4

Children with Serious Medical Conditions and the Behavioral Health Implications

Serious medical conditions have many implications for the behavioral health of children with those conditions and for their families and caregivers. As such, consideration of these conditions involves many of the broad themes discussed at the workshop, including a two-generational approach toward children and their families, the need for measures of health and well-being, and the benefits of working simultaneously across disciplines and conditions.

A panel of four speakers at the workshop considered the intersections between medical conditions and behavioral health. Two of the speakers looked at specific conditions—medical traumatic stress and asthma, which should be considered “as exemplars,” according to the panel’s moderator, Mary Ann McCabe of the George Washington University School of Medicine and George Mason University, “since the lesson [from these examples] would hold true for diverse conditions.” The other two speakers looked more broadly at issues of social integration and care coordination for children with complex health needs.

PEDIATRIC MEDICAL TRAUMATIC STRESS AND ITS IMPACT ON FAMILIES

When children have a serious illness or condition, they tend to have developmentally shaped, emotional reactions such as anxiety, depression, or behavior problems, explained Anne Kazak, codirector of the Nemours Center for Healthcare Delivery Science, codirector of the Center for Pediatric Traumatic Stress at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and A.I. duPont

Hospital for Children in Delaware, and professor of pediatrics at the Sidney Kimmel Medical School of Thomas Jefferson University. Mothers, fathers, and other caregivers, along with siblings and other family members, also can have a range of reactions, including traumatic stress responses. Preillness functioning tends to predict longer-term outcomes, Kazak noted, and social isolation is a predictor of worse outcomes. The majority of children and families are resilient, but many have psychosocial concerns that can affect the course of treatment.

Kazak focused on traumatic stress responses, which she described as a set of multiple psychological and physiological responses of children and their families to pain, injury, medical procedures, and invasive or frightening treatment experiences. Many aspects of illness and injury are stressful, but some are potentially traumatic, and traumatic stress and associated emotional reactions can have effects that seriously impair a child’s or family member’s functioning.

Traumatic stress is marked by symptoms that result in distress and may impair certain aspects of functioning, such as re-experiencing, arousal, and avoidance. It differs from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) by focusing on the symptoms, whereas PTSD is a diagnosis of psychopathology.

Medical events can lead to traumatic stress in a number of ways. They can challenge beliefs about the world being a safe place. They can create a realistic or subjective sense that a child could die. Medical treatments can be frightening. “When we work in medical settings, we sometimes forget how overwhelming and stressful all the high-tech intense medical treatments and equipment can be,” Kazak said. A child or family member may feel helpless or uncertain about the course or outcome of an illness or condition. Treatment can cause pain, the observation of pain in others, and exposure to other children who have died. Finally, people have to make important treatment decisions at times of great distress.

Four meta-analyses have uncovered several risk factors for PTSD after acute trauma with medium and large effect sizes, including subjective life threat; acute post-traumatic stress in children or adults; depression and anxiety in children; low social support; and maladaptive coping strategies, such as social withdrawal, avoidance, or thought suppression (Alisic, 2011; Cox et al., 2008; Kahana et al., 2006; Trickey et al., 2012). With childhood cancer, evidence of PTSD or post-traumatic stress symptoms is very common at diagnosis and during early treatment, with 40 to 50 percent of parents qualifying for acute stress disorder. This continues during long-term survival, with the mothers and fathers of childhood cancer survivors having elevated rates of post-traumatic stress symptoms compared with controls (Kazak et al., 2004). Nearly all families have at least one member who meets one of the diagnostic criteria for PTSD, Kazak said.

