3

Recommendations and Barriers to Implementation

It is beneficial to address the barriers the Air Force faces in owning the technical baseline of its acquisition programs in the context of the key topics outlined in the report of the workshop on ownership of the technical baseline (OTB) (leadership and culture, workforce management, contracting support, and funding). Throughout the following sections, the committee will highlight the key barriers to the Air Force owning the technical baseline of its acquisition programs and will offer recommendations for eliminating them.

LEADERSHIP AND CULTURE

It is clear that a strong sense of shared mission ownership, declared and upheld by senior leadership and shared down the chain of command, is critical to fostering quality program management and successful program outcomes. This section discusses leadership and cultural barriers to owning the technical baseline in Air Force acquisition programs. This discussion highlights the importance of consistent tenancy in the Air Force’s acquisition leadership positions and the need for changes in the Air Force’s risk-averse culture.

The Air Force has ceded ownership of the technical baseline in many acquisition programs. The process began with decisions made and executed by the Department of Defense (DoD) and Air Force leadership in the mid-1990s and evolved over time. The ongoing tension between funding for operational priorities and support for acquisition personnel; indiscriminant application of the total systems performance responsibility (TSPR) approach; ethics violations involving Air Force

senior acquisition personnel in the acquisition community; and an erosion of the organic technical workforce in response to budget reductions have engendered a series of actions and reactions that have negatively impacted the Air Force’s organizational culture. This culture—defined as a system of shared assumptions, values, and beliefs that governs and influences how people act, interact, and perform their jobs—is instrumental in the Air Force’s ability to own the technical baselines of its current and future programs. In addition, there has been a clear shift in recent years toward a risk-averse culture within the Air Force acquisition community. Over the past two decades the Air Force has adopted a culture of “just saying no,” replacing the team-oriented culture of “here is a way to achieve the technical mission and objectives within our legal and ethical bounds.”1

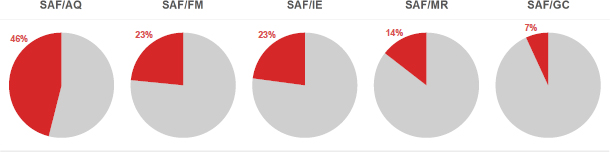

A key issue in the Air Force acquisition community is a persistent lack of continuity in the position of Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Acquisition (SAF/AQ), especially in relation to the continuity seen in other senior Air Force positions. Figure 3.1, compares the amount of time several president-appointed, Senate-confirmed USAF positions were designated as “acting” or “vacant” since January 2000.2 The figure clearly shows the disparity between the SAF/AQ position and the other Senate-confirmed positions in the Air Force. It is unclear why this disparity exists. While the Air Force does not control all aspects of the nomination and confirmation processes, it can still advocate that the SAF/AQ position be filled as quickly as possible within the constraints and timelines of the process. Prolonged vacancies of the SAF/AQ position have, over time, eroded the necessary senior leadership and hierarchical support for program executive officers (PEOs) and program managers (PMs), particularly when making potentially controversial decisions about mission-critical defense programs.

CONCLUSION 1: Consistent tenancy in the position of Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Acquisition will help to revitalize, focus, and provide visible support for the acquisition community’s critical role in program development and execution.

RECOMMENDATION 1: The Secretary of the Air Force should investigate why the position of Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Acquisition is in an acting or vacant status more frequently than other Air Force Assistant Secretary positions. This investigation should consider how the Air Force, along with other Services and government agencies, fills similar critical positions and

___________________

1 Vice Admiral David A. Dunaway (USN, retired), former commander of Naval Air Systems Command, interview with the committee on February 8, 2016.

2 U.S. Air Force, Key Personnel, Headquarters United States Air Force, Air Force Historical Studies Office, January 2013, http://www.afhso.af.mil/shared/media/document/AFD-130410-035.pdf.

should focus on identifying best practices for implementation. The Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Acquisition position should not be vacant for any extended period of time, and the use of an acting individual should be minimized. Furthermore, in order to attract competitive talent, the Air Force should ensure that it does not impose any additional restrictions beyond those required by law, especially relative to the post-employment period, for the position of Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Acquisition.

The Air Force acquisition culture emphasizes process and the pursuit of perceived cost reductions. The risk-averse culture of Air Force acquisition is governed primarily by process compliance, the cost of which is estimated to account for nearly 25 percent of every dollar spent.3 The high level of oversight4 in place

___________________

3 The Honorable Stan Soloway, President and CEO, Professional Services Council, interview with the committee on January 14, 2016.

4 The Under Secretary of Defense, the Honorable Frank Kendall said in his memorandum “Implementation Directive for Better Buying Power 3.0—Achieving Dominant Capabilities through Technical Excellence and Innovation,” section “Streamline documentation and staff review” the following: “In [Better Buying Power] BBP 2.0, we tracked how much time is logged to prepare for staffed document reviews and decision review briefings. The Government Accountability Office has also recently released a study on document lead times and value. Our data indicates that excessive program management time is spent supporting staff reviews and preparing documents primarily for review, instead of focusing on program execution. The Department will continue and increase the effort to reduce documentation and reviews. Program managers are expected to suggest tailoring throughout the program lifecycle” (April 9, 2015, p. 20, http://www.acq.osd.mil/fo/docs/betterBuyingPower3.0(9Apr15).pdf).

for military programs, and the weight of meeting the oversight requirements, constrain and hinder programs and program staff.5 A symptom of a risk-averse culture is that personnel often use the most restrictive interpretation of a policy, and even though processes allow for the elevation of issues, it is rarely done. This risk-averse posture can hinder the innovative problem-solving mindset of even the most seasoned acquisition executive.6 There is a perceived culture of acceptance in some Air Force acquisition programs that fosters the development of program managers who only verify the existence of results from the contractor and perform minor, if any, independent technical verification and validation. These program managers, along with their acquisition teams, were forced to abandon their role of organic engineering analysis by policy constraints and funding reductions. However, such organic engineering analysis is often necessary to assure that program and technical decisions best meet mission requirements. This new paradigm threatens the ability of the Air Force acquisition enterprise to deliver “war-winning” capabilities within cost and on schedule. Oversight is replacing program risk management and is actually creating more program risk by reducing verification and validation.

