3

Linking Performance and Investments in Health

As companies adapt to the changing global economy and reach new markets, compete to attract talent, increase productivity, and operate in communities facing specific health challenges, investing in health can become a critical factor, and the opportunity exists to remain or increase competitiveness across the domains of their core goods and services, employee health, and community–employer interactions. Five panelists presented evidence and opportunities for how companies can improve their performance through investments in health. Specifically, Rebecca Weintraub focused on value generation in global public health; Frederic Sicre presented on socially responsible investing; Ray Fabius addressed the benefits of workplace health programs; Ron Goetzel discussed the common themes in workplace health programs; and David Wofford addressed both workplace and community health. Key messages from their presentations are included in Box 3-1.

GENERATING VALUE: STRATEGIC CHOICES FOR THE HEALTH CARE INDUSTRY

Rebecca Weintraub, Harvard University

Rebecca Weintraub, Assistant Professor at Harvard Medical School and Faculty Director of the Global Health Delivery Project at Harvard University, said that companies have identified opportunities to generate value in global health through strategic choices in redefining productiv-

ity in the value chain, redesigning of products and markets, and building supportive industry clusters. To illuminate the opportunities within these areas of value generation, Weintraub summarized four cases: Botanical Extracts Ltd.’s investments in local economies in the supply chain for artemisinin-based combination therapy; Olyset’s development of long-lasting insecticide nets; Wolters Kluwers’s UptoDate software; and CVS Health’s shift from selling products to improving health outcomes. Two of the case studies1—Botanical Extracts Ltd. and Olyset—are completed case studies published by Harvard Business Publishing and Harvard University’s Global Health Delivery Project. Weintraub noted that there are both prevention value chains and care delivery value chains embedded within shared delivery infrastructure.

Botanical Extracts Ltd. and Artemisinin-Based Combination Therapy

This case provides an example of redefining productivity in the value chain, tracing the establishment of Botanical Extracts Ltd. (BE)

__________________

1 For more information, see http://www.ghdonline.org/cases (accessed June 13, 2016).

as a manufacturer of artemisinin, the active pharmaceutical ingredient in artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) for malaria in East Africa. It details the founding of BE, its role in the ACT industry, and the complex supply chain for ACTs from the cultivation of the raw material to the delivery of ACTs as well as the public–private partnership (PPP) that was driving the manufacturing and delivery of ACTs.

Malaria disproportionately affects low- and middle-income countries, particularly sub-Saharan Africa. By 1990, every country in sub-Saharan Africa had reported chloroquine and other antimalarial resistance. Weintraub noted that the emergence of resistance to inexpensive treatments led to the development of ACTs. She explained that the innovation process dates back to 168 BCE, when it was realized that the plant Artemisia annua was being used in China to treat fever. Artemisinin combination therapy was then sold in the private-sector market as Riamet® in the United States and in the European markets as Coartem®. With the increasing awareness of the effectiveness of ACTs, Novartis entered into an agreement with the World Health Organization (WHO) to add Coartem® to WHO’s Essential Medicines List. The forecasted surge in demand led to the increase in the market price, incentivizing farmers and extractors to increase production.

Weintraub continued that the second part of the value generation was redefining productivity in the value chain through the production of an antimalarial with Artemisia plant sourced from local farmers. In 1994, BE explored the cultivation of the Artemisia plant by bringing together a group of farmers from Tanzania. The perceived global scarcity in artemisinin and increase in price motivated BE to scale up production by establishing facilities in other East African countries.

Novartis, which sourced its artemisinin exclusively from China, wanted to diversify artemisinin extraction to other regions of the world to both mitigate risk and cut costs. Novartis signed a preliminary supply agreement with BE for artemisinin production and supported the development of other facilities to meet the anticipated higher volumes. During BE’s scale up of production, several challenges such as the ability to extract enough artemisinin from the plant, demand shortfalls, heavy financial burdens, and unnerved farmers, led to a mismatch between demand and supply. Weintraub explained that, to sustain the business model and scale up process, Novartis absorbed the majority of these losses and maintained its commitment to the Coartem® program and BE.

A to Z Textile Mills Ltd. and Olyset Long-Lasting Insecticide Nets

This case highlights value generation through the redesign of products and markets by tailoring products to meet local market conditions

and building local capacity for health commodity manufacturing. It focuses on the establishment of the Olyset® Consortium, a PPP that was created to facilitate the manufacture of long-lasting insecticidal bed nets to prevent malaria infection in sub-Saharan Africa, and A to Z Textile Mills (“A to Z”), the manufacturer of the nets in Tanzania. Weintraub described how the PPP was developed, its use of an incentive-based supply chain, A to Z’s business model and impact, and the sustainability of the venture.

