4

Defining and Operationalizing Recovery from Substance Use

This chapter summarizes a presentation by Christine Grella (University of California, Los Angeles) on definitions of recovery from substance use and their implications for measurement and a presentation by Alexandre Laudet (Center for the Study of Addictions and Recovery, National Development and Research Institutes, director emeritus) on what is known from research studies about how recovery is viewed by those who are in recovery from substance use.

DEFINITIONS OF RECOVERY FROM SUBSTANCE USE AND IMPLICATIONS FOR MEASUREMENT

Grella said that although in the 19th century people with alcohol use problems were often “locked away” in institutions, that was also a time of growing awareness of the social problems that stem from alcohol misuse and of the subsequent rise of temperance movements. The concept of recovery from alcohol problems dates to the emergence of mutual self-help organizations within the context of these temperance movements.

Grella said that there were two wings of temperance movements, and these are echoed in the recovery movements that followed. The Washingtonian Temperance Society was a nonsectarian group with methods centered around public testimonials and a public temperance pledge. The idea was that recounting one’s past and affirming the present changed people’s identity, and this is echoed in later views of the role of self-definition and a public proclamation of being recovered. By contrast,

the evangelical temperance movement focused on gospel rescue missions, prayer meetings, and public proclamation of one’s sinful nature and transformation. The influence of this movement is also evident in some of the modern-day conceptualizations of recovery.

Alcoholics Anonymous was founded in 1935 and marked the beginning of a mass movement of mutual support groups for recovery. This movement also embodied the ritual of publicly proclaiming one’s identity as an addict or an alcoholic and the sharing of one’s stories from the past to illustrate the changes that have occurred in one’s life.

Grella discussed the Jellinek curve, which originated based on interviews conducted with members of Alcoholics Anonymous in the 1940s. The curve illustrates a process of moving into addiction that involves increasingly problematic behavior, “bottoming out,” and then a gradual recovery, with increasingly prosocial behaviors and engagement in recovery activities. Grella said that this model differs from contemporary views of recovery in a number of ways. For example, today there is more emphasis on intervening and averting a possible bottoming out. However, Grella noted that the model put forth the key concepts of trajectory, change, and stages.

Grella noted that telling one’s story continues to play an important role in the context of recovery. She used the example of the Faces and Voices of Recovery advocacy organization, which has a website where people can post their recovery stories. The International Quit & Recovery Registry is another website where recovery stories are posted. This latter website also serves as a platform for crowd-sourcing research on substance use recovery and a mechanism that provides an alternative to the clinical context for recruiting study participants. Grella said that studies on recovery tend to rely on clinical treatment samples, which means that they tend to have a higher representation of the relatively more severe cases. Alternative approaches that reach a wider group of people in recovery in the general population can help address this imbalance.

Grella said that there was an exponential increase over the past decade in the number of published scientific articles that have “recovery” or “recovered” in the title. The studies have used a variety of approaches to study recovery, including developmental or life-course approaches, clinical indicators, and behavioral indicators in clinical and cohort studies. Grella discussed these approaches in detail, along with two longitudinal studies that she worked on, along with the What Is Recovery? Study.

Developmental or Life-Course Approaches

The first approach discussed by Grella was the developmental or life-course approach to studying recovery from substance use. Studies of this

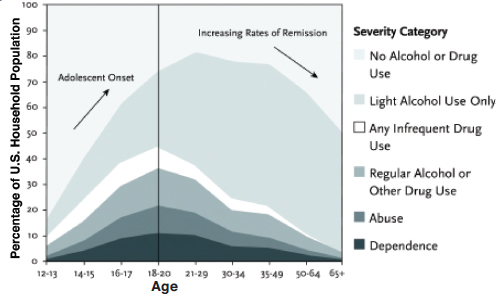

SOURCE: Dennis, M., and Scott, C.K. (2007). Managing addiction as a chronic condition. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, 4(1), 45-55. (Based on the 2001 National Survey on Drug Use and Health Data.)

type often use cross-sectional survey data to look at the percentage of the population across age groups that falls into different categories of severity in terms of substance use. The findings tend to show that the onset of substance use disorders increases over time through the adolescent period, reaches its peak in early adulthood around the ages of 18 to 20, and then gradually declines over time. Figure 4-1 illustrates this trend.

