4

Recruitment and Retention Issues: Patient, Provider, Institutional, and System Barriers

Factors spread throughout the clinical trials ecosystem affect minority recruitment and retention. Many of these factors directly involve the patients who ultimately agree or decline to participate in a trial. But many factors also involve health care providers and systems, communities, businesses, and governments.

Three speakers described some of the ways that components of the clinical trials ecosystem can work together to influence these factors. The community is often the locus of these efforts, since it can look both out to broader societal institutions and in toward families and individuals.

THE INTEGRITY OF RESEARCH AND CLINICAL TRIALS

Cancer clinical trials are meant to improve the health and well-being of future patients, said Connie Ulrich, associate professor of bioethics and nursing at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing. Such trials potentially reduce disparities and promote the generalizability of information. They test new treatments and improve models of care, and they help move science from the bench to bedside.

But low recruitment and retention rates in clinical trials are problematic, she continued. Only 3 percent to 5 percent of all eligible adults participate in clinical trials, which reduces the ability to develop effective and efficacious treatments for all relevant population groups.

One reason more people do not participate in clinical trials involves the integrity of research, Ulrich explained. Media stories about misconduct in research can create fear among members of the public, and examples

of past abuses of human participants can compound those fears. Patients fear that they will be used as human guinea pigs, Ulrich said, adding that “There is a perception of untrustworthy science and scientists, which I think hurts the integrity of science and ultimately the public trust in the research enterprise.”

Ulrich cited several representative quotations from patients: “Before I decided ‘yes’ for the clinical trial, both my husband and I were very confused with the events leading up to my trial study. I believe more information in layman’s terms [needs to] be explained to the patient.” Another patient stated that “I think the big problem is word of mouth. Too many people are told by too many other people who are not knowledgeable and who have a negative attitude or who have developed a mindset maybe through a relative who died of cancer or some other disease. . . . I think people are just turned off by what they hear.”

Information is generally available for patients about clinical trials, Ulrich observed, but there can be a disconnection between what people understand and the knowledge they need to be able to give informed consent and participate.

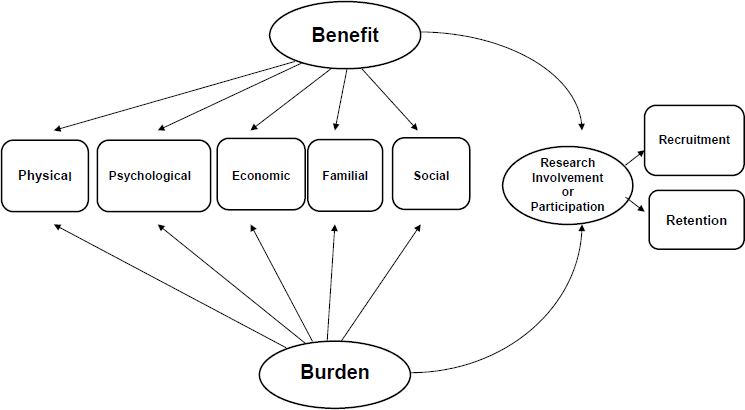

Ulrich and her colleagues have been studying the benefits and burdens of research participation in cancer clinical trials. They have developed a model of the many factors that shape the benefits and burdens of participation and thus recruitment and retention (see Figure 4-1).

SOURCE: Ulrich et al., 2012.

The variety and salience of these factors make decisions extremely challenging. Ulrich quoted one patient as saying, “Fear of the unknown has got to come into a lot of people’s heads. Why would I put myself through something that I do not know what the effects are going to be, if I’m even going through that added stress? Why bother, why do that to me, when I’m already dealing with enough on my plate?” People can be fearful of the experimental treatment itself and what side effects it might have. They may be concerned that they will receive the placebo rather than the treatment. They may worry about whether they will continue to receive good care after the trial ends.

Ulrich and her colleagues compiled a list of issues that increase the burden of research participation, in order of increasing frequency among patients:

- It is costing me money out of pocket.

- It might not benefit me.

- There are unknown side effects that are potentially life threatening.

- I have had to rearrange my life to participate.

- I have experienced bothersome side effects.

