1 Introduction

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

—George Santayana (1905)

On January 29, 2016, Bob Woodruff celebrated his 10th Alive Day—marking the day he should have died, but didn’t. Ten years earlier, the reporter and recently appointed co-anchor for ABC’s World News Tonight was embedded with the Army’s 4th Infantry Division in Taji, Iraq, covering the handover of the U.S. military’s security mission to the native Iraqi forces. On January 29, 2006, Bob and his cameraman were filming from the top of an Iraqi armored vehicle when the convoy came under attack. The detonation of a roadside improvised explosive device (IED) sent shrapnel ripping through the air. More than 100 rocks were blasted into the left side of Bob’s head and upper body. A rock the size of a half dollar entered the left side of his neck, traveling across to lodge in the right side, just adjacent to his carotid artery. Other rocks shot through the armhole of his flak jacket, producing a fist-sized hole in his back and shattering his scapula. Incredibly, the rocks stopped a millimeter short of his chest wall. The force of the IED blast shattered Bob’s skull over the left temporal lobe—the region of the brain responsible for speech and language—sending bone shards into the outer surface of his brain and slightly displacing his left eye from the socket.

Bob might have died within minutes if not for the quick actions of his colleague and producer, who was instructed by the Iraqi interpreter in the vehicle to put pressure on the gaping neck wound, which had been pumping out blood. Amid active gunfire, an Army helicopter landed to evacuate the

injured. Bob was flown to a military hospital in Baghdad, where he was assessed and stabilized before being flown to a field hospital in Balad, Iraq, capable of dealing with his severe injuries. An Army neurosurgeon operated on Bob’s head injury as insurgents shelled the hospital with mortars. The military surgical team removed a piece of his skull 16 cm across to relieve the rapid swelling in his brain and prevent further injury from rising pressure within the skull. He would live without that piece of his skull for almost 4 months.

The next day, Bob was flown to Landstuhl Regional Medical Center in Germany, where he underwent further surgeries to remove rocks and other debris, remaining there for approximately 60 hours before being transferred to Bethesda Naval Hospital in Washington, DC. For both flights, Bob was transported on a U.S. Air Force plane specially outfitted to transport patients with all of their medical equipment and a dedicated medical team. The unique capability of the Critical Care Air Transport Teams has substantially shortened the time required to move combat casualties out of the Middle East theater of operations to trauma centers in both Germany and the United States. During the Vietnam War, the full evacuation sequence could have taken more than 45 days.

Bob was unconscious for 36 days. During that time, there was no way to know the extent of the impact of his injuries on his physical abilities—speech and hearing—or cognitive function. Would he be prone to sudden angry outbursts or inappropriate behavior, depression, or posttraumatic stress disorder? All are telltale signs of traumatic brain injury—a haunting legacy of the wars in the Middle East.

On March 6, 2006, Bob woke up. Despite his uncertain prognosis, the degree and speed of his recovery were remarkable. In those early days, listening, speaking, and even thinking were challenging, and it seemed to Bob as though his brain had been shifted into a lower gear, a sensation likened to trying to swim through Jello. He had difficulty retrieving certain words, a condition known as aphasia. For Bob and his family, the recovery process would feel painstaking and unending, but with their support, the fog lifted little by little each day. In October 2006, just 9 months after his injury, he returned to work at ABC News.

Bob received the same standard of quality trauma care afforded to every military service member. He was treated by world-class surgeons, nurses, and other military medical professionals whose knowledge of best treatment practices for traumatic brain injury had been greatly advanced through years of experience during the war—experience and knowledge that today, 10 years later, has yet to be fully and systematically passed on to their civilian counterparts. As doctors would later confide to his wife,

Lee, had this kind of traumatic brain injury occurred in the United States instead of that Iraqi desert, Bob likely would not have survived.1

BACKGROUND AND RATIONALE FOR THIS STUDY

More than any other events in history, the exigencies of war have advanced the care of the injured. American surgeons returning from the battlefields of every national conflict since the Civil War have brought home to civilian care the advances of military medicine (Pruitt, 2008; Trunkey, 2000). One fundamental lesson learned over the years is that surviving a major injury depends on optimal prehospital care and the minimizing of time to definitive care, made possible today by highly organized trauma systems that support the timely identification and triage of patients to a level of care commensurate with the extent and severity of their injuries. Although an organized structure for evacuation of battlefield casualties to a system of hospitals with waiting surgeons was first developed by the U.S. military during the Civil War (Manring et al., 2009), advances made during the conflicts in Korea and Vietnam have had the most notable role in shaping this modern systems approach to trauma care (see Box 1-1).

Unfortunately, however, the military has faced throughout history the recurring problem that wartime advances in trauma care are neither sustained during the interwar period nor fully translated to the civilian sector. Haphazard collection of medical histories and inadequate archiving of lessons learned have contributed to the loss of knowledge as military physicians, nurses, and other care providers have returned to their civilian lives (Churchill, 1952, 1972). The price of the resultant decline in readiness to deliver battlefield care is paid in the lives of the men and women first to deploy at the start of the next conflict, as the military health system is forced to relearn those lessons lost (DeBakey, 1996; Gross, 2015) (see Box 1-2). Because the military has historically relied on the voluntary and obligatory recruitment of medical professionals from the civilian sector during wartime, further integration of the military and civilian trauma communities is critically important to ensure that military readiness is maintained between conflicts and that trauma care improves in both settings (Eastman, 2010; Schwab, 2015).

The 1966 National Academy of Sciences report Accidental Death and Disability: The Neglected Disease of Modern Society (NRC, 1966) first brought to light the little-known fact that injury is a leading cause of death

__________________

1 This account of Bob Woodruff’s injury in Iraq and the trauma care he subsequently received through the military’s trauma care system was drawn from that published in the Woodruffs’ book, In an Instant: A Family’s Journey of Love and Healing. The use of his story in this report was approved by Mr. Woodruff.

and disability among Americans (Rhee et al., 2014) and issued a call to action to translate the lessons learned from war to the civilian sector. The report identified advancing care of the injured as a moral imperative, reflecting on how poorly the average citizen might fare if struck by a motor vehicle in a large U.S. city compared with a soldier wounded in a rice paddy in Southeast Asia. The report called for efforts to blanket the United States with overlapping, regional trauma systems to ensure that wherever an injury might occur, a coordinated system of care would be in place to provide the best care possible.

In the 50 years since that report was published, both the military and civilian sectors have made significant progress toward achieving this goal. In both settings, this progress has been due in large measure to the commitment of key champions, the development of uniform (albeit disconnected) data collection systems, and the use of these data for continuous quality improvement. In the civilian sector, an early federal government investment in the development of infrastructure at the state and regional levels,2 combined with political will in some pioneering states to enact trauma system legislation, also played an important role (Bailey et al., 2012a,b; Eastman et al., 2013). Now statewide and regional trauma systems and trauma centers are ubiquitous across the country, albeit of varying capabilities and coverage. Encouraging is the fact that more than 80 percent of Americans now have access to a Level I or Level II trauma center within 1 hour by land or by air (Branas et al., 2005).

Building on this progress in the civilian sector, the military invested in the development of the U.S. Department of Defense’s (DoD’s) formal trauma system, the Joint Trauma System (JTS), and its associated trauma registry (discussed in more detail in Chapter 4) to meet combat casualty care needs during the wars in Iraq (Operation Iraqi Freedom) and Afghanistan (Operation Enduring Freedom). Since its inception, the JTS has served as the military’s coordinating entity for trauma care. The DoD Trauma Registry (DoDTR) is the largest repository of combat injury and trauma care data. The collection of DoDTR data and its integration with the military’s requirements-driven research program represents a novel approach to trauma care in the military, as does the prompt and practical translation of evidence stemming from those registry data and research into JTS performance improvement processes, such as the development of clinical practice guidelines and the use of telemedicine conferencing (Blackbourne et al., 2012). Through its efforts to enhance outcomes using evidence-based performance improvement processes, the military has worked toward establishing what the Institute of Medicine refers to as a “continuously learning

__________________

2 The committee uses the term “regional” here to indicate trauma systems organized at the substate level and those that cross neighboring state boundaries.

health system” (IOM, 2013), in which its trauma care experience is captured, integrated with its research program, and systematically translated into more reliable care (described in more detail in Chapter 3).

Between 2005 and 2013, the case fatality rate (CFR)3 for U.S. service members injured in Afghanistan decreased by nearly 50 percent, despite an increase in the severity of injury among U.S. troops during that same period (Bailey et al., 2013; Rasmussen et al., 2013). This improvement in combat survival has been attributed in part to the development of the JTS and the military’s dedicated investment in trauma research and care (Bailey et al., 2013; Elster et al., 2013a; Rasmussen et al., 2013).

