4

Strategies for the Fourth National Climate Assessment

The closing sessions of the workshop offered an opportunity for wide-ranging discussion of how the fourth National Climate Assessment (NCA4) might best assess and convey the risks of climate change and meet the needs of users. Jeremy Martinich of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) discussed recent EPA work that has an explicit focus on the benefits of taking actions that reduce greenhouse gas emissions and that might serve as a model for achieving some of the goals for the NCA4. The floor was then opened for general discussion, and the workshop concluded with final thoughts from members of the committee, two users of the NCA, and the executive director of the U.S. Global Change Research Program (USGCRP).

AN EPA APPROACH TO ASSESSMENT OF RISKS AND BENEFITS

The EPA has a long history of analyzing the impacts of environmental damage and pollution and their costs, Martinich noted. In 2015, the agency released a report from its Climate Change Impacts and Risk Analysis Project (CIRA), Climate Change in the United States: Benefits of Global Action (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2015), which described the risks of inaction and the benefits, in terms of damages avoided, of global action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

The report drew on the work of multiple teams who developed models designed to estimate physical and economic impacts of climate change across multiple sectors, including human health, infrastructure, and water resources. It used a consistent set of data on socioeconomic variables, emissions, and climate

to quantify impacts. By doing so, Martinich suggested, the report provided a more integrated look at the benefits of climate action in the United States than other available assessments have.

Table 4-1 shows the sectors and impacts covered in the 2015 report. Martinich noted that many other important physical effects and economic damages associated with climate change were not included in the report, so its estimates cover only a portion of the total benefits of reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

The report makes a strong quantitative case for the benefits of both mitigation and adaptation, Martinich said, and he presented its key findings:

- Global action on climate change limits costly damages in the United States. Across sectors, global greenhouse gas mitigation is projected to prevent or substantially reduce adverse impacts in the United States in this century compared to a future without emission reductions.

- Global action on climate change reduces the frequency of extreme weather events and associated impacts. Global greenhouse gas reductions are projected to substantially reduce the frequency of extreme temperature and precipitation events by the end of the century.

- Global action now leads to greater benefits over time. For a majority of sectors, the benefits to the United States of greenhouse gas mitigation are projected to be even greater by the end of the century compared with the next few decades.

- Adaptation can reduce damages and overall costs in certain sectors. Though actions to prepare for climate change incur costs, they can be very effective in reducing certain impacts and will be necessary in addition to greenhouse gas mitigation.

- Impacts are not equally distributed. Some regions are more vulnerable than others and therefore will experience greater impacts.

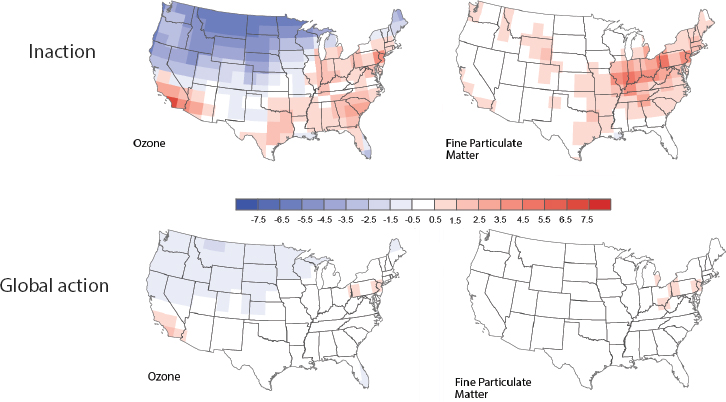

Martinich used the example of air quality to illustrate the kind of analysis the report provides for each sector covered. If traditional air pollutant emissions remain constant and no action is taken to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions, he explained, air quality is likely to worsen across much of the United States, particularly in the East, Midwest, and South. Densely populated areas are expected to be particularly affected by ozone levels. Figure 4-1 shows projections for ozone and fine particulate matter in the two top maps. The bottom two maps show the levels projected if greenhouse gas emissions are mitigated. The report describes some of the health benefits of the mitigation, including the prevention of 13,000 premature deaths annually by 2050 and 57,000 premature deaths by 2100. The economic benefits of preventing those premature deaths are estimated at $160 billion in 2050 and $930 billion in 2100.

