3

Models of Care: National and International Perspectives

OVERVIEW

Moderated by Kim Robien, Session 2 panelists discussed several models of care in oncology nutrition from around the world. First, Rhone Levin focused on U.S. models of care, with one of the most common ways for cancer patients to access oncology nutrition services being via a hospital inpatient registered dietitian or nutritionist (RD/RDN). Given that inpatient dietitians are often assigned multiple floors and working on very tight schedules, “pulling” them to help with outpatient care creates what Levin described as a “very negative situation” for everyone involved—the dietitians, doctors, and patients. Other hospital-based models of care being implemented in the United States include referrals to outpatient dietitians, outpatient services with dedicated nutrition staff, and outpatient clinics with embedded nutritionists. Levin discussed the challenges associated with each of these models of care and several other, non-hospital-based models of care.

More generally, Levin also discussed the goals of oncology nutrition, with a major goal being to increase patients’ tolerance of their prescribed treatments; described evidence showing the value of nutrition services for oncology outpatients; and called for the need to develop what she called a “culture of nutrition” among all cancer care staff.

Liz Isenring shifted the focus of discussion to international models of care and described several different, mostly hospital-based care pathways being implemented in Australia, one example from Europe, and one example from Canada. She emphasized nutrition screening as a key component of any outpatient oncology nutrition care pathways. For her, a key message

from this workshop was the importance of evidence-based, validated nutrition screening tools. Such tools can be used not only to identify oncology patients at high risk who would benefit from nutrition treatment but also for monitoring. Isenring also emphasized the important role of evidence in the development of care pathways and stated that the first step to developing a model of care is to conduct a thorough literature search. “Being aware of the evidence is always the first step,” she said. But it is not the only step. The next step is collaborative critique of the evidence, with all stakeholders involved. Based on her experience, when the entire care team feels responsible for developing a care pathway, then the entire team is likely to ensure the pathway is implemented and that nutrition is on the agenda.

Following these two presentations, Diana Dyer provided a personal perspective on oncology nutrition care based on her experience as both a provider and a patient. This chapter summarizes both presentations, Dyer’s perspective, and the brief panel discussion that occurred after Dyer spoke.

MODELS OF NUTRITION CARE IN OUTPATIENT ONCOLOGY IN THE UNITED STATES AND BARRIERS TO ACHIEVING IDEAL CARE1

When she began her oncology practice, Rhone Levin recalled, a common paradigm was that malnutrition was an inevitable consequence of having cancer and going through cancer treatment. But based on evidence collected since then, such as that included in the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics’ (AND’s) Evidence Analysis Library (EAL), Levin said, “we know now that that is an outdated paradigm.” It is time to move past that way of thinking, in her opinion, and find what works for patients more effectively. That being the case, Levin said, “Malnutrition happens.” While it happens more frequently in certain diagnoses, notably gastrointestinal (GI) tract, pancreatic, and head and neck cancers, it also happens in patients with late stage diseases of other cancer diagnoses (Kubrak et al., 2010).

The Goals of Oncology Nutrition

Whereas mild and moderate nutritional deficiencies in cancer patients are potentially reversible, severe nutritional deficiencies are often not (Van Cutsem and Arends, 2005). Thus, malnutrition in cancer patients needs to be addressed before it progresses, Levin emphasized. The conversation needs to happen not just with oncology staff but also with patients. It is not uncommon, Levin observed, for an oncology dietitian to meet with a

___________________

1 This section summarizes information and opinions presented by Rhone Levin, M.Ed., RD, CSO, LD, Dell Children’s Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

patient who is new to oncology treatment and experiencing a decline in their nutritional status and who expresses to the physician what Levin said she could “almost describe as joy” that they are losing weight. Even many clinicians do not understand that weight loss in high-risk cancer patients can create an irreversible situation.

Malnourished patients may not be able to tolerate treatment, which means they may not be able to receive treatment. And while it may be difficult to stratify nutrition with respect to how it affects outcomes, including mortality from cancer treatment, it is easy to show that people who receive less treatment are less likely to be cured of their cancer or have their cancer controlled, according to Levin (Lammersfield et al., 2003; Fearon et al., 2006). In fact, any treatment hold or break potentially affects a patient’s ability to control or cure his or her cancer. According to Levin, some literature suggests that every day of treatment hold for head and neck cancer treatment decreases the effectiveness of the treatment by about 1 percent. So losing 1 week of treatment, for example, potentially decreases someone’s chance of cure or control by more than 5 percent. Given that many head and neck cancer patients start with only a 15 percent chance of cure or control, that loss is significant. With chemotherapy, guidelines suggest that patients need about 85 percent of their original prescribed dosages to achieve the best control. Thus, the overarching goal of oncology nutrition is to tolerate prescribed treatment, or, as Levin put it, “no break, no delays, no dose reductions.”