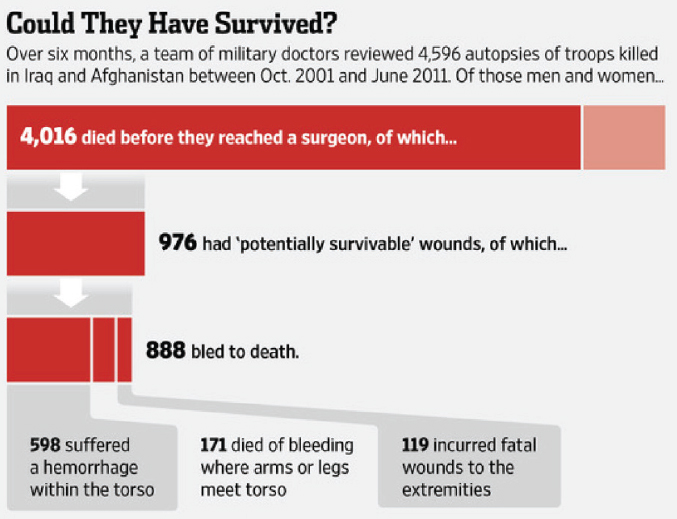

Despite these efforts, however, nearly 1,000 soldiers, sailors, airmen, and marines died of potentially survivable injuries4 during Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom (Eastridge et al., 2012). A review of U.S. service member deaths occurring in theater5 using data from the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System showed that approximately 25 percent of prehospital deaths (2001-2011) and 50 percent of in-hospital deaths (2001-2009) were potentially medically preventable. The vast majority of these fatalities (80.0 and 90.9 percent for in-hospital and prehospital deaths, respectively) were associated with hemorrhage (Eastridge et al., 2011, 2012). Acknowledging this information is painful to military leadership and, especially, to the families of those who died. However, those leaders and families surely would agree that to honor and learn from the sacrifice of these service members, it is necessary to talk openly about this issue and work as hard as possible to improve the military trauma care system so that there are zero preventable deaths after injury (defined in Box 1-3) in the next war.

The extent to which preventable deaths permeate civilian trauma systems is equally alarming. A recent meta-analysis of hospital trauma deaths found that approximately 20 percent were survivable (Kwon et al., 2014).6 Thus, despite progress in both the civilian and military sectors, significant gaps in trauma care remain. Across both sectors, the quality of trauma care

__________________

3 Case fatality rate (CFR) is the percentage of fatalities among all wounded individuals (Holcomb et al., 2006).

4 Survivability determinations were based on medical information only and did not take into account resource restrictions or operational conditions that may have prevented timely access to medical care (Eastridge et al., 2012).

5 The term “theater” refers to the theater of war, which is the area of air, land, and water that is, or may become, directly involved in the conduct of the war (DoD, 2016).

6 The meta-analysis by Kwon and colleagues (2014) yielded the most robust estimate of preventable death after injury identified by the committee. It should be noted, however, that the studies included in that analysis were largely from outside the United States and focused on in-hospital deaths. At this time, data on prehospital trauma deaths in the civilian sector are lacking. Therefore, the overall incidence of preventable death after injury is likely higher than that found by Kwon and colleagues (2014).

and outcomes for injured patients vary greatly; briefly put—where one is injured may determine whether one survives. From these findings, it is clear that swift and decisive action is warranted to address the state of trauma care and the significant burden of injury in military and civilian systems.

With the drawdown of U.S. troops from Afghanistan and Iraq, the nation once again has an opportunity to benefit from the lessons learned about trauma care from the past 15 years of war and ensure that they are not forgotten. Failure to do so will have deadly consequences. Unfortunately, however, as the wars end and service members continue to leave the military, the experience, knowledge, and advances in trauma care gained over the past decade are being lost. This loss has implications for the quality of trauma care both in the military and in the civilian sector, where the adoption of military advances can improve the delivery of everyday trauma care and the response to multiple-casualty incidents. Recent events in Sandy Hook, Boston, Paris, and San Bernardino highlight the unfortunate reality that active shooter and mass casualty incidents have become increasingly common in everyday American life and lend urgency to the translation of wartime lessons in trauma care to the civilian sector. During an interwar period, however, degradation of the military’s integrated education and training, research, and trauma care programs can impede cross-sector pollination.

The Societal Burden of Traumatic Injury

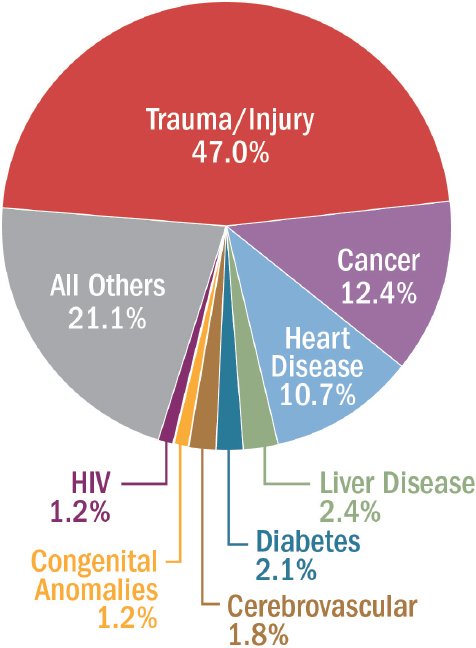

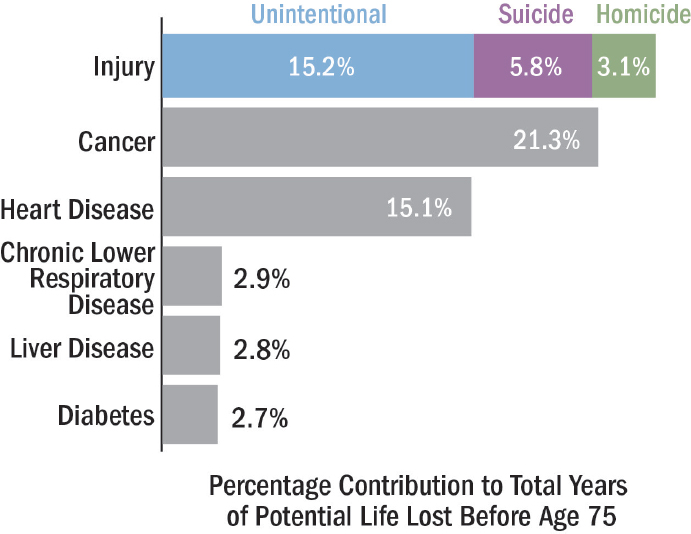

The societal burden of traumatic injury is staggering, resulting from wounds sustained not just on the battlefield but also in everyday civilian life. Trauma, comprising both unintentional and intentional injuries,7 is the third leading cause of death overall in the United States (NCIPC, 2015c). Unlike other leading causes of death, moreover, which typically affect individuals later in life, trauma disproportionately affects the young, killing those who might otherwise have lived long and productive lives8 (NRC, 1966). As noted earlier, injury remains the leading cause of death among children and adults under the age of 46, accounting for nearly half of all deaths in this age group (Rhee et al., 2014) (see Figure 1-1). Together, unintentional and intentional injuries account for more years of potential life lost before age 75 than any other cause, including cancer or heart disease (NCIPC, 2015d) (see Figure 1-2). In 2014, there were 147,790 civilian deaths from trauma9 (NCIPC, 2015b), more than 10,000 of which were among children10 (NCIPC, 2015a). Assuming that as many as 20 percent of civilian trauma deaths are the result of survivable injuries (Kwon et al., 2014), had they received optimal trauma care, the lives of nearly 30,000 Americans might have been saved in 2014 alone.

Globally, the trends are even more disconcerting. In 2010, trauma accounted for 5.1 million deaths, almost 1 in 10 deaths, worldwide. Trauma deaths disproportionately affect low- and middle-income countries. Whereas trauma caused 6 percent of deaths in high-income countries in 2010, it accounted for 11 percent of deaths in low-income countries in Southeast Asia and 12 percent of deaths in low-income countries in the Americas (Norton and Kobusingye, 2013). In developing nations, children are especially vulnerable to death from injury (Brown, 2015). Across the world, more than 2,000 children die daily from unintentional injury alone (Peden et al., 2008). As in the United States, the burden of injury is expected to rise globally over the coming decades (Rhee et al., 2014). The World Health Organization predicts that the three leading causes of death from injury worldwide—road traffic crashes, homicide, and suicide—will rise in rank compared to other leading causes of death. By 2030, road traffic crashes are predicted to rise from the ninth to the fifth leading cause of death (WHO, 2010).

Of course, the full burden of trauma is not confined to premature death; trauma also has enormous consequences in terms of disability and

__________________

7 Intentional injuries include suicide and homicide.

8 It should be noted, however, that the age of trauma patients is rising, a trend associated with falls among older adults.

9 This figure excludes deaths due to poisoning (51,966).

10 “Children” is defined here as anyone 18 years old or younger.

