8 A Vision for a National Trauma Care System

The committee was tasked with recommending how trauma care advances from the last decade of war in Afghanistan and Iraq can be sustained and built upon to ensure readiness for the military’s next combat engagement, and how lessons learned by the military can be better translated to the civilian sector. In the course of this study, it became clear that these two objectives are inextricably linked and can best be achieved through a systematic and coordinated approach. This chapter presents the committee’s recommendations for a national trauma care system that would simultaneously support a ready military trauma care capability and establish systematic processes for the transfer of knowledge between the military and civilian sectors.

THE NEED FOR COORDINATED MILITARY AND CIVILIAN TRAUMA CARE SYSTEMS

Trauma care in the military and civilian sectors is a portrait of contradiction—lethal contradiction. In the military setting, survival rates of service members injured in war over the past 50 years have improved dramatically and nearly continuously (Pruitt and Rasmussen, 2014). Much of this gain has come from new approaches to trauma care, both managerial and clinical. Important breakthroughs have included, for example, refinement of the tiered system of evacuation from the point of injury to definitive treatment in a major center, new approaches to fluid management, effective prehospital combat casualty care training and control of hemorrhage, iterative knowledge growth resulting from the communication

and review procedures of the Joint Trauma System (JTS), deployment of sound clinical guidelines, and limited but effective use of clinical registries (Eastridge et al., 2006, 2009). Such improvements in military trauma care appear, in retrospect, to be due in large measure to the use of effective approaches to learning coupled with a bias toward rapid, but disciplined, cycles of inference and testing in the field, which the military terms “focused empiricism” (see Chapter 4) (Elster et al., 2013a,b).

Many of these cultural and systemic attributes of military trauma care mirror those of a learning health system as described within the Institute of Medicine (IOM, 2013) report Best Care at Lower Cost. In fact, the learning processes in the military preceded that report’s articulation of a learning system by many years. However, the committee found that although many of the individual components of a learning system are in place, the full potential of such a system is not being realized in either the military or the civilian sector, and the contradiction between excellence and striking results in pockets of military and civilian trauma care on the one hand and gaps in consistency, clarity, and leadership on the other has deadly implications. Thousands or more lives could likely be saved over the course of future wars if military trauma care were improved (Eastridge et al., 2012). That potential gain soars into the tens of thousands of lives if similar improvements could be achieved in civilian trauma care (Hashmi et al., 2016), given that civilian trauma deaths numerically dwarf military combat deaths.

Gaps in the military and civilian trauma care systems include the following:

- Lessons learned by U.S. military personnel that improve the care and recovery of service members injured on the battlefield have been neither thoroughly nor adequately disseminated throughout the military, nor have they been translated reliably into civilian trauma care. The result has been many thousands of instances of preventable death and needless disability across the two sectors, along with excessive costs.

- Effective components of the military’s learning trauma care system—most notably registries, research, and the JTS—lack sustained commitment and ongoing support, and therefore are degrading and could even disappear at any time.

- Experience shows that many of the hard-earned improvements in trauma care techniques and skills achieved during wartime are lost during the periods between wars. The result is needless mortality and morbidity during the “relearning” period in the early phases of new conflicts.

- In neither the military nor the civilian setting is documentation of

-

care across the trauma care continuum adequate, from the point of injury through rehabilitation, recovery, and reintegration. This gap compromises the care of individuals and impedes learning by caregivers in the pursuit of improved trauma care and outcomes.

- The continuum of care for service members may ultimately span the military and civilian (i.e., the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs [VA]) sectors. Inadequate bidirectional sharing of trauma patient data (including long-term outcome data) between the Military Health System and the Veterans Health Administration care system compromises the care of individuals who transition between those systems (Maldon et al., 2015) and impedes learning and continuous improvement.

- Within the present military command structure, authority, responsibility, “ownership,” and accountability for combat casualty care are fragmented and this fragmentation can seriously compromise care of the wounded. Key decision makers in the line of command lack the knowledge, skills, clarity of responsibility, and perspective to address problems in the trauma care system.

- Presently, most military trauma care teams are not ready to provide the highest-quality care to wounded service members. The existing training and deployment system is incapable of providing readiness for the best possible trauma care in future conflicts, and current levels of readiness are decreasing over time.

- Civilian capabilities to care for trauma patients, both on an everyday basis and during mass casualty incidents, are geographically uneven and largely inadequate. After a serious injury, disaster, or terrorist attack, where one lives may determine whether one lives.

- Current levels of investment in research to improve trauma care and rehabilitation are not commensurate with the societal burden of trauma. Although this has been known for decades, political and administrative barriers and the absence of effective advocacy groups perpetuate this unwise imbalance.

Without major corrective action to address these gaps on the part of numerous stakeholders, especially the highest levels of civilian and military leadership in the United States, tens of thousands of injured service members and civilians will lose lives and limbs that could have been saved. The committee takes as its beacon the accomplishments of the 75th Ranger Regiment, a U.S. Army Special Operations Force. Driven by the vision and action of its commanding officer, this regiment implemented a learning trauma care system that led to unprecedented results, driving the rate of preventable trauma deaths close to zero even under dangerous and austere conditions (Kotwal et al., 2011).

Improvements in all of the above deficiencies will require two significant changes: (1) an entirely new level of competent, committed leadership for trauma care in the military command structure, and (2) an unprecedented and redesigned collaboration between military and civilian trauma care providers and systems. This imperative resonates most strongly with respect to the key military mission of “readiness”—the requirement that the capabilities of military trauma care, including but not limited to the supply of expert clinicians and teams, be available to support combatant commands as needed, where needed, and when needed at all times. Combat readiness of military trauma care cannot be achieved within the current structures of training and workforce support.

Some significant improvements in military trauma care and learning can be achieved within the military sector alone, especially with more thorough engagement of combatant commanders similar to that exemplified by 75th Ranger Regiment, the standardization of best practices across all commands, and uniform data collection. However, it is neither feasible nor, in the face of the evidence, rational to attempt to address the deficiencies in military trauma care and learning more broadly without extending change efforts to encompass the civilian trauma system and the relationships between military and civilian trauma care in the areas of leadership, research, guidelines and standards, registry use, workforce training, and the regional roles of trauma centers. Military and civilian trauma care and learning will be optimized together, or not at all.

Conclusion: A national strategy and joint military and civilian approach for improving trauma care is lacking, placing lives unnecessarily at risk. A unified effort is needed to address this gap and ensure the delivery of optimal trauma care to save the lives of Americans injured within the United States and on the battlefield.

A VISION FOR A NATIONAL TRAUMA CARE SYSTEM

Given the significant burden of traumatic injury, it is in the nation’s best interest to implement a new collaborative paradigm between military and civilian trauma systems, thus ensuring that the lessons learned over the course of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq are not lost. Though tenuous, there now exists a military trauma system built on a learning system framework and an organized civilian trauma system well positioned to assimilate the recent wartime trauma lessons learned and to serve as a repository and incubator for innovation in trauma care during interwar periods. Together, these developments provide opportunities to systematically integrate military and civilian efforts aimed at improving trauma care and eliminating preventable deaths after injury—whether the trauma occurs on the battle-

field or within the United States. This integration would not only ensure trauma expertise within the military is sustained and improved, but also would galvanize continuous bidirectional learning. To that end, the committee believes a national strategy for trauma care—one that describes an integrated civilian and military approach—is needed to drive the coordination and continuous improvement of our nation’s trauma care capability. The potential benefits are clear: the first casualties of the next war would experience better outcomes than the casualties of the last war, and all civilians would benefit from the hard-won lessons learned on the battlefield.

