5 Creating and Sustaining an Expert Trauma Care Workforce

“He who wishes to be a surgeon, must first go to war.”

—Hippocrates

Trauma is complex. It can result in life- and limb-threatening injury, multiorgan failure, massive tissue damage, and physiologic dysfunction. To save lives and minimize disability in the face of such destruction requires a system of care with a diverse network of professionals capable of rapidly responding and delivering lifesaving interventions. In the military, the survival and well-being of service members depends on the creation and sustainment of a coalition of medical providers and allied health professionals1 with expertise in trauma care. This chapter presents the committee’s assessment of the extent to which the current education, training, and career development approach of the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) is sufficient to ensure a ready military trauma care workforce2 and how that system facilitates knowledge sharing between the military and civilian sectors.

THE MILITARY HEALTH SYSTEM READINESS MISSION

The principle mission of the Military Health System is readiness (MHS, 2014). Increased readiness is one of four goals captured in the Military

__________________

1 Allied health professionals are the “segment of the workforce that delivers services involving the identification, evaluation and prevention of diseases and disorders; dietary and nutrition services; and rehabilitation and health systems management” (ASAHP, 2014).

2 A full analysis of systems for ensuring the competency of the civilian trauma care workforce is beyond the scope of this report.

Health System Quadruple Aim,3 which also includes better health, better care, and lower cost (DoD, 2014). Readiness is multifaceted; in the medical context, however, it means that the total military workforce is medically ready to deploy and, most relevant to the work of this committee, that the military medical force is ready to deliver expert health care (including combat casualty care) in support of the full range of military operations, domestically and abroad (DoD, 2014; Maldon et al., 2015). To sustain a medically ready force, the Military Health System delivers comprehensive health care to DoD service members, but health care services are also made available to other eligible beneficiaries. In fact, DoD provides health care to 9.6 million people worldwide, including active duty service members, dependents, retired service members, employees, and others. Currently, beneficiary care consumes approximately 10 percent of the annual DoD budget, approaching $50 billion (DoD, 2014). Because of its size, scope, expense, and everyday presence, beneficiary care drives the Military Health System, dwarfing its mission of providing a trained and ready medical force. Some exceptions exist, but in general, the Military Health System functions like a large health maintenance organization until wartime, when the need to care for those in harm’s way generates an urgency to save lives (Mabry, 2015). It should be emphasized that although beneficiary care can be and, in some cases, has been contracted to civilian-sector health systems, the readiness mission can be carried out only by the DoD.

Readiness to deliver medical care in support of the combat mission necessitates both a sufficient number of providers to meet battlefield needs and that those providers have expertise in combat casualty care. Notably, however, there is no common definition among the services for readiness of the medical force,4 nor is there a core set of standards for the acquisition and maintenance of trauma care skills (Maldon et al., 2015).

Provision of the highest-quality trauma care for the wounded is an expectation of the nation’s service members and the American public. As stated by General Peter Chiarelli (2015), the U.S. Army’s former vice chief of staff, “I know if I am providing [servicemen and -women] the kind of combat casualty care that they expect on a battlefield, every single one of them is going to be so much more a solider that is able to accomplish their mission than they would be if I did not.” Failure to sustain the readiness of the medical force threatens the total deployed force and national security (Maldon et al., 2015). When the next military conflict inevitably transpires,

__________________

3 The quadruple aim represents an adaption of the Triple Aim of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI, 2016).

4 A common definition and reporting metrics exist for individual medical readiness (i.e., the workforce is medically ready to deploy). This is distinct from a common definition for readiness of the medical force, which does not exist.

there will be little time to reconstruct and ensure an optimal combat casualty care capability from a diminished state of readiness. DoD cannot wait until the next war to begin the process of generating a ready medical force to meets its wartime needs. If the lessons learned over the past 15 years are not sustained and history repeats itself, the next war will see the loss of lives and limbs that should have been saved.

THE TRAUMA CARE WORKFORCE

Optimal trauma care and patient outcomes require careful coordination of prehospital and hospital-based services. Thus while the term “trauma team” is often used to describe the in-hospital group of medical professionals responsible for the initial assessment, resuscitation, and surgical management of critically injured patients, the complete team of professionals responsible for trauma care spans both the prehospital and hospital environments. In the military and civilian sectors, the clinical trauma care workforce includes surgeons, emergency physicians, nurses, prehospital providers, technicians, anesthesiologists, intensivists, radiologists, and rehabilitation specialists, among others. Equally critical, however, is the wide range of professionals who directly support the clinical mission (supply, operations, information technology, management, administration), and those who collect and analyze data for performance improvement and research purposes (see Figure 5-1). This multidisciplinary approach to trauma care ensures the successful integration of knowledge and resources across the continuum of care and among different specialties and has been shown to improve outcomes (MacKenzie et al., 2006).

The Civilian Trauma Care Workforce

Initial trauma care in the prehospital setting is delivered by emergency medical technicians and paramedics. Although emergency physicians, advanced practice providers, and other specialists may handle many injuries in the hospital setting, most severe trauma cases that arrive at U.S. civilian trauma centers are ultimately cared for by trauma surgeons. Trauma surgeons possess not only general surgery training but also additional fellowship training in surgical critical care, and have demonstrated broader interest in trauma research and trauma systems. While the trauma specialty is relatively new, the development of such expertise has improved outcomes for critically injured patients in the civilian sector (Knudson, 2010). Patients sustaining serious trauma require a larger group of specialists than is required to treat less severe cases, including orthopedic surgery, anesthesiology, surgical critical care, radiology, blood banking/coagulation, infectious disease, and neurological surgery, among others. In addition, the expertise

of nursing and allied health professionals in resuscitation, operating room procedures, and critical care is essential for optimizing the care of the most critically injured. Accordingly, civilian Level I trauma centers are designed, resourced, and prepared to deliver immediate lifesaving surgical procedures across a wide range of specialties; for example, they are required to have a trauma surgeon, surgical specialists, and all other medical specialists and providers available at all times (ACS, 2014).

The Military Trauma Care Workforce

The military trauma care workforce is far more complex in structure than its civilian counterpart. Although the interdisciplinary nature of the trauma care workforce is common to both sectors, added complexity arises from the multiservice nature of the military’s medical force and the augmentation of active duty personnel with reservists and members of the National Guard (Cannon, 2016).

The military also deploys providers with a diverse array of medical backgrounds, specialties, and experience (Gawande, 2004). The vast majority of these providers, whose daily practice typically consists of delivering beneficiary care at military treatment facilities (MTFs), rarely encounter

trauma and thus lack the necessary expertise to deliver trauma care on the battlefield (see Table 5-1 for an overview of the variable levels of clinical competence). In this respect they differ from their civilian counterparts: the trauma care workforce in the civilian sector includes a set of core professionals whose primary focus is the daily delivery of trauma care (e.g., emergency physicians, trauma surgeons, trauma nurses, EMS providers). It is important to acknowledge the psychological effects of assigning physicians, nurses, technicians, and medics with non-trauma-related specialties to combat care. Many will likely witness and feel professionally responsible for the deaths of young soldiers and civilians under their care, and as a result are likely to suffer increased psychological stress, emotional trauma, and professional burnout (Lang et al., 2010; Lester et al., 2015).

While the management of civilian trauma patients is similar in some respects to the management of battlefield trauma, the evaluation, resuscitation, and treatment of wounded combatants present a unique challenge

TABLE 5-1 Five Levels of Clinical Competence

| Skill Level | Description | Trauma-Related Example |

|---|---|---|

| Novice | The novice has no experience in the environment in which he or she are expected to perform. | Administrator or technician who has never worked in a trauma center. |

| Advanced beginner | The advanced beginner demonstrates marginally acceptable performance and has enough experience to note recurrent meaningful situational components. | Medic that has had didactic trauma training but no clinical trauma experience. |

| Competent | Competence is achieved when one begins to see one’s actions in terms of long-range goals or plans. This individual demonstrates efficiency, coordination, and confidence in his/her actions. | Board-eligible/certified physician, but has only rotated as a resident at a trauma center. |

| Proficient | The proficient individual perceives situations holistically and possesses the experience to understand what to expect in a given situation. | Board-eligible/certified physician or new nurse, starting their career at a high-volume and best-quality Level I trauma center. |

| Expert | The expert has an intuitive and deep understanding of the total situation and is able to deliver complex medical care under highly stressful circumstances. | Trauma nurse coordinator or fellowship trained trauma surgeon with years of experience at a high-volume and best-quality Level I trauma center. |

