7

Estimating the Fiscal Impacts of Immigration—Conceptual Issues

7.1 INTRODUCTION

In formulating immigration policy, information about the impact of immigration on public finances is crucial. Along with the impact on wages and employment (see Chapters 4 and 5), the per capita impact on taxes and program expenditures is the other factor determining the extent to which immigrants are or will be net economic contributors to the nation. The New Americans (National Research Council, 1997, p. 225) identifies two other reasons why estimates of current and long-run fiscal impacts are important to policy: First (as discussed in Section 7.5 below), immigration may create taxpayer inequities across states and local areas; specifically, regions that receive disproportionate shares of immigrants may incur higher short-run fiscal burdens if the new arrivals initially contribute less in revenues than they receive in public services. Second, projections of the consumption of public services and payment of taxes over time are essential in order to predict “the full consequences of admitting additional immigrants into the United States.” This chapter discusses the conceptual issues that arise when estimating the fiscal impacts of immigration, recognizing that it is a complex calculation dependent to a significant degree on what the questions of interest are, how they are framed, and what assumptions are built into the accounting exercise. In so doing, the discussion here provides a foundation for the empirical analyses conducted by the panel and reported on in Chapters 8 and 9.

Understanding of the fiscal consequences of immigration has often been clouded because much of the research is conducted by policy-focused

groups that tailor the assumptions to support one position over another. As described by Vargas-Silva (2013, p. 1), “Most of these organizations have a set agenda in favour or against increased immigration. Unsurprisingly, those organizations with a favourable view of immigration tend to find that immigrants make a positive contribution to public finances, while those campaigning for reduced immigration tend to find the contrary.” The partisan nature of the policy debate notwithstanding, careful estimates based on defensible methodologies are possible. The New Americans, a pioneering effort in this respect, included a detailed discussion of methodological considerations that is still highly relevant (National Research Council, 1997). That volume, along with more recent studies, such as Auerbach and Oreopoulos (1999), Dustmann and Frattini (2014), Preston (2013), Rowthorn (2008), Storesletten (2003), and Vargas-Silva (2013), significantly advanced the conceptual framework for thinking about fiscal impacts, making the task much easier now than it was at the time that The New Americans was written.1

The first-order net fiscal impact of immigration is the difference between the various tax contributions immigrants make to public finances and the government expenditures on public benefits and services they receive. However, a comprehensive accounting of fiscal impacts is more complicated. Beyond the taxes they pay and the programs they use themselves, the flow of foreign-born also affects the fiscal equation for many natives as well, at least indirectly through labor and capital markets. Because new additions to the workforce may increase or decrease the wages or employment probabilities of the resident population, the impact on income tax revenues from immigrant contributions may be only part of the picture. Revenues generated from natives who have benefited from economic growth and job creation attributable to immigrant innovators or entrepreneurs would also have to be included in a comprehensive evaluation, as would indirect impacts on property, sales, and other taxes and on per capita costs of the provision of public goods.

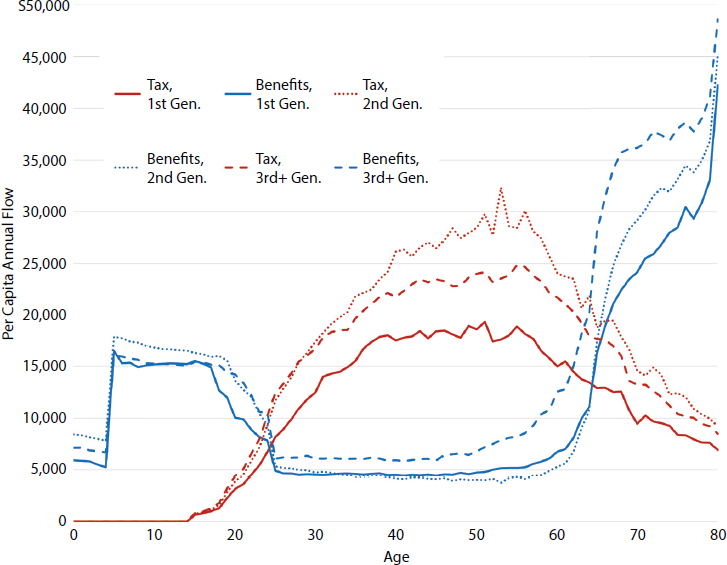

Additionally, the full fiscal impact attributable to a given immigrant or immigration episode is only realized over many years. As shown in Figure 7-1, albeit with cross-sectional data, the distribution of individuals along the life cycle displays systematically different tax contribution and program expenditure combinations. For example, the child of an immigrant—as with the child of a native-born person—is likely to absorb resources early in life (most notably due to the costs of public education) and therefore is likely

___________________

1 Referencing this literature affords the opportunity to shorten the methodological discussion here; however, when reporting the panel’s own fiscal estimates, in Chapters 8 and 9, we document in detail the expenditure and revenue categories used in the estimation, along with the underlying methods, assumptions, and modeling choices.

NOTE: All public spending is included in benefits except pure public goods (defense, interest on the debt, subsidies). Data are per capita age schedules based on Current Population Survey data, smoothed and adjusted to National Product and Income Accounts annual totals.

SOURCE: Panel analysis of Current Population Survey data.

to exert a net negative impact on public finances initially. However, later in the life cycle, working and tax-paying adults typically become net contributors to public finances. A full accounting of the fiscal effects of immigration therefore requires information about “the additional or lower taxes paid by native-born households as a consequence of the difference between tax revenues paid and government benefits received by immigrant households over both the short and the long term” (Smith, 2014a, p. 2). Reliable estimates of taxpayer impacts over time are important elements of a thorough economic analysis of the costs and benefits of immigration (Smith, 2014a).

The impact of immigrants on government finances is sensitive to their characteristics, their role in labor and other markets, and the rules regulating accessibility and use of government-financed programs. It is often important to distinguish country of origin and legal status of immigrants, as

groups differentiated by these characteristics experience different outcomes in the labor market and different take-up rates for government services. Inclusion of detailed individual-level characteristics (age, education, etc.) may adequately address these observed fiscal costs and benefit differences across origin countries.2 Even so, due to this heterogeneity, it is impossible to reach generalizable conclusions about the fiscal impact of immigration because each country’s or state’s case is driven by a rich set of contextual factors. Impacts vary over time as laws and economic conditions change (e.g., pre- and post-financial crisis) and by place of destination (e.g., by country, region, and state—each of which has its own policies and population skill and age compositions). It is also important to note that, during periods when fiscal balances for immigrants become increasingly negative, such as during major recessions, they likewise become increasingly negative for natives.

