3

Cases: Methods and Approaches for Risk Assessment and Communication

The chapters in previous editions of the National Climate Assessment (NCA) were organized around region- and sector-based topics, including the Southwest; coastal regions of the United States; and the interactions among energy, water, and land use.1 For the workshop, three panels of experts were asked to consider how the authors of the chapters on those three topics for the NCA4 might take into account the ideas about characterizing and communicating discussed in the workshop. The panelists, many of whom had contributed to the development of prior NCAs, were asked to address ways to make risk information useful for the decision makers most interested in their particular topics and improve the treatment of consequences, uncertainties, and tradeoffs.

THE U.S. SOUTHWEST

The Southwest has already begun looking across sectors and using scientific information in making policy decisions, noted moderator Kristie Ebi of the University of Washington. Gregg Garfin of the University of Arizona, Bradley Udall of Colorado State University, and Jonathan Overpeck of the University of Arizona provided their perspectives on how the NCA4 can be most helpful to that region.

Garfin offered recommendations for the process of developing the NCA4, based on his experience contributing to the development of the NCA3. He

___________________

1 For a complete list of the chapters of the NCA3, see http://www.globalchange.gov/sites/globalchange/files/NCA3_Highlights_LowRes-small-FINAL_posting.pdf [May 2016].

noted that the objectives for the NCA4, described in the planning document for the workshop, are ambitious. The document indicated that users hope the NCA4 will be, among other things, accessible, useful for decision making, easy to understand, focused on individual hazards, clear about the consequences of particular choices, accurate, and useful for making comparisons and assessing tradeoffs. Garfin said he doubts that the NCA4 can achieve all of these objectives given expected constraints in time. “If we focus on individual hazards,” for example, “we will need to reframe the NCA.” It will not be possible to address comparisons and possible consequences of alternatives at the scale of the NCA regions, he explained. This could be done using individual case studies that have a narrower focus, which he believes would be useful. Garfin offered three broad suggestions for the writing of the NCA4: developing a culture of risk assessment, providing more author support, and taking users’ perspectives as a starting point.

With respect to his first suggestion, Garfin said that the NCA4 writing teams should be given instructions on how to frame risk, and he suggested several strategies for making the characterization of risk a high priority in the chapters. Integrated teams that work together beginning at the technical input phase could bring in diverse perspectives, and guidance to the stakeholder workshops for each chapter would sharpen the messages about risk. He also suggested forming teams of research evaluators, including members of the research and practitioner communities, to build the authors’ understanding of ways to characterize risk. Another possibility is to have multiple author teams, which would be charged with working separately on vulnerability and impact, risk and uncertainty, and expert assessments. Garfin also suggested that risk-based analyses developed through the sustained climate assessment process could be used in the NCA4.2

Second, authors will need more time to do their work than they had for the NCA3, Garfin observed, as well as guidance on methods for evaluating the importance of a topic and characterizing vulnerability and risk in ways that are consistent, even if imperfect. This guidance should not just be a suggestion, he added, because consistency across the document is critical. The authors will need more research that provides risk-based assessments, particularly research that takes into account nonclimate factors to produce assessments of adaptive capacity.

Third, Garfin offered several possibilities for making sure the document meets the needs of those who will use it, including involving end users in the author teams and asking them to define the thresholds they use in making decisions. He recommended that models be used as a basis for discussion rather than for prediction. He advocated holding user workshops focused on risks and producing graphics and scenarios defined by users’ interests to help NCA

___________________

2 For more on this idea, Garfin referred participants to Buizer et al. (2015).

authors understand the specific challenges users face in addressing uncertainty and community values and thus help them in communicating about risk.

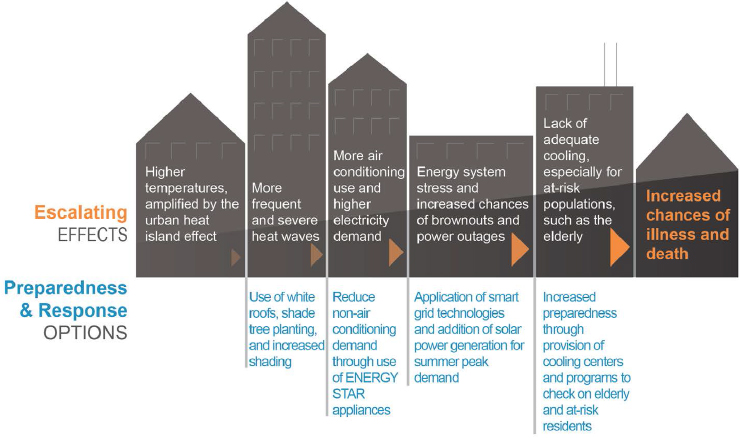

Garfin discussed a few communication strategies that he thought successfully addressed users’ needs. One was a graphic used in the NCA3, shown in Figure 3-1, which he said may have generated more positive feedback than any other graphic included in the NCA3’s Southwest chapter.