SOURCES: Adapted from Benner, 1982; Dreyfus, 1981; Dreyfus and Dreyfus, 1980.

when military teams are deployed to theater. In the civilian sector, medical care is provided along specialty lines that have emerged based on disease type, organ dysfunction, or procedural expertise. In a 2008 survey of civilian trauma centers, only 18 percent of Level I centers indicated that their trauma surgeons could perform “a full complement of vascular, thoracic, and abdominal procedures” (Cothren et al., 2008, p. 955). In contrast to cases seen in civilian trauma centers, battlefield injury patterns—including a higher concentration of massive body destruction and exsanguination—require a broad set of surgical skills and competencies that can be applied in difficult environments and conditions (Mabry et al., 2000). As noted by Schwab (2015), however, there is no defined skill set required to deploy and serve as a combat surgeon. Throughout the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, general surgeons who have been deployed have had backgrounds in a variety of specialty domains within the classification of general surgery, including pediatric, thoracic, and vascular surgery (Sorbero et al., 2013). This challenge is not limited to surgeons. It is not unusual to have members of the trauma team inexperienced and uncomfortable in trauma care deployed to the battlefield without an assessment of their competence to care for severely injured casualties. The Air Force has made the greatest strides in addressing this issue through the creation of a series of readiness skills verification checklists, which provide guidance on the clinical competencies different providers (e.g., nurses) need to have and what care they may be expected to provide upon deployment (Bridges, 2016).

Additionally, the military’s surgical workforce is notably young, with a mean age of 36 at the time of first deployment (Schwab, 2015). In a survey of 137 military surgeons across all three services, 65 percent had been deployed for the first time without completing a fellowship (Tyler et al., 2012). This represents another notable difference from the civilian sector, where senior-level trauma and surgical critical care experts (almost all of whom are fellowship trained) provide leadership and oversight at Level I and II trauma centers.

Within the trauma care workforce, nurses are crucial members of multidisciplinary clinical teams and often assume responsibility for managing patient flow between phases of care (Richmond, 2016), thus faciitating a patient-centered approach to trauma care (discussed in more detail in Chapter 6). Nurses also serve as trauma nurse coordinators (TNCs) in Role 3 (e.g., combat support hospitals), Role 4 (e.g., Landstuhl Regional Medical Center), and Role 5 (continental United States) MTFs5 and as Air Force flight nurses within the aeromedical evacuation system (Fecura et al., 2008). In the deployed setting, TNCs manage the Joint Trauma System’s

__________________

5 In military Role 4 and Role 5 facilities, trauma nurse coordinators are civilian trauma nurses.

(JTS's) performance improvement program and the DoD Trauma Registry (DoDTR). In preparation for this role, nurses from all the services may take the Trauma Outcomes and Performance Improvement Course-Military (discussed in more detail below) (Fecura et al., 2008).

Medical personnel in the enlisted corps can serve as medics (Army), medical technicians (Air Force), hospital corpsmen (Navy), independent duty medical technicians (Air Force), or licensed practical nurses (Army). These individuals are high school graduates (or possess the equivalent of a high school diploma) and have completed basic military training (Cannon, 2016). Many of these prehospital providers that deploy to an active combat zone have provided little to no care to trauma patients. The first trauma patient a military medic cares for may be on the battlefield (Bier et al., 2012; Cannon, 2016).

As of 2012, approximately 280 providers (Air Force, 78; Army, 100; Navy, 100) were able to deploy as fully trained, active duty general surgeons to combat or other operational zones. This group includes 30 to 35 surgeons fellowship trained in trauma and surgical critical care or burn care (DuBose et al., 2012). The military trauma care workforce further consists of nearly 4,000 members of the Nurse Corps and 36,000 members of the Enlisted Corps (Sorbero et al., 2013). The active duty trauma workforce is supplemented by National Guard members and reservists. The National Guard and reserve units deploy physicians, nurses, and medics; some of them bring a high level of quality and significant expertise (Cannon, 2016), while others do not regularly provide trauma care or perform general surgery in their daily practice (DuBose et al., 2012).

The composition of military clinical teams in the deployed setting varies across the echelons of care (see Box 5-1). The optimal composition of the medical team in Role 1 (e.g., battalion aid stations), Role 2 (e.g., forward surgical teams), and Role 3 (e.g., combat support hospitals) facilities has been debated (Schoenfeld, 2012). What is clear is that a large proportion of preventable trauma deaths are associated with hemorrhage and exsanguination—often from junctional and torso wounds—necessitating prehospital providers and forward surgical teams armed with trauma care expertise.

The importance of having trained providers with experience and expertise relevant to their assigned roles is highlighted in multiple studies. In an observational analysis by Gerhardt and colleagues (2009), a battalion aid station augmented with providers with emergency medicine expertise experienced a lower case fatality rate compared to the aggregate theater-wide case fatality rate (7.14 percent versus 10.45 percent). At this battalion aid station, a board-certified emergency physician and emergency medicine physician assistant delivered care, provided medical direction to medics, and mentored other providers (Gerhardt et al., 2009). A separate study

identified a disparity in outcomes based on the level of expertise available on helicopter transports. Standard Army MEDEVAC transport helicopters were staffed by a single medic trained as an emergency medical technician (EMT)-basic. In contrast, some deploying medics from the National Guard were certified as critical care flight paramedics (CCFPs)—the standard required to transport patients on civilian helicopters. Comparing outcomes in patients transported by standard Army MEDEVAC units and CCFP-staffed units, 48-hour mortality was 15 percent versus 8 percent, respectively, and transport by a CCFP was independently associated with a 66 percent estimated lower risk of mortality relative to the standard MEDEVAC system (Mabry et al., 2012). These results spurred efforts to implement higher training requirements for prehospital military medics, alternative staffing models, and expert medical direction for MEDEVAC transports going forward (Ficke et al., 2012).

CHALLENGES TO ENSURING AN EXPERT MILITARY TRAUMA CARE WORKFORCE

In an expert military trauma care workforce, as envisioned by the committee, every military provider is not expected to be an expert (as defined in Table 5-1) in trauma. An expert workforce will include providers with variable levels of expertise, as is the case in the civilian sector. However, to eliminate preventable deaths after injury and ensure the provision of the highest-quality trauma care, each interdisciplinary trauma team at all roles of care needs to include an expert for every discipline represented. These expert-level providers will oversee the care provided by their team members, all of whom must be minimally proficient in trauma care (i.e., appropriately credentialed with current experience caring for trauma patients).

At this time, a number of policy and operational barriers impede the military’s ability to ensure such an expert trauma care workforce, including an oscillating trauma workload, a challenging work environment in theater, providers’ beneficiary care responsibilities, and challenges with recruitment and retention in the absence of career paths for trauma providers.

Trauma Workload and Environment

Notable differences characterize the delivery of trauma care in the military and civilian sectors. The work environment in theater is very different from that experienced by civilian surgeons: the workload is higher, the traumas are more severe, and surgeons must deal with limited resources in an environment that is sometimes hostile. The nature of the traumas frequently encountered in theater—“multiply injured patients with high-energy transfer fragment, projectile, and blast wounds”—demands a

unique level of skill and damage control (Ramasamy et al., 2010, p. 455; Rosenfeld, 2010).

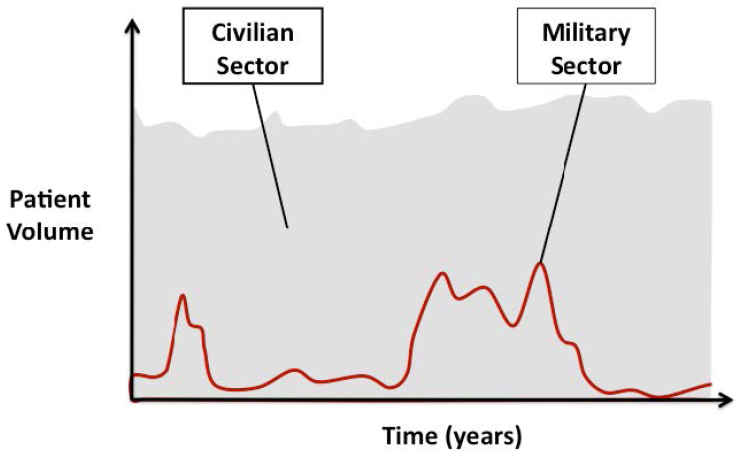

In addition to dealing with high-acuity, polytrauma cases and multiple-casualty events,6 the military faces challenges not seen in civilian settings as a result of the episodic nature of wartime trauma care requirements (see Figure 5-2). The volume of trauma patients seen by military providers varies dramatically depending on whether the United States is actively engaged in combat operations. In contrast, the civilian sector sees a more sustained volume of trauma cases over time, particularly in Level I and II trauma centers. Deployed military medical providers can face a sustained high trauma workload not commonly experienced by their civilian counterparts, depending on operational tempo. Ramasamy and colleagues (2010) found that a 6-week deployment to Afghanistan provided exposure to penetrating trauma equivalent to 3 years of working in a United Kingdom hospital. Those kinds of trauma patients are rarely seen in stateside MTFs. However, with the exception of regular exposure to the severe soft tissue injuries and amputation seen from combat, the case mix in civilian Level I and II centers more closely resembles that seen on the battlefield (Schreiber et al., 2008).

