2

Selected Issues Related to National Security Space Defense and Protection

INTRODUCTION

As noted in Chapter 1, to a greater degree than many of us realize, populations around the world, both in developed and developing areas, depend on space assets for convenience, quality of life, and resilience in the face of disaster. Satellites have brought nearly instant communication to places and people previously isolated by geography or a lack of ground-based infrastructure. Space-enabled communication has been particularly beneficial in areas of the developing world where landlines have not been laid or are unreliable, as well as to increasingly mobile populations. Data collected from space-based platforms have also brought new levels of precision to weather modeling, enabling disaster warnings that save lives.1 Space systems are used to aid in search and rescue efforts and as a source of emergency communications in disaster areas. They are critical features of the Global Positioning System (GPS) that assists navigation for commercial vessels and aircraft, and that provides the precision timing and positioning essential to managing large

___________________

1 An illustrative success story is found in the Bangladesh Flood Forecasting and Warning Centre, a group of 22 professionals in Dhaka who use National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) satellite imagery, plus mobile phone reports, to track the progress of the severe annual flooding and monsoon rains that caused so many casualties in the past. With more warning time, people have been better prepared for the onslaughts in recent years. See the Flood Forecasting and Warning Center website, http://www.ffwc.gov.bd/index.php/about-us/, for real-time maps and evidence of what a relatively small group can do.

computer networks and global financial flows, from secure wireless stock trading to automatic teller machines.

Also, to a greater degree than many Americans realize, space systems are a critical component of the national security services we now take for granted: Communication satellites, space-based imagery, positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT), and signals intelligence provide navigation and mission awareness for U.S. and allied military personnel on the ground, in the air, and at sea. They are also the backbone of the blue-force tracking that has greatly reduced casualties from friendly fire, and they underpin the cost- and collateral damage-reducing precision targeting and strike that Americans now expect of kinetic military operations. Although it certainly is possible to communicate, navigate, forecast weather, and participate in global trade without platforms in space, if deprived of them we will not do so as quickly, as well, or with as much precision as is presently the case. Loss or degradation of the information services that space systems provide would not just be inconvenient, but could generate significant hardship and endanger lives.2

Chapter 1 outlined how global space activities are rapidly changing in ways that will condition the future of commercial and security activities in and through space. Primary among these is the presumption that continued rapid technological advance and diffusion will bring about a future in which space is a domain in which the United States and many other countries, including our allies and friends as well as potential adversaries, will engage. This rough parity does not mean equivalence in national security capabilities nor will it be even across all space-related functions, but will be most pronounced in areas driven by commerce and globalization, as described in Chapter 1. This reality will inevitably necessitate a paradigm shift from one predicated on the belief that the United States would remain the undisputed leader in space, impervious to challenge by others.

As used in this chapter, “space assets” refer to more than just the satellites in orbit. Without data uplinks to fly and control the satellites and data downlinks to transfer information from space, satellites are of limited use; moreover, much of the data coming from space requires a significant amount of processing to be usable by consumers. Unless otherwise noted, therefore, “space asset” refers to the entire system comprising the physical satellite, data uplink and downlink systems, ground stations, and information processing and distribution. Space assets are characterized as providing three broad categories of information service: commu-

___________________

2 Speaking at a space policy forum, Bruce MacDonald of the United States Institute of Peace offered a useful analogy for thinking about the loss of space to U.S. military capacity as analogous to “being suddenly cut off from gasoline. We would be severely hampered” but would nevertheless remain a powerful force” (Bruce MacDonald, “The New National Space Policy: Prospects for International Cooperation and Making Space Safer for All,” remarks a Arms Control Association event, July 1, 2010, Washington, D.C.).

nications; PNT; and observation and surveillance. While the focus of this chapter is on national security space (NSS) assets, the effort focused on safeguarding these specialized assets is critical for civilian systems and users as well.

This chapter explores the requisites for protecting U.S. NSS assets in a domain crowded by state, commercial, and other interests, including transnational criminal and terror groups. It begins with a discussion of scope—namely, the nature of the space domain in U.S. security and how threats to it are characterized. A framework is then provided for evaluating space defense, which is necessary but not sufficient for space security.

THE CHARACTERIZATION OF SPACE IN NATIONAL DISCOURSE

Assessing the necessary national capabilities to defend and protect U.S. NSS assets raises a number of questions. First, what role is space intended to play in U.S. national security? Second, which uses of the space domain does the United States seek to guarantee? Finally, what specifically is the United States attempting to defend the assets from?