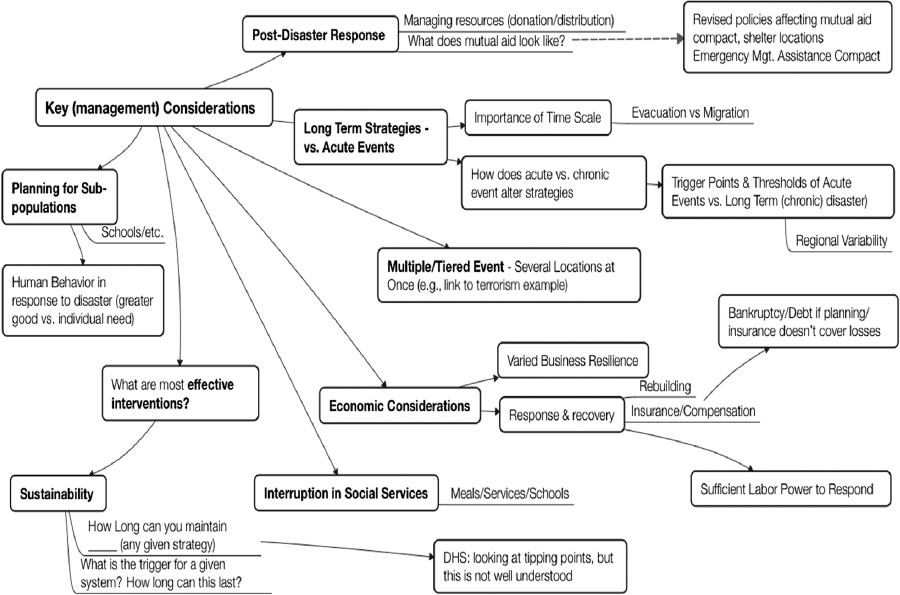

Another was a planning tool he developed with a colleague to guide the people of the Southwest in thinking about climate change impacts for their region, including drought, decreased reliability of the water supply, heat waves, increased energy demand, and strain on the power grid. The influence diagram in Figure 3-2 depicts connections among events and the responses of different stakeholders. A third strategy is scenario planning that guides people in conceptualizing the possible outcomes of different options.

Tools such as these cannot be used effectively at a regional scale, Garfin emphasized, but they are useful in case studies for localities. Another example he showed, a tool developed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, allows users to incorporate evidence about wildfire hazards in a region with expert judgment about the risks to high-value resource areas. The Forest Service surveyed users about their experiences using decision-support tools. Many of the users reported that the tools were useful, citing reasons such as the clarity and transparency they can bring to the decision process, help they

SOURCE: Garfin et al. (2014, Fig. 20.6).

SOURCE: Garfin et al. (2016, Fig. 3). Conceptual diagram (or “influence diagram”) showing potential cascades of impacts from the combination of drought, reduced water resources, and power outage in the Southwestern United States. Figure by Ben McMahan (University of Arizona) in Garfin et al. (2016).

provide in addressing conflict or controversy, and protection they can offer against litigation.

Overpeck suggested that “getting the risks right” will be a key issue for the Southwest chapter. He began with a description of the region, which is defined by the Colorado River Basin and includes seven states.3 This fast-growing region contains many large cities and many Native American nations and is also home to a significant volume of agricultural production. The Colorado River, which supplies the two largest reservoirs in the United States, is the primary water source for the entire region. Changes that affect the river’s flow will affect virtually everyone in the region, which has a population of between 30 and 50 million, Overpeck emphasized.

Recent projections for the river’s flow have conflicted, Overpeck noted. One recent report, from the Bureau of Reclamation, suggests that flow from snowpack runoff will remain approximately consistent through the 2070s. However, this report differs from a large body of research suggesting that river flows will decrease by 5 to 45 percent by mid-century. A look at recent data, Overpeck noted, shows a significant downward trend in flow over the past century, exacerbated by major droughts in the 1950s and the current drought, which began in the 2000s.

Drought can be caused by low precipitation, Overpeck noted, but the Colorado River Basin is experiencing a new type of drought, caused by warming temperatures. This is “a whole new ball game,” known as “hot” drought (meaning drought caused by global warming), Overpeck explained. “It’s going to get hotter” in the Colorado River Basin according to all models, he added. The only questions are how much it will warm and how decision makers should respond.

The risks projected by models are “worth betting on,” Overpeck suggested, when

- they are consistent with theory,

- they are consistent with ongoing change already observed,

- they are consistent across most models, and

- the physics of the projected change is consistent with both model results and observations.

All of these criteria hold true for model-based projections about warming in the region, Overpeck explained. Despite the Bureau of Reclamation report, he said, recent research he conducted with colleagues shows that warming alone will result in flow declines of 6.5 percent (± 3.5%) for each degree centigrade of average warming. The past 16 years of drought have resulted in an average 16 percent loss in flow, and they estimate that as much as 10 percent of that loss is the result of temperature increases. By mid-century, depending on emissions

___________________

3 The seven states are Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming.

levels, the median decline is expected to be 26 percent. The declines could be as high as 50 percent or more by the end of the century under the highest emissions scenarios.

The Bureau of Reclamation indicates that temperature increase will be offset by increases in precipitation, Overpeck noted. But, he said, models project a range of possible effects on precipitation in the region, again depending on emissions levels. The Colorado River Basin could get a little wetter or a little drier, or stay about the same. Given those findings, he suggested, placing a lot of hope in the possibility of precipitation increase seems unwise. The most recent report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) also found that there is substantial uncertainty in projections for storm tracks that could bring increased precipitation to the Southwest.

