Summary

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and other health care payers have increasingly moved from traditional, fee-for-service payment models to value-based payment (VBP), which aims to improve quality and efficiency, while also controlling costs. Although this focus on improving health care outcomes has led providers to address social risk factors in the delivery of health care, current VBP design generally does not account for the role of social risk factors in producing health care outcomes. This has led to concerns that the trend toward VBP could result in certain adverse consequences for socially at-risk populations, such as leading providers and health plans to avoid patients with social risk factors, underpayment of providers disproportionately serving socially at-risk populations (e.g., safety-net providers), and thus exacerbating health disparities.

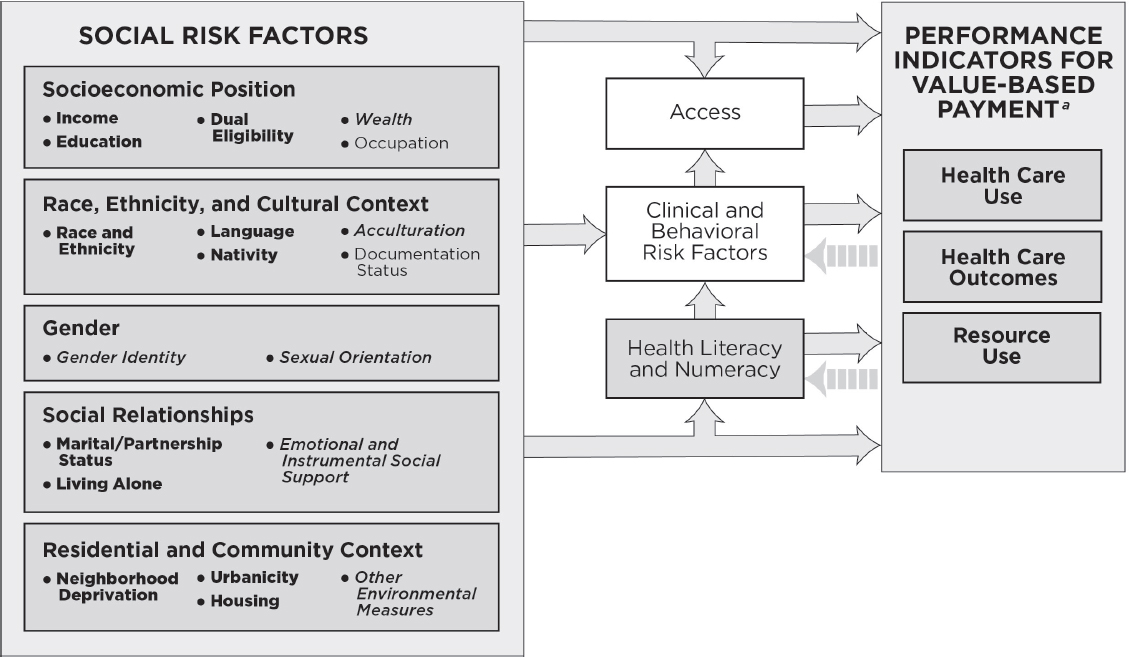

Some have proposed accounting for social risk factors in quality measurement and payment as a way to address the negative consequences of the status quo. Accounting for social risk factors extends the logic of clinical risk adjustment, which accounts for underlying clinical risk factors that can independently drive variation in performance and may differ systematically across providers, and which can therefore statistically bias measured performance, to also include social risk factors. The committee identified five domains of social risk factors—(1) socioeconomic position; (2) race, ethnicity, and cultural context; (3) gender; (4) social relationships, and

(5) residential and community context—that are associated with health care outcomes independently of quality of care.

Accounting for social risk factors can achieve important policy goals. It can align incentives to reduce disparities and improve quality and efficiency both for socially at-risk populations and overall. It can also improve fairness and accuracy in reporting and compensate providers fairly without obscuring true differences in quality among providers. Accounting for social risk factors is complex and recommending whether CMS should account for social risk factors is beyond the scope of the committee’s task, but the committee provides guidance on what CMS could do if they choose to do so. Specifically, the committee details how to choose factors to include in Medicare VBP and which factors one might start with. Once the factors are selected, there are several ways to account for them, and a combination of methods, including both payment and public reporting, are likely needed to achieve policy goals while also mitigating risks. Indicators, data, and methods exist to account for social risk factors now; in addition, the committee recommends that the government collect data and develop methods, measures, and models for improved use in VBP. Finally, even after social risk factors are accounted for in VBP, providers need knowledge about how to improve care for populations with these factors, and the committee provides a framework on how to approach this. Research, monitoring, and quality improvement interventions can help ensure that accounting for social risk factors in VBP does not increase health disparities.

It is possible to deliver high quality care to socially at-risk populations, but it is harder on average and costs money, and providers who disproportionately serve socially at-risk populations frequently have fewer resources. It is also possible to improve on the status quo with respect to the effect of VBP on socially at-risk populations, although it is important to minimize potential risks to patients with social risk factors and to monitor any specific approach to accounting for social risk factors to ensure that unanticipated adverse effects on health disparities do not emerge.