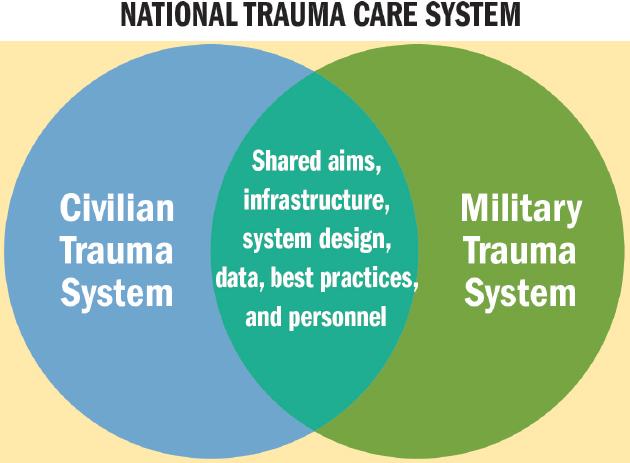

A national trauma care system would need to be grounded in sound learning health system principles (IOM, 2013) applied across the full continuum of care, from point of injury to definitive care, rehabilitation, and beyond. Success will require the development of a systems approach within and between the military and civilian sectors that synergizes the efforts of both and ensures the continuous bidirectional exchange of lessons learned, best practices, personnel, and data (see Figure 8-1). To achieve optimal integration, this approach must be informed by a complete evaluation of capabilities, education, system design, team qualities, gaps, and inhibitory factors in each domain. Properly linked—through shared aims, common standards, an integrated framework, clear lines of knowledge transfer, and shared points of accountability—the two systems would improve trauma outcomes and advance innovation through a unified effort. For maximum

impact, such an effort would need to interface with national injury prevention efforts at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, national preparedness efforts, and the broad range of White House-led initiatives around service member and veterans mental health (see Box 7-8 in Chapter 7).

Importantly, this national approach is consistent with the nation’s efforts to reform the health care delivery system and warrants inclusion as an explicit component of those efforts. Many of the challenges discussed in this report—such as fragmentation across the continuum of care and ensuring the delivery of quality care—are not specific to trauma. In addition, a trauma system both relies upon and participates in the overall health care delivery system, from prevention to acute care and rehabilitation; as such, it is important that the established national trauma care system is integrated with the larger delivery system. Standards, measures and incentives (e.g., those developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS] and the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology [ONC]) currently applied to other fields of medicine also need to be applied to trauma care. With such integration, the improvements in trauma care delivery envisioned by the committee may also strengthen the health delivery system more generally. For example, integrating acute and long-term care systems will not only improve the transitions of care for trauma patients but may also create efficiencies and second-order effects (i.e., halo effect) for other emergent, time-sensitive conditions (Utter et al., 2006). Yet, trauma care is also distinct in that it extends beyond health care to interface with public health, public safety, and emergency management. Thus, a national approach to trauma care also further readies our civilian trauma and emergency response systems for disasters and other mass casualty incidents.

The benefits of a national trauma care system are myriad (see Box 8-1). Underpinning this proposed national system is the expectation that the military and civilian trauma systems would work seamlessly together toward optimal outcomes, which this committee defines as zero preventable deaths after injury and the pursuit of the best possible recovery for trauma survivors. Achieving this vision will require committed leadership from the military and civilian sectors and a joint framework for learning to advance trauma care.

THE ROLE OF LEADERSHIP

Neither high-functioning complex care systems nor active and agile learning systems can thrive without strong, dedicated, and continuous expert leadership. Good-hearted volunteerism is important but not enough. In Chapters 4-7, military and civilian trauma systems are examined through the lens of a learning health system. The discussion in those chapters reveals that although many of the components of a learning system are in place,

the full potential of such a system is not being realized in either sector. In many cases, shortfalls stem not from technical barriers but from a deficiency of leadership will.

National-Level Leadership

Currently, military trauma data, education and training, systems design, and performance improvement activities remain largely isolated from their civilian counterparts. Despite the interdependence of the civilian and military trauma care systems, no sufficient national effort exists to improve coordination and synergy between them. There is no common leadership structure with influence over policy in the military and civilian sectors, and leaders from the stakeholder federal agencies have inadequate incentives to work collaboratively toward a national approach to trauma care delivery. As a result, the United States lacks a unified, cohesive vision and comprehensive strategy and regulatory framework for ensuring the delivery of optimal care for injured patients.

Conclusion: Despite the tremendous societal burden of trauma, the absence of a unified authority to encourage coordination, collaboration, and alignment across and within the military and civilian sectors has led to variation in practice, suboptimal outcomes for injured patients, and a lack of national attention and resources directed toward trauma care.

To eliminate the 20,000-30,000 preventable deaths after injury that occur annually in the United States (Hashmi et al., 2016; Kwon et al., 2014) and to ensure a national trauma response capability for all intentional and unintentional mass casualty incidents, high-level executive branch leadership will be needed in catalyzing processes for improving civilian trauma care and the exchange of trauma care knowledge between the military and civilian sectors. One key step would be for a presidentially authorized body or process to declare national aims for improving the processes and outcomes of trauma care, and then to support the convening, planning, and monitoring efforts necessary to achieve those aims.

Recommendation 1: The White House should set a national aim of achieving zero preventable deaths after injury and minimizing trauma-related disability.

Recommendation 2: The White House should lead the integration of military and civilian trauma care to establish a national trauma care system. This initiative would include assigning a locus of accountability

and responsibility that would ensure the development of common best practices, data standards, research, and workflow across the continuum of trauma care.

To achieve the national aim (Recommendation 1), the White House should take responsibility for

- creating a national trauma system comprising all characteristics of a learning organization as described by the IOM;

- convening federal agencies (including the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the U.S. Department of Transportation, the VA, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, and the U.S. Department of Defense) and other governmental, academic, and private-sector stakeholders to agree on the aims, design, and governance of a national trauma care system capable of continuous learning and improvement;

- establishing accountability for the system;

- ensuring appropriate funding to develop and support the system;

- ensuring the development of a data-driven research agenda and its execution;

- ensuring the reduction of regulatory and legal barriers to system implementation and success;

- ensuring that the system is capable of responding domestically to any (intentional or unintentional) mass casualty incident; and

- strategically communicating the value of a national trauma care system.

Military Leadership

Military trauma care has made substantial advances, but the committee found that many of these advances have occurred not because of formal leadership, but despite the absence of clear leadership. The military has no unified medical command, no single senior military medical leader, directorate, or division solely responsible for combat casualty care. Combatant commanders responsible for the delivery of care on the battlefield rely on the services to provide a ready medical force, but lack a clear understanding of that process and its current deficiencies, as well as any mechanism for accountability. To carry out their responsibilities, it is necessary for military leadership to receive education and training on trauma system components and the importance of sustaining and improving the military trauma system.

Overall, DoD’s existing trauma care system and resources (1) are not aligned with or accountable to a specific Defense Health Agency leader

in support of the combat support agency mission, (2) lack consistency in training and practice across the services and combatant commands, and (3) fail to hold service and line leadership accountable for the standards of medical care provided and for combat casualty care outcomes. The result is a military trauma care system that functions largely independently from line understanding and without the stability, standardization, and resources that would allow it to deliver on the nation’s promise to its men and women sent into combat: that the trauma care they receive will be the best in the world, regardless of when and where they are injured—in short, that preventable deaths after injury from combat and military service will be avoided, from the first to the last casualty.