SOURCE: Data retrieved from NCIPC, 2015b.

future quality of life. In the military, injured patients are sustaining and surviving greater injuries than ever before, creating increased needs for acute, chronic, and rehabilitative care. Musculoskeletal injuries cause the majority of long-term disability associated with battlefield injuries, accounting for an estimated 69 percent of conditions resulting in unfit for duty determinations during the conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq (as determined by the U.S. Army Physical Evaluation Board during reviews of service members injured between 2001 and 2005) (Cross et al., 2011). Amputations contribute significantly to this burden. For example, while the rate of single amputation has remained constant, the percentage of amputees who have sustained multiple amputations during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq (30 percent) is much higher than in previous conflicts (Krueger et al., 2012). Moreover, traumatic brain injury (TBI) has been diagnosed in over 23,000 combat casualties from 2000 to 2013 (DVBIC, 2015). Although the major-

SOURCE: Data retrieved from NCIPC, 2015d.

ity of these injuries are typically classified as “mild TBI,” they have been associated with symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and other psychological conditions, and have significant implications for the quality of life of those injured and for their loved ones. Hoge and colleagues (2008) determined that PTSD was strongly associated with mild TBI: 43.9 percent of service members who reported loss of consciousness and 27.3 percent of those with altered mental status screened positive for PTSD 3-4 months following a year-long deployment to Iraq, compared with 16.2 percent of injured soldiers without mild TBI (Hoge et al., 2008). Improvised explosive devices (IEDs) designed to maim in Afghanistan and Iraq also have increased the occurrence of genitourinary trauma; it has been estimated that more than 12 percent of war injuries involve this type of trauma (Woodward and Eggertson, 2010).

The burden of injury-related disability in the civilian sector is equally striking. Although outcomes vary, decrements in physical and psychosocial functioning are common following injury and can have significant lifelong consequences for the injured person and his or her family. The National Study on the Costs and Outcomes of Trauma (NSCOT), for example, found that of more than 2,700 injured adults evaluated 1 year postinjury,

20.7 percent screened positive for PTSD, and 6.6 percent showed signs of depression. Nearly one-half (44.9 percent) of those working before incurring their injury had not yet returned to work at 1 year (Zatzick et al., 2008). As is true in the military, extremity trauma and TBI make the greatest contribution to the overall burden associated with nonfatal injuries.

Looking at financial costs, in 2013 injuries and violence cost $671 billion in medical care and lost productivity (Florence et al., 2015). Trauma affects the entire health care system, contributing significantly to the rising cost of health care in America. Each year, it accounts for 41 million emergency department visits and 2.3 million hospital admissions (NTI, 2014). In 2012, trauma-related conditions were the most costly for adults ages 18-64, accounting for $56.7 billion in health care expenditures; across all ages, trauma-related conditions consistently rank among the top four most costly conditions (Soni, 2015). Thus, despite the characterization of trauma as the “neglected epidemic of modern society” in a 1966 National Research Council report (NRC, 1966, p. 5) and numerous calls to action since that time, the economic and societal burden of trauma throughout the world represents an ongoing and increasing public health crisis.

Trauma morbidity and mortality statistics convey clearly that the vast majority of the burden of trauma is borne by the civilian population. Since 2001, there have been approximately 2 million U.S. civilian deaths from trauma11 (NCIPC, 2015b). In the same period, approximately 6,850 U.S. service members have died in theater (DCAS, 2016). Given this burden, as well as the military’s success in reducing trauma deaths and advancing rehabilitative care, the civilian sector has much to gain from the translation of military best practices in trauma care. Critical among these lessons learned is that, in many cases, even severe traumatic injuries are survivable with optimal delivery of trauma care in the context of a proper support system. The expectation of survivability after traumatic injury seen in the military, however, has not permeated the American public at large.

The Importance of Readiness to Deliver High-Quality Trauma Care

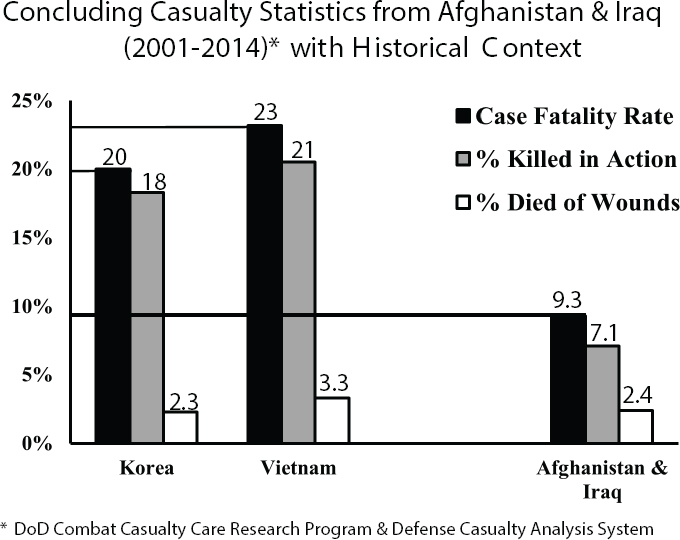

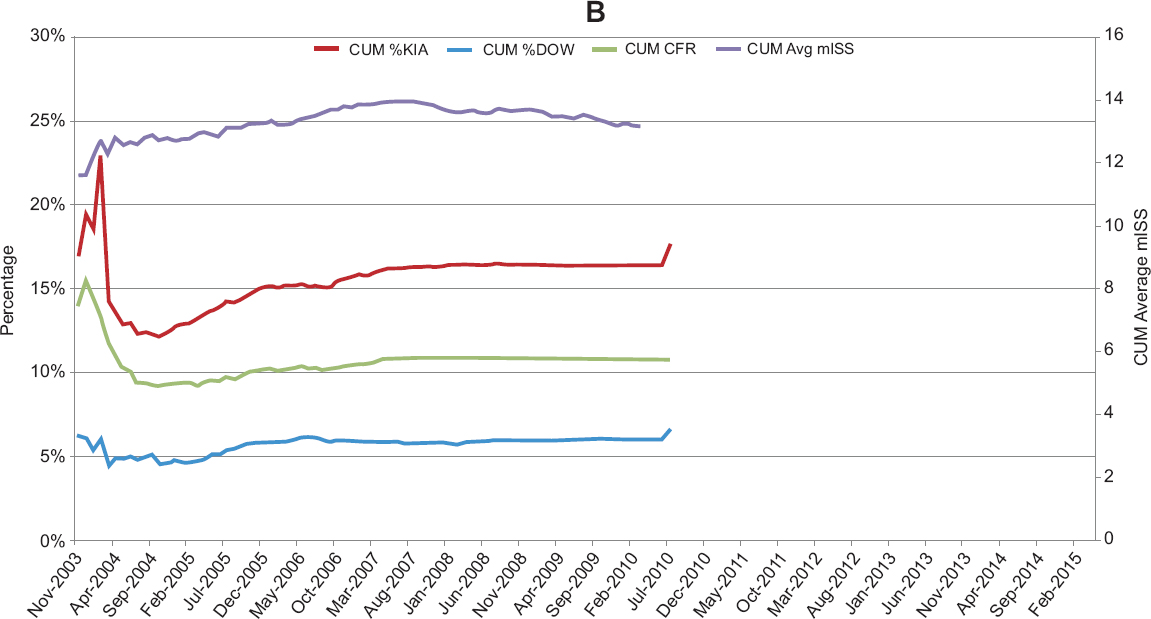

The impressive results in advancing trauma care achieved by the military since the start of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq include unprecedented survival rates for casualties arriving at a military treatment facility, reaching as high as 98 percent (Kotwal et al., 2013). As shown in Figure 1-3, the CFR in combat operations of the 21st century has been reduced by more than half compared with that during the Vietnam War (Lenhart et al., 2012). The percent killed in action (KIA) has been reduced to one-third

__________________

11 This figure excludes deaths due to poisoning, which are classified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as injury-related deaths, over the same time period (536,018).

NOTES: The statistics presented in this figure were calculated using data collected from the Defense Casualty Analysis System (DCAS), not from the DoD Trauma Registry. In calculating percent killed in action and percent died of wounds, the number of wounded individuals returned to duty (RTD) was not subtracted from the total number of wounded service members because RTD data are not collected in DCAS.