The potential of immigration to alter a country’s or state’s fiscal path is greatest when the sociodemographic characteristics of arrivals differ distinctly from those of the overall population—and particularly when these characteristics are linked to employment probability and earnings. In the United States, first generation immigrants have historically exhibited lower skills and education and, in turn, income relative to the native-born. Analyses of New Jersey and California for The New Americans (National Research Council, 1997, pp. 292-293) concluded that the estimated negative fiscal impacts during the periods 1989-1990 and 1994-1995, respectively, were driven by three factors: (1) immigrant-headed households had more children than native households on average, and so consumed more educational services on a per capita basis; (2) immigrant-headed households were poorer than native households on average, thus making them eligible to receive more state and locally funded income transfers; and (3) due to their lower average incomes, immigrant-headed households paid lower state and local taxes. Recently, though, the share of foreign-born workers in high-skilled occupations has been increasing, partly as a result of the H-1B visa programs initiated in the 1990s. But even after education and other characteristics are accounted for, immigrants’ labor market outcomes are often less positive than their native-born counterparts. One explanation is that the skills gap may be exacerbated by underemployment due to downgrading of education and other qualifications, at least for a period after arrival. An interesting question is whether immigration may have some fiscal impact, even if it does not alter the composition of the resident population—that is, if immigrants had the same characteristics as

___________________

2 In a reassessment of state-level analyses from The New Americans, Garvey et al. (2002) found that divergent fiscal impacts, originally attributed to country-of-origin effects, could be explained by different socioeconomic characteristics.

the native-born population. The answer depends in part on the extent to which immigrants assimilate into or out of the welfare state and into or out of the labor market.

Age at arrival is an important determining fiscal factor as well, because of its relation to the three factors identified above. Immigrants arriving while of working age—who pay taxes almost immediately and for whom per capital social expenditures are the lowest—are, on average, net positive contributors. In The New Americans’ fiscal estimates for the 1990s, a 21-year-old with a high school diploma was found to have a net present value of $126,000. This value gradually declines with age at arrival; as the projected number of years remaining in the workforce becomes smaller; the figure turned negative for those arriving after their mid-thirties. For immigrants with lower levels of education, the estimated net present value was much smaller initially and turned negative at an earlier age (National Research Council, 1997, pp. 328-330). Immigrants arriving after age 21 also do not themselves add to costs of public education in the receiving country (although, if they have them, their children would). In cases where immigrants are educated in the origin country, the receiving country benefits from the investment without paying for it, creating a distortion in the expenditure estimates.

Relationships between immigrant characteristics and fiscal impact were quantified by Dustmann and Frattini (2014) for the UK case, where immigration patterns have been quite different from the patterns in California and New Jersey during the 1990s and from the U.S. experience in general. Recent history in the United Kingdom has seen the arrival of large numbers of foreign-born individuals near the beginning of their productive working years, after completion of their full-time education. When formal education is financed by the countries of origin, a considerable savings—or, perhaps more accurately put, a return on investment made by others—is realized by the receiving countries. Dustmann and Frattini (2014) used an annuity-based quantification strategy that takes into account these “savings” to the destination country, showing how they increase along with the duration of stay in the receiving economy. In the UK case (and unlike the U.S. case), immigrants are on average also more educated than the native-born, although levels of education (absolute and relative) displayed by immigrants have changed over time and differ greatly by country of origin.3

Accounting exercises such as those presented in Chapters 8 and 9 create combined tax and benefit profiles by age and education to decompose the timing and source of fiscal effects. Forward projections build scenarios to

___________________

3Dustmann and Frattini (2014) do not differentiate between fiscal contributions of high- and low-skilled immigrants. Thus they do not estimate whether low-skilled immigrants to the United Kingdom have made positive or negative fiscal contributions.

demonstrate alternative assumptions about how changes in outlays—e.g., the use of public education and various programs (Supplemental Security Income; Medicaid; the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children; Aid to Families with Dependent Children; etc.)—and revenues change by generation and affect fiscal estimates. As discussed in Section 7.4, methodological approaches have been developed to suit different accounting objectives. For some policy questions, multigenerational costs and benefits attributable to an additional immigrant or to the inflow of a certain number of immigrants may be most relevant; for other questions, the budget implications for a given year associated with the stock, or recent changes in the stock, of the foreign-born residing in a state or nation is most relevant. For example, the latter is often what state legislators are most interested in. Sometimes the question is about absolute fiscal impacts; sometimes it is about the impact of an immigrant relative to that for an additional native-born person. Although these approaches require very different kinds of aggregations and calculations, the program (expenditure) and tax (revenue) fiscal components are largely the same.

7.2 SOURCES OF FISCAL COSTS AND BENEFITS

The first task in estimating fiscal impact of immigration, whether at the federal, state, or local level, is to identify the categories of costs and benefits that are affected. Immigrants contribute to fiscal balances through taxes and other payments they make into the system; they create additional fiscal costs when they receive transfer payments (e.g., Social Security benefits) or use publicly funded services (e.g., education or health care). The net fiscal impact that immigrants impart depends on the characteristics that they bring—their mix of skills and education, age distribution and family composition, health status, fertility patterns—and whether their relocation is temporary, permanent, or circular. It also depends on whether they seek employment on the legal labor market and on other conditions prevailing at destination locations, as well as their success in assimilating economically and socially.

In the context of benefit-cost analyses of state-specific immigration policies, Karoly and Perez-Arce (2016) identified channels through which immigration affects fiscal balances (see Table 7-1).

Benefits and costs may accrue to individuals and employers (predominantly through employment and wage impacts—see Chapters 4 and 5) or to the public sector. Among public expenditures associated with an expanding population, be it immigrant- or native-driven, schooling is often the most

TABLE 7-1 Domains and Types of Impacts of Immigration That Affect Fiscal Balances

| Domain | Impacts to Address |

|---|---|

| State Economic Output | Gross state product in aggregate and for specific industries |

| Labor Market | Employment and wages of subgroups of workers defined by education, race/ethnicity, nativity, or other characteristics |

| P-12 Education | Use of educational services and education outcomes from preschool to grade 12 |

| Higher Education | Use of public and private higher education institutions, including 2-year colleges and 4-year colleges and universities |

| Law Enforcement | Allocation of resources across specific types of state and local law enforcement activities |

| Criminal Justice System | Allocation of resources across specific types of criminal justice system costs (e.g., courts, jails, prisons) |

| Social Welfare System | Specific cash and in-kind transfer programs (may be affected by availability to unauthorized immigrants) |

| Population Health and Health Care | Health outcomes (e.g., immunization rates, communicable diseases, low birthweight babies) and health care utilization (public and private costs overall) |

| State and Local Tax Revenues | Specific sources of state and local tax revenues and tax expenditures (e.g., tax credits) |

| Other | Costs to implement adopted policies and defend them in the courts |

SOURCE: Karoly and Perez-Arce (2016).

significant one for state and local budgets.4 In multigenerational analyses where the specified time horizon is sufficiently long to capture future income returns, the cost of education in the current year is best categorized as an investment. In a single-year static analysis, public education for the school age population will appear as an accounting cost; likewise, for the older working-age taxpaying population, the cost of education incurred in previous periods will not be captured as part of the net calculation.

Beyond public education, a large number of other goods, services, and programs generate public costs at various levels of government:5 Medicare and Medicaid, Social Security and other protections, housing, prisons and courts, police services, and others—are financed through tax payments by

___________________

4 According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s State Government Finances Summary: 2013. See https://www2.census.gov/govs/state/g13-asfin.pdf [November 2016] expenditure for education comprised 35.6 percent of all general expenditure by state governments.

5 These components are itemized in detail for the panel’s federal and state fiscal estimate calculations in Chapters 8 and 9.

immigrants and the native-born. Economic conditions and the demographic profile of the immigrants determine the participation rate of immigrants in various safety net programs. A general finding for the United States has been that immigrants and their children have been less likely to use some programs (e.g., Social Security, Medicare,6 cash transfers—though this difference may diminish with length of stay), while others (e.g., bilingual education) are used more intensively. As discussed in Section 7.4, the impact that immigrants have on the cost of providing public goods and services depends on the way their use is attributed.