Following that report, EPA is working on the next phase of the project

TABLE 4-1 Sectors and Impacts Covered in 2015 CIRA Report

| Health | Infrastructure | Electricity | Water Resources | Agriculture and Forestry | Ecosystems |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air Quality | Bridges | Electricity demand | Inland flooding | Crop and forest yields | Coral reefs |

| Extreme Temperature | Roads | Electricity supply | Drought | Market impacts | Shellfish |

| Labor | Urban drainage | Water supply and demand | Freshwater fish | ||

| Water Quality | Coastal property | Wildfire Carbon storage |

NOTE: CIRA, Climate Change Impacts and Risk Analysis Project.

SOURCE: Martinich (2016).

NOTES: Maps show estimated change in annual-average, ground-level hourly concentrations from 2000 to 2100. Numbers for the shaded bar indicate change in annual-average ground-level hourly ozone and fine particulate matter from 2000 to 2100 under two scenarios.

SOURCE: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (2015, pp. 24-25).

with an eye to providing analysis that will be useful for the NCA4, Martinich explained. The EPA is pilot-testing an approach for analyzing coordinated impacts. The sectoral models developed for the 2015 report will be used to conduct new simulations that can assess scenarios and climate projections being recommended for inclusion in the NCA4. A new technical report will document and describe the methods and results for each of the regions covered in the NCA4, he added. To do this, the new report will map the sectors to be included in the next version of CIRA to the sectors analyzed in the NCA.

CIRA is not the only project working on the challenge of impact analysis, Martinich noted. However, it does provide a source of recent, peer-reviewed estimates of risks avoided and economic damages that NCA4 authors can use. The next phase of CIRA work will test how the results of a coordinated impacts exercise using scenarios and projections could support further development of the NCA. In the longer term, Martinich hopes, the concept of a coordinated impacts modeling will become a credible and feasible way to incorporate analysis of avoided risk and the value of impacts into future NCAs.

KEY IDEAS FOR FUTURE ASSESSMENTS

The primary goal for the workshop, as moderator Richard Moss reminded the group, was to support the development of the NCA4, as well as future reports and the sustained assessment process, by identifying promising approaches for:

- characterizing the risks and clearly framing them in terms of their implications for people and systems,

- conveying clear and accurate information about those risks in ways that are useful and accessible, and

- identifying the connections across sectors and regions that are critical for understanding risks.

Moss offered his ideas about each of these goals to initiate a general discussion, and Joseph Arvai also offered a summary of key points he took away from the workshop as they related to the goals for the NCA4. Participants offered comments and questions that also highlighted the importance of ideas that came up during the workshop. This section summarizes the primary points from the discussion that were relevant to each of the three workshop goals. It closes with a synthesis of suggestions that individual workshop participants offered regarding the structure of the NCA4 and the process for developing it.

Characterizing Risks

A primary challenge in characterizing the risks of climate change, many participants noted, is to articulate the magnitude of the potential consequences. The scientific community, one noted, “excels at assessing probabilities but falls short on consequences.” Many participants commented that insufficient attention is paid to the tail ends of the distributions in climate models, which represent the scenarios that may be least likely to occur but have the most dire implications for humans. The likelihood of these most serious outcomes occurring cannot be determined precisely far in advance because they depend on choices people have yet to make and also on many interacting, cascading, and cumulative factors yet in the future. For this reason, climate scientists have been reluctant to focus on these “worst-case scenarios,” but these are the things that “keep people up at night,” many participants noted.

One key goal for the NCA4, numerous participants suggested, is to continue the effort to help people understand that climate change is a different kind of challenge for society and for risk assessment experts. This means, numerous participants argued, that it is time to help nonspecialists understand that it will not be possible to develop substantially greater confidence in estimates of the probability of these long-term outcomes. Hazards of serious

magnitude for which estimates of likelihood are uncertain are no less serious because of such uncertainty.

The importance of being clear about “how we know what we know” was raised several times. Some participants argued that people may ignore information about climate change because of confusion between outcomes that scientists agree are of great magnitude, although the probability that they will occur is low, and possible outcomes about which scientists have little knowledge. One participant suggested that it might make sense to develop a separate chapter that directly addresses the issues associated with assessing and communicating risk, rather than relying on a consistent presentation across chapters to convey the messages.