SOURCE: Proceedings of 2014 Military Health System Research Symposium, 2015.

of Vietnam levels, while the percent who died of their wounds (DOW) after reaching a military treatment facility has remained level, indicating that gains have been achieved primarily in the prehospital environment (see Box 1-4 for definitions of combat casualty care statistics). Factors influencing this improved survivability relative to previous conflicts likely include advances in personal protective equipment (e.g., body armor), differences in enemy tactics, the development of a mature deployed trauma system, and improved training based on the concepts of tactical combat casualty care. Congruent with these observations are data from Eastridge and colleagues (2012) showing that deaths due to peripheral extremity hemorrhage decreased from 23.3 deaths per year prior to 2006 to 3.5 deaths per year by 2011, which the authors associate with the military-wide fielding of tourniquets over the course of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Despite these accomplishments, however, gaps in capabilities and opportunities to improve care remain, particularly in the prehospital setting. Between 2001 and 2011, 87.3 percent of military battlefield fatalities occurred before those wounded reached a combat hospital. As noted above, although the vast majority of these deaths were caused by nonsurvivable injuries, hundreds of these service members might have survived12 if optimal trauma care had been delivered (Eastridge et al., 2012) (see Figure 1-4). Although the number of casualties who died of their wounds after reaching the hospital was much smaller, more than 50 percent of those deaths occurred from injuries that were potentially survivable (Eastridge et al., 2011).

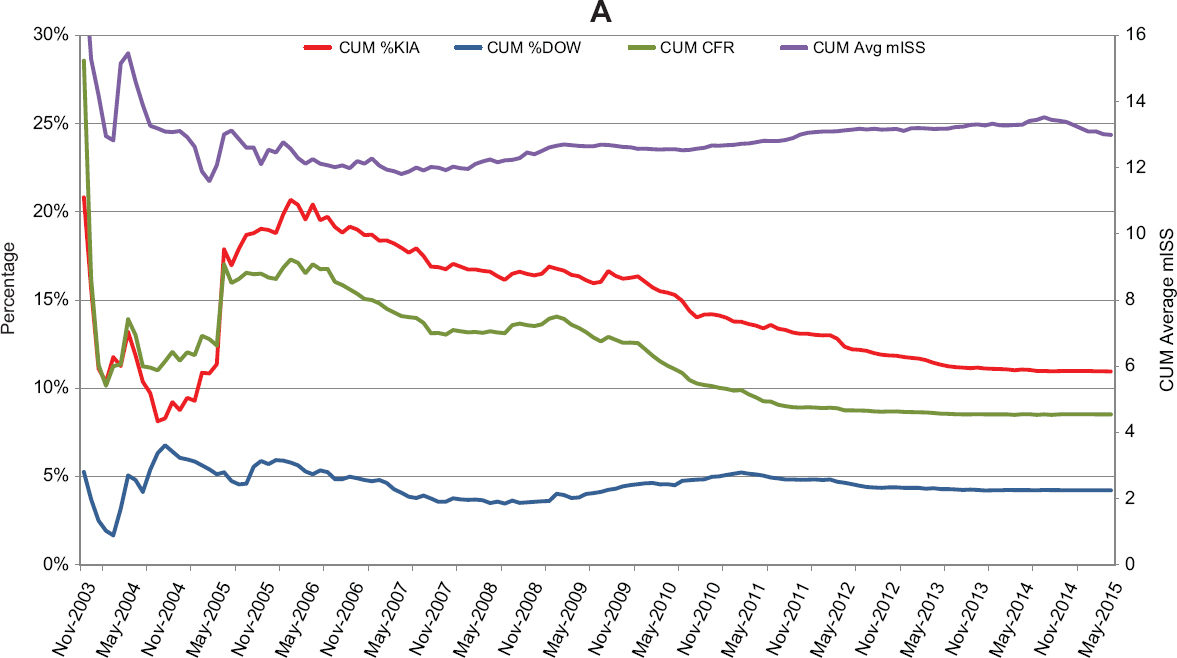

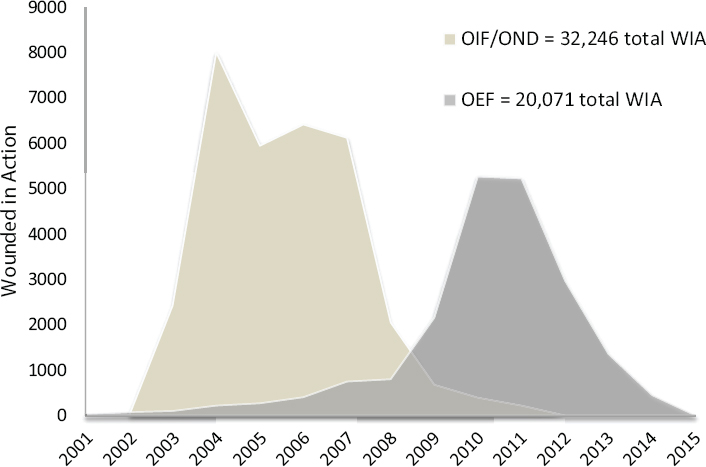

The CFR data shown in Figure 1-5 for Afghanistan (A) and Iraq (B) demonstrate variability in the military’s ability to care for an injured soldier over time and across the two theaters of war. CFR data from Operation Enduring Freedom, which closely follow the trends of the KIA data while the percent DOW remains relatively level, suggest the earlier-noted improvements in prehospital care and evacuation capabilities in the period between 2005 and 2015. This finding is consistent with a recent report by Kotwal and colleagues (2016) noting a statistically significant reduction in percent KIA and CFR following a 2009 mandate from the Secretary of Defense that prehospital helicopter transport of critically injured combat casualties occur within 60 minutes of injury or less. Median transport times (from call to arrival at the treatment facility) decreased from 90 to 43 minutes following that mandate. The reasons for the relatively flat DOW, KIA, and CFR rates over time in Iraq are not clear, but differences in timing between the two engagements are a likely partial explanation. The vast majority of combat-related injuries occurred in Iraq between 2003 and 2008 (see Figure 1-6), a period when DoD’s trauma system was still maturing. Making comparisons across the two theaters also is difficult as the terrain, enemy tactics, and distribution of medical assets differed considerably. Notably, the number of casualties increased significantly in Afghanistan starting in 2009, but the CFR and percent KIA continued to decrease.

An important emphasis of this report is that sustaining and building upon the advances in military trauma care achieved over the past decade are essential to ensuring medical readiness so that the military has the capability to provide optimal care for the very first injured soldier in the next conflict, whenever and wherever it may occur. It is not clear, however, that the military’s broader health system can support the continued level of excellence in trauma care delivered at the peak of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq without substantial commitment from leadership and change in

__________________

12 Survivability determinations were based on medical information only and did not take into account resource restrictions or operational conditions that may have prevented timely access to medical care (Eastridge et al., 2012).

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission of Dow Jones Company, from Are U.S. soldiers dying from survivable wounds? Phillips, M. M., Wall Street Journal, 2014; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

the processes by which a ready medical force is delivered. As the committee heard from General Peter Chiarelli, former Vice Chief of Staff for the U.S. Army, during its July 2015 meeting:

We are going to repeat the same mistakes we have made before. We are going to think our doctors are trained. They are not going to be trained. You have just got to pray your son or daughter or granddaughter is not the first casualty of the next war. Pray they come in at about the year five mark. (Chiarelli, 2015)

Beyond their benefits to the military sector, the rapid advances in trauma care capability achieved in wartime can yield crucial benefits in civilian settings. The effective translation of advances in care—for example, in hemorrhage control, damage control resuscitation, and the development of cutting-edge prosthetic and orthotic devices—from the military to the civilian sector can benefit not only trauma care provided on a daily basis but also that provided during and after mass casualty incidents. The increasing incidence of civilian trauma resembling that seen on the battlefield

SOURCE: Joint Trauma System. Data retrieved from the DoD Trauma Registry.

NOTES: Data were retrieved from the Defense Casualty Analysis System (DCAS). OEF = Operation Enduring Freedom; OIF = Operation Iraqi Freedom; OND = Operation New Dawn; WIA = wounded in action.

attests to the importance of this translation and demonstrates the extent to which lessons learned by the military can be applied in responding to mass casualty incidents in civilian settings (Elster et al., 2013b). The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) reports that between 2000 and 2013, there were 1,043 casualties from mass shootings in the United States (Blair and Schweit, 2014). According to a December 2, 2015, New York Times article, there were more days with than without a mass shooting13 in the United States in 2015 (LaFraniere et al., 2015). The value of military trauma care practices applied to domestic mass casualty incidents is highlighted by the success of the medical response following the Boston Marathon bombing (see Box 1-5).

At the same time, however, it should be emphasized that the most substantial benefit of military lessons learned in trauma care to the civilian sector is the prevention of deaths that occur every day from injuries that, given state-of-the-art trauma care capabilities, should not be fatal. Although mass casualty incidents are horrifying and tragic, a verified Level I

__________________

13 Mass shooting was defined as wounding or killing four or more people.

trauma center in the United States will see on average two to three times that many trauma patients in a single year (ACS, 2015) (equating to approximately 27,000 to 40,000 trauma patients in the same 13-year period that saw the 1,043 casualties from mass shootings reported by the FBI). Yet despite the clear importance of a domestic trauma response capability, no systematic processes have been instituted to ensure that the lessons learned from military experience are translated comprehensively to the civilian sector (Hunt, 2015).

