3 A Framework for a Learning Trauma Care System

The committee was asked to identify and describe the key components of a learning health system necessary to optimize care of individuals who have sustained traumatic injuries in military and civilian settings. In this chapter, the committee describes the characteristics of high-performing learning health systems and, by applying a learning system lens to trauma system components, develops a framework for an optimal learning trauma care system.

CHARACTERISTICS OF A LEARNING HEALTH SYSTEM

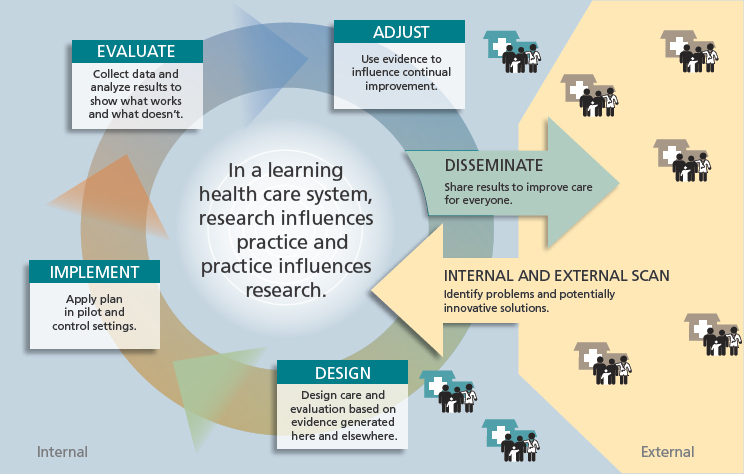

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) defines a continuously learning health system as one “in which science, informatics, incentives, and culture are aligned for continuous improvement and innovation, with best practices seamlessly embedded in the delivery process and new knowledge captured as an integral by-product of the delivery experience” (IOM, 2013, p. 136). In this inherently iterative process, innovation is introduced and continuously refined in response to evolving care needs and circumstances (see Figure 3-1). In the absence of a learning system approach, the diffusion of new evidence, innovation, and knowledge can take considerable time (Rogers, 2010). A learning health system holds great promise, offering a path by which the many stakeholders involved can manage health care’s rapidly increasing complexity; achieve greater value; and capture opportunities from emerging technology, industry, and policy (IOM, 2013). In short, a continuously learning health system aims to deliver the best care, optimizing outcomes for patients across the system at greater value.

SOURCE: From Greene et al., 2012. Copyright © 2012 American College of Physicians. All Rights Reserved. Reprinted with the permission of American College of Physicians, Inc.

In developing a framework for a learning trauma care system (described later in this chapter), the committee built upon the components of a continuously learning health system characterized in the 2013 IOM report Best Care at Lower Cost (see Table 3-1). These elements capture not only the technical and practical components required to improve care but also the system-level characteristics necessary to encourage continuous learning and improvement. These seven components, falling under the categories of science and informatics, patient–clinician partnerships, incentives, and continuous learning culture, are requisite in designing a health system characterized by continuous learning and innovation.

Although necessary, these seven structural components are by themselves insufficient to ensure the success of a learning health system; a sound strategy and system architecture are not a guarantee of effective implementation. Success depends also on the way in which these components align and work together to facilitate continuous learning and improvement. Inertia, conflicting values, oversaturation of ideas, and fear are all potential barriers that can stall and even dismantle the efforts of a system striving toward rapid continuous learning.

Across multiple sectors, there are exceptional examples of learning systems characterized by large-scale learning and exchange around a shared

TABLE 3-1 Components of a Continuously Learning Health System

| Science and Informatics | |

| Real-time access to knowledge | A learning health system continuously and reliably captures, curates, and delivers the best available evidence to guide, support, tailor, and improve clinical decision making and care safety and quality. |

| Digital capture of the care experience | A learning health system captures the care experience on digital platforms for real-time generation and application of knowledge for care improvement. |

| Patient–Clinician Partnerships | |

| Engaged, empowered patients | A learning health system is anchored on patient needs and perspectives and promotes the inclusion of patients, families, and other caregivers as vital members of the continuously learning care team. |

| Incentives | |

| Incentives aligned for value | A learning health system has incentives actively aligned to encourage continuous improvement, identify and reduce waste, and reward high-value care. |

| Full transparency | A learning health system systematically monitors the safety, quality, processes, prices, costs, and outcomes of care, and makes information available for care improvement and informed choices and decision making by clinicians, patients, and their families. |

| Continuous Learning Culture | |

| Leadership-instilled culture of learning | A learning health system is stewarded by leadership committed to a culture of teamwork, collaboration, and adaptability in support of continuous learning as a core aim. |

| Supportive system competencies | A learning health system constantly refines complex care operations and processes through ongoing team training and skill building, systems analysis and information development, and creation of the feedback loops for continuous learning and system improvement. |

SOURCE: Adapted from IOM, 2013, p. 138.

goal (see Boxes 3-1, 3-2, and 3-3). In drawing on these and other models, the committee identified attributes that distinguish exceptional, high-performing learning systems from typical systems (summarized in Table 3-2). These attributes described in the sections below, can be envisioned as animating the IOM report’s structural framework, highlighting various management approaches that will encourage a learning system to truly thrive.

TABLE 3-2 Characteristics That Distinguish Exceptional, High-Performing Learning Systems

| TYPICAL LEARNING SYSTEMS | EXCEPTIONAL LEARNING SYSTEMS |

| The aim of the network is to facilitate general learning. | The aim of the network is crisp and quantifiable. |

| The system is oriented to focus upward in the hierarchy; leadership receives data and reports. | The system is oriented to focus on the needs of the customer; leadership removes barriers to progress in the field. |

| The system catalogues explicit knowledge (libraries). | The system facilitates the exchange of tacit knowledge (just-in-time). |

| The system furnishes aggregate information. | The system measures team performance. |

| The system has “theory lock”. | The system applies many stimulants to effect change. |

| A large investment is made in teaching and training. | Experimentation and improvisation are encouraged; there are high expectations for testing and adjustment. |

| Consensus is regarded as a value. | Agility is regarded as a value. |

| New networks are created. | Existing networks are harnessed. |

| The system is centrally managed. | System management is distributed; losing control is viewed as success. |

SOURCE: This table draws on McCannon and Perla (2009).