- It makes me worry about other family members.

- It has made me recognize the seriousness of my disease.

- I would be disappointed if I received a placebo.

Other burdensome issues were the uncertainty of whether a treatment is helping or hurting, the failure of insurance to cover all expenses, the need to rely on others, managing the disease, fatigue, quality-of-life issues, balancing family needs, and an overwhelming amount of information to understand. The higher the burden of concerns, the more people thought about dropping out of a trial.

Ulrich and her colleagues also developed a list of issues about the benefits of research participation, again in order of increasing frequency among patients:

- It might help my children or other family members in the future.

- I am able to extend my life.

- I am hoping for a cure.

- It is a way for me to actively treat my disease.

- It gives me a sense of hope about my disease.

- I am treated like a person and not a number.

- I am providing a valuable contribution to society.

- I might help future patients with my disease (although it might not help me).

Other benefits listed by patients included trusting the researchers, access to drugs and other medicines or tests that are not available otherwise, feeling more informed, having control over a disease, lessening stress, helping to pay costs of drugs and other medicines, insurance coverage, and reducing risks in the future. The higher the perception of benefits among patients, the less likely they were to think about dropping out of a trial.

INFORMED CONSENT AND OTHER FACTORS

Ulrich has also studied the issue of informed consent. When clinical trial participants were asked whether they assessed the risks and benefits directly associated with participating in the trial, 52 percent said no and 48 percent said yes. “My colleagues and I have been talking about whether this is really informed consent as we think about informed consent,” she said. Individuals who did not assess the risk delegated their autonomy to their physician to make the decision. They tended to be older, more trusting, have less education, perceive that they had limited treatment options, rated their spirituality as important, indicated that the trials helped to pay the cost of care, were retired or not employed, and reported being unsure or that they do not feel informed when they enrolled or were informed about study changes (Ulrich et al., 2015).

As a pediatric nurse by training, Ulrich also was interested in the role of nurses associated with clinical trials to help people better understand the issues they face. When patients were asked about the importance of communicating with the research nurse, 85 percent said it was very important to them. Nurse communication also was significantly associated with patients remaining in the trial. “Nurses should be part of [interdisciplinary] teams,” said Ulrich. “They clearly are important and can provide information to patients.”

Relational communication also was significantly associated with patients remaining in a trial. Such communication involves being compassionate and honest toward a patient, providing a friendly and relaxing environment, speaking in a way that the patient understands, encouraging patients to ask questions, reviewing study information, and helping them feel good about a particular situation. Doctor communication and nurse communication were both positively correlated with the patient being informed, which “speaks to the importance of interdisciplinarity and the role of teams with research,” said Ulrich.

Finally, Ulrich defined interdisciplinary integrity as a commitment on the part of the clinical and research teams to provide honest and clear information about the benefits and burdens of clinical trials in an atmosphere that respects the rights of human participants as active partners in decision making. Such integrity is essential to research participation, she said.

In closing, Ulrich said that more work is needed on the benefits and burdens of research participation. For example, she is involved in a study on the weight that patient participants give to informed consent compared to other factors in recruitment and retention. More data are also needed on the attitudes, beliefs, and practices of health care providers and the link between clinicians and researchers, she said. “We need to bridge the gap between the researcher and primary care, especially those primary care providers whose patients are seen within our communities,” Ulrich concluded.

PATIENT PERSPECTIVES ON CLINICAL TRIALS

As was pointed out by all three members of the panel, the term clinical trial generates many questions in the minds of patients. In his remarks, Moon Chen, professor in the Division of Hematology and Oncology, Department of Internal Medicine, at the University of California, Davis, School of Medicine, noted that the word trial has multiple meanings in English, some of which have negative connotations. When a clinical trial is described as an experiment, people can be fearful of having experiments conducted on them. “What would be a better translation or English terminology for clinical trials?” he asked, “because that is the major obstacle in moving forward.” Additionally, trial in lay terms could also refer to legal proceedings, and thus, that reference could also invoke negative reactions.