In an Air Force culture that has devalued the role of acquisition management and personnel, program management positions have often come to be regarded as career path stepping-stones rather than as coveted and important leadership positions. Program managers and engineers—those who have the most knowledge of program risk—have a seat at the table but often do not have respected input when making decisions related to program risk and are largely unappreciated in terms of both numbers and authority for technical and program management. Engineers in the Air Force have a voice, but they often do not have a vote.7 These practices are in contrast to the acquisition era prior to TSPR, when engineers not only had a voice and a vote but often were the prime assessors of program technical risk and the associated cost, schedule, and performance risk.

CONCLUSION 2: The current risk-averse culture, along with the gap in technical engineering expertise within Air Force acquisition programs, hinders program managers from making informed, timely, and independent decisions. This culture is negatively impacting programs and is a driver of rising costs and protracted schedules.

___________________

5 Blaise Durante, Director, Blaise J. Durante & Associates, Inc., interview with the committee on February 9, 2016.

6 The Honorable Jack Gansler, professor emeritus, University of Maryland School of Public Policy, and Former Undersecretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics, interview with the committee, February 8, 2016.

7 Jorge Gonzalez, Director of Engineering and Technical Management/Services Directorate, Air Force Life Cycle Management Command (AFLCMC), interview with the committee, March 30, 2016.

RECOMMENDATION 2: Air Force senior leaders should define, develop, and execute a strategy that balances risk and reward from a program implementation viewpoint, fosters a learning environment characterized by healthy tension and debate, and actively rewards acquisition personnel that regularly find a “pathway to yes.” A risk-tolerant8 acquisition culture, in concert with a sense of urgency, is critical to agile and timely acquisition for the Air Force to maintain its advantage against rapidly evolving threats. Significant attention should be given to the proliferation and acceptance of this crucial change. The strategy should include the following at a minimum:

- Establishing an education and training program to promote and develop a risk-tolerant culture that includes the use of current and former experienced acquisition professionals to provide guidance and mentorship.9

- Encouraging the pursuit of more reasonable interpretations of policy and process flexibility to more efficiently accomplish program goals while maintaining compliance.

- Assuring that logical and reasonable deviations from policy or requirements can be expeditiously pursued by empowered acquisition personnel.

WORKFORCE MANAGEMENT

The following discussion of workforce management addresses the need to adequately staff technical positions within the Air Force, as well as the need for consistent and continuous management in key programmatic roles, sound career management practices to retain engineering and acquisition talent, and the use of appropriate contracting vehicles to support the technical workforce where necessary. In addition, widely recognized best practices in both the federal agencies and industry are available for the Air Force to consider and employ.

The Air Force has gradually reduced its organic technical workforce10 through a combination of service downsizing, devaluing technically trained personnel, cost--

___________________

8 Paraphrasing from David Hillson’s book Effective Opportunity Management for Projects, Exploiting Positive Risk (Marcel Dekker, New York, 2004), the term “risk tolerant” is viewed as “being reasonably comfortable with most uncertainty and accepting it exists as a feature of life or business.”“Risk averse,” on the other hand, is viewed as “being uncomfortable with uncertainty, having a low tolerance for ambiguity, and seeking security and resolution in life and business.”

9 This recommendation aligns with points outlined in the 2013 memorandum of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics on key leadership positions and qualification criteria (November 8, available at https://acc.dau.mil/adl/en-US/684463/file/75211/USA001464-13%20USD(AT_L)%20Key%20Leadership%20Positions%20and%20Qualification%20Criteria%20Memo%20(8%20Nov%2013).pdf).

10 Organic technical workforce includes both military and government civilians.

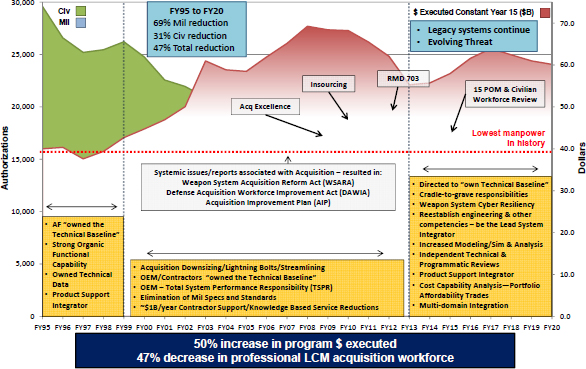

cutting measures, and attrition. Additionally, program growth has occurred simultaneously with this loss of workforce. This gradual loss, as evident in Figure 3.2, in some cases led the Air Force to assign personnel who lack the necessary technical education or expertise to the role of PEO or PM, handing over control of the technical baseline to prime defense contractors.11 Accordingly, the duties of technically trained Air Force personnel have evolved—once directly engaged in technical work, they now primarily monitor contractors doing that work.

The Under Secretary of Defense’s April 2015 memorandum to the Services on “Implementation Directive for Better Buying Power 3.0—Achieving Dominant Capabilities through Technical Excellence and Innovation,” provides guidance to strengthen organic engineering capabilities. The memorandum specifically states that12

DoD cannot effectively support the Warfighter nor retain its technological superiority without a competent and innovative organic engineering workforce, both military and civilian. The goal of this initiative is to strengthen our organic engineering capabilities by equipping our technical workforce with essential education, training, and job experiences, along with the right physics-based tools, models, data and engineering facilities to efficiently and effectively manage the technical content of our complex products throughout their lifecycle. The Department also needs to take active steps to strengthen organic engineering capabilities to better understand the technical risks associated with program execution for its development programs, and this requires a strong engineering workforce.

It is clear that, at present, the Air Force cannot own the technical baseline in all appropriate programs. The ability to own or regain ownership of the technical baseline in the Air Force is complicated by a lack of capacity to meet current and emerging engineering and technical demands. This is driven in part by the lack of a clear and valued career path for uniformed engineers in the Air Force, which hinders development of adequately qualified acquisition personnel.13 Careful analysis will be needed for the Air Force to determine how it can create career paths for uniformed engineers so there will be enough senior, technically competent, and programmatically experienced acquisition professionals to manage major acquisition programs. An effective analysis will specifically look at the way the Navy and other services and agencies manage their technical resources. The Air Force’s situ-

___________________

11 Douglas L. Loverro, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Space Policy, Department of Defense, interview with the committee on March 30, 2016.

12 Under Secretary of Defense, “Implementation Directive for Better Buying Power 3.0, Achieving Dominant Capabilities through Technical Excellence and Innovation,” April 9, 2015, p. 23, http://www.acq.osd.mil/fo/docs/betterBuyingPower3.0(9Apr15).pdf.