The questions of interest to researchers include the following: What accounts for this movement into remission over time? What are the drivers of change? What is the role of the maturation process? What is the role of life events that occur at different stages of the life cycle? Grella noted several constructs that are particularly relevant in this research: natural recovery, turning points, and recovery capital.1 Natural recovery refers to

___________________

1See Granfield, R., and Cloud, W. (2001). Social context and “natural recovery”: The role of social capital in the resolution of drug-associated problems. Substance Use and Misuse, 36, 1543-1570.

Laudet, A., and White, W. (2008). Recovery capital as prospective predictor of sustained recovery, life satisfaction, and stress among former polysubstance users. Substance Use & Misuse, 43, 27-54.

Teruya, C., and Hser, Y-I. (2010). Turning points in the life course: Current findings and future directions in drug use research. Current Drug Abuse Review, 3(3), 189-195.

Waldorf, D. (1983). Natural recovery from opiate addiction: Some social-psychological processes of untreated recovery. Journal of Drug Issues, 13, 237-280.

the finding that the majority of individuals who at some point meet the criteria for substance use disorders go into remission without any intervention. Turning points are life events, experiences, or role transitions (such as marriage, childbirth, employment, incarceration, and illness) that result in changes in the direction of pathways or persistent trajectories over the long term. Recovery capital refers to resources that individuals with substance use problems can use to cope with stressors and sustain recovery. This could include access to treatment services, 12-step groups, a supportive family, friends, and social networks.

Grella discussed an early study by Winick2 that was influential in framing how the field thinks about changes associated with the recovery process, and which coined the term “maturing out” of narcotic addiction. The research relied on Federal Bureau of Narcotics records of people addicted to narcotics, examining data for the period between 1955 and 1960 (N = 45,391), to determine what proportion were “inactive” at the end of the 5-year period, in 1960. Grella noted that using a 5-year period was common in other fields of medicine, such as cancer research, but in the context of recovery, there is a debate about the time period needed to reach a point after which the risk of relapse becomes significantly less likely. The study also had additional limitations pointed out by Grella, including its reliance solely on administrative records and that its lack of control for mortality.

Winick found that at the end of the 5-year period, 16 percent of the cases were inactive. The inactive cases ranged in age from 18 to 76, and the average age at the point of inactivity was around 35. The duration of addiction ranged from 5 to 56 years, with an average duration of 8.6 years. The research pointed at developmental processes, and the author argued that people in young adulthood may be more vulnerable to substance use because of the pressures associated with the transition into adult roles and responsibilities. As people get older, these pressures diminish. He also identified several factors that influenced cessation: external circumstances, relationships jeopardized by drug use, weariness, personality and insight, and incapacitating physical problems. Winick hypothesized that maturation out of addiction occurs as a reflection of a person’s life cycle and as a function of the length of the addiction.

Grella also described a study that reexamined the “maturing–out” hypothesis based on records and interviews with 248 opioid users who were treated at the Public Health Service Hospital in Fort Worth between 1964 and 1967 and followed up through 1975.3 The study concluded that

___________________

2Winick, C. (1962). Maturing out of narcotic addiction. Bulletin on Narcotics, 14(1), 1-7.

3Maddux, J.F., and Desmond, D.P. (1980). New light on the maturing out hypothesis in opioid dependence. UNODC-Bulletin on Narcotics, 1(002), 15-25.

there was little evidence of maturational change in terms of a therapeutic process and that external circumstances that propel people into recovery are more important. The authors identified five conditions that likely facilitated recovery among the population they studied: (1) relocation away from usual source of drugs, (2) evangelical religious participation, (3) employment with drug abuse treatment agency, (4) probation or parole for 1 year or more, and (5) alcohol substitution. Grella commented that polysubstance use complicates the conceptualization of recovery. Alcohol use in conjunction with other substance use is common among populations studied; in addition, Grella said, studies conducted today need to determine how to factor in marijuana use for medical reasons and whether such use violates “abstinence” among those in recovery from other substance use.

The study also looked at methadone maintenance, which, as Grella pointed out, raises the question of whether to integrate medication-assisted treatment in the definition of recovery. Traditionally, this factor was not included in the definition, but that approach is changing, and there is a need to better understand whether people who are in medication-assisted treatment think of themselves as being in recovery.