Every major population group is going to experience an increased number of cases of invasive cancers in the United States in coming years, Chen noted. Yet of approximately 10,000 clinical trials funded by NCI and listed on ClinicalTrials.gov, fewer than 150 were substantively focused on racial or ethnic minorities, including 83 on African Americans, 32 on Latinos, 5 on Asian Americans, 8 on Native Americans and Alaska Natives, and 1 on Pacific Islanders (Chen et al., 2014). Despite the 1993 NIH Reauthorization Act, investigators are prioritizing disease over adequate racial or ethnic representation, said Chen.

Stakeholders have many different perspectives on clinical trials, Chen observed, including patients, researchers, health care providers, IRBs, and families. But research shows that providers are the most influential factor in patient enrollment in clinical trials. Chen recalled being asked to recruit a patient into a trial because he was the only one available who spoke Cantonese. “I’m so glad that I was called to meet with this patient to recruit her to clinical trials because she would not have volunteered,” he added.

Chen’s research has demonstrated that the factor mentioned most often as a barrier to participation in clinical trials is distrust and discomfort with uncertainty in a trial. “We are going to have to deal with how to overcome that through authenticity and willingness to invest time,” he said.

People have many other questions about clinical trials: How am I going to get there? How do I handle my family responsibilities? Do I ask for time off from work? Who is going to take care of my children? Some of the relevant factors are demographic, involving gender, age, education, insurance coverage, and income. Others are social, including considerations of altruism, stigma, and communicability. Some factors are cultural, including values, beliefs, historical experiences, and fear and mistrust.

Echoing other presenters, Chen said that the foundation of participation is trust. The question is how to engender and earn trust. Chen said that trust is built on a record of believability, credibility, fulfillment of prior commitments, and shared interests. He also said, in response to a question, that respect is a critical factor in the relationship between a patient and a health care provider. For example, many Asian patients view their physicians as respected figures, which means that their eyes look down in the presence of a physician. This creates even greater responsibility on the part of the provider to honor that respect.

As with restaurants, word of mouth is a powerful way to build trust, and Chen urged that a similar approach be taken with clinical trials. This approach typically takes time to understand community concerns, build relationships, and conduct outreach and education. It also requires involving the community in every step of the process. And it requires transparency in the form of culturally appropriate and ethnically specific outreach and education, continuous community input and feedback, and community ownership.

As an example, Chen cited the Thousand Asian American Study, which is “all based on trust because it was based on a track record of earned respect.” Educational sessions are available using a brochure and video. Patients work through a computerized menu in which they can chose from five languages or receive spoken information. Patients receive follow-up on possible enrollment in a trial. The experience has shown that minorities are willing to participate in health research, said Chen (Dang et al., 2014).

One dramatic way to promote greater participation, said Chen, would be for journals not to accept research articles unless the research has meaningful representation and analysis of data by racial or ethnic groups, with several of the higher-impact journals trending in this direction. This suggestion reveals the extent to which journal editors and reviewers have an opportunity to affect minority participation in clinical trials.

Another possibility would be to convene the leaders of journals to discuss requiring or recommending that any time minority groups participate in a trial, their participation yields meaningful data. “This is where the NIH and FDA can really exercise their influence, because we will follow,” he said. “If they change the format for the instruction to authors, we will make our changes.”

Chen said that the authors and reviewers of scientific papers have an opportunity to practice what they preach, adding that “when we write up our results, we want to make sure that the minority populations or the populations that we deal with are adequately represented and the data is analyzed sufficiently so that it is meaningful to advance the science.”

Chen also made the point, in response to a question, that “All adults are underrepresented in clinical trials.” Pediatricians have been better about enlisting children into clinical trials, which raises the question of whether lessons can be learned from their approaches to increase the numbers and diversity of adults in trials.

ENGAGING COMMUNITIES IN HIV RESEARCH

Community engagement can improve the feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of research, said Jonathan Ellen, president at Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital. These goals are all more complicated when working with vulnerable populations at risk of HIV infection.