Ideally, models estimating fiscal impacts of immigration should distinguish between citizens and noncitizens and then, for the latter, authorized and unauthorized individuals. All subgroups make contributions to government finances (pay various kinds of taxes) and consume public services, but the levels differ. Legal status is often central to determining what services immigrants qualify for and tend to use and what taxes they are required to pay. Per capita expenditures on various programs vary by documentation status and are therefore directly affected by policy.7 Undocumented individuals may make retirement-related payments (e.g., Social Security, Medicare); some will never benefit while others may receive partial benefits or later become citizens and enjoy full benefits.

Safety net programs are aimed at low-income families, children, and the elderly, but immigrants do not have access identical to the native-born, due to restrictions imposed by law. Unauthorized immigrants and individuals on nonimmigrant visas are not eligible for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, nonemergency Medicaid, Supplemental Security Income, or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families. The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 and the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 introduced additional restrictions. The former made lawful permanent residents and certain other lawfully residing immigrants ineligible for federal means-tested public benefit programs (such as Medicaid) for the first 5 years after receiving the relevant status. The latter statute included a provision intended to prevent

___________________

6 For example, using Medical Expenditure Panel Survey to determine medical expenses, Zallman et al. (2015) calculated that, from 2000 to 2011, unauthorized immigrants contributed $2.2 to $3.8 billion more than they withdrew annually from the Medicare Trust Fund—creating a total surplus of $35.1 billion. This surplus, just for those 11 years, was estimated to have accounted for 1 additional year in the current projection in which the Medicare program remains solvent through 2030.

7 A report by the Congressional Budget Office in 2015 titled How Changes in Immigration Policy Might Affect the Federal Budget is available at http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/49868-Immigration.pdf [November 2016]. The report lays out how policy change scenarios affecting the status of the currently unauthorized population would affect the federal budget.

states from extending in-state tuition benefits to unauthorized immigrants.8 Prior to the enactment of these laws, authorized immigrants had access to public assistance and education benefits that were by and large equal to the access of citizens. U.S.-born children of immigrants remain eligible for all programs because they are citizens.

Borjas (2011) examined poverty and program participation among immigrant children9 using 1994-2009 Current Population Survey (CPS) data on cash assistance, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits, and Medicaid received by households. The study divided children into four groups: (a) those who have one immigrant parent (mixed parentage); (b) U.S.-born children who have two immigrant parents; (c) foreign-born children who have two immigrant parents; and (d) U.S.-born children with U.S.-born parents. The analysis revealed that, even though poverty rates10 decreased for children with two immigrant parents between 1996 and 2000, they have risen since 2007. Among the four groups of children, the poverty rate is highest for foreign-born children with two immigrant parents. Children of mixed parentage exhibit poverty rates that are not significantly different from those of children of native-born parents. Similar conclusions can be drawn from the figures on program participation rates. U.S.-born children with two immigrant parents have the highest program participation rates among the four groups, which is not a surprising outcome as their parents are likely to have lower income and, since they are native-born, they are eligible for various safety net programs.

It is more difficult to estimate expenditure levels for unauthorized immigrants, which adds an element of uncertainty to forward projections. Even the microdata sources from national surveys do not contain enough detail or population coverage to make these distinctions accurately for all programs, and assumptions must be embedded in the estimates about numbers of unauthorized citizens and about their impact on program usage.

7.3 STATIC AND DYNAMIC ACCOUNTING APPROACHES

New immigrants affect governments’ fiscal balances almost immediately upon arrival—by paying sales, income, and other kinds of taxes and

___________________

8 According to the National Conference on State Legislatures, 18 states have passed legislation since 2001 extending in-state tuition rates to undocumented students who meet a set of requirements. One state, Wisconsin, revoked its law in 2011. See http://www.ncsl.org/research/education/undocumented-student-tuition-overview.aspx [November 2016].

9Borjas (2011) defined immigrant children as those who are foreign born and migrate to the United States with their foreign-born parents and those who are U.S. born to one or two immigrant (foreign-born) parents.

10 The poverty rate is defined as the fraction of children in a particular group that is being raised in households where family income is below the official poverty threshold.

by using schools and other services. Impacts compound subsequently, over extended time horizons. State legislators or local school districts may be most concerned about the extent to which immigrants affect current and near-term budgets. Others—policy makers concerned with the long-term solvency of a government program or with multiyear budget projections or a researcher studying long-run economic growth—may be more interested in life-cycle impacts that take place over many decades. The appropriate analytic framework, each requiring specific kinds of data and entailing specific sets of assumptions, is dictated by the temporal concept most relevant to the question at hand. Additionally, while many analyses have attempted to estimate the fiscal impact of all foreign-born individuals or immigrant-headed households currently in the population, it is often more relevant for policy debates to estimate the net impact of new immigrants, since the rate and composition of new arrivals is presumably what policy will affect. It is conceptually muddled to bundle the impact of immigrants who arrived in different historical periods, who may be very different in terms of the way that they have been integrated into society and the economy.

The two basic accounting approaches to estimating fiscal impacts, one static and the other dynamic, capture distinct but connected aspects of immigration processes. The static accounting approach is conducted for a specific time frame, often a tax year, in which contributions by immigrants to public finances—in the form of taxes generated directly by them or indirectly by others (in practice, most analyses are limited to the former)—are compared with expenditures on benefits and services supplied to that population. Such an approach might be used, for example, to answer questions such as, “in California, how much did the foreign-born and their dependents add to tax revenues, and how much did they cost in terms of government expenditures last year?” And, “how much did the grown children of immigrants (and their dependents) add in tax revenue and cost in terms of expenditures last year?” Dynamic accounting approaches, in contrast, compound costs and benefits over extended time periods. This is done by computing the net present value of tax contributions and government expenditures attributable to immigrants—and in some analyses, their descendants—projected over their life cycles. Dynamic analyses involve modeling the impact of an additional immigrant on future public budgets and are useful for addressing questions such as, “over the next 50 years, what will be the impact on fiscal balances if x immigrants with a given set of characteristics y enter the country?” In both static and dynamic estimates, difference between immigrants and natives tend to be much larger on the tax revenue side than on the benefits cost side, though the second generation catches up quickly and eventually pays as much or more than the native–born population in general (National Research Council, 1997, p. 314). The earnings and tax profiles for the third generation are more or less the same as for the native population over all.

A static analysis may cover a single year or be repeated for cohorts across a number of years. To a large extent, results are driven by the composition of immigrants in terms of age, education, and other factors, relative to that of the native-born.11 As described by Preston (2013) and Dustmann and Frattini (2014), immigration can affect static estimates of the public budget constraint in a range of ways because, on average, they pay taxes and consume public services differently from the population as a whole, alter the taxes paid or services consumed by the native-born, and may affect the cost of providing services to natives. A single-year static model may provide a reasonably accurate basis for future projections in a steady state with stable immigrant rates and characteristics. However, historically, this steady-state assumption has not been met because generations of immigrants differ greatly in place of origin, age, skills, education, and other relevant characteristics. Thus, if a static calculation examines the impact of all foreign-born, it will combine people with highly varying characteristics, giving an “inaccurate picture of the impact of any particular generation of immigrants” (National Research Council, 1997, p. 297).