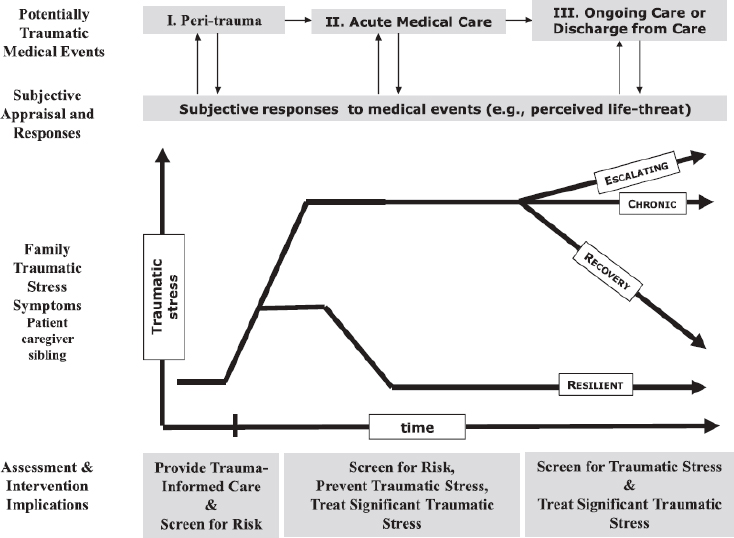

The normal course of reaction to a traumatic medical experience is that

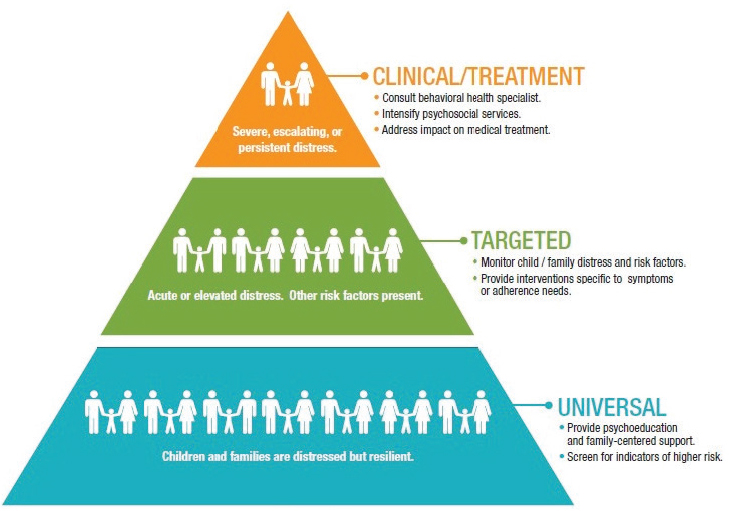

the stress goes up and then plateaus before beginning to decline, become chronic, or even increase (see Figure 4-1). But for some resilient families, stress plateaus at a lower level and begins to decline more quickly than for the average family. These resilient families may need less targeted or clinical treatment and may be well served by universal treatments that provide education and family-oriented support (see Figure 4-2).

Kazak and her colleagues have developed the psychosocial assessment tool (PAT) that can be used to screen a family for psychosocial risk (www.psychosocialassessmenttool.org). Available in a variety of languages, it has been used in research and clinical care at 77 U.S. sites in 33 states since 2007 and in 30 international sites. The screening tool does immediate risk scoring and generates family-centered reports to support decision making and communication. For example, across 6,500 administrations of the PAT, 55 percent of families were determined to need only universal supports, while 34 percent were determined to need targeted interventions and 11 percent were deemed to need clinical treatment.

SOURCE: Price et al. (2016). Reprinted with permission from Oxford University Press.

SOURCE: Reproduced with permission from the Center for Pediatric Traumatic Stress (CPTS) at Nemours Children’s Health System ©2011. All rights reserved. The PPPHM may not be reproduced in any form for any purpose without the express written permission of CPTS. To obtain permission to use the PPPHM, contact Anne Kazak at anne.kazak@nemours.org.

Kazak and her colleagues also have been working to develop better ways of assessing the strengths and trajectories of families. Children live and interact in families or other systems, and these systems influence every aspect of their lives, she pointed out. Families are the key to participatory research, patient engagement, and outcomes.

