From that perspective, cultural competence principles and access to language services become natural components of any effort to improve health literacy. Again, however, there needs to be a business case that links health literacy to behavior change and health outcomes, which is something he hoped the roundtable would explore further.

CONCEPTS IN CULTURAL COMPETENCE3

One definition of cultural competence, said Guadalupe Pacheco, is the ability of an organization or an individual within the health care delivery system to provide effective, equitable, understandable, and respectful quality care and services that are responsive to diverse cultural health beliefs and practices, preferred languages, health literacy, and other communication needs of the patient. In essence, he said, cultural competence is about patient-centered care as discussed in the IOM report Crossing the Quality Chasm (IOM, 2000), though that report did not explicitly discuss cultural competence.

The key concept that health care practitioners need to address, Pacheco said, starts with looking at health beliefs through the lens of the patient.

___________________

3 This section is based on the presentation by Guadalupe Pacheco, founder, president, and chief executive officer of the Pacheco Consulting Group, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

Some patients, for example, view illness as a punishment from God, or the result of getting the evil eye from someone. Some cultures treat illness as an issue of fatalism, that illness and death are just part of life, that they happen for a reason, or that it was just someone’s time to die. Another concept is to address the communication needs of the patient with regard to language preference and health literacy, as well as how different cultures treat authority figures and the effect that has on asking questions. As an example of the latter, Pacheco said he was raised to never question a doctor, priest, or teacher. The challenge, then, is to deal with those kinds of cultural perspectives in a way that breaks down communication barriers, he explained.

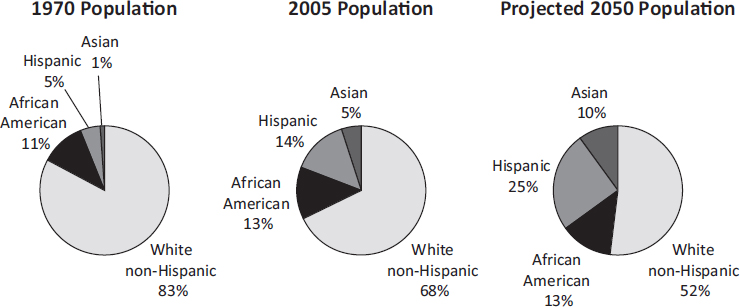

A third key concept is providing culturally competent care, which falls into the realm of providing patient-centered equitable care, Pacheco noted. The final concept he listed was developing a workforce that is inclusive of the demographics of the community, something that is taking on increasing importance with the changing demographics of the United States (see Figure 2-2). Pacheco called this population trend a game changer in terms of the strategies that health care providers are going to use to reach the different racial and ethnic minority groups that combined will account for 48 percent of the U.S. population by 2050. It is obvious, he said, that these strategies will have to be culturally competent to be successful.

Another game changer, said Pacheco, is the increasing recognition of the health disparities that affect many groups in the United States. “Why are we developing culturally competent programs and initiatives and health literacy initiatives? Because we want to deal with health disparities,” said Pacheco. Half of the nearly 29 million Americans with diabetes belong to various minority groups, he noted, and the majority of children considered to be obese are Latinos and African Americans. In both cases, poverty,

SOURCE: Presented by Pacheco, October 19, 2015.

lifestyles, and environmental factors are to blame for these major drivers of health care costs, which again ties back to health inequities. Pacheco cited a 2006 study (LaVeist et al., 2011) estimating that limiting health disparities would reduce direct medical expenditures by almost $300 billion and that premature deaths from health disparities cost the nation some $1.24 trillion. He also noted that approximately 35 million U.S. residents are foreign born, approximately 55 million people (19.7 percent of the U.S. population) speak a language other than English at home, and more than 25 million people (8.7 percent of the U.S. population), speak English less than “very well” and are considered to have low English proficiency.