Another set of studies described by Grella was Vaillant’s longitudinal studies of male heroin addicts and alcoholics.4 His study samples included comparison groups and were followed over many decades. For example, the study of alcoholics included 268 Harvard undergraduates and 456 nondelinquent, socially disadvantaged Boston adolescents, and the participants were followed from age 20 to age 70-80. Vaillant also relied on records-based data and interviews with the participants. He found that at age 70, between 21-32 percent of surviving alcoholics were abstinent, and 11-12 percent were still abusing alcohol. Grella pointed out that findings of approximately one-third of the population in stable abstinence during follow-up appears to be common across studies. She noted that Vaillant’s study of heroin users also pointed at 3-5 years as the threshold that seemed to indicate stability, which the author called “freedom from relapse.” In the samples of both the alcoholics and heroin users, freedom from relapse was associated with community compulsory supervision; a substitute dependence; new relationships; and inspirational group membership, such as religion or Alcoholics Anonymous.

___________________

4Vaillant, G.E. (1966). A 12-year follow-up of New York addicts: IV. Some determinants and characteristics of abstinence. American Journal of Psychiatry, 123, 573-584.

Vaillant, G.E. (1988). What can long-term follow-up teach us about relapse and prevention of relapse in addiction? British Journal of Addiction, 83(10), 1147-1157.

Vaillant, G.E. (2003). A 60-year follow-up of alcoholic men. Addiction, 98(8), 1043-1051.

Vaillant, G.E., and Milofsky, E.S. (1982). Natural history of male alcoholism IV. Paths to recovery. Archives of General Psychiatry, 39(2), 127-133.

Stable “pre-morbid” adjustment, especially employment, was the most predictive of the outcomes.

Clinical Indicators of Recovery

The second approach to studying recovery from substance use disorder discussed by Grella focused on clinical indicators of recovery, particularly use of the clinical criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) to look at remission. Grella said that in the DSM-5 the criteria for remission from a substance use disorder are divided into two components: early remission and sustained remission. Among individuals with a lifetime substance use disorder, early remission is at least 3 but less than 12 months with no symptoms, except craving, and sustained remission is at least 12 months with no symptoms, except craving.

Grella began by discussing several studies that focused on clinical indicators of recovery using data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). She noted that the NESARC has excellent diagnostic data, and it is frequently used to study remission or recovery based on DSM criteria. The NESARC includes a baseline interview that collects in-depth information on lifetime history, including lifetime substance use disorders, onset, remission, and associated information. The NESARC also includes a 3-year longitudinal component. Grella pointed out that some of the questions are asked both retrospectively and prospectively, and the responses tend to differ, which presents a challenge for researchers.

One study conducted by Quintero and colleagues used baseline NESARC data retrospectively and looked at the probability of remission over the period of time anchored to the onset of dependence for four substances—nicotine, alcohol, cannabis, or cocaine.5 The study found that the probability of remission increases over time, most rapidly during the first 10 years following the onset of the dependence disorder. Grella noted that this finding is in line with the maturing out theory discussed earlier. Given that the onset of the disorders is often before a person’s early 20s, remission tends to happen in people’s mid-30s when adult roles and responsibilities come into play. Quintero and colleagues found more gradual slopes of remission for nicotine and alcohol than for cannabis and cocaine. Grella reminded workshop participants that many people who meet the criteria for a disorder go into remission without having sought treatment and without having interacted in a recovery context: thus, they

___________________

5Quintero, C.L., Hasin, D.S., de Los Cobos, J.P., Pines, A., Wang, S., Grant, B.F., and Blanco, C. (2010). Probability and predictors of remission from life-time nicotine, alcohol, cannabis, or cocaine dependence: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Addiction, 106, 657-669.

may not identify as being in recovery, even though they might meet the criteria based on their reported symptoms. This phenomenon represents a measurement challenge.

As discussed earlier, she noted, one conceptual challenge is related to deciding whether recovery requires strict abstinence or whether partial, nonproblematic substance use can be included. One study led by Dawson and her colleagues used NESARC data to look at this question by classifying respondents into categories of recovery based on the DSM criteria.6 Among those with lifetime alcohol use disorder, Dawson and colleagues created the following categories, according to past-year status:

- Still dependent: met three or more positive criteria for alcohol dependence.

- Partial remission: did not meet the criteria for alcohol dependence, but reported one or more symptoms of either alcohol abuse or dependence.