The Role of Space in National Security

While many in the NSS community would agree that space is no longer the sparsely populated sanctuary that it once was, debate continues as to what the U.S. national perspective on space as a domain should be and thus what role it should play in national defense. Is it a battlefield to be controlled, or solely a support environment for terrestrial military activity? Does the United States intend to fight in space or through it? Is there any lingering scope for continuing to regard space as somehow different from other geographical regions, and less susceptible to historic trends of terrestrial military competition and conflict? What can the United States do to promote and preserve, as much as possible, the legal regime of outer space as a peaceful environment for all to explore, exploit, and safeguard? More to the point, are offensive or defensive weapons, whether in space or ground-based, a requirement for protecting the’ U.S. or any nation’s inherent right of self-defense? Clearly each of these issues has implications for the design, acquisition, and deployment of space systems—activities across the Department of Defense (DoD), the Intelligence Community (IC), and other U.S. government agencies, even in the absence of clear policy guidance. The result is inevitably that design choices are made differently based on the agendas, funding constraints, and other considerations of different organizations, rather than being based on a clearly articulated set of strategic national priorities.

Why has there been a relative dearth of action and policy implementation on this issue? Scholars and practitioners involved in space activities have written

extensively on these questions, and successive administrations have recognized the topic. Clear statements on the importance of space systems and the need for what the United States would recognize as “resilience” date back to the Ford administration.3 There have been numerous high-visibility commissions such as the Rumsfeld Commission of 2001 and the Allard Commission of 2006.4 There were broad public reactions to the Chinese ASAT test of 2007. More recently, the National Space Policy of 2010 and the National Security Space Strategy of 2011 contain clear policy statements.5,6 What has not been present is a focus on achieving the stated policy goals, with resources, programs, and people devoted to the task of improving space system protection and defense.

Paradoxically, one reason for this seeming passivity may be the way Americans tend to think about space. It is fair to say that when most Americans think of space or space assets they think largely of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and conceive of space as an open and peaceful expanse for spaceflight, commercial applications, and scientific discovery. In fact, it might be argued that many Americans maintain a somewhat romanticized vision of activities in space, and, in any case, are uncomfortable with the idea of space-based weapons, even for defensive purposes.7 A national discussion updating public awareness of the changing character of the space domain simply has not yet occurred.8 In the past, there was in-depth public and professional discussion of the role and purpose of U.S. military power in domains such as the high seas and the air. There is no

___________________

3 U.S. Department of State, Office of the Historian, Foreign Relations of the United States: Volume E-3, Documents on Global Issues, 1973-1976, released December 18, 2009.

4 U.S. Department of Defense (DoD), Report of the Commission to Assess United States National Security Space Management and Organization, Pursuant to Public Law 106-65, January 11, 2001.

5 Executive Office of the President, National Space Policy of the United States of America, Washington, D.C., June 28, 2010.

6 DoD and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI), National Security Space Strategy, Washington, D.C., January 2011.

7 In a study by the Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland (CISSM), 78 percent of U.S. respondents felt that the United States should not put weapons in space even if these “could serve important military purposes such as protecting” satellites. There was also solid support (78 percent) for the United States engaging in international negotiations to prohibit attacks on another country’s satellites even if this was to gain a military advantage, and testing or deployment of ASAT weapons (79 percent) (S. Kull, J. Steinbruner, N. Gallagher, C. Ramsay, and E. Lewis, 2008, Americans and Russians on Space Weapons: A Joint Study of WorldPublicOpinion.org and the Advanced Methods of Cooperative Security Program, CISSM, January 24, 2008, http://www.worldpublicopinion.org/pipa/pdf/jan08/CISSM_Space_Jan08.rpt.pdf).

8 This was the conclusion of a CISSM report published 7 years ago in which researchers, commenting on the Bush Administration’s push for “space control,” noted that “the American public has not been engaged. In the absence of active negotiations, there has been no prominent congressional discussion of the issues involved. Press coverage of these issues has been very limited.” See Kull et al., Americans and Russians on Space Weapons, 2008.

obvious reason why space should be exempt, and, as suggested above, there are many compelling reasons to be concerned about threats to space systems.

The discrepancy between the way the American public tends to think of space and the extent of U.S. military and civilian dependence on space systems in daily life creates difficulties for national security and space policy makers and planners tasked with defending these assets. Despite doctrine that speaks to defending and defeating adversaries in space, the observation in a recent article in Aviation Week that “many senior officials shy away from using the term ‘space control’ to describe U.S. national security strategy in space as being too bellicose and sounding too much like militarization of space [for both domestic and international audience consumption]” was corroborated by a number of speakers to the committee.9 Even the way that missile defense has been framed in public discourse largely erases mention of space weapons.

There are at least two schools of thought on the value of updating U.S. public understanding of space and threats to space assets. One argues that reasoned openness in public discourse would ease barriers among elements of the U.S. bureaucracy working (and funding) space programs. The other argues that increased public discussion of space as a contested domain would be more provocative to U.S. adversaries and to the general public than any value it would provide.

