1

Introduction

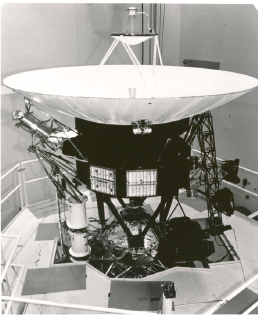

At this moment, Voyager 1 and 2 are traveling away from the Sun, probing the outer edges of our solar system and analyzing the interaction of the solar wind and the interstellar medium nearly four decades after launch. The two Voyager spacecraft have contributed to our understanding of the giant planets of our solar system as well as the limits of the Sun’s influence, but it is easy to forget that both Voyagers ended their primary mission phases soon after their encounters with Saturn, which for Voyager 2 occurred in summer 1981. More than 30 additional years of scientific discovery by the Voyagers have resulted from repeated extensions of the mission (Figure 1.1).

The Voyagers are not alone in functioning long after their planned prime mission. Many NASA science spacecraft—including but not limited to the Chandra X-Ray Observatory and the Kepler telescope; the Opportunity rover, the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, and Cassini; the Aura, Aqua, and Terra Earth sciences spacecraft; the ACE and Wind spacecraft in interplanetary space between Sun and Earth, the THEMIS magnetospheric orbiter, and the SOHO and STEREO solar observatories—have provided incredible scientific value long after their primary missions.

These lengthy missions and their incredible scientific productivity are not simply due to happenstance or the unexpected longevity of some spacecraft: Extended missions are a mainstay of NASA’s scientific endeavor, a major part of the agency’s science portfolio, and the result not only of impressive engineering but also of careful management and effective planning.

NASA’s Science Mission Directorate (SMD) operates several dozen spacecraft in Earth orbit and beyond. When these spacecraft were first launched, they entered what is known as the prime phase of their mission. During the prime phase, the spacecraft measurements are focused on achieving a specific set of mission objectives aimed at answering high-priority science questions. The objectives usually require measurements over one to several years and may be tied to the characteristics of the science target. For instance, 1 year at Mars lasts approximately 2 Earth years, so many Mars missions have prime phases lasting 2 Earth years. Spacecraft are designed to last through the proposed prime mission with a high level of certainty. They are tested to prescribed limits and include margins that ensure that a spacecraft has a high probability of achieving its design lifetime. These margins allow—but do not guarantee—the ability to use the spacecraft for well beyond the design lifetime.

After a mission has completed its prime phase, it can be considered for an extension, provided it is still operational and can make important scientific contributions. The decision to extend a mission is made via a deliberative process within SMD. Mission teams prepare a scientific and technical proposal that also contains relevant budgetary information. The proposals are reviewed by a peer advisory panel selected by the director (or their designee) of

SMD’s division for Astrophysics, Heliophysics, Earth Science, or Planetary Science (depending on which division supports the mission). A subsequent review by the division director takes into account various administrative considerations. A statute requires that such reviews (called Senior Reviews) take place every 2 years; however, there is no statutory definition of how such reviews must be conducted. Therefore, responsibility for defining and conducting each division’s Senior Review resides with the division of SMD in which it is held.

THE SCIENCE MISSION DIRECTORATE

SMD is tasked with helping to fulfill the goals of the national science agenda, as directed by the executive branch and Congress and advised by the nation’s scientific community. In doing so, SMD conducts scientific exploration missions that use spacecraft instruments to provide observations of Earth and other celestial bodies and phenomena.

SMD is allocated slightly less than one-third of NASA’s overall budget. In recent years SMD’s budget has been as follows:

- 2015 actual: $5.2 billion out of $18.0 billion total;

- 2016 enacted: $5.6 billion out of $19.3 billion total.

NASA currently has approximately 60 active space science missions with more than 20 additional missions currently under development—and missions can consist of multiple spacecraft. These spacecraft are sponsored by the Astrophysics, Heliophysics, Earth Science, and Planetary Science Divisions. Table 1.1 provides budget details for each of the four SMD divisions, along with data for the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), which is separated from the Astrophysics Division for budgetary, management, and development purposes. Nonetheless, the science of JWST is largely astrophysical in nature, and it is treated as an Astrophysics Division mission in the remainder of this report. Table 1.2 shows the currently active extended missions in each division.