Levin identified several specific goals: early identification of pre-cachexia or cachexia states, early identification of involuntary weight loss, early identification of etiology-based malnutrition characteristics, and aggressive responses to nutrition impact symptoms to protect both quality of life and the treatment plan.

Data collected from the Cancer Nutrition Research Consortium on the incidence of nutrition impact symptoms in 2012 reveal a lengthy list of symptoms:

- fatigue (41 percent),

- constipation (33 percent),

- anorexia (31-80 percent),

- xerostomia (15-25 percent),

- nausea (26 percent),

- emesis (35 percent),

- gas/bloating (13 percent),

- reflux/indigestion (21 percent),

- early satiety (21 percent),

- diarrhea (14 percent),

- shortness of breath (17 percent),

- bothered by smells (48 percent),

- taste alteration (62 percent),

- mucositis (22-75 percent),

- dysphagia/swallowing (6 percent),

- dysphagia/chewing (3 percent),

- severe pain (7 percent), and

- decreased smell (6 percent).

Levin emphasized that not only do multiple symptoms often occur at the same time, but they also present in complex ways. One of the examples she likes to share with staff members who are training is that a natural instinct for managing diarrhea is to stop eating and to only drink clear liquids for a day or two, believing that decreasing stimulation to the GI tract will settle it down. But what do you do with a cancer patient who experiences 5 weeks of diarrhea? Managing these symptoms, she said, is “something beyond which a usual experience or a usual life experience would prepare you for.”

U.S. Recognition of the Role of Nutrition Services in Oncology Treatment

Several U.S. agencies recognize the role of nutrition in oncology treatment, including the the American Cancer Society (ACS), American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer, American Society of Clinical Oncology (limited to certain diagnoses and survivorship), American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, the AND, Association of Community of Cancer Centers, National Cancer Institute (NCI), National Comprehensive Cancer Network, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, and Oncology Nursing Society. However, while widely recognized as being an important part of treatment, the specific role of nutrition in treatment remains very ambiguous, Levin observed.

A key difference between the United States and several other countries is the lack of U.S. guidelines that either require or recommend a frequency of interaction with or even access to oncology nutrition services. Levin remarked that it is very much up to individual facilities to decide what and how often patients have access to dietitians.

Updated Evidence from the Field of Oncology Nutrition

Having served on the EAL oncology nutrition 2013 update group, Levin explained that the workgroup was instructed to answer or update only 11 of what had been around 80 to 90 questions or topics in the 2007 library. Being restricted to 11 questions created a flurry of discussion, with different opinions about how to prioritize the topics. They ended up

choosing their questions based on which information or evidence would best demonstrate the value of oncology nutrition service. The majority of evidence in the 2007 library was rated as Grade III (“limited number of studies”), compared to the majority of evidence in the 2013 library being rated as Grade I (“good—the evidence consists of results from studies of strong design for answering the question addressed”).