Weintraub explained that Sumitomo Chemical, a Japanese chemical company, developed the Olyset® bed net, a type of long-lasting insecticidal bed net (LLIN) developed to overcome the problems of low retreatment rates, washing, and erratic dose of the insecticide resulting in the shortcomings of the conventional insecticide-treated nets that were used to reduce the burden of malaria in sub-Saharan Africa. By 2002, a PPP of five for-profit and not-for-profit organizations met to prove the basic principles of technology transfer and local capacity-building as they apply to malaria prevention interventions; enable a sustainable, local supply of LLINs; and improve protection of vulnerable populations. Around this time, A to Z in Tanzania, which began as a children’s clothing manufacturer with five sewing machines operated by family members, was producing polyester mosquito nets. While A to Z grew because of its commitment to pursuing bed net manufacturing and sales, it diversified its bed net production to include insecticide treatment. Sumitomo Chemical chose A to Z as its LLIN partner and as part of its corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities, provided a royalty-free technology license to A to Z. Weintraub explained that the production of LLINs in Tanzania helped malaria reduction and also increased manufacturing capacity.

Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM), UpToDate, Wolters Kluwer

This case provides an example of strengthening health care systems to enable delivery. In the U.S. health care market, most physicians consult evidence-based sources to inform their decisions at the point of care. Weintraub said that nearly 90 percent of academic medical centers in the United States rely on UpToDate, an evidence-based electronic clinical information resource designed to provide clinicians with practical and reliable answers to clinical questions at the point of care. Sixty research studies confirm the widespread use of UpToDate, and its association with improved patient care and hospital performance, including reduced length of stay, adverse complications, and mortality, she added.

Weintraub noted that in October 2008 Wolters Kluwer, a global company that provides information, software, and services to legal, business, tax, accounting, finance, audit, risk, compliance, and health care professionals, acquired UpToDate. She explained that the combination of

UpToDate and Wolters Kluwer provided the market with an opportunity for advancing patient care while reducing medical costs. Strengthening the competitive context in key regions where the company operates in ways that contribute to the company’s growth and productivity. For example, in 2014 UpToDate saw robust growth as it completed its global launch of the UpToDate Anywhere mobile access platform and introduced its 22nd medical specialty, Palliative Care. The product is now used by more than 1 million clinicians in more than 170 countries. Weintraub concluded that not only does the software provide EBM, but the usage pattern data could possibly be used to project pandemics.

CVS Health’s Smoking Cessation Initiatives

This case examines redefining productivity in the value chain by adapting sales and distribution to penetrate new markets and better meet patient needs. In February 2014 CVS announced that it would stop selling cigarettes and tobacco products in its stores by October of that year to help people lead tobacco-free lives Weintraub noted that CVS Health’s bold anti-smoking stance earned the company praise from health advocates, and led to a rise in its stocks as well as increased sales—in spite of the loss of revenue from tobacco sales. She explained that despite sacrificing $2 billion in tobacco sales, CVS Health enjoyed a 5.5 percent year-over-year bump in same-store sales and a 22 percent increase in pharmacy services revenue in the months following its stop of tobacco sales and public rebranding as a health-focused company. Weintraub concluded that CVS has doubled its monthly smoking cessation visits, has increased its investment in mini-clinics, and is implementing the new enterprise brand across all its business units.

CORE BUSINESS PRODUCTS AND SERVICES

Frederic Sicre, The Abraaj Group

Frederic Sicre, Partner at Abraaj Capital, presented opportunities for investments in health in emerging markets, also referred to as global growth markets. Abraaj, a for-profit private equity investor, has been operating for about 14 years in 25 offices across the world with about 300 employees and $9 billion of assets under management. The organization invests in cities, seeing opportunities presented by the increasing urbanization rate, young demographic trends, rising middle class, and consumers that offer business opportunities. Shared value is at the center of Abraaj’s investment process, which includes a strong focus on environmental, social, and governance principles. “This is not just a ticking the

box kind of exercise, but using the lenses of environmental, social, and governance practice to see how they can either create new markets, new sources of revenue, or create long-term sustainable value in the enterprises in which they are investing,” he noted.