Moreover, said Overpeck, even if “you’re going to bet” that the mean precipitation levels will go up, “you also have to bet against the risk of multidecadal drought.” But estimates he and his colleagues developed, based on the paleo-climate record, project a 10 to 15 percent chance of a 35-year drought in the second half of the 21st century. In other words, even if average precipitation goes up, it is likely that the region will see multidecade periods when the Colorado River’s flow is below normal by 15 percent or more. The extreme end of the projection is that there may be temperature-driven reductions of 50 percent or more in the river’s flow.

The standard approach in the climate science community, Overpeck concluded, is to rely on averages across multiple models. To really give stakeholders what they need, in his view, it is necessary to take apart the components of the evidence base. A simple number can be quite misleading, and the stakeholders are well equipped to understand a more sophisticated analysis of the areas of uncertainty.

Udall turned the discussion beyond the Southwest to the broader risks to society. He cited a 2015 essay by Naomi Oreskes in which she chided the scientific community for being too scared of making a mistake.4 Though scientists are often accused of exaggerating the risk of climate change, Oreskes argued that they should be more emphatic. Scientists tend to be cautious in presenting their findings, the essay argued, which means they are too willing to risk Type 2, or “Trojan horse,” errors (missing a major risk) and too reluctant to risk Type 1, or “cry wolf,” errors.

Almost every week, Udall commented, new research is published showing “eye-opening climate risks.” Recent examples addressed increases in ice melting, sea-level rise, and superstorms; significant drying of the Southwest; and projections for multimillennial consequences of 21st-century policies. To illus-

___________________

4 This essay, “Playing Dumb on Climate Change,” appeared in The New York Times, January 3, 2015. Available: http://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/04/opinion/sunday/playing-dumb-on-climatechange.html?_r=0 [September 2016].

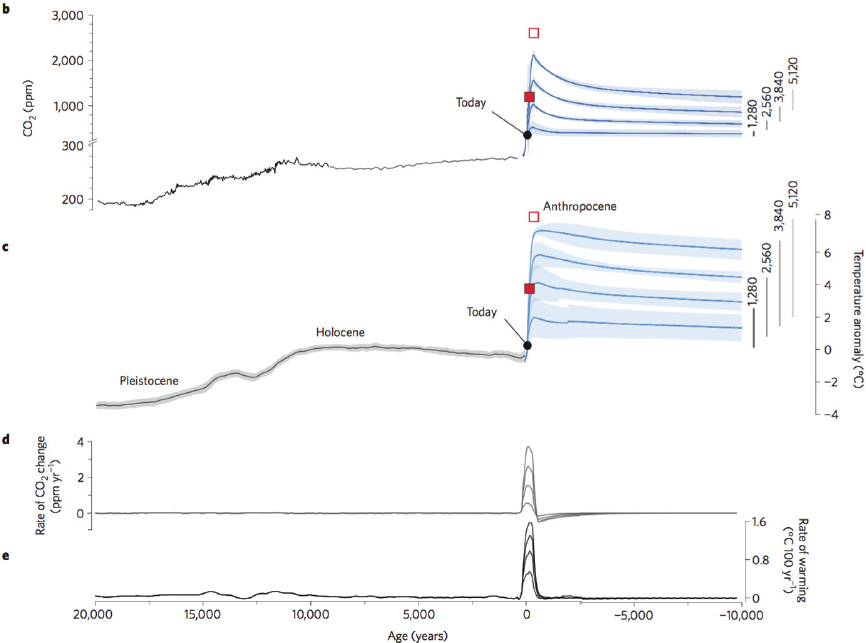

trate the growing awareness of long-term impacts, Udall showed graphs from a 2016 study, shown in Figure 3-3, which examined the effects of CO2 emissions on a 30,000-year scale. The top set of trend lines shows the persistence of CO2 in the atmosphere under a range of human-caused emission scenarios. The middle set of lines shows the effects of that CO2 on temperatures under the same range of scenarios, and the bottom set shows the rate at which CO2 levels will change depending on how quickly humans stop burning carbon. According to Udall, the study suggests the effects on temperatures are much longer lasting than changes in emissions or even changes in CO2 concentrations.

Looking at the NCA3 report, Udall noted all that was accomplished but also called attention to gaps that he believes should be addressed for the NCA4.

Framing of Risks. Risks in the sectors and regions were not adequately emphasized in the NCA3, Udall noted, but perhaps more important is that the report offers “next to nothing” about the unique nature of the existential risks to society. These risks are “really different from any kinds of risks humans have faced,” he pointed out, and the report did not get that level of seriousness across. The report generally frames risks on a 100-year timeframe, which in his view is too short. It is like “driving at 100 mph and providing information only on the next mile,” he noted. It is not the case that there is greater uncertainty associated with projections for all of the longer-term consequences, he added; indeed, “when people see the irreversibility, they wake up.” The design of the NCA3, which provided short, stand-alone chapters on each topic, made it very difficult to accurately frame the risks, Udall added. The authors were not given clear guidelines for handling risk consistently across topics or examples of effective ways to convey risk information.

Mitigation. The NCA3 says “next to nothing” about mitigation, Udall observed, noting that “we’ve been too skittish.” Scientists have been cautious about overstepping the line between describing their findings and conclusions and making recommendations, he said, but mitigation is “the most critical form of risk management we have.”