Dustmann and Frattini (2014) used a repeated cross-sectional approach to estimate the net fiscal contribution over the period 2001-2011 for immigrants who arrived in the United Kingdom after 2000. This kind of analysis answers the question “What has been the net fiscal contribution of immigrants who arrived in a country after a given point in time?” (Dustmann and Frattini, 2014, p. 598). Because the analysis is retrospective, data on actual tax payments and public expenditures can be used to estimate the fiscal impact of a cohort of individuals from the start of residency onward to the present in a way that minimizes dependency on underlying assumptions. The analysis does not require projecting income levels, educational costs, or government budgets in future years for which data do not yet exist.

Kaczmarczyk (2013) summarized these advantages of the static approach:

- Conceptual simplicity—it is relatively straightforward to explain the results of the static approach, as they are observed flows of revenues and costs associated with immigrant-driven expansion of the population.

- Use of historical data—no detailed population projection data are needed.

___________________

11 See The New Americans (National Research Council, 1997, pp. 257-263) for a formal description of the steps involved for a static annual fiscal impact analysis. See Dustmann and Frattini (2014) for a detailed description of the repeated cross-sectional approach, and see Chapter 8 for details of the analyses used for this report.

- Eased reliance on assumptions—there is no need to impose strict assumptions about future trends of immigrant and native populations (e.g., size and education, age composition) and about government (e.g., fiscal balance or change in immigration policies).

Among the disadvantages, he lists the following:

- Results lack a forward-looking perspective, which is often critical for informing policy.

- Static analysis has less capacity to assess the long-term consequences of recent migration—for instance, to project how immigrants will use services or pay taxes over their lifetimes, consequences that are particularly important when the immigrants’ demographic profiles differ significantly from those of the native population.

- It is difficult to incorporate fiscal impacts of a proposed change in immigration policy unless the annual snapshots are repeated indefinitely, in which case the information will still be retrospective.

In contrast to static fiscal impact estimates, dynamic analyses are designed to project future contributions to public finances and costs of public benefits programs. Such models attempt to account for: (1) future population growth, including the components driven by natural increase and by net migration; (2) projected changes in employment and wage profiles; and (3) government spending and tax rates. Immigrants can affect public finances by changing the age, skills, or other elements of the composition of the population. Assumptions are required about the rate at which immigrant earnings converge with native counterparts for various age/education cells after arrival (see Chapter 3 for evidence on this) and about future fiscal balances (see discussion below in this section).

Using a dynamic intergenerational approach based on mid-1990s data for the United States, The New Americans estimated that the net present value of the lifetime fiscal impact (combined federal, state, local) was −$13,000 for an immigrant with less than a high school education, +$51,000 for an immigrant with a high school education; and +$198,000 for an immigrant with more than a high school education (National Research Council, 1997, p. 350). Lee and Miller (2000), updating The New Americans and using a similar methodology, showed that the initial fiscal impact of most immigrants (and their households) is negative as a result of low earnings upon arrival and the costs associated with schooling of their children. After about 16 years, the impact of a “representative” immigrant turns and remains positive. The dynamic approach is designed to capture these full life-cycle impacts; by contrast, results from the static approach

will reflect the fiscal impact at a moment in time of the entire distribution of foreign-born of different ages and arrival dates.12

An attractive feature of dynamic fiscal projections is that their structure allows the effects of proposed or current policies to be simulated. Different scenarios can be run, for example, to project the impact of a rule change allowing the wages of unauthorized workers to be reinstated on their record of earnings upon obtaining a valid Social Security Number, or the generational consequences of cutting Social Security benefits versus raising payroll taxes. Fiscal impacts of visa policy changes that may affect the age and skill mix in the stock of foreign-born and the population as a whole can also be projected.13 The mix of visas—working, student, family reunion, seeking asylum—under which immigrants enter will affect both the employment and taxes generated from immigrants and the benefits used. Immigrants entering the country on work visas can reasonably be expected to have more favorable labor market outcomes than those arriving for family or humanitarian reasons. Those entering with work and student visas also have limited access to benefits such as social housing and unemployment compensation and are more likely to generate tax revenues in current and future periods. Ideally, data would allow the flow of the foreign-born population to be decomposed by entry category, since any projected changes in the distribution by these categories would be expected to have a direct impact on fiscal outcomes.

Dynamic analyses vary in terms of how and if various mechanisms through which immigration can impact the economy and the subsequent fiscal picture are incorporated. The New Americans (National Research Council, 1997) and Lee and Miller (2000) developed “partial equilibrium” analyses in the sense that they only estimate direct fiscal effects attributable to immigrants themselves. They do not take into account indirect (general equilibrium) impacts of immigration on wages, or on labor force participation and occupational choices of the pre-existing population—mainly because these factors are very difficult to estimate credibly. Over time, the reshaping of the labor force, the expansion of capital stock, and any impact

___________________

12Figure 7-1 illustrates the fiscal profile by age for a static, cross-sectional analysis of the United States based on 2012 data.

13 Sometimes, past policies can also be examined to inform possible impacts. Hansen et al. (2015) forecasted the impact of immigration on public finances for Denmark by taking advantage of the natural experiment that occurred there around the year 2000 as a result of shifting from a heavily family reunification–based policy to a skills and employment–based policy. Over the period immediately after the policy shift, from 2000 to 2008, the unemployment gap between native-born in Denmark and immigrants narrowed and public finances improved. More generous social safety net benefits in Denmark were also shown to lead to more negative fiscal impact than in the United Kingdom for low-skilled immigrants (Dustmann and Frattini, 2014).

on productivity and economic growth brought on by immigration will affect public finances through conduits such as corporate taxes and taxes paid by natives. Therefore, assumptions about central growth rates must also be made (see Section 6.5) for general equilibrium analyses. Immigration also produces other indirect effects, such as on housing ownership and rental markets which, in principle, could be integrated into dynamic fiscal models. Also, behavioral responses—such as when an influx of cheap child care or housekeeping service workers changes the labor supply decisions by native workers—can also be studied.14

Likewise, static analyses—particularly for a single year—are, by their very structure, partial equilibrium analyses; future periods must be considered in order to incorporate most secondary or indirect effects. Hansen et al. (2015) included general equilibrium effects in their dynamic projection using population register data on both first- and second-generation immigrants. Their model “estimates long term economic activities and sustainability of economic policy” on the basis of submodules projecting the population (incorporating fertility rates, mortality rates, and inward and outward migration); future age-, gender-, and origin-specific education levels of that population; and future proportions of the population within and outside the labor force (Hansen et al., 2015, p. 8).

Storesletten (2003) analyzed the United States using a general equilibrium approach, in the sense that labor supply and payments to the factors of production were treated as endogenous in his model, which was specified to incorporate differential impact of immigrants by age, employment status (working or not), and skill level. In such analyses, variation in the fiscal impact of immigration is dictated less by the size of the immigrant population than by its composition. Chojnicki et al. (2011) used a general equilibrium model to analyze the impact of immigration on social expenditure and the public budget in the United States for the period 1945-2000. They found that immigration had a large positive impact on public finances, relative to a no-immigration scenario, during that period—mainly due to immigrants’ younger age structure and higher fertility rates relative to the total population. These demographic effects reduced transfer payments by lowering the old-age dependency ratios (see Chapter 2).

To summarize the preceding discussion, among the advantages of dynamic fiscal estimation models are the following (Kaczmarczyk, 2013):

- A forward-looking perspective providing a projection of the fiscal impacts of immigration in a life-cycle framework that captures net positive expenditures for younger and older individuals on educa-

___________________

-

tion and health care and net positive revenues during working years when tax payments are highest; and

- capacity to assess the impact of immigration on structural changes resulting from population aging (e.g. pension system and its sustainability).

