5

Defining and Operationalizing Recovery from Mental Disorders

This chapter summarizes a presentation by Kim Mueser (Boston University) on definitions of recovery from mental disorders and their implications for measurement and a presentation by Corey Keyes (Emory University) on the role of positive mental health in operationalizing recovery.

DEFINITIONS OF RECOVERY FROM MENTAL DISORDERS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR MEASUREMENT

Mueser discussed the definition and operationalization of recovery from mental disorders. As previous speakers indicated in the context of recovery from substance use, he noted, there are two main categories of definitions of recovery in the area of mental health. One category is the traditional medical definition, which is a below-threshold level of symptoms and the absence of significant associated impairment. The other category is personal definitions, which center primarily around the experience of recovery from mental illness. These definitions often allude to people’s current appraisal of their mental illness, as well as their perceptions of changes in their mental illness. The definitions also reflect the importance to individuals of functioning well in such areas as social relationships, work, and self-care, regardless of symptoms.

An example of a broad personal definition is one developed by William Anthony: “Recovery involves the development of new meaning and purpose in one’s life as one grows beyond the catastrophic effects of

mental illness.”1 Mueser noted that this definition is largely subjective, although the notion of meaning and purpose implies behavior.

Mueser turned to one question that has been raised in the workshop: What are people recovering from? In the strictest sense, they are recovering from mental illness, but as other speakers have noted, mental illness has an impact on functioning and could lead to loss of self-worth, self-esteem, and self-efficacy, which also require recovery by those who are affected.

Some people are also recovering from trauma, which could include the traumatic effects of psychiatric symptoms, traumatic reactions to coercive treatments, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms. Mueser said that he and his colleagues conducted two studies that looked at what percentage of first-episode psychosis patients and multi-episode hospital patients met the symptom criteria for PTSD related to either symptoms or coercive treatment: in both studies, the number was around 60 percent. A somewhat larger number of people reported that the symptoms themselves were the most terrifying, but many indicated coercive treatment experiences. Some people reported that both of these experiences were traumatic. In addition to PTSD-related to mental illness, it is well understood that traumatic events in general increase vulnerability to psychiatric disorders. In other words, Mueser said, it is also important to remember that some people have comorbid PTSD.

A second definition of recovery from mental disorders discussed by Mueser was one proposed by Patricia Deegan:2

Recovery is a process, a way of life, an attitude, and a way of approaching the day’s challenges. It is not a perfectly linear process. At times our course is erratic and we falter, slide back, regroup, and start again. The need is to reestablish a new and valued sense of integrity and purpose within and beyond the limits of the disability; the inspiration is to live, work, and love in a community in which one makes a significant contribution.

Mueser noted that this definition is quite nuanced and includes many dimensions of the subjective experience. The definition also focuses on functional outcomes and identifies different areas of functioning as priorities.

One of the challenges for measuring recovery from mental disorders is being able to identify areas of convergence between the medical

___________________

1Antony, W.A. (1993). Recovery from mental illness: The guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal, 16(4), 11-23.

2Deegan, P.E. (1988). Recovery: The lived experience of rehabilitation. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal, 9(4), 11-19.

definitions and the personal definitions of recovery. Mueser argued that several objective measures of psychosocial functioning (such as social functioning, work, school, and independent living) are related to both the medical and personal definitions of recovery. There is some evidence that more severe symptoms, especially depression and psychotic symptoms, tend to be associated with lower well-being, self-esteem, and self-efficacy. There is also some evidence that indicates that better psychosocial functioning is related to higher subjective well-being and related constructs. For example, when people with serious mental illness obtain competitive work, there is often a modest increase in their self-esteem and self-efficacy, and there are reduced mood symptoms.

Mueser said that although combining the objective and subjective definitions of recovery from mental disorders is challenging, one option is to define recovery in terms of psychosocial functioning, which is the area of greatest overlap in definitions. This in turn can lead to the development of models that integrate symptoms, objective functioning, and subjective experience.