TABLE 1.1 NASA Science Mission Directorate (SMD) Division Budgets (in $ million)

| 2015 Actual | 2016 Enacted | |

|---|---|---|

| NASA Total | 18,010.2 | 19,285.0 |

| SMD | 5,243.0 | 5,589.4 |

| Earth Science | 1,784.1 | 1,921.0 |

| Planetary Science | 1,446.7 | 1,631.0 |

| Astrophysics | 730.7 | 730.6 |

| James Webb Space Telescope | 645.4 | 620.0 |

| Heliophysics | 636.1 | 649.8 |

TABLE 1.2 The 45 NASA Missions in Extended Phase as of February 2016

| Heliophysics | Earth Science | Planetary Science | Astrophysics |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACE | Aqua | Cassini | Chandra |

| AIM | Aura | LRO | Fermi |

| Geotaila | CALIPSO | Mars Expressa | Hubble |

| Hinodea | CloudSat | Mars Odyssey | Kepler |

| IBEX | EO-1 | MAVEN | NuSTAR |

| IRIS | GRACE (1/2) | MER Opportunity | Spitzer |

| RHESSI | LAGEOS (1/2) | MRO | Swift |

| SDO | Landsat 7 | MSL Curiosity | XMM-Newtona |

| SOHOa | OSTM/Jason-2 | NEOWISE | |

| STEREO (1/2) | QuikSCAT | ||

| THEMIS | SORCE | ||

| TIMED | Suomi NPP | ||

| TWINS (A&B; 1/2) | Terra | ||

| Voyager | Van Allen Probes | ||

| Wind |

a These missions are primarily foreign-led with some NASA participation.

NOTE: Numbers in parentheses indicate remaining spacecraft operating, compared to the original number. Acronyms are defined in Appendix F.

The Astrophysics Division focuses on understanding the universe beyond the solar system, seeking to catalog and understand astronomical phenomena such as black holes and exoplanets. Some missions are designed to observe the effects of dark matter, others to probe dark energy and to explore the origins of the cosmos. During 2016, there were approximately 10 active missions in the Astrophysics Division.

Heliophysics is the study of the Sun, the solar wind, and the physical domain dominated by solar activity, the heliosphere. The goals of the Heliophysics Division range from understanding the active processes within the interior of the Sun that drive the system, to measuring the space environments of Earth and other bodies within the solar system, stretching out to interstellar space. The Heliophysics Division during 2016 was responsible for approximately 16 active missions.

Earth science comprises the study of the diverse components that make up Earth as a planetary system, including the oceans, atmosphere, continents, ice sheets, and biosphere. Using observations on a global scale, the Earth Science Division (ESD) seeks to improve national capabilities to understand and predict climate, weather, and

natural hazards; manage natural resources; and collect the knowledge needed to develop environmental policy. During 2016, there were approximately 20 active missions in this division.

The Planetary Science Division is responsible for sending robotic spacecraft and landers to Earth’s Moon, to the other planets and their moons, and to smaller celestial bodies, including asteroids and comets. These exploration activities are undertaken in order to better understand the origin and nature of the solar system and to provide a path forward for future human exploration. During 2016, there were approximately 14 active Planetary Science Division missions.

WHAT IS AN EXTENDED MISSION?

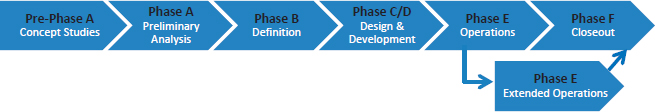

NASA missions progress through multiple phases (A-F), from early concept studies to end of life (Figure 1.2). Phase E is the operational phase of a mission. This can include transit to the science-gathering location (such as a Lagrange point for an astrophysical observatory, or a planet) and the science-gathering phase.

All missions have a prime phase during which they collect data and answer their top-level science questions. Spacecraft are designed and tested to specified lifetimes. Nevertheless, just as home appliances like dishwashers rarely stop working the day after the warranty expires, NASA spacecraft typically continue working after completing their prime phase. (This issue is further described in Chapter 4.) As a mission nears the end of its prime phase, the project team can request a mission extension through the relevant division’s Senior Review process. Extended operation may be approved if a mission can collect data that will help to answer new science questions that were not anticipated when the mission was first formulated, or extend the existing data sets and improve understanding of the subjects being investigated. Table 1.2 lists SMD’s current missions in extended operations.