- Asymptomatic risk drinker: past-year risk drinker, but no symptoms of either abuse or dependence (for men, this meant drinking on average more than 14 drinks a week or drinking 5 or more drinks in a single day one or more times in the past year; for women, this meant drinking on average more than 7 drinks a week or drinking 4 or more drinks in a single day one or more times in the past year).

- Low-risk drinker: nonrisk drinker with no symptoms of either abuse or dependence

- Abstainer: did not consume any alcohol.

Asymptomatic risk drinkers, low-risk drinkers, and abstainers were classified as being in full remission. Low-risk drinkers and abstainers were classified as being in full remission and in recovery. The researchers compared the characteristics of the individuals in the two recovery categories—abstinent recovery and nonabstinent recovery—and Grella described some of the findings. For example, the study found that having a child under age 1 in the household was positively associated with abstinent recovery, but only marginally associated with nonabstinent recovery. Attending religious services weekly was positively associated with both abstinent and nonabstinent recovery. Seeking help that included 12-step participation was predictive of abstinent recovery, but not of nonabstinent recovery.

In another study, Dawson and colleagues used NESARC prospective

___________________

6Dawson, D.A., Stinson, F.S., Chou, P.S., Huang, B., and Ruan, W.J. (2005). Recovery from DSM-IV alcohol dependence: United States, 2001–2002. Addiction, 100, 281-292.

data to examine the age-related correlates of drinking cessation among regular drinkers.7 Some of the findings highlighted by Grella were the positive association between drinking cessation and the onset of liver disease among drinkers between the ages of 18-54, and the negative association between drinking cessation and higher socioeconomic status among drinkers over age 55. A college education (in comparison with a high school education) was negatively associated and smoking cessation was positively associated with drinking cessation among all age groups.

Another study described by Grella revisited the maturing–out theory using longitudinal NESARC data.8 Vergés and his colleagues analyzed data for individuals who in the follow-up wave met criteria for a drug use disorder in order to examine whether rates of persistence changed with age. They found that persistence is relatively stable across age. However, they observed a strong negative correlation between age and recurrence and between age and onset of a new disorder.

Behavioral Indicators of Recovery in Clinical and Cohort Studies

A third category of studies described by Grella focused on behavioral indicators of recovery from substance use disorder in clinical and cohort studies; these studies tended to focus in particular on abstinence and psychosocial functioning. One study of this type used a sample of patients treated for substance use disorder in a managed care system.9 Follow-up data were obtained from patients 1, 5, 7, and 9 years after intake. The study defined remission as abstinence in the past 30 days or nonproblematic substance use. Nonproblematic substance use was defined as drinking four or fewer times in the previous month; not having five or more drinks on any given day; not using marijuana more than once; not using any drug other than alcohol or marijuana; and not having suicidal ideation, violent behavior, or serious conflict with friends, family, or colleagues. Grella noted that the multicomponent definition used in this study goes beyond clinical criteria and attempts to integrate other measures of functioning.

A similar multicomponent approach used a latent factor that combines several individual indicators with shared variance was done by

___________________

7Dawson, D.A., Goldstein, R.B., and Grant, B.F. (2012). Prospective correlates of drinking cessation: Variation across the life-course. Addiction, 108, 712-722.

8Vergés, A., Jackson, K.M., Bucholz, K.K., Grant, J.D., Trull, T.J., Wood, P.K., and Sher, K.J. (2013). Refining the notion of maturing out: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. American Journal of Public Health, 103(12), e67-e73.

9Chi, F.W., Parthasarathy, S., Mertens, J.R., and Weisner, C.M. (2011). Continuing care and long-term substance use outcomes in managed care: Early evidence for a primary care-based model. Psychiatric Services, 62, 1194-2000.

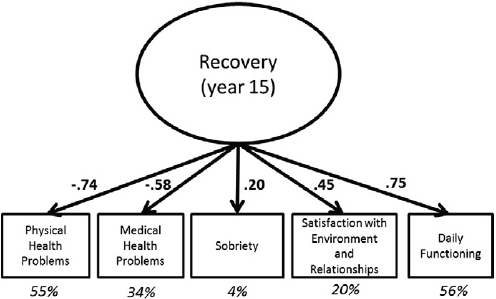

SOURCE: Garner, B.R., Scott, C.K., Dennis, M.L., and Funk. R.R. (2014). The relationship between recovery and health-related quality of life. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 47(4), 293-298.