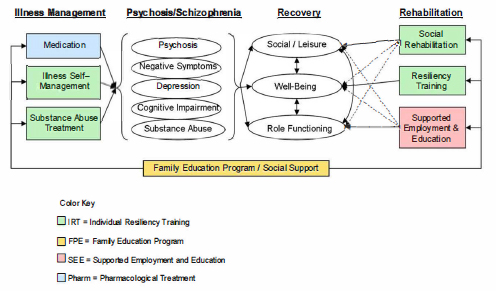

Mueser described a treatment model that he and his colleagues developed as part of the NAVIGATE Program, which is a comprehensive, coordinated specialty program designed for people experiencing a first episode of psychosis. In this program, recovery is defined as functioning in the social and leisure domains, a broadly conceptualized sense of wellbeing, and role functioning. Figure 5-1 shows how this conceptualization of recovery interacts with different dimensions of the illness in this model.

The different dimensions of the illness (such as psychosis, negative symptoms, depression, cognitive impairment, substance abuse) can hinder recovery, but Mueser said that one can design interventions that specifically target these dimensions, such as medication or training in illness self-management. Other interventions can target recovery outcomes directly by providing support, teaching skills, or rehabilitation-based interventions. Figure 5-1 illustrates that it is possible to integrate the different dimensions of recovery into an overall treatment model.

Mueser pointed out that there are nonetheless limitations to the convergence. First, recovery is nonlinear in nature. Recovery in one area of psychosocial functioning tends to be only very weakly correlated with recovery in other areas. In general, psychosocial treatment effects tend to be domain specific, with minimal impact on other areas of functioning. In other words, interventions that improve functioning in a work context tend to improve functioning only in that area and not generalize to other areas. For example, people can be going to work, but continue to have a very poor social life, which makes it difficult to develop a single definition of functional recovery. In addition, there is only a modest relationship between

SOURCE: The NAVIGATE Team Members’ Guide. Available: https://raiseetp.org/studymanuals/Team%20Guide%20Manual.pdf [May 2016].

symptom severity and functional outcomes (e.g., relationship between cognition, psychiatric symptoms, and work).

Mueser noted that there are difficulties associated with mapping some aspects of subjective experience (such as self-determination, hope) onto objective indicators of functioning. A somewhat related point is that associations between psychosocial functioning and subjective evaluations are much stronger in the case of people with mood disorders than people with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Reality distortion may influence one’s ability to accurately perceive the quality of one’s own functioning. Mueser noted that in schizophrenia-spectrum disorders, good insight is a well-known predictor of better psychosocial functioning over time. However, insight in the case of schizophrenia is also related to worse mood and worse subjective experience. The likely reason for this is that when people are asked to rate their own psychosocial functioning, they are really being asked to compare themselves to other people, and those who have a lot of reality distortion do not see the discrepancy, which could lead to negative emotions. At the same time, Mueser said, being able to see the discrepancy can serve as the fuel for participation in recovery-oriented programs.

These issues illustrate that the nature of recovery reflects the heterogeneity in the impact of mental illness on people’s lives, as well as in the process of improvement. Mueser argued that there is no single objective or

subjective definition that is going to be sufficient to encompass the entire concept of recovery. Consequently, there is a question of whether objective and subjective recovery can be connected on the personal level. Mueser noted that there are different dimensions of recovery that are important to characterize in order to understand the relationships. He argued that there is value in maintaining a broad distinction between objective and subjective aspects of recovery and proposed the conceptualization of a “recovery profile” aimed at measuring multiple critical dimensions of recovery. This notion is similar to the multidimensional conceptualization of recovery mentioned by others, which can accommodate both objective and subjective aspects of recovery.

Mueser listed both the objective and subjective dimensions of recovery that he argued would need to be included in a recovery profile: see Box 5-1. The objective dimensions include various aspects of role functioning, mental and physical health, independent living, and social

functioning. Mueser said that all of these dimensions can be measured. A list of subjective dimensions he tentatively proposed include aspects of well-being, sense of purpose, and internal and external processes related to mental illness. He noted that the internal processes related to mental illness are the processes that a person goes through within themselves, while what he labeled external processes are in fact active strategies that a person may be using in order to manage the mental illness.