Kazak also noted that they have developed an intervention model that integrates behavioral therapy and work with families around symptoms of traumatic stress. People are being trained in the model, and the use of technology is being considered for greater integration. Additional models exist that would make it possible to do larger studies across different systems.

The PAT has been adapted for different groups, though it is still an instrument under development, Kazak noted. Some people have used it clinically as well as in research, but it is only a screening tool, and additional procedures are needed to follow through and offer families and other groups the right care.

The Website for the Center for Pediatric Traumatic Stress, which is part of the National Child Traumatic Stress Network, provides a health care toolbox that helps children and families cope with illnesses and injuries (see https://www.healthcaretoolbox.org [September 2016]). After the ABCs of medical care are addressed (a traditional mnemonic referring to airway, breathing, and circulation), providers need to think about the DEFs (distress, emotional support, and family). The DEFs of trauma-informed care, said Kazak, are reduce distress, provide emotional support, and remember the family. The site has abundant resources and connections to training programs for health care providers, including nurses. As the Website points out: “You are not alone: Child life, social work, and psychology departments at your hospital can help. You are not helpless: Research shows that dealing with the stress of this experience now can minimize PTSD for everyone in the future.”

MANAGING ASTHMA

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways, and it is a major public health concern for pediatric populations. It causes 14 million missed days of school annually, and 13.5 percent of all pediatric hospitalizations are for asthma (Denlinger et al., 2007; Moorman et al., 2011; Akinbami et al., 2012).

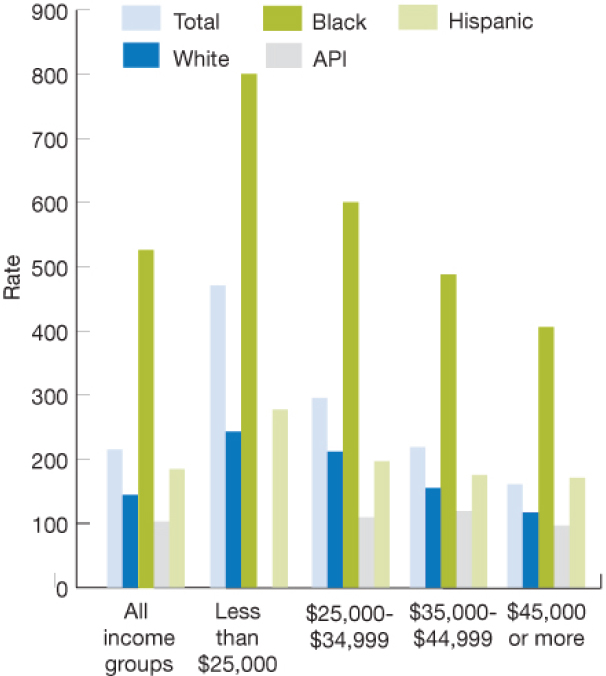

Asthma is not curable but it is manageable, said Robin Everhart, assistant professor of psychology at Virginia Commonwealth University. However, families can be hard-pressed to minimize exposure to asthma triggers, recognize symptoms, and manage medications. Pediatric asthma also occurs at very different rates in different population groups. It is higher among African American and lower-income groups than in other racial, ethnic, and income groups (see Figure 4-3). These pediatric asthma disparities are “multidetermined,” with several domains that overlap and help to predict the occurrence of disparities (Canino et al., 2006). In the domain of individual characteristics, inherent factors include genetic and biological factors, while modifiable factors include beliefs about asthma and medications, illness management, and psychological stress within families, such as stressors related to living in poverty. In the domain of environmental and contextual factors, indoor allergens, outdoor allergens, pollution, and environmental stresses all influence pediatric asthma disparities. Within the health care system, insurance coverage and reimbursement practices affect asthma disparities, as do such factors of the system as provider cultural sensitivity, workforce diversity, the use of evidence-based care, workload, and available resources. Finally, the provider’s characteristics can have an effect, including race and ethnicity, training, and beliefs and stereotyping in the provider-patient interactions. “We hear a lot from kids that maybe

NOTE: Rates are shown as the median income of the zip code of residences. API = Asian-Pacific Islander.