The first school of thought argues that the seemingly broad gap between U.S. public perception and space security requirements is problematic in that it obstructs discussion and analysis of the practicalities of space defense, the costs and trade-offs involved, the implications of the loss of these systems and what to do, defensively and offensively, to protect them. This is not a trivial or solely political issue. It is also not an absolute: updated public education on space matters, and particularly on the types of threats to civilian and military systems that exist, does not mean that all details of U.S. space policy and capabilities are to be made public. Although it is not clear whether classification of space-related issues has led to the public’s uninformed view of threats to space assets or vice versa, many of those to whom the committee spoke made it clear that uninformed understanding of space hinders development of national security policy, military concepts of operation, tactics, techniques, and procedures, and the training of the people given the responsibility to defend assets. The lack of understanding can also confound funding and investment decisions as well as assessments of which technologies to develop. This can be a particular challenge for the U.S. military, which seeks to have public support for the policies and actions ordered by its civilian leadership. A lack of clar-

___________________

9 A. Butler, “No sanctuary, Pentagon finally puts up money to defend space assets,” Aviation Week, May 11-24, 2015. A further irony is that space has arguably been militarized from the beginning but with only sporadic experiments with “weaponization.” That may be changing as a result of recent developments.

ity even among experts on the general role that space plays in U.S. security—i.e., the foundational assumptions of space policy—inhibits development of a coherent, multiagency program to defend space systems and activities, and to establish the necessary oversight and political will to see that it is done. An issue with such significant implications for the daily lives and well-being of so many in the United States and abroad should not be derailed by public misconceptions discussed below.

A second school of thought focuses on the risk that broadening the public discussion of space security issues, especially regarding pursuit of offensive “space control” objectives, would send a provocative message to adversaries. This school tends not to believe that the national security community has been unduly hampered in the development of national security space policy by a general pattern of “softer” rhetoric. This community is well accustomed to doing its business with requisite linguistic finesse and sees value in continued reliance upon indirect and diplomatic language in U.S. public discourse about space security. Adherents of this view judge that more frank talk about U.S. national security space objectives will create more opposition, both at home and abroad, which will inhibit development of the space programs the security community seeks to advance. According to this view, public resort to blunter language about space security and offensive or active defensive capabilities would do more to provoke adverse reactions from other space actors than the good it would do in terms of facilitating coordination among U.S. space security and military decision makers. The intelligence and commercial space communities each have their own reasons for public discretion; the one wishes to protect the effectiveness of sources and methods, and the other to minimize barriers to the movement of capital and dual-use technologies in support of global markets.

One point both these schools agree on concerns the adverse consequences of over-classification of materials related to space security and protection. Of course it is essential to protect true national security secrets, but overclassification imposes costs and foregoes important benefits. Secrecy impedes robust professional debate and publication; inhibits public diplomacy; and degrades cross-domain synergies, such as between air and space programs. Unlike other crucial national security activities, such as the protection of submarine capabilities, space protection and defense activities necessarily involve the sharing of information and coordination of action with civil, commercial, and international actors. Steps are being taken to improve information sharing with allies, civil agencies, and select U.S. companies, but the process continues to be slow and difficult.

Space Services: Classifying What Is at Stake

There are numerous ways to categorize the thousands of artificial satellites in orbit today. Often this categorization is done by altitude, orbit, size, or whether they are put to commercial or military use. As technology proceeds, many of these

categories are becoming blurred. A visible example is the increased emphasis in national security space policy on military-commercial partnerships (e.g., for commercial supply of some military communications). For the purpose of considering space systems in the national security context, it may be most valuable to classify them by their use—that is, not to consider systems solely in terms of the platform or other technical details, but in terms of the types of information services they provide. This structure also facilitates assessment of the implications to national security of their loss. Following the 2006 RAND National Security Space Launch Report schema, the services provided by U.S. satellite systems are categorized into three types most important to military and national security issues: communications; PNT; and Earth observation and surveillance.10

Threats to Space Systems and Services

There are many sources of threat to space systems. Naturally occurring threats in space include meteors and fragments, as well as sun flares and other inclement space weather that can damage or destroy the satellite itself or the electronics riding on it. Ground- or air-based components of space systems are also subject to natural causes of service interruption and damage. There are also three categories of human-made threats to assets in space components. For the sake of simplicity the committee will discuss each as a threat to a system. These are (1) collision with space debris—some as small as a paint chip—that can nevertheless disrupt, damage, or destroy the components of a satellite; (2) accidental damage, jamming, or interference; and (3) intentional efforts to damage, degrade, and interfere with or destroy space systems. Threats to ground-based components and supporting infrastructure include, for example, kinetic attack against ground stations and cyber or electronic attack on communications and data networks. Viewed in this way, counter-space threats are not limited to kinetic antisatellite (ASAT) systems, but can occur at multiple nodes of the service-providing system.

