6

Communicating with the Public

The final session of the workshop examined two aspects of conveying information to the public about precision medicine. Kathleen Hickey, a cardiac nurse practitioner and an associate professor of nursing at Columbia University Medical Center, discussed precision medicine from the perspective of the nursing profession, and Chris Gunter, the director of communication operations at the Children’s Health Care of Atlanta’s Marcus Autism Center, addressed precision medicine in social media. Jennifer Dillaha, the medical director for immunizations and the medical advisor for health literacy and communication at the Arkansas Department of Health, and Carla Easter, the chief of the Education and Community Involvement Branch of the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), then provided their reactions to the two presentations, and Catina O’Leary, the president and chief executive officer of Health Literacy Missouri, moderated an open discussion following the reactors’ comments.

A NURSING PERSPECTIVE ON HEALTH LITERACY AND PRECISION MEDICINE1

Kathleen Hickey has been a nurse practitioner in a cardiac clinic that sees patients and families with a variety of inherited cardia arrhythmias,

___________________

1 This section is based on the presentation by Kathleen Hickey, an associate professor of nursing at Columbia University Medical Center, and the statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

and in that role she has had to communicate very clearly and concisely what those conditions mean to the affected individuals and their families. She said that she had entered the field in an era prior to the sequencing of the human genome, yet even then she and her clinician colleagues knew that arrhythmias ran in families and that there were genes yet to be discovered that were playing a role in the sudden cardiac deaths they were seeing in these families. At the same time, a new technology was developed—the implantable cardioverter–defibrillator (ICD)—that could save lives, and she recounted how she had to adapt to the literacy of the patients and families at risk when she spoke with them about this new technology.

Some patients, she said, would want to see the actual device, to touch it. Others wanted to talk to a patient who already had one implanted to find out what it felt like to have the device inside the body and what a shock felt like. Some of the younger female patients would want to speak to other young women who might be planning a pregnancy. Patients wanted to know if they could exercise and if the device would affect their lives. “I had to adapt my speaking to the literacy of the patients and also pare information into soundbites they could understand,” Hickey said.

Then came the Human Genome Project and the discovery of many monogenic disorders that can cause arrhythmias and for which there are now genetic panels of tests to screen patients and identify those at risk for such conditions as long QT syndrome or Brugada syndrome. “This is very powerful information because unfortunately the first arrhythmia can be the last arrhythmia,” Hickey said. Now, in this era of precision medicine, she not only had to communicate about the therapies that existed but also about genetic testing and the meaning of the results from those tests for both patient and other family members who might be silently at risk.

Her first step to meeting that challenge was to develop her own literacy by attending the Summer Genetics Institute, a 2-month laboratory- and classroom-based course offered by the National Institute of Nursing Research. This experience, Hickey said, allowed her to learn the language and then be able to read and understand the growing literature concerning genetic testing and communicate that information to patients and families in clear and concise language. This training also allowed her to interact more effectively with other members of the health care team.

As she started evolving as a professional and working with these patients and families, she began to realize that there had been little research done on how having an ICD implanted affects an individual’s quality of life and perceptions of life and what the long-term implications were of having a positive or negative genetic test result. One study that she and her colleagues conducted (Hickey et al., 2014a) found that patients were able to integrate a diagnosis over time into their lives and that a positive genetic test did not have a profound impact on quality of life. In another study,

Hickey and her collaborators examined what cardiac and genetic testing meant to their Dominican patients, who are often of lower health literacy (Hickey et al., 2014b). Through a series of qualitative interviews, she and her colleagues found these individuals were afraid of dying suddenly, regardless of whether or not they had the life-saving ICD device implanted inside them, and, if the device was implanted, they were afraid of getting shocked because they did not always completely understand that the ICD shock was what was terminating their arrhythmia and saving their lives. There was also guilt about passing on a mutation to their offspring, which is one of the real-world concerns clinicians need to address. Hickey noted that this work continues.