Garner and colleagues, using data from the Pathways Study.10Figure 4-2 shows the different individual factors that co-vary into a latent variable of recovery, their correlation coefficients, and the percentage of variance explained by each variable that is combined in the latent construct.

Grella also discussed two longitudinal cohort studies that her group at the University of California at Los Angeles conducted. In one study, men with a history of heroin dependence who participated in the California Civil Addict Program between 1962 and 1964 were followed for more than 30 years, in three waves of interviews.11 The study defined stable recovery as 5 years of sustained abstinence from heroin. By the third follow-up wave (in 1996), approximately one-half of the sample members were deceased, and 22 percent could be described as in recovery.

___________________

10Garner, B.R., Scott, C.K., Dennis, M.L., and Funk, R.R. (2014). The relationship between recovery and health-related quality of life. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 47(4), 293-298.

11Hser, Y-I. (2007). Predicting long-term stable recovery from heroin addiction: Findings from a 33-year follow-up study. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 26, 51-60.

Hser, Y-I., Hoffman, V., Grella, C.E., and Anglin, M.D. (2001). A 33-year follow-up of narcotics addicts. Archives of General Psychiatry, 58, 503-508.

Hser, Y-I., Evans, L., Grella, C., Ling, W., and Anglin, M.D. (2015). Long-term course of opioid addiction. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 23(2), 76-89.

Another study that Grella was involved in followed a cohort sample of individuals who participated in methadone maintenance treatment in California in the late 1970s.12 This study was also longitudinal, and it used trajectory group analyses, which generated four clusters of individuals with similar patterns of heroin use over time: rapid decrease in use (25% of the sample), moderate decrease in use (15% of the sample), gradual decrease in use (35% of the sample), and no decrease in use (25% of the sample). The rapid decrease group averaged about 12 years to cessation of heroin use. Grella noted that this group had the highest rates of uptake of alcohol and other drug use after cessation of heroin use, which illustrates the challenge associated with the use of multiple substances in the context of defining recovery.

Grella also briefly discussed the What is Recovery? Study13 (which was earlier discussed by Keith Humphreys and Alexandre Laudet). Grella noted that the main difference in this study’s approach was the use of a sample that did not originate from a clinical setting, but rather from the general population, using an Internet recruiting method. The study’s goal was to identify the domains and specific elements of recovery as experienced by people who defined themselves in various ways in relation to “recovery.” Among the participants, 75 percent identified themselves as in recovery, 13 percent as recovered, 3 percent as in medication-assisted recovery, and 9 percent as having previously—but not currently—had a problem with alcohol and drugs. Grella noted the very small percentage of people who described themselves as in medication-assisted recovery, underscoring again that the views on this issue have not yet crystallized.

The study participants were asked to rate 47 items based on the extent to which they belong in a definition of recovery as they have experienced it. Factor analyses were then used to statistically reduce and group the 35 elements into four factors—abstinence, spirituality, essentials of recovery, and enhanced recovery. Latent class analysis derived five groups based on their adherence to items in each of the four factors: 12-step traditionalists (53%), 12-step enthusiasts (22%), secular class (11%), self-reliant class (11%), and atypical class (4%).14

Grella described the 12-step traditionalists as strongly abstinence oriented, with the majority indicating no use of alcohol or nonprescribed

___________________

12Grella, C.E., and Lovinger, K. (2011). 30-year trajectories of heroin and other drug use among men and women sampled from methadone treatment in California. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 118, 251-258.

13Kaskutas, L.A., Borkman, T.J., Laudet, A., Ritter, L.A., Witbrodt, J., Subbaraman, M.S., Stunz, A., and Bond, J. (2014). Elements that define recovery: The experiential perspective. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 75, 999-1010.