To explore the potential relationships between objective and subjective dimensions of recovery and the utility of thinking in terms of a recovery profile that includes both dimensions, Mueser used the examples of sense of purpose and role functioning. Sense of purpose is related to what one does, such as work, school, or parenting, but not enough is known about the connection between sense of purpose and other subjective aspects of recovery. It is likely that improved role functioning enhances a person’s sense of purpose, but this likelihood raises the question of the effects of creating new valued roles for a person with mental illness on her or his sense of purpose and other aspects of both subjective and objective recovery.

In terms of the implications for measurement, Mueser argued that there are both objective and subjective dimensions of recovery that do not map to one another. Moreover, the different aspects of these dimensions are also not highly correlated, so that it is not possible to create a single measure of recovery. A recovery profile that includes both objective and subjective dimensions presents a possible solution. The multiple measures of each dimension already exist, but there is no systematic approach to collecting or combining information or for interpreting the scores. In addition, he said, it is doubtful that it would be feasible to collect all relevant information by combining existing instruments because of the participant and research burden. Relying on existing measures could also be problematic if some of the measures are taken out of context.

Mueser argued that developing a new instrument would be useful to measure the recovery profile. A systematic approach with a single instrument would have the advantage of facilitating research, and it could also become a potential tool for individual treatment planning and the review of progress toward goals. He noted that the field of serious mental illness has been in need of such a standardized outcome measure for the last 30 years.

Corey Keyes (Emory University) commented that a particularly useful feature of a new instrument of this type could be to provide participants with the results of the survey after the interview. People in recovery could benefit substantially from receiving that information from researchers.

Grella noted the emphasis on hope and empowerment that characterizes discussions around recovery from mental illness, in contrast with the

12-step approach in the area of substance use recovery, in which one has to admit powerlessness. She noted, however, that there are some distinctions embedded in the terminology that have to do with the different orientations historically of treatment across those two domains.

Mueser agreed that in a sense the concepts of recovery are almost diametrically opposed in the two areas. Recovery in substance use disorders means that one can have a life as long as one stops using substances, while the concept of recovery in mental illness is that one can have a life even if one continues to experience symptoms. The difference, Mueser said, is that there is a perception of greater control over substance use than mental health symptoms. In addition, in the area of mental illness, the emphasis of hope is partly aimed at countering the negative messages that psychiatry has communicated over the years about major mental illnesses, such as telling people with schizophrenia that they will never be able to work.

Laudet pointed out that another difference between the two areas is that drug use is illegal, which has led to the perception that a person is either using and is a criminal or is not using and then can be put “back into the fold.” Mueser added that the issue of stigma surrounding mental illness is another consideration. There is a perception to some extent that as long as a person with a prior drinking problem is not drinking, he or she can do anything and can be trusted. But the stigma associated with admitting to having had a mental illness or mental health treatment is much more difficult to overcome, even if it happened 20 years ago.

Hortensia Amaro (University of Southern California) noted that there is discussion of the role self-initiated and self-directed trajectories in both substance use and mental illness recovery. However, some treatment is imposed, and the treatment process is also fairly directive. She wondered how the focus on self-agency in definitions of recovery can be reconciled with externally directed treatment situations in the context of measurement.

Mueser replied that for some mental health consumers, self-agency is critical in terms of getting into recovery and rebuilding their own lives. Because of that, the principle of respecting self-agency and capitalizing on it is important. However, the strength of a multidimensional definition of recovery is that it also reflects the fact that for many consumers recovery means a good place to live, good-quality social relationships, and work, and there are many ways to achieve those goals. In addition, as others have pointed out, there are many people who do not relate to the concept of recovery at all. Some may not relate to many of the subjective elements of recovery, but they are relatively satisfied with life and would score high on measures of the objective dimensions of recovery.

Kenneth Wells (University of California, Los Angeles) noted that there are several recent measures of recovery that are multidimensional. One

example is the Maryland Recovery Measure, which includes questions on self-agency and self-efficacy. These items do not appear to be strongly associated with direct functioning and clinical outcome measures when the data are analyzed; rather, they form their own distinct self-efficacy domain.