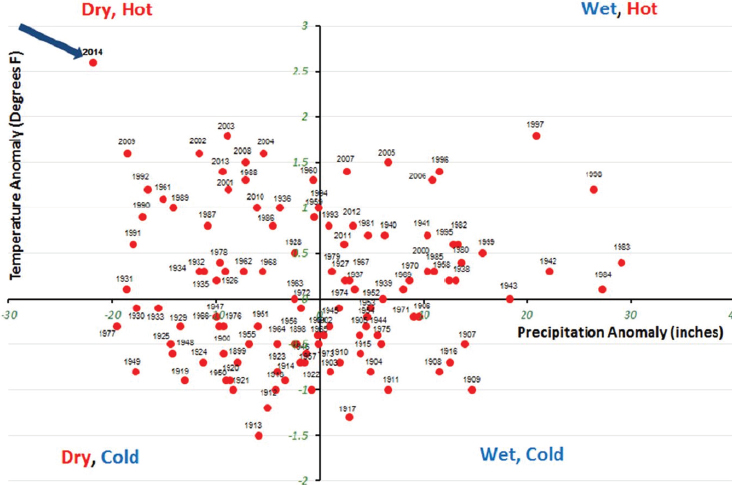

Return Periods (estimates of likelihood). Risk is often discussed in terms of how likely an event has been in the past, Udall noted, but “backward-looking return periods provide no useful guidance for the future.” Udall used a study of temperature and precipitation in California to illustrate how the trend for both has moved consistently in the drier and hotter direction. As Figure 3-4 shows, the years since 2000 (circled) were on average much drier and hotter than earlier years. In other words, the frequency of anomalous high heat and low precipitation periods has increased relative to the mean for the years 1901 to 2000. It is important to recognize that relying on data about past trends can lead to a false sense of security, Udall explained, but there are few useful metrics to replace comparisons with data from the past.

SOURCE: Clark et al. (2016, Fig. 1b-e). Reprinted by permission of Macmillan Publishers Ltd: [Nature Climate Change] Clark et al., Copyright © 2016.

SOURCE: Mann and Gleick (2015, Fig. 1).

Context. The NCA3 did not provide clear enough “anchors to help users understand the significance of temperature and precipitation changes,” Udall stated. Members of the public may compare daily temperatures and rates of precipitation with projections. For example, 10 percent might sound like a small change in temperature or precipitation, but its impacts would be very significant.

“We are playing dumb on climate change,” Udall concluded. The NCA3 did not portray the unique, irreversible nature of the risks. “Why isn’t it possible,” Udall wondered, “to say that burning carbon is risky?” It is critical to convey to people that continuing on the current path means “very large risks to civilization as we know it.” There are economically viable paths to a carbon-free world, but these must be pursued immediately and “with unparalleled vigor” to prevent dangerous changes to the climate, he argued. He closed with the thought that perhaps the most important challenge to climate scientists is to continue repeating these messages until they are heard.

The question-and-answer session allowed participants to highlight what they believed was most important for the development of the NCA4. With regard to characterizing risk, participants had several suggestions. One suggested identifying a set of variables to address in every chapter, such as effects on human health and forest health, biodiversity, and ecosystem services (such

as crop pollination, water supply, etc.). If these could be discussed in plain language, they would help “cut across” regional and sectoral differences and illustrate everyday consequences. Another suggested focusing on unprecedented events as a way of demonstrating the potential magnitude of the effects of changes that may sound small. Showing users how past shifts of only a few degrees in mean temperature have led to the development of ice sheets and their subsequent melting in a specific place, such as Ohio, can make the significance of changes occurring now more real. A third suggested that profiles of sets of scenarios, based on a range of assumptions that lead to alternate futures, provide a very useful way to portray risk and the range of possible outcomes.

Several participants emphasized the value of case studies that allow decision makers to focus on specifics and see how their own concerns can be addressed. However, others commented that identifying suitable case studies is very challenging and that it is important to use them strategically to highlight important ideas and to make clear why they are important. What has been missing is analysis from the social sciences that explicitly examines what different possible future scenarios will look like.

Several participants offered comments about the expertise authors should bring and ways to better weave in the perspectives of end users of the climate assessments. One noted that many scientists are uncomfortable with venturing beyond their specific areas of expertise and with offering their judgments about what should be done about their findings. Another noted that “there are no experts on climate change” because climate scientists tend to focus on their own relatively narrow areas. “No one is paying attention to big, cross-sector effects,” this person suggested. Using broader expert panels that include decision makers at different levels and including nonscientists on author teams are two ways these participants suggested to both bolster the scientists’ confidence in speaking beyond their areas of expertise and make sure that users’ practical concerns are carefully considered.

COASTAL REGIONS

Margaret Davidson of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Robin Gregory of the University of British Columbia, and independent consultant Susanne Moser offered their perspectives on how the NCA4 can best address coastal regions.

Davidson drew on her experience with the NCA3, noting that the assessment was the first to include a chapter focused explicitly on coastal issues. There are many challenges posed by rising sea levels and related changes, she noted, but she argued that the greatest is the need for changes in behavior “at a very fine scale.” The infrastructure located along the U.S. coastline is managed at a local and regional level, she noted. Decisions about planning and zoning that have critical long-term impacts are made at those levels.

The individuals who make these decisions, she added, bring different levels of experience and perspectives to their jobs. Regional water resource managers, she observed, tend to have a very sophisticated understanding of risk management, but the local officials who respond to flooding, for example, are less likely to think on a national scale or in long timeframes.

These observations highlight the importance of considering the needs of the audience in framing the coastal chapter of the NCA4. The NCA3 included regional assessments and local case studies, which in Davidson’s view were far more useful than the national assessments. The case studies in the NCA3 were arranged on a national map to make it easy for people to identify the ones most relevant to their own challenges.

