4

Addressing the Challenges

The workshop’s third panel provided four examples of programs that aim to integrate health literacy, cultural competence, and language access services. Jessica Briefer French, senior research scientist with the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), addressed how issues of health literacy, cultural competence, and language access are being incorporated into national quality standards and measures. Sarah de Guia, executive director of the California Pan-Ethnic Health Network (CPEHN), spoke about some of the legislative proposals and administrative advocacy that her organization has been involved with to advance integration. Marshall Chin, the Richard Parrillo Family Professor of Healthcare Ethics in the Department of Medicine at the University of Chicago, discussed his experiences directing the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Reducing Health Care Disparities through Payment and Delivery System Reform program office and some of the successful interventions incorporating concepts of health literacy, cultural competence, and language access. The final speaker, Stacey Rosen, associate professor of Cardiology and vice president for Women’s Health at the Katz Institute for Women’s Health, Hofstra North Shore–LIJ School of Medicine, described ways her health system and how some state-level health transformation efforts have been incorporating these concepts into their operations. An open discussion, moderated by Ignatius Bau, an independent health care policy consultant with Health Policy Consultation Services, followed the four presentations.

INTEGRATING HEALTH LITERACY, CULTURAL COMPETENCE, AND LANGUAGE ACCESS INTO QUALITY IMPROVEMENT STANDARDS AND ACTIVITIES1

NCQA is a nonprofit organization that measures and evaluates health care quality with the mission of improving the quality of health care, explained Jessica Briefer French. NCQA is probably best known, she said, for its accreditation programs for health care plans and accountable care organizations (ACOs), the HEDIS, and its recognitions programs for patient-centered medical homes and specialty practices. Its accreditation programs for some 1,200 health plans and ACOs, including a multicultural health care distinction program focused specifically on issues of cultural competence, language access, and health care disparities, are probably the most relevant for this workshop. She noted that the HEDIS data set includes submissions from more than 1,100 health plans, including commercial, Medicare, and Medicaid plans. Approximately 950 of these are publicly reporting health plans, and the rest are nonpublicly reporting plans that allow NCQA to include their data in aggregate but without identifying them individually. NCQA’s recognition programs for patient-centered medical homes covers 11,000 operations and approximately 100 specialty practices. All of these programs integrate NCQA’s CLAS standards.

For its health plan accreditation program, NCQA uses standards included in its multicultural health care distinction program, though the health plan program has a broader focus and addresses standards in other areas, too. The multicultural health care distinction program focuses on standards that address CLAS and disparities, but it does not address health literacy. The health care accreditation plan has fewer standards related specifically to CLAS, but it does address health literacy throughout in the form of requirements to provide information in understandable language. Both plans have a strategic focus, explained French. The health plan accreditation program specifies objectives for serving a culturally diverse membership, as well as eight other objectives. The multicultural health care distinction program has the same objective for serving a culturally diverse membership as well as additional requirements such as a process to involve members of the diverse community and a list of measureable goals for improving CLAS.

Both programs, said French, have comparable standards for cultural competence of the health care network requiring assessment of cultural, racial, and linguistic needs of its members and adjusting the availability of practitioners based on that assessment. The multicultural health care dis-

___________________

1 This section is based on the presentation by Jessica Briefer French, senior research scientist with the National Committee for Quality Assurance, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

tinction program also requires a network to collect and publish information about its practitioners’ language skills and the network’s language services to ensure that the right languages are represented in the network and that there is transparency for the network’s members.

The two programs also have different levels of specificity with regard to language services, French added. The health plan accreditation program requires plans to provide language services for members and for complaints and appeals processes, and to provide information on how to obtain language assistance. The multicultural health care distinction program goes further in requiring translation of vital documents and provision of competent interpreter or bilingual services. She noted that at the time these requirements were written, interpreter and translator certification programs were just getting started, so it would have been premature at the time to specifically require certification. “Certainly, we intended through the language of the standards to allow for certification to satisfy that requirement,” said French. The multicultural health care distinction program standard also requires networks to support practitioners in providing effective language services.

With regard to quality improvement, the health plan accreditation program requires improvement, but it does not focus on CLAS, nor is it prescriptive about where health plans focus their improvement efforts. In contrast, the multicultural health care distinction program requires a focus on measurement and improvement of linguistic and cultural competency and includes a mandate to evaluate the effectiveness of the interventions to improve language and cultural competency.

Data collection standards are included in both programs, said French. The health plan accreditation program requires reporting on a long list of selected HEDIS measures related primarily to effectiveness of care but not specifically related to CLAS. The multicultural health care distinction program requires data collection on race, ethnicity, and language needs, and it requires reporting on the two HEDIS measures of diversity, which are the preferred language for spoken communication and written materials and the racial and ethnic composition of the membership. The intent of having plans capture those data is to enable them to measure and report on disparities and conduct studies involving stratification, explained French.