The Senior Review process begins when SMD division issues a call for proposals, including guidelines for proposal content, several months before the desired due date. Proposing teams respond with written proposals that explain the accomplishments of the mission to date, the proposed observations that would be conducted during the mission extension and their scientific value, and the cost to support the observations for the period of time under consideration (typically the 2-year period until the next Senior Review). After submission and initial review of the written proposals, the Senior Review panel invites the proposal teams to give an oral presentation to the panel and answer questions about the proposed extended-mission activities. After a period that is usually on the order of a few weeks, the panel delivers to the relevant SMD division director a written report that contains the panel’s assessment of the merit of each mission proposal under consideration in that division that year. Taking into consideration the panel’s recommendation, as well as any programmatic or other factors, the director then decides which missions to continue, end, or reduce in scope. Additional details describing how the Senior Reviews vary between divisions are described in Chapter 3.

Most missions entered their extended mission phase after being recommended to do so by a Senior Review panel conducted within their division. There have been some exceptions. For instance, the NEOWISE mission, which is currently conducting a survey for near-Earth objects that could potentially impact Earth, was strategically directed to continue operations to satisfy agency requirements. It is not subject to the Senior Review process.

NASA’s Associate Administrator for Space Science John Grunsfeld1 regularly encountered what he referred to as “urban myths of extended missions.” These include the following: SMD spends most of its budget on extended missions for limited science return; NASA cannot build new missions because of the cost of extended missions; and NASA never terminates any missions. Dr. Grunsfeld stated that all of these claims are inaccurate and provided the committee with data that refuted them.

The first urban myth relates to the scientific productivity of extended missions. Dr. Grunsfeld explained to the committee that, despite spending only a modest percentage of the SMD budget on missions in extended phase, the scientific return from those missions has been substantial. Chapter 2 of this report is devoted to identifying a number of major scientific discoveries made by missions in their extended phase, indicating that extended phase missions make major scientific contributions.

WHAT DO NASA’S EXTENDED MISSIONS COST?

In addition to Dr. Grunsfeld’s presentation, the committee heard from the four science division directors who presented further budget information about their directorates. They indicated that the amounts they spend on mission extensions vary. For example, in 2015 Earth Science Division (ESD) spent approximately 7 percent of its budget on extended missions and approximately 9 percent for 2016. The Astrophysics Division (ASD) spent approximately 17 percent of its budget in 2015 on extended missions, and 15.4 percent in 2016. In the Heliophysics Division (HD), 13 percent of the 2015 budget went to extended missions, and 12 percent in 2016. The Planetary Science division (PSD) spent 15 percent of its budget on extended missions in 2015, and 13 percent in 2016. Budget charts for fiscal year (FY) 2016 for all four NASA divisions are included in Appendix C.

NASA provided rather detailed information, year-by-year for FY2011-FY2015, showing the budget for each extended mission, the total for extended missions, and the total for all of SMD. Over the 5-year period, the total budget for extended missions ranged from $544 million to $591 million with the average over the 5 years at $567 million. The average budget for SMD over the same 5-year period was $5.03 billion. Thus, the extended missions accounted for 11.3 percent of the SMD funding from 2011 to 2015.

These numbers are the total listed under extended missions. However, there are additional funds expended on science from extended missions. In some cases, scientific research is supported through the mission line, but additional research may be supported under various research and analysis (R&A) or similar accounts in the four SMD divisions.

The split of research supported by mission lines and by R&A accounts varies from division to division and from year to year. Moreover, accounting is complicated by the fact that research may use data from the prime mission phase, from the extended phase, or from a mix of the two. Some of this research would be supported under R&A even if the relevant extended mission were to end, whereas some of it is tied to new observations acquired as an extended mission continues.

