2

Existing Studies and Data

THE TRAUMA MODULE IN THE MENTAL HEALTH SURVEILLANCE STUDY

Rhonda Karg (RTI International) discussed the measures of trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress symptoms included in the Mental Health Surveillance Study (MHSS), conducted as a follow-on to the National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) between 2008 and 2012, and she described the estimates that can be produced on the basis of these data.

The MHSS included the Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (SCID), which Karg said is used by several studies as the “gold standard” in determining the accuracy of clinical diagnoses. The SCID is a semi-structured interview, which allows for flexibility in probing, as necessary, and it requires clinical judgment to make a diagnostic decision. Each SCID symptom is rated as 1, absent; 2, subclinical; 3, present; and ?, need more information. For some analyses in the MHSS, the ? and 2 codes were recoded as 1. A minimum number of symptoms must be present (coded as 3), to meet diagnostic criteria, and the number of symptoms needed depends on the disorder.

The SCID includes screening items for certain disorders, including PTSD. The screening items typically assess the first criterion for the respective disorder. They also help to prevent respondents from “faking good” if they later realize that answering “no” shortens the interview, and they help the clinical interviewer estimate how long the interview will be.

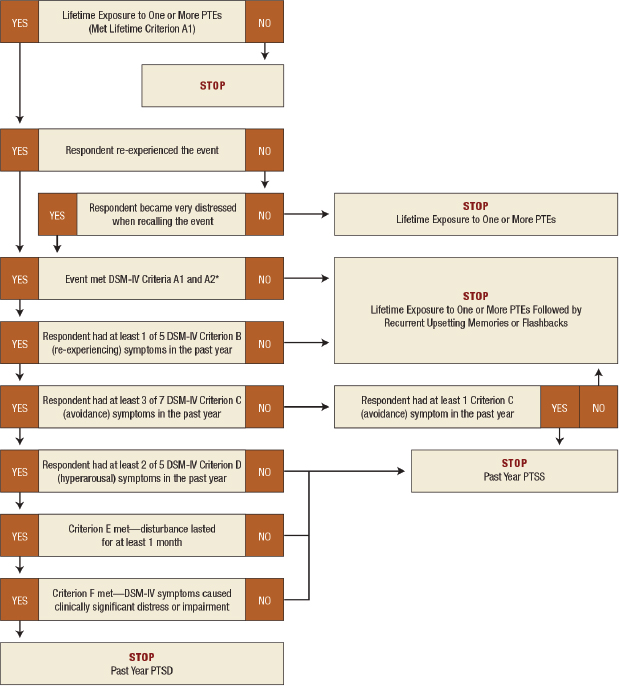

Karg said that the SCID assessment of PTSD was according to the

fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Text Revised (DSM-IV-TR) PTSD diagnostic criteria. The screening was for lifetime trauma exposure, in combination with questions about whether the respondent re-experienced the traumatic event or became very distressed when recalling the traumatic event. If this screening yielded a positive result, the SCID was administered for the past year, until the criteria were no longer met. The study used the standard version of the SCID, which skips follow-up questions at the point at which the criteria are no longer met, rather than administering all questions to everyone, as is sometimes done in studies where responses to particular symptoms may be of interest. If a respondent reported having experienced more than one traumatic event, clinical judgment was used to decide which one to refer to in the follow-up questions about the outcome of the traumatic event.

For background, Karg provided an overview of the diagnostic criteria for trauma in the DSM-IV-TR. There are six criteria, labeled A-F:

- Criterion A is exposure to one or more traumatic events: (A1) the person experienced, witnessed, or was confronted with an event or events that involved actual or threatened death or serious injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of self or others; and (A2) the person’s response involved intense fear, helplessness, or horror (which has since been dropped by the DSM-5 but has been included in the MHSS).

- Criterion B is one or more re-experiencing symptoms: recurrent and intrusive distressing recollections; recurrent distressing dreams of the event; reliving traumatic event (e.g., “flashbacks”); or intense psychological distressed and/or physiological reactivity when reminded of traumatic event.

- Criterion C is three or more avoidance symptoms: avoiding thoughts, feelings, or conversations about the trauma; avoiding reminders of the trauma; inability to recall important aspects of the trauma; diminished interest in significant activities; feeling detached/estranged from others; restricted range of affect; or sense of foreshortened future.