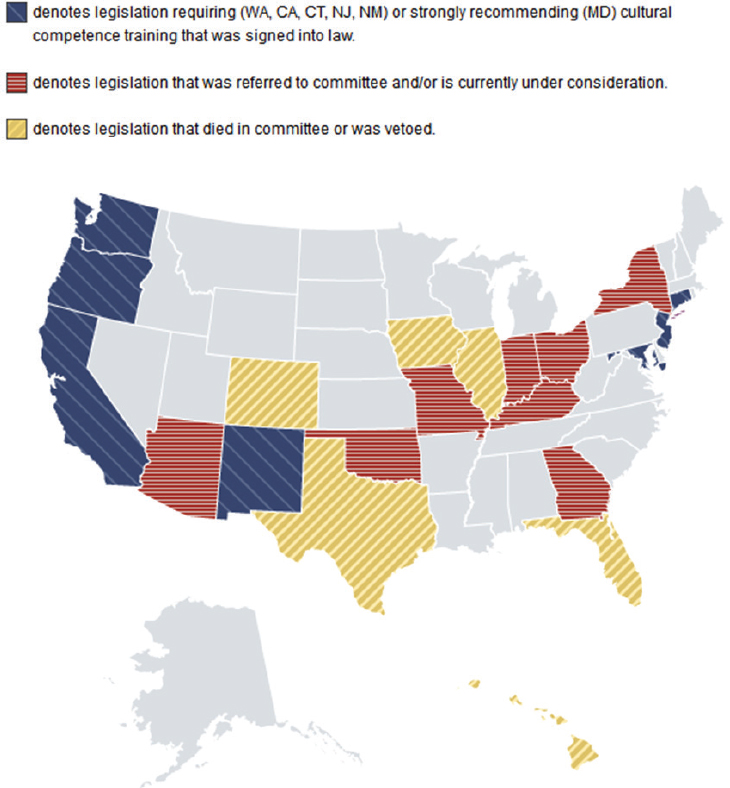

With regard to policies pushing the cultural competence and health literacy agenda, Pacheco referred to the CLAS standards that were first issued in 2000 and reissued in 2013. The 15 standards in CLAS provide pathways for the delivery of culturally competent care to diverse populations. He also cited the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of Civil Rights guidance, issued in 2000 and again in 2003, regarding Title VI of the Civil Rights Act’s prohibition against national origin discrimination affecting those who have low English proficiency, and the ACA, which has 19 provisions addressing culturally competent care and health literacy. Another driver was the established standards of The Joint Commission and the National Committee for Quality Assurance addressing communication, cultural competence, patient-centered care, and the provision of language assistance. At least seven states have passed legislation mandating some form of cultural competency requirements in their health care delivery system, another eight states are considering such legislation, and in five states legislation was introduced but died in committee or was vetoed (see Figure 2-3). As a final comment, Pacheco noted that the number of publications on cultural awareness and the number of citations has risen since 2001. “If you pick up any report dealing with health equity, you will find reference to cultural competency trends and progress,” he said in closing.

LANGUAGE ACCESS SERVICES4

To illustrate the central challenge that language access presents in the health care environment, Wilma Alvarado-Little began her presentation with a quote from George Bernard Shaw, who said “The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place.” She then addressed the difference between language access and language assistance. According to the HHS Language Access Plan issued in 2013, language

___________________

4 This section is based on the presentation by Wilma Alvarado-Little, principal and founder of Alvarado-Little Consulting, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

SOURCE: HHS Office of Minority Health, 2015.

access is achieved when individuals with low English proficiency can communicate effectively with HHS employees and contractors and participate in HHS programs and activities. Language assistance refers to all oral and written language services needed to assist individuals with low English proficiency to communicate effectively with HHS staff and contractors and gain meaningful access and equal opportunity to participate in the services, activities, programs, or other benefits administered by HHS. In summary, language access, explained Alvarado-Little, focuses on equity, and language assistance focuses on the methods of service delivery, whether

it be in-person sign language or spoken language interpreters, video remote interpreting, or remote simultaneous medical interpreting.