SOURCE: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2005).

they don’t trust their provider, or there’s something about the way that their provider interacts with them that makes them not want to talk,” she said.

Everhart’s work is centered on Richmond, Virginia, which “is one of the most challenging places to live if you have asthma,” she said. The pediatric asthma hospitalization rate in Richmond is more than twice the overall Virginia average. Many families live in poverty, and environmental pollution is a factor. Though many families are resilient and are succeeding, others struggle to handle preventive and acute symptom management.

Everhart has used two broad approaches to the development and refinement of interventions. One, known as ecological momentary assessment (EMA), uses smartphones to survey parents regularly over the course of a

day on such factors as sleep, asthma symptoms, and neighborhood stress. EMA reduces recall bias, since parents are remembering what has happened in the past few hours rather than the past few weeks. “Using EMA, we’re hopefully able to get a better picture, an accurate representation, of what’s happening on the family’s end,” she said. The second approach is a community-based needs assessment, which gathers information from caregivers, children, schools, and other stakeholders to develop a program to help children with asthma.

The Childhood Asthma in Richmond Families Study looked at children with persistent asthma and their caregivers in 61 families. Ninety percent were African American, 55 percent had yearly incomes below $19,000, and 82 percent of children had one or more emergency department visits in the previous year. Using EMA, the study found that on days when caregivers reported feeling less comfortable in their neighborhoods or less able to control child asthma at home, they reported more daily asthma symptoms in the children. “There may be violence in the community, there may be some safety concerns,” said Everhart. “Oftentimes, cognitive and emotional resources are spent on some of those safety concerns at the expense of more disease-related management behavior.”

The Asthma in the Richmond Community (ARC) project had the goal of conducting a community-based needs assessment to inform the development of a randomized clinical trial to decrease asthma morbidity among urban children ages 5 to 17. It allowed Everhart and her colleagues to meet with stakeholders, run focus groups, and learn from the community about what families need and how evidence-based interventions can be adapted for those families. A caregiver and youth advisory group consisting of three parents and three children with asthma met with the research team monthly to bring a community perspective to such instruments as focus group scripts and community surveys. In addition, a group of community residents were trained in data collection so that they are able to analyze data.

Themes emerging from the focus groups have centered on visits to the emergency department, insurance coverage for asthma medications, adherence to daily controller medications, and other people understanding the seriousness of asthma. For example, the focus groups have revealed that visits to the emergency department are not as stressful for children and families as is generally presumed. “There are some real reasons why some families are choosing to access the emergency room,” said Everhart, which requires rethinking some of the existing strategies around asthma management. Similarly, the focus groups have revealed why adherence rates are not as high as would be expected. She explained, “Families understand the need to take a daily controller medication yet they’re not able to, and we’re working with them on why that might be.” Regarding the seriousness of asthma, some teachers might not appreciate that wearing strong perfume is

harmful, or students might not appreciate that smoking around classmates with asthma can worsen their condition.

Everhart concluded with several take-home messages. A child’s community, including its strengths and weaknesses, needs to be taken into account, she said. In addition, a focus on families is important, including caregiver health and psychological well-being. Finally, meeting the needs of the family is critical: “What is it that you need, and how could we help you?”

INCLUSION TRAINING FOR PROGRAMS THAT SERVE CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES

Torrie Dunlap, chief executive officer of Kids Included Together (KIT), was a drama teacher who expected to spend her life teaching children tap dance and musical numbers. As she recounted, when she was the education director at a youth theater company, a mother called and told her that she would like her child with Down syndrome to be in an acting class. “As a 22-year-old with no prior experience with disability, I kind of panicked. I didn’t know what to say to her,” she recalled. “I was afraid. I didn’t think I could do it. I didn’t know what an acting class with a child with Down syndrome could look like.” She asked the mother for help and was referred to KIT, a nonprofit organization that works to facilitate inclusion for children with all types of disabilities. “That experience changed my life,” Dunlap said. “It also changed the theater company where I worked. It was a transformational experience for all of us. We began to get good at this and began to include children with a wide range of disabilities, including very significant disabilities, in theater programs. We were all fundamentally changed by the experience of having children with disabilities in our programs.”