- Criterion D is two or more hyperarousal symptoms: difficulty falling or staying asleep; irritability or angry outbursts; difficulty concentrating; hypervigilance; or exaggerated startle response.

- Criterion E is a duration of more than 1 month of the disturbance (symptoms in criteria B, C, and D).

- Criterion F is clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning caused by the disturbance (symptoms in criteria B, C, and D).

The SCID used in the MHSS was adapted from the original SCID research version in order to make the time for the PTSD assessment to be the past year, rather than for the respondent’s lifetime or the past month. However, the screening questions for PTSD were about lifetime exposure to trauma and lifetime symptoms of re-experiencing or getting very upset by reminders of the traumatic event.

Subclinical PTSD was defined as a category for respondents who met criterion A (lifetime exposure and a reaction of intense fear, helplessness, or horror), criterion B (at least one re-experiencing symptom in the past year), and at least one criterion C symptom (avoidance in the past year). Thus, the “past year at least subclinical PTSD” category included respondents who also met the full criteria for PTSD.

Karg pointed out that the MHSS did not have adequate sample size to enable the researchers to look at three mutually exclusive categories: no subclinical or clinical PTSD, subclinical PTSD but not clinical PTSD, and clinical PTSD. This approach was consistent with how other studies have looked at subclinical PTSD (including clinical PTSD). Figure 2-1 shows a diagram of how traumatic event exposure and posttraumatic stress symptoms were assessed in the MHSS. Karg said that the interviewers administering the questions had graduate degrees in clinical psychology.

Because the report discussing the results from the study had not yet been released at the time of the workshop, Karg provided a general overview of the types of analyses that can be conducted on the basis of the clinical interview data. The data can provide estimates of the percentage of adults who had exposure to one or more traumatic events in their lifetime; past year subclinical PTSD (including clinical PTSD) among adults with lifetime trauma exposure; and past year clinical PTSD among adults with lifetime trauma exposure. The prevalence estimates of lifetime trauma exposure and past year subclinical and clinical PTSD can be analyzed by sociodemographic characteristics. Researchers can also examine mental health indicators, substance use, and chronic health conditions by lifetime trauma exposure and past year subclinical (including clinical PTSD).

Karg acknowledged that the MHSS had several limitations. One limitation was that the survey was conducted only in English, which meant that people who were not able to complete the survey in English had to be excluded. Another limitation was that the survey was primarily household based, and so it did not include some populations at higher risk for trauma exposure, such as people living in institutions, homeless people not living in shelters, and active-duty military personnel. In addition, due to the nature of the survey, the data could not be used to establish temporality or to suggest causal influences. Karg also added that the MHSS was based on the DSM-IV-TR, not the DSM-5.

SOURCE: Forman-Hoffman, V.L., Bose, J., Batts, K.R., Glasheen, C., Hirsch, E., Karg, R.S., Huang, L.N., and Hedden, S.L. (2016). CBHSQ Data Review: Correlates of Lifetime Exposure to One or More Potentially Traumatic Events and Subsequent Posttraumatic Stress Among Adults in the United States: Results from the Mental Health Surveillance Study, 2008-2012. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavior Health Statistics and Quality.

One difficulty of a study design that involves an initial interview and a follow-up assessment is that as the time between the interviews increases, so does the risk of false positives and false negatives on the follow-up assessment. Karg said that the goal was to complete most of the MHSS clinical interviews within 2 weeks following the NSDUH assessment, but completing them up to 4 weeks after the assessment was allowed.

An additional limitation discussed by Karg was the use of the SCID, and in particular the version that was used. Although the instrument is useful for estimating serious mental illness, it may not be ideal for estimating specific disorders or subthreshold diagnoses. Unlike the Composite International Diagnostic Interview, used in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) or the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule IV (AUDADIS-IV) used in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), the protocol used for the SCID in the MHSS called for stopping the administration of the disorder’s module once the criteria were no longer met. As she had noted, the definition of at least subclinical PTSD (respondents who met criteria A and B and at least one symptom of criterion C) also had limitations. In contrast, the NESARC requires meeting criterion A and one symptom each from criteria B, C, and D.