Alvarado-Little noted that when she speaks about language access services, she is often surprised by how many people are unaware of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, the Office for Civil Rights, the Americans with Disabilities Act, Executive Order 13166, and the U.S. Department of Justice guidance for agencies for developing language access plans to ensure meaningful access to services for individuals who have low English proficiency and includes what is known as the four-factor analysis5 for assessing whether recipients of federal funds and federal agencies meet the requirements. She also tries to drill down to find out more information regarding her audiences’ knowledge by asking, for example, what they know about the policies of their own states or organizations, the demographics of those they serve, and the top five languages their clients or patients speak. She recounted how she recently asked officials at a hospital in rural upstate New York if they were complying with The Joint Commission accreditation requirements on language access and their response was that they were not accredited by The Joint Commission so they were off the hook. Though not true, that response illustrates a glaring lack of knowledge about relevant regulations and policies concerning language access services.

Another key concept, said Alvarado-Little, is the need to educate health systems about the role of the interpreter or translator, roles that are not interchangeable. Interpreting, she explained, applies to oral communication and requires strong listening and speaking skills, while translating applies to written communication and involves reading and writing skills. Alvarado-Little noted that a good interpreter is not part of the conversation between two individuals. She also explained that members of the health care team should brief the interpreter about specialized vocabulary they might be using before meeting with the patient or family.

There are several certifications available for health care interpreters, such as the Certification Commission for Healthcare Interpreters, the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, and the National Board of Certification for Medical Interpreters, and for the medical translators who deal with discharge instructions and other written materials. Certification, however, is

___________________

5 Four-factor analysis is the first step in determining whether individuals with limited English proficiency (LEP) have meaningful access to programs. The factors considered are (1) the number or proportion of LEP persons eligible to be served or likely to be encountered by the program or grantee; (2) the frequency with which LEP individuals come into contact with the program; (3) the nature and importance of the program, activity, or service provided by the recipient to its beneficiaries; and (4) the resources available to the grantee/recipient and the costs of interpretation/translation services (http://www.hhs.gov/civil-rights/for-providers/laws-regulations-guidance/guidance-federal-financial-assistance-title-VI/index.html [accessed June 7, 2016]).

not available for all languages. Therefore, health care systems need to look closely at the level of formal education and type of training an individual has had. Alvarado-Little noted that interpreters also follow a code of ethics and standards of practice.

Having a certified interpreter and not merely a family member present is particularly important when interpreting preoperative instructions and working with terms such as health proxy, advance directives, and living wills, concepts that do not exist in some countries and cultures, as well as terms such as copay, deductible, out-of-network, and out-of-pocket. Medication regimes can often be complicated, and having a certified interpreter who is experienced in dealing with different levels of health literacy and culture, different measurement systems, and knows that some medications go by different names in different countries can mean the difference between a patient and family truly understanding what is being said to them and misunderstanding instructions that are given at a particularly stressful moment. When trained interpreters and translators are not used, the result is often miscommunication. Some institutions, for example, attempt to turn English words into Spanish by adding an o to the end of the English word, with the English word exit becoming the Spanish word éxito, which actually means successful, rather than salido, the real Spanish word for exit.

Turning to her third key concept, community engagement and empowerment, Alvarado-Little said that the main focus here is educating end users—the patient, provider, workforce, and community member—about the need to understand what is involved in providing or using language access services and the mandates to do so. It is important, she said, to empower communities to know it is their right to have an interpreter present in any interaction with the health care system and for providers to know that interpreters are there to be their partners in providing health care to those who need such services. Communities need to feel empowered, she added, to ask that the materials they receive from the health care system be reviewed for cultural competence and to expect that health care providers will make use of an interpreter rather than just speaking more slowly and louder when talking to someone who does not speak English or who is hard of hearing or deaf. Alvarado-Little also said interpreters expect to be treated with respect as professionals and to be called by the appropriate title. “We are not interpretives, interpretators, or interpolators, and we are not translators,” she said.