A Brief But Critical Window of Opportunity

The military medical force of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq is the most experienced and successful medical force the military has produced in its long history (Mullen, 2015). Over the course of these two wars, military medicine was transformed. The sense of urgency stemming from deaths on the battlefield drove trauma care practices to evolve to a new level of excellence, and the resulting military medical force represents an enormous store

of knowledge and experience. The unfortunate reality facing the military, however, is that the window of opportunity to tap into this pool of knowledge is brief. Already, many of the leaders who enabled this military medical transformation and who serve as advocates for its perpetuation are retiring or transitioning to the civilian sector. In 5-10 years, a substantial number will be gone (Mullen, 2015). Wars and domestic mass casualty incidents will surely occur in the future, but with this loss of institutional memory, the question is how the sense of urgency to continuously improve trauma care and save lives can be sustained. Several recent reports and articles (discussed further in Chapter 7) offer recommendations for achieving the systematic preservation and transferal of military lessons learned, at both the systems and clinical care levels, so they can be leveraged and built upon to advance trauma care capabilities (Butler et al., 2015; DHB, 2015; Kotwal et al., 2013; Maldon et al., 2015; Rotondo et al., 2011; Sauer et al., 2014). In developing this report, the committee built on the insightful analyses and recommendations of these previously convened expert groups.

A Vision for Optimal Trauma Care

Maximum survivability and optimal quality of life and health after trauma depend on efficient and effective health care delivery from the point of injury to rehabilitation and beyond, supported by an overarching system that encompasses performance improvement, continual learning, research, education, and training. For the United States, this vision for trauma care can best be achieved when the military and civilian trauma systems coordinate, continually learning from each other and striving to improve. Capitalizing on lessons learned at the patient level, in capability development, and in system design and quality improvement within both sectors makes sense; would help appropriately address the burden of disease; would leverage economies of scale to save lives through trauma care; and would prepare the nation to provide optimal care for daily trauma events, as well as those occurring on the battlefield and during mass casualty incidents.

The 75th Ranger Regiment, an element of U.S. Army Special Operations Command, exemplifies how a commitment to the principles of a learning system can significantly reduce and even eliminate deaths from potentially survivable wounds. From 2001 to 2010, DoD-wide KIA and DOW statistics were 16.4 and 5.8 percent, respectively. In this same period, the 75th Ranger Regiment achieved markedly better outcomes—10.7 percent KIA and 1.7 percent DOW. Most impressively, while the greater U.S. military population faced a preventable death rate of up to 25 percent, the 75th Ranger Regiment documented only one potentially survivable fatality in the hospital setting and no preventable deaths in the prehospital setting (Kotwal et al., 2011).

These remarkable accomplishments are attributable largely to the regiment’s casualty care system, a program characterized by command ownership, comprehensive tactical combat casualty care (TCCC) training, data collection, and continual process improvement (Kotwal et al., 2011, 2013; Mabry, 2015). The regiment’s line commander at the time, then Colonel Stanley McChrystal,14 took complete ownership of the unit’s casualty care system, issuing a directive that all Rangers focus on medical training as one of the regiment’s four major training priorities (placing combat casualty care on a par, for example, with marksmanship) (Kotwal et al., 2011; Mabry, 2015). Colonel McChrystal’s leadership was a driving force in ensuring that tactical leaders assumed responsibility for the casualty response system and that all unit personnel were thoroughly trained in TCCC—a framework and set of continuously updated guidelines focused on treating life-threatening injuries in the prehospital setting while taking the tactical (nonmedical) situation into account (Kotwal et al., 2013; Mabry, 2015). This integration of TCCC into line command responsibilities was unique within DoD, which traditionally has left medical care to medical providers, with little input from tactical leaders (Kotwal et al., 2011). The regiment also independently established and utilized a unique Ranger Casualty Card and prehospital trauma registry to capture data historically challenging to collect, providing the continuous feedback necessary for performance improvement throughout the unit (Blackbourne et al., 2012; Kotwal et al., 2011). The critical decision of commanders to provide Rangers with the knowledge, training, and equipment to render immediate care, when linked to an effective joint theater trauma system featuring coordinated evacuation sequences and patient handoffs across the trauma care continuum, led to an unprecedented reduction in preventable deaths and the greatest survival record in the history of war.

A central message of this report is the importance of significantly greater integration of the U.S. military and civilian trauma systems to achieve the goal of zero preventable trauma deaths, regardless of where (e.g., urban or rural) and when (e.g., at the start or the end of a war) an injury occurs. In the pursuit of this goal, the 75th Ranger Regiment serves as an exemplar for all, demonstrating how an integrated trauma system with strong leadership and continuous feedback and improvement (i.e., a learning trauma care system) can dramatically improve trauma outcomes. Others have already taken up this cause. In response to the demonstrated success of the 75th Ranger Regiment, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) Medical Corps set a goal of eliminating preventable deaths across all branches and services of the IDF and developed a plan for achieving this goal (Glassberg et al., 2014). Execution of this plan—called “My Brother’s Keeper”—began with

__________________

14 McChrystal later achieved the rank of General.

engaging line commanders in a commitment to this goal, incorporating the concept into all command training and education programs, and reinforcing collaborations with Israeli civilian health system and international partners. Progress toward the goal will be monitored through continuous analysis of casualty data in the IDF Trauma Registry, use of which will help in refining equipment, doctrine, and training over time.

By extrapolating from the outcomes of best-in-class trauma care systems, it is possible to estimate the societal benefit that could be achieved through the uniform provision of high-quality trauma care. Had care at the level achieved by the 75th Ranger Regiment been provided throughout the military during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq instead of being confined to one regiment, hundreds of service members who perished in the line of duty over the course of a decade might have survived. In the civilian sector, one estimate is that nearly 20,000 Americans could be saved each year if all trauma centers achieved outcomes similar to those at the highest-performing centers (Hashmi et al., 2016), a figure that equates to 200,000 trauma deaths prevented in that same 10-year period.15 Concerted efforts aimed at establishing the type of learning trauma care system developed by the 75th Ranger Regiment and other best-in-class trauma systems will be essential to improving trauma care in both the military and civilian contexts. A framework for such a learning trauma care system is described in Chapter 3.

In light of trauma’s profound burden and the increasing threats to homeland security, improving the nation’s military and domestic trauma response capability is a national imperative. Deliberate steps to codify and harvest the lessons learned within the military’s trauma care system are needed to ensure a ready military medical force for future combat and to eliminate preventable trauma deaths and disability after injury in both the military and civilian sectors. The end of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq represents a unique moment in history in that there now exists a nascent military trauma system built on a learning system framework and an organized civilian trauma system that is well positioned to assimilate and distribute the recent wartime trauma lessons learned and to serve as a repository and an incubator for innovation in trauma care during the interwar period. Together, these two developments present an opportunity to integrate military and civilian trauma systems, thereby ensuring continuous bidirectional learning. To this end, unprecedented partnership across mili-

__________________

15 This estimate takes into account only improvements in in-hospital care. There is no equivalent estimate for the number of lives that could potentially be saved from simultaneous improvements in prehospital care. In one metropolitan jurisdiction, analysis of medical examiner reports indicated that nearly 30 percent of prehospital trauma deaths resulted from potentially survivable injuries, and of these, 64.4 percent were at least in part attributable to hemorrhage (Davis et al., 2014).

tary and civilian sectors and a sustained commitment from trauma system leaders at all levels will be required to ensure that this knowledge and these tools are not lost. Lives hang in the balance.

CHARGE TO THE COMMITTEE AND STUDY SCOPE

Study Origin and Charge to the Committee

Concerned that the lessons learned from military wartime experience have not been translated to the civilian sector in a comprehensive or systematic fashion, Richard Hunt, then director for medical preparedness policy for the White House National Security Council, engaged in discussions with the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine in 2014, indicating that a study on this topic would be “of interest and of benefit to the nation” (Hunt, 2015), as well as complementary to a concurrent White House effort on bystander interventions for life-threatening traumatic hemorrhage.16 In 2015, the Committee on Military Trauma Care’s Learning Health System and Its Translation to the Civilian Sector was established with funding from three federal agencies (DoD’s Medical Research and Materiel Command, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Health Affairs, and the U.S. Department of Transportation’s (DOT’s) National Highway Traffic Safety Administration) and five professional organizations (the American College of Emergency Physicians, American College of Surgeons, National Association of Emergency Medical Services Physicians, National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians, and Trauma Center Association of America). This group of sponsors, representing both the military and civilian sectors, asked the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to conduct a consensus study to define the components of a learning health system necessary to enable continued improvement in trauma care in both the civilian and military sectors, and to provide recommendations for ensuring that lessons learned over the past decade from the military’s experiences in Afghanistan and Iraq will be sustained and built upon for future combat operations, as well as translated to the U.S. civilian system. The full charge to the committee is presented in Box 1-6.