Conclusion: Given current structures and diffusion of authority within DoD, the Military Health System and the line commands are not able to ensure and maintain trauma care readiness in peacetime, ensure rapid transfer of best trauma care knowledge across DoD commands or between the military and civilian sectors, or ensure the availability of the infrastructure needed to support a learning trauma care system.

DoD could solve some of these leadership problems on its own initiative by clarifying doctrine and establishing stronger lines of responsibility and authority, especially between the line leadership and the Military Health System. This task appropriately would fall to the Secretary of Defense as the only executive in the chain of command with oversight over the Secretaries of the military departments, the combatant commanders, the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs, and the Defense Health Agency. However, the major challenges to the readiness mission cannot be solved within DoD alone, but will require expanding existing relationships and developing new ones with civilian trauma systems at the national and regional levels.

Recommendation 3: The Secretary of Defense should ensure combatant commanders and the Defense Health Agency (DHA) Director are responsible and held accountable for the integrity and quality of the execution of the trauma care system in support of the aim of zero preventable deaths after injury and minimizing disability. To this end

- The Secretary of Defense also should ensure the DHA Director has the responsibility and authority and is held accountable for defining the capabilities necessary to meet the requirements specified by the combatant commanders with regard to expert combat casualty care personnel and system support infrastructure.

- The Secretary of Defense should hold the Secretaries of the military departments accountable for fully supporting DHA in that mission.

- The Secretary of Defense should direct the DHA Director to expand and stabilize long-term support for the Joint Trauma System so its functionality can be improved and utilized across all combatant commands, giving actors in the system access to timely evidence, data, educational opportunities, research, and performance improvement activities.

To meet the needs of the combatant commanders, the accountable DHA leader should sustain and fund elements of a learning trauma care system that are performing well within DoD, and better align efforts that today are fragmented or insufficiently supported. Steps to take to these ends include

- developing policies to support and foster effective engagement in the national learning trauma care system;

- integrating existing elements of a learning system into a national trauma care system;

- maintaining and monitoring trauma care readiness for combat and, when needed, for domestic response to mass casualty incidents;

- continuously surveying, adopting, improving and, as needed, creating novel best trauma care practices, and ensuring their consistent implementation across combatant commands;

- supporting systems-based and patient-centered trauma care research;

- ensuring integration across DoD and, where appropriate, with the VA, for joint approaches to trauma care and development of a unified learning trauma care system;

- arranging for the development of performance metrics for trauma care, including metrics for variation in care, patient engagement/satisfaction, preventable deaths, morbidity, and mortality; and

- demonstrating the effectiveness of the learning trauma care system by each year diffusing across the entire system one or two deeply evidence-based interventions (such as tourniquets) known to improve the quality of trauma care.

As noted in a previous evaluation of the Joint Trauma System, through the JTS,

America has demonstrated its commitment to provide state of the art care for wounded warriors and expects that the system will achieve optimal outcomes. Therefore, the JTS and all future Joint Theater Trauma Systems [JTTSs] must continue to be immediately responsive, adaptable, and fully capable of achieving this mission in all aspects of U.S. military combat, humanitarian, and other contingency operations. To accomplish this, a

highly sophisticated enduring system must continue to be refined and supported during times of peace and of war. (Rotondo et al., 2011, p. 6)

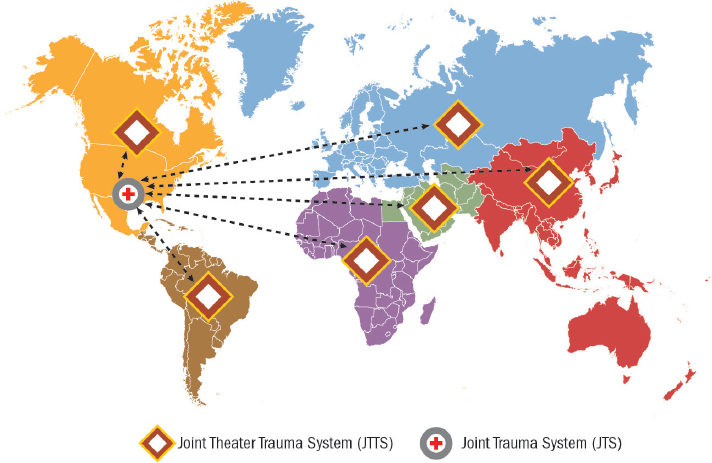

Further institutionalization of the JTS is needed to ensure that the best practices, lessons learned, and systems proven successful in one combatant command (e.g., U.S. Central Command [CENTCOM] Joint Theater Trauma System) will be disseminated and applied at the system level across DoD, in any theater in which the military might be deployed and expected to deliver expert trauma care (see Figure 8-2). Beyond this needed standardization, there may be value in further expanding the mission of the JTS to include trauma system design and planning for future combat operations in different areas of operation (Ediger, 2016). During the interwar period, the JTS could function and hone its mission by reviewing and managing the thousands of nonbattle injuries that are seen every year within the Military Health System. This experience would enable the JTS to be ready when combat operations develop.

NOTES: Different colored regions on the map represent individual geographic combatant commands. U.S. Central Command, for example, is colored green. Arrows between each JTTS and the JTS are double headed to indicate the importance of bidirectional information sharing. As best practices and lessons learned are identified within a JTTS, they should be shared with the JTS and from that central body disseminated as appropriate to all other JTTSs.

Civilian-Sector Leadership

As difficult as clarifying responsibility and authority for trauma care and readiness may be in the military, it is even more challenging in the civilian sector, where leadership has been left mainly to states, counties, and municipalities, with little federal oversight to ensure national goals or consistent practices. No single federal entity is accountable for the full continuum of trauma capabilities in the United States. At the federal and national level, coordinating bodies and processes are fragmented and severely underresourced for the magnitude of the task.

Conclusion: The lack of formal, funded mechanisms for coordination, communication, and translation has led to inefficiency and variation across the civilian sector in clinical care practices, education and training, research efforts, and continuous performance improvement. Collectively, these deficiencies have contributed to suboptimal outcomes for injured patients in the United States and tens of thousands of preventable deaths after injury each year.

Efforts parallel to those recommended above for DoD are needed in the civilian sector, led by HHS. The committee recommends HHS as the lead actor based on its conviction that the improvement and optimization of civilian trauma systems spanning the continuum of care can be accomplished only if the entire system is organized within a framework of health care delivery. Trauma care is unquestionably linked to the arenas of public safety and emergency management, and DHS and DOT both are important stakeholders engaged in trauma and emergency care; however, their foci are too narrow to encompass trauma care in its entirety. As the agency responsible for the nation’s public health and medical care, HHS can provide accountability and drive needed improvements in system-wide communication, data collection and sharing, and quality of care, but it is important for this to be accomplished through a coordinated effort that engages the other federal, private, and professional society stakeholders.

Recommendation 4: The Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) should designate and fully support a locus of responsibility and authority within HHS for leading a sustained effort to achieve the national aim of zero preventable deaths after injury and minimizing disability. This leadership role should include coordination with governmental (federal, state, and local), academic, and private-sector partners and should address care from the point of injury to rehabilitation and post-acute care.