Sicre explained that Abraaj has deployed about $1 billion in the health care sector over the past 12 to 13 years. Health care expenditure in the growth markets has been increasing by 6.5 times over the past 12 years as compared to 2.5 times in the developed world, even projected against a growth in gross domestic product (GDP) per-capita increase. Urbanization and the rise in noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) are impacting this increase in expenditures. While efforts have been made in the past 10 years to lift millions of people in these emerging markets out of poverty, as a result, many of them are now subjected to NCDs associated with new lifestyles changes. Sicre noted that the lack of affordable, high-quality health care services in some of these emerging markets is pushing populations lifted out of poverty back into it.

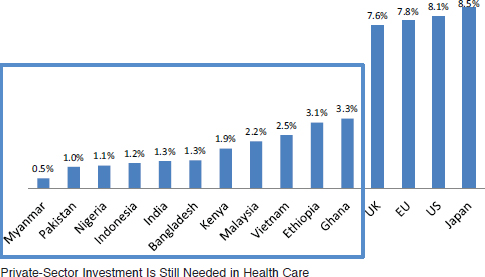

There are potential financial losses resulting from NCDs globally, thus providing a reason for the private sector to play a role in increasing access to quality and affordable care, Sicre explained. Government expenditure in health care in these markets is minimal (see Figure 3-1), creating a need he suggested for all sectors, including the private sector, to fund this gap.

Sicre cited an example of how the private sector could partner with the Nigerian government in training and providing education infrastructure for doctors to reach OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) levels by the year 2030, and emphasized that governments are listening and want to partner with the private sector to try and address these issues. In another example, he indicated that through private-sector initiatives in India, 75 percent of new beds have been put in hospitals. Sicre observed that moving forward in these PPPs allows for an alignment of government objectives with private-sector opportunities. He also noted the importance of nongovernmental organizations in these partnerships because of their local knowledge and on-the-ground delivery capabilities, an aspect that Mark Kramer from FSG mentioned earlier.

Sicre supports blended finance approaches that pool together public and private resources to solve large societal issues such as health care. However, he also emphasized that these approaches are not just about finance, but about the blended expertise, which is often overlooked. He pointed to some of Abraaj’s undertakings in India, the Philippines, and Pakistan. In these countries, Abraaj has seen the possibility of increasing efficiencies, sustainability, delivery, and also affordability, which is a key thing in terms of health care access in these markets. In one innovative example, The Abraaj Group has raised funds to bring together a private equity firm, The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the International

NOTE: EU = European Union; UK = United Kingdom; US = United States of America.

SOURCE: As presented by Frederic Sicre on December 3, 2015.

Finance Corporation (IFC), and the multinational company Phillips to address health care access in 10 cities in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. The idea for this investment process is not only to purchase several hospitals, then operate, grow, and scale them, but largely to fill the identified gap in the health needs for these cities. This investment hopes to address a range of issues from diagnostics to training of nurses, to building and making sure that procurement costs on equipment are lowered by having an approach that has 10 cities at stake, and use a “hub-and-spoke” model and training programs for community workers to try to address rural communities with limited health care access.

Sicre emphasized that business can play a huge role in addressing global health challenges and, more broadly, the Sustainable Development Goals. He closed by mentioning that Abraaj has been evaluating how to measure the social impacts of its initiatives, recognizing it as the key to sustainability. Abraaj has created an impact committee for health care investments to identify the metrics that can be used to measure affordability, accessibility, and quality of health care in the emerging markets where they are investing.

BENEFITS OF WORKPLACE HEALTH PROGRAMS

Ray Fabius, HealthNEXT

Presenting on the value of investing in wellness, and why population health and building cultures of health should be a corporate strategy, Ray Fabius, Co-Founder and President at HealthNEXT, framed his presentation on the following benefits of investing in wellness:

- Medical cost reductions

- Productivity gains

- Increased employee engagement

- Employer-of-choice enhancement

- Return to investors

In a study to evaluate the effect of its worksite health promotion program on employees’ health risks and health care costs for the period 2002 to 2008 at Johnson & Johnson, Henke and colleagues (2011) found that Johnson & Johnson experienced average annual growth in total medical spending that was 3.7 percentage points lower when measured against similar large companies. The company employees benefited from meaningful reductions in rates of obesity, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, tobacco use, physical inactivity, and poor nutrition. Average annual per-employee savings were $565 in 2009 dollars, producing a return on investment equal to a range of $1.88–$3.92 saved for every dollar spent on the program (Henke et al., 2011).