Hickey said she has been fortunate over the years to sit on many advisory boards and panels, often as the only nurse or nurse practitioner. One such panel, convened by the American Heart Association, found that there is a critical need for genetics and genomics competencies among cardiovascular and stroke clinicians (Musunuru et al., 2015). This panel developed a set of key content areas whose subject matter all cardiovascular and stroke clinicians should learn in order to avoid a big disparity between clinicians who understand this new language and those who do not. The panel then created a scientific statement with essential genetic/genomic content and developed a half-day boot camp for practitioners that the panel offered for the first time at the November 2015 annual meeting of the American Heart Association.

The boot camp was open to practitioners and non-practitioners alike, and anyone who wanted to attend was directed to a series of 16 preparatory videos to watch before the boot camp. The boot camp was designed to be an interactive experience, with breakout groups that would include nurses, statistical biologists, basic scientists, and clinicians looking at a series of challenging cases and discussing them. The dialog, Hickey said, focused on pedigree analysis, risk assessment, next-generation sequencing, pharmacogenetics, and the interpretation of common gene variants as well as some rare variants. As a facilitator in one of the breakout groups, Hickey said, she found a huge difference among practitioners in terms of subject matter literacy. She concluded from this experience that more of these types of activities will be needed going forward and that the field has to develop ways of educating the next generation of practitioners so that they can communicate clearly with the public.

Hickey has also worked with the American Academy of Nursing on recommendations for how advanced practice nurses can contribute to precision medicine (Williams et al., 2016). As their colleagues in other fields had done, the advanced practice nurses concluded that there is a need for genomic health literacy resources that are appropriate for people from diverse socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds. “We need to advocate

for these and test them in various populations, and we need to also make sure that the consents we are using for genetic information align with a person’s preferences,” Hickey said. She noted that as technology changes, patients’ information needs and the consent process may also change, and, as a result, developing appropriate materials and consent processes today will not be a one-time activity but instead will require ongoing research and development work.

Genetically trained professionals, Hickey said, are instrumental in taking comprehensive four-generation family pedigrees, ordering diagnostic testing, recognizing “red flags” and phenotypes of various genetic conditions, providing counseling and education, and supporting patients and families. From her experience working with genetic counselors as part of a health care team, Hickey has learned how important it is to put genomics into a context that is meaningful to the patient and to do so long before delivering the results of any tests. Patients need to know, starting from the first contact with the genetics professional, why they are there and why it is important that they provide a comprehensive family history, and practitioners need to understand the individual’s goals for seeking a genetic evaluation and recognize that sometimes this information may not be clear to the individual patient or family.

Health organizations have been playing an important role in educating both health professionals and patients about genomics, Hickey said. As examples, she mentioned the American Heart Association and the International Society of Nurses in Genetics, members of the latter were working with and caring for patients and families and communicating with the public regarding a variety of inherited disorders long before the Human Genome Project. The Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Association, StopAfib. org, and the Sudden Arrhythmia Death Syndromes Foundation are focused on inherited arrhythmia disorders, and Hickey said that what has impressed her about these organizations is that the founders themselves are affected by genetic conditions and have come together to change policy, to engage families, and to educate the public. These organizations have also worked to get automatic defibrillators installed in public places and schools and are getting schools to test children before they take part in sports.

Hickey also mentioned the work of the American Nurses Credentialing Center, which developed a new genomics competency for nurses. This competency, which was released in 2015, calls for nurses to have a portfolio they can submit that demonstrates their proficiency in genomics. She said that this type of credentialing activity will become increasingly important as precision medicine makes inroads into clinical practice. “This will be another way to support genetics counselors, geneticists, and other practitioners,” Hickey said, “and, quite frankly, there are not enough trained people to go around as we embark on the Precision Medicine Initiative.”