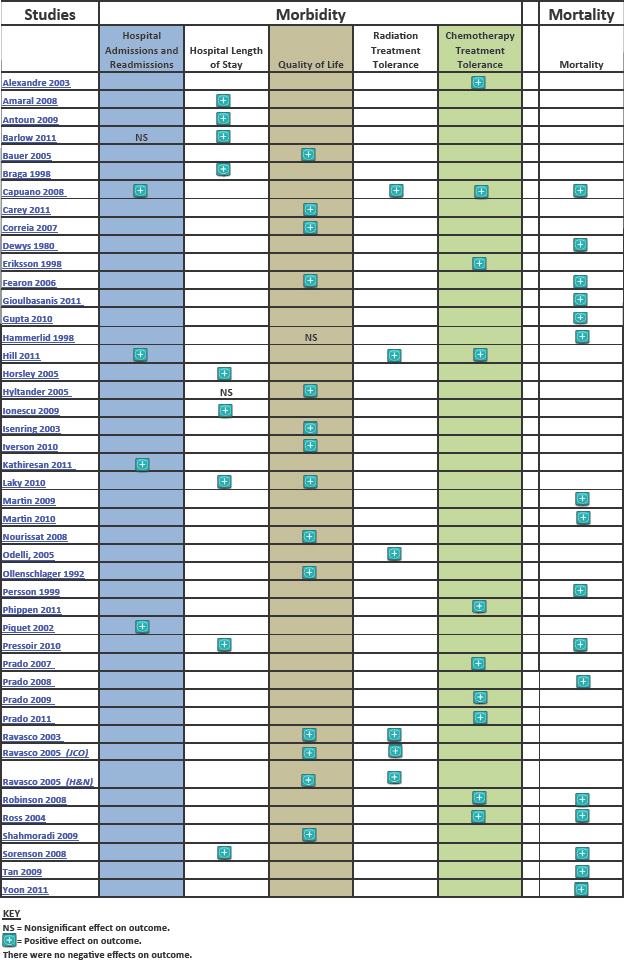

To help formulate their answers, the workforce put together a chart of nutrition outcomes data based on 45 studies demonstrating the effectiveness of medical nutrition therapy in reducing or preventing hospital admissions and readmissions, reducing hospital length of stay, improving quality of life, improving radiation treatment tolerance, improving chemotherapy treatment tolerance, and reducing mortality (see Figure 3-1). While the chart was created for use by the workgroup, Levin suggested that it might also be useful after this workshop to move the discussion forward with people outside the nutrition world.

Models of Care in the United States

One of the most common ways for cancer patients in the United States to access oncology nutrition services, Levin continued, is via a hospital inpatient RD/RDN who often is assigned multiple floors and working on a very tight schedule. Inpatient staff members are often “pulled” to cover outpatient oncology needs on an ad hoc basis, creating a negative cycle where the physician knows it is difficult to pull the dietitian and will therefore wait until they are sure they need one. But by that point, patients are often severely malnourished and in acute or crisis situations. Thus, a dietitian who is already short on time is faced with what Levin described as a “crash-and-burn consult,” which is not only time consuming for the dietitian but often not effective or not as effective as it would have been earlier in the process. From the patient perspective, again, severe malnutrition may be irreversible. In sum, Levin said, “The patient is losing, the facility is losing, the physician is losing, the dietitian is losing. It’s just a very negative situation.”

A second option is referral to a hospital-based outpatient registered dietitian. The challenge with this model, according to Levin, is that patients often see the outpatient dietitian only once. Moreover, most patients who see outpatient dietitians or nutritionists are self-selected patients with the ability to pay. Medicare does not cover oncology nutrition outpatient services, and many insurance plans either do not cover or only partially cover such services.

A third and “better” option, based on Levin’s experience, is for hospital outpatient oncology services to have a dedicated nutrition staff. The problem with this level of care, Levin explained, is that it is often limited

NOTE: H&N = head and neck; JCO = Journal of Clinical Oncology.

SOURCES: Mary Platek, March 14, 2016. © American Academy of Dietetics, Relationship Between Nutrition Status and Morbidity Outcomes and Mortality in Adult Oncology Patients. http://www.andeal.org/files/Docs/ON%20Nutrition%Status%20and%20Outcomes_%2007022013.pdf, copyright 2013, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Evidence Analysis Library. Accessed August 8, 2016.

to a certain day of the week, which means the nutritionist sees only those patients who come in on that day. Also, these services are limited in terms of the amount of time available to care for cancer patients. Levin mentioned a new dietitian recently assigned to an outpatient oncology clinic who reached out to the AND’s Oncology Nutrition Dietetic Practice Group (ONDPG) listserv, which has about 1,500 members, asking for advice on how to proceed and indicating in her email that she was “desperate.” That desperate feeling, Levin said, is a very common feeling among oncology dietitians—not just because you cannot see everyone, but because you cannot see everyone who needs to be seen. People who are turned away, she said, end up turning to the internet, their neighbor, or the health food store for relief.

The last and “best” hospital-based option, in Levin’s opinion, is to have nutrition staff embedded within the outpatient oncology clinic. But even in that situation, she said, there are no validated reliable benchmarking data regarding what constitutes an adequate full-time equivalent (FTE) for outpatient oncology nutrition. The recent National Hospital Oncology Benchmark Study found that 24 percent of the 58 infusion and 37 radiation facilities that responded to the questionnaire indicated they had nutritionists on staff. Still, it is unclear how many nutritionists are on staff at those facilities and whether the FTE numbers are adequate. At a facility where Levin used to work, the multidisciplinary care staff included an oncology dietitian. Funded by a National Comprehensive Cancer Control Program grant, the center saw what Levin described as “the most complex” patients. Based on a survey published in the Journal of Supportive Oncology, referrals to the clinic included nutrition-related diagnoses such as weight loss and nausea (Mancini, 2012). The most frequent interventions, exceeding all other interventions required, were nutrition interventions. For Levin, these data indicate that when a dietitian is present at the right time and in the right setting, nutrition interventions are the most frequent intervention required for patient care.

In addition to these various hospital-based models of care, there are a range of non-hospital-based models of care in the United States. These include specialty infusion companies that may have dietitians on staff who provide consultation for patients receiving tube feeding or total parenteral nutrition; and for-profit free-standing oncology centers that provide either radiation and/or chemotherapy but for which there are no standards regarding what is required or available for oncology care. A third non-hospital based model of care is the private practice registered dietitian or nutritionist. The question with this model of care, Levin pointed out, is whether these individuals have resources available to them, including patient information from the patient charts or from the centers where patients are receiving treatment. Lastly, many patients turn to alternative medicine providers.