As part of her presentation, Karg also briefly discussed published estimates from other sources of nationally representative data. Wave 2 (2004-2005) of the NESARC—which, similarly to the MHSS, required PTSD criterion A1 (the person experienced, witnessed, or was confronted with an event or events that involved actual or threatened death or serious injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of self or others)—estimated that between 68 and 84 percent of adults had lifetime exposure to one or more traumatic events. The Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys, the National Survey of American Life, and the 2001-2003 NCS-R—all of which required both PTSD criteria A1 and A2 (the person’s response to the traumatic event involved intense fear, helplessness, or horror)—estimated that approximately 82-90 percent of adults had lifetime exposure to one or more traumatic events.

Karg noted that the results from the MHSS differ from the prevalence estimates obtained from other studies. The differences may be due to the use of screening questions: unlike other surveys, the MHSS included a set of screening questions in order to advance into the PTSD module. The MHSS respondents had to affirm lifetime PTSD criterion A1 and either of the lifetime criteria B questions asked to enter the SCID module that assessed past year PTSD.

Another potential explanation noted by Karg for the differences in the prevalence estimates may be related to the examples of traumatic

events used by the different surveys. The instruments used to assess traumatic event exposure differed with respect to the number and type of examples of traumatic events that were provided in the first question. For example, the MHSS gave examples of traumatic events in a single statement that read “. . . things like being in a life-threatening situation like a major disaster, very serious accident or fire; being physically assaulted or raped; seeing another person killed or dead, or badly hurt, or hearing about something horrible that has happened to someone you are close to.” In contrast, the NESARC provided a much more inclusive series of questions about specific traumatic events. Karg added that the new SCID for the DSM-5 also provides a much more exhaustive list of traumatic events. The differences in the estimates could also be due to variation in the assessment of PTSD. The NESARC and the NCS-R used fully structured interviews to assess and define traumatic events and posttraumatic stress symptoms. The MHSS used a semi-structured diagnostic interview that relied on clinical judgment in coding exposure to a traumatic event and the presence of posttraumatic stress symptoms. A final potential explanation provided by Karg for the differences relates to interviewer qualifications. The NESARC and NCS-R used lay interviewers who did not have input into the determination of whether or not an event was sufficiently traumatic to meet DSM-IV criteria. The MHSS used clinical interviewers who were trained to differentiate very stressful events from actual criterion A traumatic events, thereby reducing the possibility of false-positive reporting of symptoms.

In closing, Karg summarized the changes affecting the definition of PTSD as a result of the transition from the DSM-IV to the DSM-5. She said that in the DSM-5, criterion A2 (requiring fear, helplessness, or horror after traumatic event) was removed. The three clusters of DSM-IV symptoms are divided into four clusters in DSM-5: intrusion, avoidance, negative alterations in cognition and mood, and alterations in arousal and reactivity. DSM-IV criterion C (avoidance and numbing) was separated into two criteria: criterion C (avoidance) and criterion D (negative alterations in cognitions and mood). Three new symptoms were added in the DSM-5: persistent and distorted blame of self or others, persistent negative emotional states, and reckless or destructive behavior. In addition, several symptoms were revised to clarify expression.

Robert Ursano (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences) asked Karg to clarify how it was decided which traumatic event to ask about in cases in which respondents reported multiple traumatic events. Karg said that respondents were asked to specify which event had the most impact on their lives, but the interviewer was allowed to override a respondent’s answer on the basis of clinical judgment for the purposes of deciding which event to refer to in the follow-up questions. Ursano

commented that, traditionally, the follow-up questions are either asked for the event that the respondent specifies or for an event that is randomly selected from all traumatic events listed by the respondent. Karg said that the decision to allow the interviewer to substitute clinical judgment was made because in some cases a respondent may want to avoid talking about the event that was most upsetting to her or him. However, this type of change was very rarely made, if at all. Graham Kalton (Westat) asked how situations were handled in which the most traumatic event happened in the distant past and the respondent said that it no longer affected him or her. Karg responded that in these situations the respondent would not be administered the PTSD module.

Jonaki Bose (SAMHSA) said that it is very useful for SAMHSA to understand the tradeoffs associated with asking about only one event. One question is whether that approach is still better than not having any data at all, or are the biases introduced so large that this is not worthwhile doing. She urged the workshop participants to revisit this question throughout the day as part of the discussions about measures.