The designated locus of responsibility and authority within HHS should be empowered and held accountable for

- convening a consortium of federal (including HHS, DOT, the VA, DHS, and DoD) and other governmental, academic, and private-sector stakeholders, including trauma patient representatives (survivors and family members), to jointly define a framework for the recommended national trauma care system, including the designation of stakeholder roles and responsibilities, authorities, and accountabilities;

- developing a national approach to improving care for trauma patients, to include standards of care and competencies for prehospital and hospital-based care;

- ensuring that trauma care is included in health care delivery reform efforts;

- developing policies and incentives, defining and addressing gaps, resourcing solutions, and creating regulatory and information technology frameworks as necessary to support a national trauma care system of systems committed to continuous learning and improvement;

- developing and implementing guidelines for establishment of the appropriate number, level, and location of trauma care centers within a region based on the needs of the population;

- improving and maintaining trauma care readiness for any (intentional or unintentional) mass casualty incident, using associated readiness metrics;

- ensuring appropriate levels of systems-based and patient-centered trauma care research;

- developing trauma care outcome metrics, including metrics for variation in care, patient engagement/satisfaction, preventable deaths, morbidity, and mortality; and

- demonstrating the effectiveness of the learning trauma care system by each year diffusing across the entire system one or two deeply evidence-based interventions (such as tourniquets) known to improve the quality of trauma care.

Demonstrating System Effectiveness

The measure of a learning system’s effectiveness is whether it is capable of supporting broad, rapid, meaningful change in practice. Accordingly, as directed in Recommendations 3 and 4, military and civilian stakeholders should commit to diffusing specific improvements in trauma care (e.g., broad availability of tourniquets or reliable application of a key trauma

response protocol) every year throughout the system, and setting explicit, numeric aims for their adoption within aggressive time frames (e.g., within 6 months or 1 year). Diffusing straightforward, evidence-based practices—or attempting to do so—would test whether the learning trauma care system actually has value and impact, serve to highlight its deficiencies, and support its improvement. If successful, such efforts also could build confidence in the system among key actors (e.g., clinicians, medics) and increase its use. The absence of a process for ensuring that newly recommended technologies, techniques, and therapeutics reach combat casualty care providers in a reliable and timely way has been identified as a critical gap within DoD (Butler et al., 2015).

While significant improvements to the learning system for trauma care are required, a complete redesign of the entire system (with all the consensus building and resource mobilization entailed) will not be accomplished overnight. Yet the urgent need to avoid preventable deaths after injury demands concomitantly urgent action. It is by no means wise or necessary to wait for a full redesign of the system before taking action. Setting aims for the near term would be an efficient way to drive broad and needed improvement now. A beneficial by-product would be immediate continuous innovation in the learning system generated in pursuit of such aims.

AN INTEGRATED MILITARY–CIVILIAN FRAMEWORK FOR LEARNING TO ADVANCE TRAUMA CARE

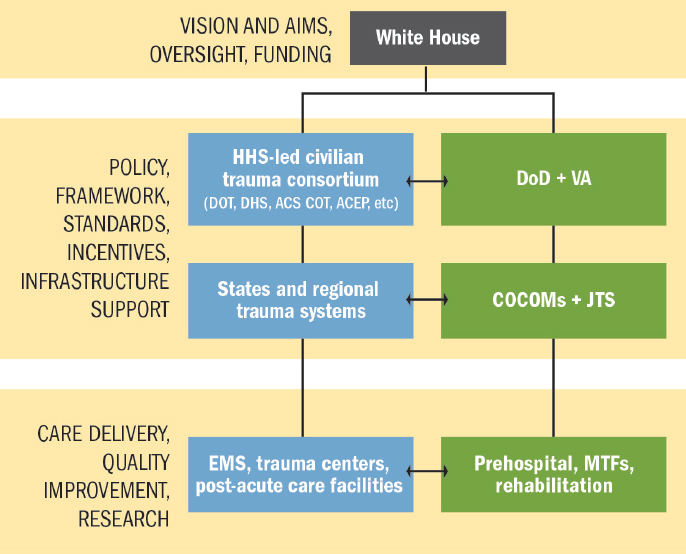

As envisioned by the committee, a national trauma care system encompasses both military and civilian trauma care systems—thus representing a system of systems. Centralized management of such a system by a single entity would be impracticable. Instead, an integrated framework defining roles and responsibilities at the various tiers of a national trauma care system (see Figure 8-3) is needed to implement this vision and to promote continuous learning at all levels, while holding leaders accountable for the successful functioning of the system. As described in Recommendations 1 and 2, the White House would direct the vision and aims and, through the Office of Management and Budget, ensure appropriate funding for the national system. Under the oversight of the White House, designated entities from both military and civilian sectors, working collaboratively with their governmental, private, and academic partners, would define the requirements, standards, policies, and procedures that the integrated system would execute to coordinate and advance trauma care (see Recommendations 3 and 4). To address the current fragmentation within the trauma care delivery system within and across prehospital, hospital-based, and post-acute care (which reflects the fragmentation of the health delivery system at large), the focus of these stakeholders would include the following areas:

NOTES: Blue boxes represent the civilian sector; green boxes represent the military sector. ACEP = American College of Emergency Physicians; ACS COT = American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma; CoCOM = combatant command; DHS = U.S. Department of Homeland Security; DoD = U.S. Department of Defense; DOT = U.S. Department of Transportation; EMS = emergency medical services; HHS = U.S Department of Health and Human Services; JTS = Joint Trauma System; MTF = military treatment facility; VA = U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

(1) capabilities, (2) education and training, (3) data collection, (4) performance improvement activities, (5) system-based and patient-centered research, (6) remediation of regulatory barriers, (7) resolution of financial challenges, (8) system design (e.g., infrastructure support), and (9) oversight. As depicted in Figure 8-3, the development of policies, standards, incentives, and support infrastructure would occur at multiple levels—both nationally and at the state/regional1 (civilian) or combatant command

__________________

1 Maryland’s Trauma Center Network—TraumaNet (see Box 2-1)—represents an example of a multidisciplinary organizational structure enabling a state-level collaborative approach to addressing all facets of trauma care delivery including systems of care (e.g., interhospital protocols and patient transfer policies), data collection, quality improvement, education, and research. Such a structure supports coordination and collaboration across up- and downstream components of the care continuum, as well as peer learning, from the state system level down to the individual trauma team.

(military) level. The recommendations that follow detail actions that can be taken to implement a joint framework that facilitates continuous learning and enables stakeholders to act in a coordinated manner to achieve the vision of an integrated national trauma care system. Potential operational-level strategies for better integrating military and civilian trauma care are included Appendix C.

A Framework for Transparency of Trauma Data

Learning and improvement are difficult, if not impossible, without a continual supply of data and narrative information, including but not limited to real-time assessments of performance against goals; process-related information, such as conformance to standards and guidelines; scientific studies and meta-analyses; and narratives from the actual field of practice. Learning systems are avid for such information, digest it rapidly, and maintain memory over time so that information accumulates and lessons are retained. Such an information environment has strong cultural characteristics as well, nurturing curiosity, disclosure, trust, and shared learning and always attending to minimizing fear. The emphasis is on data use for learning, not judgment. In a learning trauma care system, this bias toward information and data in the service of learning would take several forms, including robust and continuous registry-driven analyses, systems for communication and exchange of ideas, access to scientific insights, and total workforce engagement.