Equity is a critical aim of any high-performance health system (IOM, 2001; NASEM, 2016d). Health equity can be conceptualized at the level of a health care system or more broadly at the population level (IOM, 2001). Equitable health care represents a commitment by providers and payers to provide a universally high standard of health care quality to all patients and enrollees regardless of their individual characteristics (NASEM, 2016b). Achieving this may require greater resources and more intensive care for

patients with social risk factors compared to more advantaged patients. At the population level, health equity is an ethical value that promotes improvement in health status for all individuals (Braveman and Gruskin, 2003; IOM, 2001). Because achieving the same health care outcomes, health status, or health improvements may require remediating deep social inequalities in social risk factors such as inadequate housing or food insecurity, providing equitable health care is unlikely to be sufficient on its own to achieve health equity at the population level (NASEM, 2016b,c). Although providers can address and mitigate the effects of social risk factors (NASEM, 2016c), when social risk factors are not accounted for in performance measurement and payment in the health care system, achieving performance benchmarks (i.e., good outcomes) may be more difficult for providers disproportionately serving socially at-risk populations owing to the influence of social risk factors.

One lever to achieve high-performance health systems, including one that promotes equity, is through payment (IOM, 2001). When payment strategies are aligned with policy goals, such as improving quality and efficiency in health care or reducing disparities, payment can help incentivize these goals. When payment strategies and policy goals are misaligned, payment can act as a barrier (IOM, 2001). Reforms to better align payment with policy goals shift from paying for volume (fee-for-service) to paying for quality, also known as value-based payment (VBP). Specifically, VBP programs aim to improve the quality of care and efficiency of delivering care, while also controlling costs (Burwell, 2015; Rosenthal, 2008). The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and other health care payers have increasingly moved from traditional, fee-for-service payment models to VBP payments and are continuing to do so at a rapid rate (Burwell, 2015). Although VBP programs have catalyzed health care providers and plans to address social risk factors in health care delivery through their focus on improving health care outcomes and controlling costs, the role of social risk factors in producing health care outcomes is not generally reflected in payment under current VBP design. This misalignment has led to concerns that trends toward VBP could result in tangible harms to socially at-risk populations. Providers disproportionately serving socially at-risk populations are more likely to score poorly on performance/quality rankings, more likely to be penalized, and less likely to receive bonus payments under VBP. VBP may be taking resources from the organizations that need them the most (Chien et al., 2007; Ryan, 2013).

One proposal to address the documented harms of the status quo under current VBP is to account for social risk factors in quality measurement and/or payment. Currently, to ensure accurate comparisons, VBP models account for underlying clinical risk factors known to independently drive variation in performance and to differ systematically across providers

and therefore could statistically bias measured performance. Proposals to account for social risk factors extend the rationale of accounting for clinical risk factors in performance measurement and payment by also including social risk factors as underlying patient characteristics that independently influence performance indicators and that differ systematically across providers and thus lead to bias in measured performance.

Proponents of this method cite the unintended consequences of the status quo—disproportionate penalties on providers serving socially at-risk populations and incentives to avoid patients with social risk factors. Opponents argue that providers should be held accountable for providing care that mitigates the effect of social risk factors on health care outcomes. Proponents of accounting for social risk factors might counter that because social risk factors are difficult to address through provider action, providers should not be held accountable for them (Boozary et al., 2015; Feemster and Au, 2014; Fiscella et al., 2014; Girotti et al., 2014; Jha and Zaslavsky, 2014; Joynt and Jha, 2013; Lipstein and Dunagan, 2014; Pollack, 2013; Renacci, 2014).

STATEMENT OF TASK

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) acting through the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) contracted with the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to convene an ad hoc committee to prepare a series of five brief reports that aim to inform ASPE analyses that account for social risk factors in Medicare payment programs mandated under the Improving Medicare Post-Acute Care Treatment (IMPACT) Act. In the first report, the committee presented a conceptual framework and described the results of a literature search linking five social risk factors and health literacy to health-related measures of importance to Medicare quality measurement and payment programs. In the second report, the committee reviewed the performance of providers disproportionately serving socially at-risk populations, discussed drivers of variations in performance, and identified six community-informed and patient-centered systems practices that show promise to improve care for socially at-risk populations. The committee’s third report identified social risk factors that could be considered for inclusion in Medicare quality measurement and payment, criteria to identify these factors, and methods to account for them in ways that can promote health equity and improve care for all patients. The fourth report provides guidance on where to find and how to collect data on social risk factor indicators that could be used for Medicare quality measurement and payment programs. In this fifth and final report, the committee aims to put the entire series in context and offers additional thoughts about how to best

consider the various methods for accounting for social risk factors, as well as next steps. Notably, it is beyond the committee’s task to recommend whether social risk factors should be accounted for in Medicare VBP. The committee’s reports detail what the ASPE and CMS could do if they choose to do so. Details of the statement of task and the sequence of reports can be found in Chapter 1. Reports 1–4 are reproduced in their entireties in Appendixes A–D.

THE COMMITTEE’S GOALS

The committee emphasizes that any approach to accounting for social risk factors should do so in a manner that can improve care and promote equity for all patients, especially those with social risk factors. As presented in its third report (NASEM, 2016b), the committee’s four goals in accounting for social risk factors in Medicare payment programs are

- Reducing disparities in access, quality, and outcomes;

- Quality improvement and efficient care delivery for all patients;

- Fair and accurate reporting; and

- Compensating providers fairly.