Competing Roles for Military Medical Providers

The military medical workforce is not large enough to simultaneously meet staffing requirements for both beneficiary care and the readiness mission of the Military Health System. Instead, most active duty medical personnel, including general surgeons, are permanently assigned to MTFs, including community hospitals and clinics, where they are responsible for beneficiary care. When the military is engaged in combat operations, medical personnel from MTFs can be temporarily reassigned to fill slots in deploying combat units. The Professional Filler System (PROFIS), for example, is used by the Army Medical Department to manage the reassignment process (DoD, 2015b; Sorbero et al., 2013).

The Military Health System is unique within the military with regard to its approach to readiness. Line units train constantly for their wartime missions (e.g., working on marksmanship or maneuvers), using repetition to develop and sustain skills so that when they must engage in combat, they can respond with world class precision and can adapt and overcome obstacles (Beekley, 2015). In the educational vernacular, they are expert, not just familiar. Repetition is equally critical to ensuring the competency

__________________

6 Although high-acuity, polytrauma cases and multiple-casualty events may be seen in certain civilian settings (e.g., Level I trauma centers within major urban areas), such cases occur with more frequency on the battlefield (McCunn et al., 2011).

SOURCE: Cannon, 2016.

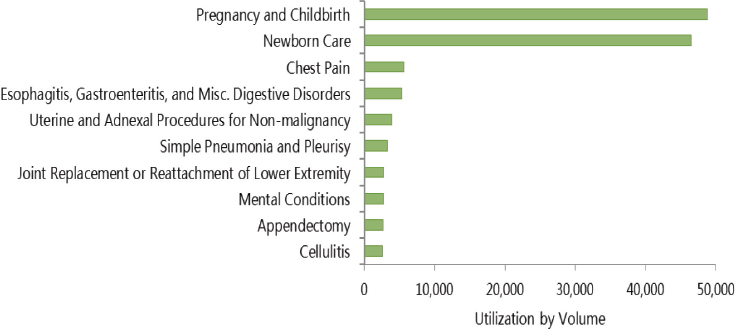

of medical providers; patient volume has been identified as a key factor associated with patient outcomes in both military and civilian trauma care settings (Nathens and Maier, 2001; Schreiber et al., 2002). However, military medical providers maintain their clinical skills through in-garrison care, which is largely devoid of trauma patients. Although this dual role of medical providers helps the Military Health System achieve cost efficiencies, it exacts a toll on the combat casualty care readiness mission. The common types of beneficiary surgical care provided at MTFs—obstetric, general, and elective—are rarely applicable to combat care (Eibner, 2008; Maldon et al., 2015) (see Figure 5-3). The military has only a handful of trauma centers in which medical personnel see sufficient volumes of trauma patients to maintain combat-relevant skill sets. Only one, San Antonio Military Medical Center, is currently verified as a Level I trauma center. As a result, the average infantry soldier is much better prepared for a combat mission than the average military general surgeon (Beekley, 2015). For prehospital providers, sustainment of skills is similarly challenging, as medics may be assigned to nonmedical duties (e.g., detailed to the motor pool) when they are not deployed. These front-line medical personnel have potentially the most significant mismatch between their daily (nondeployed) experience and the job expected of them on the battlefield. It is not unusual for these young medics to not be allowed to perform their medical tasks, even within

SOURCE: Data from DoD, 2015a.

military hospitals, yet are expected to function effectively under the most extreme circumstances on a hostile battlefield.

The misalignment of skill sets needed for beneficiary care and combat casualty care and the impact of the current system on medical readiness have been the subject of a number of investigations and reports. In 1992 and 1993, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) (at the time called the U.S. General Accounting Office) issued reports on deficiencies in medical readiness identified during the Gulf War in each of the services and resultant examples of substandard care (GAO, 1992, 1993a,b). The reports cited cases of deployed nurses and physicians who had never treated trauma patients, many of whom had not even received training in combat casualty care (GAO, 1998). Also highlighted were inappropriate staffing selections, such as the assignment of a gynecologist to fill a thoracic surgeon slot. These deficiencies were due in part to the depletion of combat-relevant specialties in the medical ranks in the years leading up to the Gulf War. In 2008, a RAND report similarly identified a significant gap between the skills needed to meet beneficiary needs at MTFs and the skills needed for deployment to a combat zone (Eibner, 2008). Many of these same issues still exist today.

Recruitment and Retention in the Absence of Career Paths for Trauma Providers

Since the transition to an all-volunteer military medical force, recruitment and retention of physicians, nurses, medics, and other allied health professionals has been challenging, particularly in times of war, when

the likelihood of deployment can serve as a deterrent. Competition with the lucrative private sector7 poses a considerable impediment to meeting military medical staffing needs, despite recruitment strategies such as signing bonuses and medical education scholarships (Holmes et al., 2009; Mundell, 2010).

Beyond these general challenges, the recruitment and retention of trauma and critical care specialists are impeded by additional hurdles that have received inadequate attention—a surprising observation given the core readiness mission of the Military Health System. The trauma and critical care specialties are relatively new (early 1990s) and despite being associated with improved outcomes for seriously injured individuals in the civilian sector, have not been embraced by the military services as a specific career path. For example, across the services, there is no skill identifier for nurses with specific trauma expertise, including trauma nurse coordinators, who serve a critical role in civilian trauma centers (Bridges, 2016). At only one DoD Level I trauma center can a senior military physician serve as the trauma medical director. As a result of the absence of defined trauma career pathways, a notable difference between the military and civilian sectors is the routine delivery of trauma and critical care by nonspecialists in the deployed setting. This lack of specialty expertise is not limited to the surgical teams but is a broader problem for combat casualty care, much of which is delivered after patients leave the operating room (e.g., within the intensive care unit) (Cap, 2015).

Relatedly, promotion requirements can impede the professional development of senior-level military clinicians. For example, the committee heard that nurses wishing to be promoted beyond the O4 level8 may have to leave clinical practice (Wilmoth, 2016), resulting in a dearth of senior-level individuals able to serve as trauma nurse coordinators.

The paucity of opportunities to sustain trauma and critical care skills during assignment to stateside MTFs poses additional challenges to retention of clinicians with these skills (Cannon, 2016). Members of the military (medics, technicians, nurses, and physicians) who desire a career in the trauma field have limited opportunities within the Military Health System to practice their chosen specialty or to advance to leadership positions. By contrast, the civilian sector has abundant professional career opportunities for medical, nursing, and EMS professionals who wish to spend their careers caring for trauma patients and leading the development of trauma systems. With the end of the wars and the return to a focus on beneficiary

__________________

7 Physician wages in the civilian sector, for example, may be as much as three times those of equivalent military physicians (Mundell, 2010).

8 O4 represents field grade officers at the rank of major (Air Force, Army, Marines) or lieutenant commander (Navy).

care, the loss of opportunities to exercise trauma care skills has already spurred many of these military experts to transition to the civilian sector (Mullen, 2015). Financial incentives and opportunities to train or practice (full- or part-time) at civilian trauma centers (discussed below) have the potential to positively influence these clinicians to remain in the military (Eibner, 2008; Schwab, 2015).

The development of an expert trauma workforce requires a significant investment of both time and resources, necessitating in some cases more than a decade of education and specialty medical training. The committee recognizes that the entire military medical system need not be combat care oriented; however, given that combat care can be delivered only by the Military Health System, that system needs to allocate the necessary resources to maintain a well-trained and adequately staffed workforce.

CURRENT MILITARY APPROACHES TO ACHIEVING A READY MEDICAL FORCE

To address deficiencies in combat casualty care capabilities noted during the Gulf War, a number of changes were instituted to improve the readiness of the medical force. An evaluation of the military’s current approach to readiness and a description of opportunities for exchange of trauma care knowledge with the civilian sector are presented in the sections below.