Among the disadvantages of the dynamic accounting approach (or, really, any analytic attempt to estimate future consequences) are the following:

- Outcomes depend strongly on the set of assumptions made about future trends in income and population growth (which depends on projections of fertility rates, life expectancies, and return migration rates), worker productivity, labor market participation rates for immigrants and natives, and government-established tax rates and program spending levels; and

- within the generational accounting framework, huge degrees of uncertainty are introduced due to unknown future deficit and debt profiles. In addition, as noted in The New Americans (National Research Council, 1997, p. 256), “dynamic fiscal accounting requires specification of a social rate of discount, so that future tax revenues and spending needs can be compared in terms of current dollars.”

The literature has identified a range of policy-relevant questions for which fiscal impact studies are required: For example, what is the marginal impact of an incremental increase in immigration (i.e., the impact of one additional immigrant); the per capita impact of an increased rate of immigration; the future impact of an immigrant cohort with a given demographic profile; the impact of an additional 100,000 immigrants over current levels; or the consequences of changing numbers or types of visas/entries (e.g., skill based instead of family centric)? Or, alternatively, what has been the net fiscal contribution of the foreign-born who arrived in a country after a given point in time; and how have the net impacts varied by level of government? Defining the question or scenario of interest is clearly the prerequisite to selecting an appropriate modeling framework.

7.4 SOURCES OF UNCERTAINTY: ASSUMPTIONS AND SCENARIO CHOICES IN FISCAL ESTIMATES

Estimating fiscal impacts is data intensive and methodologically complex. Even if accurate microdata were available on the characteristics, taxes paid, and program usage for all immigrants and natives, decisions must still be reached about how to treat various kinds of costs and benefits and—in the case of dynamic projections—the uncertainty of future economic and

policy trends. When data are lacking, or when projections into the future are required, assumptions must be made about program participation rates and policy changes. Dynamic projections rely more heavily on assumptions than do static models but, as identified below, modeling choices are required in any fiscal analysis.

Unit of Analysis: Individuals Versus Households

A preliminary step in all fiscal analyses is to select the unit of analysis. A decision must be made whether tax payments and expenditures based on program use will be estimated for households as a unit or for each individual. Ideally, this decision would be dictated conceptually by the budget item that is being apportioned. For instance, health and education expenditures accrue for individuals while some taxes and benefits, including most cash-transfer programs, are based on household characteristics. Data realities sometimes prevent the unit of analysis choice from matching the ideal.

For dynamic analyses, the household unit of analysis is problematic because families’ living arrangements change over time through marriage, divorce, the departure of grown children, the arrival of additional family members from abroad, return migrations to the country of origin, and deaths. Dynamic fiscal accounting based on households becomes exceedingly difficult “as (often arbitrary) forecasts of family dissolution and formation become necessary” (National Research Council, 1997, p. 255). Further complicating the situation is the increasing prevalence of nonimmigrants in immigrant-headed households, and vice versa. Because households are not stable over time and because the costs and benefits originating in mixed households often need to be divided between native-born and foreign-born members—as opposed to having to ascribe them exclusively to one group or the other—the individual unit of analysis is more flexible and empirically feasible for dynamic analyses. Perhaps for these reasons, this was the approach taken in the dynamic projections in The New Americans (National Research Council, 1997).

For cross-sectional analyses, the choice of unit of analysis is somewhat more difficult. Although the individual is used for the baseline scenario in its dynamic analyses, The New Americans (National Research Council, 1997, pp. 255-256) states, “Since the household is the primary unit through which public services are consumed and taxes paid, it is the most appropriate unit as a general rule and is recommended for static analysis.” While this logic is sound, a case can also be made for again selecting the individual as the primary unit. Aside from the value of being consistent with the method used for the dynamic analysis, there is, even at a point in time, the issue of how to define an immigrant household: by head of household, by requiring both parents in a two-parent household to be foreign born,

etc. Assigning the public cost of children to parents as individuals allows the costs to be attributed to multiple immigrant generations when called for by the situation (e.g., cases in which households consist of one first generation adult and one native-born adult). Moreover, the static analysis in this report extends beyond that used in The New Americans by repeating the cross-sectional estimates over 20 years, a period more than long enough to see household composition change.

Accounting for the Second Generation

The treatment of native-born individuals with foreign-born parents is an issue in both static and dynamic approaches.15 In forward-looking projections, the logic for including second generation effects is straightforward: Even if children of immigrants are native-born citizens, they generate costs and benefits to the receiving country directly as a result of their parent(s) having entered the population. Children of immigrants, whether born in the origin or destination country, consume public education services while they are of school age, and they may be expected to contribute to the net fiscal balance in a positive way by paying taxes later in their lives. In a cross-sectional analysis, this life-cycle effect will be driven by current demographic composition. It will be captured only to the extent that data are detailed enough to reveal the grown children of immigrants who have graduated into tax-paying adults at a point in time. Most of the flagship population data sources in the United States, including the Decennial Census (after 1970) and the American Community Survey (ACS), which replaced the Decennial Census long form, do not identify second generation respondents.16 Fortunately, information on parental birthplace has been available since 1994 from the CPS, and these data are used in the state and local level analysis in Chapter 9 and at various points in the national analysis in Chapter 8.17

___________________

15 Beyond the conceptual question, as discussed below, capturing the relevant population is complicated by lack of data in most Census Bureau datasets on parental place of birth. This makes identification of second generation individuals difficult once they have left the immigrant-headed household.

16 See Massey (2010) on analytic limitations created by the absence of data on parents’ birthplaces in the Decennial Census and the ACS. As just one example among many, the ability to identify second generation respondents is necessary for estimating tax revenues contributed by the children of immigrants after leaving the education system (and leaving immigrant-headed households) and entering the labor market. If not accounted for, this biases estimates of the net fiscal contributions of immigrants in a negative direction.

17 As noted by Massey (2010), relative to the ACS, the sample size of the CPS is quite small, which means that the Census Bureau data sources only yield stable estimates for large immigrant groups and highly aggregated geographic areas (e.g., large-population states and at the national level).

Dynamic cohort analyses attempt to capture second and later generation effects but must make assumptions about return immigration rates and economic assimilation that affect future employment and earnings profiles.18 For intergenerational projections, assumptions must be made not only about the future flow of immigrants into the country but also about the education and skills that they will bring or will acquire upon arrival. Predicted tax payments and benefit expenditures will differ dramatically for a high-education versus a low-education scenario. For immigrants that arrive after age 25, it is generally assumed that they will maintain the education level observed on arrival, so no further predictions about their education have to be made. For immigrants arriving at younger ages, their future final educational attainment is typically predicted as a function of parental education. And, when estimating the marginal cost of immigrants to education budgets, the children of immigrants are typically included, independent of birthplace. In the research used as an input to the fiscal projections in The New Americans, Lee and Miller (1997) found that including projected lifetime impacts of children of immigrants into the analysis provided a strongly positive fiscal contribution regardless of their parents’ educational attainment. That said, the initial estimates of fiscal contribution for immigrants themselves (prior to factoring in second generation effects) were highly dependent on educational attainment. Immigrants with education beyond high school were projected to add positively to net present value while those with lower levels of education caused a net fiscal loss. Similarly, Storesletten (2003) found the net cost to society of immigrants to be highly variable, with the difference between amount paid in taxes and amount of public goods and services used over the life cycle ranging from a $36,000 cost to a $96,000 benefit, depending on the individual’s education level.