Any approach to account for social risk factors (including the status quo, which generally does not account for social risk factors) will achieve important policy goals, but could also have unintended consequences. The committee identified five categories of potential unintended consequences:

- Avoiding patients with social risk factors

- Reducing incentives to improve the quality of care for patients or enrollees with social risk factors

- Underpayment to providers disproportionately serving socially at-risk populations

- Negative symbolic value: perceptions of different standards for different populations

- Obscuring disparities

SOCIAL RISK FACTORS AND INDICATORS

The committee first developed a framework by which social risk factors might influence health care outcomes of interest to Medicare’s VBP programs. Each social risk factor has a conceptual and an empirical association with those outcomes and could be included as adjustments to Medicare VBP. The committee further identified one or more indicators for each social risk factor that meet the committee’s criteria of having a relationship

to health care outcomes of interest, preceding care delivery and not being a consequence of the quality of care, not being something the provider can manipulate, and also meeting practical considerations. The rationale for the criterion that a social risk factor is not modifiable through provider actions aims to exclude factors that reflect genuine differences in the quality of care. Whether a social risk factor is modifiable or unmodifiable is not binary, but rather describes a spectrum of effects. Thus, it can be challenging to identify where a given social risk factor lies on this spectrum, particularly as health care providers and plans are increasingly addressing social risk factors for poor health outcomes. It is critical to distinguish between factors that can be modified themselves and factors that are not modifiable themselves, but whose effects on health can be mitigated through provider actions (such as use of tailored interventions) without altering the underlying disadvantage. The text that follows includes a brief description of the social risk factors. Note, the listing of social risk factors does not reflect an order of priority. See Figure S-1 for the conceptual framework and the indicators identified by the committee.

As described in the committee’s first report (NASEM, 2016a), the committee prefers socioeconomic position (SEP) to the more common phrase socioeconomic status, because socioeconomic position is a broader term encompassing resources as well as status (Krieger et al., 1997). SEP reflects a person’s absolute and relative position in a socially stratified society, and captures a combination of access to material and social resources, as well as relative status (i.e., prestige- or rank-related characteristics).

Race and ethnicity are related but conceptually distinct constructs that are dimensions of a society’s stratification system by which resources, risks, and rewards are distributed. In particular, race and ethnicity capture features of social disadvantage, including access to social institutions and rewards; behavioral and other sociocultural norms; inequality in the distribution of power, status, and material resources; and psychosocial exposures (IOM, 2014; Williams, 1997). Constructs of cultural context include language and nativity.

The term gender captures social dimensions of gender as distinguished from biological effects of sex and encompasses both normative and nonnormative (e.g., transgender) gender identity. Normative gender categories (men and women) are included in clinical risk adjustments in Medicare. Sexual orientation includes individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, questioning, or otherwise nonconforming. Sexual orientation is typically defined with respect to three dimensions: attraction, behavior, and identity (IOM, 2011).

Social relationships are important for health because they provide access to social networks that can provide access to resources (including instrumental support and access to health care services or health-promoting

resources), as well as emotional support (Berkman and Glass, 2000; Cohen, 2004; Eng et al., 2002; House et al., 1988). Social relationships are most frequently assessed in the health care and health services research literature with three constructs: marital/partnership status, living alone, and social support.

Residential and community context captures a set of broadly defined characteristics of residential environments, including compositional characteristics that describe aggregate characteristics of individuals residing in a given neighborhood or community, as well as characteristics of social and physical environments.

DATA SOURCES

The committee identified three sources of data on social risk factors for possible use by CMS: (1) new and existing sources of CMS data, (2) data from providers and plans, and (3) alternative government data sources.1 Existing sources of CMS data include administrative records (enrollment records and claims data) and beneficiary surveys with limited social risk factor data, such as race and ethnicity (ResDAC, n.d.). CMS could also collect new data on social risk factors, such as through a new administrative form or beneficiary survey. The committee recognizes the substantial barriers of collecting new data, including cost and burden. However, accounting for social risk factors could mitigate adverse consequences of the current VBP and therefore could justify the expected costs and burden of new data collection. Such data collection will also facilitate monitoring for potential unintended consequences of accounting for social risk factors in VBP on health disparities.2

Data from providers and plans include electronic health record (EHR) data and administrative data that providers and plans send to CMS. Some social risk factor data (for example, race and ethnicity and language) is already captured in some EHRs and some administrative data (e.g., IOM, 2014). New social risk factor data that providers and plans could collect could also be important for the care or services providers and plans provide (IOM, 2014).

Alternative government data refer to administrative data and national surveys that federal agencies other than CMS (including other agencies within HHS) and state agencies oversee and maintain that contain informa-

___________________

1 Social risk factor data could also be obtained from private data sources, but because these sources and their data collection methods are not fully transparent and because CMS would have to purchase this data at unknown cost, the committee deemed use of such private data as out of scope.

2 See Conclusion 4 in the committee’s third report (NASEM, 2016b).

NOTE: This conceptual framework illustrates primary hypothesized conceptual relationships. For the indicators listed in bullets under each social risk factor, bold lettering denotes measurable indicators that could be accounted for in Medicare VBP programs in the short term; italicized lettering denotes measurable indicators that capture the basic underlying constructs and currently present practical challenges, but are worth attention for potential inclusion in accounting methods in Medicare VBP programs in the longer term; and plain lettering denotes indicators that have considerable limitations.

a As described in Figure 1-1, health care use captures measures of utilization and clinical processes of care; health care outcomes capture measures of patient safety, patient experience, and health outcomes; and resource use captures cost measures.

tion on social risk factors and that CMS could use. These include data that could be linked to Medicare beneficiary data at the individual level as well as area-level data that could be used to describe a Medicare beneficiary’s residential environment or serve as a proxy for individual-level effects. The Social Security Administration may be the best source of individual-level social risk factor data that could be linked to Medicare beneficiary data. The American Community Survey may be most useful as a source of area-level social risk factor data.