In both the military and civilian sectors, however, patient data are fragmented across independent data systems and registries, limiting the extent to which patient care and systems of care can be evaluated and improved. Linkages are incomplete or entirely missing among prehospital care, hospital-based acute care, rehabilitation/post-acute care, and medical examiner data. Such data, if collected at all, often reside in independent repositories. This design is suboptimal.

Conclusion: In the military and civilian sectors, the failure to collect, integrate, and share trauma data from the entire continuum of care limits the ability to analyze long-term patient outcomes and use that information to improve performance at the front lines of care. The collection and integration of data on the full spectrum of patient care and long-term outcomes using patient-centric, integrated registry systems need to be a priority in both sectors if the full potential of a learning trauma care system is to be realized, and if deaths from survivable injuries are to be reduced and functional outcomes maximized.

Given the fragmentation of current data systems, both military and civilian trauma care would benefit from a national architecture and frame-

work for the collection, integration, and sharing of trauma data spanning the full continuum of care across the military and civilian trauma systems to support the refinement of evidence-based trauma care practices. Such systems would enable well-validated measures of clinical processes and outcomes to be tracked and tied to performance. Interoperable, longitudinal registries could be used to track care processes and outcomes for many years, from the point of injury, including prehospital phases of care, to acute care; rehabilitation; and long-term physical, functional, and psychological outcomes. It would be important for this framework to provide experience in data collection, educating those responsible for capturing data across the trauma care continuum on the importance and value of doing so. A critical but often neglected source of data—particularly in civilian systems—is autopsy reports on trauma deaths, which could be used to determine the preventability of fatalities based on a common, accepted lexicon.

Recommendation 5: The Secretary of Health and Human Services and the Secretary of Defense, together with their governmental, private, and academic partners, should work jointly to ensure that military and civilian trauma systems collect and share common data spanning the entire continuum of care. Within that integrated data network, measures related to prevention, mortality, disability, mental health, patient experience, and other intermediate and final clinical and cost outcomes should be made readily accessible and useful to all relevant providers and agencies.

To implement this recommendation, the following specific actions should be taken:

- Congress and the White House should hold DoD and the VA accountable for enabling the linking of patient data stored in their respective systems, providing a full longitudinal view of trauma care delivery and related outcomes for each patient.

- The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology should work to improve the integration of prehospital and in-hospital trauma care data into electronic health records for all patient populations, including children.

- The American College of Surgeons, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, and the National Association of State EMS Officials should work jointly to enable patient-level linkages across the National EMS Information System project’s National EMS Database and the National Trauma Data Bank.

- Existing trauma registries should develop mechanisms for incorporating long-term outcomes (e.g., patient-centered functional outcomes, mortality data at 1 year, cost data).

- Efforts should be made to link existing rehabilitation data maintained by such systems as the Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation to trauma registry data.

- HHS, DoD, and their professional society partners should jointly engage the National Quality Forum in the development of measures of the overall quality of trauma care. These measures should include those that reflect process, structure, outcomes, access, and patient experience across the continuum of trauma care, from the point of injury, to emergency and in-patient care, to rehabilitation. These measures should be used in trauma quality improvement programs, including the American College of Surgeons Trauma Quality Improvement Program (TQIP).

Processes and Tools for Disseminating Trauma Knowledge

Given the intermittent nature of war, the nation requires a platform that can be used by the military to sustain the readiness of its medical force and advance best practices in trauma care during interwar periods. Such a platform would require formal conduits for the continuous and seamless exchange of knowledge and innovation between the military and civilian sectors. This system would offer the added benefit of facilitating more timely transfer of military lessons learned and innovations to the civilian sector to help address the nation’s tremendous burden of trauma.

Conduits for sharing knowledge can be synchronous or asynchronous.2 Clinical guidelines represent a form of explicit knowledge that can be diffused and implemented within and across sectors. The establishment of guidelines alone is not sufficient to reduce variation in care; guidelines must be maintained, distributed, and socialized to facilitate their widespread adoption. Furthermore, providers need near-real-time feedback on their performance (e.g., compliance with or deviation from the guidelines and associated patient outcomes) relative to that of their peers. Currently, however, information systems are not optimally designed or used to give providers real-time access to their (individual or team) performance data for improvement purposes.

Given the unique pragmatic considerations that inform guidelines for combat casualty care (e.g., disrupted care, care delivered over several health care facilities, time and distance), military and civilian guideline develop-

__________________

2 Synchronous learning occurs in real time through mechanisms that give the teacher and the learner simultaneous access to one another (e.g., one-to-one coaching sessions via telephone, classroom teaching), whereas asynchronous methods of learning allow learners to access information whenever they would like, not requiring the presence of an instructor (e.g., websites, guidelines).

ment processes need to remain separate efforts. By ensuring formal and robust processes for the exchange of information and ideas, however, DoD could support a national approach to the development of trauma care guidelines that would embrace the continuous learning process, enabling guidelines to be updated in real time in response to new evidence, facilitating continuous quality improvement, helping to inform policy, and saving lives.

Whereas explicit knowledge in the form of clinical guidelines can create familiarity with a concept, tacit knowledge comes from mastery through repetition. Relative to explicit knowledge, less attention typically is given to building conduits for the sharing of tacit knowledge—the kind of practical know-how that comes from experience at the front lines of care delivery and is much less easily codified. Yet timely access to this kind of knowledge is critical so that care providers can ask detailed, context-specific questions of those who have gained mastery in the process of doing their work instead of having to look the information up later. This access to “just-in-time” knowledge with a direct bearing on current challenges is extremely valuable, helping to reduce suffering and save lives. Telemedicine in particular has significantly advanced opportunities to disseminate best practices by ensuring real-time access to trauma experts.

Conclusion: The provision of tacit knowledge improves practice to reduce variation in patient care and outcomes. Yet participation in and support for resourcing of the processes and technologies that provide this knowledge remain limited in both the military and civilian sectors.

Conclusion: The military uses a flexible and agile approach to guideline development distinct from that used in the civilian sector. This pragmatic, focused empiricism approach enables rapid guideline development using best available data. However, the safety and effectiveness of care practices based on low-quality evidence need to be validated in due time through higher-quality studies carried out in conjunction with the civilian sector. Additionally, more formal processes are needed to encourage joint military–civilian discussion of guidelines so as to enhance bidirectional translation of knowledge and innovation between the two sectors.

Recommendation 6: To support the development, continuous refinement, and dissemination of best practices, the designated leaders of the recommended national trauma care system should establish processes for real-time access to patient-level data from across the continuum of care and just-in-time access to high-quality knowledge for trauma care teams and those who support them.

The following specific actions should be taken to implement this recommendation:

- DoD and HHS should prioritize the development and support of programs that provide health service support and trauma care teams with ready access to practical, expert knowledge (i.e., tacit knowledge) on best trauma care practices, benchmarking effective programs from within and outside of the medical field and applying multiple educational approaches and technologies (e.g., telemedicine).

- Military and civilian trauma management information systems should be designed, first and foremost, for the purpose of improving the real-time front-line delivery of care. These systems should follow the principles of bottom-up design, built around key clinical processes and supporting actors at all levels through clinical transparency, performance tracking, and systematic improvement within a learning trauma care system. Therefore, the greater trauma community, with representation from all clinical and allied disciplines, as well as electronic medical record and trauma registry vendors, should, through a consensus process, lead the development of a bottom-up data system design around focused processes for trauma care.

- HHS and DoD should work jointly to ensure the development, review, curation, maintenance, and validation of evidence-based guidelines for prehospital, hospital, and rehabilitation trauma care through existing processes and professional organizations.