Another U.S. model of care is nursing-based nutrition care. Given that nutrition is part of the scope of practice for nurses, it is appropriate for nurses to be able to handle and intervene in some of the early nutrition issues that come up for patients, Levin said. However, given that nurses are on a minute-by-minute, procedure-by-procedure schedule, they face many time constraints and tend to get drawn into focusing on medication management.

Other nutrition care venues available to patients include online resources provided by government, academic, and voluntary health organizations (e.g., ACS, NCI), which allow patients to treat themselves via links to symptom management materials. Often, Levin said, these are the only resources available to patients.

Finally, one of the newer models of care is what Levin called “fee-for-service.” The idea, she explained, is that through your smart phone you can “hire a dietitian in your pocket.” But this model of care raises questions about whether patients have the ability to pay out of pocket and whether smart phone technology can replace informed medical care. What is the credibility of these resources? Are they safe? Are they appropriate for complicated oncology patients?

Data on Nutrition Care for Cancer Patients

Colleen Gill at the University of Colorado conducted surveys of 56 NCI centers in 2011 and 2013 on dietitian FTE compared to patient numbers. Responding centers (28 in 2011, 23 in 2013) reported, on average, a little more than 3 fulltime dietitians per 5,000-6,000 patients. Clearly what happens in these situations, Levin said, is that only the very highest risk patients receive care.

In an online survey that Levin conducted with the ONDPG listserv, about half of the 177 clinics that responded reported using a validated malnutrition screening tool. Levin stated that use of such a tool is tremendously important, as it is what identifies the presence of malnutrition. It is unclear and a good follow-up question, in Levin’s opinion, to ask whether those clinics that use the tool are using it repeatedly throughout treatment. If the tool is applied the moment a patient walks into the clinic, before he or she has started treatment, there might not be any indication of malnutrition. But that doesn’t mean the patient will not be malnourished 1 week, 3 weeks, 6 weeks, or 32 weeks later. “We have to be repeating those processes,” Levin said.

In the same survey, when asked whether dietitians bill for their services, more than 80 percent of respondents reported they do not. Levin interpreted those results to mean “We are dependent on the good graces of the administration to hire and to staff the dietitians adequately.” When asked

to provide their opinions on whether their clinics have adequate oncology nutrition FTE to provide for their patient needs, the overwhelming response was “no.” When asked about perceived barriers to achieving ideal oncology nutrition care, most responses related to staffing, funding, and that dietitians are usually consulted only after malnutrition has already occurred. Levin remarked that these were the responses she was expecting. Still, it was interesting for her to hear from the ONDPG group.

One thing often reported in the literature, Levin observed, is that there are certified specialists in oncology nutrition “out there.” But typically when you use the “click here” link on a website “to find a board Certified Specialist in Oncology Nutrition,” most dietitians listed actually work at particular cancer treatment centers, and are not available to see patients outside those facilities. Thus, these links do not work for the thousands and thousands of patients receiving their care at one of the 75 percent of facilities without dietitians on staff, raising the question, how can access to board certified oncology dietitians be created? The answer, Levin suspected, will probably lead in the direction of requiring facilities to have some sort of specialist available. It is a question that needs to be addressed, she urged, because, without access, who is providing nutrition advice (a store clerk? the Internet?) and at what cost? Imagine you are a patient or the parent of an 8-year-old patient, she suggested, and you are desperate for information and you do not have access to a dietitian. So you go to the Internet. These are the kind of titles you will come across: “Reversing Cancer: A Journey from Cancer to Cure,” “The Cure of Advanced Cancer: A Summary of 30 Years of Clinical Experimentation,” “Nutritional Healing from Cancer: The Fundamentals of an Alkaline Diet,” “Take a Crash Course on ‘What Is Alternative Therapy?’,” “Alternative Cancer Therapies Available: Click Here,” “Read Stories of People Who Have Overcome Cancer,” “Choose an Alternative Doctor or Clinic: Click Here,” “Cure Cancer Now: Clear Out Negative Attitudes and Influences,” and “Fire Your Doctor: Health Truths.” This list, in Levin’s opinion, “ought to horrify just about most of you.” It is not just the out-of-pocket financial cost to the patients, Levin said, but potential reduced efficacy of cancer treatment (which is a huge expense), ultimately creating a burden to society because of a lack of patient access to evidence-based nutrition.