SOURCES OF NATIONAL DATA ON TRAUMA

Dean Kilpatrick (Medical University of South Carolina) delivered a presentation (prepared in collaboration with John Boyle, ICF International) on existing national survey data on the prevalence of exposure to potentially traumatic events and PTSD. He began by discussing several key definitional and methodological issues that he considers key to understanding epidemiological research on these topics. He noted that the word “trauma” is used in two ways: (1) a stimulus, that is, a stressor event capable of having negative effects on mental health and behavior or (2) a response of PTSD or related disorder that follows exposure to a stressor event. Similarly, when measures of trauma are discussed, they sometimes refer to measures of exposure to stressor events, sometimes to measures of responses following exposure to the stressor events, and sometimes to both measures of exposure and responses.

Kilpatrick pointed out that part of the reason for the lack of clarity is related to the importance of stressor events in the PTSD diagnosis. PTSD criterion A defines the types of stressor events capable of producing PTSD. If a stressor is not a criterion A event, it cannot, by definition, produce PTSD, so other PTSD criteria are not assessed. Many researchers call criterion A events traumatic events or potentially traumatic events. Kilpatrick commented that potentially traumatic event is a better term because not everyone exposed to a stressor event develops PTSD: in other words, events are only potentially traumatic. In addition, there are a variety of cultural, individual, biological, and other factors that deter-

mine whether an event becomes traumatic or not. Kilpatrick urged greater precision when discussing these concepts.

Revisions to the DSM have further contributed to the lack of clarity because they often involve changes to the definition of potentially traumatic events. Kilpatrick noted that the PTSD criterion A definitions of potentially traumatic events are different in the DSM-III, the DSM-III-R, the DSM-IV (and DSM-IV-TR), and the DSM-5. These differences also make it difficult to compare exposure or PTSD prevalence in studies that measure potentially traumatic events or PTSD symptoms using different editions of the DSM. One of the problems with the DSM-IV and DSM-IV-TR definition, he noted, is the inclusion of the A2 criterion that requires a response involving intense fear, helplessness, or horror. Including that criterion may have made sense theoretically, but staying true to that definition is very difficult in epidemiological studies.

Kilpatrick described several additional methodological issues associated with measuring the prevalence of potentially traumatic events and PTSD in population studies. One challenge is to collect data in the most cost-effective way, using methods that facilitate willingness to disclose information about exposure to all relevant potentially traumatic events, including those involving sensitive topics. A critical issue is whether the survey uses behaviorally specific questions to assess potentially traumatic events, especially for people with the highest probabilities of increased risk of PTSD (such as those involving sexual violence, other interpersonal violence, and military combat). If some of these potentially traumatic events are undetected by the data collection instrument, the survey is likely to underestimate PTSD prevalence. Another challenge highlighted by Kilpatrick is measuring PTSD using current DSM criteria in a way that is capable of producing accurate estimates of partial, subthreshold, and subclinical PTSD. If the goal is to capture these forms of PTSD, then adequately measuring a wide range of symptoms is important.

Kilpatrick noted that there are some challenges specific to measuring exposure to potentially traumatic events that are associated with sexual violence and other interpersonal violence. These types of violence are very prevalent and more difficult to measure than other events because of stereotypes and stigma surrounding them. The stereotypical image of rape is much narrower than the legal definition, and researchers find that when behaviorally specific terms are used that meet the definition of rape (e.g., something that happened while under the influence of drugs or alcohol, something done by a person that the respondent knows well, etc.), as many as half the respondents in a typical survey do not consider these types of events as rape. This disconnect (between the legal and a common stereotypical definition of rape) means that if the question simply asks whether the person has ever been raped, without referring to a

range of specific behaviors, many people will only think about reporting events that fit the stereotype. Terrence Keane (Boston University School of Medicine and Veterans Affairs National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder) noted that a similar problem occurs when asking military populations about combat, which is defined in many different ways by people who have been in war zones.

Kilpatrick said that well-designed studies, such as the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, indicate that 18 percent of adult women and 1-2 percent of adult men in the United States have been victims of rape. In terms of intimate partner violence, 36 percent of women and 29 percent of men have been victims of rape, physical violence, or stalking by an intimate partner.

Kilpatrick noted that there is a lot of research indicating that these types of potentially traumatic events cannot be measured with simple gatekeeping questions. Although it may be tempting to group several items together and ask a general question to save time and reduce the survey burden, respondents need to be provided with some context and be asked several screening questions in order to be able to consider what they are being asked and think about their responses.