To respond to this charge, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine convened a committee comprising experts in each element of the spectrum of trauma care, as well as military medicine and combat casualty care, pediatrics, bioethics, competency-based medicine,

__________________

16 On October 6, 2015, the White House launched the “Stop the Bleed” campaign to provide people with the knowledge and tools to save lives by stopping life-threatening hemorrhage during an emergency prior to the arrival of emergency medical personnel (White House, 2015).

learning health care systems, information systems, comparative effectiveness research, health services research, delivery and financing of health care, clinical guideline development, and medical education and training. Biographies of the committee members are presented in Appendix F.

Study Scope

As specified in its statement of task, the committee was charged with evaluating trauma care in its acute phase only, starting at the point of injury and ending at the transition to rehabilitation. Although the committee recognizes and acknowledges that prevention and rehabilitation both play critically important roles in reducing the burden of traumatic injury and improving later quality of life, these components were intentionally excluded from the committee’s scope of work. Still, the committee believes it is important to emphasize that the full continuum of trauma care extends from prevention to rehabilitation and reintegration into society. Indeed, the best strategy to eliminate deaths from trauma is to prevent injuries from occurring in the first place. Although primary prevention strategies are not discussed in any depth in the present report, the committee notes that previous reports have addressed this important topic (see Box 1-7) and many resources are available through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (http://www.cdc.gov/injury). Similarly, the committee did not conduct an evaluation of systems and best practices for rehabilitation in military and civilian settings but instead refers readers to a number of previous reports that have addressed this topic (see Box 1-7). That said, it is important to recognize that care delivered in the acute phase has significant implications for later rehabilitation; improved acute care and reduced mortality will certainly increase the need for robust rehabilitation support to ensure quality of life. Further, long-term outcome data captured during rehabilitation and post-acute care (e.g., quality of life, level of function, and other patient-centered outcomes) are of critical importance to acute-phase providers in a learning system to inform continuous quality improvement activities (as discussed in more detail in Chapter 4). With this in mind, elements related to rehabilitation are mentioned where appropriate throughout this report.

While not explicitly excluded from the scope of work for this study, an examination of methods to diagnose, prevent, and treat PTSD and other mental health disorders associated with physical trauma was considered by the committee as an expansion of scope that could not have been addressed in a comprehensive way given the committee’s limited time and resources. However, recognizing the importance of early screening and intervention during the acute-care phase to prevent or mitigate downstream mental health sequelae of physical trauma, these issues are addressed in the con-

text of holistic trauma patient care in Chapter 6. Relevant reports are also noted in Box 1-7.

The committee also acknowledges that trauma care is just one aspect of a far larger emergency care system, and although an analysis of that broader system is beyond the scope of this report,17 the committee included in its deliberations the impacts of its recommendations on the overall emer-

__________________

17 The emergency care system was the focus of the Future of Emergency Care series of Institute of Medicine reports released in 2007. The committee looked to these resources in developing its recommendations with respect to trauma care.

gency care system in hopes that steps taken to improve trauma care will have the added value of reducing preventable deaths and disability associated with other acute, time-sensitive conditions.

The primary charge to the committee was to focus on the military’s trauma system and research investment, as well as the bidirectional translation of lessons learned and best trauma care practices between the military and civilian sectors. Although the committee was not tasked with evaluating the civilian sector independently, it did learn about civilian trauma systems in the course of its information gathering and comments on the civilian sector in this report as it relates to the sustainment of military advances in trauma care and opportunities for improved translation between the military and civilian sectors.

STUDY APPROACH

Study Process

During the course of its deliberations, the committee sought information through a variety of mechanisms. These mechanisms included a series of information-gathering meetings that were open to the public, including a public workshop held to obtain background information on leadership and accountability, trauma data and information systems, clinical guideline development, and military education and training for readiness. A second meeting, held in September 2015, included two additional information-gathering sessions, the first of which focused on ethics and regulatory issues that influence a learning system, and the second of which addressed the burden of injury and trauma research investment in the military and civilian sectors. During the course of the September 2015 meeting, the committee also participated in the military’s JTS Video Teleconference, a weekly worldwide trauma conference held to discuss the previous week’s military trauma cases. In addition, the committee held a series of Web-based meetings in which it heard from experts in civilian emergency medical services, trauma nursing, and military leadership. Agendas for these meetings can be found in Appendix E.

The committee gathered additional information by reviewing the peer-reviewed and gray literature. The committee also requested documents and information from DoD, DOT, HHS, and other trauma stakeholder organizations to better inform its deliberations, and received materials submitted by members of the public for its consideration throughout the course of the study.18 Finally, the committee commissioned papers on (1) cur-

__________________

18 A list of materials submitted to the committee’s public access file can be requested from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s Public Access Records Office.

rent military–civilian exchange practices, and (2) the collection and use of trauma data. Key excerpts from these papers are included in Appendixes C and D, respectively, and the papers are available in their entirety on the study’s website.19

Case Studies

In accordance with its statement of task, the committee’s conclusions and recommendations were informed by case studies focused on combat-related injuries, many of which are commonly encountered in the civilian setting as well. These case studies include the following traumatic injuries: extremity hemorrhage, blunt trauma with vascular injury, pediatric burn, dismounted complex blast injury, and severe TBI. Because the committee lacked direct access to medical case histories for U.S. service members wounded on the battlefield, the case studies were initially authored by DoD personnel and submitted to the committee for review. The committee invited input from all of the study sponsors on the cases’ format and content and requested additional information from DoD using a standardized template created for this purpose. The case studies were then further developed through an iterative process of revision and review (see Appendix A). Each case study offers insight into the military’s learning process for trauma care, illustrating specifically, for example, the levels of evidence used to develop clinical guidelines and the processes by which patient and injury information was collected, stored, reviewed, and analyzed by the JTS. In doing so, these cases reveal gaps that remain in the military trauma system and facilitate consideration of how best to translate advances in trauma care to the civilian sector. A committee-generated collective analysis of the case studies is presented in Appendix B. Throughout this report, the committee uses boxes drawing from these case studies to demonstrate the opportunities and challenges of establishing a learning trauma care system.

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

This report is organized into three parts that collectively define a learning trauma care system necessary to sustain and build on the recent advances in military trauma care and to facilitate continuous bidirectional translation of trauma care advances between the military and civilian sectors. Part I of the report includes Chapters 1 through 3. Chapter 2 provides an overview of the essential elements of a trauma system and their application in the military and civilian trauma systems. That chapter also outlines the existing mechanisms by which the military and civilian systems interface

__________________

for bidirectional translation. Chapter 3 presents a framework for a learning trauma care system, drawing on the components of a learning health system as articulated by the Institute of Medicine (2013) report Best Care at Lower Cost and applying those components to a trauma care system. Using this framework, Part II assesses the strengths and gaps in the military and, at the national level, civilian trauma systems, focusing specifically on generating and applying knowledge to improve trauma outcomes (Chapter 4), creating and sustaining an expert trauma care workforce (Chapter 5), delivering patient-centered trauma care (Chapter 6), and leveraging leadership and fostering a culture of learning (Chapter 7). Each of these four chapters ends with a summary of key findings and the committee’s conclusions in the respective topics. While focusing on the military sector, these chapters do provide a general overview of civilian-sector differences to highlight areas in which the structure and processes of the civilian sector impact military sustainment of trauma care advances and bidirectional translation of lessons learned and best practices between the two sectors. The final part of this report, Chapter 8, highlights the committee’s key messages—particularly the need for an integrated national approach to trauma care—and concludes with recommendations on advancing a national learning trauma care system.

REFERENCES

ACS (American College of Surgeons). 2015. National Trauma Data Bank 2015: Annual report. Chicago, IL: ACS.

Andersen, R. C., S. B. Shawen, J. F. Kragh, Jr., C. T. Lebrun, J. R. Ficke, M. J. Bosse, A. N. Pollak, V. D. Pellegrini, R. E. Blease, and E. L. Pagenkopf. 2012. Special topics. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 20(Suppl. 1):S94-S98.

Bailey, J., M. A. Spott, G. P. Costanzo, J. R. Dunne, W. Dorlac, and B. J. Eastridge. 2012a. Joint Trauma System: Development, conceptual framework, and optimal elements. San Antonio, TX: Fort Sam Houston, U.S. Department of Defense, U.S. Army Institute for Surgical Research.

Bailey, J., S. Trexler, A. Murdock, and D. Hoyt. 2012b. Verification and regionalization of trauma systems: The impact of these efforts on trauma care in the United States. Surgical Clinics of North America 92(4):1009-1024, ix-x.

Bailey, J. A., J. J. Morrison, and T. E. Rasmussen. 2013. Military trauma system in Afghanistan: Lessons for civil systems? Current Opinion in Critical Care 19(6):569-577.