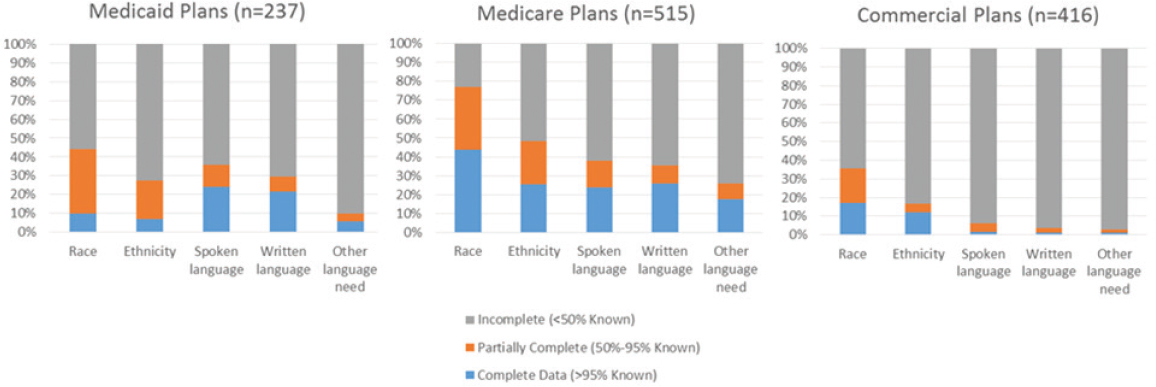

French noted that reporting on these two HEDIS measures of diversity is voluntary for the health plan accreditation program, and NCQA has had “less than exciting results on these measures,” with low levels of information reported by health plans about race, ethnicity, and languages of their members (see Figure 4-1). Medicare plans, she added, have done better at reporting race, ethnicity, and language needs than commercial plans. She noted that it is a continuing challenge to capture these data.

The patient-centered medical home and specialty recognition programs also include standards related to cultural and linguistic appropriateness.

SOURCES: NCQA, 2015, presented by French, October 19, 2015.

To receive recognition, a practice must understand and meet the cultural and linguistic needs of its patients and families by assessing the diversity and language needs of its population, providing interpretation or bilingual services to meet the language needs of its population, and providing printed materials in the languages of its population. Practices also must use an EHR to record patient information as structured data on race, ethnicity, and preferred language, and to assess health literacy. The most recent data, explained French, were collected for standards issued in 2014 (see Table 4-1). She noted that a survey of some 1,100 practices based on the 2011 standards had slightly lower but still high performance on these measures. The key takeaway, said French, is that providers are doing a good job of capturing information about race, ethnicity, and language needs, but not quite as good a job of assessing health literacy, though more than half of the providers are assessing health literacy. She noted that it helps that these measurement requirements are part of the meaningful use incentive program.

The lesson from these results is that there are measures and standards related to cultural competence, language access, and health literacy. These standards, said French, are available and are embedded in popular, longstanding voluntary programs. “What we have found is that purchaser and regulatory incentives make a huge difference in the uptake of these programs. On the provider side, the alignment with meaningful use makes a huge difference.” There is a synergy, she added, when there are incentives for doing things that are part of an otherwise larger and potentially dilutable set of standards. She noted that California is considering making the multicultural health care distinction program a requirement for its

| Functional Requirement | Patient-Centered Medical Home (N = 420) | Patient-Centered Specialty Practice (N = 95) |

| Assessing the racial and ethnic diversity of its population. | 96.7% | 87.9% |

| Assessing the language needs of its population. | 98.3% | 80.2% |

| Providing interpretation or bilingual services to meet the language needs of its population. | 98.6% | 94.5% |

| Providing printed materials in the languages of its population. | 77.1% | 63.7% |

| Assessing health literacy. | 58.3% | N/A |

SOURCE: Presented by French, October 19, 2015.

health plans. Currently, only 16 organizations hold the distinction of being recognized by this program, making it clear, she said, that more leverage is needed. However, a recent study NCQA conducted for the Office of Minority Health at CMS found that there is delivery system reform fatigue. “There are so many reforms under way, so much effort to transform the health care system, and many of these efforts have incentives attached to them, such as pay-for-performance and a variety of value-based purchasing incentives,” said French. In this environment, organizations reported they are “following the money,” which she said means that systems will be more likely to focus on issues of culture, language access, and literacy when there are incentives that are at least equal to those for all of the other reforms they are being asked to make.

In closing, French said there is real opportunity from a regulatory and purchaser perspective to channel efforts and raise awareness of these issues, but not without advocacy. “As we heard earlier in the discussion, passion and advocacy are what is going to make purchasers and regulators bring these issues into their incentive and value-based purchasing programs,” said French.

STATE LEGISLATIVE APPROACHES TO INTEGRATION2

The 23-year-old CPEHN was founded during an era of health care reform by four partners—the Asian & Pacific Islander American Health Forum, the Latino Coalition for a Healthy California, The California Black Health Network, and the California Rural Indian Health Board. These organizations felt that communities of color or ethnicity needed to come together to provide a unified voice on health care reform, explained Sarah de Guia. Today, CPEHN is engaged in implementing the ACA with the goal of not just improving access to health care but also ensuring the data are available to inform decisions about where to deploy resources and to support reform efforts. CPEHN is also looking at the provision of culturally and linguistically appropriate health care services and addressing some of the social determinants of health, de Guia added.

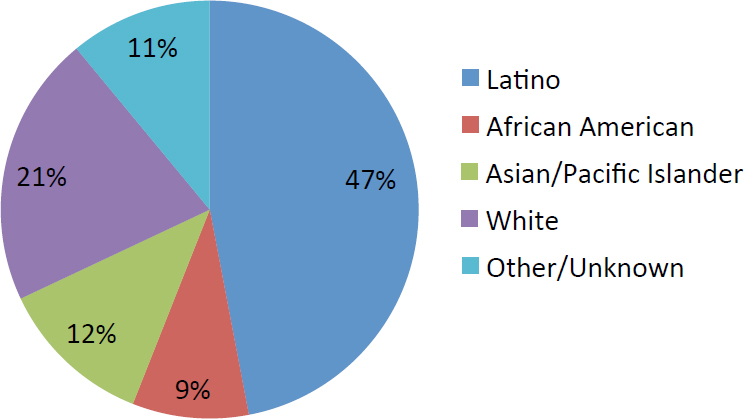

As a means of providing context for why CPEHN believes its work on legislative and administrative advocacy to promote change is important, de Guia briefly reviewed some pertinent demographic data. California, she said, has one of the most diverse populations in the nation, which is reflected in both ethnicity (see Figure 4-2) and language (see Table 4-2) of the state’s Medi-Cal (the California Medicaid program) enrollees. In

___________________

2 This section is based on the presentation by Sarah de Guia, executive director of the California Pan-Ethnic Health Network, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

SOURCES: California Department of Health Care Services, 2015, presented by de Guia October 19, 2015.