14Witbrodt, J., Kaskutas, L.A., and Grella, C.E. (2015). How do recovery definitions distinguish recovering individuals? Five typologies. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 148, 109-117.

drugs. They had high rates of treatment participation, particularly in 12-step programs, and strongly endorsed spirituality; they tended to identify as in recovery. The 12-step enthusiasts mainly differed from the 12-step traditionalists by being less likely to indicate no use of nonprescribed drugs. The self-reliant class moderately endorsed abstinence from alcohol and illicit drugs and no abuse of prescription drugs. They had lower endorsements of items on the questionnaire pertaining to social interactions, which receive particular emphasis in 12-step programs, such as learning how to get support, helping others, giving back, and being able to have relationships. Those in the secular class were generally younger, had spent fewer years in recovery, and more often identified as “used to have a problem.” They had lower levels of endorsement of spirituality and were more tolerant of nonabstinence, with higher rates of alcohol use. They also had lower rates of 12-step participation. Grella noted that although this group was small (11% of the sample), they are an important group to pay attention to because they are younger and may be tapping into changing social trends, including changing definitions of recovery, and the fact that recovery options are more diversified than they used to be. Finally, the atypical class, the smallest group in this analysis, was characterized by less endorsement of spirituality and abstinence and high intolerance for recovery being religious in nature. They strongly endorsed being able to enjoy life as fundamental to recovery.

In summary, Grella highlighted several considerations that emerge from the studies she described as important when deciding on a strategy for how to measure recovery from substance use. Recovery is both a process of change and a point-in-time status, which presents a measurement challenge. Longitudinal and cross-sectional designs can produce very different findings. The sampling frame deserves careful consideration, she noted, with the two main options being clinical samples and general population samples. There are some questions surrounding the criteria used for recovery: abstinence is the critical component in some studies, while others use a multicomponent measure. Grella pointed out that tolerating some non-abstinence and some looser definitions appears to be resonating with some study participants. Another important question is the role of an individual’s own perspective on recovery. Many studies measure behavior and outcomes that a person may or may not identify with as the status that researchers are attempting to understand.

Wilson Compton (National Institutes of Health) noted that one difference that seems clear in considering recovery from substance use disorders and recovery from mental health disorders is that in the case of substance use it is possible to specify the date when one stopped using a drug or drinking alcohol. In contrast, mental illness symptoms tend to wax and wane, and it is not easy to think about the initiation of recovery.

The question is whether it is possible to reconcile these differences to develop a unified approach or whether different measures are needed for substance use and mental disorders.

Steven Fry (SAMHSA) commented that it is important to keep in mind that in many cases substance use disorder and mental illness are co-occurring. He said that when he was hospitalized due to schizophrenia as an adolescent, he was introduced to the effects of chemicals on one’s emotions. After he left the hospital and visited his brother in college, he found other chemicals and substances and began drinking. This ended when he became a father, but he said that co-occurrence is not uncommon.

Donna Hillman (SAMHSA) added that in addition to the issue of co-occurrence, it is important to remember that there are many commonalities between the process of recovery from substance use and mental disorders. There are similarities in the reduction of substance use and symptoms, and there are basic tenets that need to be present to support the recovery process in both cases.

Nora Cate Schaeffer (University of Wisconsin) asked whether the identity of being in recovery is applicable in the same way to recovery from mental illness disorders as it is to recovery from substance use. From a sociological perspective, adopting an identity requires the availability of certain kinds of social supports or social structures.

Mark Salzer (Temple University) commented that people in recovery are a heterogeneous group, with some actively engaged in the mental health system and some not engaged, some who identify with being in recovery or the recovery movement, some who identify with a “peer movement,” and some who do not identify with any of these. There are also many overlaps in identities and the terminology that people use, which creates an interesting measurement challenge. He added that he was struck by the many similarities between the two related areas of recovery. In his experience working with people in recovery from mental disorders, they often talk about an event, change, or epiphany that took place in their lives that they consider the beginning of their recovery. This can be the case even if they continue to experience mental health issues or are hospitalized again: in some sense they think about being in recovery the same way as those recovering from substance use disorders.

Graham Kalton (Westat) said that, from a measurement perspective, he finds it difficult to reconcile the point-in-time perspectives on recovery with the idea of recovery as a process. In addition, it appears that there are different views on remission and occasional use of drugs or alcohol. He also wondered whether there are any methodological concerns related to the approach that involves asking people if they consider themselves to be in recovery because of the potential cultural differences in how this is viewed by different groups.

Grella clarified that in the NESARC, asymptomatic risk drinkers are described as in remission because they did not meet criteria for abuse or dependence, but they were showing problematic use. She added that the characteristics of this category are fairly technical. However, there was also discussion of abstinent versus nonabstinent recovery, which she agreed would require further study. She said that this is not typically the focus of dialogue in substance use recovery. The dialogue is more frequently centered around the extent to which abstinence is a defining criterion. For example, how to characterize someone who is participating in a 12-step group meeting and not using heroin anymore but is smoking marijuana occasionally or drinking alcohol?