Davidson also stressed the importance of using language that is accessible to audience groups. Within the climate science community, she noted, “we all kind of understand what we mean by risk and uncertainty, but most people don’t know or care.” The developers of the NCA3 coastal chapter brought together groups of experts that included policy makers as well as representatives from the segments of the coastal sector the authors hoped to address. These groups reviewed both the substance of the material the authors were developing for the chapter and also the ways they were shaping the presentation. Davidson noted that the case studies required a significant investment in Website maintenance and that the group meetings were expensive.

“We are sometimes dumb about how we frame and present important communication,” Davidson observed—and slow to learn. For decades, she noted, the National Weather Service reported storm surges in terms of the number of feet storm water rose above the high-water mark. “People don’t have time to search for what that means when a storm is approaching,” Davidson noted. Now surges are reported in terms of feet above ground level, which is “much easier to understand.”

The most urgent challenges in coastal regions will be to elevate and harden critical infrastructure and to relocate noncritical infrastructure, Davidson observed. This challenge will require innovative thinking about financing and other nonscientific issues, so technical input on these issues will be key to the usefulness of the NCA4 coastal chapter.

Gregory focused on strategies for addressing the many perspectives people bring to climate change-related issues. A stakeholder once told him, “science is interesting to people but it’s a very poor entry point into climate change issues.” What people are interested in, he added, is what will happen in their lives. Gregory used three projects he is currently working on to illustrate approaches for helping people make difficult choices that relate to climate change.

The first project involves safety issues for a bitumen pipeline. Gregory found that the experts involved were focused on such science issues as temperature, precipitation, sea-level rise, and storm surges. The residents in the

local community were focused on the salmon fishing industry and other impacts on their lives: their own jobs and place in society. It took structured dialogue, Gregory explained, to provide an opportunity for both sets of concerns to be expressed. The dialogue sparked community members’ interest in the relevance of information from scientific modeling and engaged the interest of industry and government representatives in the observations and concerns of local residents.

A second project, involving port security in a large city in the Northwest, presented a similar challenge. There, experts had tried hard to convince the personnel managing the port to consider planning for climate change impacts that are low probability but could have very serious consequences. The port officials were less worried, Gregory explained, about the possible consequences of those impacts than in the political consequences of the spending required to prepare for them. They were concerned that if the worst-case scenarios did not occur, they would be blamed for spending tax revenue to build in unnecessary protection. Dialogue was needed to help the two groups communicate their concerns, identify the objectives they shared, and identify responsive management alternatives.

The third project is an ongoing review of the possibility of listing the Pacific walrus, which is native to waters off the coast of Alaska, as an endangered species. This issue also has involved different perspectives among stakeholder groups. The science community—including engineers, biologists, and others—is focused on the factors influencing the growth and abundance of the species. Members of the local indigenous communities are more focused on how the walrus harvest might be affected if this species was listed as threatened or endangered because walrus hunting is both a vital tradition in the region and a critical source of food. Community members are concerned that an agency such as the Fish and Wildlife Service might place limits on hunting.

Gregory explained that in cases in which stakeholders hold different perspectives, a structured decision-making process can help people to set aside their positions and establish a common basis for dialogue by identifying objectives and considering new sources and types of information. Once the discussion gets going, he added, participants become very interested in others’ opinions and want to learn more about their knowledge and points of view. “People started to let perspectives they hadn’t considered in,” Gregory commented, and often their own views started to change in turn.

These conversations require time and skillful leadership, Gregory noted. It is very difficult to get people to think about issues that are upsetting and difficult, and climate change impacts are generally “dismal.” It is also difficult to get people to integrate diverse kinds of information and dimensions of values. “Experts are as prone to judgmental biases as members of the public,” he commented. This means that expert judgment elicitation, an element that many workshop presenters recommended for the NCA4, is both essential and quite challenging. It is important to be sure the group addresses key areas of uncer-

tainty. But identifying those and structuring precise questions for the group to address is just the start—the experts might still really disagree.

Effective dialogue and public communication about climate change issues is the responsibility of the climate science community and decision makers, Gregory added. “It is our job to make ourselves intelligible,” he said. This can be done by focusing on the concerns of the people who need to be reached and engaging them on their own terms.

Gregory had specific recommendations for the NCA4. With respect to the case studies, he recommended using very brief text boxes that highlight what is most important about each example—illustrating how it made a difference in mitigation or adaptation by changing people’s minds. The short text could include links to a much longer description and other resources, but it should not be just a “nifty example.” More generally, he recommended reviewing the objectives that guided the NCA3 and how they might differ from those for the NCA4. “Who do we want to reach? What do we want to convey?” he asked. “Will it be a presentation tool or a tool for engaging in dialogue?”

Moser began by noting that the coastal chapter in the NCA3 was a very good knowledge assessment that reflected well what was known when it was released. Despite its quality, however, she believes that “we should not repeat it unchanged.” The probability that sea levels will rise and have significant impacts is 1, she pointed out. The only questions are how quickly and how much the sea will rise. The United States has never overprepared for coastal disasters, and it is unlikely to overprepare for changes that are already certain to occur. She proposed an approach for the NCA4 that would more directly address this challenge.