In a study to determine the ability of the Health Enhancement Research Organization (HERO) Scorecard to predict changes in health care expenditures, Goetzel et al. (2014) linked individual employee health care insurance claims data for 33 organizations completing the HERO Scorecard from 2009 to 2011 to employer responses to the Scorecard. Organizations were dichotomized into “high” versus “low” scoring groups and health care cost trends were compared. A secondary analysis examined the tool’s ability to predict health risk trends. Goetzel and colleagues found that “high” HERO scoring companies experienced better health care cost trends compared with “low” HERO scoring companies. After studying these benchmark companies, HealthNEXT identified 218 elements in 10 categories, and can now go into any company and score them out of 1,000 points, identifying their gaps from the benchmark and helping them to build a culture of health by scoring around 700, which is what the benchmark companies appear to score. In their recent study to evaluate the stock performance of publicly traded companies that received the highest best practice index scores on the HERO Scorecard in comparison against aver-

age market performance, as represented by the Standard and Poor’s (S&P) 500 Index, Grossmeier et al. (2016) found that stock values for a portfolio of companies that received high scores in a corporate health and wellness self-assessment appreciated by 235 percent compared with the S&P 500 Index appreciation of 159 percent over a 6-year simulation period.

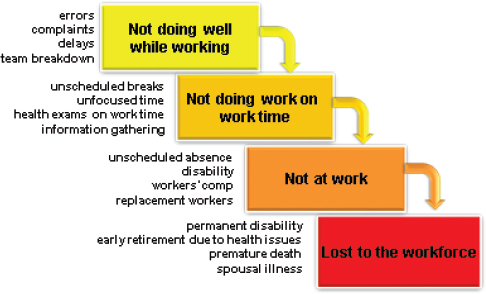

On the issue of productivity gain, Fabius noted it is evident that a skilled and willing workforce that is not well cannot create a competitive advantage. He added that poor health impacts safety, services, and financials, as depicted in Figure 3-2. In a study to explore methodological refinements in measuring health-related lost productivity and to assess the business implications of a full-cost approach to managing health, Loeppke et al. (2009) found that health-related productivity costs are significantly greater than medical and pharmacy costs alone (on average 2.3 to 1). The authors concluded that there is a strong link between health and productivity. He emphasized that employers who focus only on health care costs do not realize the true impact of poor health. Sherman and Lynch (2014) found a direct correlation between the cost of health care per worker at a manufacturing location and the degree of waste that that location engendered.

On the issue of employee engagement, Fabius noted that employee engagement functions two ways—doctors often talk about engagement as patients who are engaged in their health, and corporation leaders talk

SOURCE: As presented by Ray Fabius on December 3, 2015.

about engagement in terms of how loyal and how much discretionary effort an employee engages in, but in his opinion, employee engagement is squared. That is, as the health of workers is invested in, they take better care of themselves and they are more engaged in their work. Individuals are more likely to be higher performers, as demonstrated by findings from the Unilever LampLighter Program.

By engaging in a culture of health, a company’s employer-of-choice status is enhanced. This makes it easier for such companies to fill positions particularly in the global marketplace, and also reduces turnover remarkably relative to their industry peers. A Towers Watson report showed that companies with effective health and productivity programs achieved significantly better financial outcomes relative to their industry peers (Towers Watson, 2010). Also, a study to test the hypothesis that comprehensive efforts to reduce a workforce’s health and safety risks can be associated with a company’s stock market performance concluded that “companies that build a culture of health by focusing on the well-being and safety of their workforce yield greater value for their investors” (Fabius et al., 2013).

Ending his presentation, he called for the need to translate this information to the investment community. He noted that it is important for the investment community to know about the health and illness burden of the workforce in which they invest and supported efforts to develop health metrics as part of sustainability reporting.

COMMON THEMES UNDERPINNING WORKPLACE HEALTH PROMOTION PROGRAMS

Ron Goetzel, Johns Hopkins University and Truven Health Analytics

Setting the stage for his presentation, Ron Goetzel, Senior Scientist at Johns Hopkins University and Vice President of Consulting and Applied Research at Truven Health Analytics, referenced a study that supports prior and ongoing research demonstrating the business value of employing exemplary workplace health promotion and health protection programs (Goetzel et al., 2016). In this study, the authors examined the stock performance of 26 companies that won the C. Everett Koop National Health Award (www.thehealthproject.com) for the period of 2001–2014. Researchers compared the stock price for these companies to the S&P’s 500 index and found that companies recognized for their exemplary health promotion and safety programs outperformed the stock market as a whole by about 2 to 1.