Youth aged 13 to 24 accounted for an estimated 26 percent of all new HIV infections in the United States in 2010. Most new HIV infections among youth occur among gay and bisexual males. Among 15- to 19-year-olds, the highest percentages of new infections in minority youth are among African Americans (56 percent), Latinos (21 percent), and Pacific Islanders (15 percent). Recognizing the vulnerability of these populations, leaders at NIH stepped up, said Ellen, and issued a call to action to build a community infrastructure of prevention and partnerships.

Communities are not always accepting of this attention, Ellen observed. As was pointed out by Ulrich, some communities mistrust researchers because of a history of experimentation that has involved those communities. For example, Ellen worked for many years on syphilis elimination in Baltimore, Maryland, which required continually addressing concerns about the Tuskegee syphilis experiments. Clinical trials also have the potential to stigmatize communities by identifying and associating them with particular problems.

With HIV infections, a critical step in the “cascade of care,” said Ellen, is diagnosis. Once an infection has been identified, patients can be linked with care, retained in care, and treated. However, only about 40 percent of infected adolescents are being diagnosed, compared with 82 percent of adults, Ellen noted. Furthermore, only about 6 percent of HIV-infected youth are having their infections suppressed. “That is a problem both from a public health standpoint and from an individual standpoint in terms of the progression of infection,” he said.

To address the problem, NIH supported a community consultation in 2001 to talk with stakeholders about the potential involvement of com-

munities in adolescent HIV trials. This consultation uncovered a clear interest among communities in having their youth participate in trials. But the communities also expressed a desire to have the trials be part of larger prevention activities that involve the entire communities. The stakeholders also asked to be educated about vaccines, that the impact of the trials on the community be measured, and that community participation precedes the vaccine trials.

The Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions (ATN) has engaged in three important strategies to carry out these requests. The Connect to Protect project sought to determine whether community mobilization can lead to structural changes, in the form of new or modified policies, practices, and procedures, and whether these changes can lead to decreased risk for HIV transmission. The structural changes had to be logically linked to HIV acquisition and transmission and sustained over time, so that the changes would persist even when key actors were no longer involved. The changes also had to have a direct or indirect effect on individuals so that communities and the members of those communities would be safer.

The critical component of the program, said Ellen, was community mobilization, which he defined as collaborative problem solving that leads to fewer health or other social problems. Sustained efforts over time were essential to the effectiveness of the mobilization, and leadership, ongoing feedback, and continued growth in capacity were key elements of the sustained effort.

Ellen listed some of the structural changes made as part of this program:

- The Louisiana Juvenile Justice System will implement HIV/sexually transmitted disease (STD) screening of youth upon intake into New Orleans juvenile justice facilities.

- The Shelby County Health Department (Memphis) will change its policy to allow alternate forms of identification from individuals seeking HIV test results.

- All Montefiore Community Health Centers (Bronx) will modify policies to offer routine HIV testing to patients over 13 years old.

- The Washington, DC, Department of Health will require all grantees that are HIV testing/treatment sites to adhere to youth competency protocol.

- The Florida Department of Health will register Our Kids of MiamiDade and Monroe as HIV testing sites for youth in foster care.

- The Hillsborough County Health and Human Services Ryan White Administration will amend guidelines to exempt minors with HIV from providing income eligibility documentation.

- The Detroit Receiving Hospital emergency room will have a new policy to refer youth into care when they test preliminary positive.

- The New Orleans Regional Transit Authority will provide free bus tokens to HIV-positive youth referred for medical care.

- The Fenway Medical Division (Boston) will modify its existing appointment policy for HIV-positive youth to ensure that all youth receive a scheduled follow-up appointment at the end of all medical visits.

- Denver’s school-based health centers will adopt a long-term care policy for students identified as HIV-positive.

Since the program started in 2002, Ellen reported, “There has been an amazing amount of transformation that has gone on in these communities.”

The second project was known as the ATN Community Education Plan. People have many questions about clinical trials, starting with what a trial is. Many do not know what a placebo is, the distinction between treatment trials and prevention trials, or the meaning of clinical research. Informed consent may not be the most important factor for an individual to be enrolled in a trial, Ellen said. Such factors as the characteristics of the provider, trust, respect, or even logistics may be more important. Furthermore, “a whole host of cultural and social factors” come into play in a clinical trial beyond the pharmacokinetic properties of a drug in the body, he explained. For example, adherence to a treatment can affect the outcome a clinical trial, and adherence can vary by population group.