Beyond the basic nutrition care that is fundamental to healing among all cancer patients, Levin identified several areas of special interest where what she described as “mounting” evidence indicates that access to adequate oncology nutrition services would make a difference: nutrition in pediatric oncology treatment, nutrition for pediatric survivorship, nutrition for sarcopenic obesity and sarcopenic weight loss, nutrition for cachexia and pre-cachexia, nutrition for adult survivorship, nutrition for the preven-

tion of primary and secondary cancers, and oral chemotherapy medication interactions with food and nutrients (Prado et al., 2013).

Developing a Culture of Nutrition

In closing, Levin asked, what is an ideal situation for oncology nutrition care in the United States? She repeated the need to train and develop dedicated nutrition staff and emphasized the need to develop what she called a “culture of nutrition” among all cancer care staff, from physicians to radiation therapists, so that everyone is providing surveillance for malnutrition. She also emphasized the importance of using validated malnutrition screening tools on a routine basis in all cancer centers. Additionally, she called for all cancer centers to implement evidence-based medical nutrition therapy and provide ongoing monitoring and evaluation of patient success.

NUTRITION CARE FOR ONCOLOGY OUTPATIENTS: INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVE2

There are good data not just from the United States, but also from Australia, demonstrating that patients with cancer face significant nutritional challenges, Liz Isenring began. Data from the Australasian Nutrition Care Day Survey, a study involving 56 hospitals across Australia and New Zealand, found that, within the hospital setting and compared to other patient diagnostic groups, patients with cancer were 1.8 times more likely to be assessed as malnourished and to be eating less than 50 percent of offered food and 1.7 times more likely to have unplanned hospital admissions (Agarwal et al., 2012).

Unlike in the United States, a range of different evidence-based practice guidelines have been developed in Australia for the nutritional management of cancer patients, some of which Isenring remarked she has been lucky to have been involved in developing (Isenring et al., 2008, 2013; Brown et al., 2013). The first guidelines she was involved with were for cancer patients receiving radiation therapy because, this is where most of the evidence was (Isenring et al., 2008). Those guidelines have since been updated to include patients receiving chemotherapy, with a focus on patients with head and neck cancer, again because that is where most of the evidence is (Isenring et al., 2013). Isenring acknowledged the several other international evidence-based guidelines that have been developed by various enteral and parenteral nutrition societies (e.g., Arends et al., 2006; Weimann et al., 2006; August et al., 2009).

___________________

2 This section summarizes information and opinions presented by Liz Isenring, Ph.D., Bond University, Australia.

Developing Outpatient Models of Care: The Importance of Evidence and Collaboration

The development of oncology outpatient care pathways begins with a thorough literature search. “Being aware of the evidence,” Isenring said, “is always the first step.” The next step is collaborative development, which Isenring described as using a multidisciplinary team approach and involving all stakeholders in critiquing the evidence and coming up with an effective care plan. In her experience, she has found that when the whole team feels responsible for developing the care pathway, then the whole team is more likely to ensure that the pathway is being implemented and that nutrition is on the agenda. In addition to being based on the evidence and on collaborative development, care pathways should also promote consistency and reduce variation in practice. Once developed, care pathways also provide a baseline for data collection. A variety of oncology outpatient models of care exist, depending on the type of cancer, type of treatment (i.e., surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy), available health care services, and financial and insurance considerations. Isenring described examples from Australia, Europe, and Canada.

Outpatient Models of Care: Examples from Australia

The Australian Screen-IT model was developed for use with patients with head and neck cancer by Laurelie Wall and colleagues at the Princess Alexander Hospital in Brisbane. It was developed because, despite good evidence indicating that patients with head and neck cancer benefit from seeing a dietitian weekly throughout their treatment, anecdotal evidence suggested that, while weekly visits might be enough for a couple of weeks, many patients reach a “crash and burn” point when they would likely benefit from several visits per week. Meanwhile, other patients could actually go 2 weeks without nutritional treatment. Screen-IT provides a way to triage existing resources to where they would be of greatest benefit, with a focus on nutrition, swallowing, and distress outcomes. Isenring emphasized the multidisciplinary nature of this model of care, which is led by speech pathologists and dietitians but also involves oncologists, psychologists, counselors, and nurses. Additionally, in Isenring’s opinion, Screen-IT is a good example of not only being evidence based, but also taking that evidence one step further and allowing patients and caregivers to provide input themselves and highlight areas where they would like more support (see Box 3-1).