In Goetzel’s opinion, companies’ shared accountability and shared value starts by showing they care about the health and well-being of their

workers. He noted that much of his research that examined the health and well-being of workers also spilled over into positive economic outcomes. While some workplace health promotion programs do not work, and may in some cases cause more harm than good, others do work, and work remarkably well. For example, programs in place for many years like the winners of the Koop Award have many of the elements necessary for success, and they also collect data documenting improved population health and cost saving. In a systematic review of workplace wellness programs led by Robin Soler at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the authors examined 86 studies of workplace health promotion that evaluated the impact of these programs on behavioral and biometric risk factors, health care use, and workers’ productivity. The review concluded there was sufficient or strong evidence that programs designed and implemented using evidence-based practices can exert positive impacts on outcomes important to businesses (Soler et al., 2010). Some recent case studies of effective programs included large companies like Johnson & Johnson, United Services Automobile Association (USAA), Dell Computer, and Citibank along with some small businesses, including Turck, Lincoln Industries, and Next Jump, an e-commerce company based in New York with 200 employees and $2 billion in annual revenues.

Goetzel noted that over the past 2 years, he and his colleagues have spent time visiting best and promising practice companies and disseminating information about their success ingredients through various social media vehicles supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Transamerica Center for Health Studies, American Heart Association, and the CDC. He alluded to the following 10 practices as the secret sauce that makes those companies successful:

- Creating a Culture of Health That Is More Than Just a Wellness Program, But a Way of Life. This is how the organization sees itself and communicates to its workers and to the outside world. It is ingrained in every aspect of the organization: its mission statement, its built environment, performance metrics, programs, policies, and health benefits.

- Leadership Commitment That Is CEO Driven. CEO commitment that is disseminated and communicated by middle managers, supervisors, and the people who give permission to lead a healthy lifestyle. A budget, business plan, annual report, and empowerment of workers and unions make workers feel like they are and become a part of the solution.

- Setting Specific Goals and Expectations. Goetzel proposed that setting short- and long-term objectives is essential, referencing a quote from Johnson & Johnson: “Think big, start small, act fast—

-

one step at a time.” A great deal of accountability needs to be in place so leaders and employees are responsible for doing their part to support a culture of health.

- Strategic Communication. Companies’ environs are surrounded by messages to be healthy and facilitators for a healthy lifestyle. Goetzel stated that those messages need to be consistent, constant, engaging, and targeted; and he suggested that it is essential to have a two-way communication dialogue so that employees have a chance to get back to the people who are designing these programs, and importantly to have “wellness champions” within the workforce who are committed to and supportive of health promotion, acting as local ambassadors for health improvement programs.

- Employee Engagement in Program Design/Implementation. Understanding what employees want is important, Goetzel noted. Employers use feedback from wellness committees, surveys, and focus groups to custom and tailor programs to meet employee needs. This helps employees assume ownership of the programs.

- Applying Evidence-Based Programs. Researchers studying behavior change and organizational change for many years have found that to change behavior, systems and scientifically based practices need to be put in place. Goetzel suggested individuals have to be given many choices in terms of things that are important to them, making the healthy choice the easy choice, and applying behavioral change theory/practice. He emphasized that healthy choices should be free from barriers, making them as convenient as possible.

- Effective Screening and Triage. In his opinion, providing annual online health risk assessments and follow-up interventions are essential. As for biometric screenings, Goetzel states these should comply with guidelines put forth by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (Behling et al., 2013). The provision of onsite clinics and counselors is also helpful.

- Offering Smart Incentives. Although it is an area of controversy, Goetzel suggests that tailoring, and providing alternative paths to motivate, reward, and help employees achieve their goals is essential. Incentive programs should be tiered so that employees get rewarded at each stage of health improvement. Some of the most successful incentive programs like lunch with the CEO are non-monetary and yet very motivating. These programs, Goetzel suggested, need to be voluntary so huge dollar amounts are not

- Effective Implementation. For implementation to be effective, Goetzel suggested it should be tailored to the company’s culture, and flexible, with integrated solutions. He added that the program should be fun and focus on achieving a healthy energized lifestyle, not on preventing morbidity and mortality.

- Measurement and Evaluation. In Goetzel’s opinion, this is a common denominator to all successful programs. It starts by getting all the significant people in the organization around the table and asking what they see as the most important accomplishments for the program and ways to measure those accomplishments. The diverse opinions from key stakeholders and employees can help management to better define program goals and the metrics associated with those outcomes.

associated with participation or achieving biometric outcomes. Goetzel stated that EEOC guidelines should be followed when setting up incentive programs.