In that regard, several participants suggested that the focus of the NCA4 should shift from characterizing risks to supporting decision makers in addressing the risks productively so as to reduce vulnerability. Climate change is a “threat to national security,” a participant pointed out, citing the presentation by Alice Hill, yet “decisions are not being made on that basis.” Despite uncertainty about the likelihood of the most dire possible consequences, much is known about major changes to the Earth’s climate that will persist for millennia even if human beings stop emitting carbon today. Given that reality, several participants urged that the NCA4 communicate clearly about which changes are already inevitable and which can be precluded if human beings take action to mitigate the risks.

The worst unintended consequences for human life, participants pointed out, will result from mismatches in timescales. That is, the risk is greatest for those areas where the time remaining before it will be too late to mitigate a risk is far shorter than the timeframe within which the negative outcome will be apparent. It is critical to prioritize the risks that need attention based on careful consideration of timescales, a participant urged.

Several participants noted that in characterizing the risks of climate change, it is also important to be clear about what the risks mean for humans. People tend to understand and pay attention to risks that may affect them personally, and the NCA4 could be very useful in helping users to better understand the ways in which they are vulnerable to climate change. Marked inequities in vulnerability are already evident and are only likely to grow more extreme, several participants noted. It is important, in their view, that the NCA4 clearly articulate the particular risks to groups who lack the economic resources and political power to protect themselves. Reducing vulnerability is likely to be a more useful theme for the NCA4 than mitigating climate change processes because it is more concrete and immediate, several participants observed.

Conveying Risk Information

The way in which information about climate change risks could be conveyed in the NCA4 depends on the document’s goals and the nature of the audiences it is intended to reach, most participants agreed. In different ways, many participants suggested that the primary goal should be to get Americans to think seriously about how they can reduce their vulnerability to climate change by making decisions that help them adapt to changes already under way and help mitigate future changes. The challenge for the NCA4, one suggested, is to frame the risk in a way that is “empowering, not paralyzing.” “Many people don’t want to talk about this,” noted another person, and a key contribution for the NCA4 would be to help create an environment in which information about climate change is accepted and understood.

Much discussion focused on identifying possible audiences for the NCA4 and understanding their needs. Some participants suggested that the NCA can now move on from cataloging impacts and assessing the state of the scientific literature and can build on that base to address new kinds of users, such as officials and managers at many levels who need to understand the vulnerabilities of the sectors and regions in which they live and work in order to make sound decisions. The NCA4, many emphasized, should be designed to support its users, whether they are politicians, government officials from the local to the federal level, utility managers, engineers or architects, or other kinds of decision makers.

Numerous participants emphasized the importance of understanding how audience groups might use the NCA4. Many urged that the development process allow multiple ways for users to be engaged in identifying the questions with which they need help. Means of engaging stakeholders, including adding them to author teams, convening work sessions across regions, and involving them as reviewers and consultants, should all be considered, these participants suggested. Only by hearing from these groups will the NCA4 authors be able to provide information that is relevant in different sectors and across regions, some suggested.

Case studies were identified as a particularly valuable way to reach users by numerous participants. Specific cases make challenges vivid and allow users to work through specific sets of decisions and their implications. Most important, case studies are an ideal basis for helping users work through the application of the information the NCA4 provides to their own circumstances and challenges. A typology for selecting examples might help the authors use them consistently across chapters, one person suggested.

Many participants emphasized the importance of the NCA4 as a support for decision making and problem solving. Users can be guided in considering explicit tradeoffs, such as those between the demands of different sectors, between the goals of adaptation and mitigation, between budgetary priorities, and between the competing needs of different stakeholders. The NCA4 needs

to “find a way to structure the examples as good exemplars,” while making clear that they are not an exhaustive list and do not provide conclusive solutions, one noted.

No matter which case studies and other material are included in the NCA4, several participants noted, it cannot address the needs of every user or cover every important topic. One suggested that a key contribution would be to weave the perspectives of social science into the framing of ways to reduce vulnerability. Collateral benefits of actions intended to reduce greenhouse gas emissions—for human and environmental health and the economy in particular—are important for multiple reasons.

Identifying Connections across Sectors and Regions

Several participants emphasized that risks that involve multiple regions or sectors are particularly important. It is in cross-sector and cross-region issues that “you see the really wicked problems,” one participant commented, because multiple stakeholders are involved and because interacting and cascading effects are most evident.