She then cited three resources that she said have helped her move the discussion forward when she speaks with health care systems about turning policy into practice:

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: https://www.healthcare.gov (accessed June 3, 2016)

- Attributes of a Health Literate Organization: http://nam.edu/perspectives-2012-attributes-of-a-health-literate-organization (accessed June 3, 2016)

- HHS Office of Minority Health’s National Standards on Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services: http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=2&lvlid=53 (accessed June 3, 2016)

These three documents, she said, enable her to say that this is not just about the health literacy community saying that providing language access services and culturally competent communications is something that health care systems should be doing, but that there is substance involved. What still needs to happen, she said, is for the health literacy community to get the message out about the importance of integrating health literacy, cultural competence, and language access services and for there to be continued enforcement and evaluation. “Patient-centered care is communication based and is about addressing issues contributing to health disparities,” Alvarado-Little said in closing. “When we do not speak the language of the individual, we must use an additional set of skills to continue to provide excellent patient care.”

DISCUSSION

Rosof began the discussion by wondering if business case was the wrong term to use when thinking about cultural and language competence, and if the field should be talking about return on investment. He illustrated this difference by saying that when North Shore–Long Island Jewish (LIJ) Health System opened the Dolan Family Health Center 20 years ago, the chief financial officer said there was no business case that would justify investing in a facility to provide care for a largely vulnerable and uninsured population with a variety of cultural competency issues. He was right, said Rosof, because to this day, North Shore–LIJ still loses about $600,000 per year. He estimated, though, that the return on investment in terms of a healthy community, healthy population, and thousands of healthy children must be sizable.

Wolf agreed with Rosof and said health systems are starting to look at what would be an acceptable cost for realizing those community health benefits. He recounted that when he was in the process of convincing one of the largest national pharmacy chains to undertake a health literacy initiative, the executives of this company had several questions they wanted answered: Are we getting ahead of an eventual mandate? Are we going to sell more product? Is there a way to frame this as a safety initiative? With regard to this last question, Wolf said while some health systems are framing health literacy, cultural competence, and access to language services in terms of

a risk-mitigation strategy for specific subgroups, he thought this is a bad strategy for the health literacy field. “We want to have people thinking that this is a right thing to do, that they are going to get return on investment, and that it is a matter of improvement in health care quality,” said Wolf. Yes, he added, there will be some safety-related benefits, but in his mind health literacy, cultural competence, and language access services should be viewed as quality indicators and an integral part of value-based design.

Andrulis agreed with Wolf and noted the importance of getting past a pure dollars-and-cents, bottom-line business case and looking instead at bigger issues that can lead to an expanded version of the business case. Examples he cited included the cost of hospital readmissions and physician follow-up visits resulting from the health care system not paying attention to health literacy or cultural or language issues, the expense of not complying with regulations, or the penalties for performing poorly on metrics of patient satisfaction and quality of care. Pacheco added that a key element in building an expanded business case is data collection. “Analytics is driving policy and programs,” he said. If health care systems started documenting how health literacy, cultural competence, and language issues are acting as barriers for patients getting to a clinical encounter and following care plans, it would provide the leverage to build a business case that more accurately reflects the larger value of health literacy, cultural competence, and language access services.

Ruth Parker from Emory University School of Medicine asked the panelists if they knew of anyone who was writing about literacy, language, and culture from the perspective of value, given how value is high on the agenda of health care systems. Andrulis said that he did not know of anyone who has approached the business case in that way. “That is why I think the timing of this workshop is important in the sense of reevaluating the visibility of language, literacy, and culture and grounding them in data,” said Andrulis. He proposed that the National Institutes of Health (NIH) should fund a series of demonstration projects or assessments comparing results from experimental and control groups to produce a foundation grounded in data and real-life experience, not just anecdote and advocacy. He added that with all of the projects going on today involving enrollers and assisters, who he assumed are engaging in health literate, culturally competent, language-appropriate outreach activities, he has yet to see any studies looking at those efforts. Alvarado-Little noted both the importance and the difficulty of capturing the effect of providing language access services compared to not providing them. As an example, she cited a recent instance in which a patient had been briefed in the absence of an interpreter prior to surgery. This patient had not understood the instructions and was missing a laboratory test required by New York State. Fortunately, an interpreter encountered this patient and informed him about the need to have this test