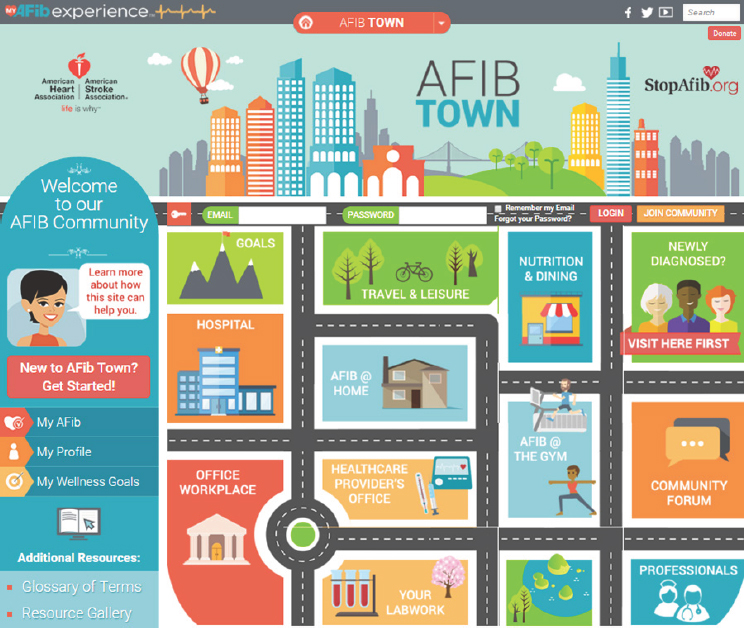

Working with the American Heart Association and StopAfib.org, Hickey and her research and clinical cardiology collaborators created a portal called AFIB Town (see Figure 6-1). This portal is designed for patients with atrial fibrillation, one of the most common cardiac arrhythmias, to get information, create their own profiles, and develop wellness goals, but it has also been used by providers who need information. Hickey’s said that her goal is to expand AFIB Town to include genomic information in the future and to make it possible for a clinician to access a patient’s information, including life history, medications, and symptoms, prior to meeting with the patient. Her hope, she said, is that similar types of portals could be developed as places where a clinician would create a precision or personalized care roadmap that would enable two-way communication between the clinician and the patient.

Hickey concluded her remarks by saying that health-literate communication in the era of personalized medicine is evolving and that it will take

SOURCE: Hickey slide 10.

a number of different types of professionals having various competencies and taking advantage of a range of advances in technology to produce the best outcomes for all individuals. She commented on how useful it might be someday to download information about a person’s physical activity from a wearable fitness monitor to an electronic health record and then add genomic information in a way that protects the privacy and advances the care of the patient.

PRECISION MEDICINE AND SOCIAL MEDIA2

In February 2016, the White House issued a fact sheet announcing key actions to accelerate the Precision Medicine Initiative (PMI). This fact sheet, Gunter said, listed 40 different affiliated projects with by different organizations nationwide. At least one-quarter of these organizations have stated explicitly that they will use social media and another 10 or so implied that they will use social media. The importance of this, she noted, is that for social media-driven efforts to be successful, they have to encourage two-way communication.

As an example of the power of a two-way social media approach, Gunter cited a paper in the journal Nature (MacArthur et al., 2014) that started as a discussion on Twitter she was having with a colleague, about a report that had appeared in the journal Science Translational Medicine in 2011 (Bell et al., 2011). The earlier paper had stated that 27 percent of the mutations that were identified when doing genome sequencing of children in neonatal intensive care and pediatric intensive care units and that had been cited in the literature as being deleterious mutations were actually common polymorphisms or had been annotated incorrectly. “As a geneticist, it was not acceptable to me that 27 percent of the time we are giving parents the wrong information,” Gunter said. She and her colleague were discussing their concerns about these findings via Twitter, and they decided to work with NHGRI to convene a workshop at which geneticists would develop guidelines and standards for investigating the causality of gene variants in human disease. Gunter said that, to her, an equally important part of the effort to develop standards was to get the word out about this paper and to stimulate discussion, so the group published in a multidisciplinary journal and used social media to publicize the paper, including Twitter and various blogs at NHGRI, the Simons Foundation for Autism Research, and a genome community called Genomes Unzipped, and they also worked with their own institutions to generate web articles. “This is the kind of action I

___________________

2 This section is based on the presentation by Chris Gunter, director of communication operations at the Children’s Health Care of Atlanta’s Marcus Autism Center, and the statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

encourage researchers to do,” Gunter said. “You have to get your research out there to reach the people who need to see it.”