Moreover, threats against different parts of these systems can have different effects, different likelihoods, and different mitigation options. While the community of space professionals is keenly aware of the full range of threats to U.S. space- and ground-based systems, there does not appear to be a comprehensive or consistent approach to categorization and risk assessment. Disambiguating different types of

___________________

10 Each of these categories can be further subdivided. For example, the RAND National Space Launch Report breaks down communications services into wideband, protected, and narrowband, with a fourth group of data-relay satellites supporting each of these; it breaks down observation satellites into those used for reconnaissance, for missile warning and defense, and for weather monitoring (F. McCartney, P.A. Wilson, L. Bien, T. Hogan, L. Lewis, C. Whitehair, D. Freeman, et al., National Security Space Launch Report, MG-503, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif., 2006, http://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG503.html, p. 2).

threats is an important first step in systematic evaluation of the status of national space assets and the capabilities needed to defend them. Without establishing a comprehensive standard, it becomes difficult to track U.S. government-wide efforts to address threats to space systems, not all of which would necessarily be accomplished by typical space community stakeholders. At present, the basis of evidence for defining a threat can vary greatly, from dated but validated threats to speculative threats based on incomplete but current intelligence.

Self-analysis is a process that is often overlooked in U.S. defense policy development and planning but that has significant implications for our capacity to protect and deter space systems. Particularly in the space domain, a better grasp by DoD, the IC, and policy makers of the international and domestic tolerances for U.S. space activities will be key to augmenting current National Security Space Policy to clarify what the United States—both the security community and the public that ultimately must support its general activities—believes is the proper role of space in national security and the stakes involved in its defense. As discussed below, only once this is done will the United States be able to use implementing directives, declaratory policy, or international agreements to clearly articulate to allies and potential adversaries alike U.S. philosophy about legitimate, safe, and productive uses of outer space, and about the responses to departures from those norms.

DEFENDING AND PROTECTING NATIONAL SECURITY SPACE ASSETS: SPACE DEFENSE TRIAD

The 2011 National Security Space Strategy calls for a “multi-layered approach to prevent and deter aggression” against space systems (Box 2-1).11

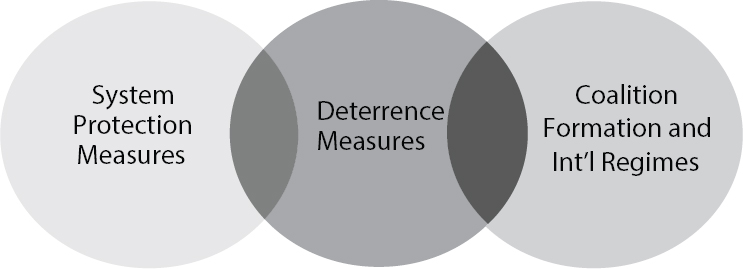

The security objectives laid out in that strategy suggest a framework of three interrelated means of defending U.S. NSS assets and guaranteeing the national security communication, observation, and PNT services that those assets provide (see Figure 2-1).12

___________________

11 DoD and ODNI, National Security Space Strategy, 2011.

12 In remarks at the Stimson Center in Washington, D.C., on September 17, 2013, Assistant Secretary of Defense Madelyn Creedon laid out a framework consisting of four mutually supporting components rather than the three described in the present report: “(1) internationalizing norms that enhance stability, (2) building coalitions for collective security, (3) increasing the resilience of our architectures, and (4) being prepared to respond to attacks against U.S. and allied space assets though not necessarily in space.” This report combines the first two into Coalition Formation and International Regimes, since they both involve discovering common interests, in the first case among allies and friends and in the second more generally and globally. Increasing the resilience of architectures is a subset of System Protection Measures, which also includes efforts to improve survivability and other attributes of space systems or deterrence. Finally, the report includes Creedon’s fourth component, Deterrence Measures. (See Assistant Secretary of Defense Madelyn Creedon, Remarks on

The first element, system protection measures, includes activities that serve the security objectives to prevent and deter aggression and defeat attacks and operate in a degraded environment. These are primarily technological solutions to enhance the survivability of space systems. The second element comprises deterrence messaging measures. The final element of the space defense triad is establishment of coalitions, and international space regimes and norms of behavior that impose

___________________

Deterrence, Stimson Center, Washington., D.C., September 2013.) http://www.defense.gov/Portals/1/features/2011/0111_nsss/docs/Stimson-Center-Deterrence-Speech.pdf.)

costs to an adversary—in terms of either having to face a coalition or in loss of diplomatic prestige or other sanctions, to prohibit activities taken against another actor’s space systems. Each of these three elements has its own attributes and limitations and no single leg is sufficient for defense; a combination of them is required to ensure a robust defense of NSS assets. Each is discussed in more detail below.