Setting Crisp, Quantifiable Aims

In a typical learning system, there exists a vague notion that the aim for the system is to facilitate learning. This aim, however, does not create a sense of urgency around improving performance. Exceptional learning systems mobilize people to action by setting crisp, quantifiable aims that are oriented toward specific improved outcomes—for example, reducing clinically preventable mortality to zero.

Focusing on the Needs of the Customer

When a system is focused upward in the hierarchy and stakeholders are concerned primarily with using data and reports to placate leadership, the capacity of the system to learn is limited. Exceptional learning systems are oriented to focus on the needs of the customer (in a health care system, these would be the front-line providers of care), and leadership is focused on removing barriers to progress in the field. Project Extension for Commu-

nity Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO) is an example of a learning system that has excelled because it is driven by a strong customer focus (see Box 3-1).

Facilitating the Exchange of Tacit Knowledge

Knowledge can be categorized as either explicit or tacit (Polanyi, 1966). Explicit knowledge can be collected and transmitted in a formal and systematic way (Nonaka, 1994; Polanyi, 1966). Although didactic methods (lectures, reading textbooks) are predominant as an educational model, a preponderance of evidence shows that optimal learning in adults does

not occur through such methods; rather, knowledge is more efficiently absorbed and transmitted through practice and application. Tacit knowledge is contextual and draws on personal experience to include insights and intuitions that may be difficult to formalize and communicate to others (Becerra-Fernandez and Sabherwal, 2001). The classic example that conveys the difference between explicit and tacit knowledge is learning to ride a bike. Anyone who has ever ridden a bike can testify that one cannot learn to ride a bike from a set of directions, but must get on and learn through experience how to calibrate one’s balance.

A common tendency in a typical learning system is to catalog or make libraries of knowledge and information so as to capture everything that is known in one central location. However, vast databases of such explicit knowledge do not necessarily translate to improved performance at the periphery. An exceptional system is characterized by an understanding that much more useful to those responsible for delivering care in the field is access to expertise that yields practical or tacit knowledge of how care is best delivered, often thought of as “tricks of the trade.”

Measuring Team Performance

Continuous tracking and measurement of progress is requisite to accomplishing any goal. In high-performing learning systems, however, the generation of performance data extends down to the level of the team or individual practitioner. Like having clear and quantifiable aims, performance data that show progress at the provider level can generate excitement and inspire corrective action far better than aggregate data showing only system performance. Illustrating this point, a commitment to monthly reporting and measurement of each individual community’s progress against carefully determined benchmarks was crucial to the success of the 100,000 Homes Campaign, a learning network that housed more than 100,000 chronically homeless people over a 4-year period (see Box 3-2).

Applying Multiple Stimulants to Effect Change

Changing behavior is a complex and challenging undertaking requiring a multifaceted approach that encompasses both positive and negative stimulants (carrots and sticks). Too often, the full array of available incentives is neglected in favor of a single mechanism for driving engagement, a concept known as “theory lock.” In health care, for example, there is a strong focus on using payment as an incentive for changing the way care is delivered (IOM, 2013). Although certainly important, payment alone does not provide sufficient incentive to drive behavior change systematically. A more sophisticated approach is to apply multiple stimulants, focusing heav-

ily on positive reinforcement such as recognition and collaboration, but also including regulation and transparency, and in cases of negligence or serious underperformance, even disciplinary action.

Encouraging Experimentation and Improvisation

Strict adherence to what one has been taught leads to system stagnation. Continuous learning and associated improvements in care occur through experimentation in the field, and exceptional learning systems encourage (and even require) this kind of behavior. Although such tools as clinical practice guidelines are useful for disseminating best practices in health care and reducing unwarranted variations in practice, rote compliance with such protocols may also lead to harm since no guideline can perfectly fit the needs of every patient. However, empowering health care providers to deviate from protocol based on the best information at hand requires an environment free of fear.

Regarding Agility as a Value

Consensus, while an important value that has its place in a learning system, can have the undesirable effect of bogging the system down and impeding progress. The superior values are agility and speed. As long as there

is consensus on aims, allowing stakeholders to explore different approaches toward those shared aims can rapidly advance knowledge and learning.

Harnessing Existing Networks

All human systems are encoded in networks. People use a myriad of different structures and processes to connect with each other. Consequently, building new networks from scratch to solve any particular problem is inefficient. Exceptional learning networks harness and build on those that already exist.

Instituting Distributed System Management

The typical system is centrally managed; guidance and rules are dictated by a central organization. However, tight central management of the system can impede the rapid learning that can occur when front-line providers are encouraged to improvise and experiment (as discussed above). When peripheral participating organizations are empowered to run ahead of the center and function as laboratories for learning, not only are specific practices and knowledge being spread, but a culture of change management evolves within those organizations.

A FRAMEWORK FOR A LEARNING TRAUMA CARE SYSTEM

Systems for trauma care, like all other facets of health care delivery, face challenges in distilling an ever-expanding knowledge base from research and other scientific inquiry into meaningful clinical evidence and rapidly translating that evidence into wide-scale improvements in patient care. Too rarely is available knowledge used to improve the care experience. Equally inadequate is the extent to which information on the care experience is captured and applied to improving the knowledge base (IOM, 2013). The consequences include missed opportunities, waste, and preventable morbidity and mortality, as is evident in the variation in practice and outcomes observed in the field of trauma care (summarized in Chapter 2). This variation represents a failure in knowledge management and indicates that systems are not designed and managed to support optimal care and learning. A rapidly learning health system leverages recent advances in health information technology to access and apply evidence in real time, drawing knowledge from both traditional clinical research and patient care experiences. The combination of these forms of knowledge generation works to advance the rapid adoption of best care practices. In short, “evidence informs practice and practice informs evidence” (Greene et al., 2012, p. 207).