Bellamy, R. F. 1984. The causes of death in conventional land warfare: Implications for combat casualty care research. Military Medicine 149(2):55-62.

Biddinger, P. D., A. Baggish, L. Harrington, P. d’Hemecourt, J. Hooley, J. Jones, R. Kue, C. Troyanos, and K. S. Dyer. 2013. Be prepared—the Boston Marathon and mass-casualty events. New England Journal of Medicine 368(21):1958-1960.

Blackbourne, L. H., D. G. Baer, B. J. Eastridge, F. K. Butler, J. C. Wenke, R. G. Hale, R. S. Kotwal, L. R. Brosch, V. S. Bebarta, M. M. Knudson, J. R. Ficke, D. Jenkins, and J. B. Holcomb. 2012. Military medical revolution: Military trauma system. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 73(6 Suppl. 5):S388-S394.

Blair, J. P., and K. W. Schweit. 2014. A study of active shooter incidents, 2000-2013. Washington, DC: Texas State University and Federal Bureau of Investigation, U.S. Department of Justice.

Branas, C. C., E. J. MacKenzie, J. C. Williams, C. W. Schwab, H. M. Teter, M. C. Flanigan, A. J. Blatt, and C. S. ReVelle. 2005. Access to trauma centers in the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association 293(21):2626-2633.

Brown, J. 2015. Trauma research investment. Paper presented to the Committee on Military Trauma Care’s Learning Health System and Its Translation to the Civilian Sector, Meeting Three, September 16-17, Washington, DC.

Butler, F. K., Jr., and L. H. Blackbourne. 2012. Battlefield trauma care then and now: A decade of tactical combat casualty care. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 73(6 Suppl. 5):S395-S402.

Butler, F. K., Jr., J. H. Hagmann, and D. T. Richards. 2000. Tactical management of urban warfare casualties in special operations. Military Medicine 165(Suppl. 1):1-48.

Butler, F. K., D. J. Smith, and R. H. Carmona. 2015. Implementing and preserving the advances in combat casualty care from Iraq and Afghanistan throughout the US military. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 79(2):321-326.

Chiarelli, P. W. 2015. MCRMC health care recommendations summary. Paper presented at the Committee on Military Trauma Care’s Learning Health System and Its Translation to the Civilian Sector, Meeting Two, July 23-24, Washington, DC.

Churchill, E. D. 1952. Introduction. In The board for the study of the severely wounded: The physiologic effects of wounds, edited by H. K. Beecher. Washington, DC: Office of the Surgeon General. Pp. 1-20.

Churchill, E. D. 1972. Surgeon to soldiers. Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott Company.

Cross, J. D., J. R. Ficke, J. R. Hsu, B. D. Masini, and J. C. Wenke. 2011. Battlefield orthopaedic injuries cause the majority of long-term disabilities. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 19(Suppl. 1):S1-S7.

Davis, J. S., S. S. Satahoo, F. K. Butler, H. Dermer, D. Naranjo, K. Julien, R. M. Van Haren, N. Namias, L. H. Blackbourne, and C. I. Schulman. 2014. An analysis of prehospital deaths: Who can we save? Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 77(2):213-218.

DCAS (Defense Casualty Analysis System). 2016. Conflict casualties. https://www.dmdc.osd.mil/dcas/pages/casualties.xhtml (accessed June 9, 2015).

DeBakey, M. E. 1996. History, the torch that illuminates: Lessons from military medicine. Military Medicine 161(12):711-716.

DHB (Defense Health Board). 2015. Combat trauma lessons learned from military operations of 2001-2013. Falls Church, VA: DHB.

DoD (U.S. Department of Defense). 2016. Department of Defense dictionary of military and associated terms: Joint publication 1-02. Washington, DC: DoD.

DVBIC (Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center). 2015. Traumatic brain injury (TBI) awareness. Silver Spring, MD: DVBIC. https://dvbic.dcoe.mil/sites/default/files/DVBIC_TBI-Awareness_FactSheet_v1.0_2015-05-12.pdf (accessed March 7, 2016).

Eastman, A. B. 2010. Wherever the dart lands: Toward the ideal trauma system. Journal of the American College of Surgeons 211(2):153-168.

Eastman, A. B., E. J. MacKenzie, and A. B. Nathens. 2013. Sustaining a coordinated, regional approach to trauma and emergency care is critical to patient health care needs. Health Affairs 32(12):2091-2098.

Eastridge, B. J., M. Hardin, J. Cantrell, L. Oetjen-Gerdes, T. Zubko, C. Mallak, C. E. Wade, J. Simmons, J. Mace, and R. Mabry. 2011. Died of wounds on the battlefield: Causation and implications for improving combat casualty care. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 71(1):S4-S8.

Eastridge, B. J., R. L. Mabry, P. Seguin, J. Cantrell, T. Tops, P. Uribe, O. Mallett, T. Zubko, L. Oetjen-Gerdes, T. E. Rasmussen, F. K. Butler, R. S. Kotwal, J. B. Holcomb, C. Wade, H. Champion, M. Lawnick, L. Moores, and L. H. Blackbourne. 2012. Death on the battlefield (2001-2011): Implications for the future of combat casualty care. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 73(6 Suppl. 5):S431-S437.

Elster, E. A., F. K. Butler, and T. E. Rasmussen. 2013a. Implications of combat casualty care for mass casualty events. Journal of the American Medical Association 310(5):475-476.

Elster, E. A., E. Schoomaker, and C. Rice. 2013b. The laboratory of war: How military trauma care advances are benefiting soldiers and civilians. Health Affairs Blog. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2013/12/18/the-laboratory-of-war-how-military-trauma-care-advances-are-benefiting-soldiers-and-civilians (accessed May 21, 2015).

Florence, C., T. Simon, T. Haegerich, F. Luo, and C. Zhou. 2015. Estimated lifetime medical and work-loss costs of fatal injuries—United States, 2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 64(38):1074-1082.

Gates, J. D., S. Arabian, P. Biddinger, J. Blansfield, P. Burke, S. Chung, J. Fischer, F. Friedman, A. Gervasini, E. Goralnick, A. Gupta, A. Larentzakis, M. McMahon, J. Mella, Y. Michaud, D. Mooney, R. Rabinovici, D. Sweet, A. Ulrich, G. Velmahos, C. Weber, and M. B. Yaffe. 2014. The initial response to the Boston Marathon bombing: Lessons learned to prepare for the next disaster. Annals of Surgery 260(6):960-966.

Glassberg, E., R. Nadler, A. M. Lipsky, A. Shina, D. Dagan, and Y. Kreiss. 2014. Moving forward with combat casualty care: The IDF-MC strategic force buildup plan “My Brother’s Keeper.” Israel Medical Association Journal: IMAJ 16(8):469-474.

Gross, K. 2015. Joint Trauma System. Paper presented to the Committee on Military Trauma Care’s Learning Health System and Its Translation to the Civilian Sector, Meeting One, May 18-19, Washington, DC.

Hashmi, Z. G., S. Zafar, T. Genuit, E. R. Haut, D. T. Efron, J. Havens, Z. Cooper, A. Salim, E. E. Cornwell III, and A. H. Haider. 2016. The potential for trauma quality improvement: One hundred thousand lives in five years. http://www.asc-abstracts.org/abs2016/15-12-the-potential-for-trauma-quality-improvement-one-hundred-thousandlives-in-five-years (accessed February 21, 2016).

Hoge, C. W., D. McGurk, J. L. Thomas, A. L. Cox, C. C. Engel, and C. A. Castro. 2008. Mild traumatic brain injury in U.S. soldiers returning from Iraq. New England Journal of Medicine 358(5):453-463.

Holcomb, J. B., L. G. Stansbury, H. R. Champion, C. Wade, and R. F. Bellamy. 2006. Understanding combat casualty care statistics. Journal of Trauma 60(2):397-401.

Holcomb, J. B., N. R. McMullin, L. Pearse, J. Caruso, C. E. Wade, L. Oetjen-Gerdes, H. R. Champion, M. Lawnick, W. Farr, S. Rodriguez, and F. K. Butler. 2007. Causes of death in U.S. Special Operations Forces in the global war on terrorism: 2001-2004. Annals of Surgery 245(6):986-991.

Hunt, R. 2015. White House initiative on bystander interventions for life-threatening traumatic hemorrhage. Paper presented to the Committee on Military Trauma Care’s Learning Health System and Its Translation to the Civilian Sector, Meeting One, May 18-19, Washington, DC.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2013. Best care at lower cost: The path to continuously learning health care in America. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Kelly, J. F., A. E. Ritenour, D. F. McLaughlin, K. A. Bagg, A. N. Apodaca, C. T. Mallak, L. Pearse, M. M. Lawnick, H. R. Champion, C. E. Wade, and J. B. Holcomb. 2008. Injury severity and causes of death from Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom: 2003-2004 versus 2006. Journal of Trauma 64(Suppl. 2):S21-S26.