run, and so the patient was ready for surgery on the appointed day. “But how do we capture what would have happened if he had shown up and had the surgery cancelled?” asked Alvarado-Little. “That is a question I know we are not going to answer today, but it is one we need to think about.”

Rima Rudd from the Harvard School of Public Health offered a brief comment on why she has not successfully grappled with the issues of culture, language, and literacy and integrating them. With issues of culture, it seems to her that the health care system takes for granted its interpretation of health, medicine, and nursing as the base culture and then tries to learn the culture of its patients. “I think we need a deeper analysis of what our culture is and to understand what our biases are, what our limitations are, and what our values and assumptions are before we can really understand another culture,” said Rudd.

To her, these are issues of explaining and negotiating, which is about good communication. “When we think about interpretation, the ethics of a good interpreter is to be true to the statement that is being made,” said Rudd. Being true to the statement requires negotiating for the extra time and effort required beyond that needed for the mere change from one language to another given the complexities of explaining the meaning of medical jargon. She often thinks of the scene in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass when Humpty Dumpty says to Alice that when he uses a word it means exactly what he wants it to mean, which to Rudd means there is no room for interpretation or explanation. “Of course, we know what happened to Humpty Dumpty, and I am worried that the same thing will happen to us.” In some ways, she continued, integrating health literacy with culture and language services cannot happen without a lengthy, detailed explanation, negotiation, and respectful dialogue.

Given that context, Rudd asked Alvarado-Little what she means by language access. Alvarado-Little explained that interpreting for providers can be tricky given that whatever she hears, she is obligated by her code of ethics to interpret. To answer Rudd’s question in what she characterized as a roundabout way, she described how she was interpreting for a complex patient in the intensive care unit who was heavily sedated for his protection. The patient’s family arrived and she was interpreting for his sister, who was his health care proxy. The nurse asked if the family had any questions and the sister asked why her brother’s hand was so swollen. The nurse replied it was the result of a physiological response, and Alvarado-Little interpreted that even though she herself did not know what it meant. “The sister looks at me, the nurse looks at me, and I am supposed to be transparent, so I say nothing,” said Alvarado-Little. Finally, the nurse looked back at the family and said that was the only explanation she had. At that moment, Alvarado-Little stepped out of her role as a transparent conduit and asked for permission to clarify something with the nurse. Turning to the nurse,

she asked, “As an interpreter, is there something else you would like me to interpret, such as do you have any other questions?” Her position was that she did not want to do anything that would cause the nurse to lose face. The nurse then turned to the sister and asked if she understood, which Alvarado-Little interpreted, and the sister replied no, she did not know what a physiological response meant.

In that instance, Alvarado-Little explained, she applied her cultural competence and knowledge about health literacy while still adhering to her code of ethics to help bridge a gap that was preventing effective communication. “I am not responsible, nor would I pretend to be responsible, for the words of others,” she said, “but what I can do as somebody who is trained in this area and always learning is to try to be a resource when I am the only one in the room with a foot in both worlds.” What would help avoid this type of situation, she added, would be for the health care professional to be aware of what they are presenting and the challenges that someone outside of the profession might have understanding that information.

Pacheco responded to Rudd’s question by noting that health literacy and cultural competence are about communication and making sure the patient understands all of the information being conveyed. Addressing Rudd’s comments about culture, he said the culture of a federally qualified health center is much different from that of a typical hospital. The federally qualified health center has staff that represents the surrounding community, it has interpreters and materials translated into the languages used in the surrounding community, and it has community health workers and patient navigators who know about and understand the cultural and language diversity in the surrounding community. It would be useful, he said, to study the strategies and interventions these federally qualified health centers use to address the needs of those diverse populations and think about how those practices might be adopted or adapted for the hospital setting to address the needs of those patients that have chronic diseases. Rosof summarized this part of the discussion by referring to the earlier Shaw quote, saying that the biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it is taking place.