The Medical Education and Training Pipeline

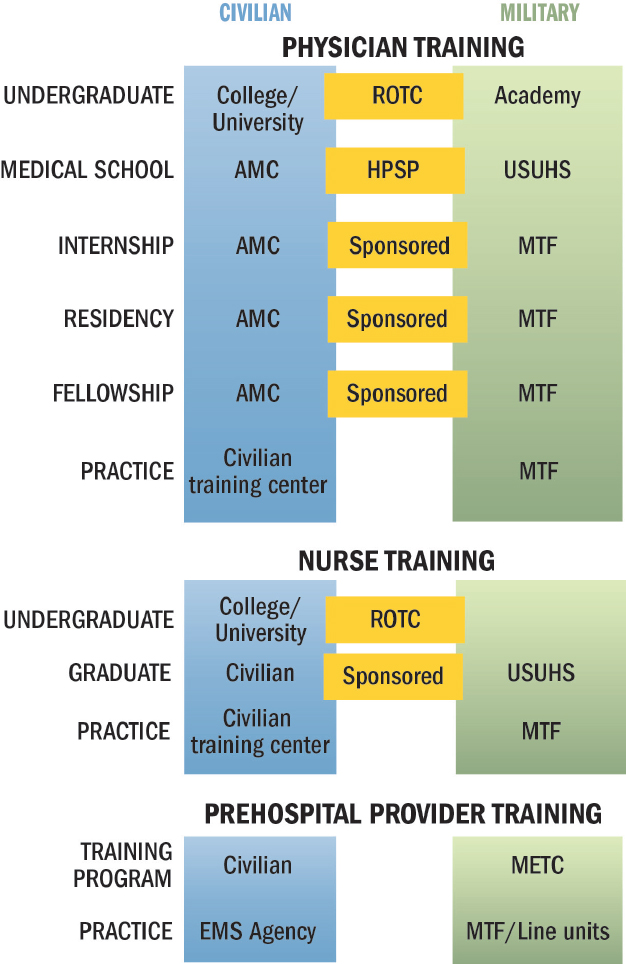

Trauma care providers undergo their education and training through a number of possible combinations of military and civilian experiences. This training pipeline provides some opportunity for cross-sector pollination (see Figure 5-4). However, one’s course along this pipeline will determine the degree of one’s exposure to military concepts and the extent of one’s interface with civilian counterparts.

Physician and Nursing Education and Training

Like the civilian trauma care workforce, the vast majority of military physicians and nurses receive initial medical education in civilian academic programs, although the military offers graduate-level medical, dental, and nursing education through the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USUHS). Military physicians who receive their medical education at civilian academic medical centers often (though not always) do so under the Armed Forces Health Professionals Scholarship Program (HPSP). This program pays tuition, fees, and a stipend for students attending accredited health professional programs; after graduation, students are obligated to

NOTES: Training provided in the civilian sector is shown in blue, while that conducted in the military sector is shown in green. Training conducted in the civilian sector with a military obligation (e.g., HPSP) or sponsorship is shown in orange. Transition between military and civilian training pathways can occur at any number of points along the pipeline, not just through those mechanisms labeled in orange. For example, civilians finishing medical school can volunteer for military service without HPSP.

AMC = academic medical center; EMS = emergency medical services; HPSP = Health Professionals Scholarship Program; METC = Medical Education & Training Campus; MTF = military treatment facility; ROTC = Reserve Officer Training Corps; USUHS = Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences.

SOURCE: Adapted from Cannon, 2016.

enter active duty unless it is deferred for the purposes of further medical training. During their civilian medical education, HPSP students have no organized military medicine curriculum (including military medical history and combat casualty care) and have limited exposure to military physicians (Cannon, 2016). Similarly, an undergraduate nursing degree can be pursued under a Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) scholarship, but beyond fundamental military training required of all ROTC candidates, such nurses receive little to no exposure to military nursing mentors during that time period.

Civilian academic medical centers also host military physicians for residency and fellowship training, although residency and fellowships are more commonly completed at MTFs, depending on the service requirements and the specialty. However, there is only one military trauma and surgical critical care fellowship (at San Antonio Military Medical Center), so all other training in these specialties is provided in civilian academic medical centers. Even those physicians selected for military residency may complete their trauma requirements (1- to 2-month rotations) at a civilian trauma center. The military has unquestionably benefited from trauma surgeons trained in the civilian sector—such individuals were key in applying the principles of systems-based approaches to trauma care to the creation of an in-theater trauma system. As with graduate medical education, however, exposure to combat casualty care-relevant experiences (e.g., through contact with experienced military trauma faculty) is limited for residents and fellows trained at civilian academic medical centers. According to Cannon (2016), in a paper commissioned for this study, “In the absence of any military-specific training or educational requirements, even those who are on a pathway for deployment soon after graduation are not afforded relevant military educational opportunities in the current military medical training pipeline.”

The best possible combat training experience comes from deployment, but there currently is no mechanism for deployment of residents or fellows in military training programs. This contrasts with the British model, in which surgical residents are routinely sent into combat zones to gain combat casualty care experience (Ramasamy et al., 2010), although such deployments might significantly extend the training timeline.

USUHS is a federal health science university with graduate programs in medicine, nursing, and dentistry. It educates a comparatively small number of military medical physicians and nurses each year: there have been about 7,200 total graduates since its establishment in 1972. Frequent deployments and a long service commitment may make USUHS less appealing to some medical applicants (Holmes et al., 2009). However, USUHS graduates tend to stay in military service longer than other service members (perhaps related to their obligations) and often rise to leadership roles (Rice, 2015). USUHS feeds military physicians into all three services, providing opportu-

nities to cross-pollinate innovations and best practices among the services. The training it offers is unique in several ways. Students are active duty military during their studies and are exposed early on to military-relevant topics. They also participate in field training exercises to prepare for the field environment in which they will be practicing. USUHS makes extensive use of its Simulation Center, which allows students to gain hands-on clinical experience in a safe environment.

Education and Training of Military Medics

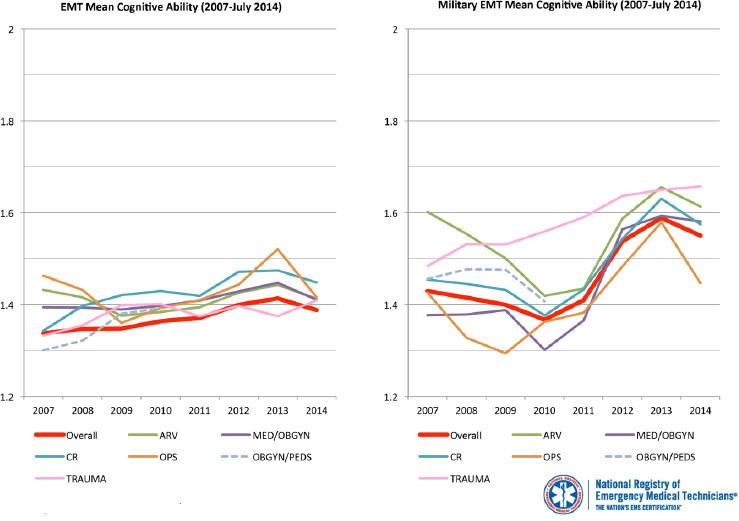

Basic medic training is completed over 14 to 20 weeks (depending on the service) at the Medical Education & Training Campus, and most medics must subsequently maintain national registry certification (METC, 2016; Sohn et al., 2007). Looking at performance over time on a national certification exam, one sees that military medics outpace their civilian counterparts (see Figure 5-5). However, with the notable exception of Special Forces medics, whose training lasts 1 year and who sustain their skills

NOTE = ARV = airway, respiration, ventilation; CR = cardiology; EMT = emergency medical technician; MED = medical; OBGYN = obstetrics and gynecology; OPS = operations; PEDS = pediatrics.