The coastal chapter of the NCA3 provided a frame for thinking about climate change risks, following the guidance the authors were given on vulnerability framing and confidence assessment. It did not provide estimates of confidence. She explained that the author team for the coastal chapter began with the question “what keeps you up at night?” to identify which outcome most threatens the system. They considered climate variables, potential physical impacts, and probabilities in identifying scenarios and other factors that affect coastlines. Some systems are more sensitive because of other stresses and their relative capacity to respond to stress, she noted. The authors tried to work through all of these factors to assess overall vulnerability. The interdisciplinary team worked well in identifying the most important things that could happen, she explained.

However, they were not able to provide risk probabilities, and Moser argued that this is actually a good thing. Quantifying the risk of “wicked problems” is a “dead end,” she said. The state of the science on sea-level rise is such that it is extremely difficult to quantify defensible estimates of probabilities, she explained, and that is not likely to change soon. Moreover, it is impossible, she explained, to develop a national picture of all the outcomes

that matter across the United States in a way that is sensitive to context and also accounts for critical interacting factors. Thus, the characterization of risk is a subjective judgment at best. The risks of climate change are not like other problems society has faced, she stressed. They involve multiple, conflicting demands and do not lend themselves to simple, linear solutions. Furthermore, she believes that it is extremely unlikely that the NCA4—a government report that will be released by the administration of a new president—will be able to convey messages about risk so clearly that its audiences interpret them in the ways the authors intend.

The NCA4 should not be an effort to improve on what the NCA3 did, or simply “fail better,” she argued, but a chance to find a better approach. Projections regarding sea-level rise will remain conditional, she noted. There are no studies that effectively integrate even the most important of the factors that will affect outcomes. Most planners and members of the general public are not in a position to understand complex risk assessments. Political expediency will likely affect the reception of the NCA4, yet the difficulty of responding will become

exponentially greater moving forward because of the physical changes already in process.

“We are running out of time” to provide the information people need to make forward-looking adaptation decisions, she said. Instead of characterizing risk, she suggested, it would be better to characterize the possible responses and pathways that will be required in a difficult future or ways to make society more resilient. The starting point should be neither risks nor the decisions that need to be made, but the problems that will need to be solved, along with an assessment of how long decision makers have to solve them. The goal would be to give decision makers what they need to solve their problems. Moser provided a list of 10 steps for the approach she proposes: a process in which scientists, practitioner experts, and stakeholders are guided through a deliberative process that allows all to share their knowledge and identify the most workable pathways forward for different contexts (see Box 3-1).

In closing, Moser noted that even the most carefully prepared risk assessments and characterizations are not fit for the purposes of a national assess-

ment. The objective for the NCA4 should be to help policy makers focus on, prioritize, and assess problem-solving strategies for the challenges that are sure to come. Instead of simply communicating how bad the situation is, she argued, the NCA4 can change the public discourse into a problem-solving conversation about coastal risks and adaptation.

During the discussion period, participants focused on their reactions to the suggestions for the NCA4 put forward by the presenters. Some comments addressed practical ways to use the ideas; others speculated about their conceptual implications.

Several participants suggested ways that the sorts of processes described by Gregory and Moser could be used in the context of NCA4. The NCA already includes discussion of adaptation, mitigation, and decision support, one noted, and there is wide agreement that these are expected to be strengthened in the NCA4. Because the NCA4 is a national document, however, one noted, it would not be possible to build in the processes suggested for every sector and region. It would be possible to use a few case studies to demonstrate how it could be done and provide supports and resources that people could use to try these approaches in their own contexts. One noted that the ongoing, sustained assessment, as distinct from the reports produced every 2 years,5 could provide a mechanism for engagement and partnership, which could contribute both to the development of the NCA reports and to building capacity.

Several participants questioned the sharp distinction Moser had made between risk assessment and the focus on resilience preparation that she described. One noted that executing her 10 steps would require risk analysis as part of the process for identifying priorities. Another questioned whether many in the climate science community would oppose her approach on the grounds that it is “too alarmist” and that it may be too early to shift so much focus to adaptation. Communication about risks has been helping to move public discussion toward mitigation and has helped people to recognize that it is still possible to forestall the worst sea-level rise. On the other hand, several participants agreed that focusing not on the risk of climate change but on the risk of failing to deal with it could be very valuable in “shaking people loose.”

ENERGY-LAND-WATER INTERACTIONS

Peter Gleick of the Pacific Institute, Paul Fleming of Seattle Public Utilities, and Joseph Arvai of the University of Michigan offered their perspectives on risk characterization in the context of the nexus among water, energy, and land. The NCA3 described the nexus this way:

___________________

5 See http://nca2014.globalchange.gov/report/response-strategies/sustained-assessment [May 2016].

Energy production, land use, and water resources are linked in complex ways. Electric utilities and energy companies compete with farmers and ranchers for water rights in some parts of the country. Land-use planners need to consider the interactive impacts of strained water supplies on cities, agriculture, and ecological needs. Across the country, these intertwined sectors will witness increased stresses due to climate changes that are projected to reduce water quality and quantity in many regions and change heating and cooling electricity demand, among other impacts. (Melillo et al., 2014, p. 43)

Gleick offered both general and water- and energy-related recommendations for the NCA4. He began with the observation that the NCA has made great strides since the first report was published in 2000. He reminded the group that the NCA cannot do everything, given its charge and limited resources. He suggested that it should focus less on reducing the uncertainty of projections and more on reducing the risks of climate change. But, he added, social and political issues come into play when the goal is to reduce risk, and those are much harder for the NCA to integrate. If the focus is reducing risk, he added, it will be important to pay more attention to the events that have low probability but the highest potential consequences, as many presenters had suggested.