James Jackson (University of Michigan) asked what the criteria would be for determining, in a general population survey, who would be asked questions about recovery. Mueser replied that he would focus on people who have some prior indicator of severe and persistent mental illness. He argued that including everyone who has had a psychiatric illness would be too broad, in part because most of what researchers know about the subjective aspects of recovery from mental disorders is from working with people with severe and persistent mental illness. Including a broader range of psychiatric illnesses could present a measurement challenge. In addition, the most underserved populations are people with severe and persistent mental illnesses, mainly schizophrenia spectrum and mood disorders with PTSD or co-occurring substance disorders, and the impact of mental illness on their lives, as well as the disabilities they experience, are relatively more severe.

Jackson commented that Mueser’s points suggest that to determine who should be asked about recovery, an impairment criteria could be applied, instead of specific diagnoses. This approach could be applied to both substance use and mental disorders. He added that one commonality between substance use and mental disorders that has not been discussed is that people with substance use problems often have cravings that could be described as conceptually similar to symptoms. In both cases, such a craving may be fine as long as the person is not acting on it. These types of commonalities are useful to consider as part of the discussion of a study design to measure recovery.

Wells said that although he understands the value of focusing on the severely ill population, there might be some advantages to a dual strategy. One strategy would be to develop a design targeted at understanding the issues associated with behavioral health resiliency and wellness for the general population. The other strategy would be focused on the subset of the population with severe mental illness and the specific issues relevant to them. This dual strategy would also help with providing some context for the data from those who are in recovery from severe mental illness.

THE ROLE OF POSITIVE MENTAL HEALTH IN OPERATIONALIZING RECOVERY

Keyes began his presentation by saying that health has traditionally been defined as the absence of illness or disease and that he is particularly

passionate about trying to unpack mental health as more than the absence of mental illness. As part of his research, he looked back at the ancient Greeks, including Epicurus and Aristotle.

Keyes noted that happiness is one of six basic emotions that are all adaptive and functional in their own way but can become a problem when they persist for too long and in a way that is too strong. The function of happiness is to help people encode and memorize things that are good for us. This system can get hijacked by addiction and other problems, but positive mental health must consist of happiness.

Epicurus’ philosophy was that a good life consists of pleasure or positive emotions, and generally the avoidance of unnecessary pain. Keyes said that this interpretation of happiness focuses on emotional well-being. Accordingly, one approach to measuring happiness involves items from the Mental Health Continuum Short Form, which asks people to think about the past month—using a scale from never to every day—to say how often they felt happy, how often they felt satisfied with life, and how often they felt interested in life.

Keyes said that another tradition of happiness originates from Aristotle, who said that happiness is not first and foremost about feeling good, but about excellence and about functioning well in life. He and his colleagues operationalized this interpretation in two ways: as psychological well-being and as social well-being.

Psychological well-being includes self-acceptance, positive relations with others, personal growth, purpose in life, environmental mastery, and autonomy. Keyes said that these items were part of a list that was developed by social psychologists in the 1940s to inform the work of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). He noted that positive mental health was part of the discussion when NIMH was created but is only now receiving serious attention.

To measure happiness, operationalized as psychological well-being, Keyes and his colleagues asked study participants to think about the past month and answer such questions as whether they liked most parts of their personalities, had warm trusting relationships with other people, were being challenged to become a better person, felt that their lives had direction and meaning, were able to manage their lives, and were confident that they could express their own ideas and opinions.

The social well-being operationalization of happiness includes social acceptance, social integration, social contribution, social coherence, and social growth. To measure these dimensions, Keyes and his colleagues asked people questions about whether they trust and like other people; belong to a community in which they derive a sense of comfort and joy; feel that what they do on a daily basis contributes value and worth to the world; are able to make sense of what is going on around them in their

social groups, institutions, or society; and are being challenged as a member of units, families, teams, and in workplaces to become a better person.