SOURCE: Reprinted, with permission, from the National Registry of Emergency Medical Technicians (NREMT). 2015. Civilian EMT to Military EMT Cognitive Exam Performance. Produced by the NREMT.

through training agreements with civilian trauma centers (e.g., University of Alabama), most of these individuals have no contact with civilian personnel throughout their training, nor do they commonly interact with civilian prehospital providers or civilian medical technicians in their career fields (Cannon, 2016). Furthermore, despite the requirement to function in a high-stress environment (i.e., delivering tactical care under fire) and limited resources, military medics are not required to have had any patient contact prior to deployment (Cannon, 2016). Minimal training and capability requirements for prehospital personnel reflect legacy paradigms for combat casualty care focused heavily on transport of casualties to a hospital. Investigations during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq showed that prehospital care is the phase of care with the greatest potential for reducing deaths from survivable injuries (Eastridge et al., 2012; Kotwal et al., 2011), but this potential is only realized if the medics can perform the interventions necessary to improve outcomes. This conundrum of prehospital training versus real clinical expertise for military medics has been described for many years. Refocusing of military medics away from nonmedical tasks toward actual patient care in a trauma setting is imperative.

Clinical Practice

Following medical education and training, physicians, nurses, and allied health professionals generally are assigned to an MTF. Of the Military Health System’s 56 hospitals and medical centers (DoD, 2014),9 only 6 are either verified by the American College of Surgeons or state-designated as trauma centers:

- Level I—San Antonio Military Medical Center (ACS verified)

- Level II—Walter Reed National Medical Center (ACS verified) and Madigan Army Medical Center (state designated—Washington)

- Level III—Darnall Army Medical Center (state designated—Texas) and Landstuhl Regional Medical Center (ACS verified)10

- Level IV—Tripler Army Medical Center (state designated—Hawaii) (ACS, 2016a; DHB, 2015)

As discussed earlier in this chapter, surgical cases managed within most MTFs bear little resemblance to those faced on the battlefield. In addition,

__________________

9 This number excludes the hundreds of military outpatient facilities that also make up the Military Health System.

10 It should be noted that Landstuhl Regional Medical Center was verified as a Level I center by ACS in 2011. Due to decreased trauma patient volume, the facility voluntarily stepped down to a Level III center, but at any pivot point, could step up to a Level I again.

the Level III and IV centers referenced above provide minimal trauma experience (relative to Level I/II centers) for military medical personnel assigned to them. To maintain adequate caseloads for verification as a Level I center, San Antonio Military Medical Center has a partnership with the local civilian community that enables it to provide care to nonbeneficiary trauma patients (Cannon, 2016). Madigan Army Medical Center in Washington has a similar arrangement that enables it to maintain patient volumes appropriate for a Level II trauma center.

Providers also can be assigned to oversee predeployment training at a civilian trauma center, where injury types and patient clustering better approximate combat casualty scenarios (McCunn et al., 2011). Military personnel assigned to trauma training programs at civilian trauma centers see trauma patients on a daily basis and develop expert-level knowledge, skills, and capabilities. However, if these embedded personnel deploy, it is important that they be replaced with experienced providers so that the training mission of these centers is not compromised.

Predeployment Training and Combat-Relevant Trauma Courses

Given the differing roles of peacetime and deployed military medical providers, the military has developed a number of training mechanisms with the goal of sustaining skills in combat casualty care. These mechanisms include just-in-time training through joint military–civilian predeployment programs and a range of training courses. Periodic, short-term trauma center assignments and the completion of training courses also are part of the military’s continuing education programs.

Joint Military–Civilian Predeployment Training Programs

To address the disparity between the number of military trauma specialists (in all provider categories) and the battlefield requirements for combat casualty care, the majority of military trauma training is outsourced as just-in-time training (2- to 4-week rotations) at five civilian trauma centers (Thorson et al., 2012). In 1996, following the publication of the series of GAO reports referenced above highlighting deficiencies in the military’s ability to maintain the medical readiness necessary to fulfill its wartime mission (GAO, 1992, 1993a,b), Congress mandated that DoD conduct trauma care training in civilian hospitals (GAO, 1998). To comply with this mandate, military medical personnel were permanently assigned to Ben Taub General Hospital, an urban Level I trauma center that treats patients with penetrating injuries whose treatment could prepare trauma teams for the battlefield. Army, Navy, and Air Force surgical teams rotated through Ben Taub on a monthly basis. Over the course of this month-long training

program, military surgeons saw more than twice as many trauma cases as they had in an entire year at their home station. This course resulted in increased confidence among individual providers and the entire trauma team (Schreiber et al., 2002). When the Joint Trauma Training Center at Ben Taub closed, the services opened separate trauma training centers in high-volume civilian facilities (see Table 5-2).

Trauma Courses

A number of trauma training courses are designed to support the readiness of trauma care providers prior to deployment. These courses vary in length, topic area, and training methods (see Table 5-3). Within the military, joint and service-specific courses related to combat casualty care use a combination of didactic and hands-on training methods and have content focused on specific roles of care (prehospital, Role 1, Role 2, etc.) or subspecialties such as orthopedics, emergency medicine, general surgery, anesthesia, and nursing (McManus et al., 2007). Through the Defense Medical Readiness Training Institute (DMRTI), DoD offers 26 jointly sponsored courses with 6 instructor training programs (AMEDD, 2016). DMRTI works with each service and USUHS to develop curriculum and updated content. It is working to streamline readiness training efforts across the services, reduce duplication of training programs, and coordinate readiness training efforts between the military and civilian sectors. DMRTI sponsors the Emergency War Surgery Course and the Tactical Combat Casualty Care Course (Miller, 2015).

Some courses, such as the National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians’ (NAEMT) Prehospital Trauma Life Support and the American

TABLE 5-2 Military–Civilian Predeployment Training Programs

| ARMY | NAVY | AIR FORCE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Program | Army Trauma Training Center | Navy Trauma Team Center | Center for Sustainment of Trauma and Readiness Skills |

| Location | University of Miami Ryder Trauma Center | Los Angeles County Medical Center | Baltimore Shock Trauma, University of Cincinnati, St. Louis University |

| Duration | 14 days | 21 days | 19 days |

| Program highlights | Mass casualty exercise, emphasis on team training | Didactic session, simulation, mass casualty exercise, emphasis on team training for those assigned to Role 2 | Didactic session, simulation, cadaver procedure laboratory, mass casualty exercise |

SOURCE: Thorson et al., 2012.

TABLE 5-3 Combat-Relevant Training Courses Provided by Military and Civilian Organizations

| Course Name | Duration | Provider Type | Topic | Training Methods | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MILITARY | ARMY | Tactical Combat Medical Care | 5 days | Physician assistants, nurse practitioners assigned to Role 2 facilities | Role 2 advanced lifesaving interventions | Live tissue, didactic sessions, and simulation |

| Joint Force Combat Trauma Management Course | 5 days | Combat support hospital care providers | Role 3 training—critical care, patient transport, and operative management | Simulated casualty scenarios using cadaver and live tissue models, and didactic sessions | ||

| JOINT | Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) | 2 days | First responders, including nonmedical personnel | Role 1—TCCC | Casualty scenarios and didactic sessions | |

| Emergency War Surgery Course | 3 days | General and orthopedic surgeons | Various military field topics and surgical skills | Cadaver laboratory and various animal models, mass casualty exercise | ||

| Trauma Outcomes and Performance Improvement Course-Military | 1 day | Physicians, nurses, trauma registrars | Performance improvement | Didactic sessions and military-specific case studies | ||

| CIVILIAN | ACS | Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) | 2–2.5 days | Physicians, physician assistants, advanced practice nurses | Early patient management and resuscitation | Didactic sessions, skill stations |

| Advanced Trauma Operative Management | 1 day | Surgeons | Operative management of penetrating injuries to the chest and abdomen | Didactic sessions, simulated casualty scenarios using cadaver and live tissue models | ||

| Advanced Surgical Skills for Exposure in Trauma | 1 day | Surgeons | Surgical exposures in key areas: neck, chest, abdomen and pelvis, and upper and lower extremities | Didactic sessions, simulated casualty scenarios using cadaver and live tissue models |

| Course Name | Duration | Provider Type | Topic | Training Methods | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIVILIAN | STN | Advanced Trauma Care for Nurses (taught concurrently with ATLS course) | 2–2.5 days | Registered nurses | Management of the multiple-trauma patient | Didactic sessions, skill stations |

| NAEMT | Prehospital Trauma Life Support | 2 days | Emergency medical responders, emergency medical technicians, paramedics, nurses, physician assistants, physicians | Trauma patient management in the prehospital setting | Didactic sessions, skill stations | |

| Tactical Combat Casualty Care for Military Medical Personnel | 2 days | Combat emergency medical services/military personnel, including medics, corpsmen, and pararescue personnel | Trauma patient management on the battlefield in accordance with tactical combat casualty care (TCCC) guidelines | Didactic sessions, skill stations | ||

| Tactical Combat Casualty Care for All Combatants | 1 day | Nonmedical military personnel | Trauma patient management on the battlefield in accordance with TCCC guidelines | Didactic sessions, skill stations |

NOTE: ACS = American College of Surgeons; NAEMT = National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians; STN = Society of Trauma Nurses.