He also stressed the importance of being clear about “how we know what we know,” and also “the implications of what we know” for adaptation and mitigation. He recommended that the NCA4 be explicit about issues such as what makes a sector vulnerable to expected changes and how to compare the cost of mitigation and adaptation to the cost of doing nothing. In the United States and around the world, governments and the private sector are already spending a fair amount of money adapting to climate change, “whether we call it that or not,” he observed. There has been no accounting of which expenses are climate related and how much is being spent. These costs are not included in discussions about risks.

Turning to water, Gleick went on, there are many points to consider. Issues include the availability of water, water quality, and links to human health. Risk assessments that do not look across sectors will miss critical issues such as these, he pointed out. For example, it used to be uncommon to consider the links between water and energy systems, but it takes a tremendous amount of water to drive the energy system that society has chosen to build—and it also takes a tremendous amount of energy to deliver clean water.

It is very likely that climate change will require significant changes in the operation of the energy and water sectors, Gleick noted. For example, some reservoirs in California are operated based on hand-drawn rule curves that use data on past snowpack runoff: these are no longer a sound basis for planning because of the loss of snowpack, Gleick noted. “We’re not dealing with that,” he suggested. Similarly, because of uncertainty about the range of outcomes for coastal aquifers and waterways, necessary steps are not being taken. It would

help water managers and other planners, he added, if they had clear information about which water and energy issues are climate-sensitive and therefore require new thinking about what to anticipate.

Like other presenters, Gleick emphasized the importance of planning for high-impact outcomes of uncertain probability, such as ecosystem collapse, dam and reservoir failures, species die-off, and political disputes about water. People do not understand where the thresholds are, he noted, and equity and environmental justice issues also need attention.

Gleick acknowledged that the past NCAs may not have been as widely read as they should be. One important step to increase readership is to involve the groups most vulnerable to climate change in developing the report, both to learn more explicitly about what their needs are and also to reach broader communities through them. As examples, these groups include water utility managers, managers of highly energy-dependent operations, forest fire agency managers, reservoir and ski-resort managers, coastal regulatory planners, and infectious disease specialists.

Gleick’s closing point was that the NCA cannot accomplish every goal that people may have for it. Improved clarity on the role it should play and the primary audience it should address would help sharpen its focus. His opinion is that if it can make a strong case in identifying the next steps that society needs to take to address risks, it could do a better job at motivating government at all levels, professional societies, and the private sector to act.

Fleming focused on the framing of risk in the NCA3 water chapter. He noted that the document discussed the observed and projected physical changes in the water cycle in the context of systems and management responses. The chapter also addressed the cascading implications of those changes for resource management, adaptation, and institutional responses. The authors also discussed specific impacts of the physical changes. They considered variation by season and geographic region and looked at specific outcomes such as changes in soil moisture or snowpack. The authors did not, however, articulate a clear probability and risk framework for these issues. Fleming suggested that the scientific basis for doing that was not complete at the time so that developing such a framework would have been beyond the authors’ charge.

Looking forward to the NCA4, Fleming wondered whether risk characterization is “the end or the means” to other objectives. Acknowledging Gleick’s point that the NCA4’s primary purpose is to motivate people to take actions that increase resilience, he suggested that the focus should shift to risks that are most likely to do that. Public health threats, extreme weather, and economic costs are some of the issues that are “near to people in time and space” and most likely to move them to action, he noted. Issues such as these can be communicated to people in a qualitative way—the detailed risk and probability assessments that are difficult for some topics may not always be necessary, he suggested.

Fleming agreed with earlier speakers that identifying the audiences for the NCA is key because it cannot meet the needs of every possible user. He said he suspects, for example, that very few people have used the NCA for a specific vulnerability assessment because it is not detailed enough by region and sector. Seattle Public Utilities, he noted, commissions its own detailed vulnerability assessment. However, Fleming noted that he has used the NCA “as a buttress to support organizational changes” he advocated, such as a new management strategy for drainage and wastewater. The NCA text about new challenges and opportunities that cannot be addressed with existing practices, and the reasons why relying on historical data is no longer tenable, were extremely helpful to him in making the case for proposed changes.

Fleming also believes that the NCA4 presents an opportunity to establish new links between the report itself, which is a statutory obligation that comes with a specific charge, and the sustained assessment process that is just getting under way. The sustained assessment can be an incubator for innovation, particularly for some of the new ideas presented earlier in the workshop, and it should be “ramped up” and better supported, he suggested.

Decisions that are climate sensitive are being made daily, Fleming concluded, and they relate to essential services. Yet, he said, decision makers are to a large extent “flying blind” and “building for yesterday’s climate.” Advances that can be useful for these decisions are “eminently doable,” he added. Not all of the changes needed are expensive, he said, and that message can help users become more comfortable with building climate resilience into their planning.

Arvai also used a look back at the NCA3 as the basis for suggestions to the developers of the NCA4. The NCA3 was very effective in characterizing human use of energy, land, and water as an interactive system, he commented. This was an important contribution, in his view, but the next step is to move from what people need to know about this system to addressing what they need to know about how to manage the risks that will affect it. The focus in his view should not be on describing problems but on providing guidance for decision makers, from the part-time mayor of a coastal town to those making the large-scale decisions that affect complex systems and large numbers of people. “This is an opening that is begging to be filled” and could significantly increase the audience for the NCA4, he said.