TABLE 4-2 Limited English Proficient Population Enrolled in Medi-Cal

| English Proficiency | Covered by Medi-Cal |

| Speaks English Very Well | 19.6% |

| Speaks English Well | 26.8% |

| Speaks English Not Well/Not at All | 34.7% |

SOURCES: 2014 California Health Interview Survey, presented by de Guia, October 19, 2015.

addition, communities of color account for 60 percent of the state’s residents who have purchased health insurance through Covered California, the state’s health insurance exchange, with Spanish, Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese as the top four non-English languages spoken by Covered California enrollees.

The 2014 California Health Interview Survey found that individuals with language issues have limited access to both primary and specialty care (see Table 4-3), and as a result individuals with limited English proficiency tend to rate their health as being poor or fair more often than their English-speaking counterparts (see Table 4-4).

Taken together, these demographic data point to why CPEHN advocates for the importance of language assistance standards in California’s Medi-Cal

TABLE 4-3 Access to Primary and Specialty Care by English Proficiency

| English Proficiency | Difficulty Finding Primary Care | Difficulty Finding Specialty Care | Does Not Have Usual Source of Care |

| Speaks English Very Well | 5.4% | 13.7% | 18.7% |

| Speaks English Well | 6.6% | 8.7% | 20.4% |

| Speaks English Not Well/Not at All | 3.8% | 16.7% | 27.2% |

SOURCES: 2014 California Health Interview Survey, presented by de Guia, October 19, 2015.

TABLE 4-4 Health Status by English Proficiency

| English Proficiency | Fair or Poor Overall Health |

| Speaks English Very Well | 15.9% |

| Speaks English Well | 20.3% |

| Speaks English Not Well/Not at All | 43.9% |

SOURCES: 2014 California Health Interview Survey, presented by de Guia, October 19, 2015.

program and commercial health plans, said de Guia. The Medi-Cal program, for example, has translation thresholds based on the number of enrollees in a county or zip code, as well as a requirement for interpretation services at any time in any language. Commercial plan translation thresholds are based on enrollment numbers, while interpretation services are required in any language during business hours, which de Guia said has presented challenges at times. Legislation regulating commercial health plans also requires the plans to collect race, ethnicity and language data, which de Guia noted gets to the point that French made about incentivizing or mandating data collection. There is some flexibility in this data collection requirement in that plans can impute some of the ethnic and racial percentages based on Census data, so CPEHN is working with plans to ensure they build race and ethnicity data collection into their systems so they can report actual figures rather than imputing them. She also pointed out plans are now required to report these data to the California Department of Managed Health Care (DMHC), and that DMHC surveys the plans to ensure they are actually providing the required translation and interpretation services.

Noting that it took several years and quite a bit of work to achieve these successes, de Guia said one thing in their favor was that the state’s public programs had some of these standards in place. “With 3.4 million enrollees with low English proficiency in private coverage, we were able to make the case that rather than just letting the market decide, we should

have standards in place about how plans would provide their language assistance services,” said de Guia. She also credited the strong leadership within the newly created DMHC for its role in pushing for the adoption of these standards and for legislative leadership in enacting California SB-853, which included the translation thresholds, language assistance, and data collection requirements for commercial plans. Recently, she added, the state codified into law the Medi-Cal thresholds, which since the mid-1990s had been included in contract language. “This provides us with more leverage for enforcement,” explained de Guia.

Unfortunately, de Guia noted, there was little in SB-853 regarding health literacy standards. “All of the culturally competent provisions were taken out of the bill during a very difficult negotiation process, and the new head of DMHC was not quite as consumer friendly as was the original director,” she explained. In addition, public programs were exempt from the requirements in SB-853, which points to the fragmentation that exists in the system. “We cannot get everything aligned,” said de Guia.

One thing CPEHN has been able to accomplish is to get the state to provide advance copies of applications, marketing materials, and notices so members of the coalition and the community-based organizations they work with can review them and provide some guidance. For example, a review of the Covered California application found that the Hmong translation was completely inaccurate and that the term marketplace was difficult to translate into Tagalog and Spanish. Concepts such as family size and lawful residency, key inputs that determine the type of coverage an individual or family was eligible for, were not accurately conveyed in Vietnamese. Based on these reviews, the state made changes to the translated application forms, de Guia said.

The broad coalition of organizations that CPEHN works with has been engaged in California policy making for several years now and has built a good, responsive relationship with DMHC. This coalition was involved in creating Covered California and helped include diversity provisions in Covered California’s board and set its goal to have its enrollees reflect the racial and ethnic diversity of the state. “We’re still working on that, but that goal is in the law,” said de Guia. CPEHN was also instrumental in creating a consumer workgroup that builds community engagement into Covered California’s operations and creates the mechanism by which notices are regularly reviewed by advocates. Nevertheless, the notices still continue to be too complex, largely because of statutory requirements to include certain information in every notice. In addition, the community engagement piece is not funded and is conducted largely by volunteers.

Over a decade ago, a study was conducted in California that raised concerns about medication adherence, and a task force was convened to examine this issue. While the initial focus was on the population at

large, the study and the task force noted the importance of low English proficiency and health literacy issues as contributors to poor medication adherence. California passed legislation in 2006 addressing some of these issues, but the compromise bill that was signed into law did not mandate translated prescription drug labels.