Laurie Francis commented that she works exclusively with federally qualified health centers in her role with the Oregon Primary Care Association and that she is mildly and chronically irritated with how much work still remains to bridge the health literacy world with the patient-centric world. She then remarked that culturally competent providers would be better listeners, inquirers, and interviewers, particularly for patients who come from cultures that would never think of questioning a doctor or other provider given the inherent power differentials in health care. Her question for the panel was whether they thought it was time to go from lecturing gently about the need to be health literate, culturally competent, and pro-

vide language access services to calling out the provider team, particularly their need to listen and not just lecture, in the same way that health care systems are being brought to task around issues of equity.

Andrulis replied that yes, it is time to do just that because this is at its heart an issue of being conscious about these issues. It is time for health care professionals to recognize that health literacy, cultural competence, and language access services have to be a part of the narrative around patient care. Bringing these elements to a discussion should not be an assumption, but a requirement that gets documented, which in turn would begin generating the data that Pacheco said are needed to develop more effective approaches for communicating with patients, families, and communities. Andrulis suggested the health care marketplaces created by the ACA may have some important lessons for how to integrate these three concepts, particularly with regard to training, documentation, customer satisfaction, and measurement. He suspected, in fact, that the marketplaces may be further ahead than the rest of the health care field because they have been forced to by the plain language requirements in the ACA. He also repeated Parker’s point about documenting where value is playing out in new initiatives to better understand how to develop more effective programs.

One challenge regarding patient-centeredness, said Wolf, is that little is known about the characteristics of patients, including their health literacy skills, language preferences, and cultural backgrounds, that affect their engagement in health care, which in turn makes it difficult to create a more efficient and patient-centered health care system. Getting this kind of information goes beyond the 15- to 20-minute encounter and requires building a real relationship between the patient and the provider and a recognition from the health care system perspective that this is a worthwhile endeavor. Until that happens, he said, there will continue to be stagnation in terms of truly creating a more efficient and responsive health care system.

Michael Paasche-Orlow from the Boston University School of Medicine echoed Francis’s suggestion that it is time for the health literacy field to drop the gentle approach to convincing health systems to become health literate and culturally competent, and provide language access services as the standard of practice. He acknowledged that some changes will require data, and he applauded Andrulis’s call to learn from approaches that work. Other changes, however, require direct advocacy. “What are we thinking when we see patients that we cannot talk to in the same language? What are we doing in that appointment?” asked Paasche-Orlow, who places the blame for what is obviously wrong with that situation on the provider-centric cultural belief that dominates physician attitudes. He acknowledged that the health literacy community needs to learn how to be more forceful in its advocacy, and the time to learn how to do so is now. He noted it is still uncommon for clinicians to call upon professional interpreters when meet-

ing with patients who speak a different language, and that while it is important to hear about how a professional interpreter such as Alvarado-Little will step out of her role as interpreter to make sure effective communication is occurring, it is the exception rather than the rule that she even had the opportunity to be in the room with the patient and provider. “This should be a matter of a patient’s civil rights in this country,” said Paasche-Orlow.

Pacheco said what has been missing is the progressive element in health care, and looking at this issue in terms of civil rights is a promising approach. He called on the workshop attendees to push the Office for Civil Rights at HHS to start enforcing its guidance and laws that affect the civil rights of individuals who are trying to access health care but cannot because of issues involving health literacy, cultural competence, and language access services. He added that he believes there is movement in the direction of more forcefully addressing these issues. Paasche-Orlow said this community needs to bring anger in addition to advocacy to bear on addressing these issues, though Andrulis said that what is needed is passion, not anger. “My goal is to find the tools that you, I, and others can use to advocate passionately and in a way that convinces people,” said Andrulis.