Kilpatrick reminded participants of the four-step model of survey response,1 which was also discussed in a National Research Council report on estimating the incidence of rape and sexual assault.2 According to this model, respondents first need to comprehend the question and instructions. Second, they need to retrieve specific memories or information relevant to the question. Third, they need to make judgments about whether these memories or information match what is being asked in the question. Finally, respondents need to formulate a response based on a number of considerations, ranging from whether they think the answer is accurate to potential concerns about stigma or confidentiality.

Kilpatrick said that there are few studies that have produced national data on potentially traumatic events and PTSD. One notable exception is the NCS-R, which was conducted in the early 2000s, as a follow-up to the National Comorbidity Survey (which had been conducted in the early

___________________

1 Tourangeau, R. (1984). Cognitive sciences and survey methods. In Cognitive Aspects of Survey Methodology: Building a Bridge Between Disciplines. Committee on National Statistics, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education, National Research Council. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

2 National Research Council. (2014). Estimating the Incidence of Rape and Sexual Assault. Panel on Measuring Rape and Sexual Assault in Bureau of Justice Statistics Household Surveys, C. Kruttschnitt, W.D. Kalsbeek, and C.C. House, Editors. Committee on National Statistics, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

1990s). The NCS-R was a nationally representative probability sample of English-speaking adults age 18 and older, and it involved in-person interviews conducted by lay interviewers and fully structured instruments. The data collected included DSM-IV diagnoses, using the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview. The assessment of lifetime exposure to potentially traumatic events was very comprehensive, through a series of 26 questions about exposure to specific DSM-IV A1 criterion potentially traumatic events. These questions were followed by additional questions to find out which A1 events also met A2 criteria (the person having been terrified or frightened, helpless, shocked or horrified, or numb).

The NCS-R found that 79 percent of the respondents had been exposed to one or more potentially traumatic events on the basis of the DSM-III. Using the DSM-IV criteria, lifetime PTSD prevalence was 7 percent overall, 10 percent among women, and 4 percent among men. Past 12 months PTSD prevalence was approximately 4 percent overall, 5 percent among women, and 2 percent among men.

Kilpatrick also described the NESARC, conducted in 2004-2005, which was also a nationally representative probability survey of adults. The interviews were conducted in person, by lay interviewers, using the AUDADIS-IV, which is a fully structured interview instrument. The survey assessed lifetime exposure to potentially traumatic events and PTSD using DSM-IV criteria. The exposure was assessed with 27 questions enumerating specific potentially traumatic events. In the case of respondents who had more than one event, the event that was the worst was identified. The PTSD module measured what was called full and partial PTSD, asking about all PTSD symptoms with no skip-outs (i.e., all questions had to be answered). The survey also measured functional impairment.

The results on exposure to potentially traumatic events in the NESARC were very similar to the results from the NCS-R: the survey found that 80 percent of the respondents were exposed to at least one event. Lifetime prevalence of PTSD associated with the only or worst event was approximately 6 percent. Lifetime prevalence of partial PTSD, defined as not meeting full diagnostic criteria for PTSD but having at least one symptom in each of the B, C, and D criteria, was 7 percent. Kilpatrick said that he was not able to locate data on past year or current PTSD from the NESARC. However, NESARC data are available for lifetime mood, anxiety, substance use disorders, and suicide attempts: those data show that respondents with full PTSD, as well as those with partial PTSD, had elevated rates for those characteristics.

Kilpatrick also briefly discussed the NSDUH MHSS follow-on study, which had been described by Karg earlier. As noted, the assessment of exposure to potentially traumatic events was less comprehensive in the

MHSS than in other studies. Furthermore, in part because of the characteristics of the SCID, the PTSD symptom assessment module had many skip-outs, potentially excluding many respondents who may have had undetected events. Kilpatrick said that an approach such as the one used by the MHSS unavoidably leads to lower estimates of potentially traumatic events and PTSD than those obtained by other studies. Attempting to assess partial PTSD or subclinical PTSD using this method would be nearly impossible because respondents are not asked about the full range of symptoms. He added that the use of clinically trained interviewers in epidemiological studies of this type is also not ideal, because error variance could increase if the interviewers are substituting clinical judgment for respondents’ reports and introducing differences in the way questions are asked or which questions are asked.