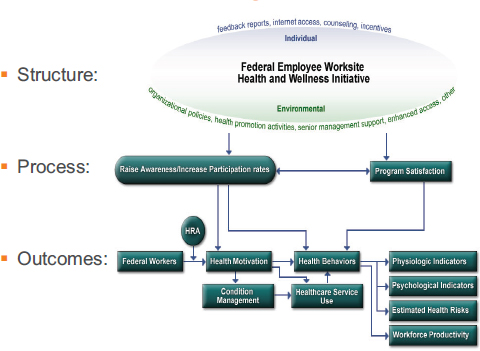

With a logic model on worksite health promotion that was developed by the CDC (see Figure 3-3), Goetzel highlighted the importance of measuring the structure of the program and its interventions that are focused both on an individual and on the organization. The program as a whole is assessed by using a structural analysis to determine whether the key components of the program are in place. The way in which the program is being delivered (its process) and the different set of outcomes need to be aligned.

He noted that workplace health promotion programs can work if they are done right and if they follow the best practices to which he alluded. He emphasized that workplace health promotion programs can lead to the following:

- Positive financial outcomes internally as well as externally: in terms of reduced medical cost, absenteeism, short-term disability, workers’ comp, safety, and “presenteeism,” which is on-the-job engagement.

- Positive health outcomes: adherence to evidence-based medicine, achieving behavior change, risk reduction, and health improvement at the population level, not just at the patient level.

- Humanistic outcomes: improvement in the quality of life of workers, their productivity, attraction and retention of talent, employee engagement, aligning with corporate social responsibility, having a balanced score card, and shared values.

NOTE: HRA = Health Risk Assessment.

SOURCES: As presented by Ron Goetzel on December 3, 2015; adapted from Soler et al., 2010.

ADDRESSING BOTH WORKPLACE AND COMMUNITY HEALTH

David Wofford, Meridian Group International, Inc.

David Wofford, Vice President for Public−Private Partnerships at Meridian Group International, presented a business case for health investments by multinational companies in their supply chains in low- and middle-income countries. He began by arguing that a new way of thinking about worker and workplace health beyond the traditional approach of occupational health and safety is essential. It is one that recognizes and emphasizes the unique needs of women, including their family planning needs. In his opinion, business has a role to play in expanding access to health services with stronger health systems in these countries. The world is fundamentally different than it was 50 years ago, and work has been reshaped everywhere due to globalization of the economy. Women make up an increasing part of the workforce in developing countries. Many are women of reproductive age who leave rural areas to work in urban

factories and agribusiness farms. They are disconnected from their social networks and public and private support systems. The old view that the main health responsibility of factories, farms, businesses, and other workplaces is to keep people safe from injuries and workplace disease, fails to adjust to these new realities in which women workers lack access to essential services.

Wofford suggested that many managers in these countries are unaware of the health needs and challenges of women workers, including the way their reproductive health impacts productivity; their lack of access to health services because of their sex; and the different needs they have for hygiene in the workplace. He mentioned that a recent McKinsey Global Institute report calls women’s access to health care and essential services an enabler of economic opportunity (MGI, 2015). Wofford noted that only a couple of corporate initiatives on women’s empowerment around the world make health, much less women’s health, a core component of those initiatives. In effect millions of women at the bottom of the economic pyramid who struggle to control their family size while seeking and maintaining basic employment are left out. He alluded to the strange divide in community and work as the cause of this disparity. He argued that the way global health and many others see workplaces as separate from the community highlights the fundamental divide in thought and practice, and this divide in some ways harms workers’ health, female workers’ health, and broader efforts to strengthen community and public health systems. He emphasized that business, whether formal or informal, is often the heart of communities and work is where people spend most of their time.

At the global level this divide is seen between the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the World Health Organization (WHO). Wofford noted that health is not a core labor standard under ILO conventions that govern workplaces. Also at the national level, ministries of health oversee all health professionals and health facilities, except at the workplace, which is the purview of ministries of labor. This fact leads to workplace health standards focusing on inputs, such as the number of nurses, or the availability of the number of fire extinguishers and exits, rather than the quality and availability of care for workers. It should not be surprising that many workplace infirmaries do not follow basic public health practices and protocols for hand washing, handling of hazardous materials, having Sharps containers, or confidentiality, but this is required of the public health or private health clinics outside the gates of those factories, he added. Building on his argument, Wofford mentioned that although WHO estimates that health providers in industry may comprise a surprisingly large percentage of the health workforce in developing countries, no one knows the real numbers because the data for an accurate

estimate are not easy to determine. He cited the listing of health staff at workplaces as industrial workers, not health care workers, as the reason for this data inaccuracy. The practical side of this divide is demonstrated in the fact that there is no good estimate of the number of doctors, nurses, and other providers hired by industry. “Imagine the shared value proposition to communities and business alike if there were better data on company health workers, better workplace services, and consequently better linkages between workplace health and public health systems when there are outbreaks for diseases like Ebola in the future,” Wofford said.