What social media is good at achieving with respect to communicating advances to the public, Gunter said, is eliminating what she called the “middlemen” of both the media and institutional press offices. Most scientists interact with the public via their academic papers, clinical interactions, university courses, or working with university press officers and then getting upset when that person gets crucial details wrong. Gunter recommends using the whole range of new media: websites, blogs, Twitter and Facebook, videos and podcasts, and even public lectures, all of which represent new avenues for engaging the public. In a successful example, a colleague of hers used the internet news website Reddit to announce the creation of an online deletion registry for individuals with a rare 3q29 chromosome deletion and their families. Within 1 day of posting this announcement, two clinicians had already responded that they would tell their families about this registry. Gunter’s colleague reported that this was crucial in allowing her to contact a large number of families with this deletion.

Gunter’s organization uses its Facebook page to announce research studies and to let the autism community know about articles about autism and also to encourage discussion. She acknowledged that many researchers are hesitant to use Facebook in their professional lives, but she said she encourages them to get over that reluctance and accept Facebook as a means of increasing their connection with the public and getting their research into broader circulation on their terms. She said she is a proponent of Twitter for the same reason and explained that Twitter can be thought of as a site for “microblogging” and that it works best when updated frequently with varied content and when the tweets show some personality.

Prior to the advent of social media, mass communications researchers proposed a theory that the mass media disseminated important messages through a two-step process in which opinion leaders served as the conduit to individuals (Katz and Lazarsfeld, 1955). More than four decades later, Gunter said, researchers at Microsoft showed that the same holds true today, with information on Twitter going through a number of opinion leaders who then disseminate the message out to their friends and followers (Wu et al., 2011). Gunter said that she encourages scientists and clinicians to get on Twitter and be those key opinion leaders. For example, the 2014 International Meeting for Autism Research set up a room in which researchers and clinicians could field questions submitted via Twitter and tweet answers using the same hashtag. Over the course of an hour, this activity generated more than 4.3 million impressions, which represents the number of times those tweets went across the Twitter stream to everyone following that hashtag. “If only 10 percent of those people were actually online, and if 10 percent of those online were reading the tweets as they

came across, then potentially 43,000 people saw us saying that autism is not correlated with vaccines,” said Gunter, who called that a good science communication day.

Gunter then explained that autism is not only a spectrum of disorders, but that it is diagnosed by having traits on the spectrum of three different areas: social communication deficits, repetitive behavior, and restricted interests. She noted that at her institution, one of the nation’s largest centers for the care of autism, a diagnosis of autism in individuals referred to the clinic is confirmed only 60 to 70 percent of the time because her institution uses gold standard instruments that most referring clinicians do not use when making their provisional diagnosis. Due to the wide range of differences among autistic individuals, what precision medicine will be to the autism community specifically, and in mental health in general, is still up for discussion, Gunter said, and she encouraged the roundtable to continue thinking about health literacy in the context of behavioral and mental health.

“If there is any field that needs to have impeccable science communication, it is autism research,” Gunter said, referring to the belief held by some lay people that scientists want to do genetic research to eradicate autistic people. She acknowledged that while neither she nor any researchers she knows have that as the goal, the fact is that it doesn’t matter what researchers’ actual goals are in this extreme example; the autism community will never participate in or support research if its members believe this to be true. This situation, she said, points out the problem with the deficit model of science communication, which holds that people have a deficit of knowledge and if the scientific community can just remedy that deficit, then people will take predictable actions based on new knowledge. “That does not always happen because people’s heads are not empty, and they do not always make rational decisions with new information,” Gunter said.