System Protection Measures

The first element of defending space systems involves primarily technical solutions for the purpose of establishing survivability of systems and “deterrence by denial.” System protection is the easiest or most straightforward of the three elements, because the United States has the greatest control over what it does and over what opportunities and challenges it presents to its adversaries. Of the three, system protection measures appear to have received the most attention and funding. As one component of a defense triad, system protection involves upgrading current systems where possible, and constructing future systems to be more survivable and thus less vulnerable to collision, interference, or attack. It also involves an array of improvements in system architecture, to make the entire satellite configuration more robust, redundant, and resilient. Improvements in system acquisition and enhancement of interoperability among systems also fit into this category.

Here the discussion highlights how protection relates to the broader issues of defense and deterrence—namely, by establishing the conditions for deterrence by denial by diminishing the probability that an attack against a space system would succeed in degrading or destroying the space services upon which the United States depends. In this sense, protective measures are a main source of deterrence by denial.13

Given the number of agencies that have stakes in space, depend on space, and are involved in high-dollar projects to protect those assets, it is critical that these agencies undertake an effort to more fully appreciate their respective interagency authorities and the larger U.S. security environment that will condition national choices and decisions in the event of a space conflict. Any response to an attack

___________________

13 This is consistent with what the DoD Deterrence Operations Joint Operating Concept (DO JOC) refers to as increasing the costs of aggression or denying its benefits. The DoD doctrine defines deterrence as preventing action by the “existence of a credible threat of unacceptable counteraction and/ or the belief that the cost of action outweighs the perceived benefits” (DoD, Dictionary of Military Terms, 2015, http://www.dtic.mil/doctrine/dod_dictionary/). More specifically, deterrence by denial attempts to forestall an attack or other unwelcome act by persuading an adversary that an attack will not succeed. For example, if the target of the attack is hidden, mobile, or well-shielded, the aggressor may not be able to find it and strike it effectively. Likewise, if the defender is capable of intercepting or disrupting the attack en route, and if the putative attacker is aware of this capability, it may conclude that the attack cannot attain its objective and may thereby be deterred from launching it.

in space will have to take into account the totality of U.S. interests, not just those directly affected by space. This approach can help to better identify and plan against those circumstances in which the country’s own processes deny it the full benefit of its capabilities by posing barriers to effective implementation of deterrence messaging or actions. Categorizing and prioritizing risks in space and creating closer whole-of-government response plans are likely to have more value than drawing redlines in space.

Efforts are under way to organize DoD space efforts as a formal major force program (MFP-12) that would provide a more integrated understanding of the resources being devoted to all defense space activities. This action should better enable the DoD to set priorities and assign resources for the protection and defense of its space assets. Doing so should also enable DoD to better coordinate with the IC, U.S. industry, and allies in protecting and defending non-DoD space assets crucial to U.S. national security. Such efforts will require more than purely technical or military capabilities, but economic, diplomatic, and political arrangements that align the interests of other space–actor nations with those of the United States. In addition to the traditional forms of deterrence, such as denial of attack objectives and fear of retaliation, U.S. security can be improved by leading space-related cooperative efforts that reduce or redirect incentives to come into conflict with the United States.

Deterrence Measures

The second leg of the space defense triad is deterrence: discouraging people, groups, or states from interfering with or attacking U.S. space systems either because there is no value in doing so or the actual or threatened cost of doing so is too high.14 It is served by both system protection measures and participation in the development of international regimes governing space. Importantly, the success of deterrence measures against attacks on U.S. space systems, like other forms of deterrence, is in the perception of the would-be attacker. It is a political and psychological strategy “that must be directed by political leaders, coordinated with diplomacy, and sensitive to the adversary’s political constraints, world views, and

___________________

14 Deterrence by threat of retaliation was at the core of the U.S.-U.S.S.R. nuclear relationship during the Cold War. Each side was deterred from launching a first strike against the other for fear of unacceptable retaliation. Much strategic thinking and weapons systems development was devoted to ensuring that, under any combination of circumstances, the ability to launch a devastating second strike was preserved, so that neither side could calculate that a first strike would be profitable. Notably, the threatened response to a hostile action need not be in kind—retaliation in a different time, place, and manner may be more effective in influencing the calculation of the adversary, because the responder can exercise freedom to reply in a manner tailored to its advantage.

perceptions.”15 As such it is not an outcome that can be induced unilaterally, but the result of an exchange or interaction between a deterrer and a deterree. As Milevski puts it, “One cannot pull deterrence out of a toolbox and employ it. It must be induced in the other.” It is the result of an adversary’s choice to be deterred.16

Effective deterrence is classically based on three principles: (1) credibility, often associated with a state’s perceived resolve or political will that a threatened response can and will be executed if a red line is crossed; (2) possession of coercive capability sufficient and appropriate to hold an adversary’s valued assets at risk, and to implement a threatened response to an unwanted action; and (3) the ability to communicate to a potential adversary what actions are to be avoided and the nature of the intended response (punishment). In each of these elements, the United States must draw upon the full array of elements of national power, including diplomatic, intelligence, military, and economic tools.