In each community, the protocol chair and team made a determination of the need for an education plan. This education took place in a wide range of places—churches, schools, Boys & Girls Clubs—and reached out to a wide range of populations, including youth, adults, and parents. The content of the education ranged from basic information to quite sophisticated concepts. For example, the definition of clinical research presented in the educational modules was:

- Research is an investigation to find an answer to a problem.

- Research tries to find better ways to prevent, diagnose, treat, and understand illness.

- Clinical trials can test new medications and vaccines.

- Clinical trials depend on the people who volunteer to participate in the research.

The educational program also described major types of clinical research (see Table 4-1). The program also described why clinical research is important for everyone:

TABLE 4-1 Types of Clinical Trials

| Type of Trial | Goal |

|---|---|

| Treatment | To test new medications or procedures that could help to treat an illness |

| Prevention | To look for better ways to prevent an illness in people who have never had the illness. Better ways to prevent an illness may include medicines, vaccines, and/or lifestyle changes |

| Diagnosis | To find better tests or procedures for identifying a particular illness or condition |

| Screening | To test the best way to detect certain illnesses or health conditions |

| Quality of Life | To explore ways to improve the comfort and quality of life of people with a long-term illness |

SOURCE: Ellen presentation, April 9, 2015.

- Illnesses do not affect everyone in the same way.

- Medicine does not always work the same in everyone.

- Clinical research helps us understand what these differences are and why they happen.

The third project was known as the Community Impact Monitoring Plan, which had the goal of combining ongoing assessments from the community, particularly from those members most affected by the research, with assessments from the research group and established community advisors to provide a comprehensive view of the effect the research is having on the community. Phase I of the plan determined the need and, if required, identified community-related consequences. Phase II developed a plan for information collection necessary to monitor the effect on the community. Phase III consisted of annual reporting to the Community Impact Monitoring Plan Oversight and Ethics Advisory Committees. In essence, said Ellen, the goal of the plan was to apply the ethical concepts usually applied to individuals, in such areas as privacy and autonomy, to communities.

Ellen concluded by briefly mentioning two important trials that have gone on within the ATN. The first was working with youth less than 18 years old on preexposure prophylaxis, which required working with the IRB to gain consent from people younger than 18 without their parents’ consent. The second involved surveys with youth ages 13 and up, which required the awareness and participation of community leaders. Both required the infrastructure established by the ATN, he said, to be successful.

As Ellen pointed out in response to a question, building a coalition of stakeholders and keeping them engaged are critical in efforts to work with communities. Paying people, however, to participate can create problems. Instead, providing technical assistance and other forms of support to com-

munity coalitions can catalyze their work and keep them active. “You can get a broad coalition maintaining itself in a community that then can work, when the time comes, for these trials,” he added.

He also pointed out, in response to another question, that partnerships mean giving up some authority and power. “Otherwise, you are not really entering into a partnership.” A true partnership is built on trust, and building this trust requires time, he said. “It is not something you can do on the cheap, and it is not something you can do afterwards with the analysis. That kind of investment . . . has to happen intentionally, and it is going to cost some resources,” Ellen concluded.

IMMIGRANT POPULATIONS

One of the topics discussed during the question-and-answer session involved the particular challenges of enrolling immigrant populations in clinical trials. Asian populations are diverse in terms of language, Chen said, which requires working with translators for those languages. These translators should understand and have “a paragraph-long explanation of what a clinical trial is,” he added, since two words are not enough to explain the concept.

Ulrich said that few data are available on how immigrant populations view clinical trials and the accompanying benefits and burdens. Furthermore, terms like placebo, randomization, or equipoise mean little to most people.

Ellen responded that immigrant populations are very different, whether Russian, Ethiopian, or Chinese immigrants. He also pointed out that language to some extent acts as a proxy for acculturation, in that populations that have mastered English tend to be more acculturated. With populations still speaking largely in some other language, cultural issues can increase the difficulty of explaining what a clinical trial is and what a particular trial entails.

This page intentionally left blank.