Commenting on the implications of the transition from the DSM-IV to the DSM-5, Kilpatrick said that due to the changes, data on exposure to potentially traumatic events and of PTSD that were based on the DSM-IV cannot be used to determine prevalence rates in accordance with the DSM-5. He summarized the key DSM-5 changes to criterion A events as follows:

- Potentially traumatic events no longer have to produce “fear, helplessness, or horror.”

- The types of sexual violence events defined as potentially traumatic events were expanded.

- Learning about the unexpected death of a close family member or friend is no longer a potentially traumatic event unless the death was violent or accidental.

- A new category of potentially traumatic events was added that involves work-related repeated or extreme indirect exposure to aversive details of potentially traumatic events experienced by others.

- There is an explicit recognition that exposure to multiple potentially traumatic events is common and that PTSD can occur in response to more than one event.

In addition to changes in the criterion A events, Kilpatrick highlighted the following additional revisions in the DSM-5 (see the list of DSM-IV criteria above):

- Three new symptoms (D3, D4, and E2) were added, and four others (D1, D2, D7, and E1) were modified.

- Symptom-based criteria were restructured from three in DSM-IV to four in DSM-5.

- Nonspecific PTSD symptoms are now required to develop or worsen after exposure to a potentially traumatic event or events.

- There is an acknowledgment that PTSD symptoms can incorporate responses to more than one potentially traumatic event.

In conjunction with the DSM-5 PTSD work group, Kilpatrick was involved in the development of a web-based assessment instrument designed to evaluate the impact of the proposed diagnostic changes on estimates of PTSD prevalence, and he described some of the findings from that project. The instrument was used in two surveys: the National Stressful Events Survey (NSES) and the Veterans Web Survey (VWS). The NSES sample (N = 2,953) was recruited from a national online panel of U.S. adults,3 while the VWS sample (N = 345) included veterans who had previously agreed to be contacted about research studies at the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs National Center for PTSD in Boston.4

Kilpatrick discussed one of the two studies, the NSES. He said that the survey was self-administered but designed to mimic a highly structured clinical interview with follow-up questions. The instrument measured all DSM-5 PTSD criterion A events, DSM-IV A1 events scheduled for elimination, and DSM-IV criterion A2 events. In addition, all 20 DSM-5 PTSD symptoms were measured, and the instrument included follow-up questions to determine which traumatic event or events were involved with each symptom, how recently the symptom had occurred, and how disturbing the symptom was during the past month. For new and modified symptoms, follow-up questions were asked to determine which elements of the symptom were being experienced by the respondent. The survey also measured functional impairment. Kilpatrick said that the data collection demonstrated the feasibility of collecting information using DSM-5 criteria.

The study found a slightly higher percentage of exposure using the DSM-5 criterion A events than had been found in the other studies discussed. Approximately 88 percent of respondents reported at least one such event. For events that were excluded from the DSM-IV, there was an approximate 4 percentage point drop when using the DSM-V criteria. Kilpatrick said that the percentage of people who experienced only one

___________________

3 For details, see Kilpatrick, D.G., Resnick, H.S., Milanak, M.E., Miller, M.W., Keyes, K.M., and Friedman, M.J. (2013). National estimates of exposure to traumatic events and PTSD prevalence using DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26(October), 537-547.

4 For details, see Miller, M.W., Wolf, E.J., Kilpatrick, D., Resnick, H., Marx, B.P., Holowka, D.W., Keane, T.M., Rosen, R.C., and Friedman, M.J. (2013). The prevalence and latent structure of proposed DSM-5 posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in U.S. national and veteran samples. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 5(6), 501-512.

potentially traumatic event was very small (approximately 15% of all respondents), and this low rate underscores the importance of developing an approach that can take it into account.

Kilpatrick and his colleagues defined composite event PTSD “caseness” as cases that meet criteria B, C, D, and E symptoms with a combination of criterion A stressor events (must have at least one B, one C, two D, and two E symptoms to some combination of DSM-5 criterion A events) and also have functional impairment. They defined the requirements for same event PTSD “caseness” as at least one B, one C, two D, and two E symptoms to the same DSM-5 criterion A stressor event, combined with functional impairment.