However, in 2010, the ACA was set to add 1.5 million individuals with limited English proficiency to the state’s health care system, which enabled CPEHN to once again raise this issue. At the time, said de Guia, the California Board of Pharmacy was working with researchers, including Michael Wolf, to identify health literacy issues with prescription labels and medication instructions. The idea, she explained, was to develop a set of standardized, simple instructions that would be easy to translate into other languages. In fact, the Board of Pharmacy worked with the California Endowment to provide translations of these standardized instructions in five languages. CPEHN helped write legislation that would have required pharmacies to use these translations, and when this bill did not go forward, the Board of Pharmacy took the issue on and did get legislation passed that was signed into law in 2015. Going forward, translated prescription drug labels are required in Spanish, Korean, Chinese, Vietnamese, and Russian. De Guia noted that California’s fifth most common language is Tagalog, but the bill included Russian based on national numbers.

A key issue CPEHN now hopes to address is that while there are standards in place for data collection and language assistance, enforcement is still a challenge. “Where is the hook to make sure providers understand their responsibilities, that health plans are complying with these standards, and that the departments themselves have the resources to be able to ensure that compliance is taking place?” asked de Guia. Also needed, she said, are evaluations of the programs that have been created. One evaluation did show that translated labels did increase comprehension for simple drug regimens.

CPEHN is also working to create alternative methods for surveying consumers with low English proficiency about their needs and experiences that go beyond CAHPS and similar surveys, particularly for individuals who do not speak the languages for which translated surveys are available. The organization is also focusing on developing a culturally appropriate workforce by incorporating promotoras and community health workers who can better address cultural competency in the health care system. As a final comment, she noted the importance of using community partners. “We do not have to be experts in all cultures and all languages,” said de Guia in closing. “There are many organizations that understand their communities’ needs and that can provide important insights into the needs of those communities that we are all seeking to serve.”

HOW CULTURAL COMPETENCE, LANGUAGE ACCESS, AND HEALTH LITERACY ARE INTEGRATED INTO PROGRAMS AND INTERVENTIONS AIMED AT REDUCING DISPARITIES3

Before turning to the main topic of his presentation, Marshall Chin said he agreed with Michael Wolf that the three fields of health literacy, cultural competence, and language access have the potential dangers of stagnating, being too insular, and too siloed. He also said that these fields have to do more in terms of integrating with existing quality and equity initiatives and do better at creating a business case while at the same time nurturing the inherent motivation and values people have for reducing disparities. He then noted that much of his presentation is based on the work of the 33 grantees and 12 systematic reviews of the health care disparities intervention literature funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Finding Answers: Disparities Research for Change, as well as the experience gained from providing technical assistance to a variety of organizations.

Based on the lessons learned from the Finding Answers program, Chin and his colleagues have developed a six-step roadmap for reducing racial and ethnic disparities in health care (Chin et al., 2012):

- Recognize disparities, and commit to reducing them.

- Implement a quality improvement infrastructure and process.

- Make equity an integral part of quality.

- Design interventions.

- Implement, evaluate, and adjust the interventions.

- Sustain the interventions.

The focus nationally, said Chin, has been on the first and fourth steps, but if the goal is sustained change, all six are needed. “We are not going to get there if we just focus on two of them,” he said.

Chin made two points about the first step, recognizing disparities and committing to reducing them. The first point was that performance data stratified by race, ethnicity, language, and socioeconomic status can be used to increase people’s motivation to change. “People have to see their own data to acknowledge there are disparities in their own practice,” said Chin. “They will not be motivated to change unless they are convinced there is actually an issue with their own particular patients.” His second point is that cultural competency programs have sometimes been too narrow and too insular, and that perhaps the emphasis should be on state-of-the-art

___________________

3 This section is based on the presentation by Marshall Chin, the Richard Parrillo Family Professor of Healthcare Ethics in the Department of Medicine at the University of Chicago, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

disparities training. The Society of General Internal Medicine, for example, has developed goals for health disparities courses that include discussing the existence and causes of disparities and working through various solutions for addressing mistrust, subconscious bias, and stereotyping. The courses should also work on communication and trust building and building a commitment to reduce disparities (Smith et al., 2007). Chin noted that while it is easy to get people to accept that addressing disparities is important, it is actually difficult to teach these courses well. “They can even be counterproductive if not taught well,” said Chin.

At the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine, the first two courses that first-year medical students take are anatomy and health care disparities. The disparities course (Vela et al., 2008) has been taught for some 10 years by Monica Vela, the associate dean for Multicultural Affairs, and on the first day of class she has the students go through a self-insight exercise that is an entrée into subconscious biases. The course includes field trips to Chicago’s south side, the home of most of the patients the students will see, so they can learn about their patient’s living environment, and a section on Chicago history where a sociologist talks about why housing in Chicago is segregated. The students learn that segregation did not occur by chance but because of a conscious set of policy and business decisions. The course also includes a group disparities project, in which small groups of students develop a disparities reduction process, as well as reflective essays and discussions that cover a gamut of topics including working with interpreters to learn about Medicare policy. Over the past 2 years, Vela has added a new segment on advocacy when she learned that without the advocacy component, students felt disempowered, which was counterproductive.

On a sobering note, Chin said, stratified data and cultural competency training alone do not improve clinical performance measures (Sequist et al., 2010). “Disparity interventions are helpful in raising awareness, and improving attitudes and knowledge, but they do not move the clinical numbers,” said Chin. “These interventions are helpful, but you have to combine them with other methods.”