After considering data sources for each social risk factor with respect to three characteristics (collection burden, accuracy, and clinical usefulness), the committee recommended specific data CMS could use to account for social risk factors in Medicare VBP if it so chooses. The committee also recommended that CMS should collect information about relevant, relatively stable social risk factors, such as race and ethnicity, language, and education, at the time of enrollment.3Table S-1 summarizes the availability of data for social risk factor indicators.4

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS ABOUT SOCIAL RISK FACTOR INDICATORS

Upon release of the committee’s prior reports, several questions arose about specific risk factors in the committee’s framework and about the discussions of data sources. The committee addresses these here.

The committee has found compelling reasons for considering each indicator listed for inclusion in Medicare quality and measurement programs and makes no distinctions in terms of which social risk factor or indictor is “most important” from either a conceptual or empirical standpoint. Table S-1 is meant to convey “readiness” for use of any specific indicator, not a prioritization or preference. For example, theory suggests that sexual orientation and gender identity may contribute to health disparities experienced by Medicare beneficiaries who identify as gender or sexual minorities (IOM, 2011; NASEM, 2016a,b). Although there are best practices for collecting data on gender identity and sexual orientation, there are no standards (NASEM, 2016c). Consequently, there remains little information on the effect of sexual orientation and gender identity on performance indicators used in VBP. The committee recommended that, as such evidence emerges, CMS should revisit inclusion of these indicators in Medicare quality measurement and payment programs.

In addition to the five domains of social risk factors, the committee also considered the influence of health literacy on performance indicators

___________________

3 See Recommendation 7 in the committee’s fourth report (NASEM, 2016c).

4 See Recommendations 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 in the committee’s fourth report (NASEM, 2016c).

TABLE S-1 Summary of Data Availability for Social Risk Factor Indicators

| SOCIAL RISK FACTOR | DATA AVAILABILITY | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| SEP | |||||

| Income | |||||

| Education | |||||

| Dual eligibility | |||||

| Wealth | |||||

| Race, Ethnicity, and Cultural Context | |||||

| Race and ethnicity | |||||

| Language | |||||

| Nativity | |||||

| Acculturation | |||||

| Gender | |||||

| Gender identity | |||||

| Sexual orientation | |||||

| Social Relationships | |||||

| Marital/partnership status | |||||

| Living alone | |||||

| Social support | |||||

| Residential and Community Context | |||||

| Neightborgood deprivation | |||||

| Urbanicity/rurality | |||||

| Housing | |||||

| Other environmental measures | |||||

![]() Available for use now

Available for use now

![]() Available for use now for some outcomes, but research needed for improved, furure use

Available for use now for some outcomes, but research needed for improved, furure use

![]() Not sufficiently available now; research needed for improved, future use

Not sufficiently available now; research needed for improved, future use

![]() Research needed to better understand relationship with health care outcomes and on how to best collect data

Research needed to better understand relationship with health care outcomes and on how to best collect data

used in Medicare VBP, because it is specifically mentioned in the committee’s task. It is also included in the IMPACT Act of 2014. The committee does not consider health literacy to be a social risk factor, but rather a more proximal risk factor that is influenced by (more distal) social risk factors. Specifically, health literacy can be considered the product of an individual’s skills and abilities (including reading and other critical skills), sociocultural factors, education, health system demands, and the health care context (IOM, 2004). Exclusion of health literacy in the social risk factor framework and the discussions of data sources should not be interpreted as a lack of appreciation for the contribution of health literacy to health and health care outcomes.

The committee considers disability to be a proximal risk factor for poor health care outcomes that is influenced by more distal social risk factors, somewhat like health literacy. The World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health advocated in the 2007 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report The Future of Disability in America conceives of disability not as an inherent attribute of individuals, but rather the product of individual capacities (health conditions) and social conditions (including social and physical environments) (IOM, 2007b; WHO, 2001). Some current clinical risk adjustment systems capture disability as an origin of Medicare entitlement. Additionally, clinical risk factors included in existing Medicare VBP clinical risk adjustments capture clinical elements of disability through major clinical diagnoses. Accounting for social risk factors could capture additional risk unmeasured by clinical risk factors not currently accounted for in Medicare payment programs. The committee acknowledges that disability can be differentiated from some clinical risk factors because of increased stigma, which may result in discrimination and other barriers to adequate health care. However, the committee notes that many clinical and behavioral diagnoses—for example, mental health and substance use disorders—are also stigmatized. Additionally, these types of barriers are consequences of the quality of care and therefore are not appropriate adjustors because they reflect true differences in the quality of care.

METHODS TO ACCOUNT FOR SOCIAL RISK FACTORS

In its third report (NASEM, 2016b), the committee identified 10 methods in 4 categories that could be used individually or in combination to account for social risk factors. These categories are

- Stratified public reporting;

- Adjustment of performance measure scores;

- Direct adjustment of payment; and

- Restructuring payment incentive design.