Parallel definitions were used for the DSM-IV criteria. One question for the researchers was whether the transition to the DSM-5 would lead to substantially increased estimates of prevalence. Kilpatrick said that in terms of the composite event and same event PTSD rates, the differences between the DSM-IV and DSM-5 rates were small, and to the extent differences existed, the DSM-5 rates were in fact slightly lower than the DSM-IV rates.5

Kilpatrick said that the data from the NSES show that it is feasible to develop a self-administered, structured survey instrument and collect cost-effective data that measure all potentially traumatic events following the DSM-5 criteria using behaviorally specific questions, all DSM-5 PTSD symptoms, and PTSD-related distress, along with functional impairment. This assessment strategy was able to determine which PTSD symptom occurred in response to multiple potentially traumatic events, which provides an approach that can be implemented in large-scale surveys to address the methodological challenges associated with measuring exposure to more than one event and with the fact that risk of PTSD is related to the number of potentially traumatic events experienced.

In closing, Kilpatrick emphasized that he believes that any epidemiological study attempting to measure PTSD needs to include a thorough, detailed assessment of exposure to potentially traumatic events, using behaviorally specific terms. Although the temptation to keep the number of questions to a minimum is understandable, studies that attempt to cut corners could be seriously flawed. On the other hand, if potentially traumatic events are adequately measured, it is relatively easy to determine based on survey data how exposure increases PTSD risk and the risk of other mental disorders. To obtain estimates of partial, subthreshold and subclinical PTSD, it is necessary to measure all DSM-5 PTSD symptoms. Although skip-outs are often used, Kilpatrick does not consider this to be a methodologically sound approach. He also noted that it is important

___________________

5 See reference in fn. 4, above.

to begin moving away from the notion that PTSD should be assessed in relation to only one event. When earlier versions of the DSM were published, the assumption was that exposure to multiple events was rare, but research has shown that this is not the case.

Kilpatrick also addressed the role of clinically trained interviewers in collecting PTSD data in large-scale surveys. Although clinician-administered semi-structured interviews are generally considered the “gold standard,” these interviews are not only expensive, but they can also be less reliable than standardized interviews conducted by lay interviewers because, as noted earlier, different clinicians using different follow-up probes and substituting their own judgments for what the respondent said can lead to greater error variance. He added that conducting the interviews in person may also not be necessary. Instead, multimode data collection approaches could be considered, with at least some of the interviews conducted through modes other than face to face, and the cost savings could be used to increase sample size.

Keane said that clinician judgment used to be very important in the study of PTSD, but over the course of the past few decades, researchers have noted remarkable convergence of data obtained from surveys and from clinical studies. The success of the NSES survey points to a cost-effective mechanism for collecting these types of data and also provides valuable guidance for public policy in this area.

Terry Schell (RAND) commented that the main limitation of the NSES approach is the web-based sample, which is inexpensive but not truly nationally representative. However, if a nationally representative sample already exists, such as the NSDUH, then a web-based approach can be used for a follow-on survey, and it would have several advantages over a follow-on survey conducted by telephone. In addition to reduced costs, a self-administered questionnaire delivered by the web also represents a better substitute for the Audio Computer-Assisted Self-Interview used in the NSDUH. He noted that data show that trauma exposure, in particular, tends to be underreported in telephone surveys.

Hortensia Amaro (University of Southern California) asked whether a web-based assessment could introduce any biases due to lower rates of internet access or lower proficiency with using the internet among some population groups. Kilpatrick responded that survey methodologists are studying these questions and that it seems clear that multimode approaches are needed. Each mode has some advantages and disadvantages.

Kalton wondered whether it would be possible to begin with questions about PTSD, if that is the primary goal of the data collection, and then ask follow-up questions to try to determine the causes of the PTSD. This approach could reduce the problems associated with measuring

exposure to multiple events, many of which are not relevant. Kilpatrick said that PTSD is different from other mental health issues, such as depression, because PTSD is a response to an event. Thus, it is important to get people to think about whether they have any problems that are in response to things that have happened to them.

Evelyn Bromet (Stony Brook University) commented that studies on exposure to potentially traumatic events, PTSD, and risk factors have been consistent in their findings over the past several decades and that more targeted research is needed to produce information that could be used for prevention, instead of focusing on prevalence rates. Keane responded that there have been changes in traumatic experiences and their impact on people’s lives, noting in particular a change since 9/11. Consequently, he said, it is important to continue to keep track of prevalence rates if it can be done at a modest cost. Updated prevalence rates also help keep the issue in front of policy makers. Kilpatrick added that prevalence rates for serious mental disorders drive funding allocation for states, and if PTSD is not included, then people with PTSD could be underserved in term of resource allocation.