It can be difficult to integrate information across sectors and regions, several noted. Multiple types of decisions are involved. The impacts of climate change manifest themselves differently depending on the geographic region, and the impacts affect sectors differently. Sectors and the government agencies that are concerned with them in many cases collect different kinds of data and use incompatible data systems. Multiple institutions are involved in cross-sector and cross-region challenges. Duplication of effort and unintentional negative consequences can easily occur, one participant observed.

Because multiple stakeholders are involved, several participants noted, these are the situations in which engagement is most critical. The NCA4 can be useful by helping to identify uniform metrics for calculating risk, a participant suggested, particularly nonmonetary metrics that are needed to assess many critical risks.

Participants also noted the importance of looking outside U.S. borders as the NCA4 authors collect case studies and best-practice information. Canada and Mexico share ecosystems and other resources with the United States and are stakeholders in many of the same climate-related challenges. Moreover, another noted, the United States is not necessarily the leader in innovation in many areas and much can be learned from international examples.

Suggestions for the NCA4

Participants offered several suggestions to the USGCRP focused primarily on ways to sustain the assessment process and to make the NCA4 as useful as possible.

A number of reasons for strengthening the sustained component of the NCA—which operates continuously while the reports are released every 4 years—were put forward. The developers of the NCA4 are being given a serious and difficult charge, several participants noted, and are being pressed to do it quickly and “on the cheap.” If the political environment should become less open to discussion of climate change, the mission of the NCA will become more difficult, another commented. Updated scientific information is continuously available and should be folded into the guidance to users to the extent possible.

Several participants recommended that the NCA be made much more interactive. The first three NCA reports consist primarily of text that could be printed, even if most people gain access to the reports through the USGCRP Website. Some suggested further augmenting the text in the future by expanding the Website to add more links to other resources, tools to support decision-making, case studies, and background research.

The sustained assessment process that supplements the printed documents, several participants noted, can also build user engagement and support cross-sectoral discussions. This process can support ongoing dialogue about the status of knowledge and the possibilities for action as they evolve. Expanding options to support individual users in their own decision making might also be easier in a web format, a participant suggested. In any case, he recommended that the NCA4 draw on the research literature regarding decision making to provide explicit guidance to users.

CLOSING THOUGHTS

The final workshop session featured comments from committee members Baruch Fischhoff and Chris Weaver and two users of the National Climate Assessments, Margaret Davidson of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and Paul Fleming of Seattle Public Utilities. These panelists were asked both to offer immediate suggestions for the NCA4 and to suggest longer-term objectives for the future of the NCA. The workshop closed with reflections from USGCRP Executive Director Michael Kuperberg on the workshop’s messages to the developers of the NCA4.

Fischhoff provided a social science perspective on the challenges of risk communication. Reports going back to the 1970s have described these challenges in the context of risks to the environment, Fischhoff noted. Table 4-2 lists some of those reports. For example, a 1975 report on nuclear reactor safety and a 1981 report comparing the risks of different methods of generating electricity both assessed risks and candidly addressed key challenges in communicating about risks. What these and other reports make clear, Fischhoff explained, is that risk analysis inevitably involves definitions of valued outcomes that reflect particular ethical or political interests. Such definitions should be controversial, he suggested, if their implications are not buried in analytic

TABLE 4-2 Reports Addressing Environmental Risks

| Year | Title | Author |

|---|---|---|

| 1975 | Reactor Safety Study: An Assessment of Accident Risks in U.S. Commercial Nuclear Power Plants | U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission |

| 1980 | Environmental and Societal Consequences of a Possible CO2-Induced Climate Change: A Research Agenda | R. Revell, E. Boulding, C.F. Cooper, L. Lave, S.H. Schneider, and S. Wittwer |

| 1981 | Assessing Environmental Risks of Energy | P.H. Gleick and J.P. Holdren |

| 1996 | Understanding Risk: Informing Decisions in a Democratic Society | National Research Council |

| 1999 | Toward Environmental Justice: Research, Education, and Health Policy Needs | Institute of Medicine |

| 2011 | Communicating Risks and Benefits: An Evidence-Based User’s Guide | B. Fischhoff, N.T. Brewer, and J.S. Downs (Eds.) |

| 2011 | Intelligence Analysis for Tomorrow: Advances from the Behavioral and Social Sciences | National Research Council |

| 2013 | The Science of Science Communication | B. Fischhoff and D.A. Scheufele |

| 2015 | The Realities of Risk-Cost-Benefit Analysis | B. Fischhoff |

SOURCE: Fischhoff (2016).

language. Identifying definitions of relevant values that are acceptable to all stakeholders, he added, requires open deliberation (Fischhoff, 2015).