As noted above, choices must also be made about how to handle the increasingly common cases of children of mixed (one native-born, one foreign-born) couples. The literature includes analyses in which the children are put in one group or the other and analyses in which they are split between the two groups. The New Americans assigned native-born children of native/foreign-born couples by the birth status of household head (National Research Council, 1997). Dustmann and Frattini (2014) considered children of mixed couples as half natives and half immigrants and allocated the costs accordingly. As will be seen in Chapters 8 and 9, how the children of immigrant-headed households are treated can have a large impact on fiscal estimates; details about how second generation individuals are handled in the national and state and local level estimates are provided in those chapters.

___________________

18 The role of educational attainment assumptions for the second generation is discussed by Blau et al. (2013).

Stay and Return Rates of Immigrants

Population projections underlying dynamic fiscal projections must incorporate estimates of survivorship, fertility rates, and net in-migration. Since not all foreign-born individuals who come to the United States stay long term, return migration must also be taken into account. Immigrant return rates and length-of-stay patterns affect the population demographics and, in turn, a receiving country’s fiscal picture. A student may return home after completing a degree. A person entering on a work visa may do the same after completing a job. Historically, circular migration has occurred as well, especially for people who worked seasonally in the United States, many of whom were unauthorized.19 When foreign-born individuals move to a country to work but then return home, they are less likely to ultimately tap into expensive late-life benefits such as Social Security and publicly funded medical care. Yet they may enroll in pension systems and begin contributing income and payroll taxes immediately. If immigrants are temporary and do not claim pensions or other post-retirement benefits from the destination country, their net fiscal contribution is likely to be very positive. In contrast, immigrants who stay will typically create system costs later in life.

Circular and return migration patterns, and assumptions about them, are especially important for forward-looking, dynamic fiscal estimates. Most obviously, for the foreign-born who return or circulate out, the second generation impacts are not in play, unless they have U.S.-born children who stay or eventually return. Therefore, assuming that all foreign-born individuals who appear in the data will stay until death can lead to large errors in fiscal (and economic) impact studies. The population projections underlying the dynamic model in Chapter 8 assume that children of immigrants ages 0-19, whose parents emigrate, leave with them, even if they are U.S. born. Largely following the Census Bureau methodology, immigrants are assumed to have a much higher risk of emigration during the first 10 years after arrival in the United States. Fiscal projections will be affected especially if the characteristics—for example, age, skill, earnings—of out-migrants are systematically different from averages for all foreign-born individuals such that selection effects come into play.

Conceptually, then, the ideal fiscal analysis would factor in return rates and separately track the characteristics of permanent and temporary immigrants. Data constraints typically make this impossible, so assumptions are made based on partial information. The baseline scenario in the dynamic models developed for The New Americans was that 30 percent of

___________________

19Massey et al. (2015) argued that return and circular migration among undocumented immigrants (primarily from Mexico) has dropped sharply in response to the massive increases in border enforcement of the past two to three decades.

immigrants later emigrate, taking with them all their young children; 16 percent of those born in the second generation were assumed to emigrate with their parents. Such assumptions about return migration affect only the projected numbers of immigrants in the country; secondary effects in the labor market and in earnings profiles reflecting different characteristics and self-selection patterns among stayers and leavers (which, historically, is the norm) are not captured.

Storesletten’s (2003) intergenerational model incorporates estimates of out-migration rates and post-migration take-up rates of social benefits to demonstrate how fiscal contributions are affected in different scenarios. One notable finding for the United States was that return migration of high-skilled immigrants under age 50—quite common during the first few years after arrival—decreases their time-discounted fiscal contributions. Kırdar (2012), studying the German pension and unemployment insurance systems, found that building immigrant return decisions into his model as an endogenous choice increased the net expected gain to the destination country’s finances. (Storesletten did not address selection effects differentiating career paths of temporary versus permanent immigrants.) This is explained by the observation that those most likely to be beneficiaries later on—low income immigrants—are also the ones most likely to return first due to inferior labor market outcomes. A summary report by OECD (2013) on the fiscal impact of immigration also found important differences for most developed countries in the tax contribution and benefit use patterns of native-born populations, permanent immigrants, and temporary immigrants.

Indirect/Secondary Fiscal Impacts

Most intergenerational fiscal projections are limited by a partial equilibrium perspective. That is, they focus on first-order tax revenue and program spending effects—those discussed above—while assuming that no market or behavioral changes take place in response to new immigrants. Labor market displacement or enhancement, capital adjustments, housing price pressures, etc., are not factored in. The same is true for the static approaches described above where, for example, any labor market displacement of natives—and in turn the impact on the tax contributions they make and public services they use—have been largely ignored.

Second-order market effects do clearly occur, and several studies noted above attempt to account for some of them. As discussed in Chapter 6, immigration-induced expansion of the population can increase housing prices and rents; low-skilled migrants willing to work in house-cleaning or child or elder care services enable native workers, particularly high-skilled

women, to supply more labor to the market, which affects tax contributions. In a comprehensive analysis, these ripple effects in the economy would be accounted for; however, due to the complexity of operationalizing a general equilibrium approach into the accounting framework, they typically are omitted. The fiscal impacts literature has generally concluded that these kinds of impacts are minor relative to overall economic activity. However, even if overall (nationwide) labor market effects of immigration are likely to be small, whether the direction is positive or negative, the impact may be large in specific geographic areas or types of markets.

Karoly and Perez-Arce (2016) provided a policy-relevant example of main and secondary impacts, using college tuition as the case study. Table 7-2 itemizes the direct and secondary economic and fiscal effects that she found associated with a policy granting in-state tuition benefits to undocumented immigrants. Such a policy may incentivize foreign-born individuals to come to the United States (or to a particular state) to take advantage of the benefit—a direct cost, but it may also create more high-skilled workers who, at least in time, would raise wages and in turn tax revenues, improving the fiscal picture.

TABLE 7-2 Multiple Impacts of Granting Eligibility to Undocumented Immigrants for In-State Tuition

| Potential Main Impact | Potential Secondary Impacts |

|---|---|

| Increased Number of Unauthorized Immigrants | Decreased wages of unskilled workers Increased economic output/decreased price of some services Increased tax revenue and increased government expenditures |

| Increased Educational Attainment of Unauthorized Immigrants |

Effects through changes in individual human capital:

If demand for subsidies exceeds supply:

If net increase in subsidized enrollments:

If net increase in college-educated versus noncollege-educated population and labor supply:

|

SOURCE: Karoly and Perez-Arce (2016).

Allocating Costs of Government-Provided Goods and Services

Both static and dynamic fiscal analyses must make assumptions about how to allocate government spending among newly arrived immigrants (authorized and not), established foreign-born residents, and the native-born. To do this, it is necessary to consider how broadly and intensively immigrants use public services and transfer benefits. Take-up rates by the foreign-born for various programs, described in Chapter 3, become important parameters in fiscal estimates. The models in Chapters 8 and 9 necessarily include such parameters for assigning costs. A default assumption might be that immigrants’ use-rate is equal to that for the population, so that they account for the same per capita consumption of public services as do natives. If possible (that is, if data exist), it is preferable to consider to use patterns of the many government-provided goods and services on a case-by-case basis, as the nature of their consumption is highly variable. Differences in the characteristics of immigrants and native-born individuals also come into play. Obvious examples for which use patterns vary for different groups are English as a second language (ESL) classes taught in schools or translation services offered in hospitals. Since these services are used disproportionately by immigrants, it may make sense to attribute a higher average cost to recent arrivals than to established foreign-born or native-born individuals.