Keyes said that despite a tradition focused on positive feeling and positive functioning, when researchers began studying well-being, the emphasis was on depression. In public health today, there is a lot of talk about well-being and health and the need for a mentally healthy population, but what is studied is mental illness. He noted that the concept of flourishing turns the diagnosis of depression on its head, referring to the presence of good mental health.

Keyes said that to be diagnosed as flourishing one has to have had, every day or almost every day in the past month, 6 of any of the 11 positive functioning characteristics that he listed as being part of psychological and social well-being, combined with at least 1 of the 3 emotional wellbeing items. In other words, 7 out of 14 items are required based on the definition. He noted that the distinction between functioning and feeling is a very important one.

Keyes said that the factor structure in this approach has been replicated not only for adults, but also for adolescents aged 12 and older and in populations outside of the United States. Item-response theory analysis shows that there is no differential item function in the 14 items by race, gender, or by disease function over time. There is also no differential item function cross-culturally.

The hypothesis behind a two-continua model—of mental health and mental illness—is that mental health is more than the absence of mental illness. One of the continua is that of mental illness, from low mental illness to high mental illness. This is the continuum that has traditionally received the most interest. However, Keyes argued, a second continuum from low mental health to high mental health also needs attention. This continuum measures the presence and absence of emotional, psychological, and social well-being.

Keyes said that studying the mental health continuum is important because the absence of mental illness does not mean that a person is flourishing. In fact, studies indicate that the vast majority of the population is not flourishing. This finding represents a large burden to populations, but the problem appears to remain invisible to public health because one has to become diagnosed with a disorder in order to be treated.

Another point of the two-continua model Keyes highlighted is that just because one has a mental disorder, or had a mental disorder in the recent past, does not mean that the person does not have some level of well-being. Of course flourishing with mental illness is quite rare, but it does happen. The most common occurrence is that people who have mental illness have moderate mental health, and it is rare that people

are languishing, which would be the complete absence of mental health combined with mental illness.

Data show that level of mental health determines how well people function with a mental disorder. Keyes argued that recovery is not just about being symptom free, but rather a movement toward flourishing. Stated another way, any movement toward flourishing is a movement toward recovery.

Keyes said that flourishing is not just an artifact of people’s minds. He and his colleagues have been studying the genetics of positive mental health along with mental illness, based on a nationally representative sample of adult twins. Using these data, the best-fitting model indicates that the three types of well-being (emotional, psychological, and social) have a single genetic source, and it is 72 percent heritable. There were no differences observed in the model between men and women.

The data also show that less than one-half of the genetic variance for mental disorders, such as depression, is shared with the genetic variance for flourishing. This finding means that one can inherit a high risk for depression, but can also inherit a high genetic propensity for flourishing. However, being free of a genetic propensity for depression does not mean being free of a risk of poor mental health, if one inherits a low genetic propensity for flourishing.

Keyes discussed several studies that illustrate implications of the two-continua model. One was the Healthy Minds Study, a survey of university students.3 Using the Patient Health Questionnaire, approximately 13 percent of respondents screened positive for a mental disorder, such as depression, panic attacks, or generalized anxiety. The total included 3 percent of students who were flourishing, 8 percent who had moderate mental health, and 2 percent who were languishing. In other words, the data showed that the presence of mental illness does not mean the complete absence of mental health. The data also showed that the absence of mental illness does not necessarily mean flourishing. The researchers found that less than half of the students had good mental health, and 39 percent were not flourishing, which Keyes pointed out is worse than what one would observe in the general adult population. He argued that the problem is twofold: the rates of mental illness are too high, and the rates of mental health are too low.

Keyes said that another implication of the two-continua model is that, with or without a mental disorder, anything less than flourishing can result in serious problems. The second study he described was one conducted by researchers at the Mayo Clinic who studied medical stu-

___________________

3See http://healthymindsnetwork.org/hms [June 2016].

dent well-being.4 The study followed more than 3,000 students at seven medical schools from their first through their fourth year. The study found that serious thoughts of dropping out and prevalence of suicidal ideation increased as mental health decreased from flourishing, to moderate, to languishing.