13 Jorge Gonzalez, Director of Engineering and Technical Management/Services Directorate, AFLCMC, interview with the committee on March 30, 2016.

ation is further complicated by the fact that there are simply not enough engineers within the Air Force Life Cycle Management Center (AFLCMC) to meet current demands14 for technical work, let alone to take on additional programs.15

The authorizations in fiscal year (FY) 2020 for the acquisition workforce in the AFLCMC are projected to result in an overall reduction of 47 percent below FY1995 levels.16 Additionally, the ratio of program engineers to program managers has dropped to 4:1, as contrasted to the previously robust high of 10:1.17 It is difficult to qualitatively assess what effect such a reduction in engineering support

___________________

14Appendix D consists of a memorandum on owning the technical baseline by Lt. Gen. John F. Thompson, the Commander of the AFLCMC, dated June 20, 2016.

15 Ibid.

16 See Figure 3.2.

17 Jorge Gonzalez, Director of Engineering and Technical Management/Services Directorate, AFLCMC, interview with the committee on March 30, 2016.

has had, but it is notable. Experience shows that the responsiveness and timeliness of the engineering staff to technical matters is related to the depth of experience and the number of qualified engineers available.

The USAF has found itself in an acquisition crisis. Whenever it needs to make informed, timely, and independent decisions related to the technical baseline it needs to own that baseline. Owing to the resource constraints and the fact that acquisition programs in the Air Force are in different stages of their development; have varying contract mechanisms and end products; and have various ranges of technical complexity, there is no “silver bullet” for fixing the issue of owning the technical baseline.

CONCLUSION 3: The USAF is “over-programmed,” and its organic technical workforce is critically understaffed. This combination is highly detrimental both to the sustainability of current weapon system programs and to the health and success of future programs. The reduction in the organic workforce, coupled with a loss of technical education and experience, has subsequently hampered the Air Force’s ability to attain or regain control of the technical baseline when it is most needed.

RECOMMENDATION 3: The Air Force should continue and complete its efforts to determine which current programs should own the technical baseline and develop staffing standards to determine the proper mix and number of military and civilian engineers required to own the technical baseline for those programs.18 Criteria should be established for when the Air Force should own the technical baseline19 as opposed to having knowledge of the baseline as technical integrator or interface systems reviewer. The decision to own the technical baseline for future programs should be included in the acquisition milestone protocol as gated decision points. Additionally, the Air Force should develop methods to measure whether or not selected programs have successfully achieved, and are maintaining, ownership of the technical baseline. Cost overruns, schedule delays, and unidentified, or incorrectly identified, key performance parameters (KPPs) are potential measurement points.

___________________

18 This recommendation is in line with Recommendation 2-2 from the National Research Council report Examination of the U.S. Air Force’s Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) Workforce Needs in the Future and Its Strategy to Meet Those Needs. That report says “the Air Force should review and revise as appropriate its current requirements and preferences for personnel with STEM capabilities in every career field and occupational series” (The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C., 2010, p. 32).

19 Examples of programs for which the Air Force could apply and test the developed criteria would be, but are not limited to, B-21, GPS OCX, Joint Stars Recapitalization, DCGS, GPS III.

In the acquisition community, the personnel rules and regulations that govern the assignment type, variety, and tour length necessary for promotions in rank and career advancement have had a negative impact on program management. Civilian and military personnel typically rotate out of programs too rapidly to acquire the experience, insight, competence, and confidence necessary for managing large, complex, and indispensable defense programs.

These short tours hinder or are detrimental to the management of the technical workforce, which in turn prevents effective ownership of the technical baseline and can negatively impact cost and schedule. Even the most capable leaders grapple with a demanding learning curve when they first enter a new position, while the workforce simultaneously adjusts to the new leadership’s priorities, needs, and intents. This further hinders the program’s progress, effective decision making, and success within a timeline that does not compensate for personnel turnover and often does not account for a transition period from one program manager to the next. Major programs demand continuous attention to oversight, as well as attention to emergent technical, business, and funding issues in order to be effective and successful.

Historically, the USAF valued the military members of the engineering workforce and provided retention bonuses to them for up to 10 years so the USAF could retain them for an entire 20-year period.20 The funding for these types of incentives appears to have been realigned to “higher priority” areas of the Air Force or totally zeroed out. However, the first overrun on a major defense acquisition program (MDAP) would more than pay for engineering bonuses21 and the lost incentives that were so crucial to delivering successful programs in the past. A small portion of the approximate $14 billion cost overrun of the Air Force’s space-based infrared system (SBIRS) could easily fund the essential growth in numbers and retention of engineers and technical personnel necessary to regaining technical capabilities in the USAF workforce.22

CONCLUSION 4: The Air Force currently lacks personnel stability, driven by personnel rotation and lengths of assignments, in its program offices, thus impacting program knowledge management within the program office.

RECOMMENDATION 4: The Air Force should review, and make appropriate changes to, current assignment policies and practices for the acquisition workforce to reduce turnover and attrition and increase succession and transi-

___________________

20 Douglas L. Loverro, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Space Policy, interview with the committee on March 30, 2016.

21 Ibid.

22 M. Gruss, Unlocking the SBIRS Data Revolution, Space News Magazine, April 25, 2016, pp. 11-13 and 25, http://www.spacenewsmag.com/feature/unlocking-the-sbirs-data-revolution/.

tion planning; should invest in a more structured mentoring program across the acquisition workforce to increase the sharing of best practices; and should ensure that the career management system for the acquisition workforce be charged with providing appropriate educational opportunities, training, and industrial experiences to acquisition personnel. The intent of the review should be to create strong career paths for acquisition personnel, reflecting the critical value of acquisition to future Air Force operations.

Owning the technical baseline is both critical to, and relies on, effective program management with technically competent individuals who can make informed and timely decisions that are critical to mission success. Better Buying Power 3.0, Interim Release noted as follows:

We would not expect to see a non-lawyer supervising a group of trial lawyers litigating cases, and we would not expect to see a non-surgeon supervising a group of doctors performing surgery. We should also not expect a Program Manager with no technical education or experience in engineering to supervise a development program.23

The Air Force Officer Classification Directory24 (AFOCD) describes the Air Force’s Acquisition Utilization Field25 as encompassing “staff and management functions peculiar to the Air Force acquisition life cycle.” The directory continues as follows:

It is desirable that entry into the career field be preceded by assignment in another utilization field whenever possible. Officers who enter the career field on their initial tour should seek a subsequent assignment in another utilization field followed by a return to the acquisition program management career field. This desired career broadening is to provide a better perspective and understanding of the interfaces between functions of acquisition management and related functions in the developing, operating, training, and support commands. Lateral inputs will include only those officers who have clearly demonstrated a potential for effective administration and program management beyond their basic specialty.