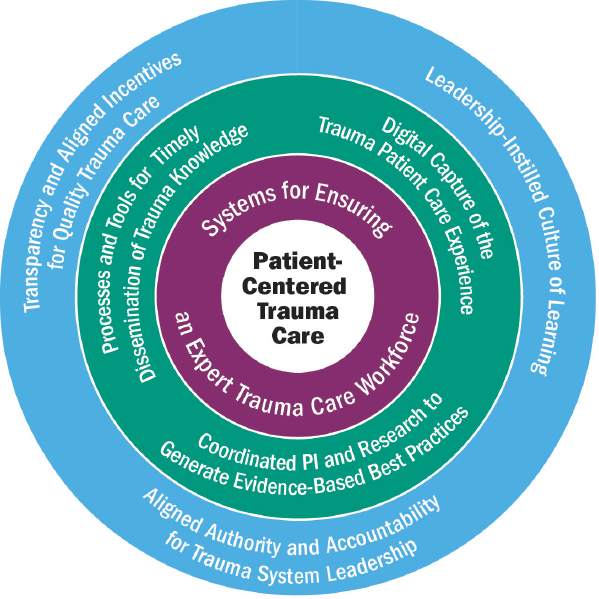

By applying a learning health system lens to the critical elements of a trauma system, the committee identified the following components of a continuously learning trauma care system optimally designed for continuous learning and improvement. These components are characterized in Table 3-3, which follows Figure 3-2, and detailed further in the following sections.

NOTE: PI = performance improvement.

Digital Capture of the Trauma Patient Care Experience

In a learning trauma care system, knowledge develops as a natural byproduct of care processes such that each patient experience yields information on the effectiveness, quality, and value of the trauma care delivered. To this end, patient care experiences across the continuum of care are digitally

TABLE 3-3 Components of a Continuously Learning Trauma Care System

| Digital Capture of the Trauma Patient Care Experience | Patient care experiences across the continuum of care are digitally captured and linked in information systems, including trauma registries, such that each patient experience yields information on the effectiveness, quality, and value of the trauma care delivered. Bottom-up design of data systems, where care generates the data, ensures that data capture is seamlessly integrated into the provider workflow and is available in real time for performance improvement primarily and research secondarily. |

| Coordinated Performance Improvement and Research to Generate Evidence-Based Best Trauma Care Practices | The supply of knowledge is continuously and reliably expanded and improved through the systematic capture and translation of information generated by coordinated performance improvement and research activities. |

| Processes and Tools for Timely Dissemination of Trauma Knowledge | Trauma care providers have access to tools such as continuously updated clinical practice guidelines and clinical decision support tools to capture, organize, and disseminate the best available information to guide decision making and reduce variation in care and outcomes. Clinical decision support tools and telemedicine make knowledge of best trauma care practices available at the point of care. |

| Systems for Ensuring an Expert Trauma Care Workforcea | Continuous learning and improvement are designed into trauma system processes. Ongoing individual skill building and team training, as well as feedback loops, build and sustain an expert trauma care workforce. |

| Patient-Centered Trauma Care | The trauma care process is managed around the patient experience, feedback is sought from trauma patients when the process is evaluated for improvement, and patients are involved in redesign of the trauma system and have a voice in trauma research. Patient-centered care features timely access to high-quality prehospital, definitive, and rehabilitative care, with seamless transitions between each of these echelons to ensure that physical and psychological health care needs are met. |

| Leadership-Instilled Culture of Learning | Leadership will influence the extent to which a culture of learning and improvement permeates a trauma system. Leadership instills a culture of learning by defining learning as a central priority of a trauma system, removing barriers to improving care systems and, most notably at the point of care, setting quantifiable aims against which progress can continually be measured and promoting a nonpunitive environment. |

| Transparency and Aligned Incentives for Quality Trauma Care | Drawing on data from trauma registries and other information systems, performance improvement programs support the evolution and improvement of trauma systems by benchmarking systems’ performance against that of other similar organizations and by making performance information available at the provider, team, center, and system levels. Multiple complementary incentives are aligned to encourage continuous improvement and reward high-quality care. |

| Aligned Authority and Accountability for Trauma System Leadership | Responsibility, authority, and resources are aligned to enable leadership to steward the system. Defined leadership is accountable for trauma capabilities and system performance, with the authority to create and enforce policy and ensure that the many stakeholders involved work together to provide seamless, quality care. |

a In an expert trauma care workforce, as defined by the committee, each interdisciplinary trauma team at all roles of care includes an expert for every discipline represented. These expert-level providers oversee the care provided by their team members, all of whom must be minimally proficient in trauma care (i.e., appropriately credentialed with current experience caring for trauma patients).

captured and linked in information systems, including trauma registries, to enable the generation, exchange, and application of information for the following purposes:

- Surveillance—Surveying the data in a registry can lead to the identification of trends in injury patterns, mortality, and long-term outcomes.

- Performance improvement—Registry data can be used to generate performance data at the individual provider, team, and system levels and inform changes in clinical practice or system design.

- Research—Significant challenges impede the conduct of prospective randomized controlled trials on trauma care in civilian and military settings. Registry data offer the opportunity to perform retrospective, hypothesis-driven, outcomes-based analyses to identify best practices or gaps in care.

If aim defines the system, the primary aim of a trauma management information system needs to be clinical improvement, with support for research serving as a secondary aim.