After several years working with KIT as a client, Dunlap was hired as a part-time program coordinator, funded by a small grant in 2003. KIT was founded in 1997 when a woman who had polio left a large bequest to the Jewish Community Foundation in San Diego so that children with disabilities would be better served in the community. The foundation also hired a woman named Gayle Slate, the mother of a child with cerebral palsy who had experienced considerable exclusion, who was committed to including children with disabilities in their communities. Beginning with an inclusive summer camp, KIT evolved to have the mission of teaching inclusive practices to organizations that serve children.

The organization’s goals are rooted in the Americans with Disabilities Act, “but we are not the ADA police,” said Dunlap. “We do not go in and tell people what they’re doing wrong, or at least we say it nicely if we do.” Its vision is a world where inclusion is the norm, not the exception, and it acts as a friendly and helpful guide on the path to inclusion. Its goals are to change the way people think about disability and make sure that

every place where children want to go in a community is prepared to meet their diverse needs. As Dunlap said, a specific diagnosis is less helpful than information on how the program can support the child’s individual needs.

KIT uses a blended learning model, including live and online training, to teach and build capacity in child and community-based programs like preschools, summer camps, afterschool programs, sports leagues, and scouting. A team of highly skilled trainers delivers in-person training and classroom consultation. KIT offers access to on-demand online information and operates a call center staffed by inclusion specialists. “Teachers can call when they have a problem and say, ‘A mom is coming in tomorrow. I don’t know what to say.’ ‘A child in my class did this, and I didn’t know what to do,’” Dunlap explained. KIT tries hard to find the “early adopters,” people who might not have much experience or knowledge but are interested and curious. These individuals become “foot soldiers” for the organization because they bring the rest of an organization and other organizations along. “The unit of change is the people, because the organization is very hard to change,” she said.

The 2011 World Report on Disability (World Health Organization and World Bank, 2011) stated, “Children with disabilities are among the world’s most marginalized and excluded children.” As Dunlap said, society places a huge stigma on families who have children with disabilities, which makes it difficult for many families to access community-based supports, especially families with limited incomes and resources. Research has shown that inclusion of children with disabilities in an activity has benefits for everyone, including measurable gains in social skills, academic development, communication, confidence, autonomy, and even test scores (Division for Early Childhood and National Association for the Education of Young Children, 2009).

In accord with KIT’s theory of change, people who learn to include children with disabilities become advocates for those children in their communities and take more of a leadership role. They teach others to see disability as a difference and not a deficit. When people adopt a strengths-based model, “they accept disability as a natural part of human existence,” Dunlap said. “They begin to see [the] barriers that we’ve created, and they figure out how to knock down those barriers to participation.”

KIT also asks providers to see what children can do to realize their potential and to hold all children to much higher expectations. “Low expectations is a huge problem in our field, which is why we have a dropout rate for students with disabilities that is two times higher than for students without disabilities,” according to Dunlap. During the training process, providers have opportunities to reflect on their unconscious biases, which can help shift their mindset. “This is often a very powerful experience for the people that we teach,” she observed.

Each individual taught by KIT can reach an average of 17 children per year, or 300 children over the course of their career. They also can influence other providers by mentoring and coaching their peers and colleagues. With 300 program sites served in San Diego County, 220 national programs currently being served, 49 programs being served internationally, and 22,620 learners, KIT has the potential to reach more than 380,000 children. “That looks impressive, but I tell you it’s really not,” said Dunlap. “The need is so much greater. We are working to scale our organization to be able to serve many, many more people.”