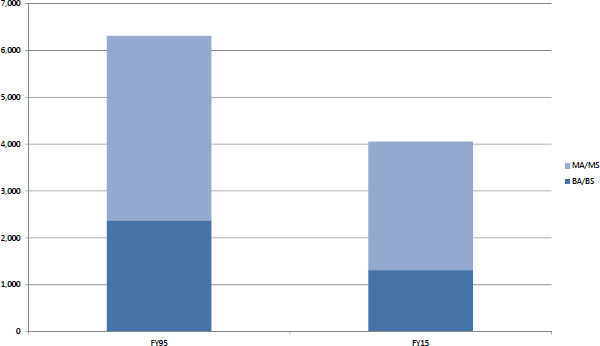

In FY1995,26 there were more than 6,500 Air Force officers in the Developmental Engineering Utilization Field (62XX) and the Acquisition Utilization Field (63XX). Of those officers, 36 percent possessed a bachelor’s degree and 60 percent

___________________

23 F. Kendall, Better Buying Power 3.0, Interim Release, September 19, 2014, p. 10, http://www.acq.osd.mil/dpap/sa/Policies/docs/BBP_3_0_InterimReleaseMaterials.pdf.

24 U.S. Air Force, Air Force Officer Classification Directory (AFOCD), The Official Guide to the Air Force Officer Classification Codes, 2013, p. 216, http://www.uc.edu/content/dam/uc/afrotc/docs/UpdatedDocs2013/AFOCD_30Apr13.pdf.

25 USAF Specialty Code 63XX.

26 Data were filtered by FY1995 and FY2015, active duty Air Force officers only, Air Force Specialty Codes 62XX and 63XX only, and education level (highest).

possessed a master’s degree as their highest education level. In FY2015, the total number of officers in the 62XX and 63XX fields had dropped to just over 4,300. Of those officers in FY2015, 30 percent possessed a bachelor’s degree and 64 percent possessed a master’s degree as their highest education level.27Figure 3.3 highlights the sharp decline in the total number of officers in the 62XX and 63XX between FY1995 and FY2015.

While the data presented above confirm the previously discussed decline in the number of Air Force 62XX and 63XX officers, they pertain only to the education levels of those officers and do not account for past technical experience. The committee heard anecdotal evidence that, until the 1980s, the desire for assignments in other utilization career fields prior to entry into the Acquisition Utilization Field (63XX) was regularly adhered to. Today’s Air Force acquisition leaders and personnel system appear to often allow a new entrant to become a 63XX without adhering to the prerequisite of technical experience.28 Over the same time span, other

___________________

27 Data extracted from Air Force Personnel Center, “Report Builder Step 1 of 3,” accessed August 17, 2016, http://access.afpc.af.mil/vbinDMZ/broker.exe?_program=ideaspub.IDEAS_Step1.sas&_service=pZ1pub1&_debug=0.

28 Douglas L. Loverro, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Space Policy, interview with the committee on March 30, 2016.

organizations, such as the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), have required program managers to demonstrate technical know-how and experience. Additionally, the USAF used to fund Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) engineering scholarships and would assign as many as 70 USAF engineers to ROTC as trainers and mentors to groom future engineers.29 These ROTC trainers received bonuses to take on this valued and critical assignment.

Academic education levels and experience in other assignments prior to entering acquisition career fields fail to account for experience outside of the Air Force. The Education with Industry (EWI) program dates back to the birth of the Air Force in 1947.30 The program is, as per the program handbook, “a highly selective, competitive non-degree educational assignment within an industry related to the student’s career field.” The EWI program was originally developed because Air Force leadership “determined that it needed a corps of talented officers who were capable of understanding the inner workings of the defense industry.”31 The need for both military and civilian personnel to have experience with industry—which gives them a better understanding and appreciation of how technical decisions are made in industry, industry incentives, contract terms and conditions, and contract incentives—is an essential part of the Air Force’s ability to own the technical baseline.

CONCLUSION 5: Successful program managers have commonly held the following qualifications and career attributes: a technical degree in a STEM field, operational assignments, education in business management, experience in either a business setting or the Education with Industry program and a transition into an acquisition role no later than mid-career.32

___________________

29 Ibid.

30 Air Force Institute of Technology, Education with Industry Handbook, August 2009, p. 1, https://www.afit.edu/cip/docs/EWI_Handbook.pdf.

31 Ibid., p. 1.

32 The memorandum of the Under Secretary of defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics on key leadership positions and qualification criteria, dated November 8, 2013, stated that five factors had been identified as requirements essential for selection of key leadership positions for critical acquisition functions. The five requirements identified in the memorandum were education, experience, cross-functional competencies (executive leadership, program execution, technical management, and business management), tenure, and currency.

RECOMMENDATION 5: Air Force leadership should, in concert with its current activities,33 ensure that there is necessary guidance and governance for the currency of appropriate skills of the acquisition workforce at all levels. This must include, but is not limited to, emphasis on the criticality to program success of technically educated and technically experienced program managers. Additionally, the Air Force should prioritize education and experience in industry, recognize its importance to the development of competent acquisition personnel, and increase the opportunities for members of the acquisition workforce to gain this education and experience.

RECOMMENDATION 6: The Air Force should establish, select, and equip a dedicated line of program acquisition officers, selected from a defined science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM)-intensive career path in the uniformed services. This dedicated line of program acquisition officers would be similar in intent, education, and experience to the Navy’s engineering and aeronautical engineering duty officers. Additionally, a robust career path for USAF civilian engineers and program managers should be established that supports their critical importance to the successful execution of acquisition programs through ownership of the technical baseline. Program managers should generally be selected from the engineering and technical workforce.