Gunter referred to a recent study in which parents of children with autism and scientists were asked how the media has affected the public’s attitude toward individuals with autism (Fischbach et al., 2016). Ninety percent of parents and 88 percent of scientists thought the media did a good job of improving public attitudes toward individuals with autism and reducing the stigma associated with autism. However, while some 80 percent of the scientists said they would be interested in serving as a resource, only one-third of them actually were doing so. “That makes me very frustrated,” Gunter said. “We have to talk about our work and the challenges that are involved.”

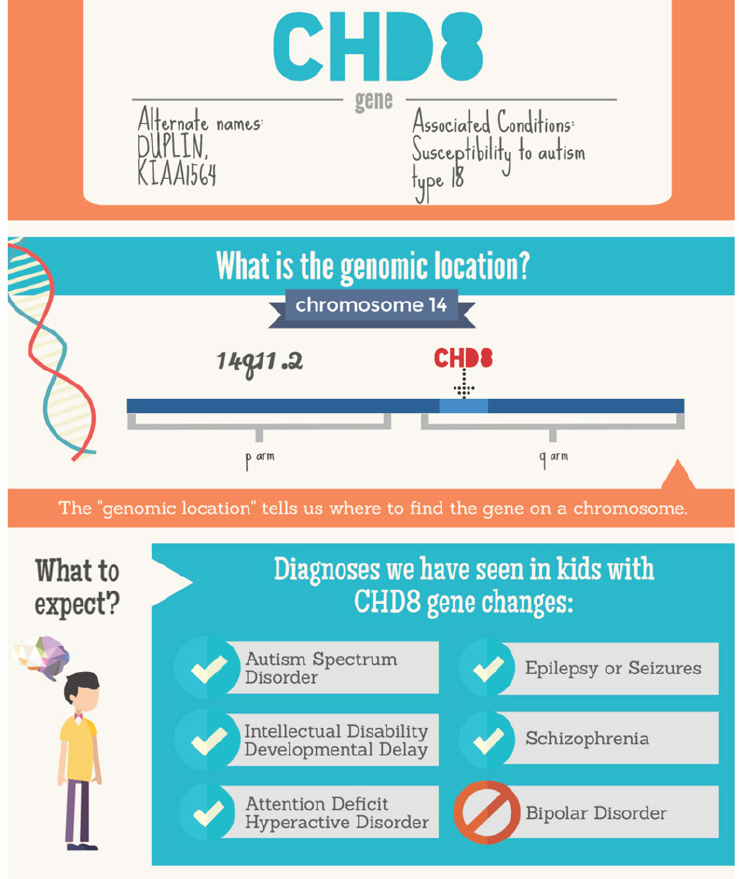

To illustrate some of the challenges that clinicians face in using social media to disseminate information, Gunter discussed the Simons Foundation for Autism Research VIP Connect Project, which in 2015 created autism resources specific to different genetic variants linked to autism. The project

has created infographics (see Figure 6-2) and webpages for each of the genetic variants and provided links to public communities and private Facebook groups as well as to research opportunities that arise. While all of this is great in theory, Gunter said, in practice the only people posting so far on the public Facebook page are people from the Simons Foundation, which

SOURCE: Gunter slide 18.

suggests that the Foundation still has work to do to get the community to engage with these resources. This is a common problem with building new outreach sites, Gunter said.