Trauma registries, which collect disease-specific clinical data in a uniform format, are an important tool for knowledge generation in a learning trauma care system. In such a system, data from hospital-based registries are collated into a regional registry that includes data from all hospitals

in the system and linked such that data generated across the continuum of care are available in a single data set. When possible, these data are further linked to law enforcement, crash incident reports, emergency department records, administrative discharge data, medical examiner records, vital statistics data, and cost data to provide epidemiologic and outcome information, as well as information related to cost-effectiveness. These data are made accessible by the lead agency to support injury surveillance, performance improvement efforts, and trauma care research. Data have the greatest impact if they conform to national standards1 related to case acquisition and registry coding conventions. Adhering to such standards increases the value of state trauma management information systems by providing national benchmarks and allows the lead agency to evaluate the performance of the entire system.

To support optimal learning, clinical quality of care, and continuous improvement, data systems (which capture the trauma data included in registries) are designed using a bottom-up approach so that data capture is seamlessly integrated into the provider workflow. Measurement for improvement purposes focuses on care delivery processes, as opposed to individual provider performance (Berwick et al., 2003). Bottom-up design captures data at the level of small, individual decisions, including both process steps and outcomes. Clinicians’ access to their own short- and long-term clinical results encourages individual improvement. Bottom-up design further supports the consolidation of these data across all clinicians to support assessment of care processes at the level of a clinic, hospital unit, hospital, health care system, state, or country (James and Savitz, 2011).

Through the collection of clinical, cost, and patient satisfaction data, bottom-up data systems improve care while reducing costs. This approach is more timely, efficient, and accurate than that used by top-down data systems, which measure for selection rather than improvement. Top-down systems focus on a number of readily available intermediate or final outcome measures, ranking individual providers with the intent that public reporting and consumers’ desire to select high-value care will incentivize providers to improve their own performance. Such system design, however, fails to capture the granular data necessary for improvement. Furthermore, selection measures are expensive to collect and frequently are inaccurate, incomplete, and untimely, given the necessity of relying on data abstraction (Berwick et al., 2003).

__________________

1 Two such national civilian standards are the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s National EMS Information System, which standardizes the collection of data on emergency medical services (Dawson, 2006; Mann et al., 2015), and the American College of Surgeons’ National Trauma Data Standard, which addresses the standardization of hospital registry data collection (ACS, 2015).

The granular data elements captured in bottom-up systems are a critical part of regular care delivery. With proper design, these elements can be integrated into routine care so that front-line providers see them as essential to their daily work rather than as an external burden. The following steps are entailed in the design of a bottom-up data system and its integration into clinical workflow to create an outcomes tracking system2:

- Identify a high-priority clinical process. Select processes at the decision level (i.e., the individual steps used by clinical teams to actually deliver care).

- Build an evidence-based clinical practice guideline for the target process,3,4 using formal evidence review, expert opinion, and existing acceptable practice. Represent the guideline as a flow chart that tracks at the level of clinical workflow—again at the decision level, where clinicians make choices and execute actual care. Usually, the best way to do this is to track a typical patient sequentially through the process.

- Lay out how the guideline might blend into the clinical workflow, using such tools as standing order sets, clinical flow sheets, action lists, and patient worksheets. Often these tools are integrated into an electronic medical record.

- Build a bottom-up data system5 into the same clinical workflow. This data system will track all variations from the guideline, as well as intermediate and final clinical, cost, and satisfaction outcomes

__________________

2 The outlined process adapts the formal methods used for designing data systems that support large, multicenter randomized controlled trials (Pocock, 1983).

3 This guideline does not need to be perfect; it just needs to come close enough to be integrated into clinical work.

4 Military and civilian trauma systems have developed and use numerous clinical practice guidelines. For these clinical processes, steps 1 and 2 are already complete.

5 Generally, the same team that developed the guideline also builds the data system.

- For each step in the guideline, identify reports and analyses useful for understanding and managing the care of individual patients and the process as a whole.

- Build a trial example of actual reports that the final outcomes tracking system should routinely produce.

- Identify all data elements necessary to build each report and build a formal coding manual.

- Reduce the coding manual to a self-coding data sheet.

- Test the self-data coding sheet against the final report packet and in actual clinical practice.

- Cross-walk the final coding manual against existing automated data, identifying missing data elements.

- Data architects design data storage structures within a data warehouse. Analysts prepare and program standard analytic reports for automated production (James, 2003).

-

(James, 2003; Nelson et al., 1996). These point-of-contact data can then be captured in a longitudinal registry.

- Establish a formal organizational structure (e.g., a clinical development and review team) that regularly reviews guideline variations and clinical outcomes, with the aim of systematically improving the guideline to better serve and support front-line teams. This group keeps track of salient new research findings in the peer-reviewed literature and incorporates proven innovations into the guideline. This same group usually leads internal “drill down” improvement efforts6 (James, 2003).

By incorporating a clinical practice guideline into providers’ routine workflow, bottom-up systems ensure that providers need not rely on their own memory. Furthermore, this process validates the guideline against actual practice; supports regular updating of the guideline to keep it aligned with best current practice; and provides transparency data to clinical teams, patients, and health care overseers. With rare exceptions, it is impossible to build a guideline that perfectly fits any patient. It is the professional duty of the physicians, nurses, pharmacists, therapists, and technicians who care for the patient to vary from protocol based on individual patient needs. In the event that variation is necessary, clinicians explain this as part of the clinical record. The ability of bottom-up data systems to identify and track outlier cases to their root causes also allows data system designers to identify and correct any errors within the data system itself (as opposed to variances in care decisions) that may be producing these outliers. This feature supports the continuous improvement of the data system, encouraging broad support and trust from front-line provisions. The result is a reduction in practice variation and continued improvement in care through the existence and operation of a continuous learning loop. An example of a civilian health system that has successfully utilized this bottom-up approach is described in Box 3-3.