SOURCES: ACS, 2016b; ATRRS, 2016; DMRTI, 2016; Fecura et al., 2008; NAEMT, 2015; STN, 2016.

College of Surgeons’ Advanced Trauma Life Support, were developed in the civilian sector and later adapted for greater relevance to the combat context (DHB, 2015). A notable example is tactical combat casualty care (TCCC), which originated in Special Operations Forces and was expanded to the broader military starting in 2003 (DHB, 2015). It is now the only course that is required as predeployment training prior to being sent into theater (for CENTCOM). TCCC has been broadly adopted for application in the civilian prehospital setting as well, through both the original TCCC

curriculum and a civilian adaptation called tactical emergency casualty care. The Trauma Outcomes and Performance Improvement Course-Military (TOPIC-M) also is noteworthy in that it focuses on educating military medical professionals about quality improvement, a process critical to supporting continuous learning and improvement in a learning trauma care system. Modeled after the Society of Trauma Nurses’ TOPIC course, TOPIC-M breaks down the performance improvement cycle and offers practical strategies for implementing performance improvement initiatives across the echelons of care (Fecura et al., 2008; Fitzpatrick, 2016).

LIMITATIONS OF CURRENT MEDICAL READINESS APPROACHES

The committee observed numerous examples of the deep commitment among medical and health services support personnel from all the services to providing state-of-the-art care to the nation’s wounded service members. The professional excellence and personal dedication of these men and women have yielded transformational advances in trauma care. These accomplishments have been achieved despite a system that often has failed to provide the preparation necessary to meet battlefield casualty care needs. Maintaining a well-trained and adequately staffed military trauma care workforce is crucial given that the volume and degree of trauma found in combat generally will not allow for an on-deployment learning curve (Ramasamy et al., 2010). In the sections below, the committee describes the limitations of current medical readiness approaches.

Inadequate Team Training

The outcome of the multiply injured patient is optimized by the presence of an effective trauma system and multidisciplinary teams. Successfully moving wounded combatants through the five roles of battlefield care requires coordination and teamwork. Excellent communication and team management are crucial to avoiding clinical pitfalls (Bach et al., 2012). As with individuals, there is a team learning curve, and it is helpful to rehearse scenarios as a team before encountering casualties in theater. Pereira and colleagues (2010) demonstrated that during a forward surgical team training exercise at the Army Trauma Training Center, members’ awareness of their role within the team improved from 71 percent to 95 percent, suggesting that functioning as a team during mass casualty training exercises is beneficial. In addition, belief in the ability of the team to function in a trauma scenario improved from 26 percent to 84 percent (Pereira et al., 2010). In a recent survey, respondents overwhelmingly favored team training and supported maintaining team integrity (Schwab, 2015). With few exceptions, however, trauma teams do not train together (especially with

real trauma patients) prior to deployment. The effects of inadequate team training are reflected in that same survey, in which 56.8 percent of respondents indicated that their trauma team was not prepared (Schwab, 2015).

Lack of Standardized and Validated Training Modalities

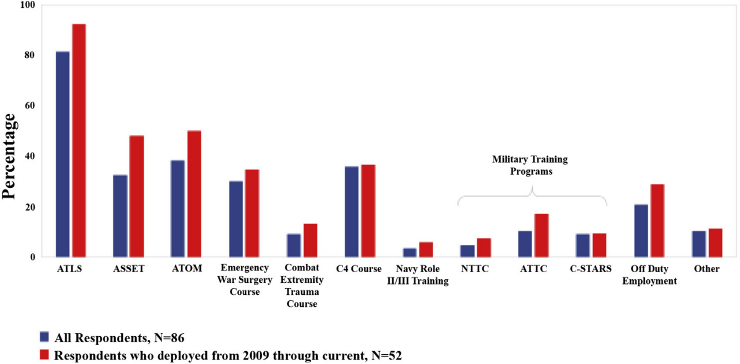

Training is a critical component of a continuous performance improvement cycle, ensuring that advances in knowledge are translated into practice in a timely manner. Successful training requires the development of and adherence to training standards. There is no consistent predeployment training for medical personnel deploying to theater (Rotondo et al., 2011). As described below, the committee found a lack of joint service and role-based standards for trauma training, resulting in variability in the content and utilization of predeployment training courses and programs (see Figure 5-6). Furthermore, although survey data show the perceived benefit of training programs among respondents, the committee is unaware of any data validating the effectiveness of these programs. As a result, military personnel providing care for combat casualties are not universally prepared to deliver optimal care (DHB, 2015). Great potential exists to save lives and decrease disability through a common approach to trauma care readiness training.

Variability Across Military–Civilian Predeployment Training Programs

As shown in Table 5-2, there is significant variation in the scope and duration of the service-specific just-in-time trauma training programs, with no standardized curriculum. Also, these programs are underutilized—very few deploying physicians report undergoing this training. In a recent survey of 137 military surgeons, only 23 percent had attended a Center for Sustainment of Trauma and Readiness Skills (C-STARS), Army Trauma Training Center (ATTC), or Navy Trauma Training Center (NTTC) course, and fewer than half (42 percent) of respondents had attended any predeployment surgical training course prior to their first deployment (Tyler et al., 2012).

While participants praise and value their participation in C-STARS, ATTC, and NTTC training (Tyler et al., 2012), these centers have neither been objectively assessed and verified nor optimized for training, refresher skill enhancement, and team training. Although best practices and innovative methods for teaching have emerged at each site, no formal mechanisms exist for sharing such advances, either among sites or with USUHS and other military training programs (Schwab, 2015). Although conferences, including DoD’s annual research symposium, and peer-reviewed publications offer informal mechanisms for exchanging information, structured

NOTES: These data are from a 2014 survey of 174 military-affiliated members (physicians) of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST). The 28-question survey was approved by the University of Pennsylvania’s institutional review board. One hundred surveys were returned, 86 of which contained complete data for analysis.

ASSET = Advanced Surgical Skills for Exposure in Trauma; ATLS = Advanced Trauma Life Support; ATOM = Advanced Trauma Operative Management; ATTC = Army Trauma Training Center; C-STARS = Center for Sustainment of Trauma and Readiness Skills; NTTC = Navy Trauma Training Center.

SOURCE: Reprinted from Schwab, 2015, with permission from Elsevier.

processes and incentives are needed to promote a collaborative approach to the identification and widespread adoption of best practices in training paradigms. Furthermore, the centers lack consistent expert staffing, a problem exacerbated during those instances in which military trainers have been required to deploy and the centers have been left without a senior military trauma surgeon. The programs also appear to be “out of the mainstream of military medicine and seem poorly valued ‘up the chain of command’” (Schwab, 2015, p. 248). This observation is reflected in the convoluted command structure for each center, which occupies a low position in the hierarchy under each service surgeon general.

Variability in each service’s predeployment training programs often is justified on the basis of differences in mission. However, opportunities exist to harmonize trauma training across the services by reviewing existing programs and standardizing best practices across all centers (DHB, 2015). Several studies have called for the standardization of predeployment training (DuBose et al., 2012; Thorson et al., 2012).

Variability Across Trauma Courses

A number of military and civilian courses are available for development and maintenance of combat casualty care skills. However, course attendance requirements, and in some cases content, are variable. TCCC training is a useful case in point. The experience of the 75th Ranger Regiment (discussed in Chapter 1) demonstrates the value of TCCC in saving lives on the battlefield. The Defense Health Board and the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs have recommended TCCC training, and all of the services have directed that their deploying members obtain such training. However, training in and implementation of TCCC are not consistent or standardized throughout the military (JTS, 2015), as noted in two recent assessments of prehospital trauma care in Afghanistan that documented inconsistent or absent TCCC training among combat forces deployed to CENTCOM (Kotwal et al., 2013; Sauer et al., 2014). A skills sustainment program also is lacking for those who have completed TCCC training in the remote past. The failure to adhere to current TCCC principles and guidelines has resulted in adverse outcomes for casualties (see, e.g., the extremity hemorrhage case in Appendix A). As documented in JTS performance improvement initiatives, these events occurred even in those units that reportedly had been trained in TCCC, as a result of misinformation provided during that training—a reflection of the significant variation in TCCC courses at present (JTS, 2015). The need for standardization is further apparent from recent media reports of providers who were exposed to inappropriate and potentially dangerous training events (JTS, 2015).