Another effort, which serves as an example of why thoughtful messaging and engagement are important in precision medicine, involves a collaboration between the autism advocacy organization Autism Speaks and Google whose goal is to sequence the genomes of more than 10,000 families affected by autism. Gunter said that similar projects aimed at sequencing the genomes of people with cancer to find genetic subtypes that link to specific diagnostics and treatments have been met with enthusiasm. The autism community, however, does not respond the same way, however, and the response to the project has been muted. The project has been hampered, too, by its name, MSSNG, which seems to imply that people with autism are missing something—an impression that prompted the creation of the hashtag #notmssng on social media. Gunter quoted the autism self-advocate John Elder Robison, who said, “In the context of a research initiative, this is at best insensitive and at worst seriously offensive.” Communication about any project will also affect what institutions planning to collect DNA for sequencing, such as Gunter’s own genetics group, decide about whether to be affiliated with this project.

In her closing remarks, Gunter explained that different members of the autism community prefers different terms to describe autism (Kenny et al., 2015). It is incumbent on the research and clinical communities to ask people which term they prefer and not let this be a barrier to communicating with the members of a given community. Gunter also noted that just using social media is not enough to achieve good bidirectional communication. “You need to have a thoughtful plan for engagement to go with it,” she said. “You need to listen to what the community wants and even what they want to be called.” In the behavioral and mental health areas in particular, she added, it is important to recognize that “normal” or “typical” is not always the goal, and failure to recognize that fact will make it difficult to realize the promise of precision medicine.

REACTIONS TO THE PRESENTATIONS3

Dillaha responded to the two presentations by noting that they both highlighted the need for clear and concise communication with the public.

___________________

3 This section is based on the comments by Jennifer Dillaha, the medical director for immunizations and medical advisor for health literacy and communication at the Arkansas Department of Health, and Carla Easter, the chief of the Education and Community Involvement Branch of the National Human Genome Research Institute, and the statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

Hickey’s presentation, she said, spoke to the need for health care workers to adapt their communications to meet the needs of the patient and raised the possibility that members of the health care or PMI team could serve as interpreters for difficult concepts and jargon. Hickey highlighted the importance of asking explicitly what new information means to the patient, to which Dillaha added that the same question needs to be asked explicitly for clinicians. In both cases, Dillaha said, it is important to support developing competencies in training and to provide health-literate resources and tools for health care professionals and the public. The challenge, she said, is to enable the health system and researchers to interface effectively with the public and provide the public with the skills and capacity to interface with the health system and research enterprise. These are two sides of the coin of health literacy, Dillaha said, and both sides needs to be addressed.

She continued by saying that if the health literacy community has learned anything over the past decade, it is that people in health care systems often have the wrong idea about how much the general public understands. In other words, people in the health care often overestimate how well the people they serve understand the information given to them. “This means that the people involved in the PMI need to care deeply about whether people understand what they are trying to do and to take appropriate action to confirm understanding,” Dillaha said. If that does not happen, the risk is that it will be impossible to establish the fundamental foundation of trust and understanding that Michael Wolf discussed in his presentation. Without trust, the public will react negatively, she said, and the results will be on display across social media.

Carla Easter remarked that though it has been a decade since the Human Genome Project was completed and the move into precision medicine has already begun, there is still a need to develop competencies in genomics among practitioners. She supported Hickey’s idea to work with professional organizations to develop those competencies, which the Human Genome Project did not do effectively, and to think hard about what the public wants to know about the ethical aspects of precision medicine. In particular, Easter stressed the importance of engaging communities and easing their concerns that precision medicine is the new eugenics or a means of singling out individuals as being different from the community. “We tend not to think much about this as scientists,” she said, “but for some communities this is very much in the forefront.”

Easter said she strongly supported the idea of using social media not only as a means of communicating information and building support for the PMI, but also as a means of recruitment to the PMI Cohort. She said she thought social media would be a great way to reach adolescents and even younger Americans in order to help them both understand the initiative and engage in conversation about it. As an avid Twitter user, she said,

she has witnessed many social movements getting their start on Twitter, including the Black Lives Matter movement. “If you want to reach diverse communities,” she said, “you need to think about the platforms they are on and how we can think about using social media as a way to reach out to those communities.”