Coordinated Performance Improvement and Research to Generate Evidence-Based Best Trauma Care Practices

A core aim of a learning health system is to expand and improve the supply of knowledge available to address health care questions. “The capacity for learning increases exponentially when the system can draw knowledge from multiple sources” (IOM, 2013, p. 164). Thus, a learning trauma care system derives evidence for best care practices from a combi-

__________________

6 “Drill down” performance efforts support investigation and improvement. Knowledgeable experts propose and test data elements that might be interesting. If suggested data elements demonstrate utility, they are then merged into the larger outcomes tracking system.

nation of traditional research methodologies and more nimble methods for generating knowledge from patient care experiences.

Fundamental to the concept of a rapidly learning health system is the use of patient data to generate clinical evidence through a continual process of action and reflection. Such a performance improvement process begins with data acquisition and the development of information that can be analyzed and results in actions that are incorporated into systems of practice. Performance improvement is a means of producing care that is more effective, efficient, and safe by minimizing unnecessary variation in care and preventing adverse effects. Performance improvement has been incorporated into health care systems and the delivery of care as a routine and ongoing process, assisting individual providers, groups, and institutions in advancing their care practices through the use of evidence-based analysis and intervention strategies (DHB, 2015). In a learning trauma care system, registries allow near-real-time analysis of patient data for such purposes.

Rapid-cycle performance improvement processes, although critical, do not eliminate the need for formal research investigations (e.g., trials, studies) whose primary aim is to answer questions or generate new knowledge. In medicine, doing no harm is a central tenet, and in some cases, well-designed trials will be needed to show that a change in trauma care practice does not in fact cause harm. Thus, a learning trauma care system requires a robust research enterprise for the generation of knowledge to guide decisions on trauma care delivery approaches, from both the system and individual patient perspectives. This research enterprise needs to be informed by an understanding of the value and limitations of different methodologies (discussed in more detail in Chapter 4) for answering different kinds of research questions so that trade-offs in agility and strength of evidence can be weighed and the appropriate methodology employed.

Finally, the ability to share information for purposes of knowledge generation and dissemination (discussed below) is paramount to the success of a learning trauma care system. In a learning trauma care system, such information sharing is supported by technological solutions, a culture of sharing, and a conducive regulatory environment.

Processes and Tools for Timely Dissemination of Trauma Knowledge

Although the continual pursuit of new knowledge through research and performance improvement is a critical aspect of a learning trauma care system, the generation of evidence on best care practices is not sufficient to drive improvements in patient outcomes. In such a learning system, the results of these efforts are disseminated and applied at the point of care.

In a learning trauma care system, knowledge is transmitted using a com-

bination of synchronous and asynchronous7 methodologies. To achieve improvements in trauma care, the system does not rely on individual providers to discover, assimilate, retain, and put into practice the ever-increasing supply of clinical evidence. Instead, trauma care providers have access to clinical practice guidelines and clinical decision support tools that capture, organize, and disseminate the best available information on trauma care practices to guide decision making at the point of care and reduce unwarranted variation in care and outcomes.

In the context of trauma, where rapid problem solving can make the difference between life and death, it is critical for providers to have just-in-time, synchronous access to experts in trauma care delivery—for example, through telemedicine—who can provide guidance to address questions and challenges at the point of care. The potential benefit of such synchronous access to expert knowledge is immediately improving patient outcomes.

Systems for Ensuring an Expert Trauma Care Workforce

At the heart of all health systems are the diverse teams of skilled professionals that make up the health care workforce. Achieving the vision laid out in the IOM’s (2001) Crossing the Quality Chasm report—health care that is safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable—requires a workforce that is “educated to deliver patient-centered care as members of an interdisciplinary team, emphasizing evidence-based practice, quality improvement approaches, and informatics” (IOM, 2003, p. 45). To this end, the IOM (2013) report Health Professions Education proposed core competencies that all clinicians should possess, regardless of their discipline, to meet the needs of the 21st-century health care system. These include the capability to

- provide patient-centered care—identify, respect, and care about patients’ differences, values, preferences, and expressed needs; relieve pain and suffering; coordinate continuous care; listen to, clearly inform, communicate with, and educate patients; share decision making and management; and continuously advocate disease prevention, wellness, and promotion of healthy lifestyles, including a focus on population health.

- work in interdisciplinary teams—cooperate, collaborate, communicate, and integrate care in teams to ensure that care is continuous and reliable.

__________________

7 Synchronous learning occurs in real time through mechanisms that give the teacher and the learner simultaneous access to one another (e.g., one-to-one coaching via phone, classroom teaching), whereas asynchronous learning allows learners to access information whenever they would like to do so, not requiring the presence of an instructor (e.g., websites, guidelines).

- employ evidence-based practice—integrate best research with clinical expertise and patient values for optimum care, and participate in learning and research activities to the extent feasible.

- apply quality improvement—identify errors and hazards in care; understand and implement basic safety design principles, such as standardization and simplification; continually understand and measure quality of care in terms of structure, process, and outcomes in relation to patient and community needs; design and test interventions to change processes and systems of care, with the objective of improving quality.

- utilize informatics—communicate, manage knowledge, mitigate error, and support decision making using information technology. (IOM, 2003, pp. 45-46)

A learning trauma care system supports all members of the trauma care team, including prehospital and hospital-based professionals, in achieving, sustaining, and demonstrating through credentialing discipline-specific expertise but also competencies surrounding continuous learning and improvement. Education, training, and skill sustainment programs evolve as new knowledge on best trauma care practices is generated. In addition, ensuring that trauma care providers have access to a sufficient volume of patient cases supports the development of tacit knowledge, a critical component of mastering any skill.