For some services, such as education and health care, data may reveal that the total cost of provision is roughly proportional to the number of recipients. This argues for assigning costs on a pro rata, or per capita average cost, basis in the accounting exercise (Dustmann and Frattini, 2013). In other cases, the marginal cost of provision may differ significantly from the average cost. Publicly provided goods that depend only partly on the size and composition of the population, such as public infrastructure, public administration, and police forces are examples. In the case of “congestible public goods,” the marginal costs of additional population (immigrant or native) may be higher or lower than average cost but is greater than zero. Such might be the case if a district’s schools were operating at or above capacity and an influx of immigrants created the need to build new schools and hire additional teachers. Proper accounting of congestible goods requires information—or lacking appropriate data, assumptions—about how the provision and consumption of goods and services change with the share of immigrants in the population.20 Most studies attribute the costs of these kinds of goods equally across the whole population—that is, propor-

___________________

20 For computational feasibility, analyses frequently assume that the quality and level of services are fixed. Thus, with a flow of immigrants added to the population, total costs must increase to maintain that quality level for most goods and services. Income transfers, for example, are more like private goods, and per-person spending must be maintained if service levels for all are to be held constant (National Research Council, 1997, p. 256).

tional to the number of recipients (Rowthorn, 2008). Whether or not there is resource strain and congestion—with resulting impacts on the sustainability of public services or population welfare programs—relates closely to the way the marginal analysis is framed. Congestion may be irrelevant when considering the current fiscal year impact for school or infrastructure budgets created by an additional immigrant. In contrast, congestion is a central concern when considering long-term costs associated with a growing population. Similarly, the marginal cost calculus will be quite different when considering the marginal addition of one immigrant at a point in time versus the addition of many thousand immigrants over a period of time.

“Pure” public goods—goods defined by the trait that their value and availability is not diminished by additional users—also enter fiscal estimates. Such goods, at least within a range, are unaffected by population size. National defense, which accounts for about 18 percent of the U.S. federal budget, is a classic example. The marginal increase in these costs due to immigration is, at least in the short run, zero or close to it. Other candidates to be treated as pure public goods include government administration and interest on the national debt. Dustmann and Frattini (2014, p. 7) contrast pure versus congestible public goods:

‘Pure’ public goods and services are not rivals in consumption and the marginal cost of providing them to immigrants is likely to be zero. For example, the expenditure for defence or for running executive and legislative organs is largely independent of population size. ‘Congestible’ public goods and services are—at least to some extent—rival in consumption, so the marginal cost of providing them is unknown, although probably smaller than the average cost and positive. For example, the cost of fire protection services, waste management and water supply may indeed increase with the size of the resident population. . . .The ideal—if data were limitless—would be to measure the marginal cost of providing each public good and assign it to every new immigrant.

In the case of pure public goods, immigration has the beneficial effect of allowing fixed program costs to be spread over a greater number of taxpayers—thereby lowering per capita costs for the population in general (Loeffelholz et al., 2004). In fiscal accounting exercises, this savings would therefore enter as a reduction in the per capita tax burden imposed on current native residents (and established, taxpaying immigrants). One could challenge this treatment for very long run analyses by arguing that, over time, public goods such as defense spending have been correlated with gross domestic product (GDP) and population size.

The fiscal analyses in Chapter 8 present alternative scenarios, allocating the costs of pure public goods to natives only in one subset and to everyone

in another (that is, spreading the costs equally across the entire population, including the arriving foreign-born). To understand this assumption, it is useful to consider types of expenditure that are the opposite of pure public goods—for example, an ESL program. To a first approximation, there would be no costly ESL programs if not for the arrival of new immigrants. This suggests that one should ascribe the program’s cost to them alone. Putting aside economies of scale in providing such programs, an additional immigrant increases the total cost of providing ESL education. By the same logic, the arrival of an additional immigrant does not change in any meaningful way the cost of defending the country; in fact, as pointed out above, it lowers the per capita cost of a given amount of defense (as the numbers of aircraft carriers, etc., remain the same) as long as the immigrants contribute something, even if it is below average, to the overall size of the tax base. For analyses estimating the fiscal impact of other kinds of immigration scenarios—for example, for large numbers of arrivals taking place over a multiyear period—the zero marginal cost assumption becomes less tenable.

Since public good items such as national defense represent a large part of the federal budget, the difference between allocating expenditures on them pro rata or at a zero marginal cost will have a very large impact on fiscal estimates. In fact, such assumptions are likely to swamp the impact of most of the other assumptions and data issues that arise in fiscal impact analyses.

In the Dustmann and Frattini (2014) analysis of UK fiscal balances for the period 2001-2011, the total net contribution of all immigrants ranged from −£76 billion (2011 prices) under the average cost scenario (public goods costs are assigned to immigrants pro rata) to +£27 billion under the marginal cost (public goods costs are assigned to natives only) scenario. These are large numbers in absolute terms but, relative to the size of the overall economy, still fairly modest: −0.7 percent and +0.3 percent of UK GDP respectively. The fiscal analysis in The New Americans showed similarly contrasting estimates made under marginal versus average cost assumptions, albeit for a forward-looking projection:

If all the expenditures we categorize as provision of public goods (military expenditures are the leading case) were instead treated as private or congestible goods, so that a per capita cost is allocated to immigrants and their descendants, then the average NPV [net present value] would drop from +$80,000 to –$5,000, just slightly negative, or by $85,000, thus identifying public goods as contributing powerfully to the result. A similar calculation shows that treating congestible goods (roads, police, etc.) as public goods with zero marginal costs would add $80,000 to the baseline NPV, for a total of +$160,000 (National Research Council, 1997, p. 346).

A static analysis by Passel and Fix (1994), in which the marginal cost of providing a range of public services to immigrants was assumed to be zero, estimated the net fiscal impact of immigration in the United States to be +$25 billion for 1992. Replicating this analysis—but changing the allocation assumption to one in which the marginal cost of providing public services to immigrants is set equal to the average cost—Borjas (1994) re-estimated the net annual fiscal impact associated with immigration in the United States to be about −$16 billion.

Some public expenditures pose additional, interesting analytic issues. One is law enforcement. While data limitations are significant and the research on the topic undeveloped, a review of recent literature on crime and immigration (commissioned by the sister panel to this one) reached a number of conclusions—among them the following from Kubrin (2014):

- Immigrants are generally less crime prone than their native-born counterparts.

- However, this individual-level negative association between immigrants (relative to the native-born) and crime rate appears to wane across immigrant generations: The U.S.-born children of immigrants exhibit higher offending rates than their parents.

- Areas, and especially neighborhoods, with greater concentrations of immigrants have lower rates of crime and violence, all else being equal.

- Theories to explain this negative association between crime rate and immigration have not been sufficiently empirically evaluated.

These findings suggest that a practical starting point for treating crime and law enforcement is to assign costs on a pro rata, or per capita average cost basis. However, with more granular data, it could be reasonably argued that a smaller-than-average per capita cost should be assigned to new immigrants.