Past reports have also clearly shown, Fischhoff continued, that climate science requires collaboration among disciplines. An early illustration of the benefits of collaboration was a project of the U.S. Department of Energy and the American Association for the Advancement of Science, which began in the 1970s to examine the possible consequences of a CO2-induced change in climate (American Association for the Advancement of Science, 1980). The project report addressed a very wide range of possible effects, with chapters on oceans, the less-managed (by humans) biosphere, and the managed biosphere, he noted. It also addressed social and institutional responses, as well as economic and geopolitical consequences. Few climate projects since have matched that one in terms of involvement of the social sciences, Fischhoff noted. He pointed out that text from that report could have been written today. It warned that the impacts of climate change will not be distributed uniformly, highlighting potential economic and social effects. The report noted—35 years

ago—that despite some uncertainties in predictions, corrective action is needed and that “because of the varied geophysical, biological, and societal effects that may result from CO2 buildup, the problem calls for an unprecedented interdisciplinary research effort” (American Association for the Advancement of Science, 1980, p. 6).

Communication is also addressed by many other early reports that drew on social science. For example, a 1999 Institute of Medicine report on environmental justice laid out principles to guide communication, Fischhoff noted:

- Improve the science base. More research is needed to identify and verify environmental etiologies of disease and to develop and validate improved research methods.

- Involve the affected populations. Citizens from the affected population in communities of concern should be actively recruited to participate in the design and execution of research.

- Communicate the findings to all stakeholders. Researchers should have open, two-way communication with communities of concern regarding the conduct and results of their research activities. (Institute of Medicine, 1999, p. 7)

Although these older reports identified issues that still require attention today, Fischhoff noted, progress has been made. The NCA reports are readable, accessible, easily available, and relevant. There is an increasing public demand for the evidence, he said, because the NCA has been committed to making it relevant to people’s immediate concerns. There are also some examples of collaborative work to point to, he added, that demonstrate mutual respect among disciplines.

Despite this progress, however, there are “threats to the enterprise” in Fischhoff’s view. One is that there is “still more supply than demand for” the work of the social, behavioral, and decision sciences in climate contexts. Although there has been an enormous growth in basic research in these fields that is applicable to climate change and risk, little of it has made its way into practice. He also said he worries that the supply of research from these fields is not secure—many of the social science researchers who focus on climate issues are not in departments dedicated to their own disciplines. Moreover, there is no secure pipeline for developing and supporting these researchers, he added. As a result, Fischhoff suggested, “there isn’t a cadre of people ready to make the ‘last-mile’ connections,” that is, to make clear the precise relevance of climate science findings to people’s lives and concerns. When these connections are not clear, climate change messages can be skewed by “misplaced precision or imprecision,” he added. In many cases detailed analysis is available for issues that may be less important than others for which such analysis has not been done. The importance of the issue should drive the analysis, he said.

Fischhoff closed with three suggestions for the future:

- Provide more pilot studies that model how to apply what has long been known by social scientists. People learn best from examples they can attempt to copy and adapt.

- Obtain a “seal of approval” for communications about climate change. For example, the seal might indicate that authors have clearly presented the state of the science and their best guesses at its implications.1

- Adopt a standard approach to characterizing risk at a high level for broad audiences. Detailed analysis may not necessarily follow this standard, but effective communication about complex issues could guide users in understanding what is most relevant and where key decisions lie.

Fischhoff noted that one way to structure such a communication was developed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2009). That model guides users in identifying factors relevant to product approval decisions: analysis of a condition, treatment options, benefits, risks, and risk management. For each factor, users were guided to identify evidence and uncertainties, and then their conclusions and reasons for them. The process does not dictate the decisions, Fischhoff emphasized, but helps users to structure their thinking about key factors, clearly distinguishing between scientific issues and other factors.