Patient-Centered Trauma Care

In a learning health system, the central focus is on those being served. A learning trauma care system ensures patient-centeredness by structuring trauma care around the patient experience and proactively engaging patients, families, and communities. The adoption of a patient-centered approach supports the following long-term outcomes:

- “survival is enhanced and morbidity is reduced;

- humanity and individual dignity are maintained and enhanced; and

- physical, functional, and psychological recovery and [quality of life] are maximized” (Richmond and Aitken, 2011, p. 2748).

Trauma Care Structured Around the Patient Experience

From the trauma patient’s perspective, an optimal care experience entails timely access to high-quality prehospital, definitive, and rehabilitative care, with seamless transitions between each of these settings to ensure that the patient’s physical and psychological health care needs are met. Breakdowns in or between any components of the system can negatively affect

a patient’s outcome, contributing to preventable morbidity and mortality. Seamless transitions across this continuum of care can be realized only in an environment of patient-centeredness.

Similarly, ongoing and effective communication is key to an effective patient-centered environment. Multiply injured trauma patients and their families often interact with multiple specialties, and it is imperative that a single individual be charged with ensuring that the needs of patients and families are met and that they are appropriately educated about the patient’s condition and treatment. The way in which news of a sudden traumatic injury or death is delivered can significantly impact how patients and family members cope with their lives moving forward. The 2nd Trauma Course was developed by the American Trauma Society to help trauma providers deliver such information in the most effective and supportive manner possible.8

Patient-centered trauma care focuses holistically on the needs of the individual patient, combining immediate treatment processes with attention to longer-term needs such as pain management and, importantly, emotional support (Bradford et al., 2011; Gajewski and Granville, 2006; Marks et al., 2005; Wegener et al., 2009; Williams et al., 2002). The ways in which individuals adapt psychologically to the aftermath of a significant injury vary and depend on several interrelated factors associated with personal and family resources, coping styles and self-efficacy, and resiliency, as well as barriers and facilitators in the social, economic, and physical environments. However, symptoms of depression, acute anxiety, and posttraumatic stress are common in trauma patients, and if not managed early in the recovery process, can lead to poor long-term outcomes (Hoge et al., 2004; Wegener et al., 2011; Wiseman et al., 2013; Zatzick et al., 2008). Patient-centered trauma care therefore addresses the holistic needs of patients and their families, beginning early in the acute care setting, and the trauma team plays an important role in screening for these conditions in the early post-acute phase of care and referring patients to appropriate services and programs (Coimbra, 2013).

A focus on patient needs also necessitates consideration of and adequate preparation for all the patient populations a trauma system might be expected to serve. Trauma disproportionately affects the young and is increasing in prevalence among the elderly (Rhee et al., 2014). Trauma systems and their personnel need to be sufficiently equipped, trained, and supported to provide optimal care for these patients. While the treatment of special populations is more common in the civilian sector, the military trauma system needs to be equally prepared given the frequency with which

__________________

8 See http://www.amtrauma.org/?page=2ndTrauma (accessed February 20, 2016).

military providers deliver care for host nationals, including children, in wartime (Borgman et al., 2012; Burnett et al., 2008).

Engagement of Patients, Families, and Communities

In a trauma care system that continuously learns and delivers improved outcomes, understanding of the priorities and unique perspectives of patients, families, and communities is reflected in the system’s functioning and design.

While the nature of traumatic injury often limits the extent to which patients can engage in their own care in the acute phase, opportunities for shared decision making exist in the primary care setting (e.g., prior to deployment) and in the hospital. To the degree possible, trauma patients need to be engaged in decisions about their care. To this end, they need to understand the full range of treatment options and the risks and benefits of each so that the decisions to which they contribute will accord with their values, preferences, and life circumstances. As trauma patients may be physically incapable of engaging in their own care, the greater involvement of families is a crucial component of patient-centered trauma care.

Patients, families, and other caregivers can offer a firsthand account of their experiences within a trauma care system, contributing to the identification of areas in need of improvement. A patient-centered approach ensures that this unique perspective is leveraged to further improve the functioning and design of the trauma care system. Patient and family participation in trauma research, for example, is an important feature of a learning trauma care system (Faden et al., 2013). Patients and families can help identify clinical research questions. Furthermore, this research needs to be reflective of these stakeholders’ priorities and concerns, particularly in those situations where decisions involve difficult trade-offs (e.g., high upfront risk but better potential long-term outcomes). Other opportunities to engage these stakeholders at the organization and system levels include

- the development of patient and family advisory councils,

- continuous measurement of patients’ outcomes and experiences, and

- patient involvement in improvement initiatives.

Leadership-Instilled Culture of Learning

Organizational culture has a significant influence on the performance of a learning system. Leadership has the unique ability to facilitate a culture of learning, to engage multiple and diverse stakeholders, and to remove barriers to improving care across an entire system, but most notably at the

point of care. Clear communication of leadership’s commitment to continuous improvement is critical in driving the many actors within a learning trauma care system to work collaboratively toward the common goal of improving patient outcomes. Effective leadership defines and prioritizes learning as a central mission of the trauma care system and sets quantifiable aims against which progress can continually be measured, thereby invoking a sense of urgency and motivating change in performance that might otherwise be slower to occur. Also critical is promoting a nonpunitive environment in which experimentation can be embraced in the absence of fear. To this end, it is important that leaders celebrate the generation of knowledge that emerges through small-scale testing of new concepts, innovations and ideas. In such environments, leadership expects and welcomes the questioning of standard processes, assumptions, and “business as usual” patterns of behavior. In addition, leadership will regularly study the progress of the system alongside actors in the system, creating a safe environment in which there is shared responsibility for underperformance (thus avoiding time wasted in assigning blame). Promoting a culture of teamwork, cooperation, and inclusiveness ensures that the contributions of all actors in the system are valued.