The USAF supplements its organic technical workforce with on-site contractors who are not employed by the prime contractor of an acquisition program. These contractors, often hired via Advisory and Assistance Services (A&AS) contract vehicles, provide specific experience, education, certifications, and other skills to

___________________

33 This recommendation is in line with the memorandum of the Under Secretary of Defense Frank Kendall in “Implementation Directive for Better Buying Power 3.0—Achieving Dominant Capabilities through Technical Excellence and Innovation.” In the section “Establish stronger professional qualification requirements for all acquisition specialties,” this document says “This continues the BBP 2.0 effort in this area. The DAWIA [Defense Acquisition Workforce Improvement Act] experience requirements must be supplemented to establish a stronger basis for levels of professionalism across all acquisition career fields. The Department started the Acquisition Workforce Qualification Initiative (AWQI) in BBP 2.0 to better define qualification standards. The Department is close to completing the development of experiential/proficiency standards and tasks for each of the Acquisition Career Fields by competency and competency element. This career development tool focuses on the quality versus the quantity of the experience attribute of certification and provides a higher level of measureable demonstration of experience specific to a position. AWQI demonstrated experience standards will be distributed to the Acquisition Workforce (via the Components) as a guide to assist in Talent Management with an emphasis on career development and succession planning. It will aid in developing fully qualified acquisition professionals. The Components will be responsible for their implementation methodologies” (April 9, 2015, p. 29, http://www.acq.osd.mil/fo/docs/betterBuyingPower3.0(9Apr15).pdf).

fill gaps in the Air Force’s organic technical capabilities. One such vehicle for these services is the General Services Administration’s (GSA’s) One Acquisition Solution for Integrated Services (OASIS) contract. In a March 20, 2014, memorandum,34 the Air Force Life Cycle Management Center (AFLCMC) commander mandated the use within AFLCMC of the Engineering, Professional, and Administrative Support Services (EPASS) Program Management Office (PMO) for all A&AS requirements. The rationale was based on economic pressures and resource constraints, and an environment that required more efficacy and innovation. The memo further directed as follows:

The EPASS PMO will utilize the GSA OASIS [One Acquisition Solution for Integrated Services] Indefinite Quantity/Indefinite Delivery (ID/IQ) Multiple Award Contract (MAC) and will align their Labor Categories, which were developed as a best estimate of the labor required to support knowledge-based services across the federal government.

The OASIS contract uses North American Industry Classification System (NAICS)35 codes to define labor pools. Implementation challenges seem to persist from associating the broad NAICS codes (e.g., “541330—Engineering Services”) and OASIS “Pools” with the narrower EPASS labor categories (e.g., electronics engineer) and the associated specific personnel requirements. Overall, because the EPASS Program Office uses a technically acceptable, lowest evaluated price (TA/LEP) approach for selecting the contractor, OASIS task orders are awarded on a low-price basis to companies that may meet the NAICS codes but do not always have the more detailed and specific requisite skills to meet the requirements outlined by the program manager. Some PMs are provided with resources that cannot fill the defined technical gaps or meet the needs of the program.

CONCLUSION 6: OASIS task orders do not consistently meet program manager requirements and, in cases, appear to be cost-driven versus need-driven. The requirements defined by the program manager, and the technical capabilities of the personnel ultimately received, do not always align or are in conflict. This issue may reside in poorly defined requirements as provided by the program manager or in an inability to properly state requirements and fill them through the contract vehicle.

___________________

34 AFLCMC memorandum, “Policy for Mandatory Use of Engineering, Professional, and Administrative Support Services (EPASS) for Advisory & Assistance Services (A&AS),” March 20, 2014.

35 According to the U.S. Census Bureau website, “The North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) is the standard used by Federal statistical agencies in classifying business establishments for the purpose of collecting, analyzing, and publishing statistical data related to the U.S. business economy” (U.S. Census Bureau, “Introduction to NAICS,” last update August 8, 2016, http://www.census.gov/eos/www/naics/).

RECOMMENDATION 7: Air Force Life Cycle Management Center (AFLCMC) leaders should work with the Engineering, Professional, and Administrative Support Services (EPASS) program management office to put in place a rigorous requirements definition process such that specific technical requirements and criteria are approved by the program manager and that contractor personnel36 align with those requirements to meet the needs of the program. Application of AFLCMC’s technically acceptable, lowest evaluated price (TA/LEP) approach should be a secondary consideration to meeting the requirement and delivering customer value.

CONTRACTING SUPPORT

The roles of the program manager and the contracting officer are clearly delineated in existing DoD policy documentation. Acquisition reform and increased oversight, however, have helped to create an unintended consequence in which the two roles are sometimes upended, leading to poorly informed or rigid implementation of some contracting methodologies. The program manager is ultimately responsible for program outcome, and as such requires appropriate support from the other members of the government acquisition team.

As discovered in both the OTB Workshop report and during the study interviews conducted by the committee, the authorities and accountabilities of the PM as they relate to the authorities and accountabilities of the contracting officer (CO) are currently causing dysfunctional, as opposed to creative, tension, which is negatively impacting government acquisition team effectiveness in the Air Force. The committee could not find documentation that specifically addresses the necessary relationship between the PM and the CO, despite the fact that DoD 5000.0137 specifically defines the roles and authorities of the PM, and Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) documentation describes in clear terms the qualifications of and selection criteria for the CO. The FAR language does focus, however, on the importance of the government acquisition team, which includes both the PM and the CO, and the team’s collective obligation to adhere to performance standards. DoD 5000.01 also clearly states that the PM is the designated individual in terms of responsibility and authority for meeting program cost, schedule, and performance goals and for meeting the user’s operational needs. The PM, therefore, holds the ultimate responsibility for the management and technical direction of the program.

___________________

36 Contractor personnel refer to services purchased to augment the organic workforce within the program office.

37 DoD Directive Number 5000.01 provides management principles and mandatory policies and procedures for managing all acquisition programs (http://www.dtic.mil/whs/directives/corres/pdf/500001p.pdf).

The committee heard evidence that indicated the Air Force is having great difficulty rationalizing and de-conflicting certain aspects of the PM and CO roles. This has led to communication problems when selecting and executing efficient contracting strategies to meet mission requirements linked to the PM’s ability to own the technical baseline. This disconnect contributes to a continuing atmosphere of distrust between the contracting and program management communities and in some cases an adversarial relationship that is not conducive to a successful technical program. Government acquisition team performance, which is critical to contract implementation and mission success, is intimately tied to the relationship between these communities and their ability to communicate.