Davidson focused on practical approaches to getting around the political sensitivities that often surround discussion of climate change. There is little practical difference between disaster mitigation and climate change adaptation for issues that pose immediate threats, she noted, such as flood, drought, and wildfire. In cases where the timescales are not important because the threats are imminent, she explained, there is no need to talk about climate: the actions people need to take are the same no matter how the problem is framed. The disaster community, she added, has made progress in developing an integrated and systematic approach to measuring losses and damages associated with extreme events.

The NCA, she argued, should provide a framework for regional engagement and assessment that is relevant to the risks people face today. Involving stakeholders in the process will be important to framing the risks not only from a scientific perspective, but in terms of threats to people’s daily lives. A process that involves both experts and nonexperts, she noted, will shape what is measured and how, and “help people come to an understanding of risk and what they value.” Citizen science—research to which volunteer nonscientists contrib-

___________________

1 Fischhoff referred participants to Fischhoff, Brewer, and Downs (2011) for more about this point.

ute by collecting and reporting data—is an important, and underused, tool for building engagement with and understanding of risk, she added. Aquariums and science centers provide another avenue for engaging the public and could do much more in this area than they have, in her view.

Weaver began with the question, “What is the value of the NCA?” The NCA3, he suggested, was “somewhat uneasily perched between two goals.” One was to build public awareness that climate change is occurring and will have diverse effects that will touch everyone. The other was to provide meaningful guidance for decision making. He believes it was more effective at the first of these goals and that new thinking will be required to make the NCA4 more effective at the second. An NCA4 that is aimed at supporting decision making, he added, may also be an even stronger tool for raising public awareness of risk.

The NCA “can’t support every decision or be all things to all users,” he noted. Every context is unique and requires its own detailed analysis. He suggested some ways that a national document could address this challenge.

Weaver suggested that in the past the NCA has not been especially explicit about the sorts of decisions that need to be made in a particular context. The NCA4 could be designed to point the way toward the kinds of analysis that will be needed to support decisions. Given the wide range of decisions that could be relevant, Weaver suggested, the developers could begin by identifying which types of decisions and decision makers the report could best serve. The developers might also consider which decision-making frameworks to address, he added. For example, tools often used to support decision making, such as benefit-cost analysis, are based on underlying assumptions that may not hold for future climate change scenarios about which there is considerable uncertainty. It would also be useful for the NCA4 to identify which types of hazards to include, he added. The report might focus on either reversible or irreversible hazards, for example, or those for which a critical threshold is approaching.

Identifying the upper boundary of risk might be the most important task the NCA4 could undertake, Weaver suggested. Many of the presenters had pointed out that too little attention has been paid to the low-probability but highest-consequence scenarios, he noted. Identifying those scenarios and providing tools for thinking about how decisions made today can influence them is a critical responsibility for the NCA4 in his view. This responsibility points to the importance of including analyses of the consequences that come with those outcomes. For example, the report could assess the consequences of a particular worst-case scenario across a number of sectors and then explore the kinds of responses that could mitigate them. The organizing principle could be to systematically identify the specific questions to be asked in different sectors and regions about the implications of these scenarios and provide guidance about the kinds of detailed analysis needed to address them. One could think of this as a kind of “risk stress test,” he suggested.

Weaver concluded by observing that the process of constructing the NCAs has taught the community a lot. It is clear that making sure stakeholders are integrally involved is essential, particularly if the NCA4 is to focus on support for decision making. He said past experience also indicates that formal guidance to authors is much less useful than active facilitation, especially when the goal is to create a new kind of document. He also noted that consensus is not always essential in an NCA and that clarity about differences could be more useful than unanimity. Looking beyond the NCA4 to the future of the climate assessment program, Weaver suggested, the focus should be not only on assessing and characterizing risks, but also on “assessing our ability to respond to risks” and explicitly focusing on solutions.

Fleming began by noting that the NCA reports are not only required by statute, but also have been very valuable to federal agencies and other users. The sustained assessment just getting under way is technically not required but in his view is essential. While it is not yet clear what the sustained assessment will look like or what its scope will be, it should provide a venue for a greater degree of creativity than can be realized within confines of a report. These two components together—the sustained assessment and the 4-year reports—he suggested, will allow the NCA program to continue to meet the needs of those users who have long relied on it while also dramatically enhancing its relevance to new kinds of users. These paired platforms provide the opportunity to launch multiple ideas that may take different directions, he added.