- Military and civilian trauma system leaders should employ a multipronged approach to ensure the adoption of guidelines and best practices by trauma care providers. This approach should encompass clinical decision support tools, performance improvement programs, mandatory predeployment training, and continuing education. Information from guidelines should be included in national certification testing at all levels (e.g., administrators, physicians, nurses, physician assistants, technicians, emergency medical services).

One example of a program that could be institutionalized and expanded to facilitate the transfer of tacit knowledge as suggested in Recommendation 6 is the Senior Visiting Surgeon Program. The expansion of this best practice beyond surgeons to include other critical members of the trauma team (e.g., emergency medicine physicians, nurses, medics, technicians) presents opportunities for developing stronger links between military and civilian sectors across all disciplines, facilitating deeper integration in the context of a national trauma care system.

A Collaborative Military–Civilian Research Infrastructure in a Supportive Regulatory Environment

Unlike other fields (e.g., infectious disease) challenged by emerging threats, trauma is, in many ways, highly predictable. For example, it has been recognized for decades that hemorrhage is the leading cause of preventable death on the battlefield (Bellamy, 1984; Lindsey, 1957). Great progress has been made over the last 15 years in the development of innovative devices, therapeutics, and knowledge that can improve the delivery of trauma care (DHB, 2015). However, many remaining gaps need to be addressed before the next major conflict so that lives will not continue to be lost as a result of the same preventable and foreseeable causes. As stated by Dr. Luciana Borio, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) acting chief scientist,

The time to contemplate the research portfolio for hemorrhage for the DoD is not right before deployment. It’s going to be the number one or two or three problem for the DoD in the warfighter, and the warfighter being the most precious resource for DoD, I think we need to really put a lot of energy into making sure we have a robust national portfolio to deal with the problem with hemorrhage. (Borio, 2015)

DoD and its civilian partners also need to be preparing for new challenges that different kinds of warfare may bring in the future. Extremity trauma and head injury due to blast injuries, for example, were encountered far more frequently during Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom than in past wars, and have generated an increased need for research on rehabilitative care.

The sense of urgency to develop solutions to address preventable death and disability after injury needs to be sustained through the interwar period. “Even in austere times, the military remains uniquely obligated to maintain its commitment to trauma research as a matter of national security” (Rasmussen and Baer, 2014, p. 221). Resolving remaining capability gaps will require a collaborative research infrastructure and research investment commensurate with the importance of the problem and the potential for improvement in trauma patient outcomes. Models for collaborative research, such as the Major Extremity Trauma Research Consortium (see Box 4-5), have the potential to yield lifesaving and life-changing advances for severely injured patients in both military and civilian settings but require sustained support. Current infrastructure and funding levels clearly fall far short of the mark, perpetuating fundamental knowledge gaps that impede the delivery of optimal trauma care.

Conclusion: Investment in trauma research is not commensurate with the burden of traumatic injury. To address critical gaps in knowledge of

optimal trauma care practices and delivery systems, the United States needs a coordinated trauma research program with defined objectives, a focus on high-priority needs, and adequate resourcing from both the military and civilian sectors.

In 2012, President Obama issued an executive order directing federal agencies to create a National Research Action Plan (NRAP) on posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), other mental health conditions, and traumatic brain injury (TBI) (White House, 2012). This presidential directive, although an unfunded mandate, has been successful in drawing attention to the issue of TBI; generating additional research investment; and requiring government agencies to coordinate their efforts, both in the development of the NRAP (which was released in August 2013) and in future research efforts. The success of the NRAP effort demonstrates how executive action from the White House can draw attention to overlooked areas of research in the absence of a funded congressional mandate and could serve as a model for a broader all-of-trauma initiative aimed at inducing federal agencies to better coordinate their research efforts.

Recommendation 7: To strengthen trauma research and ensure that the resources available for this research are commensurate with the importance of injury and the potential for improvement in patient outcomes, the White House should issue an executive order mandating the establishment of a National Trauma Research Action Plan requiring a resourced, coordinated, joint approach to trauma care research across the U.S. Department of Defense, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (National Institutes of Health, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute), the U.S. Department of Transportation, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, and others (academic institutions, professional societies, foundations).

This National Trauma Research Action Plan should build upon experience with the successful model of the NRAP and should

- direct the performance of a gap analysis in the military and civilian sectors that builds on previous analyses, looking at both treatment (clinical outcome studies) and systems research to identify gaps across the full continuum of care (prehospital and hospital-based care and rehabilitation) and considering needs specific to mass casualty incidents (e.g., natural disasters, terrorist attacks) and special patient populations (e.g., pediatric and geriatric patient populations);

- develop the appropriate requirements-driven and patient-centered research strategy and priorities for addressing the gaps with input from armed forces service members and civilian trauma patients;

- specify an integrated military–civilian strategy with short-, intermediate-, and long-term steps for ensuring that appropriate military and civilian resources are directed toward efforts to fill the identified gaps (particularly during interwar periods), designating federal and industry stakeholder responsibilities and milestones for implementing this strategy; and

- promote military–civilian research partnerships to ensure that knowledge is transferred to and from the military and that lessons learned from combat can be refined during interwar periods.

The execution of a National Trauma Research Action Plan would certainly require a significant infusion of trauma research funding. This funding should be based on a determination of need stemming from the gap analysis recommended above and a review of current investments.

The need for a robust national trauma research enterprise also creates demands on the regulatory environment, which needs to consciously foster learning and knowledge exchange, or at least not be inimical to them, even while protecting the interests of human subjects and addressing privacy concerns. A separate National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine committee—the Committee on Federal Research Regulations and Reporting Requirements—was charged with broadly reviewing federal regulations and reporting requirements and developing a new framework for federal regulation of research institutions. That committee has released a two-part report, which recommends actions to improve the efficiency of federal regulations (NASEM, 2016). While not specifically charged with such a comprehensive evaluation of federal research regulations, many of the present committee’s findings were congruent with theirs. As a result of the existing federal regulatory landscape—not just the regulations themselves but also their interpretations—military and civilian trauma systems share barriers to the effective functioning of a learning system. As a result, critical research and quality improvement activities are not being conducted.

Conclusion: A learning trauma care system cannot function optimally in the current federal regulatory landscape. Federal regulations or their interpretations often present unnecessary barriers to quality improvement and research activities. Lack of understanding of relevant provisions of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act has resulted in missed opportunities to share data across the continuum of care in both the military and civilian sectors.

Recommendation 8: To accelerate progress toward the aim of zero preventable deaths after injury and minimizing disability, regulatory agencies should revise research regulations and reduce misinterpretation of the regulations through policy statements (i.e., guidance documents).

In the process of implementing this recommendation, the following issues are points to consider:

- Prior national committees and legislative efforts have recommended that Congress, in instances of minimal-risk research where requiring informed consent would make the research impracticable, amend the FDA’s authority so as to allow the FDA to develop criteria for waiver or modification of the requirement of informed consent for minimal-risk research. The present committee supports these recommendations, which would address current impediments to the conduct of certain types of minimal-risk research in the trauma setting (e.g., diagnostic device results that would not be used to affect patient care).

- For nonexempt human subjects research that falls under either HHS or FDA human subjects protections as applicable, DoD should consider eliminating the need to also apply 10 U.S.C. § 980, “Limitation on Use of Humans as Experimental Subjects” to the research.