King, D. R., A. Larentzakis, and E. P. Ramly. 2015. Tourniquet use at the Boston Marathon bombing: Lost in translation. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 78(3):594-599.

Kotwal, R. S., H. R. Montgomery, B. M. Kotwal, H. R. Champion, F. K. Butler, Jr., R. L. Mabry, J. S. Cain, L. H. Blackbourne, K. K. Mechler, and J. B. Holcomb. 2011. Eliminating preventable death on the battlefield. Archives of Surgery 146(12):1350-1358.

Kotwal, R. S., F. K. Butler, E. P. Edgar, S. A. Shackelford, D. R. Bennett, and J. A. Bailey. 2013. Saving lives on the battlefield: A Joint Trauma System review of pre-hospital trauma care in Combined Joint Operating Area-Afghanistan (CJOA-A). https://www.naemt.org/docs/default-source/education-documents/tccc/10-9-15-updates/centcom-prehospitalfinal-report-130130.pdf?sfvrsn=2 (accessed January 13, 2015).

Kotwal, R. S., J. T. Howard, J. A. Orman, B. W. Tarpey, J. A. Bailey, H. R. Champion, R. L. Mabry, J. B. Holcomb, and K. R. Gross. 2016. The effect of a golden hour policy on the morbidity and mortality of combat casualties. JAMA Surgery 151(1):15-24.

Kotz, D. 2013. After double-checking records, injury toll from bombs reduced to 264. Boston Globe, April 24, B3.

Kragh, J. F., Jr., J. San Antonio, J. W. Simmons, J. E. Mace, D. J. Stinner, C. E. White, R. Fang, J. K. Aden, J. R. Hsu, B. J. Eastridge, D. H. Jenkins, J. D. Ritchie, M. O. Hardin, A. E. Ritenour, C. E. Wade, and L. H. Blackbourne. 2013. Compartment syndrome performance improvement project is associated with increased combat casualty survival. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 74(1):259-263.

Krueger, C. A., J. C. Wenke, and J. R. Ficke. 2012. Ten years at war: Comprehensive analysis of amputation trends. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 73(6 Suppl. 5):S438-S444.

Kwon, A. M., N. C. Garbett, and G. H. Kloecker. 2014. Pooled preventable death rates in trauma patients. European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery 40(3):279-285.

LaFraniere, S., S. Cohen, and R. A. Oppel. 2015. How often do mass shootings occur? On average, every day, records show. The New York Times, December 2. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/03/us/how-often-do-mass-shootings-occur-on-average-every-day-records-show.html?_r=1 (accessed January 19, 2016).

Lenhart, M. K., E. Savitsky, and B. Eastridge. 2012. Combat casualty care: Lessons learned from OEF and OIF. Falls Church, VA: Office of the Surgeon General, U.S. Department of the Army.

Lindsey, D. 1957. The case of the much-maligned tourniquet. American Journal of Nursing 57(4):444-445.

Mabry, R. L. 2015. Challenges to improving combat casualty survivability on the battlefield. Joint Force Quarterly 76(1):78-84.

Maldon, A., L. L. Pressler, S. E. Buyer, D. S. Zakheim, M. R. Higgins, P. W. Chiarelli, E. P. Giambastiani, J. R. Kerrey, and C. P. Carney. 2015. Report of the Military Compensation and Retirement Modernization Commission: Final report. Arlington, VA: Military Compensation and Retirement Modernization Commission.

Manring, M. M., A. Hawk, J. H. Calhoun, and R. C. Andersen. 2009. Treatment of war wounds: A historical review. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 467(8):2168-2191.

Mullen, M. 2015. The role of leadership in a learning trauma care system. Paper presented at the Committee on Military Trauma Care’s Learning Health System and Its Translation to the Civilian Sector, October 2, Washington, DC.

NCIPC (National Center for Injury Prevention and Control). 2015a. WISQARS™ fatal injury reports: 2014, United States, all injury deaths and rates per 100,000, all races, both sexes, ages 0 to 18. http://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/mortrate10_us.html (accessed March 4, 2016).

NCIPC. 2015b. WISQARS™ fatal injury reports: 2014, United States, all injury deaths and rates per 100,000, all races, both sexes, all ages. http://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/mortrate10_us.html (accessed March 4, 2016).

NCIPC. 2015c. WISQARS™ leading causes of death reports: 10 leading causes of death, 2014, United States, all races, both sexes. http://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/leadcaus10_us.html (accessed March 4, 2016).

NCIPC. 2015d. WISQARS™ years of potential life lost reports: Years of potential life lost (YPLL) before age 75, 2014, United States, all races, both sexes, all deaths. http://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/ypll10.html (accessed March 4, 2016).

Norton, R., and O. Kobusingye. 2013. Injuries. New England Journal of Medicine 368(18):1723-1730.

NRC (National Research Council). 1966. Accidental death and disability: The neglected disease of modern society. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

NTI (National Trauma Institute). 2014. Trauma statistics. http://nationaltraumainstitute.com/home/trauma_statistics.html (accessed September 11, 2015).

Peden, M., K. Oyegbite, J. Ozanne-Smith, A. A. Hyder, C. Branche, F. Rahman, F. Rivara, and K. Bartolomeos. 2008. World report on child injury prevention. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

Phillips, M. M. 2014. Are U.S. soldiers dying from survivable wounds? Wall Street Journal, September 19. http://www.wsj.com/articles/are-u-s-soldiers-dying-from-survivable-wounds-1411145160 (accessed December 15, 2014).

Proceedings of 2014 Military Health System Research Symposium. 2015. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 79(4):S61-S242.

Pruitt, B. A., Jr. 2008. The symbiosis of combat casualty care and civilian trauma care: 1914-2007. Journal of Trauma 64(Suppl. 2):S4-S8.

Rasmussen, T. E., K. R. Gross, and D. G. Baer. 2013. Where do we go from here. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 75(2 Suppl. 2):S105-S106.

Rhee, P., B. Joseph, V. Pandit, H. Aziz, G. Vercruysse, N. Kulvatunyou, and R. S. Friese. 2014. Increasing trauma deaths in the United States. Annals of Surgery 260(1):13-21.

Richey, S. L. 2007. Tourniquets for the control of traumatic hemorrhage: A review of the literature. World Journal of Emergency Surgery 2:28.

Rotondo, M., T. Scalea, A. Rizzo, K. Martin, and J. Bailey. 2011. The United States military Joint Trauma System assessment: A report commissioned by the U.S. Central Command Surgeon, sponsored by Air Force Central Command, a strategic document to provide a platform for tactical development. Washington, DC: DoD.

Santayana, G. 1905. The life of reason: Reason in common sense. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Sauer, S. W., J. B. Robinson, M. P. Smith, K. R. Gross, R. S. Kotwal, R. Mabry, F. K. Butler, Z. T. Stockinger, J. A. Bailey, M. E. Mavity, and D. A. Gillies. 2014. Saving lives on the battlefield (Part II)—one year later: A Joint Theater Trauma System & Joint Trauma System review of pre-hospital trauma care in Combined Joint Operating Area-Afghanistan (CJOA-A). http://www.naemsp.org/Documents/E-News%20-%20loaded%20docs%20for%20link/Saving%20Lives%20on%20the%20Battlefield%20II.pdf (accessed January 13, 2015).

Schwab, C. W. 2015. Winds of war: Enhancing civilian and military partnerships to assure readiness: White paper. Journal of the American College of Surgeons 221(2):235-254.

Soni, A. 2015. Statistical brief #471: Top five most costly conditions among adults age 18 and older, 2012: Estimates for the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population. http://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_files/publications/st471/stat471.shtml (accessed March 1, 2016).

Trunkey, D. D. 1983. Trauma. Scientific American 249(2):28-35.

Trunkey, D. D. 2000. History and development of trauma care in the United States. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 374(2):36-46.

Walters, T. J., D. S. Kauvar, D. G. Baer, and J. B. Holcomb. 2005. Battlefield tourniquets: Modern combat lifesavers. Army Medical Department Journal 42-43.

White House. 2015. Don’t be a bystander: Find out how you can “stop the bleed.” https://www.whitehouse.gov/blog/2015/10/06/stop-bleed (accessed February 17, 2016).

WHO (World Health Organization). 2010. Injury and violence: The facts. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

Woodward, C., and L. Eggertson. 2010. Homemade bombs and heavy urogenital injuries create new medical challenges. Canadian Medical Association Journal 182(11):1159-1160.

Zatzick, D., G. J. Jurkovich, F. P. Rivara, J. Wang, M. Y. Fan, J. Joesch, and E. MacKenzie. 2008. A national US study of posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and work and functional outcomes after hospitalization for traumatic injury. Annals of Surgery 248(3):429-437.