With Screen-IT, patients are provided an iPad when they come in to receive radiotherapy. On the iPad they are asked a series of questions assembled from a few different validated screening tools related to nutrition,

speech, and psychological distress. For example, they are asked whether they have experienced any taste changes or nutrition impact symptoms that have affected their ability to eat. They are also asked about texture and swallowing and, if the patient is tube feeding, how they have been managing. They are asked about their weight too, although Isenring expressed hope that weight will eventually become automated (i.e., the patient will be weighed when they arrive for their visit, and the weight automatically entered into the report). Other questions focus on a range of other topics, from acute changes the patient has experienced in just the past day to distress (i.e., patients are asked not only about any distress experienced during mealtime, but also distress related to family, finances, or anything else). The caregiver also has the opportunity to answer questions about distress.

After patients and caregivers answer the questions, an algorithm is used to flag patients at greatest risk and who need to be seen immediately, patients who have indicated they would like to discuss something in particular with a dietitian, and patients experiencing significant distress. Among those experiencing distress, guidelines are in place to determine whether or not the distress can be addressed in the joint speech pathology/dietetic clinic at the hospital (i.e., if the distress is related to eating), as opposed to the patient being referred to a counselor for ongoing psychological support (i.e., if the distress is related to other factors).

According to Isenring, at the time of this workshop, Wall and her colleagues were in the final stages of evaluating the effectiveness of Screen-IT. Isenring remarked that the tool has probably not increased the overall number of referrals, but that it has changed the pattern of referrals. That is, instead of all patients being seen once a week, some are being seen more frequently and others less frequently.

Another model of care being used in Australia, this one at Peter MacCallum, a cancer-specific hospital in Melbourne, similarly uses particular measures to identify high risk patients and determine how frequently patients should be seen (e.g., most head and neck cancer patients at high risk are seen weekly, followed by regular follow-up every couple of weeks,

but some are seen more frequently), whether they should be considered for tube feeding, and what other disciplines might need to be involved.

Yet another hospital-based model of care being implemented in Australia is a head and neck cancer pathway developed by Theresa Brown and colleagues at the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital. Again, a range of measures are used to identify risk and streamline decision making around the use of prophylactic percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) or tube feeding. It used to be, Isenring recalled, that this decision depended on clinician interest, with some clinicians being very pro-PEG while others viewed it as a last resort. This model of care represents a multidisciplinary effort to develop a more evidence-based and consistent decision-making process around the use of prophylactic PEG.

While hospitals in Australia generally provide good nutrition care in the hospital setting, Isenring observed, there is what she described as a “big gap” in post-hospital nutrition care. Outside of hospital settings, there are some specialist outpatient clinics in Australia, Isenring remarked, but waiting lists are long. There are also private practitioners, but their focus tends be on lifestyle modifications. Thus, their familiarity is with helping people to lose weight or manage their diabetes, and they may not have the resources to help patients manage complicated head and neck cancer cases. Additionally, something Isenring is starting to see at her facility, which is associated with a university, are specialists, often consultants from local hospitals, who come in to run clinics.

Outpatient Models of Care: An Example from Europe

From Europe, Isenring highlighted efforts by Hinke Kruizenga and the Dutch Malnutrition Steering Group to manage malnutrition in Dutch hospitals. The steering group developed 10 steps to managing nutrition treatment, two key ones being “quick and easy screening tools with treatment plan” and “screening as a mandatory quality indicator.” Dutch hospitals use a simple nutrition screening tool called SNAQ (Short Nutritional Assessment Questionnaire). Like the other screening tools Isenring described, this one helps with decision making to determine whether someone is high risk by asking a flowchart of questions.

In addition to addressing challenges around outpatient nutrition care, the Dutch Malnutrition Steering Group has also addressed what happens when patients finish cancer treatment. Not surprisingly, Isenring said, they found that one of the challenges is to find dietitians to whom patients can be referred. While patients are in the hospital, they have access to oncology dietitians. But after they are discharged, there are often questions around who has the expertise, the oncology dietitian from the hospital or a private practitioner; gaps in communication between dietitians; and other problems

related to discharge planning and handover from the medical team. Based on these findings, the steering group put together a toolkit with resources to help “up-skill” private practice dietitians in the community who see these complicated post-hospital cancer patient cases. Isenring mentioned that it is not necessary to know Dutch to use these tools. They can be accessed in English through www.fightmalnutrition.eu.

Outpatient Models of Care: An Example from Canada

As a final example of an outpatient model of care from outside the United States, Isenring described a multidisciplinary rehabilitation clinic for patients with cancer in Canada where the patient and family caregivers are at the center of the model and surrounding them is a multidisciplinary team with a dietitian, occupational therapist, oncologist, psychologist, social worker, nurse, and physiotherapist. The model was developed by Martin Chasen and colleagues as part of the Prostate Cancer Intervention Versus Observation Trial (PIVOT) study, an 8-week intensive program during which patients saw a physiotherapist for exercise treatment a couple times per week and nutrition impact symptoms were used to guide nutrition counseling sessions by the dietitian. A “whole battery” of outcome assessments were measured, according to Isenring. Not only did patients love the program and want to continue it, they also experienced what Isenring described as “impressive” improvements in nutrition, physical function, and quality of life (Gagnon et al., 2013).