Wofford argued that companies are not just external partners, but rather core components of public health systems of the developing countries where they operate, in that they hire health care staff and send workers to the hospitals and clinics, often because of what happens in their workplace. Companies pay into government social security programs, sometimes health insurance funds, as well as other taxes, and they have a vested interest in the health of workers in their communities. He noted that a different paradigm also means that if business is to create shared value around health, it needs to think not just about what it does in the community in its investments, but also how it addresses health in its own operations because these actions and activities are interrelated and not separated. He noticed that the evidence of the benefits to business and communities of investment in health and women’s health is imperfect, often anecdotal, and qualitative, and not very experimental, but extremely strong.

Investing in health and women’s health at the macro level is important to a country’s economic growth (Bloom et al., 2004), demographic dividend (Bloom et al., 2003), and gender equity and women’s participation in the workforce. Wofford also pointed to evidence showing the benefit to companies and workers of better workplace policies, practices, and programs addressing workers’ and women’s health, as other presenters have discussed. He noted the positive impacts at the community level when women workers documented sharing health knowledge gained at the workplace with friends, sisters, children, and neighbors.

Wofford mentioned that although important, he disagrees with the assumption that generating stronger evidence on the business case is the key to spurring business investment in developing countries and in their supply chains. He argued that the problem is not simply about getting better evidence and indicators. For example, the ILO data, in its synthesis reports on garment factory monitoring in seven countries, showed that occupational safety is the leading area for noncompliance, suggesting according to Wofford that factory management does not see a business case for even basic levels of health compliance. Wofford suggested that the problem with the business case as it currently is formulated is that it

fails to address the core incentive structures at the workplace and within the global supply chains. He continued that demonstrating a range of direct and indirect benefits to owners and top managers of factories and farms is rarely enough. He noted that workplace managers see health as compliance; and worker health as a cost that is often a waste of time and resources. He mentioned that these managers do not get rewarded by owners or by corporate buyers of their products for having healthy workers in good health services. As a result they do not manage their health facilities or staff, or consider these as strategic resources that can support productivity and business operations.

Wofford observed that what is found in many factories and farms over the world is that health care staff are underused and undertrained and spend large parts of their time doing very little. For example, a key reason why factories in Haiti are not compliant with the number of nurses they are required to have onsite is because managers say “why should we hire more nurses, the ones we have aren’t doing enough.” He noted that this is not their fault because they could be doing much more with management direction and support. In an argument that Wofford and his team made to a factory in Haiti with a very progressive management, they advised the factory that in managing their health staff they needed to think of staff as a production resource. The management team agreed and a project was launched with three basic parts—transforming the role of nurses to make them proactive and focus on preventive care, instituting basic standards and protocols in the infirmary that they had, and integrating the health function into real management. Wofford explained that in addition to the business and health benefits, the health system-strengthening interventions in Haiti seemed to have indirect knock-on benefits that in some ways have little to do with health and have everything to do with business itself, including better management skills, better use of data, better processing, and effective problem-solving skills. He noted that it is difficult for management to recognize its health team as a strategic resource that is part of supporting productivity and business operations. In his opinion, this is why the business case is so essential for opening the door to new ways of thinking about worker health and worker programs. However, the business case alone is not sufficient to get many companies to walk through that door. Because business can play a vital role in efforts to strengthen systems and expand services, the growing number of women in the global workforce demands a rethink of workplace health policies and practices as traditional occupational health fails to address the impact of work on their reproductive and general health and the health of workers overall. He pointed to the Haiti project as one approach to bridging the work and community divide. Because workplaces do not work in a void, creating shared value in women’s health is

not just about what individual workplaces do, but the public and private incentive structures that affect business thinking and the decisions at all levels: global, national, company, and community.

“Supply chain companies respond to the priorities and policies of multinational companies that buy their products. They are also influenced by public policies on occupational health and safety. Business and global health need to tackle these policies at all levels. And it may seem daunting, but in fact the public health side deals with these levels all the time,” Wofford concluded.

PANEL DISCUSSION

When asked how improved workplace health policies and practices will help create shared value for the community and beyond the workplace, Wofford answered that although he believes that what happens in workplaces around health and behavior change is transmitted in the community both by people sharing information and changing values and health behaviors among others, more research is needed to see whether that is actually true. He added that factories and workplaces can make big differences in other ways. He cited an ongoing project in Cambodia as an example. He noted that one of the problems in Cambodia and other countries is that workers do not utilize high-quality health care service providers. One of the ways to change the policies and practices of workplaces is referring workers to quality providers. In doing so, behaviors are changed and a notion of going to a high-quality provider rather than just any provider is created. He added that another way of looking into the Cambodia project is to link government and public health processes for licensing, training, and registration of nurses to workplaces and the private sector. Fabius approached the question slightly differently, and explained that the overdependence on other services other than primary care by health workers makes the health care system not appropriately utilized. He suggested that the best place to start for health care delivery systems is with their own workforce.