Credibility of a Deterrent Threat

The United States’ ability to deter peer, near-peer, and non-state actor efforts to interfere with or attack space systems requires that deterrent threats be credible. First, a potential attacker must believe that the defender can identify the source of an attack should one occur. An adversary that does not fear being caught has much greater latitude for action. This requires that potential adversaries believe that the United States maintains the capacity to detect, track, and identify a full range of space objects and to distinguish hostile attack from system failures, space weather, or other natural phenomena. Deterrence efforts can be rendered effectively useless by an inability to recognize whether a system has been struck or interfered with, where in the system the attack has occurred, and who did it. Under those conditions an adversary could be incentivized to strike first in any conflict (military or otherwise), especially since an effective attack on the enemy’s satellites may well degrade its ability to respond in any coordinated and effective manner. It is important to note that the issue is not just one of diagnosis and attribution however; it is timely attribution. Adversaries considering interference with U.S. space systems need not believe that they would never be found out in order for deterrence to fail, just that the interference remains undetected long enough to achieve the desired operational, tactical, or political objective.

___________________

15 J. Levy, Deterrence and coercive diplomacy: The contributions of Alexander George, Political Psychology 29(4):537-552, 2008.

16 L. Milevski, Deterring “Able Archer:” Comments arising from Adamsky’s “Lessons for Deterrence Theory and Practice,” Journal of Strategic Studies 37(6-7):1050-1065, 2014, doi:10.1080/01402390.2 014.952408.

Potential adversaries contemplating interference with U.S. space systems should expect the United States to execute any necessary and proportional response, but not necessarily in space. In considering the totality of U.S. interests in any particular conflict, the protection and defense of U.S. and allied space assets may be considered as part of continuously updated war plans of each combatant commander in their respective areas of responsibility, in coordination with the U.S. Strategic Command. Routine exercises could include a wide range of retaliatory actions across different domains to enhance the credibility of U.S. diplomatic and declaratory statements, through public and nonpublic channels.

Capability of Responding

Because they are so crucial to the credibility of deterrent messages, rapid and accurate diagnosis of an attack wherever it might occur across the entirety of a space system and identification of its source are among the most essential capabilities for space defense and protection. They are appropriately prioritized in U.S. National Space Policy and directives regarding space situational awareness (SSA). What is not clear is the extent to which the priority for enhanced awareness is also applied to terrestrial aspects of space systems. Finally, it is important that these efforts are managed carefully with progress milestones and effectiveness measurement. This should occur not only on the technical side. SSA requirements and capability should not just feature space security policy but should also find their place in national security policy and implementing plans.

Additional requirements for the credibility of deterrence messages are that potential adversaries believe that the deterrer has both the capability and the will to respond to an attack once identified. It is not difficult to argue that U.S. defense forces could respond forcefully to deterrence failure in any number of ways. The United States can respond. However, the credibility conundrum, often cited with regard to nuclear weapons, is the believability that the United States will respond in circumstances short of catastrophic damage or loss of conventional capacity. The nature and scale if not the details of response to all-out, strategic attack on the homeland are fairly easy to imagine. However, if that attack were to avoid immediate loss of life, for example, what would be an appropriate level of response? Is limited attack that disables mission critical space service in an area of operations during a crisis more or less escalatory than total destruction of a global observation system in peacetime? Given that the fundamental value of almost all current U.S. space systems comes from the information they provide, there are potentially useful analogies to be drawn with cyber-related attacks and responses. The purpose of an intentional attack is not merely to disrupt or destroy the function of a space or cyber capability, but by doing so, to achieve some political or military

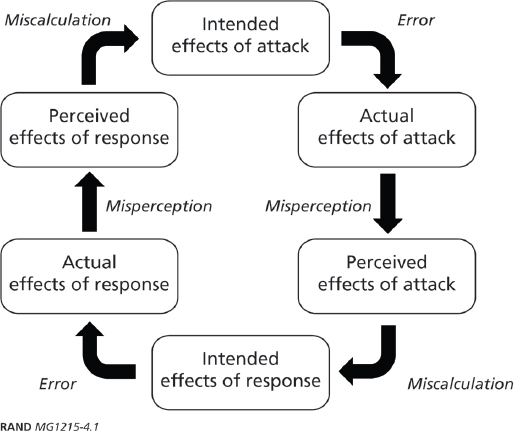

end. Figure 2-2 is derived from a RAND report on responding to cyberattacks of various kinds, including the problem of attribution.