Before describing some of those methods, he recounted a conversation reported in The New York Times (Haberman, 2015) between Hillary Clinton and Black Lives Matter activist Julius Jones. Secretary Clinton said, “You can get lip service from as many white people you can pack into Yankee Stadium and a million more like it who are going to say: ‘We get it, we get it. We are going to be nicer.’ That’s not enough, at least in my book. I don’t believe you change hearts. I believe you change laws, you change allocation of resources, you change the way systems operate.” Chin believes her statement may also apply to health care disparities, though he added that she does get some things wrong in that statement. “What

she gets wrong is that it is important to change hearts, to change people’s motivation. They have to really believe it and feel it is part of their social values to improve equity.”

“At the same time,” said Chin, “she is right that you have to change the laws, the allocation of resources, and the way systems operate.” He recalled speaking with some people from industry who made the point that to prevent disparity-reduction programs from becoming marginalized, they have to be embedded into the basic operating structure of people’s jobs. Doing so means making equity an integral component of quality improvement efforts. The challenge, though, is that too often the people who work on quality are not the same people who work on equity.

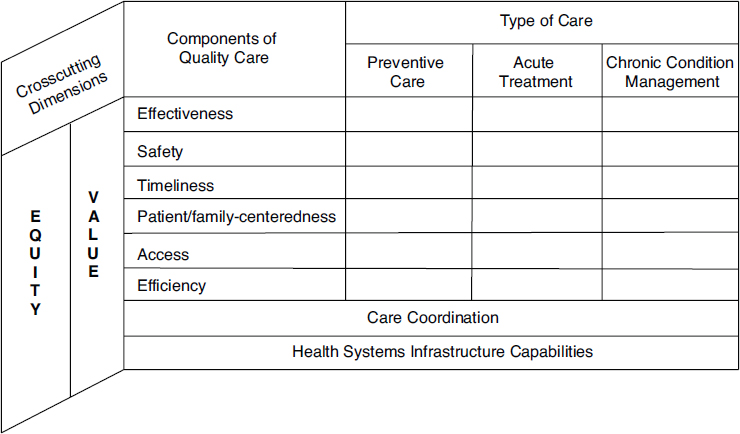

In 2010, the IOM reworked its Model of Quality and elevated equity from one of the six pillars of quality to something that cuts across all dimensions of quality (see Figure 4-3). This fundamental conceptual change says that equity needs to be a part of everything done to improve quality.

The fourth step on the roadmap calls for designing interventions that address the root causes of disparity and considers six levels of influence. Chin made the point that there is no substitute for talking to patients and community members, as opposed to talking to proxies such as minority health care providers. Too often, he said, the assumption is that African-American doctors or nurses are going to know what to do, but in fact, there is a good chance they come from different socioeconomic backgrounds

SOURCE: Presented by Chin, October 19, 2015.

than the patients that will be the focus of a program. As an example, Chin described a depression telephone intervention aimed at Latino patients that was designed after talking to Latino nurses and doctors. The intervention had trouble enrolling patients and the reason was that the target patients had pay-by-the-minute cell phone plans, as opposed to the unlimited minute plans that the doctors and nurses had.

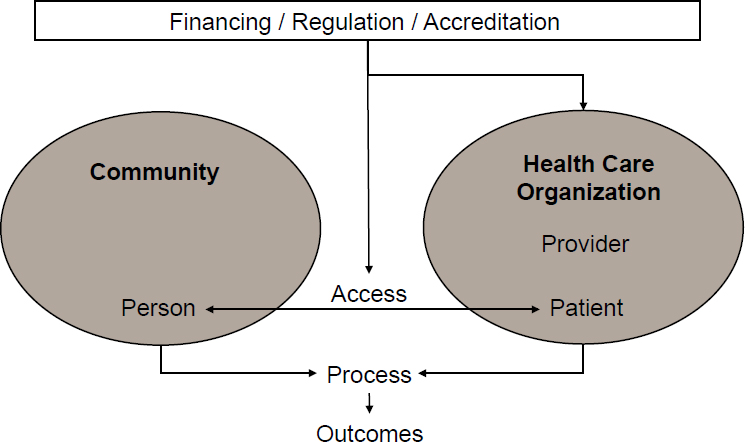

Chin then described a conceptual model for health care disparities (Chin and Goldmann, 2011; Chin et al., 2007) in which a person embedded in a community deals with access challenges to become a patient interacting with the clinician and health care organization (see Figure 4-4). Above that sits a policy superstructure that includes financing, regulation, and accreditation. Underlying the interaction between the patient, the health care organization, and the provider are processes and outcomes. Together, this model highlights six levels of influence: policy, the health care organization, the microsystem, the provider, the patient and family, and the community.

The policy level includes clinical performance standards linked to reimbursement or mandated by legislation. Such standards can be structural measures of culturally competent organizations such as interpreter use or clinical outcomes, or they can be equity index tools to rate organizations. At the level of the health care organization, there are various diversity, inclusion, and equity initiatives that institutions create, but the key is making these a true priority of senior leadership and providing the resources

SOURCES: Chin et al., 2007, presented by Chin, October 19, 2015.

and core team to facilitate change within organizations. These initiatives have to be embedded within existing committees and departments. Having a core team dedicated to an initiative makes a big difference in realizing the goals of the initiative, said Chin.

The microsystem is the immediate care team, and steps that can be taken at this level include integrating language services and interpreters more immediately into care teams. In these circumstances providers have easy access to these services and to training on how to be culturally competent, and on shared decision making. Patients and families also need help being empowered to participate in shared decision making and accessing language services. Finally, at the community level, it is important to empower the community through the more effective use of community health workers and to help communities address the social determinants of health.

An examination of 400 different interventions, Chin explained, shows there are not many magic bullets for success, though he and his colleagues identified six common themes among successful, evidence-based intervention strategies:

- Multifactorial interventions attacking different levers;

- Culturally tailored approaches are better than generic approaches;

- Team-based care, particularly when the teams are led by nurses;

- Involving families and community partners;

- Patient navigators; and

- Community health workers, along with interactive skills-based training.