When asked about how to measure long-term population health improvement when there are many different ways to define the problem and success in addressing it, Goetzel answered that the set of outcomes to be measured vary depending on the audience. In his opinion, there are three buckets of outcomes—financial outcomes, health outcomes, and humanistic outcomes. Out of these categories individuals can create standardized metrics, but the relevance of the standardized metrics to any given audience member will vary.

Weintraub suggested that new policy makers can be overwhelmed with the number of metrics through which initiatives can be evaluated.

One approach can be to simplify by honing in on one specific metric to single out important issues, and then look at the solutions. One example is the access a woman has if she is in obstructed labor. If one has access to a C-section, then what funnels down from there, for example, is one has a referral base, has transportation, and has had prenatal care, Weintraub explained.

Sicre explained that in a diagnostics laboratory investment that Abraaj made in Egypt, it continued to grow the company organically and also expanded it to other markets, even during the revolution. Some of the key buckets that they looked at in terms of metrics were financial, performance, and social performance factors, including how the company was expanded and scaled, how many additional facilities were rolled out, how the management of the company was improved, how managerial capacity was created, how many clinical staff were added, what operational improvements any private equity firm would make in any kind of company, and how the reach to the low- and middle-income classes of that given market was increased. Sicre agreed with Wofford that the company is the center of the community and such a position offers an opportunity for any kind of company or sector to have positive impacts inside and outside the workplace. Sicre added that companies do not need to be large companies with large resources to make those impacts. He mentioned that there are extraordinary new models that are emerging in these new markets and encouraged the United States to look at some of the models because not everything has to be a Western-based model.

When asked if the incredible demand for U.S.-like benefits in the emerging markets should be met, Fabius explained that maybe what is needed to set a goal is not necessarily flat health care cost, but at least the achievement of decreasing health burden over time. Goetzel agreed with Fabius and added that it is not the company that decides the health and well-being of the workforce, but ultimately it is the individual worker who says “this is something that’s going to benefit me and my family, something I’m going to adopt because it’s a good idea for me.” Goetzel suggested that different interventions and approaches need to be tested to see which ones work for the company and the workforce.

When asked if there is an opportunity to connect CSR efforts around supply chains to what’s happening for the multinational company, Fabius referenced a book by Sisodia and colleagues that highlights those companies that are loved by all of the constituents in their supply chain (Sisodia et al., 2014). These companies have broadened their horizons to be more than the sole seekers for profit maximization, existing for a higher meaning and responsibly serving the interests of all stakeholders. Their customers love them, their vendor partners love them, their shareholders love them, and Sisodia and colleagues label them as “firms of endear-

ment.” He added that when the investment of portfolios of these firms are studied, they remarkably outperform as well. Goetzel noted that CSR is one of many elements, but it is most likely one with high importance because it aligns with job satisfaction, which also has been shown to be a major predictor of company success. Wofford commented that he thinks there is a huge world where health and using financial markets and marketing can make a big difference in what happens in the supply chains, and health in companies and how it can affect communities.

A workshop participant pointed out that from the perspective of a corporation, it makes perfect sense to promote healthy lifestyles, preventive medicine, and population health, but that is in contrast to a large for-profit health care industry in the United States, and other fragments of the health care system, such as veterans’ health. How do consumers of healthcare understand these opposing cultures for best outcomes? Commenting on the impact that one might have on the other in terms of their success, Goetzel suggested that companies could be thought of as micro systems or macro systems. In his opinion, they have control over the workforce in terms of policies, programs, incentives, communication, and data which is the starting point for creating population health. Goetzel mentioned that the government will never try to provide health education and health promotion to the 155 million Americans going to work every day and spending most of their day at work. He emphasized that companies have a major role to play, and it is in their self-interest to invest in the health of their employees. Fabius agreed with Goetzel and added that looking at the determinants of health, the employer has many more levers to pull than a delivery system, an insurance company, even the family itself, because the employer has an opportunity to provide employment, a greater sense of purpose, an opportunity for advancement, income, a healthy environment, benefits that can provide incentives for a healthier opportunity, and access to health care onsite or nearby, just to name a few.