Stratified public reporting, adjustment of performance scores, and direct adjustments of payment build on the existing payment system. Restructuring incentive design presents entirely new approaches. Any approach to accounting for social risk factors will interact with the underlying incentive design to achieve certain policy goals or produce certain adverse consequences. As the committee concluded, strategies to account for social risk factors for measures of cost and efficiency may differ from strategies for quality measurement, because observed lower resource use may reflect unmet need rather than the absence of waste, and thus lower cost is not always better, while higher quality is always better (NASEM, 2016b).5

The committee provides specifics examples and methods for accounting for social risk factors and underscores the differences in the goals of each approach that guide their applications. Stratified public reporting aims to allow a decision maker (e.g., patient) to observe and act on differences in performance for different types of patients. Similarly, adjustment of performance measure scores affects what patients observe about the performance of a provider or health plan and CMS. On their own (that is, without stratified data), adjusted scores by definition send a single performance signal that accounts for differences in the mix of patients served but does not make disparities apparent. In contrast, adjusting payment algorithms (through either the third or fourth category of methods) is intended to alter the incentives for the plan or provider directly. The reliability of those measures will affect the balance of incentives and risk inherent in the payment formula: noisy measures impose risk and diminish the returns to improvement efforts.

Public reporting aims to make quality of care and outcomes visible to consumers, providers, payers, and regulators (IOM, 2007a). Provision of quality information to these stakeholders can lead to quality improvement for all beneficiaries through reputational incentives and by increasing market share (i.e., influencing beneficiaries’ choice of provider or plan) for reporting units (i.e., the hospital, health plan, etc. reporting performance information to CMS) with higher performance (IOM, 2007a). Stratified public reporting provides this information for specific subgroups and thus could lead not only to quality improvement, but also disparities reduction. Just as overall performance can lead to quality improvement for all beneficiaries, publicly reported performance scores stratified by social risk factors could influence beneficiaries’ choices by allowing patients to see which providers or plans provide the best care for patients like them. Because public reporting with stratification by patient characteristics within reporting units is the only method that presents information on subpopulations and can therefore highlight any disparities that may exist, it is also the only method

___________________

5 See Conclusion 7 in the committee’s third report (NASEM, 2016b).

that would allow CMS to monitor disparities. Thus, if monitoring disparities is an important policy goal, any approach to account for social risk factors must include public reporting stratified by patient characteristics within reporting units.

Adjusting performance measure scores aims to estimate the true quality of reporting units (i.e., the quality a reporting unit would have if all units had the population average patient). Such adjustment aims to statistically minimize the effect of factors, such as social risk factors, that may independently influence performance indicators used in VBP. The current system generally does not take these factors into account. Because social risk factors should no longer have substantial influence on performance measure scores, accurate adjustment would reduce incentives to avoid patients with social risk factors. Incorrect adjustment of performance measure scores could produce several potential unintended consequences. In particular, adjusting for between-provider differences may conflate differences that arise from patient characteristics and true differences in quality, because it may capture not only the measured patient characteristic (e.g., low income), but also the unmeasured influence of a provider or plan characteristic linked to overall quality. Thus, accounting for between-provider differences would remove incentives to improve care, especially for patients with social risk factors. This is a serious disadvantage that CMS would want to consider carefully. Adjustment for within-provider differences is less subject to this concern, because it accounts for differences between subpopulations within a provider (e.g., subgroups with high and low levels of social risk factors). Although adjusting performance measure scores for within-provider differences creates an estimate of the average disparity within providers, neither the magnitude of this disparity nor subgroup performance are apparent in the publicly reported performance scores. Even if both adjusted and unadjusted performance scores are publicly reported, only whether a provider is doing better or worse relative to the average disparity is visible. Thus, this method does not make disparities visible unless it is combined with public reporting stratified by patient characteristics within reporting units.

Direct adjustment of payment refers to any adjustment in payment with no adjustment of performance measure scores. This could be done by adjusting the payment formula (CMS, 2015) or by setting different benchmarks for payment for different strata of social risk factors (Damberg et al., 2015). By accounting for the increased resources (i.e., estimated costs) needed to care for socially at-risk populations, directly adjusting payments avoids unintentionally redistributing resources away from (i.e., underpaying) providers who serve patients with social risk factors and reduces incentives to avoid these patients. More favorable allocation of resources to these providers would increase their resources (Damberg et al., 2015), which they could invest in reducing disparities and improving

quality and efficiency. However, if the payment formula is adjusted directly, providers could be rewarded despite poor performance or poor outcomes, which would reduce incentives to improve care. Because directly adjusting payments does not affect publicly reported measures, this method does not make disparities visible unless coupled with public reporting stratified by patient characteristics within reporting units. Relatedly, if payment is directly adjusted, but performance is still reported without adjustment, then there could be incentives to avoid patients with social risk factors.