The important point, said Chin, is that off-the-shelf tools are not going to work. Any successful intervention has to be embedded in the quality improvement process because there has to be adaptation to the individual context, culture, and patient setting. “There is going to be an important role for demonstrations and model programs, but there is always going to have to be adaptation,” said Chin.

He then briefly described a consolidated framework for implementation research (Damschroder et al., 2009). This framework comprises five major domains:

- Intervention characteristics that convey a relative advantage over the status quo,

- The external incentives,

- The culture of the organization,

- The characteristics and beliefs of the targeted individuals, and

- The process for planning, executing, and evaluating.

He also briefly discussed behavior change theory, which usually starts with educating people about why they should change and how it will solve a problem. However, said Chin, this is not how things work in the workplace, so it is necessary to consider the peer pressure and social norms that come with being part of a work culture. Other components of behavior change theory include environmental factors such as incentives and self-efficacy, which includes coaching, quality improvement collaboratives, and various approaches to give people the confidence they can change. Both internal motivations—professionalism and an appeal to do the right thing—and extrinsic motivations, including financial and other rewards, also play an important role in behavior change.

The final step on Chin’s roadmap is to sustain interventions, and that starts with institutionalizing them by ingraining them in the organizational culture, providing incentives, and integrating them into daily operations. It is also essential, though, to build the societal business case that reducing disparities will improve direct and indirect medical costs and help build a healthy, diverse national workforce. The direct business case aligns incentives with policy goals through global and bundled payments, and population health and pay-for-performance reimbursement models to reduce disparities is also key. He suggested other avenues for aligning policy with incentives would include better linkages between the community and the health care system and the community needs assessments required of nonprofit hospitals. Chin noted the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation has a program looking at using payment and delivery system reform to reduce disparities.

Recently, Chin attended a CMS conference. His impression from the discussions he heard is that CMS is doing great things with value-based purchasing, but not enough in terms of equity. He had a number of recommendations for CMS that he also thought were important for the roundtable. His first recommendation was to require public reporting of stratified disparities data, something that CMS is going to start in several of its programs over the next year. The second was to strengthen incentives for prevention and primary care. The current global payment and shared payment savings plans have been relatively modest, he said, and they need to be more aggressive to create more incentives to actually do prevention and primary care. “I think most of us know the relative value payment schedule for physicians is part of a political process as opposed to an evidence-based process, so the cognitive specialist and primary care physician are grossly undervalued,” said Chin.

To produce a greater financial incentive to work on disparities, Chin’s third recommendation was for CMS to encourage intersectoral health partnerships, explicit equity accountability measures, and provide specific reimbursements for reducing disparities. Fourth, CMS needs to align equity

measures across public and private payers and provide more support and more equitable reimbursement for safety net providers. “There needs to be risk adjustment for both clinical and social demographic factors to create a level playing field,” said Chin. “The bottom line is having an explicit equity lens both for quality efforts and payment efforts so we can think about how we design systems to reduce disparities.”

He concluded his presentation by stating that leadership matters (Chin, 2014). “It is our professional responsibility as clinicians, administrators, and policy makers to improve the way we deliver care to diverse patients. We can do better.”

EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION IN HEALTH CARE4

In the day’s final formal presentation, Stacey Rosen described what North Shore–LIJ Health System is doing to realign and integrate its efforts in health literacy, cultural competence, and language access. North Shore–LIJ Health System, which in 2016 will be renamed Northwell Health, is the 14th largest health care system in the United States. It comprises 20 hospitals, more than 400 ambulatory practices, and other health care, home care, long-term care, and hospice facilities. It is New York State’s largest private employer, and its 62,000 employees, including 10,000 physicians and 11,000 nurses, serve 8 million people on Long Island, the 5 boroughs of New York City, and Westchester County.

In 2008, the health system opened Hofstra North Shore–LIJ School of Medicine, the first new allopathic medical school established in New York State in 40 years. She noted that rather than immerse its new students in basic science classes, the medical school has them ride along with ambulance crews for the first 12 weeks, enabling them to learn about the social determinants of health in the underserved neighborhoods from which many of the health systems’ clients come. Rosen added that its newly opened nursing school for advanced nurse practitioners, and ultimately bachelor’s degree nurses, “turns nursing education on its head.” She noted, too, that North Shore–LIJ’s Center for Learning and Innovation is the largest corporate university in health care in the nation; it also runs the nation’s largest patient safety center. In New York City, the system recently opened the city’s first freestanding emergency department, as well as what Rosen characterized as a state-of-the-art community-based clinical practice in the Greenwich Village neighborhood.

___________________

4 This section is based on the presentation by Stacey Rosen, associate professor of cardiology and vice president for women’s health at the Katz Institute for Women’s Health, Hofstra North Shore–LIJ School of Medicine, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

Rosen noted that in Queens alone, some 175 languages are spoken on a daily basis, and until the system’s recent acquisition of two community-based hospitals that serve a predominantly white population, more than 40 percent of the system’s covered individuals did not speak English as their primary language, which she said is double the national average for health care systems. To address this diversity and also support the system’s business case, North Shore–LIJ Health System created the Office of Diversity, Inclusion, and Health Literacy in 2010. “There has been discussion today about the business case and return on investment, and you do have to align that with doing the right thing, but when margins get smaller and competing needs become an apparent financial concern, the business case is very important,” said Rosen.