Transparency and Aligned Incentives for Quality Trauma Care

A learning trauma care system has leadership that is committed to transparency and aligns incentives to ensure that learning takes place and is sustainable, while at the same time minimizing waste and variability in practice that contribute to suboptimal outcomes. Transparency—“ensuring that complete, timely, and understandable information is available to support wise decisions”—empowers providers and organizations to improve their performance over time (IOM, 2013, p. 142). Transparency of cost and outcomes also allows patients and consumers to make informed decisions regarding their own care. There are four different, though related, forms of transparency:

- clinician-to-patient

- clinician-to-clinician

- organization-to-organization

- public (NPSF, 2015)

Clinician-to-patient transparency enhances communication, disclosure, and patient engagement in decision making. Transparency of performance between peers—both clinician-to-clinician and organization-to-organization—drives performance improvement. Drawing on data from trauma registries and other information systems, performance improvement programs in a

learning trauma care system make performance information available at the provider, team, center, and system levels. Such transparency assists individual providers in understanding and improving their personal performance, as well as their contribution to the overall trauma care system (DHB, 2015; IOM, 2007). Transparency at the organization level supports the evolution and improvement of the system through benchmarking against the performance of other similar organizations.

Broadly defined, benchmarking is the “systematic comparison of structure, process, or outcomes of similar organizations” (Camp, 1989; Nathens et al., 2012, p. 443). External benchmarking compares the performance of similar institutions, provides information on whether or to what extent an institution suffers from a performance issue, and suggests reasonable goals for performance improvement (Nathens et al., 2012). Information gleaned from external benchmarking can thus be highly motivating, particularly for those centers that may not even be aware that they are performing at a suboptimal level relative to their peer institutions. Benchmarking also identifies those who have achieved superior results, enabling the identification and adoption of best practices. This knowledge and awareness of a center’s performance relative to that of another center can serve as a strong incentive to improve care and outcomes in today’s competitive health care environment (Nathens et al., 2012).

While transparency is an important and powerful driver of change, a learning trauma care system employs a variety of levers to encourage and reward continuous improvement. These levers include financial incentives, personal recognition (e.g., promotion, rewards), regulatory requirements, tort, and competition.

Aligned Authority and Accountability for Trauma System Leadership

Strong, visible leadership is prerequisite to creating and sustaining a learning trauma care system that supports innovation and continuous improvements in care. The success of a learning trauma care system depends on the existence of defined leadership with comprehensive authority to maintain the system’s infrastructure, oversight, planning, and future development; create and enforce policy; and serve as a point of accountability. This leadership needs to be in a position to deliver the resources, support, and incentives needed to drive change and encourage continuous improvement throughout the system. Defined trauma system leadership also is necessary to ensure that the many actors and stakeholders involved in the system work together seamlessly to provide quality trauma care.

CONCLUSION

To operationalize the framework of a learning trauma care system outlined in this chapter and to assess how effectively current military and civilian systems foster learning and improvement, the committee developed the questionnaire in Box 3-4, drawing on the components described above. In the following chapters, the committee uses this assessment tool to identify ways in which the military and/or civilian systems are optimized for learning and align with the framework for a learning trauma care system described in this chapter. In the ensuing chapters, the committee also describes gaps in the military and civilian systems that hinder the delivery of optimal care to injured patients and serve as barriers to continuous learning and improvement and the translation of best practices and lessons learned within and across the military and civilian sectors. This analysis is also informed by a paper commissioned by the committee, an excerpt of which is included in Appendix D.

REFERENCES

100,000 Homes. 2014a. See the impact. http://100khomes.org/see-the-impact (accessed February 17, 2016).

100,000 Homes. 2014b. Track your progress. http://100khomes.org/read-the-manifesto/track-your-progress (accessed February 17, 2016).

ACS (American College of Surgeons). 2015. National Trauma Data Bank. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/trauma/ntdb (accessed February 3, 2016).

Arora, S., C. M. Geppert, S. Kalishman, D. Dion, F. Pullara, B. Bjeletich, G. Simpson, D. C. Alverson, L. B. Moore, D. Kuhl, and J. V. Scaletti. 2007. Academic health center management of chronic diseases through knowledge networks: Project ECHO. Academic Medicine 82(2):154-160.

Arora, S., S. Kalishman, K. Thornton, D. Dion, G. Murata, P. Deming, B. Parish, J. Brown, M. Komaromy, K. Colleran, A. Bankhurst, J. Katzman, M. Harkins, L. Curet, E. Cosgrove, and W. Pak. 2010. Expanding access to hepatitis C virus treatment—Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO) project: Disruptive innovation in specialty care. Hepatology 52(3):1124-1133.

Arora, S., K. Thornton, G. Murata, P. Deming, S. Kalishman, D. Dion, B. Parish, T. Burke, W. Pak, J. Dunkelberg, M. Kistin, J. Brown, S. Jenkusky, M. Komaromy, and C. Qualis. 2011. Outcomes of treatment for hepatitis C virus infection by primary care providers. New England Journal of Medicine 364(23):2199-2207.

Arora, S., K. Thornton, M. Komaromy, S. Kalishman, J. Katzman, and D. Duhigg. 2014. Demonopolizing medical knowledge. Academic Medicine 89(1):30-32.

Becerra-Fernandez, I., and R. Sabherwal. 2001. Organizational knowledge management: A contingency perspective. Journal of Management Information Systems 18(1):23-55.

Berwick, D. M., B. James, and M. J. Coye. 2003. Connections between quality measurement and improvement. Medical Care 41(1):I30-I38.

Borgman, M. A., R. I. Matos, L. Blackbourne, and P. C. Spinella. 2012. Ten years of military pediatric care in Afghanistan and Iraq. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 73(6 Suppl. 5):S509-S513.

Bradford, A. N., R. C. Castillo, A. R. Carlini, S. T. Wegener, H. Teter, Jr., and E. J. MacKenzie. 2011. The trauma survivors network: Survive. Connect. Rebuild. Journal of Trauma 70(6):1557-1560.