KIT also advocates for children with disabilities. It was involved in a recent policy brief on the inclusion of children with disabilities in high-quality early childhood programs. KIT is a special consultant to the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations and does training for military child and youth programs on 245 military bases around the world. It works with the U.S. Department of Education, the federally funded 21st Century Community Learning Centers programs, YMCAs, Boys and Girls Clubs, 4H Programs, and Girl Scouts. “When providers have the training and support that they need, they are capable of meeting the needs of children with diverse abilities,” said Dunlap.

IMPROVING SERVICE DELIVERY FOR FAMILIES OF CHILDREN WITH COMPLEX MEDICAL NEEDS

In its report Children’s Health: The Nation’s Wealth, a National Research Council and Institute of Medicine committee stated that, “Children’s health should be defined as the extent to which an individual child or groups of children are able or enabled to (a) develop and realize their potential; (b) satisfy their needs; and (c) develop the capacities that allow them to interact successfully with their biological, physical, and social environments” (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2004). This definition is much broader than what is used in health care systems today, said Amy Houtrow, associate professor and vice chair in the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation for Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. “I want us to use that frame when we talk about medical complexity,” she said.

Contextualizing the lives of children includes considering their experiences with poverty, adverse childhood experiences that might be multigenerational, their ability to function in schools and in the community, and the resources to which they have access in their communities. In addition, they might have experiences with the foster care system, the juvenile justice system, or law enforcement. “If your teenager is one who frequently elopes because they have autism, it might be the police officer or your good

neighbor who’s your first responder—not necessarily the emergency room,” said Houtrow.

As the health care system is refined, revised, and transformed, different families will have different needs, but there are some consistent themes, said Houtrow. Families want simple and straightforward access to needed services. They do not want to spend a lot of money out of pocket. Families who have children with complex needs often suffer from work loss and limited social engagement and opportunities. The health care system needs to focus on these broader disadvantages, not just on biomedical metrics that can be measured, Houtrow insisted. “Families are concerned about whether they’ll keep their job because they came in late again because they had to take care of their child,” she said. “They might not have a home next month. Some of these basic necessities need to rise to the forefront when we think about transformational change in the health care system.”

As with families, one-size solutions do not fit all children. A 15-minute appointment in a pediatrician’s office is not going to be sufficient for a child with complex needs, Houtrow observed. Families may not be able to get time off to go to the doctor. It can be very difficult simply to make an appointment by phone. Other ways of accessing 15 minutes of information or advice, such as telemedicine or a home visit, might have a greater impact on a child and family than an office visit, yet the health care delivery system is not pliable enough to successfully offer these types of services.

Systems of care consist of groups of related parts that either work well together or do not work well together, said Houtrow. Some of these parts are in the health care system, such as clinics and hospitals, but others are not, such as schools and other community resources. Today, different care systems do not necessarily talk or work with each other, she continued, noting “sometimes they’re in opposition with each other, and sometimes there are limitations on how you can access them.”

As Houtrow put it, an important aspect of promoting health and well-being is having disparate care systems “become good neighbors.” That requires being coordinated within systems and among systems, which requires communication. Today, many physicians still send and receive information by fax machines, and medical record systems do not necessarily communicate with each other, much less with schools or other community resources. She noted

As a pediatric rehabilitation medicine provider, I see my primary job as living solidly in a healthy neighborhood that makes connectivity happen. I can’t speak enough to the value of being able to do clinics in a school with the physical therapist, occupational therapist, teacher, and speech therapist for a child with disabilities. I get to hear what’s happening every day by the people who get to do it every day. . . . When we think about delivering

high-quality care, we have to potentially be breaking down walls—those walls can be barriers that don’t allow us to communicate by phone or electronically, or they can be actual physical walls.

Team-based care for children with complex conditions can be multicoordinated, intercoordinated, or transcoordinated. In the first, many disciplines are working together in the same setting at the same time, though they have different goals. In the second, communication about goals allows team members to work together toward common goals. In the third, disciplinary boundaries are blurred to better achieve shared goals and produce synergies. In transdisciplinary team-based care, “sharing goals, at the knuckles of the intersection between disciplines, is often the best way to keep the ball in the air,” said Houtrow.