The committee also found that best practices in combat casualty care as defined within TCCC and JTS clinical practice guidelines have not been integrated into training courses in a systematic way (Miller, 2015). This represents a major gap in the performance improvement cycle, impeding the reliable transmission of best care practices to clinical providers.

Reliance on Just-in-Time and On-the-Job Training

At the start of Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom, the military medical force was overstaffed with specialists in pediatrics and obstetrics/gynecology but understaffed in specialties critical for combat casualty care. In 2004, the military medical force was short 59 anesthesiologists and 242 general surgeons (Maldon et al., 2015). During the latter years of the wars, additional general surgeons completed trauma and surgical critical care fellowships and deployed to forward areas (Cannon, 2016), but it was still common for nontrauma specialists—for example, specialists in obstetrics/gynecology—to fill in to meet the trauma care needs of forward surgical teams and combat support hospitals

(Maldon et al., 2015; Moran, 2005). Many of these physicians were not appropriately credentialed for the kind of care they were required to deliver and did not receive appropriate predeployment training. It is important to realize that these providers would not be credentialed to care for civilian trauma patients in the United States, but are allowed to care for military trauma casualties when deployed. In effect, the standard of care for trauma patients in the United States was not being met on the battlefield.

From the first year of the war to the last (Chiarelli, 2015), the military’s ability to deliver trauma care showed great variability, due in part to deployed military providers learning on the job rather than entering the combat zone prepared. A survey of military-affiliated physicians, many of whom had experienced multiple deployments, found that more than 50 percent felt that their deployed trauma team was inadequately prepared to operate in the combat environment (Schwab, 2015).

Joint military–civilian training programs such as those offered through ATTC, NTTC, and C-STARS benefit both the civilian and military workforces: they provide some level of skill sustainment for military trauma care providers and augment labor for the civilian center. In addition, they offer opportunities for bidirectional translation of innovative and best practices as embedded military training faculty interface with their civilian colleagues. As an approach to readiness, however, relying on just-in-time training (2-4 weeks) is fundamentally flawed. Outsourced short-duration training just prior to deployment results in teams that have had some exposure to trauma patients, allowing the Military Health System to “check the box” on training, but does not provide the sustained volume of patients required over a longer period of time to ensure an expert level trauma care capability. A short course in trauma, regardless of how excellent, cannot transform a novice into an expert trauma care provider.

Tyler and colleagues (2010) compared the experiences of military surgical residents at civilian trauma centers with the types of surgical cases experienced in theater, and found that the residents could have benefited from further training in injuries and procedures likely to occur in a combat context (e.g., skeletal fixation, genitourinary trauma, and craniotomy). In a recent survey of 246 active duty surgeons deployed at least once in the past decade, 80 percent of respondents indicated they would have liked additional training prior to deployment, particularly in extremity vascular repair (46 percent), neurosurgery (29.9 percent), and orthopedics (28.5 percent) (Tyler et al., 2012). More than a quarter of military surgeons requesting additional experience with general surgery, particularly with mediastinal trauma, vascular injuries, and inferior vena cava and pulmonary trauma (Tyler et al., 2012). Surgeons requested this further training either because they had not been exposed to these types of trauma during their civilian training or because a significant amount of time had passed since they last

treated these types of injuries (Schwab, 2015; Tyler et al., 2012). The lack of competency in combat-relevant skills manifested in suboptimal care on the battlefield and associated preventable morbidity and mortality (see Box 5-2). Martin and colleagues (2009) found that provider competency, particularly related to hemorrhage control, was a factor in 70 percent of preventable deaths.

Variability in Readiness of the Reserves and National Guard

The challenges of sustaining expert-level trauma care skills are magnified in the Reserves and the National Guard. Reservist physicians, nurses, and medics who deploy to combat zones represent a diverse group with respect to both their military background (e.g., recently separated versus no

prior military experience), practice setting, and civilian trauma care experience. In many cases, providers in these positions participate in high-volume, high-acuity clinical care in their civilian practices that readily translates to a high level of deployment readiness and expertise (Cannon, 2016). In one notable case discussed earlier in this chapter, a deployed National Guard unit raised the standard of care for MEDEVAC units when comparatively better outcomes were observed in patients transported by the National Guard CCFP-certified medics (Mabry et al., 2012), prompting efforts to align the military’s hospital evacuation policies with the civilian medical standard (Ficke et al., 2012).

Like their active duty counterparts, some reservists and National Guard members deploy from a busy trauma practice, but many others have seen few trauma patients (DuBose et al., 2012). For the latter, the lack of stan-

dardized predeployment training requirements results in variable levels of readiness. For surgeons, for example, the minimum criterion for deployment is completion of a general surgery residency, and their deployment station in theater generally is not dependent on their civilian practice. Army general surgeon reservists deploy to theater directly from the Replacement Center at Fort Benning, Georgia, where they receive very generalized predeployment training (e.g., weapons, equipment, cultural preparation). Air Force predeployment requirements include the Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) and Emergency War Surgery courses, as well as knowledge of JTS clinical practice guidelines. All deploying Air Force reservists must be involved regularly in civilian trauma care or undergo predeployment training at a C-STARS site. The deployment requirements for Navy reservists include a combat casualty care course and in some cases training at the Naval Trauma Training Center at Los Angeles County Hospital (DuBose et al., 2012). Issues of predeployment training for reservists and National Guard members will only become more pressing as the military increasingly relies on these part-time service members to sustain a ready and effective force in times of fiscal austerity.

Gaps in Leadership Education, Awareness, and Accountability

Under Title 10 of the United States Code, the services are responsible for training and equipping the personnel that will be assigned to a geographic combatant command to meet wartime medical support needs. Once medical forces are delivered in theater, line leadership within the combatant command is responsible for the execution of the theater trauma system, including the quality of care delivered by the trauma workforce. To assume this responsibility effectively, line leaders and the unit surgeons11 (e.g., battalion surgeons) that advise them require a thorough understanding of the fundamentals of combat casualty care, trauma systems, and their tactical relevance (DHB, 2015). Officer and enlisted leadership courses attended by senior line and medical leaders, however, do not provide education and training on trauma system concepts, resulting in a lack of understanding of military trauma care and the importance of sustaining and continuously improving the military trauma system by those who are ultimately accountable for the quality of the system (Mullen, 2015).

As discussed in Chapter 1, the concept of preventable death after injury and key aspects of tactical medicine were incorporated into all com-

__________________

11 Contrary to the name, unit surgeons generally are not trained surgeons but typically are generalists (e.g., primary care physicians). In theater, they are responsible for sick call, light trauma care, and providing medical advice to the unit leadership (DHB, 2015; Sorbero et al., 2013).

mand training and education programs as a critical element of the Israel Defense Force’s initiative to eliminate preventable death on the battlefield (Glassberg et al., 2014). The casualty response system of the 75th Ranger Regiment, which tracked first responders’ training achievement, is an exemplary model (DHB, 2015), but the committee found no evidence that this level of line leadership accountability is widespread across DoD. Outside of the Special Operations Command, a tracking system that provides line leaders with visibility on predeployment trauma training would require support from the service surgeons general and the Defense Health Agency.

WORKFORCE OPPORTUNITIES TO FACILITATE BIDIRECTIONAL EXCHANGE OF TRAUMA CARE INNOVATIONS AND BEST PRACTICES

Historically, the exchange of innovations and best practices between the military and civilian sectors has been informal, based on individuals practicing in both realms and professional meetings where members of the two communities have shared knowledge and ideas. Military trauma professionals returning to civilian practice have brought wartime lessons and practices with them. During the Afghanistan and Iraq wars, a formalized program to facilitate the exchange of trauma care knowledge and experience—the Senior Visiting Surgeon Program (described in Chapter 4) was established, but there remains a lack of robust collaboration between the two sectors, except in the few civilian trauma centers with assigned military personnel or recently retired or separated personnel. Although many military physicians are trained in civilian academic medical centers, they have little exposure to civilian physicians or practice once they enter military practice. In addition, there are financial and policy barriers to military participation in academic conferences and restrictions on the military’s use of civilian consultants (Cannon, 2016).

Numerous opportunities exist in both education and practice to improve collaboration and promote dissemination of lessons learned and best practices across the military and civilian sectors (see Appendix C). For example, rotations of military residents through civilian trauma centers could be increased, or all combat-deployable personnel (physicians, nurses, and medics) could be required to routinely practice in civilian trauma centers. Building on the model of the Senior Visiting Surgeon Program, regular opportunities for civilians (beyond just surgeons) to practice temporarily in military trauma centers during wartime could be considered, as could the establishment of joint military–civilian programs to facilitate collaborative approaches to addressing high-priority challenges and developing best practice models (Richmond, 2016).