Restructured payment incentive designs do not explicitly incorporate measures of social risk factors; instead, they implicitly account for them. Like directly adjusting for payment, this implicit adjustment accounts for the increased resources needed to care for socially at-risk populations and therefore avoids unintentionally underpaying providers who serve these populations and reduces incentives to avoid patients with social risk factors. Payment incentives can be restructured in several ways. For example, in addition to other rewards and penalties, providers and plans could receive a bonus for having low disparities (Blustein et al., 2010; Casalino et al., 2007). This has the obvious advantages of directly incentivizing disparities reduction. Similarly, providers and plans could receive a bonus for improving quality and efficiency relative to their own benchmark (i.e., paying for improvement) (Casalino et al., 2007; Rosenthal et al., 2004). This would directly incentivize quality improvement and efficiency, but may also reward providers at lower levels of absolute performance. Like directly adjusting payments, restructuring payment incentive design does not affect publicly reported measures and therefore does not improve the accuracy of performance scores. Restructuring incentive design does not make disparities visible unless it is combined with public reporting stratified by patient characteristics within reporting units.

Comprehensive descriptions of the 10 methods, as well as their advantages and disadvantages can be found in Table C4-1 in Appendix C. Table 3-1 in Chapter 3 summarizes how different categories of methods to account for social risk factors might achieve the committee’s four policy goals. Table 3-2 summarizes how different categories of methods might result in unintended consequences. Chapter 3 includes an example of how these four methods could be applied to one of Medicare’s flagship programs, the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program.

Comments on Unintended Consequences

The committee expands on two potential unintended consequences about which some opponents of accounting for social risk factors have raised particular concerns and suggests how these unintended consequences might be mitigated. First, some opponents of accounting for social risk fac-

tors worry that by making it easier for providers and plans to reach performance targets or rewarding them at lower levels of absolute performance, accounting for social risk factors may remove incentives to improve quality and efficiency (in particular, to exceed benchmarks) for patients with social risk factors (Bernheim, 2014; Kertesz, 2014; Krumholz and Bernheim, 2014; O’Kane, 2015). The committee recognizes that certain methods may diminish (but not entirely remove) incentives to improve quality and reduce disparities, but the committee also suggests that any approach must be sure to include sufficient incentive for quality improvement for all patients, including socially at-risk populations. As described above and as the committee concluded, achieving this might require a combination of reporting and payment methods.6

Second, critics of adjustment are concerned that accounting for social risk factors would obscure differences that arise from poor quality care (Krumholz and Bernheim, 2014). A risk of some methods to account for social risk factors is the perception of different standards for different populations, which could have negative symbolic value. Approaches that adjust for and report by patient characteristics and within-provider differences are less subject to this concern than approaches that would adjust for and report by provider characteristics. The committee emphasizes if CMS’s goals for VBP include monitoring and reducing disparities, then because only public reporting stratified by patient characteristics within reporting units makes disparities visible by providing quality information for different subgroups, stratified public reporting by patient characteristics within reporting units must be part of any approach to improve on the status quo.

Conclusion: The committee supports four goals of accounting for social risk factors in Medicare payment programs: reducing disparities in access, quality and outcomes; improving quality and efficient care delivery for all patients; fair and accurate reporting; and compensating health plans and providers fairly. These goals would best be achieved through payment based on performance measure scores adjusted for social risk factors (or adjusting payment directly for these risk factors) when combined with public reporting stratified by patient characteristics within reporting units.

The committee notes that some restructuring of payment formulas may still be needed to ensure that there are sufficient incentives for health plans and providers to improve access, quality, and outcomes for groups that are disadvantaged by high levels of social risk factors. Payment formulas that

___________________

6 See Conclusion 6 in the committee’s third report (NASEM, 2016b).

incentivize improving care for disadvantaged individuals and communities may include paying for performance or change in performance for subgroups with high levels of social risk factors. Furthermore, improving health equity may require both accounting for social risk factors in payment and quality improvement interventions.

MOVING FORWARD

The committee recognizes that implementing any approach to accounting for social risk factors in Medicare quality measurement and payment can be complex and will require substantial analyses to identify the best approaches to do so for different Medicare incentive programs; it will also require considerable resources—including costs. This final report provides some clarifications, observations, and other considerations to guide ASPE and CMS if they choose to begin accounting for social risk factors in Medicare payment programs, and to help them to identify priorities and preferences from among the options presented.

Existing analyses do not address which of the social risk factors that may influence performance indicators used in VBP must be individually accounted for to ensure adjustments to performance measures and payment are accurate. It may be that some are not adequately measured using current data or data collection techniques. It may also be that a smaller set of indicators is sufficient. If the latter, the literature does not currently indicate which factors should be included. Thus, in order to determine which social risk factors should be incorporated in any given VBP system, their usefulness in explaining variation in outcomes should be investigated. ASPE has already conducted some analyses of the associations of different types of social risk factors with certain outcomes (Filice and Joynt, 2016; Samson et al., 2016; Snyder et al., 2016).

Research Suggestions

Further research could inform ASPE or CMS as they determine the optimal way in which to adjust indicators used in VBP for social risk factors. Specifically, further work would address the following questions:

- How can ASPE/CMS implement the use of an initial set of social risk factors on a rapid timeline?

- How can ASPE/CMS implement the use of an expanded set of social risk factors?

- How can ASPE/CMS monitor and refine the use of social risk factors in VBP?

Chapter 4 elaborates on these questions. Through research answering these questions ASPE/CMS can determine the best path for implementing adjustments for social risk factors, and can ensure that doing so furthers the policy goals of VBP.