Kim Mueser (Boston University) wondered whether the issue is that abstinence is how recovery is defined by those who are the strongest advocates of the concept of recovery. In other words, such organizations as Alcoholics Anonymous have been the strongest champions of the term recovery and their position is that there is no recovery without abstinence. Consequently, people who decrease their substance use or stop using in a way that presents a problem tend to not describe themselves as in recovery because that would not be in line with the view of Alcoholics Anonymous. In his view, Mueser said, some level of substance use that does not meet criteria should not necessarily present a problem in the context of the definition. Similarly, in the area of mental health, one could argue that, to some extent, symptoms of mental disorder are a part of normal human experience and that they have become over-pathologized.

Michael Dennis (Chestnut Health Systems) noted that from a clinical perspective, the DSM defines what level of symptom severity and duration meet criteria that define a condition. Remission means the absence of those symptoms for a period of time, and full remission means the absence of all symptoms. Under the DSM definition, addiction is not based on the amount or frequency of use, but rather the behavioral health consequences of that use. He argued that the reason there is a disconnect is because one part of the field focuses on substance use and the other part focuses on the clinical criteria for the disorder: there is overlap between the two, but they are not the same thing. Grella added that the meaning of the words in popular culture and the ideology are another dimension that further contributes to the disconnect.

Dean Kilpatrick (Medical University of South Carolina) commented that there are also relevant differences between a harm reduction model and an abstinence model. In other words, if somebody used to be drinking two quarts a day and now is drinking only one pint a day, some would describe that as a lot of improvement, while others would say that is very problematic.

THE MEANING OF RECOVERY FOR THOSE WHO SELF-IDENTIFY AS “IN RECOVERY” FROM SUBSTANCE USE

Laudet provided an overview of what is known from research studies she has worked on about how people in recovery from substance use think of the concept of being in recovery. The first two studies discussed by Laudet were both conducted in New York City and funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. One of the studies was a community-based study of 354 people recruited through ads and flyers and followed for 3 years.15 The goal of this study was to elucidate patterns and psychosocial predictors of stable abstinence. Laudet noted that she considers it important that recovery studies not be limited to treatment-based samples because recovery is not limited to treatment contexts. The second New York City study involved 250 individuals who were recruited from two 12-step programs after entering outpatient treatment and followed for 1 year. The goal of this study was to identify predictors, patterns, and outcomes of participation in 12-step programs.

The third study discussed by Laudet was the Life in Recovery study, which was commissioned by the Faces & Voices of Recovery organization in 2012. The study was a Web-based nationwide study, which recruited 3,208 participants. As others have mentioned, she said, recovery from substance use is more than abstinence and supporting individuals in recovery involves more than supporting abstinence. One goal of this study was to document experiences at successive stages of recovery to identify service needs for a recovery-oriented system of care. Another goal was to document the perceived benefits of sustained recovery to individuals and to the nation.

One question that was examined by the community-based New York City study was why substance users quit using. Laudet said that the findings showed that people seek recovery primarily because they want a better life. More than 90 percent of the respondents in the study provided such answers as didn’t like where life was going or feared consequences, desired a better life, and were tired of the drug life. Participants were also asked what were their current priorities in life. The most important priority was “recovery work,” in other words, staying clean, followed by employment. Mueser noted that this is an interesting difference between substance use and mental health recovery, because “recovery work” as a concept would not come up in the context of mental health.

Laudet and her colleagues also asked the sample entering outpatient treatment about priorities and found that staying clean and employment

___________________

15Laudet, A.B. (2007). What does recovery mean to you? Lessons from the recovery experience for research and practice. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 33(3), 243-256.

were also the main priorities for this sample, which was at an earlier stage in the recovery process.16 She argued that learning about priorities is important because the main goal of recovery support services should be to help people reach their goals, assuming that these goals are good for the community and society.

Another question examined by the researchers was whether recovery leads to a better life. They asked study participants to talk about what, if anything, is good about being in recovery. The most frequently mentioned responses were in the categories of a new life; a second chance; a drug-free, clear head; and self-improvement.