- HHS’s Office for Civil Rights should consider providing guidance on the scope and applicability of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) with respect to trauma care and trauma research such that barriers to the use and disclosure (sharing) of protected health information across the spectrum of care (from the prehospital or field setting, to trauma centers and hospitals, to rehabilitation centers and long-term care facilities) will be minimized.

- The FDA, in consultation with DoD, should consider establishing an internal Military Use Panel, including clinicians with deployment experience and patient representative(s) (i.e., one or more injured soldiers), that can serve as an interagency communication and collaboration mechanism to facilitate more timely fielding of urgently needed medical therapeutic and diagnostic products for trauma care.

- In trauma settings in which there are unproven or inadequate therapeutic alternatives for life-threatening injuries, the FDA should explore the appropriate scientific and ethical balance between pre-market and postmarket data collection such that potentially lifesaving products are made available more quickly (after sufficient

-

testing). At the same time, the FDA should consider developing innovative methods for addressing data gaps in the postmarket setting that adhere to regulatory and statutory constraints.

- Consistent with its approach to applications for rare diseases, the FDA should consider exercising flexibility in evidentiary standards for effectiveness within the constraints of applicable law when a large body of clinical evidence (albeit uncontrolled) supports a new indication for an FDA-approved product for the diagnosis or treatment of traumatic injury, and pragmatic, scientific, or ethical issues constrain the conduct of a randomized controlled trial (e.g., on the battlefield or in the prehospital setting).

- A learning trauma care system involves continuous learning through pragmatic methods (e.g., focused empiricism) and activities that have elements of both quality improvement and research. HHS, when considering revisions to the Common Rule, should consider whether the distinction it makes between quality improvement and research permits active use of these pragmatic methods within a continuous learning process. Whatever distinction is ultimately made by HHS, the committee believes that it needs to support a learning health system. Additionally, HHS, working with DoD, should consider providing detailed guidance for stakeholders on the distinctions between quality improvement and research, including discussion of appropriate governance and oversight specific to trauma care (e.g., the continuum of combat casualty care, and prehospital and mass casualty settings).

The FDA is an invaluable asset to DoD in ensuring that research aimed at developing knowledge that can improve care for service members is conducted in the most informative and valuable manner while minimizing risks to research subjects. To this end, the FDA’s Emergency Preparedness and Medical Countermeasures Program within the Center for Devices and Radiological Health has made important efforts to promote greater cooperation and efficiency in its interactions with the military through early-stage discussions on medical device development projects (Kumar and Schwartz, 2015). This new paradigm featuring a more collaborative approach to the FDA’s regulatory process can serve as a model for the broader partnership envisioned by the committee for the proposed Military Use Panel. This panel would have multiple purposes:

- Promotion of discussions early in the development of medical products that would include the FDA regulatory review division and other relevant FDA offices. The goal of these discussions would be identifying acceptable paths forward (e.g., scientific, regulatory,

-

ethical, contextual) for clinical research on medical therapeutic products for battlefield trauma care. Given the urgency of the need, this interagency and cross-agency collaboration should be designed to be as efficient and seamless as possible such that lifesaving products will be accessible as quickly as possible.

- Translation of scientific, regulatory, ethical, and policy lessons learned from trauma research in the military context to the civilian context such that the design of trauma-related research and product development will benefit from deliberations and considerations in the military sector.

- Provision of the specific military context and considerations to the FDA to inform discussions of the expansion of FDA-labeled indications to include approval for a military indication (not to be conflated with military use only). Matters to be deliberated would include but not be limited to evidentiary standards compliant with FDA statutory limitations, the feasibility and ethics of conducting controlled research within the combat setting, pragmatic clinical trials versus traditional clinical trials, and alternative research designs or empiric data gathering mechanisms acceptable to the FDA when controlled clinical trials are impracticable or unethical.

- In combination with the FDA regulatory review division and other relevant FDA offices, evaluation of products that have been approved for use by NATO allies and have applications for the U.S. military to determine whether the extant associated empiric evidence would support FDA approval for the use under consideration (and if not, what additional evidence would be needed for approval and how clinical trials could be designed and conducted).

It should be emphasized that the committee does not intend that this panel would be used to work toward military-use-only indications for therapeutic and diagnostic devices. The committee sees a number of problems with military-specific approvals. For example, limiting the use of a drug, device, or biologic to the military prevents the civilian sector from benefiting from that intervention. In addition, these indications create a restricted market for manufacturers and limit military use to the deployed setting, preventing the military from training in and using the products in the United States. Rather, the intent in recommending the establishment of such a panel is to create an ongoing forum for discussion that would cut across the various centers and offices of the FDA so that discussions between the military and the FDA would not occur solely on a product-by-product basis.

Systems and Incentives for Improving Transparency and Trauma Care Quality

Elements that promote the adoption of innovations and best practices include a leadership-instilled culture of learning and improvement, incentives, and mechanisms for identifying potentially beneficial practices from other organizations and sectors (IOM, 2013). Each is critical to a national system for trauma care that would ensure the diffusion of best practices within and across the military and civilian sectors.

Reporting on performance data and practice variation can drive the adoption of evidence-based trauma care practices by providing a mechanism for comparison across centers and systems and identifying practices and design elements associated with superior performance. Although the American College of Surgeons Trauma Quality Improvement Program (TQIP) enables comparison across trauma centers, no mechanism currently exists to enable comparison across systems for prehospital care or regional trauma systems as a whole.

Conclusion: The absence of a comprehensive, standardized process by which the military and civilian sectors engage in system-level trauma care quality improvement impedes learning, continuous improvement, and the bidirectional translation of best practices and lessons learned.

Recommendation 9: All military and civilian trauma systems should participate in a structured trauma quality improvement process.

The following steps should be taken to enable learning and improvement in trauma care within and across systems:

- The Secretary of HHS, the Secretary of Defense, and the Secretary of the VA, along with their private-sector and professional society partners, should apply appropriate incentives to ensure that all military and civilian trauma centers and VA hospitals participate in a risk-adjusted, evidence-based quality improvement program (e.g., ACS TQIP, Vizient).

- To address the full continuum of trauma care, the American College of Surgeons should expand TQIP to encompass measures from point-of-injury/prehospital care through long-term outcomes, for its adult as well as pediatric programs.

- The Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation should pilot, fund, and evaluate regional, system-level models of trauma care delivery from point of injury through rehabilitation.

Widespread participation in a structured trauma quality improvement process, spanning the continuum of care,3 would support horizontal learning (i.e., among peers) and vertical learning (i.e., from upstream and downstream collaborators). Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation pilots would help identify and diffuse best practices in trauma system design and care delivery that are contributing to superior outcomes at high-performing trauma systems. One group has estimated that the lives of nearly 100,000 Americans could be saved over a 5-year period if all trauma centers achieved outcomes similar to those at the highest-performing centers (Hashmi et al., 2016). The potential to save lives may be even greater if similar improvements could be made at the system level, inclusive of prehospital and post-acute care.

Learning from the military experience, the greatest opportunity to save lives is in the prehospital setting and the integration of prehospital care into the broader trauma care system is needed to ensure the delivery of optimal trauma care across the health care continuum, best understand the impact of trauma care, and recognize and address gaps and requirements to prevent deaths after injury. Because emergency medical services (EMS) is not currently a provider type designated under the Social Security Act, HHS does not link the emergent medical care delivered out of hospital to value-based payment or other current health care reform efforts. As a result, EMS continues to be a patchwork of systems across the nation with differing standards of care, few universal protocols, and perverse payment standards, yielding inconstant quality of care and variable patient outcomes. Such a system is not optimally designed to serve as a training platform for the military during interwar periods. Recognizing that a centralized model of prehospital care delivery is impracticable, national leadership is needed to define the requirements, standards, incentives, policies, and procedures that will ensure the adoption of best practices and the integration of prehospital care as a seamless component of the trauma care delivery system (see Figure 8-3). Without universal integration and structured governance, prehospital care will not become a truly functional part of the effort to prevent deaths and limit disability.