Similar opportunities exist to promote the exchange of lessons learned and best practices in prehospital trauma care between the military and civilian sectors. However, structural barriers make it challenging to exploit these opportunities. As with other medical licensure and certification, states regulate the scopes of practice for prehospital EMS providers (NHTSA, 2007). State scopes of practice vary not only from state to state but also at the local level, making the opportunity for military medics to practice critical skills in the civilian sector dependent upon state and local requirements and protocols. Moreover, prehospital military trauma care is often more advanced than what civilian EMS protocols allow, making it challenging for medics to practice their skills in the civilian sector and limiting bidirectional sharing of knowledge (Rodriguez, 2015). For example, pain medications (e.g., trans-oral fentanyl, ketamine) are routinely administered by military medics in the prehospital environment in theater to minimize pain and reduce risk of post-injury mental health sequelae. However, providing these medications in a civilian hospital (or even a military one) in the United States, even under physician guidance, is considered outside their scope of practice and is thus not permitted, even for training purposes (Cannon, 2016). These challenges could be overcome through clinical learning agreements and system approaches whereby military medics could practice with civilian EMS personnel in the prehospital setting, while also participating in in-hospital trauma team training in emergency departments and operating suites, where they could gain experience with the specific skills required for military trauma care. States also could consider permitting military medics to exercise trauma skills not normally associated with EMTs under the guidance and precepting of a civilian paramedic. At the same time, military medics often have more limited exposure to treating civilian medical conditions (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, stroke), and state and local issues limit their movement directly into civilian EMS positions when they return from military service. National-, state-, and local-level programs are emerging to generate a pathway for this transition (FICEMS, 2013; McCallion, 2013).

At the national level, the translation of prehospital lessons learned from the military to the civilian sector is challenging, even cumbersome. Changes in civilian practice could be incorporated through states’ certification requirements, which are driven largely by the National Registry for EMTs; however, National Registry recertification operates on a 2-year cycle, limiting rapid translation through this mechanism (Rodriguez, 2015). More rapid changes in clinical practice are dependent on local or state EMS system leadership. Within the civilian sector, local (and even state) EMS systems monitor national and organizational evidence-based guidelines so they can make changes to their own protocols accordingly, with corresponding continuing education for providers.

The incorporation of civilian prehospital trauma practices into military care is even less structured and refined. The overall paucity of prehospital research applies to prehospital trauma research. The national variation in EMS and trauma systems is an additional limitation. Even among the best trauma systems, prehospital trauma care varies based on the system’s components, structure, protocols, and degree of integration of EMS. This variation makes the identification and generalization of best practices challenging even within the civilian sector, much less across the military and civilian sectors.

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS

CONCLUSION: To eliminate preventable mortality and morbidity at the start of and throughout future conflicts, comprehensive trauma training, education, and sustainment programs throughout DoD are needed for battlefield-critical physicians, nurses, medics, administrators, and other allied health professionals who comprise military trauma teams. This effort will ensure that a ready military medical force with expert combat casualty care skills is sustained throughout peacetime. A single military leader (general officer) needs to be accountable for generating and sustaining this education and training platform across the Military Health System to deliver trauma experts to the battlefield. In addition, line and medical leaders need to be held accountable for the results delivered by their trauma teams on the battlefield.

Related findings:

- A number of policy and operational barriers—including an oscillating trauma workload, providers’ beneficiary care responsibilities, and recruitment and retention challenges in the absence of defined trauma care career paths—impede the military’s ability to ensure an expert trauma care workforce.

- DoD lacks validated, standardized training and skill sustainment programs.

- The military’s reliance on just-in-time (e.g., trauma courses, short-duration predeployment training programs at civilian trauma centers) and on-the-job (i.e., on-deployment) training does not provide the experience necessary to ensure an expert trauma care workforce.

- Officer and enlisted leadership courses attended by senior line and medical leaders do not provide education and training on trauma system concepts, resulting in a lack of understanding of military trauma care by those who are responsible for the execution of the theater trauma system.

REFERENCES

ACS (American College of Surgeons). 2014. Resources for optimal care of the injured patient. Chicago, IL: ACS.

ACS. 2016a. Searching for verified trauma centers. https://www.facs.org/search/trauma-centers? (accessed February 26, 2016).

ACS. 2016b. Trauma education. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/trauma/education (accessed May 10, 2016).

AMEDD (U.S. Army Medical Department). 2016. Defense Medical Readiness Training Institute (DMRTI). http://www.cs.amedd.army.mil/dmrti.aspx (accessed February 26, 2016).

ASAHP (Association of Schools of Allied Health Professions). 2014. Who are allied health professionals? http://www.asahp.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Health-Professions-Facts.pdf (accessed February 26, 2016).

ATRRS (Army Training Requirements and Resources System). 2016. Search the ATRRS course catalog. https://www.atrrs.army.mil/atrrscc/search.aspx?newsearch=true (accessed May 10, 2016).

Bach, J., J. Leskovan, T. Scharschmidt, C. Boulger, T. Papadimos, S. Russell, D. Bahner, and S. Stawicki. 2012. Multidisciplinary approach to multi-trauma patient with orthopedic injuries: The right team at the right time. OPUS 12 Scientist 6(1):6-10.

Beekley, A. C. 2015. Preparing the next generation of combat surgeons. Paper presented to the Committee on Military Trauma Care’s Learning Health System and Its Translation to the Civilian Sector, Meeting Two, July 23-24, Washington, DC.

Benner, P. 1982. From novice to expert. American Journal of Nursing 82(3):402-407.

Bier, S., E. Hermstad, C. Trollman, and M. Holt. 2012. Education and experience of Army flight medics in Iraq and Afghanistan. Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine 83(10):991-994.

Bridges, E. 2016. Nursing in the context of a learning trauma care system. Paper presented to the Committee on Military Trauma Care’s Learning Health System and Its Translation to the Civilian Sector, January 15, Washington, DC.

Cannon, J. W. 2016. Military–civilian exchange of knowledge and practices in trauma care. Paper commissioned by the Committee on Military Trauma Care’s Learning Health System and Its Translation to the Civilian Sector. nationalacademies.org/TraumaCare.

Cap, A. P. 2015. Mission planning. Paper presented to the Committee on Military Trauma Care’s Learning Health System and Its Translation to the Civilian Sector, Meeting One, May 18-19, Washington, DC.

Chiarelli, P. W. 2015. MCRMC health care recommendations summary. Paper presented to the Committee on Military Trauma Care’s Learning Health System and Its Translation to the Civilian Sector, Meeting Two, July 23-24, Washington, DC.

Cothren, C. C., E. E. Moore, and D. B. Hoyt. 2008. The U.S. trauma surgeon’s current scope of practice: Can we deliver acute care surgery? Journal of Trauma 64(4):955-965.

DHB (Defense Health Board). 2015. Combat trauma lessons learned from military operations of 2001-2013. Falls Church, VA: DHB.

DMRTI (Defense Medical Readiness Training Institute). 2016. Courses. http://www.dmrti.army.mil/courses.html (accessed May 20, 2016).

DoD (U.S. Department of Defense). 2014. Military Health System review: Final report to the Secretary of Defense. Washington, DC: DoD.

DoD. 2015a. Evaluation of the TRICARE program: Access, cost, and quality: Fiscal year 2015 report to Congress. Washington, DC: DoD.

DoD. 2015b. Personnel procurement: Army medical department professional filler system, Army regulation 601-142. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Army, DoD.

Dreyfus, S. E. 1981. Formal models vs. human situational understanding: Inherent limitations on the modeling of business expertise. Berkeley: University of California.

Dreyfus, S. E., and H. L. Dreyfus. 1980. A five-stage model of the mental activities involved in directed skill acquisition. Berkeley: University of California.

DuBose, J., C. Rodriguez, M. Martin, T. Nunez, W. Dorlac, D. King, M. Schreiber, G. Vercruysse, H. Tien, A. Brooks, N. Tai, M. Midwinter, B. Eastridge, J. Holcomb, B. Pruitt, and Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma Military Ad Hoc Committee. 2012. Preparing the surgeon for war: Present practices of US, UK, and Canadian militaries and future directions for the US military. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 73(6 Suppl. 5):S423-S430.