Where to from Here?

Echoing earlier remarks by keynote speaker Steven Clinton, Isenring repeated that good evidence now exists and some guidelines too for certain groups of cancers, namely head and neck and GI (see Figure 3-2). “Let’s be aware of it,” she said. The challenge is implementing and translating that evidence into practice.

In summary, Isenring highlighted, first, that patients with cancer have significant nutritional issues, which affect not only the patient, but the caregiver too. Second, for the many cancers that are chronic conditions, nutrition requirements change over the continuum of care. Third, there are several sets of international evidence-based nutritional guidelines available that Isenring thought make for a good starting point for deciding what to do next. Fourth, there are several examples of models of care from around the world. Isenring praised the work being done by these various groups. Finally, just as all the anti-cancer treatments continue to evolve, so too should nutritional management of these same conditions. Isenring ended, “Nutrition is a fundamental right. It has to be there.”

SOURCE: Liz Isenring, March 14, 2016.

A PERSONAL PERSPECTIVE3

Diana Dyer was attending the workshop “wearing many hats,” she said, including as a childhood cancer survivor, survivor of two subsequent breast cancer diagnoses, and dietitian. She told the workshop audience how, at the end of her therapy for the second primary breast cancer diagnosis, she asked the oncologist, “What do I do now to help myself?” He looked at the floor for quite some time before looking up, meeting Dyer’s eyes, and saying, “Eat right and exercise.” She thought, “Wow, I’m on my own.” Even though she was a dietitian with 20 years of experience at the time, working in intensive care units and providing critical nutrition care support, she felt like a “patient floundering by herself in the trenches.” She made a call to

___________________

3 This section summarizes information and presented by Diana Dyer, M.S., RD, Consultant, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Cheryl Rock, who Dyer said “got me started,” but basically she was on her own. She had to “piece this together,” she said.

As she was piecing her care together, a medical journalist from the Detroit Free Press called Dyer for an interview for an upcoming story about “the race for the cure.” When the article ended up as a front page article, “overnight my life changed,” Dyer said. This was back in the pre-Internet 1990s. The newspaper article was printed in more than 60 newspapers. Dyer received more than 1,500 phone calls from people who had read the article and then found her number. People she spoke with said the information provided in the article had given them hope. But at the same time, they were angry that the information in the article was not being provided to them as part of their comprehensive cancer care. Immediately, Dyer started seeing patients in private practice. She was also asked to write a book, which is still in print and with proceeds being donated to the American Institute for Cancer Research (AICR) to fund research on nutrition and cancer survivorship. Dyer also started receiving invitations to speak at events around the country to raise awareness of the need for and benefit of nutrition for cancer survivorship, starting from the day of diagnosis onward.

Although her private practice eventually grew to where she had a months-long waiting list, with people flying from all over the country to see her, Dyer decided to leave her private practice after overhearing a comment by an oncologist at a meeting about how the cancer center where the oncologist worked did not have to do anything about nutrition because, the oncologist said, “We have Diana locally in private practice.” That was when Dyer realized that her private practice had been enabling cancer centers to not have dietitians on staff and that she had to do something on a much larger scale to break down the barriers to nutrition care for oncology outpatients. She said, “I don’t know what I’ve personally accomplished, but as a group, the fact that we are here today is an amazing step forward.”

“Cancer does not happen in a vacuum,” Dyer said. Food, she stated, is “the nexus” between prevention and treatment of chronic disease. She finds it painful that the public is fed by a food industry that pays no attention to health and treated by a health industry that pays no attention to food. Not only is it painful, but in her opinion, neither is it sustainable. The cost of cancer is astronomical, given the number of patients affected, with many patients already having other chronic diseases when they are diagnosed with cancer and with their increased risk as cancer patients for even more comorbidities. According to Dyer, 86 percent of U.S. health care costs are for chronic diseases.

Dyer emphasized that the role of food in cancer prevention and treatment is something “we know.” She said, “It is not a belief system.” Many foods or bioactive components of foods are known to decrease the activity of cancer stem cells. These include, for example, genistein, a component of

soy, and polyphenols in blueberries (Vanamala, 2015). “Food is not just food,” she stated. Dietitians are in the perfect role, in her opinion, to help patients understand which foods are going to be more effective, such as that half a purple potato has the same amount of cancer-fighting molecules as three and a half Yukon golds.