Part of team-based care is care coordination. In a complex health care system, care coordination involves having someone who knows about what a child’s needs are, knows what a family’s lived experience is, knows what challenges they face, and helps access aspects of care in the health care system and outside of it. The center of team-based care and care coordination remains the child and family, but the dynamic nature of childhood and social life is taken into account in improving systems of care, said Houtrow. From this perspective, the important question is whether children are able to participate in day-to-day life in the way that they want to, “being happy, healthy, and well,” said Houtrow. Thinking about the whole child requires cutting across disciplines and breaking down silos.

The detailed structure of a care team also can differ. For example, a pediatrician may provide a medical home for a child with a disability, but when pediatricians are faced with health care needs that exceed their capability to manage, they may turn to a comanagement strategy where a subspecialty group takes the lead along with a pediatrician. Another model is where specialty clinics act solely as consultants but do not take over the management of care. A care manager can be in a primary care setting or a tertiary care setting.

A medical home model is especially attractive because it can optimize services for children, especially if services are collocated, with behavioral health services, legal services, and social services nearby. In this mode, a general pediatrician can be the coach or leader of a team that includes many different providers.

The model can also depend on the availability of resources in communities. In a city without a good bus system, a family might not be able to reach a tertiary care provider, while a primary care provider may be nearby. In addition, a care management strategy for a cystic fibrosis program might look different than the care management strategy for children with spina

bifida, who may have many more providers and more opportunities for surgical intervention.

As demonstrated by previous presentations at the workshop, many opportunities exist to disseminate and replicate excellent programs, Houtrow concluded. But success requires communication and coordination as well as dissemination.

INSURANCE COVERAGE FOR CHILDREN WITH COMPLEX MEDICAL NEEDS

A prominent topic that arose in the discussion session involved reimbursement for children with complex medical conditions. As Edward Schor of the Lucile Packard Foundation for Children’s Health pointed out, the health care reimbursement system is designed for acute care, but disabilities and complex needs are chronic issues and out of sync with reimbursement. Also, good measures of individual or family functioning do not exist, even though such measures could help make the case to payers to cover a service on cost-effectiveness grounds. Similarly, McCabe noted that some patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder have insurance policies that consider it an educational problem and will not cover it.

On this topic, Houtrow lamented the dichotomization between physical health or medicine and behavioral health, which is also embedded in payment structures and policies. “Although we would like to consider the whole child, we’re often facing barriers related to whether there’s a carve-out where those services can be provided, or the stigma associated” with a condition, she said. This contributes to fragmented care that is not coordinated or organized in a way that is easy to access and to use.

Also, different families need different things at different times. As such, people from outside a health care system might be leading the team serving a child’s and family’s needs, such as someone from a foster care agency. “When you play on a team, you aren’t always holding the ball, but you need to be always ready to take it, and you need to know how to help the other people drive the ball forward,” Houtrow said. Everyone has various sets of skills and strengths that children will need at different times and different places.

Ongoing changes in the health care system, such as the move to measure quality and the move away from fee-for-service care, have associated risks for children with disabilities. But there are also opportunities to learn from these different models as reform continues, Houtrow added. Today, health care providers have to maintain large volumes of patients to survive financially, which makes it difficult to serve children with complex needs. That points to the need for continuous insurance that protects families from unmet needs and does not cost too much. “We have a lot to think about—

not only payment reform for the physician, but structural reform for how we make sure that coverage is delivered,” Houtrow said.

Schor also pointed out that getting a team to be physically located together is complex, especially when teams need to form and re-form for children and families with different needs. As Houtrow said, people need to understand their roles and skill sets. “It often comes down to face-to-face communication so that people know what they’re expected to do, what their shared responsibility is, and how they are achieving shared goals. . . . It’s very tough, and the way we do it clinically is face-to-face every week,” she said.