Border enforcement is a special subcategory of law enforcement, and the literature is quite unresolved about how to treat its cost. The Secure Fence Act of 2006 authorized hundreds of additional miles of fencing along the U.S.-Mexico border. The annual budget of the Border Patrol increased from $363 million in 1993 to $3.5 billion in 2013. Since the creation of the Department of Homeland Security in 2003, the annual budget of Customs and Border Protections, which includes the Border Patrol, doubled from $5.9 billion to $11.9 billion in 2013. Spending on Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the interior-enforcement counterpart to Customs and Border Protections within the Department of Homeland Security, grew from $3.3 billion since its inception in 2003 to $5.9 billion in 2013. The budget for Enforcement and Removal Operations has increased from

$1.2 billion in 2005 to $2.9 billion in 2012.21 These are large budget increases for individual programs, but they represent only a very small fraction of government expenditures, and so they can only have a limited effect on estimates of per capita fiscal impacts.

There are at least two defensible options for allocating the cost of these programs. Probably the least controversial default option is to divide the cost among all, foreign-born and native-born. The foreign-born who have been in the country for a long time have pretty much the same things to gain and lose as the native-born. Conceptually, it might make sense to treat recent immigrants, especially those still trying to unify families, etc. differently, but to try to slice it that fine in the actual projections would be very difficult.

Alternatively, an analysis could start with the premise that unless one thinks that the bulk of the money is spent processing new immigrants or handling their visas (unlikely), this is not a cost of immigration but rather the cost of keeping immigrants out. Ascribing that cost to immigrants creates the perverse effect that the more effective the program is (or the more money devoted to it), the more expensive it is per immigrant who arrives in the United States during the period of analysis. Consider the following example: suppose that (at immense expense) U.S. border security and immigration control programs manage to seal the U.S.-Mexico border so effectively that during an entire year, only one illegal immigrant manages to successfully cross it. Using the approach in question, the billions spent on these programs would be ascribed to that one person. The more immigrants who manage to cross the border, the lower are the per capita cost of the programs. In light of these perverse consequences, it appears more reasonable to treat these programs as additional pure public goods and to not ascribe their cost to (arriving) immigrants only but to spread the cost across all residents, either including or excluding the arriving immigrants.

In a general equilibrium analysis, the question of how to distribute these costs is more complicated, as the efficacy of border enforcement affects labor and other markets throughout the economy. Massey et al. (2015), using data from the Mexican Migration Project, estimated the determinants of departure and return according to legal status. They found that, since 1986, Mexico-U.S. circular migration “has declined markedly for undocumented migrants but increased dramatically for documented migrants . . . [and] return migration by undocumented migrants dropped in response to the massive increase in border enforcement.” Return migration of documented migrants was unaffected (Massey et al., 2015, p. 1015).

___________________

21 Ewing, W.A. (2014). The Growth of the U.S. Deportation Machine and Its Misplaced Priorities. Available: http://immigrationimpact.com/2014/03/10/the-growth-of-the-u-s-deportation-machine-and-its-misplaced-priorities [November 2016].

Given the economic benefits of circular and temporary migration for work purposes,22 it is certainly possible that additional costs have been created to the economy by the increased border enforcement, beyond the narrow costs of the programs themselves in the federal budget.

Finally, if indirect impacts are also considered (see “Indirect/Secondary Fiscal Impacts” above in Section 7.4), accurate estimation of fiscal impacts would require including the contribution of immigrants to the delivery of public services, not just their consumption of these services. In a number of government service sectors (e.g., health care), recent immigrants have lowered costs because of their availability and willingness to work at a lower wage than native-born workers. This type of effect would only be detected in partial equilibrium analyses, such as most of those reviewed in Chapter 5, if, for instance, their presence in the labor market lowered native wages or reduced their employment.

Fiscal Imbalance—Dealing with Debt

For forward-looking projects such as the generational accounting model used in Chapter 8 (and in The New Americans), assumptions must be made about the government’s intertemporal budget constraint and about the tax burden across generations. To calculate the path of revenues and expenditures (and accumulating deficits), it is necessary to overcome the reality that one does not know what future fiscal balances will look like and what the level of deficit financing will be. Budgetary adjustments imposed to conform to an assumption about the debt/GDP ratio must be divided between tax increases and benefit reductions. Assumptions about how (and to what extent) net tax payments made by current and future generations cover the present value of future government expenditures and help to pay the debt can have a large impact on the estimates of fiscal impacts. In The New Americans, this assumption was handled as follows: A government “cannot let its debt grow without limit relative to the economy, as measured by gross domestic product (GDP), without losing credibility in its ability to repay and may eventually face default. To reflect this, it is necessary to assume that the ratio of debt to GDP stabilizes at some point” (National Research Council, 1997, p. 299). The baseline scenario for that study used 2016 as the time when fiscal policy would hold the debt/GDP ratio constant. Among the alternatives cited in The New Americans (National Research Council, 1997, p. 300) to the assumption that government must be in balance or that debt cannot exceed a given percentage of GDP (e.g.,

___________________

22 See Zimmermann (2014), which examines how circular migrants fill labor shortages in host countries while also encouraging the transfer of skills (“brain circulation”) from one geographic area to another.

current policy remains in place until the debt/GDP ratio hits 1.0), were the following:

- Current tax and expenditure policies will continue, causing the debt to explode over time (Auerbach, 1994; Congressional Budget Office, 1996).

- Debt/GDP ratio is stabilized immediately at its current value.

- Current policy remains in place for 10 years, after which the ratio is stabilized.

All three options can in principle be modeled (although the first would be complicated in a general equilibrium analysis in which one was trying to quantify what would happen to the economy as a result of an exploding national debt). Assuming a constant debt/GDP ratio means adjustment gets harder and harder for program costs like Medicare. Different scenarios will lead to different adjustments in taxes and benefit payments over time.

Assumptions about budget imbalances invoked in several of the Chapter 8 scenarios rely on the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO’s) fiscal forecast from its long-term budget outlook. In the past, the CBO assumed that the upper limit for debt could reach stratospheric levels of 1,000 percent of GDP (debt/GDP ratio of 10), but since 2010 the CBO has adopted a maximum ratio of 250 percent. This constraint seems likely because at that level either the cost of debt service plus whatever else the government spends exceeds the maximum amount that can be raised in taxes (this is where tax revenue reaches the top of the Laffer curve in their models) and because there is no precedent in modern history for sustaining this level of debt (the relevant precedent is the United Kingdom after the Napoleonic Wars, when the debt/GDP ratio reached about 230%). Of course 250 percent is still very high,23 and it is hard to imagine that fiscal policy will not have to change long before that ratio is reached, but any number that is chosen will be equally arbitrary.

Fiscal balance also plays a role in static analyses. For the average individual in the population, the net fiscal contribution must be negative if the country is running a deficit for the year of analysis. Therefore, as Dustmann and Frattini (2014, p. 598) pointed out, “The absolute net contributions of different populations may not be a meaningful measure of their fiscal contribution because these figures depend on the magnitude of the deficit. What is more insightful is their relative contribution in comparison to other population groups, especially as this comparison somewhat ‘eliminates’ the common deficit effect as far as it affects different groups in the same way.”

___________________

23 The current debt-to-GDP ratio (including external debt) for the United States is about 105 percent; the all-time high for the country, reached in 1946, was about 122 percent.

Appropriate Discount Rate (for dynamic analysis only)