Dyer referred to the Hippocratic Oath (i.e., “first, do no harm”) and stated that it is the responsibility of the physician to order the right diet. The responsibility of dietitians, according to the motto of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, is “to benefit as many as possible.” Additionally, she referred to an African proverb: “If you want to travel fast, travel alone. If you want to travel far, travel together.” She said, “It’s time to travel together.” We have to move forward on this, she said, not just because it is the right thing to do, but because nutritional oncology solves problems. “We have the tools,” she said. They include everything from medical nutrition therapy to understanding how to sort through dietary supplements. Plus, registered dietitians can now attain board certification as a specialist in oncology nutrition (CSO).

Dyer noted the helpful role that gardening programs are beginning to serve in both survivorship and prevention programs. Based on her work at the farm at St. Joe’s Hospital (St. Joseph Mercy Hospital, Ann Arbor, Michigan) and the Harvest for Health gardening intervention study at the University of Alabama, Dyer said the message that “life begins the day one plants a garden” really resonates with cancer patients. Moreover, in her opinion, and referring to work by Wendell Berry, a farmer, poet, activist, and winner of the National Humanities Medal, for Dyer to be interested in food but not food production is “absurd.” In fact, the reason she and others started the farm at St. Joe’s, which is a certified organic farm, was not only to reduce potential carcinogens in foods consumed by cancer patients and survivors, but also to enhance intake of polyphenols (President’s Cancer Panel, 2010).

In closing, Dyer emphasized, “This is more than a call to action.” This is a call to reach what Dyer called a “big hairy audacious goal.” Implementation is critical to meeting such a goal.

PANEL DISCUSSION WITH SPEAKERS: DATA GAPS IN MODELS OF CARE

Following Dyer’s presentation, she, Robien, and Isenring participated in a brief panel discussion with the audience. This section summarizes that discussion.

Gaps in RD Care

Steven Clinton asked how different health care systems around the world incorporate or support RD care. Isenring replied that the Australian models of care she described during her presentation were being implemented in publicly funded hospitals and that publicly funded hospitals have higher FTEs of dietitians compared to private settings. That most costs of that care are provided by public funding may explain why Australia has what she considered “better” models of care. Australia’s Medicare scheme allows up to five visits per year for chronic conditions, including cancer, and according to Isenring, she and others were working with general practitioners to try to maximize nutrition care during some of these visits. In Australia, the gaps in care exist where the patient has to pay, which is where the challenge lies. Isenring agreed with Dyer that one goal should be to reach for the “big hairy audacious goal,” which she interpreted as examining the evidence and determining the best model of care. At the same time, however, Isenring urged also considering what is feasible and realistic and called for inclusion of more health economic outcomes in nutrition studies.

Physician Knowledge About Nutrition

An audience member remarked that physicians are often unable to answer patient questions about food and nutrition, such as whether tumors feed off sugar or gluten. Physicians often tell their patients to “just eat whatever you want” and that it is more important to stay well-nourished than to eat specific foods. She asked the panelists their opinions on gluten, sugars, and tumors. Rock replied that this workshop was not the appropriate arena for delving into those details. In Rock’s opinion, the questioner’s observation about physician knowledge of nutrition is a good example of why dietitians with specialty training in oncology are needed. “There’s so much confusion among health care providers,” she said.

Emergence of Medical Homes for Oncology Care

A webcast participant asked about the involvement of RDNs in the emergence of medical homes for oncology care (e.g., patient-centered medical homes). Clinton remarked that the medical home model has yet to reach Ohio, but the model warrants being studied and evidence-based recommendations being made (i.e., based on measured outcomes) for integrating food and nutrition.

Role of Telemedicine and Technology in Oncology Nutrition Care

The panelists were asked their opinions on how telemedicine and technology will likely affect oncology nutrition care in the future, not as a replacement for in-person care, but as a way to augment in-person care. In Clinton’s opinion, what the patient is doing is one of the most important pieces of information health care professionals need when counseling a patient in the outpatient setting. So any technology that provides that information, such as pictures of what the patient has been eating, has enormous potential to provide instant data on consumption. That way, when sitting down with a patient to council them on their dietary pattern, the counseling can be based on actual data, not a “guesstimate” based on a partially filled out food diary. That technology is advancing rapidly, he said, and “offers great potential.” Robien added that, as a researcher, she would advocate finding a way to somehow feed these collected data back into the evidence base.

Validated Nutrition Screening Tool for Pediatric Oncology

An audience member asked if there were any validated nutrition screening tools for use in pediatrics or guidelines to help identify patients with the greatest nutritional care needs. Isenring mentioned that an Australian group is in the final stage of validating a pediatric tool. Levin remarked that she recently took a position as a pediatric oncology dietitian and was surprised there was not more information. She added that this will be one of ONDPG’s next projects.

This page intentionally left blank.