It is important to stress here the possibilities for cross-domain deterrence. That is, a threat to a space system need not be countered exclusively, or even mainly, in space. In appropriate circumstances, a response targeting an enemy’s ground, sea or air systems might be more effective than retaliation in kind. Especially when the United States is so much more invested in space—receiving so much benefit from its satellites and accordingly becoming so much more dependent upon them—artificially confining a confrontation to space may work sharply to our disadvantage. It is critical to maintain flexibility in our deterrent posture, to be able to respond to a threat to NSS assets at a time, place, and manner of our choosing.

In responding to attacks on cyber and space systems, it is helpful to understand the many sources of uncertainty for adversaries in mounting an attack and for the United States in responding to one. At a technical level, there can be difference between what the attack intended and what it achieved (what we term here as “error”). At the assessment level, there can be differences between the actual effect of the attack and how the attack is perceived by both the attacker and the defender (what we term here as “misperception”). Misperception can be due to both technical and nontechnical issues, such as inadequate SSA or poor political understanding of an adversary’s motives. Finally, in responding to an attack, whether in a symmetrical or asymmetrical manner, the actual and perceived effects of the responses may be assessed differently by the adversaries (what is termed “miscalculation). There may be a technical aspect to miscalculations, such as inadequate intelligence or understanding of an adversary’s vulnerabilities, but the primary challenge will be lack of understanding of an adversary’s motives and values—an understanding that is also necessary to the effective creation of deterrence in the adversary’s mind. Reducing the sources of error in the decision cycle for responding to space attacks requires capabilities that also improve the resilience of space systems. Some of these needed capabilities are technical (e.g., models of adversary satellites and communications systems) while others require better insight into adversary thinking and a better understanding of what is important to the United States and its allies. The last point goes beyond an understanding of an adversary’s doctrine, organization, and war plans, but calls for insight into what the adversary desires and fears. This allows for a better understanding of an adversary’s internal political calculations, so as to better tailor U.S. deterrence capabilities and actions.

Communicating Deterrence Messages

What is the deterrence objective with regard to space assets that the United States seeks to communicate? U.S. policy statements, and indeed strategy, are still developing and at present remain somewhat ambiguous on this point, although

sometimes a degree of studied ambiguity can be a useful component of a deterrence strategy. It is relatively clear that the broad goal is to deter others from attempting to interfere with, deny, degrade or destroy the space services (e.g., satellite-based communication, satellite-based sensors, and positioning, navigation, and timing) that the United States uses during peacetime, crisis, and war. The committee has described what the objective and threat might be. Deciding on and communicating response options also requires a good understanding of why a potential adversary might act. Classical deterrence theory often takes the “why” out of consideration because it assumes both aggression and the means of mitigation—namely, when rule violations and aggression occur, costs can be lower than gains when actors do not fear retaliation. Applied in the security context of the Cold War, costs were generally taken to be the loss of some military capacity or valued target by kinetic means. In a few instances costs could also be induced by international sanctions for violations of established norms. However, as evidenced by U.S. counterterror efforts over nearly two decades, eliciting a destructive or violent response for other than battlefield effect can be an adversary’s objective. The point is, it is essential for national security decision makers to consider the “why” of adversary behavior when deterrent threats and possible responses to deterrence failure are developed.

This is the impetus behind’a pivotal article on tailoring U.S. deterrence activities to 21st century adversaries.17 It is no less the case in the space domain.

To date, most discussion of which actors might threaten NSS assets and thus to whom U.S. deterrent messages should be accessible focuses on states. In particular, China and Russia might view the ability to deny the United States use of space as an important means of deterring U.S. conventional military operations, and as a force multiplier in the case that their deterrence efforts fail and they finds themselves in a military conflict with the United States. However, looking forward, the list of potential adversaries with incentives to degrade or destroy U.S. NSS assets does not, and will not, end with China and Russia. As a recent Foreign Affairs article points out, with rapid advances in microcomputing as well as lower costs of commercial launch and ready-made satellites, new types of actors will without doubt be entering the space-faring community.18 While most will be research- or commerce-oriented, it is also the case that many more than those we now consider space threats will soon enter the fray. As for threats to U.S. national security, these could include non-state actors with aggressive intentions; criminal organizations; and even the commercial entities that U.S. policy makers look to in order to stem the cost of a fully government-funded space program. As technology progresses, proliferates and inevitably becomes less costly, a critical feature of the defense strategies possessed by even non-space-faring actors will include denying the use of space to militarily superior foes, so as to remove space as a source of strategic advantage.

Regarding some of the smaller space powers, the two types of deterrence discussed above will still be operating, but perhaps with somewhat different effect. For example, deterrence by denial might be somewhat easier, if emerging space players will at least initially be capable of launching only relatively less sophisticated (and less numerous) attacks on U.S. satellites; however, even unsophisticated attacks might be quite devastating to an insufficiently resilient satellite system. Deterrence by threat of U.S. retaliation would likely continue to be robust, as the United States would likely have multiple avenues for counterattacking the aggressor state, but it would likely need to be an asymmetric attack, because the new space powers would probably not be so dependent upon their own satellite services that U.S. disruption would be equally important to them.