Another implication of the two-continua model is that the absence of flourishing can be as bad as the presence of mental illness. Keyes described the Midlife in the United States Study, which was based on a nationally representative sample of the U.S. population and included several follow-up surveys.5 The study found that depressed adult miss an average of nearly 23 days of work annually. Those who were free of diagnosis in the past year but were not flourishing missed 5-1/2 days annually, while those who were free of diagnosis and were flourishing missed 2 days. When the number of days are multiplied by the number of people in each category, it becomes clear that not flourishing is associated with more days missed annually than depression. Of 15,062 missed workdays, 5 percent were among those who were flourishing, 52 percent were among those who were free of mental disorder but not flourishing, and 43 percent were due to mental disorder, including depression, panic attacks, and generalized anxiety. In this study, respondents were also asked about days when they did not miss work but they were not able to perform all their duties, left early, as well as about medical visits for both physical and mental reasons, and the patterns were similar. In other words, in addition to mental illness, not flourishing is also a substantial problem, and in some cases can have a bigger impact on days missed and the number of medical visits than the presence of mental illness itself.

The final implication of the two-continua model discussed by Keyes was that health may be more serious than illness. In other words, health and its loss are in some ways more important than illness because data shows that it is the loss of good mental health that precede and elevate the risk of disorders such as depression, panic attacks, generalized anxiety. Data from the Midlife in the United States Study showed that in 1995, 18.5 percent of the adult population fit the criteria for one of those three mental disorders.6 When the sample members were reinterviewed in 2005, 17.5 percent fit the criteria. The overall percentages did not change, however:

___________________

4Liselotte, N.D., Harper, W., Moutier, C., Durning, S.J., Power, D.V., Massie, F.S., Eacker, A., Thomas, M.R., Satele, D., Sloan, J.A., and Shanafelt, T.D. (2012). A multi-institutional study exploring the impact of positive mental health on medical students’ professionalism in an era of high burnout. Academic Medicine, 87(8), 1024-1031.

5See http://midus.wisc.edu/ [June 2016].

6Keyes, C.L., Dhingra, S.S., and Simoes, E.J. (2010). Change in level of positive mental health as a predictor of future risk of mental illness. American Journal of Public Health, 100(12), 2366-2371.

52 percent of the cases in 2005 were not cases in 1995. What the researchers found was that being free of mental disorder but not flourishing in 1995 created threefold to eightfold risk of having mental disorder in 2005, compared with the risk associated with flourishing. In other words, in comparison with being mentally healthy, anything less than flourishing results in elevated risk of developing mental illness.

Another study discussed by Keyes collected data from medical interns every 3 months over the course of 1 year.7 The researchers found that changes in flourishing, using the measure developed by Keyes, preceded elevations of the risk of depression.

A study of a representative sample of Dutch adults, which also involved four data collections over time, found reciprocal causal connections between positive mental health and mental illness.8 In other words, recovery and treatment for mental illness results in improvements in good mental health, while losses of good mental health increase subsequent risk of psychopathology.

Keyes said that the recovery goal is complete recovery, and in recovery a person is flourishing. However, when one has a mental disorder, any improvement in good mental health is a sign of movement toward recovery, and several recent studies have underscored this point.9 He argued that measures of recovery should include some elements of flourishing. If flourishing can prevent the onset of mental illness, it is possible that it can also prevent relapse of mental disorders and substance use disorders; more studies would be needed to determine if this is so.

Steven Fry (SAMHSA) commented that the discussions have reflected a lot of agreement that recovery happens, is valid, is accepted, is multidimensional, and that there are many ways of getting there. Accordingly, there are also many different ways of measuring it. However, there is also prejudice, discrimination, and an unwillingness to intervene until there is a crisis. In addition, he noted, education in schools could equip people with a vocabulary about mental health and emotional well-being. He said that he would like to see the vision of recovery described by Keyes widely

___________________

7Grant, F., Guille, C., and Sen, S. (2013). Well-being and the risk of depression under stress. PLoS One, 8(7), e673-e695.