While most of the thinking about precision medicine has focused on actionable disorders, Easter noted that Gunter’s presentation raised important questions about how precision medicine fits with behavioral and mental health issues and the possibility that it could lead to marginalizing individuals with certain disorders. Easter also questioned if there are things the PMI could learn from other large initiatives, such as the ongoing BRAIN initiative, about using social media and other avenues to connect with multiple audiences and communities.

DISCUSSION

Catina O’Leary started the discussion by pointing out that there is difference between writing a research paper and sending out thoughtful tweets and perhaps responding to tweets in a thoughtful, productive manner. She then asked Gunter if there are ways for the research and clinical communities to learn the skills for using these new media productively and to be comfortable when communicating out from under the institutional protective umbrella associated with more traditional forms of communication through journals and via press officers. For those who do not use Twitter, Gunter said, the first step is to sign up, follow a number of people, and then observe how they engage the Twitterverse. She noted that there are many scientists on Twitter, Francis Collins being one of them, she and Easter being two others. She also advised exercising common sense. “Do not say anything on Twitter that you would not say publicly,” she said. Gunter also said that many universities have policies regarding the use of social media as well as communication officers that will help with such use. The final point she made was that it is critical to remember who the audience is, and she noted that there are many geneticists and genomics researchers who communicate among themselves using Twitter with little interest in reaching the public, which she said she thought was fine. She also said it is important to realize that there are many members of the general public who are interested in how scientists do their job, and she cited a colleague who tweets interesting findings about individual cases in ways that do not reveal patient identity or violate patient privacy.

Linda Harris, who said she was thinking about the impact of precision medicine, asked how the health literacy and genomics communities can help parents, caregivers, and partners talk to their loved ones about the conditions they have. Hickey replied that communities and organiza-

tions are becoming more aware of this issue and the importance of the caregiver as an information conduit. One approach may be to schedule separate appointments for parents or caregivers at which they could have their questions answered. These conversations, Hickey said, will have to be individualized. Harris said she thought that perhaps social media could help by creating a platform for exchanging information when it is needed. Dillaha cautioned that the goal is to exchange factual information, and social media is not always a source of factual information.

Wilma Alvarado-Little asked the panelists for any guidance they could share on how to have a conversation with an individual who is the first person in a family to have a genomics-based diagnosis. “How can that individual be prepared to share information with other family members?” she asked. It is important, Hickey said, to recognize when a patient is in such shock that he or she shuts down. At that time, perhaps the session should be more about counseling than passing along information, and the clinician should realize that it may take multiple meetings to get across all of the information an individual and family member may need. Gunter recommended having genetic counselors involved in those conversations, particularly to help deal with the issue of family members feeling at fault. She also noted that sometimes there are more unknowns than knowns associated with a given finding. In autism, for example, there are now some 100 genes implicated to some degree with autism, but there is no answer to questions about how those genes are linked and what the implications are of having one of those linked genes.

Michael Villaire asked Easter if anyone was thinking about how to address the type of urban legend that can arise out of topics that are complex, difficult to understand, and perhaps scary to some people. He could imagine, he said, that people could worry about what researchers are doing with their biospecimens and genes and from there start thinking about genetically modified organisms and genetic manipulation. Easter replied that NHGRI has a panel of individuals from around the country and from different ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds that it has worked with to find out what members of their communities worry about and what they think about these types of issues. These conversations led over the course of 1 year to the creation of infographics that would address those types of questions. “It was very time-consuming but very important to build trust with this group so that they could provide us with true insight into their concerns and not feel as though their concerns would be unmet or that their concerns were not valuable,” Easter said. NHGRI’s approach, she said, has been to make this a grassroots effort and to find as many individuals as possible to talk with in order to allay those fears early. “I think they are now more willing to be part of the Precision Medicine Initiative because they feel as though they have a healthier idea about what it is and have a

better way of getting the information into their communities with our support,” she said.