Conclusion: A national system-based and patient-centered approach to prehospital trauma care is needed in the civilian sector to incentivize improved care delivery, the rapid broad translation of military best practices, reduced provider and system variability, uniform data collection and performance improvement, and integration with hospital

__________________

3 As the VA is a major provider of rehabilitative care for veteran service members who sustained injuries during combat operations, it is important for VA hospitals to participate in trauma system quality improvement processes.

trauma systems so that comprehensive trauma care can be evaluated for quality performance. However, designation of emergency medical services as a supplier of transportation under the Social Security Act impedes the seamless integration of prehospital care into the trauma care continuum and its alignment with health care reform efforts.

Recommendation 10: Congress, in consultation with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, should identify, evaluate, and implement mechanisms that ensure the inclusion of prehospital care (e.g., emergency medical services) as a seamless component of health care delivery rather than merely a transport mechanism.

Possible mechanisms that might be considered in this process include, but are not limited to:

- Amendment of the Social Security Act such that emergency medical services is identified as a provider type, enabling the establishment of conditions of participation and health and safety standards.

- Modification of CMS’s ambulance fee schedule to better link the quality of prehospital care to reimbursement and health care delivery reform efforts.

- Establishing responsibility, authority, and resources within HHS to ensure that prehospital care is an integral component of health care delivery, not merely a provider of patient transport. The existing Emergency Care Coordination Center could be leveraged as a locus of responsibility and authority (see Recommendation 4) but would need to be appropriately resourced and better positioned within an operational division of HHS to ensure alignment of trauma and emergency care with health delivery improvement and reform efforts.

- Supporting and appropriately resourcing an EMS needs assessment to determine the necessary EMS workforce size, location, competencies, training, and equipping needed for optimal prehospital medical care.

The changes necessary to integrate prehospital care as a seamless component of health care, including those mechanisms suggested above, would have vast implications that warrant thorough reflection. The application of existing certification standards to EMS agencies, for example, would need to be considered when amending the Social Security Act, a complex piece of legislation. Recognizing the complexities of the proposed actions, the committee strongly believes the inclusion of prehospital care within health care reform efforts through implementation of this recommendation is critical

to the development of a patient-centered, comprehensive approach to the delivery of trauma care across the nation. Under the proposed consideration for change in legislation, minimum health and safety standards would be established, including the need for medical oversight, a data collection mechanism linked to hospital based care, a performance improvement system, and a patient safety program. Additionally, modifying the Social Security Act to define EMS as a provider type could prompt CMS to develop a trauma or emergency care-based shared savings model with relevant metrics that could be used to measure the value of prehospital care delivered, including patient outcomes and the appropriateness of the facilities receiving patients.

Although a national EMS assessment was released in 2011 that described the present state of EMS (FICEMS, 2011), what is needed now is a comprehensive assessment that articulates the needs of a population for EMS and how the nation should better position and deliver care in the prehospital environment.

Platforms to Create and Sustain an Expert Trauma Care Workforce

The readiness mission of the Military Health System requires that a network of military medical teams—comprising expert clinical providers (physicians, nurses, allied health professionals) and support professionals (administrators, managers, information technology personnel, data managers)—be readily available to deploy on short notice in support of military operations. The nation’s service members deserve the same high standard of care and specialty care available at any Level I trauma center in the United States. To this end, military trauma teams need to train to an expert level. Yet most military teams sent to care for injured service members during Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom would not have been allowed to care for trauma patients at a civilian Level I trauma center. The development of an expert trauma care workforce requires a significant investment of both time and resources, necessitating in some cases more than a decade of education and specialty medical training. This investment also must extend to include the education and training of senior line and medical leaders on trauma system concepts as well as the importance of sustaining and continuously improving the military trauma system.

When the next military conflict inevitably transpires, there will be little time to reconstruct an optimal combat casualty care capability from a diminished state of readiness. DoD cannot wait until the next war to begin the process of generating a ready medical force to meet its wartime needs. However, DoD alone cannot maintain the readiness of an expert military trauma care workforce that can deliver the volume and quality of trauma care needed to support service members on the battlefield. As discussed in Chapter 5, the main problem is that the Military Health System simply does

not see the clinical volume of trauma cases during interwar periods necessary for trauma teams to acquire and maintain expertise in trauma care. No credible plan appears to be in place to address this problem, which virtually ensures that wounded combatants in a future war will, at least for a time, have worse outcomes than would have been achieved with full readiness. If the lessons from the past 15 years are not sustained and history repeats itself, the next war will see wounded military personnel lose lives and limbs that should have been saved.

Conclusion: To eliminate preventable mortality and morbidity at the start of and throughout future conflicts, comprehensive trauma training, education, and sustainment programs throughout DoD are needed for battlefield-critical physicians, nurses, medics, administrators, and other allied health professionals who comprise military trauma teams. This effort will ensure that a ready military medical force with expert combat casualty care skills is sustained throughout peacetime. A single military leader (general officer) needs to be accountable for generating and sustaining this education and training platform across the Military Health System to deliver trauma experts to the battlefield. In addition, line and medical leaders need to be held accountable for the results delivered by their trauma teams on the battlefield.

The best clinical outcomes come from high-functioning trauma teams with substantial administrative commitment, experienced in all elements of trauma care, that care for trauma patients on a daily basis, and in which all team members (physicians, nurses, medics, technicians, and administrators) know what their responsibilities are. Much as military line leadership trains constantly for combat, military trauma teams need to care for trauma patients repeatedly, on a daily basis. Enabling all providers, administrators, and leaders within the Military Health System to have experience with trauma care on a daily basis would ensure the highest-quality care for combat casualties.

An expert military trauma workforce needs to be developed and sustained to achieve trauma care capabilities defined by DoD—specifically, the Joint Capabilities Integration and Development System—as necessary to the success of its wartime mission. Meeting this need will require trauma-specific career paths with defined standards for competency and increased integration of the Military Health System and civilian trauma systems.

Recommendation 11: To ensure readiness and to save lives through the delivery of optimal combat casualty care, the Secretary of Defense should direct the development of career paths for trauma care (e.g., foster leadership development, create joint clinical and senior leader

ship positions, remove any relevant career barriers, and attract and retain a cadre of military trauma experts with financial incentives for trauma-relevant specialties). Furthermore, the Secretary of Defense should direct the Military Health System to pursue the development of integrated, permanent joint civilian and military trauma system training platforms to create and sustain an expert trauma workforce.

Specifically, within 1 year, the Secretary of Defense should direct the following actions:

- Ensure the verification of a subset of military treatment facilities (MTFs) by the American College of Surgeons as Level I, II, or III trauma centers where permanently assigned military medical personnel deliver trauma care and accumulate relevant administrative experience every day, achieving expert-level performance. The results of a needs assessment should inform the selection of these military treatment facilities, and these new centers should participate fully in the existing civilian trauma system and in the American College of Surgeons’ TQIP and National Trauma Data Bank.