8Lamers, S.M.A., Westerhof, G.J., Glasb, C.A.W., and Bohlmeijera, E.T. (2015). The bidirectional relation between positive mental health and psychopathology in a longitudinal representative panel study. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(6), 1-8.

9Fledderus, M., Bohlmeijer, E.T., Pieterse, M.E., and Schreurs, K.M. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy as guided self-help for psychological distress and positive mental health: A randomized controlled trial. Psychological Medicine, 42(3), 485-495.

McGaffin, B., Deane, F.P., Kelly, P.J., and Ciarrochi, J. (2015). Flourishing, languishing, and moderate mental health: Prevalence and change in mental health during recovery from drug and alcohol problems. Addiction Research and Theory, 23(5), 351-360.

disseminated to make it possible to detect and arrest mental disorders at the earliest stages and to give people the tools to improve their quality of life.

Mark Salzer (Temple University) said that the role of flourishing underscores the importance of measuring these types of constructs among a broad range of people, in addition to those with serious mental illness. He said that one of his concerns is that recovery is a complicated concept and, as the discussions have illustrated, has a variety of definitions. He asked Keyes whether he thought that measuring flourishing could replace measuring recovery altogether.

Keyes answered that he would like to think that the field can mature and perhaps grow out of the concept of recovery, because it would shift the focus to facing something positive, not something that was left behind. However, he does not think that measuring recovery can be replaced now because research in these fields is in the early stages. Recovery from mental illness is an important goal, shared by many people. It is a rallying call and what helps them face life and its challenges with meaning. From a measurement perspective, Keyes said, it is important to remember that the two-continua model suggests that one can have a mental disorder and be moving toward recovery, but for others being free of mental disorder may never be possible though they may be moving toward flourishing.

Michael Dennis (Chestnut Health System) commented that ultimately what people want is a normal life, and that could mean not just having a job and a house, but also having well-being and having a sense of happiness. It has been argued through the workshop that recovery is a process, and if so, Dennis said, then measuring the values that one aims to achieve is the most straightforward approach, which can apply across both substance use and mental health and even other health conditions.

Kenneth Wells (University of California, Los Angeles) commented that as part of developing the Community Partners in Care Study that he discussed earlier (see Chapter 2), the researchers worked with people in the community to determine their main goals in recovering from depression, which was the focus of the study. The framing the respondents favored to describe what they wanted was mental wellness. Consequently, the researchers included in the study questionnaire items on happiness, peace of mind, and energy, which matched the words the respondents had used. In looking at the outcomes of the study, the largest effect of the intervention was on mental wellness. There also was an effect on distress, which is in line with the duality argument, but the largest effect was on what the participants valued the most. This outcome was particularly pronounced among Latino study participants. Another observation from the study, Wells noted, is that Latinos, especially men, do not like to say that they are depressed, but they are willing to say that they are not completely

happy. In other words, capturing outcomes in a way that is meaningful to participants in a diverse population study is particularly challenging.

Benjamin Druss (Emory University) said that Mueser’s presentation suggested that the objective measures of recovery are particularly relevant for those who are in recovery from serious mental illness. He wondered whether the functioning measures also fit into a continuum model. Mueser said that they do, and he clarified that he considers functioning measures especially important for people with serious mental illness because they are more changeable than the underlying subjective aspects of recovery. However, he said, measuring positive mental health as described by Keyes would nonetheless be useful. He noted that flourishing seems subjective, but it is also more related to a person’s day-today functioning than some of the other subjective aspects of recovery.

Hortensia Amaro (University of Southern California) summarized several themes that she said emerged from the discussions. One theme is that recovery is an ongoing process, and it involves engagement in and movement toward a set of aspirations. Another theme is that recovery is multidimensional, that one could be doing well in one area but not in another, that there are different factors that facilitate recovery, protective factors, and also risk factors, and that those can occur at the individual, family, and community levels. The concept of a recovery profile was noted by many speakers, as was the importance of capturing the objective and subjective dimensions of recovery. The notion of measuring flourishing adds another dimension to thinking about recovery.

This page intentionally left blank.