Hickey said that her group took exactly the same approach in Manhattan’s Washington Heights community when the PMI was launched to get feedback from the community right from the start. Gunter added that although it may seem easier to spread misinformation, that notion should not keep this community from putting the right information out to the public.

Bernard Rosof had a similar question to Villaire’s in that he wanted to know how to effectively counteract misinformation. Gunter said that one approach is to “hijack” a hashtag on Twitter that is being used to spread disinformation and put factual information out to that linked audience. She cautioned, though, that it is important to recognize that there are often emotions connected with that misinformation and that one should not join a conversation on social media with the attitude that people are wrong and just do not understand the science. Be calm and let the data speak for themselves, she said, and, as an example of that philosophy, she referred to a new evidence-based guide to parenting (Haelle and Willingham, 2016) that does not take the tone of “If you do not follow this, you are wrong.” Rather, it lays out the studies and the data and lets the readers decide what the best approach is. The same authors have also written a guide to talking with one’s friends about vaccines that advocates the same approach of laying out the data. At her institution there are faculty who have family members with autism, yet they choose to vaccinate their own children and serve as an example without exercising judgment.

Easter said that NHGRI worked with the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History to create an exhibition on genomics that reached more than 3 million people in Washington, DC, and more as it has traveled around the country to places such as Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Peoria, Illinois; and Wichita, Kansas, where genomics is not something that typically shows up at the local science center. It is important to realize, Easter said, that this is a long-term endeavor and that it takes time and effort to make sure factual information overcomes misinformation. Rosof agreed and said that to overcome the fear of vaccination, the autism center at his institution had to go into the community, visiting churches and community centers and disseminating health-literate information. Using social media was not enough to get factual information into all areas of the community, he said. He said that he and his collaborators are starting a project that will look at those practitioners who achieve high rates of immunization with their patients in parts of the country where immunization rates are extremely low. His hypothesis is that communication ability and health literacy are playing a key role in achieving high rates of immunization. Gunter

said it is likely that the research will find that some of these practices simply will not take patients who will not vaccinate their children.

Terry Davis recounted her surprise when the head of the pharmacology department at her institution wrote an article for a local tabloid publication commenting on new research in addiction treatment. Gunter responded that she was an editor of a blog called Double X Science, which had the goal of writing about hard science topics at the level of the stories in magazines such as Glamour and Elle, and one of the blog entries she wrote explained the implications of the Supreme Court’s decision on BRCA1 testing. Writing for these types of publications and social media outlets requires balancing accuracy and completeness while still getting across a great deal of information, she said. Hickey said that Telemundo is a good venue for getting accurate information to the Spanish-speaking population.

Ruth Parker said that she recommends that anyone funded by or connected to the PMI should enroll in the cohort as a means of fostering communication among the research community and the public. She also said that she wonders if there are ways, such as creating a website where participants could post questions and get answers, to make two-way communication a structural piece of the PMI so that the PMI would get constant feedback on what the participants and the public really want to know, not just what the research community thinks they want to know. Hickey replied that engaging the public and advocacy groups in a more active manner, as Parker suggested, is essential. “The PMI cannot be us telling them,” she said. Advocacy groups, she added, can be valuable partners because they get engaged and stay engaged. Easter suggested that while getting input from a million people as a group is laudable, it may be more informative to get input from smaller groups that would provide more focused questions that are specific to their communities. “I think finding these small groups of people and then getting information from them is well worth the effort,” Easter said. Gunter said that allocating funds for such efforts will be crucial for enabling researchers to go into communities to have those direct contacts.

Gunter said she thought that Parker’s idea of enrolling everybody who plays a part in the PMI in the cohort was interesting given that geneticists at the 2015 meeting of the European Society of Human Genetics debated whether geneticists should get their genomes sequenced. The majority, she said, thought that they should not. The geneticists gave all sorts of reasons, many of them reasonable, including that doing so would take away resources from those who really need to have their genomes sequenced. Thus, she cautioned there may be resistance to Parker’s idea.

This page intentionally left blank.