Interviewees commented on how the Air Force contracting community’s current approach to technical acquisition has fostered an atmosphere of top-down interference that increases the risk to program goals and objectives. Several PEOs and retired executives38 commented on the historical and current state of the relationship between Air Force program managers and contracting officers, citing “egregious behavior” on the part of contracting teams, and questioning their commitment to providing the best acquisition deal possible for the Air Force program. The PEO and PM perceptions were that, rather than coming to a resolution of conflicts that allows the program to proceed, these disputes over control of the program contribute to lengthy acquisition lead times, delay in contract negotiations, and a negative impact on the implementation of critical programs.

From the highest level, and in response to an excess of reform-driven oversight, the Air Force has undergone a bifurcation of the contracting community and program management community. Two chains of authority and decision making, which may be in conflict, have arisen and have replaced an effective working relationship between contracting personnel and PMs. Where PMs once actively learned about the culture and business philosophy of the contracting community through a “boots on the ground” perspective and COs learned the culture of the program management community from being an active member of the acquisition team, in many instances there is now a significant communication barrier separating the two communities.

There are agencies, services, and Air Force product centers where this bifurcation has not been as pervasive, such as the Missile Defense Agency and the Navy, and where success can be specifically attributed to documenting and clarifying the relationship between the PM and the CO from the very beginning of the program. The committee also learned of some exemplary ways in which the PM/CO relationships were pursued in successful Navy and NASA programs, both of which were characterized by clearly defined lines of responsibility that enabled people, infrastructure, and standards to function smoothly and in concert.

___________________

38 A full list of meeting participants can be found in Appendix C.

Program managers in the Navy and in large NASA programs typically have a technical background, but they are also versed in the art and science of program management, which are largely acquired through education, experience, and mentoring. The art aspect includes openly communicating with the COs and regarding them as valued members of the supporting team. Good relationships with contracting personnel, with responsibilities and requirements established clearly and at the beginning of the program effort, help to reduce the risk of post-contract litigation; excessive and time-consuming oversight; inaccurate or incomplete terms and conditions; and the diversion of resources for troubleshooting. Importantly, effective PEOs and PMs recognize when conflicts with the CO need to be taken to the next level, and how to escalate responses appropriately.

Lines of Authority

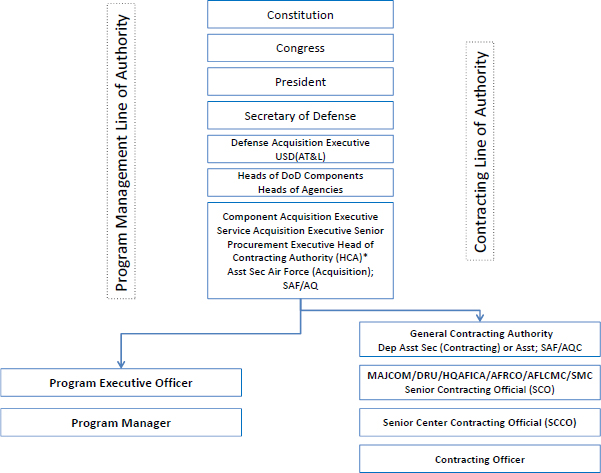

DoD 5000.01 establishes a clear program management line of authority (PM-LoA) that begins with the Defense Acquisition Executive (DAE) (Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics) and flows down to the PM. Paragraph 3-5 of the 5000.01 regulations speaks distinctly to specific PM roles and responsibilities, and DoD Instruction 5000.02 specifically delineates the PM’s role under the purview of the PEO.

FAR, DoD, and Air Force Supplements39 delineate the contracting line of authority (CLoA), which originates with the head of agency (i.e., the Secretary of the Air Force) and flows down to the CO.

As illustrated in Figure 3.4, the lines of authority diverge at the Assistant Secretary of the Air Force (Acquisition) level. Neither the DoD 5000 series documents nor the FAR and its supplements adequately address the functional interplay between the PM and CO roles and responsibilities. In many program offices, the head contracting executive is the chief of contracts, or someone with an equivalent title. The chief of contracts is the reporting official for the CO and is responsible for ensuring that the program receives high-quality support. Although the CO’s authority does not flow from the chief of contracting on a day-by-day basis, the chief sets the tone for how the designated program contracting staff supports the program. The chief also usually supports the PM’s staff meetings and acts as the PM’s business advisor. For purposes of this report, the term “contracting professionals” will include both the chief of contracting (if assigned) and the CO. Most PEOs and PMs understand the need for contracting professionals to provide an internal control for prudently following the appropriate contracting-related laws and policies since it is a responsibility driven by the FAR. However, the majority of acquisition decisions fall well

___________________

39 The supplements are the Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement and the Air Force Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement, respectively.

within those boundaries. Often an authority void exists regarding who has the final decision authority, which leads to dysfunctional tension, confusion, and frustration.

In the course of this study, some PEOs and PMs appeared reluctant to challenge COs on points that are clearly within the PM’s purview or to escalate the issue to the CO’s management. This reluctance on the part of PMs appears to stem from a lack of understanding of their authorities, or no effective escalation path for the issue, as well as past experiences gained from a culture of never challenging contracting officers. One example provided to the committee was that of a PM who was not allowed to attend Business Clearance and Contract Clearance sessions (AFFARS MP5301.9001(f)) because the CO insisted that the sessions were exclusively a con-

tracting management chain process. The Air Force Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (AFFARS) requires Business Clearance Approval and Office of the Secretary of Defense Peer Review approval to (1) establish negotiation objectives for competitive procurements or (2) establish final negotiation objectives before concluding negotiations for non-competitive procurements. The committee did not find any policy prohibiting PEO or PM representation at the clearance or Peer Review sessions.

CONCLUSION 7: In many cases, there is confusion, frustration, miscommunication, and mistrust in the relationship among the COs and the PEOs and PMs they support. The committee found evidence that in some instances, contracting professionals (1) overstep their authority (for example, by dictating a specific contracting approach), (2) apply overly strict and restrictive interpretations of regulations, (3) take positions on business issues without providing adequate explanation to the rest of the government acquisition team (FAR 1.102-3), and (4) are not evaluated via their annual appraisals based on the quality of their support to the program manager, successful program execution, or meeting program office objectives within FAR guidelines.