___________________

17 M.E. Bunn, “Can Deterrence Be Tailored?” Strategic Forum, National Defense University, No. 225, January 2007.

18 D. Baiocchi and W. Welser IV, The Democratization of Space, Foreign Affairs, May-June 2015.

Coalition Formation and International Regimes

The third leg of the deterrence triad focuses on the advantages of enlisting additional participants and the possibility of enhancing the security of U.S. space programs and activities by leveraging international coalitions and regimes. As noted, the United States space security actors enjoy partnerships with a wide array of players: commercial operations in the United States and elsewhere; multiple friendly states with substantial interests in peaceful operations in space that parallel our own; nongovernmental organizations, and others. These diverse capabilities support deterrence by providing multiple redundant pathways for the performance of vital space services, reducing the vulnerability of the United States. By generating less dependency upon any single space vehicle or network, these coalitions can diminish an adversary’s expectations that an attack on any one, or a few, satellite nodes could effectively deny space services.

International actors can also contribute to deterrence by raising the political price of hostile space actions, by giving more players a direct stake in avoiding hostilities, and by creating more opportunity for pressuring the hostile actors to avoid arousing the entire community. International law, through the creation and advancement of legally binding treaties and other meaningful norms of behavior, can contribute to this form of deterrence as well. No new agreements of this sort have been concluded for several decades, and none seems immediately on the horizon. The United States has not taken advantage of the opportunity to lead the world in the consideration of additional possibly useful norms here.

Outer space, like other areas of international relations, has seen its share of arms racing. Many factors contribute to a country’s decisions about pursuing space weapons, but one of them undoubtedly is the actions of its erstwhile rivals. In an arms race, it can be unclear who started it and it who is ahead may also be debatable. Self-restraint at any point by any one country, including the United States, may not be effective in dampening down an emerging space arms race. But it does seem likely that if the United States pioneers a new development in space weaponry, other actors are likely to follow, more or less, sooner or later. However, since the United States depends on its NSS assets more than any other country, it has a big stake in promoting the security and sustainability of the space environment, and thus a strong interest in avoiding a space arms race—even if it were an arms race that the United States could, in some sense, win owing to its technological advantages.

In responding to the recent space weapons activities of other countries, therefore, the United States must be attentive to the long run—not just whether it can effectively outdo the most recent actions of China and Russia, but how those states will later counterrespond to our moves, and what cycle of competition may ensue. The premium, accordingly, should be on measures to negate or mitigate, to the extent possible, the weapons advances made by Russia and China, without

stimulating them to proceed even further and faster in a direction that is distinctly disadvantageous to the United States.

Exercises that include groups from across the DoD, IC and combatant commands as well as participation from the Department of State and other interested space stakeholders offer both practical training and opportunities for deterrence messaging. Including domestic security and public resilience services in the simulation of emergency situations enhances these opportunities. Exercising the loss of systems including cross-service, emergency management and response, and public resiliency is one way to enhance the U.S. deterrence message by reducing the possible effect of space attacks. U.S. space policy cannot intelligently be made without regard for the policies and practices of other states, and without attention to the likely interaction between our choices and theirs. Indeed, the United States does not unilaterally decide questions about the future security of outer space: We surely have a voice—arguably the most important single voice—on those matters, but many stakeholders will participate, and will respond to our words and their own interpretations of our actions. Finally, the fact that the United States is unlikely to be fighting alone against peer or near-peer adversaries is important when it considers appropriate space security strategies. The United States is inextricably linked and dependent upon its allies to fight with it—something that was well recognized by the establishment of interoperability standards—for example, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization standardization agreements (STANAGS) and common field training venues. Extending this paradigm to the space domain is critical for overall net resilience.

FINAL THOUGHTS

The purpose of this chapter has been to discuss the requisites for the nonmaterial aspects of the defense and protection of U.S. NSS assets. The importance of these assets to the safety and quality of life for people around the world and here at home is commonly underappreciated. However, there exists an opportunity today for the relatively small NSS community to engage the Congress and the public in a national discussion about the threat to U.S. NSS assets, the U.S. role in space, and the types of activities the United States should be engaging in. Opening up the public discussion on what has fast become the new normal in space—an environment that is crowded with debris and one that international actors may seek to use for aggressive purposes—would educate the public about the threats to aspects of daily life often taken for granted. Within the limits of security classification and with sensitivity for how the discussion may be received abroad, a new openness could also facilitate discussion of what it will take in the current circumstances to defend U.S. and global space assets from man-made efforts to degrade or defeat them.