The mission of the Office of Diversity, Inclusion, and Health Literacy, she explained, is to promote, sustain, and advance an environment that supports the principles of equity, diversity, inclusion, health literacy, and community. When this office opened, it began with a multiyear strategic plan to establish goals and steps to embed a culture of diversity, inclusion, and health literacy across the complex North Shore–LIJ system, including among its medical students and in the community it serves. As a first step, the office performed the American Medical Association’s community climate assessment toolkit survey at several of the system’s hospitals to better understand their cultural competency and health literacy awareness and readiness. The results of this initial survey informed the strategic plan, which focused initially on education and awareness. Rosen said that when this process started in 2010, diversity, inclusion, and health literacy efforts in the system were somewhat siloed, with health literacy efforts focused predominantly on education and awareness at several of the system’s larger hospitals and diversity and inclusion activities embedded in the new medical school curriculum.

While North Shore–LIJ was developing its strategic plan, HHS announced the new National Prevention Strategy focused on increasing the number of Americans who are healthy at every stage of life. System administrators decided then, said Rosen, to align two of the National Prevention Strategies four strategic initiatives—empowering people and eliminating health disparities—with the activities of the Office of Diversity, Inclusion, and Health Literacy. Health literacy fit into this focus because individuals who have access to actionable and easy-to-understand information become empowered to make healthier choices. Working toward eliminating health disparities, North Shore–LIJ focused on identifying communities at risk and engaging leaders in those communities when it developed programs with the goal of truly aligning those programs with local cultures in a way that reflected the unique features of the vast communities the system serves. With this new focus, the Office of Diversity, Inclusion,

and Health Literacy expanded its purview to include language access and cultural competency activities in addition to diversity, inclusion, and health literacy. Under the banner of effective communication, these activities aim to improve the interaction between an individual’s ability to access health care and the demands of the health care system itself.

One result of this new strategic focus was that the Office of Diversity, Inclusion, and Health Literacy took over all health literacy activities and evaluated every piece of patient education material used in the system. The office also expanded the system’s diversity, inclusion, and health literacy programs to include cultural competence and language access, and it initiated a program to empower the system’s employees to become involved in empowering communities. This led to the office decentralizing its activities and partnering with the system’s facilities-based experts to empower them, as Rosen explained, “to do right by their individual communities and the complex clinical needs in their areas, but also so they would feel that they were a part of something important.” Because the system encompasses so many different communities, programs were designed to use many different modalities to educate employees about relevant topics and in turn educate and involve their patients.

In 2013, the Office of Diversity, Inclusion, and Health Literacy became a division in the Office of Community and Public Health, which runs the system’s public health, community benefit, Community Benefit Excellence Council, and Katz Institute for Women’s Health activities. Rosen noted that a guiding principle of the Katz Institute is that all of its community initiatives, events, fact sheets, presentations, and other activities would all include the tenets of health literacy, cultural competence, and language access.

Rosen then discussed a few examples of the programs run out of the Office of Diversity, Inclusion, and Health Literacy. One program run in partnership with the Long Island Regional Adult Education Network includes a course called the ABCs of Health Literacy. This course trained the education network’s faculty to incorporate health literacy tenets into the classes taught at the network’s approximately 80 literacy sites on Long Island. In 2014, the office held a systemwide book drive that collected more than 4,000 books for literacy programs in the New York City area. Its public health initiative established a partnership with the underserved Spiney Hill community that established what Rosen called “traditional opportunities” to engage the community in health literacy and prevention strategies. Through this program, the office learned about cultural competence in a way that led to refocusing its efforts to involve the community in creating these initiatives.

The commitment of leadership to these types of activities is crucial, said Rosen, for without that commitment it is impossible to embed these

principles in the culture of the organization before demonstrating they produce a return on investment. At North Shore–LIJ, the system’s chief executive office and president chair an executive diversity, inclusion, and health literacy council, and the chief medical officer and chair of the department of medicine are cochairs of a physician leadership group. The system’s language access activities are now overseen by a systemwide committee, which coordinates activities conducted by the system’s 20 hospitals and its larger ambulatory practices that reach into their surrounding communities in a spoke-and-hub model. Rosen noted that these activities have recently won several innovation awards and recognition from various organizations dedicated to diversity and inclusion.

Rosen said that the system’s health literacy strategy has been able to expand thanks to New York State’s delivery system reform incentive payment (DSRIP) program that promotes community-level collaborations and focuses on sustainable system reform. In fact, North Shore–LIJ is leading the health literacy cultural, linguistic, and competency activities for the New York State DSRIP activities on Long Island. “We are proud of this, and it shows that our ability to bring initially siloed activities into one integrated program is going to have an impact on the communities that we serve,” said Rosen.

In her final comments, Rosen noted that North Shore–LIJ became the first large health system in the New York tristate area to take the American Hospital Association pledge to eliminate health disparities, even though this pledge includes what she called aggressive expectations and aggressive timelines. This pledge requires North Shore–LIJ to increase its collection and use of race, ethnicity, and language preference data, which Rosen said sounds simple but in fact is not. At Long Island Jewish Hospital, where she does most of her clinical work, 90 percent of the surrounding community’s population is listed as white and English-speaking, which she said is “dead wrong” given that the hospital serves the residents of Queens and their 175 languages. “So even with something that should be simple, there is an opportunity to do much better,” said Rosen.

Another requirement of the pledge is to increase cultural competency training, which North Shore–LIJ plans to accomplish with the same strategy it employed successfully in 2010 to address health literacy issues in the system. The third pledge is to increase diversity in leadership and governance, which system leaders have acknowledged is a critical feature of an equitable health system.

DISCUSSION

Ignatius Bau began the discussion by asking French if she knew of other examples, beyond Covered California and the New York State DSRIP

program, of opportunities to engage purchasers and providers in activities that align delivery system transformation with efforts that support culturally and linguistically appropriate services and health literacy. French said the marketplaces are great environments in which these activities can play out and that Medicaid will be an important innovator given that it serves diverse communities. CMS, which has the greatest clout, has begun efforts in this direction and has the opportunity to be a convener of a multipayer initiative. “Alignment and integration across payers is going to create the best opportunity for consistent, aligned efforts and common payment incentives with purchasers defining value in similar ways where measurement sets can also be aligned,” said French.