CONCLUSION 8: The Air Force does not currently possess an adequate program management governance structure that specifies clear lines of authority, responsibility, and accountability for members of the government acquisition team. Additionally, Air Force PEOs and PMs are not mandatory participants in Business Clearance or Contract Clearance sessions, even though the negotiation objectives, key contract terms and conditions, and the nature of the deal are largely set in these sessions. Without a full awareness of contract terms and objectives, PMs and PEOs may find themselves in a position of being forced to implement an acquisition approach or execute a contractual business arrangement that they either do not understand or believe to be inappropriate.40

___________________

40 Page 27 of the Under Secretary of Defense’s memorandum of April 9, 2015, “Implementation Directive for Better Buying Power 3.0—Achieving Dominant Capabilities through Technical Excellence and Innovation,” states under the “Improve requirements definition for services” section that “Improving services contracting requirements definition is a continuing BBP [better buying power] initiative. Defining requirements well is a challenging but essential prerequisite in achieving desired services acquisition outcomes. As most services are integrated into the performance of a mission, it is critical to get the mission owner (often an operational commander) involved in the requirement definition, as well as the acquisition and execution phases. Continuous involvement through the services acquisition phases will lead to improving requirements definition for future acquisitions” (http://www.acq.osd.mil/fo/docs/betterBuyingPower3.0(9Apr15).pdf).

RECOMMENDATION 8: The Air Force should issue a guidance memorandum that clearly specifies the lines of authority and accountability for all members of the government acquisition team.41 This memorandum should clarify and reinforce program manager (PM) authorities and responsibilities as well as specify contracting officer responsibilities, as part of the government acquisition team, in relation to the PM. Specifically, all functional entities should provide the PM with the support necessary to attain program success. All members of the government acquisition team should be measured based on program success while complying with the law. Additionally, the Air Force should revise the Air Force Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement to make it clear that Air Force program executive officers and PMs, or their designated representatives, are mandatory participants in business clearance and contract clearance sessions. Program management and contracting personnel should be trained in implementation of the guidance.

During the OTB workshop, several program offices expressed frustration that the contracting office is not accountable for program success or failure and is focused on aspects that are taken out of context with the overall program. This lack of program accountability creates a disparity in incentives between the PM, who needs the technical support, and the CO, who is focused on process issues and timelines. COs who are not held accountable for program success, yet have the authority to constrain the PM from hiring the best engineering talent to support the program, often use cost control as the paramount metric, thus subverting the necessary balance among cost, schedule, and technical scope. CO mandates that a specific contract vehicle type be used (e.g., lowest price, technically acceptable [LPTA] for acquiring S&E support) can preclude the PM from hiring highly skilled engineering talent (and have done so). This relationship is a pressing issue for the Air Force to address in order to give the PM access to the technical expertise necessary to own the technical baseline.

___________________

41 This recommendation is in line with the Under Secretary of Defense’s memorandum, “Implementation Directive for Better Buying Power 3.0—Achieving Dominant Capabilities through Technical Excellence and Innovation,” under the section “Eliminate Unproductive Processes and Bureaucracy” and the subsection “Emphasize acquisition chain of command responsibility, authority, and accountability.” This section states “This initiative is a continuing effort from BBP 2.0. The chain of command for acquisition programs runs upward from the [program manager] through the [program executive officer] to the [component acquisition executive] and, for [Acquisition Category] ACAT I, ACAT IA, and other programs so designated, to the [defense acquisition executive]. The responsibility and authority for program management, to include program planning and execution, is vested only in these individuals. Staff and other organizations provide support to this chain of command” (April 9, 2015, p. 18, http://www.acq.osd.mil/fo/docs/betterBuyingPower3.0(9Apr15).pdf).

CONCLUSION 9: Not all government acquisition team members are currently accountable for program progress, success, or failure, and the primary objectives and requirements of the program manager and contracting officer are disconnected or in some cases appear to be in opposition to one another, creating disparity in effort and incentives.

RECOMMENDATION 9: Contracting professionals’ appraisals should have appropriate objectives and metrics tied directly to the program office or organization’s mission success. The program executive officer or the program manager or their designee should be required to provide written performance input to the contracting professionals’ annual appraisals. Contracting professionals should engage with the program office and be well trained and experienced with their accountability and responsibility for delivering support to the assigned Air Force organization and mission.

The above issues between program officers and contracting officers have contributed to an ongoing erosion of trust and, in several cases, an adversarial relationship between the PM and CO, which has proven highly detrimental both to the acquisition process and to meeting mission needs.

Lowest Price, Technically Acceptable

During the data-gathering meetings, the committee heard several examples of dissatisfaction with the indiscriminate use of the LPTA source selection as a contracting methodology. LPTA is a process that is one of the methodologies contained in what FAR 15.101 describes as the “Best Value Continuum,” defined by the FAR as follows:

An agency can obtain best value in negotiated acquisitions by using any one or a combination of source selection approaches. In different types of acquisitions, the relative importance of cost or price may vary. For example, in acquisitions where the requirement is clearly definable and the risk of unsuccessful contract performance is minimal, cost or price may play a dominant role in source selection. The less definitive the requirement, the more development work required, or the greater the performance risk, the more technical or past performance considerations may play a dominant role in source selection.

“Better Buying Power 2.0” contained the following guidance:

When LPTA is used, define Technically Acceptable to ensure needed quality: Industry has expressed concerns about the use of Lowest Price, Technically Acceptable (LPTA) selection criteria that essentially default to the lowest price bidder, independent of quality.

Where LPTA is used, the Department needs to define TA appropriately to ensure adequate quality.42

During the OTB workshop, participants noted instances of inappropriate use of LPTA, where the government acquisition team would have been better served by using a more integrated and best-value approach to enhance the ability to tradeoff between non-cost factors to ensure the selected contractor could meet requirements. LPTA is an evaluation for a specific point in time and does not possess metrics for forecasting impacts at various program stages. Another major concern heard during interviews for both the OTB workshop and this study was that the LPTA methodology does not allow for consideration of the specific engineering expertise, skills, and experience criteria needed to provide high-quality and specific technical resources—items paramount to owning the technical baseline. It appeared that some of the existing contracts and task orders awarded using LPTA methodology were written to accommodate a larger group of contract awardees, including small businesses, and to save money through a simpler source selection process and artificially suppressed contractor labor rates, as opposed to keeping the focus on quickly and efficiently hiring proficient, competent technical contractor resources.

A highly technical organization such as NASA does in fact employ contracting vehicles that are as simple as a one-page letter of agreement, characterized by a director-level contracting team engaged in long-term strategizing, case-by-case intellectual property sharing, and joint cost-sharing activities. Programs need flexibility to adopt a more nuanced approach than LPTA to provide unique solutions for solving technical problems.