Fleming endorsed the idea that the NCA4 should focus on responses and solutions. There are many examples of well-founded and robust approaches that the authors can draw on, and sustained engagement with multiple stakeholders and experts will help the report’s authors identify the most relevant and useful ones, he said. Case studies that make the “last-mile connections” mentioned by previous speaker Fischhoff, and that also illustrate how decision makers can respond, will be key, Fleming added.

A key contribution that this sort of report can make, in Fleming’s view, will be to help reveal the sensitivity of many sorts of decisions to climate issues. The political and cultural environment is still not uniformly favorable to conversation that includes climate change, and clear examples that highlight the implications of decisions can help to make that environment more open. “Many parties would welcome partnering on that,” Fleming concluded.

The workshop closed with Kuperberg’s reflections on the many ideas presented at the workshop and how the USGCRP might take advantage of them in strengthening the NCA program. Communicating about climate risk to a range of audiences will always be both important and challenging, he said, and it is a challenge that will need to be revisited repeatedly. He said he appreciated the advice and reflections of the workshop participants in support of what he views as a vital effort for the USGCRP.

Kuperberg began with a few broad points. He reminded the group of the language in the Global Change Research Act that describes the purpose of the Global Change Research Program, which is not only to provide scientific information, but also to assist the nation and world to understand, assess, predict, and respond to human-induced climate change. “The ‘assist’ part of the charge” is one that he and his colleagues take seriously, he stressed. The program’s work begins with fundamental research and ends with providing education and guidance, and he looks forward to “building the full range of that effort.”

Kuperberg also noted that he does not see the NCA reports and the sustained assessment process as in competition, in the way that some participants had suggested. The mechanisms for the sustained process are still new, he noted, but the USGCRP is “very much committed” to it. The NCA4 will be an important product of the sustained assessment process, he noted, but not an end goal—the primary goal is to build the capacity to continue on multiple fronts.

Kuperberg highlighted some of the points from the workshop that he said he hopes will influence the development of the NCA4:

- Characterizing and modeling cascading hazards and also dealing with the risks and uncertainties associated with them are challenging.

- Engaging authors from outside the traditional disciplines, including experts from the social sciences, will be key.

- Focusing on regional issues and needs is important. The developers of the NCA4 plan to work closely with the existing regional science organizations of the USGCRP member agencies because they provide strong bases of knowledge and experience. Kuperberg noted, though, that many issues overlap because a region might be defined and understood in various ways, such as by ecological or geological boundaries. Natural systems ignore geopolitical boundaries, Kuperberg commented, but decision makers must operate within them.

- Kuperberg suggested that the USGCRP might use a risk-based framework for identifying case studies that would be most useful, given that such studies could not be provided for every possible case. A storyline approach could make such information more inspiring and useful.

- Clear discussion of the timelines on which changes will occur and on which different sorts of responses can be accomplished and take effect will be very useful.

- The basic science is foundational. The USGCRP must keep advancing fundamental climate science and continue to feed it into the reports and other elements of the sustained assessment.

- Models are often tuned to the average condition, which could allow users to overlook some important features, such as low-probability but high-impact conditions (the tails of the distributions).

- The assessment program has practical limitations. One strategy for expanding the program’s reach is to work with institutions that have constituencies of their own and can help to transmit the findings from the NCA. The USGCRP is piloting public-private partnerships focused on resilience and preparation that can take advantage of existing relationships.

- Consensus is important, Kuperberg noted, but he also stressed the importance of characterizing the range of possibilities (e.g., the tails). This is part of helping users to understand probabilities and projections.

- There will always be room for improvement in communication, but Kuperberg said he took note of the challenge to reach out to new groups.

Kuperberg closed by noting that the U.S. government relies on the information provided by the NCA in making decisions and setting policies in many domains, for anything from the EPA’s Clean Power Plan2 to its Endangerment Finding,3 to setting guidelines for federal buildings managed by the General Services Administration. These decisions have far-reaching effects and can also provide examples that may be influential. He repeated his appreciation for the contributions of all the participants in this vital work.

___________________

2 See https://www.epa.gov/cleanpowerplan/clean-power-plan-existing-power-plants [June 2016].

3 See https://www3.epa.gov/climatechange/endangerment [June 2016].