Improving Care for All Socially At-Risk Populations

To the extent that accounting for social risk factors in Medicare payment improves fairness in compensating providers disproportionately serving socially at-risk populations, doing so may increase the resources available to these providers to invest in quality improvement and disparities reduction. The approaches the committee identified to account for social risk factors in quality measurement and payment could be applied to other payers, which could further increase resources to these providers via the same mechanisms as under Medicare. However, any policy that modifies incentive payments (as accounting for social risk factors in these payment does) does not (and cannot) fix the payment system at large, nor does it solve the problem of safety-net financing. Indeed, other payment reforms (for example, direct payments for quality improvement among safety-net providers and direct payments to incentivize collaboration with public health and social service agencies and community-based organizations) may also be needed to incentivize high-quality care for socially at-risk populations. Accounting for social risk factors is necessary but insufficient by itself to achieve health equity. Achieving equity may require accounting for social risk factors as well as other payment reforms, further research to identify what drives observed differences in quality and outcomes for patients with social risk factors, and interventions to improve the quality of care and to reduce disparities.

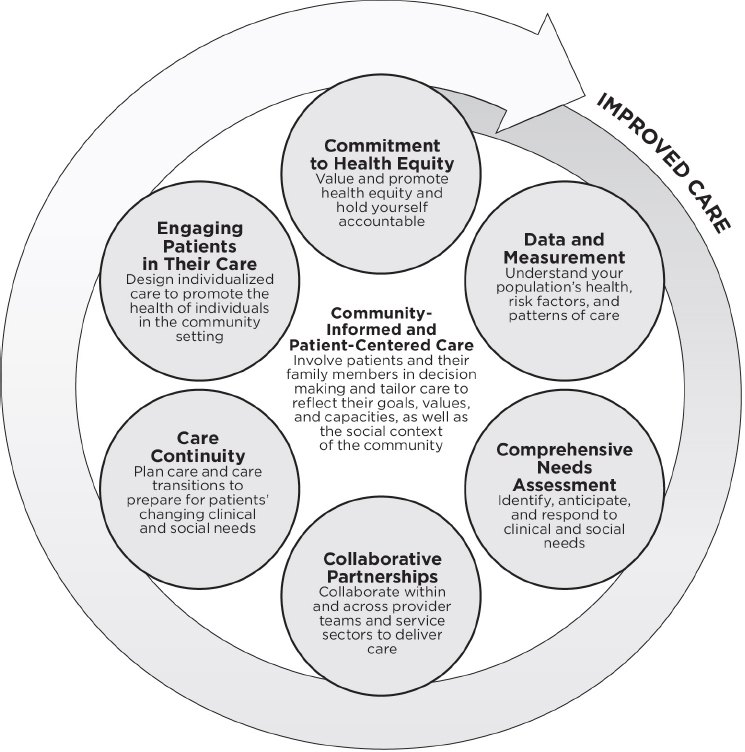

The committee’s second report, Systems Practices for the Care of Socially At-Risk Populations, shows that there are strategies health care providers and payers can undertake to improve care and health outcomes for socially at-risk populations (NASEM, 2016d). The committee identified commonalities across the strategies identified. These six systems practices, grounded in community-informed and patient-centered care, are shown in Figure S-2. In this approach, the health care system includes not only medical providers, but it also partners with public health and social service agencies, community-based organizations, and the community in which those medical providers are embedded. The committee found evidence that it is possible to deliver high-quality care to socially at-risk populations, and patients with social risk factors need not experience low-quality care and poor health outcomes.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The committee urges policy makers to remember that quality measurement and payment policies affect the lives of real patients. In the case of accounting for social risk factors, changes to the current VBP system would especially influence the lives of patients with social risk factors who have historically experienced barriers to accessing high quality health care. Together, accounting for social risk factors in quality measurement and payment in combination with complementary approaches may achieve the policy goals of reducing disparities in access, quality, and outcomes, as

well as quality improvement and efficient care delivery for all patients, and thereby promote health equity.

REFERENCES

Berkman, L., and T. Glass. 2000. Social integration, social networks, social support, and health. In Social epidemiology, edited by L. F. Berkman and I. Kawachi. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bernheim, S. M. 2014. Measuring quality and enacting policy: Readmission rates and socioeconomic factors. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes 7(3):350-352.

Blustein, J., W. B. Borden, and M. Valentine. 2010. Hospital performance, the local economy, and the local workforce: Findings from a US national longitudinal study. PLoS Medicine 7(6):e1000297.

Boozary, A. S., J. Manchin, 3rd, and R. F. Wicker. 2015. The Medicare Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program: Time for reform. Journal of the American Medical Association 314(4):347-348.

Braveman, P., and S. Gruskin. 2003. Defining equity in health. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 57(4):254-258.

Burwell, S. M. 2015. Setting value-based payment goals—HHS efforts to improve U.S. healthcare. New England Journal of Medicine 372(10):897-899.

Casalino, L. P., A. Elster, A. Eisenberg, E. Lewis, J. Montgomery, and D. Ramos. 2007. Will pay-for-performance and quality reporting affect health care disparities? Health Affairs (Millwood) 26(3):w405-w414.

Chien, A. T., M. H. Chin, A. M. Davis, and L. P. Casalino. 2007. Pay for performance, public reporting, and racial disparities in health care: How are programs being designed? Medical Care Research and Review 64(5 Suppl):283s-304s.

CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services). 2015. Medicare program; contract year 2016 policy and technical changes to the Medicare Advantage and the Medicare prescription drug benefit programs. Final Rule. Federal Register 80(29):7911.