Bau then asked de Guia for ideas on how patients and consumers might engage in supporting community-based partnerships and how CPEHN is supporting integration activities in community-based and consumer-based organizations. De Guia replied that CPEHN began recruiting community-based organizations as early as 2007 when it realized that the voices at the policy table in California did not represent the diversity of the state’s population. She noted that The California Endowment and the California Wellness Foundation provided generous support enabling CPEHN to help its community-based partners build capacity to engage beyond the local level. CPEHN was also able to provide small grants to individuals to travel to Sacramento and testify to legislative committees. She reminded the workshop of the important role that individual stories play in changing hearts and minds and said, “Being able to bring individuals to Sacramento to talk about what the direct impact of policy actions would be in California has been a model that continues to work.”

Today, in the context of health care system transformation efforts, there is an important emphasis on engaging community and stakeholders, she continued. “The basic idea is we need to hear from the population itself and that proxies can provide one perspective but not necessarily the right perspective,” de Guia said. Going forward, it will continue to be important to ensure that community members have capacity and resources to continue to participate in transformation efforts, and doing so will require strong leadership and governance, as Rosen noted, and for programs to be transparent with regard to how consumers can participate.

Chin, in his presentation, mentioned the need to pay special attention to the role safety net providers play. Bau asked him to say more about addressing the additional burdens that safety net providers and community health centers might have to integrating health literacy, cultural competence, and language access services. Chin replied that despite the ACA, the system still creates more challenges for safety net providers in terms of having the most challenging patients, in terms of morbidity and socioeconomic and cultural challenges, and with respect to limited resources. “We have to

make sure they have the resources to do their mission, and also to create incentives in systems that do not make things worse,” said Chin. Doing so will require thinking specifically about policies and resource allocations that will maximize the chances that these safety net providers and community health centers will “make good things happen” in the populations they serve.

Bau then asked Rosen if she could say more about what has motivated the leaders of North Shore–LIJ to so strongly support transformative integration efforts. Rosen replied she believes it is a combination of “doing things right and doing things smart.” The doing right part comes from the system’s President and Chief Executive Officer, Michael Dowling, an immigrant and social worker by background. “But I also think he and our leadership team, both clinical and administrative, see that the business case to do this is critical and that jumping across the chasm too late will put us in financial jeopardy,” added Rosen. She believes that the timing for supporting these integration initiatives, which do not have an easy and early return on investment, has been brilliant.

Upon opening the discussion to the workshop participants, an unidentified participant asked how health literacy is assessed and if a patient assessed for health literacy skills is a health-literate patient. French replied the NCQA standard for its patient-centered medical home program is for the practice to systematically assess the health literacy of its patients and not to be prescriptive about how the practice does that assessment. Clearly, though, an assessed patient is not necessarily a health literate patient, she said. “What we are asking the practices to do is understand their literacy capacity and then to appropriately tailor their communications to the patient.” She noted, though, that if practices apply something akin to universal precautions—use plain language at low reading level for all patients—they do not have to do the specific patient assessments.

Ernestine Willis from the Medical College of Wisconsin asked the panelists to comment on her belief that while it is certainly possible to engage, motivate, and educate a community, to provide it with resources, and to build its capacity to engage, she is not sure that it is possible to empower a community because that has a paternalistic implication. Responding first, de Guia said she agreed absolutely with Willis and is conscious about not using the term empowerment. It is not her organization’s role to empower, she added, and she believes that the organizations CPEHN works with have the same attitude. “Our role is about education and awareness,” said de Guia. She said that she even hesitates to talk about capacity building. “Everyone has capacity. It’s more about sharing knowledge,” she added.

In working with many community groups on implementing the ACA, she has found that the health care system’s culture of coverage is confus-

ing and fragmented to many individuals and organizations. For those who do not speak English well or who are new to this country, it can be nearly impossible to understand copayments and deductibles or to choose between multiple different health plans and access coverage. As a result, CPEHN sees itself as an educator and information conduit, both to the community-based organizations and also to government agencies, policy makers, and research partners to make sure they understand the obstacles individuals face and why they need to have consumers at the table.

Chin agreed that information is important, but that it is not enough. “We also have to work on the self-efficacy piece so people feel more confident acting on that information,” said Chin. He used diabetes as an example, where proper self-management can address the great majority of potential health problems. Chin wondered if there really is agreement on this issue of empowerment and whether there is just confusion about the exact words. Rosen said she thinks of empowerment in terms of sharing knowledge and providing both access and insights as opposed to the top-down paternalistic meaning that Willis implied in her question. When she uses the word empowerment, she sees it as a way of leveling what was a particularly patriarchal process in years past, of changing a system that is not particularly good at producing good patient health outcomes. As an example, she said she empowers her obstetrician–gynecology partners by providing them with data that enables them to better care for their hypertensive pregnant patients, improving the end result for the patient.

Another unidentified participant identified an issue related to the use of the EHR, that is how physicians often face their computer screens more than they face the patient in the exam room. Rosen responded by acknowledging the problem and said that much of the patient education material embedded in the EHR is difficult to find and often inaccurate and ineffective. North Shore–LIJ’s Office of Community and Public Health has developed its own set of patient education materials, in partnership with various organizations such as the American Heart Association and WomenHeart, that are acceptably well written and health literate. Chin noted that someone at his institution has developed a method of teaching patient-centered care using the EHR that includes forming a triangle with the patient so the physician and patient can look at the screen together, asking questions that use data on the screen, and not looking at the screen when talking about a sensitive issue or mental health issue, for example.

This page intentionally left blank.