Decision making, Arvai added, should no longer be framed as “doing something versus doing nothing.” This framing “sounds like an ultimatum, not a decision,” and most people respond negatively to ultimatums. Instead, he suggested, the report could guide users to think through the range of options available in managing the energy, land, and water systems.

The previous NCA reports, though available online, have been primarily text-based, he added. The next round, he pointed out, is an opportunity to make this resource far more interactive, which would be especially useful in addressing a dynamic, interactive system such as that of land, energy, and water.

If an online version allowed users to modify parameters to see how a system would respond over time to different impacts, under different assumptions and constraints, it could be far more useful to decision makers. Links to other work—such as the Marian Koshland Science Museum’s Earth Lab,6 which allows users to use information about climate risk and energy systems to make decisions and see their outcomes—would expand the possibilities. The NCA4 will need to do more than nudge people forward, Arvai said. The decisions its users will make will be extremely challenging and have potentially major impacts.

Another key objective for the NCA4, in Arvai’s view, would be to more directly address social inequities in the way the impacts of climate change will be experienced. Previous NCAs have addressed issues of vulnerability in a fairly abstract way, he noted, but populations who are already disadvantaged are likely to be disproportionately affected by many of the disruptions related to changes in climate. The recent problems with lead in the water of Flint, Michigan, though not climate related, illustrate how careless decision making can have dire consequences, he said. This issue also highlights the importance of integrating other systems into the decision-making framework, he added. Social and economic factors of many kinds will play a critical role in supporting decision makers, determining what decisions are made and how they are implemented, and shaping the way communities and the nation respond to climate changes.

Finally, Arvai concluded, the NCA4 clearly has a vital contribution to make, but obstacles may limit its impact. Political pressure, particularly under leadership that does not accept the science of climate change, could undermine it. Its development relies heavily on the work of volunteers who have many other commitments. There is a clear need, he concluded, to put the climate assessment program on a more secure and sustained footing.

Richard Moss offered some comments to begin the general discussion. He highlighted the vital importance of the interacting water, energy, and land systems, noting that changes in them can potentially affect numerous vital services and cause social disruption. Given the range of stakeholders and interests involved in these systems, he noted, the challenge of coordinating them is potentially daunting. It is difficult to imagine a set of institutions that could accomplish that, he suggested, so coordination may need to remain informal. However, decision making in this arena is “tremendously complicated” in his view, and it is very difficult for leaders, civil servants, and others to look beyond their own complex responsibilities to consider interactions beyond their sector.

The NCA3 provided what Moss described as “categorical decision-making examples” that illustrate the direct possible outcomes of some actions. The report also did weave in the potential effects of mitigation. However, he added,

___________________

6 See https://www.koshland-science-museum.org/ [May 2016].

there are many challenges in integrating data across agencies, which often use incompatible platforms or analytic tools. New modeling and analytic work will be needed to make it easier to look at problems that cross the land, water, and energy sectors. One approach he suggested is to begin with a decision-analytic approach: taking specific cases and identifying what is needed to model them. Another is to build sets of models that address different scales. A very high level of detail may be needed to examine regional or sectoral contexts closely, he suggested, whereas integrated assessment models could explore the greater complexity that comes into play on a larger scale.

The water, energy, and land systems offer an excellent opportunity to address the technical and other challenges of thinking through the effects of climate change on a complex, dynamic, and interactive system. It is important to remember, he concluded, that global climate changes ultimately all involve connections across sectors. The NCA4 is an opportunity to support civil servants and others who must operate in a political system and face big challenges in bringing scientific knowledge to bear on decision making.

General discussion focused on strategies for meeting the needs of NCA users. One participant noted that the purpose of the NCA has changed. It was originally designed to inform decision makers and the public about climate change risks, this person noted, but much progress has now been made in doing that. As the goal shifts to supporting people in responding to those risks, new writing teams and strategies are needed. Another noted that there is little evidence about how previous NCAs have been used and how users have responded to them, and recommended that mechanisms for collecting feedback be among the interactive features built into the NCA4.

A few participants offered examples and comments to illustrate some of the obstacles that may constrain users from changing standard practices in response to the messages in the NCA. In one case, a group of utilities in the Northwest was offered models for assessing their energy use and the likely results with specific changes designed to limit their emissions of greenhouse gases. Few took up the models, the participant noted, because the utilities have little institutional pressure to consider limiting emissions as an explicit goal. Had the other potential benefits of making the changes been highlighted and monetized, or other incentives such as taxes been integrated, he suggested, the utility managers might have found more leeway to respond. Another participant stressed the importance of using examples in the NCA4, but also the need to distill from them the most important elements that make them useful.

Several other participants stressed the value of the NCA4 for helping to foster a political environment in which facility operators and other decision makers see less risk in changing practices on the basis of new information about climate-related changes. People are likely to be blamed if they change a traditional protocol that has an unexpected result, one noted. Establishing

procedures for collective decision making, in which multiple stakeholders influence the choices and share in responsibility for the outcomes, is another way to support those making changes. Another participant observed that many of the changes designed to reduce emissions may have other valuable social benefits—related to human health and the economy, for example—and that highlighting those also fosters a safe environment for action.