The committee heard that extended science mission budgets have fluctuated over time and will continue to do so based on many factors, including spacecraft health, the results of the Senior Reviews undertaken by the divisions, and other agency considerations. However, as discussed above, the overall SMD expenditure on extended science missions has averaged around 12 percent, which is significantly less than what is spent on missions in development, typically on the order of 50 percent (as calculated by combining the overall SMD development budget numbers for FY2016, which are shown graphically by division in Appendix C). The relatively small fraction spent on extended-phase missions compared to missions under development indicates that even if NASA were to end all extended missions in a division, the amount of funding this would free up for new missions would be of modest impact. The committee further addresses this issue in Chapter 4.

Another of the urban myths relates to the perception that SMD does not terminate missions that have outlived their utility. Then-Associate Administrator Grunsfeld explained to the committee that SMD has ended numerous space missions over the past two decades (see Table 1.3). In some cases, missions were terminated when the spacecraft could no longer be operated (e.g., the Spirit rover and the GRAIL lunar spacecraft), but the agency has also ended its support for some missions after finding that their science productivity no longer warranted support.

___________________

1 Dr. John Grunsfeld was NASA’s Associate Administrator for Space Science through April 2016.

TABLE 1.3 Examples of Science Missions Ended During Previous Two Decades

| Mission | |

|---|---|

| IUE | Terminated 1996 |

| ISEE-3/ICE | Ended 1997; recently rebooted by non-NASA group |

| Compton Gamma Ray Observatory | De-orbited June 2000, to avoid potential uncontrolled re-entry |

| EUVE | Decommissioned January 2001 |

| SAMPEX | NASA funding ended June 2004, operated by Bowie State University thereafter until 2012 at no cost to NASA |

| CHIPS | NASA funding ended 2005; UCB operated until 2008 |

| FAST | NASA funding ended 2005 |

| ERBS | Terminated October 2005 |

| Polar | Ended in 2007 |

| Gravity Probe B | Funding ended 2008 |

| TRACE | Terminated June 2010 after success of SDO |

| WMAP | Ended October 2010 after four extensions |

| GALEX | Terminated February 2011 |

| WISE | Terminated in Astrophysics February 2011, restarted in Planetary Science in August 2013 for near-Earth object searching |

| RXTE | Terminated January 2012 |

| QuikSCAT | Planned to be decommissioning in 2015, but continued following RapidScat issues |

NOTE: Acronyms defined in Appendix F.

HOW DOES NASA DECIDE WHAT MISSIONS TO EXTEND?

A key aspect of the process for extending NASA science missions is the Senior Review. The requirement for this review is established in legislation as follows:

The Administrator shall carry out biennial reviews within each of the science divisions to assess the cost and benefits of extending the date of the termination of data collection for those missions that have exceeded their planned mission lifetime.2

The requirement was initially established in the 2005 NASA Authorization Act and repeated in the 2010 NASA Authorization Act. NASA ASD began conducting Senior Reviews of its missions in the early 1990s and established a 2-year cadence for such reviews. According to former congressional staffers who spoke to the committee, the Authorization Act language calling for biennial reviews was based in part on this previously established cadence and was in part somewhat of a guess, with one former staffer suggesting that, in Washington, D.C., “two is the average between one and infinity.”

NASA’s overall policies for extending science missions are outlined in the agency’s management plan. The 2013 Science Mission Directorate Management Handbook states that after a mission’s prime phase, entry into an extended phase “is possible if part of a compelling investigation that contributes to NASA’s goals” (NASA, 2013). This document also defines SMD’s implementation for the Senior Review process, which is codified, yet flexible for the needs of each division, and involves an evaluation of the productivity of the proposed extended mission by members of the scientific community.

NASA conducts Senior Reviews for astrophysics and planetary science missions in even-numbered years and

___________________

2 National Aeronautics and Space Administration Authorization Act of 2005, P.L. 109-155, Section 304, “Assessment of Science Mission Extensions,” December 30, 2005.

for Earth science and heliophysics missions in odd-numbered years. The Senior Review processes for the four divisions are discussed in detail in Chapter 3.

The following chapters in this report review in greater detail the scientific return secured from extended missions, the process that is in place to ensure that extended missions are productive contributors to NASA’s science goals, how the relatively modest costs associated with supporting extended missions compares to the support required for new mission development and the potential for science lost if extended missions are not supported, and the potential ways in which extended missions may realize cost savings relative to their prime phase.

REFERENCE

NASA. 2013. Science Mission Directorate (SMD) Management Handbook. Washington, D.C., October.