CONCLUSION 10: The LPTA contract type was not intended to be mandatory or for the acquisition of all technical products and systems, but it has evolved in that direction in the current acquisition climate. Indiscriminate use of LPTA as a proposal evaluation and contractor selection methodology has resulted in poor outcomes and frustrated program managers, who do not receive the required high-quality technical support that is required for understanding and owning the technical baseline. When not used properly, LPTA can result in a lack of technical and engineering expertise. It can lead to an inadequate mix of talents for the contract, cause long delays in the process of contract execution, and create excessive turnover in the workforce owing to low wages.

___________________

42 Under Secretary of Defense, “Better Buying Power 2.0: Continuing the Pursuit for Greater Efficiency and Productivity in Defense Spending,” Memorandum for Defense Acquisition Workforce, November 13, 2012, http://bbp.dau.mil/doc/USD-ATL%20Memo%2013Nov12%20-%20BBP%202.0%20Introduction.pdf, p. 5.

RECOMMENDATION 10: The Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Acquisition should clarify the criteria for use of the lowest price, technically acceptable (LPTA) methodology and ensure there are avenues for the government acquisition team to discuss its appropriateness for meeting mission requirements. LPTA should not be applied to complex, multiyear, multidiscipline programs or knowledge-based service contracts that require high-end acquisition and technical talent. A decision to use LPTA should depend on clear and unambiguous requirements, underlying market research, and relevant information acquired during government and contractor interactions, such as “industry days.” If there is a requirement that demands special treatment, the case should be made in the requirements definition, acquisition strategy, and pre-request for proposal activity.

In the case of contracting, OTB will enable the government acquisition team to make smart decisions, facilitate contracting trade-offs, and enhance its overall ability to implement the contract. Regaining the OTB could enable the USAF to carry out contracting activities in an efficient and timely manner through informed decision making.

FUNDING

In a constrained budgetary atmosphere, the efficient use of available funds to support weapons systems is paramount to meeting mission requirements. Air Force leaders have recognized this need and have already begun to employ more flexible means of funding acquisition staff. Of even greater concern, however, is the need to recognize that the Air Force cannot accept new programs without the ability to execute them.

As was initially discussed during the OTB workshop and reaffirmed throughout the study, the type of funds used for personnel is a key issue. Funding is a key variable for hiring top-shelf engineers from academia or industry and supporting their advanced education and training in core competencies and providing mentors to guide their careers through increasing levels of responsibility such that these engineers fulfill the needs of PEOs and PMs charged with executing programs. A lack of adequate and timely funding will continue to limit the ability of acquisition center functionaries to create a workforce that is capable of meeting the high technical demands of Air Force weapon systems.

The committee heard evidence that the Air Force was already in the process of realigning funding for development of the acquisition workforce.43 The use of

___________________

43Appendix D contains a memorandum from the Commander of AFLCMC to the study committee that highlights current activities at AFLCMC.

research, development, testing, and evaluation (RDT&E) funding (“3600” funds) instead of operations and maintenance (O&M) funding (“3400” funds) is already in the process of being used to fund the acquisition workforce. This move, it is widely believed, will allow more flexibility in the hiring and training of the organic engineering workforce. The use of 3600 funding would allow civil service engineers to be secured, trained, and employed in support of program office needs and to fill the necessary gaps.

CONCLUSION 11: Lack of adequate and timely funding limits the ability of acquisition-center functional leads to shape the workforce to meet the demand for knowledgeable and experienced technical talent.44

RECOMMENDATION 11: The Air Force should complete the shift from operations and maintenance funds to research, development, testing, and evaluation funds for funding acquisition staff. Additionally, the Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Acquisition should require program managers to include in their program financial plan such a budget, as necessary, to fully fund the in-house technical effort.

The committee heard additional evidence of other Air Force efforts to address funding issues that relate to the Air Force’s ability to own the technical baseline of its acquisition programs. One such effort was the pursuit by the Air Force to utilize the flexibility provided by the Air Force Working Capital Fund (AFWCF).45 The AFWCF would facilitate PM use of in-house engineering staff to facilitate the technical work necessary to own the technical baseline. This would be done by expanding the use of the AFWCF from its current applications in logistic support. While the committee did not receive enough information on the Air Force’s current efforts to utilize the AFWCF to make a recommendation, the committee notes its value to owning the technical baseline. The committee also heard evidence of problems arising from a lack of proper resourcing, as required by the Weapons Systems Acquisition Reform Act (WSARA) of 2009, of new major defense acquisition programs (MDAPs).46 Starting new programs without adequate funding significantly hampers the Air Force’s ability to own the technical baseline of its programs. Budget cuts to established MDAPs during the yearly planning, pro-

___________________

44 This conclusion was also a major recurring theme in National Research Council, Owning the Technical Baseline for Acquisition Programs in the U.S. Air Force: A Workshop Report, The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C., 2015, p. 4.

45 General Ellen M. Pawlikowski, Commander, Air Force Materiel Command, interview with the committee on March 23, 2016.

46 Lynn M. Eviston, Director of Plans and Programs, Air Force Life Cycle Management Center, interview with the committee on March 31, 2016.

gramming, budget, and execution (PPBE) process can cause the Air Force to lose ownership of the technical baseline in programs where it once had had ownership. The Air Force, as highlighted previously in the Workforce Management section, is over-programmed. Inadequate funding for programs results in elongated delivery schedules and difficulties in achieving cost, schedule, and performance goals.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Tomorrow’s wars are being fought in today’s program development offices. To win those wars, urgent and dramatic steps are needed to ensure that the Air Force removes several major barriers to success. Owning the technical baseline is a critical component of the Air Force’s ability to regain and maintain acquisition excellence. There are definitely very professional PEOs and PMs who are performing well in spite of the barriers, but it is clear that the USAF needs to take immediate steps to emphasize the value of its acquisition professionals, ensure sustained leadership within the acquisition community, reinforce the PM’s authority and accountability, clarify the role of the contracting officer vis-à-vis the PM, strengthen and expand the technical knowledge base and expertise of the acquisition workforce, and continue to eliminate barriers and avoid creating new ones. These necessary steps for owning the technical baseline are especially important in light of the shorter and shorter time frames within which the Air Force needs to develop and deploy warfighting capabilities to meet rapidly emerging and changing threats.

This page intentionally left blank.