Laudet said that the community-based New York City study also evaluated stress and quality-of-life satisfaction as a function of abstinence duration.17 These factors are important because stress is one of the main predictors of relapse. The study found that stress decreases significantly as a function of the duration of one’s recovery from drug and alcohol problems. Quality of life appeared to continue to grow until about 3 years after the beginning of abstinence.

Findings from the Life in Recovery18 survey showed that the rates of positive experiences increase as recovery progresses. The improvements include experiences related to family and social life, such as participating in family activities, volunteering, and voting. They also include health-related improvements, such as healthy nutrition, exercise, and medical care. Conversely, the rates of negative experiences decrease as recovery progresses. Laudet said that the findings from the Life in Recovery study underscore what Hillman had noted earlier—that positive experiences not only increase drastically from active addiction to recovery, but they continue to increase over the years.

Participants in the New York City community-based study were also asked directly, in an open-ended format, how they would define recovery from drug and alcohol use.19 Laudet agreed with previous speakers who pointed out that, in its current form, the SAMHSA definition is too broad and so would be difficult to measure. In this study, a better life or new

___________________

16Laudet, A.B., and White, W. (2010). What are your priorities right now? Identifying service needs across recovery stages to inform service development. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 38(1), 51-59.

17Laudet A.B., Morgen, K., and White, W.L. (2006). The role of social supports, spirituality, religiousness, life meaning, and affiliation with 12-step fellowships in quality-of-life satisfaction among individuals in recovery from alcohol and drug problems. Alcohol Treatment Quarterly, 24(1-2), 33-73.

18See http://www.facesandvoicesofrecovery.org/sites/default/files/resources/Life%20in%20Recovery%20Survey.compressed.pdf [May 2016].

19Laudet, A.B. (2007). What does recovery mean to you? Lessons from the recovery experience for research and practice. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 33(3), 243-256.

life was the most frequently mentioned response regarding the meaning of recovery (44%), followed by total abstinence (41%). Other categories of responses mentioned were a life-long process (21%) and dealing with issues (17%). Laudet said that these responses illustrate that recovery from substance use is a multidimensional concept, which includes improvements in the areas of life that had been impaired by active substance use, as well as sobriety or reduced substance use.

A related concept discussed by Laudet was quality-of-life satisfaction, which she argued can help sustain recovery. Her research has found that baseline quality-of-life satisfaction predicted sustained abstinence 1 and 2 years later. For outpatient clients, quality-of-life satisfaction at the end of treatment predicted level of commitment to abstinence, which has been found in other studies to predict actual abstinence.20

Mueser remarked that the association between abstinence and improvements in various life domains makes sense. However, it is important to remember that many people have co-occurring substance use and mental health disorders, and for these people improvements are less likely to automatically happen when they stop using. Mueser argued that this is why it is important to be able to provide psychosocial rehabilitation to help people get back to work and improve the quality of their relationships, not just when they become abstinent but in order to foster that abstinence over the long run. Hortensia Amaro (University of Southern California) commented that this is a special concern in the case of people with a history of trauma. She said that her work with women who have a history of trauma indicates that there are often new symptoms that emerge when the person stops using drugs or alcohol. She argued that treatment has to factor in this phenomenon and provide the tools and context necessary to prevent relapse.

Peter Gaumond (Office of National Drug Control Policy) agreed that in some cases abstinence can result in diminished quality of life. He suggested that the best way to think about it is as a tool for achieving recovery because most people are not going to be able to achieve an improved quality of life if they have a serious substance use disorder. Hillman agreed and added that in her view abstinence is very important during the initial stages of recovery, but at later stages it becomes a choice.

Salzer noted that Laudet’s presentation focused on the increased participation in social life as a result of abstinence, and his work indicates that

___________________

20Laudet, A., and Stanick, V. (2010). Predictors of motivation for abstinence at the end of outpatient substance abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 38(4), 317-327.

Laudet, A.B., Becker, J.B., and White, W.L. (2009). Don’t wanna go through that madness no more: Quality-of-life satisfaction as predictor of sustained remission from illicit drug misuse. Substance Use & Misuse, 44(2), 227-252.

sometimes increased participation, such as returning to work or school, dating, or parenting, can also be a precursor to a decrease in symptoms in the mental health context. This outcome may also be true for substance use. In other words, the association between recovery and increased participation is likely bidirectional. He added that SAMHSA’s definition captures this multifaceted aspect of recovery.

This page intentionally left blank.