Cohen, S. 2004. Social relationships and health. American Psychologist 59(8):676-684.

Damberg, C. L., M. N. Elliott, and B. A. Ewing. 2015. Pay-for-performance schemes that use patient and provider categories would reduce payment disparities. Health Affairs (Millwood) 34(1):134-142.

Eng, P. M., E. B. Rimm, G. Fitzmaurice, and I. Kawachi. 2002. Social ties and change in social ties in relation to subsequent total and cause-specific mortality and coronary heart disease incidence in men. American Journal of Epidemiology 155(8):700-709.

Feemster, L. C., and D. H. Au. 2014. Penalizing hospitals for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease readmissions. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 189(6):634-639.

Filice, C. E., and K. E. Joynt. 2016. Examining race and ethnicity information in Medicare administrative data. Medical Care. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000608 (accessed December 20, 2016).

Fiscella, K., H. R. Burstin, and D. R. Nerenz. 2014. Quality measures and sociodemographic risk factors: To adjust or not to adjust. Journal of the American Medical Association 312(24):2615-2616.

Girotti, M. E., T. Shih, S. Revels, and J. B. Dimick. 2014. Racial disparities in readmissions and site of care for major surgery. JAMA Surgery 218(3):423-430.

House, J. S., K. R. Landis, and D. Umberson. 1988. Social relationships and health. Science 241(4865):540-545.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2001. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2004. Health literacy: A prescription to end confusion. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2007a. Rewarding provider performance: Aligning incentives in Medicare (pathways to quality health care series). Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2007b. The future of disability in America. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2011. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2014. Capturing social and behavioral domains and measures in electronic health records: Phase 2. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Jha, A. K., and A. M. Zaslavsky. 2014. Quality reporting that addresses disparities in health care. Journal of the American Medical Association 312(3):225-226.

Joynt, K. E., and A. K. Jha. 2013. A path forward on Medicare readmissions. New England Journal of Medicine 368(13):1175-1177.

Kertesz, K. 2014. Center for Medicare advocacy comments on the impact of dual eligibility on MA and part D quality scores. http://www.medicareadvocacy.org/center-for-medicare-advocacy-comments-on-the-impact-of-dual-eligibility-on-ma-and-part-d-quality-scores (accessed December 20, 2016).

Krieger, N., D. R. Williams, and N. E. Moss. 1997. Measuring social class in US public health research: Concepts, methodologies, and guidelines. Annual Review of Public Health 18:341-378.

Krumholz, H. M., and S. M. Bernheim. 2014. Considering the role of socioeconomic status in hospital outcomes measures. Annals of Internal Medicine 161(11):833-834.

Lipstein, S. H., and W. C. Dunagan. 2014. The risks of not adjusting performance measures for sociodemographic factors. Annals of Internal Medicine 161(8):594-596.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2016a. Accounting for social risk factors in Medicare payment: Identifying social risk factors. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2016b. Accounting for social risk factors in Medicare payment: Criteria, factors, and methods. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2016c. Accounting for social risk factors in Medicare payment: Data. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2016d. Systems practices for the care of socially at-risk populations. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

O’Kane, M. 2015. Comment on the advance notice of methodological changes for calender year 2016 for Medicare Advantage call letter. http://www.ncqa.org/public-policy/comment-letters/medicare-advantage-03-2015 (accessed December 20, 2016).

Pollack, R. 2013. CMS-1599-p, Medicare program; hospital Inpatient Prospective Payment Systems for acute care hospitals and the long-term care hospital Prospective Payment System and proposed fiscal year 2014 rates; quality reporting requirements for specific providers; hospital conditions of participation; Medicare program; Proposed Rule (vol. 78, no. 91): Letter to the CMS Administrator Tavenner. http://www.aha.org/advocacy-issues/letter/2013/130620-cl-cms-1599p.pdf (accessed December 20, 2016).

Renacci, J. B. 2014. Letter to HHS Secretary Burwell and CMS Administrator Tavenner regarding the Medicare Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. http://tinyurl.com/q6shyoc (accessed October 30, 2015).

ResDAC (Research Data Assistance Center). n.d. Health and Retirement Survey—Medicare linked data. https://www.resdac.org/cms-data/files/hrs-medicare (accessed August 4, 2016).

Rosenthal, M. B. 2008. Beyond pay for performance—emerging models of provider-payment reform. New England Journal of Medicine 359(12):1197-1200.

Rosenthal, M. B., R. Fernandopulle, H. R. Song, and B. Landon. 2004. Paying for quality: Providers’ incentives for quality improvement. Health Affairs (Millwood) 23(2):127-141.

Ryan, A. M. 2013. Will value-based purchasing increase disparities in care? New England Journal of Medicine 369(26):2472-2474.

Samson, L. W., K. Finegold, A. Ahmed, M. Jensen, C. E. Filice, and K. E. Joynt. 2016. Examining measures of income and poverty in Medicare administrative data. Medical Care. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000606 (accessed December 20, 2016).

Snyder, J. E., M. Jensen, N. X. Nguyen, C. E. Filice, and K. E. Joynt. 2016. Defining rurality in Medicare administrative data. Medical Care. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000607 (accessed December 20, 2016).

WHO (World Health Organization). 2001. International classification of functioning, disability and health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

Williams, D. R. 1997. Race and health: Basic questions, emerging directions. Annals of Epidemiology 7(5):322-333.