Alvarado-Little said that when she goes into a room as an interpreter, she also goes in wearing her masters in social work hat when she works with those providers who have fragile egos regarding self-assessment and language. When she deals with medical students, she reminds them to think about whether they ask their patients what language they get sick in and to access their emotions. She commented that nutrition is a hard area in which to interpret because food names can vary tremendously even within one language, such as Spanish, because of cultural factors. Speech pathology is another area where interpreting is difficult because of how the tongue and lips are used in different languages. The key, she said, is preparation, of learning what words make sense to a patient and that are diagnostic for the speech pathologist. Mental health appointments can also be challenging because conversations can be “word salads” rather than linear. She recounted one instance when she was interpreting for an adolescent who was having visual and auditory hallucinations. The provider said, “This is Wilma. You can touch her. She is real.” Alvarado-Little had to interpret that.

She agreed with the call to bring passion to this community’s advocacy efforts and noted that in some cases clinicians do not call for interpreters because they are not even aware that service exists in their health care system. She added that what she tells medical students is to use her to help them work smarter, not harder, and noted that interpreters often have to walk a fine line to avoid doing anything to undermine a patient’s confidence in his or her provider. “I have to be careful because if I do something that taints that relationship, the provider might not call me back and instead

use their own skills because they have generalized that interpreters are difficult,” Alvarado-Little explained.

Marshall Chin from the University of Chicago asked Wolf to comment more on why he thinks the three fields being discussed at this workshop have stagnated and what the single most important new direction he thinks these fields should take. Wolf replied that two important causes of stagnation, at least from the perspective of health literacy, are the health literacy community continues to do a poor job at disseminating best practices and the lack of a strong evidence base to support those best practices. In addition, he believes there are too many factions in the field. “We need to have a united voice,” he said. Wolf also commended the roundtable for talking about evaluation and laying out the characteristics of a good health literacy intervention.

Andrew Pleasant from the Canyon Ranch Institute commented that when it comes to making policy change, “numbers get you in the door, but stories win hearts and minds.” The ACA and PCORI, he explained, “are providing fabulous opportunities to advance health literacy, language access, cultural competency, yet they go out of their way to defer people—some would say prevent people—from using metrics such as the quality-adjusted life year to achieve the ends this group is trying to achieve.” He said that he has used the quality-adjusted life year metric to demonstrate clearly that health literacy and integrated health prevention interventions can create health at lower cost than most other medical interventions, but PCORI is prevented from funding research that makes cost comparisons. Given that situation, he asked the panelists how these fields can align strategically to change that discussion and enable the use of specific metrics to make the business case or show a return on investment.

Andrulis responded that there are some efforts to work around those restrictions, and the National Prevention Strategy and other initiatives are trying to address this roadblock. He noted this is a hard area for foundations to tackle because they do not want to spend the money. As an example, he said he is involved in the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s work to create a National Health Equity Index, and when he raises the need to include literacy, language, and culture in that index, the response is lukewarm because the focus is on other areas. He and his colleagues Brian Smedley of the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies and Steven Woolf at Virginia Commonwealth University are making it a point of advocacy to step up and make the case, but so far they have been unsuccessful at engaging those at the foundation who are creating this index. With regard to other efforts to produce supporting data, he suggested turning to Congress and finding allies within federal agencies to raise the visibility of the need for metrics and data. Pacheco noted there are sympathetic ears in Congress and also suggested approaching the White House about using

executive orders to address this issue strategically without harming entities such as PCORI. Alvarado-Little said the New York state legislature could not pass a language assistance bill, but the governor issued an executive order mandating supervision of language access services for the top six languages as identified by the 2010 U.S. Census. She and her colleagues are also working with the provisions of the New York State Pharmacy Act that require chain pharmacies to provide these services.

This page intentionally left blank.