Burnett, M. W., P. C. Spinella, K. S. Azarow, and C. W. Callahan. 2008. Pediatric care as part of the US Army medical mission in the global war on terrorism in Afghanistan and Iraq, December 2001 to December 2004. Pediatrics 121(2):261-265.

Camp, R. C. 1989. Benchmarking: The search for industry best practices that lead to superior performance. Milwaukee, WI: ASQC Quality Press.

Coimbra, R. 2013. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) screening and early intervention after physical injury: Are we there yet? Annals of Surgery 257(3):400-402.

Dawson, D. E. 2006. National Emergency Medical Services Information System (NEMSIS). Prehospital Emergency Care 10(3):314-316.

DHB (Defense Health Board). 2015. Combat trauma lessons learned from military operations of 2001-2013. Falls Church, VA: DHB.

Faden, R. R., N. E. Kass, S. N. Goodman, P. Pronovost, S. Tunis, and T. L. Beauchamp. 2013. An ethics framework for a learning health care system: A departure from traditional research ethics and clinical ethics. Hastings Center Report 43(1):S16-S27.

Gajewski, D., and R. Granville. 2006. The United States Armed Forces Amputee Patient Care Program. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 14(Spec. No. 10):S183-S187.

Greene, S. M., R. J. Reid, and E. B. Larson. 2012. Implementing the learning health system: From concept to action. Annals of Internal Medicine 157(3):207-210.

Hoge, C. W., C. A. Castro, S. C. Messer, D. McGurk, D. I. Cotting, and R. L. Koffman. 2004. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. New England Journal of Medicine 351(1):13-22.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2001. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2003. Health professions education: A bridge to quality. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2007. Hospital-based emergency care: At the breaking point. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2011. Engineering a learning healthcare system: A look at the future: Workshop summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2013. Best care at lower cost: The path to continuously learning health care in America. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

James, B. 2003. Information system concepts for quality measurement. Medical Care 41(1):I71-I79.

James, B. C., and L. A. Savitz. 2011. How Intermountain trimmed health care costs through robust quality improvement efforts. Health Affairs (Millwood) 30(6):1185-1191.

Mann, N. C., L. Kane, M. Dai, and K. Jacobson. 2015. Description of the 2012 NEMSIS public-release research dataset. Prehospital Emergency Care 19(2):232-240.

Marks, R., J. P. Allegrante, and K. Lorig. 2005. A review and synthesis of research evidence for self-efficacy-enhancing interventions for reducing chronic disability: Implications for health education practice (Part I). Health Promotion Practice 6(1):37-43.

McCannon, C. J., and R. J. Perla. 2009. Learning networks for sustainable, large-scale improvement. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety 35(5):286-291.

Morris, A. H., C. J. Wallace, R. L. Menlove, T. P. Clemmer, J. F. Orme, Jr., L. K. Weaver, N. C. Dean, F. Thomas, T. D. East, N. L. Pace, M. R. Suchyta, E. Beck, M. Bombino, D. F. Sittig, S. Bohm, B. Hoffmann, H. Becks, S. Butler, J. Pearl, and B. Rasmusson. 1994. Randomized clinical trial of pressure-controlled inverse ratio ventilation and extracorporeal CO2 removal for adult respiratory distress syndrome. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 149(2 Pt. 1):295-305.

Nathens, A. B., H. G. Cryer, and J. Fildes. 2012. The American College of Surgeons Trauma Quality Improvement Program. Surgical Clinics of North America 92(2):441-454.

Nelson, E. C., J. J. Mohr, P. B. Batalden, and S. K. Plume. 1996. Improving health care, Part 1: The clinical value compass. Joint Commission Journal on Quality Improvement 22(4):243-258.

Nonaka, I. 1994. A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organization Science 5(1):14-37.

NPSF (National Patient Safety Foundation). 2015. Shining a light: Safer health care through transparency. Boston, MA: NPSF.

Pocock, S. J. 1983. Clinical trials: A practical approach. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Polanyi, M. 1966. The logic of tacit inference. Philosophy 41(155):1-18.

Project ECHO. 2016. Our story. http://echo.unm.edu/about-echo/our-story (accessed April 22, 2016).

Rhee, P., B. Joseph, V. Pandit, H. Aziz, G. Vercruysse, N. Kulvatunyou, and R. S. Friese. 2014. Increasing trauma deaths in the United States. Annals of Surgery 260(1):13-21.

Richmond, T. S., and L. M. Aitken. 2011. A model to advance nursing science in trauma practice and injury outcomes research. Journal of Advanced Nursing 67(12):2741-2753.

Rogers, E. M. 2010. Diffusion of innovations. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Wegener, S. T., E. J. MacKenzie, P. Ephraim, D. Ehde, and R. Williams. 2009. Self-management improves outcomes in persons with limb loss. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 90(3):373-380.

Wegener, S. T., R. C. Castillo, J. Haythornthwaite, E. J. MacKenzie, and M. J. Bosse. 2011. Psychological distress mediates the effect of pain on function. Pain 152(6):1349-1357.

Williams, R. M., D. R. Patterson, C. Schwenn, J. Day, M. Bartman, and L. H. Engrav. 2002. Evaluation of a peer consultation program for burn inpatients. 2000 ABA paper. Journal of Burn Care & Research 23(6):449-453.

Wiseman, T., K. Foster, and K. Curtis. 2013. Mental health following traumatic physical injury: An integrative literature review. Injury 44(11):1383-1390.

Zatzick, D., G. J. Jurkovich, F. P. Rivara, J. Wang, M. Y. Fan, J. Joesch, and E. MacKenzie. 2008. A national US study of posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and work and functional outcomes after hospitalization for traumatic injury. Annals of Surgery 248(3):429-437.