CS

Summary

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) are steadily moving from paying for volume (fee-for-service payments) to paying for quality, outcomes, and costs (value-based payment [VBP]) in the traditional Medicare program. Since Congress enacted the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, CMS has implemented a variety of VBP models, including quality incentives and risk-based, alternative payment models (APMs) (Burwell, 2015). In this report both types of strategies are referred to broadly as VBP. Financial incentives such as pay-for-performance programs link financial bonuses and/or penalties to quality or value (NASEM, 2016a). APMs include episode-based payments and population-based (global) payments, shifting greater financial risk to providers to hold them accountable for the quality and efficiency of care they provide, as well as health outcomes achieved (NASEM, 2016a). Although not considered entirely VBP models, Medicare Part C (i.e., Medicare Advantage) and Part D also have design features that tie quality and cost performance to payment (e.g., risk sharing and bonus payments).

Stakeholders have raised concerns that current Medicare quality measurement and payment programs, and VBP programs in particular, that do not account for social risk factors may underestimate the quality of care provided by providers disproportionately serving socially at-risk populations.1 Patients with social risk factors may require more resources and more intensive care to achieve certain health outcomes compared to the

___________________

1 Note, the term provider in this report refers to the reporting unit (or, provider setting) being evaluated—e.g., hospitals, health plans, provider groups, etc.

resources and care needed to achieve those same outcomes in more advantaged patients (NASEM, 2016b). At the same time, because these providers are also more likely to care for patients who are uninsured or covered by Medicaid, they have historically been less well funded than providers caring for larger proportions of patients with commercial insurance that pay more generously for care. If providers disproportionately serving vulnerable populations are likely to have fewer resources to begin with and care for patients who require more resources to achieve the same health care outcomes, these providers may be more likely to fare poorly on quality rankings (Chien et al., 2007; Joynt and Rosenthal, 2012; Ryan, 2013). The poorer average performance among providers disproportionately serving socially at-risk populations combined with the fact that they have fewer resources has raised concerns that Medicare’s VBP programs may potentially increase disparities. Similar concerns apply to capitated payments made to Medicare Part C health plans.

STATEMENT OF TASK

In response to concerns about health equity and accuracy in reporting and to the Improving Medicare Post-Acute Care Transformation (IMPACT) Act approved by Congress in 2014, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) acting through the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) contracted with the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to convene an ad hoc committee to identify criteria for selecting social risk factors, specific social risk factors Medicare could use, and methods of accounting for those factors in Medicare quality measurement and payment applications. The committee comprises expertise in health care quality, clinical medicine, health services research, health disparities, social determinants of health, risk adjustment, and Medicare programs (see Appendix B for biographical sketches).

This report is the third in a series of five brief reports that aim to inform ASPE analyses that account for social risk factors in Medicare payment programs mandated through the IMPACT Act. In the first report, the committee presented a conceptual framework and described the results of a literature search linking five social risk factors and health literacy to health-related measures of importance to Medicare quality measurement and payment programs—referred to in this report as performance indicators used in VBP. In the second report, the committee reviewed the performance of providers disproportionately serving socially at-risk populations, discussed drivers of variations in performance, and identified six community-informed and patient-centered systems practices that show promise to improve care for socially at-risk populations. Details of the statement of task and the sequence of reports can be found in Box C1-1. The committee will release reports every

3 months, addressing each item in the statement of task in turn. The statement of task requests committee recommendations only in the fourth report.

This report builds on the conceptual relationships and empirical associations between social risk factors and performance indicators used in VBP identified in the first report to provide guidance on which factors could be considered for Medicare accounting purposes, criteria to identify these factors, and methods to do so in ways that can improve care and promote greater health equity for socially at-risk patients. To that end, the committee also aims to address issues that must be carefully considered to maintain or enhance provider incentives to improve care for socially at-risk patients throughout the report while also promoting accuracy in reporting and compensating providers fairly. The committee’s goals in accounting for social risk factors in Medicare payment programs are

- Reducing disparities in access, quality, and outcomes;

- Quality improvement and efficient care delivery for all patients;

- Fair and accurate public reporting; and

- Compensating providers fairly.

To achieve these goals, accounting for social risk factors should neither mask low-quality care or health disparities nor reward poor performance. Additionally, inclusion of social risk factors in quality measurement and payment should not disincentivize providers from finding strategies to overcome the influence of social risk factors on health care outcomes.

CRITERIA FOR SELECTING SOCIAL RISK FACTORS

The primary goal of the criteria is to guide selection of social risk factors that could be accounted for in VBP so that providers or health plans are rewarded for delivering quality and value independent of whether they serve patients with relatively low or high levels of social risk factors. Under VBP, providers who care for patients who would score lower on the measures of performance as a result of factors outside of the providers’ control (such as certain social risk factors), rather than as a result of the quality of care delivered, should not be penalized because of the influence of these non-modifiable factors. The effect of these other factors should be minimized. In sum, the criteria should guide identification of social risk factors that could be accounted for in performance indicators used in VBP to promote accuracy in reporting.

The criteria put forth by this committee adhere closely to the guidelines for selecting risk factors developed by the National Quality Forum (NQF) in their 2014 report Risk Adjustment for Socioeconomic Status or Other Sociodemographic Factors. Like NQF, the committee’s criteria explicitly

focuses on selecting risk factors that will be applied to adjustment of performance indicators used for VBP. However, the committee’s criteria reflect the need to apply to a broader range of methods to account for social risk factors. Criteria developed to select risk factors for prior risk adjustment models that the committee reviewed and drew upon in developing their criteria are listed in Appendix CA.

Conclusion 1: Three overarching considerations encompassing five criteria could be used to determine whether a social risk factor should be accounted for in performance indicators used in Medicare value-based payment programs. They are as follows:

-

The social risk factor is related to the outcome.

- The social risk factor has a conceptual relationship with the outcome of interest.

- The social risk factor has an empirical association with the outcome of interest.

-

The social risk factor precedes care delivery and is not a consequence of the quality of care.

- The social risk factor is present at the start of care.

- The social risk factor is not modifiable through provider actions.

-

The social risk factor is not something the provider can manipulate.

- The social risk factor is resistant to manipulation or gaming.

These criteria are described and summarized in Table CS-1, along with the rationale and limitations of each criterion, as well as practical considerations.

APPLYING CRITERIA TO SOCIAL RISK FACTORS AND HEALTH LITERACY

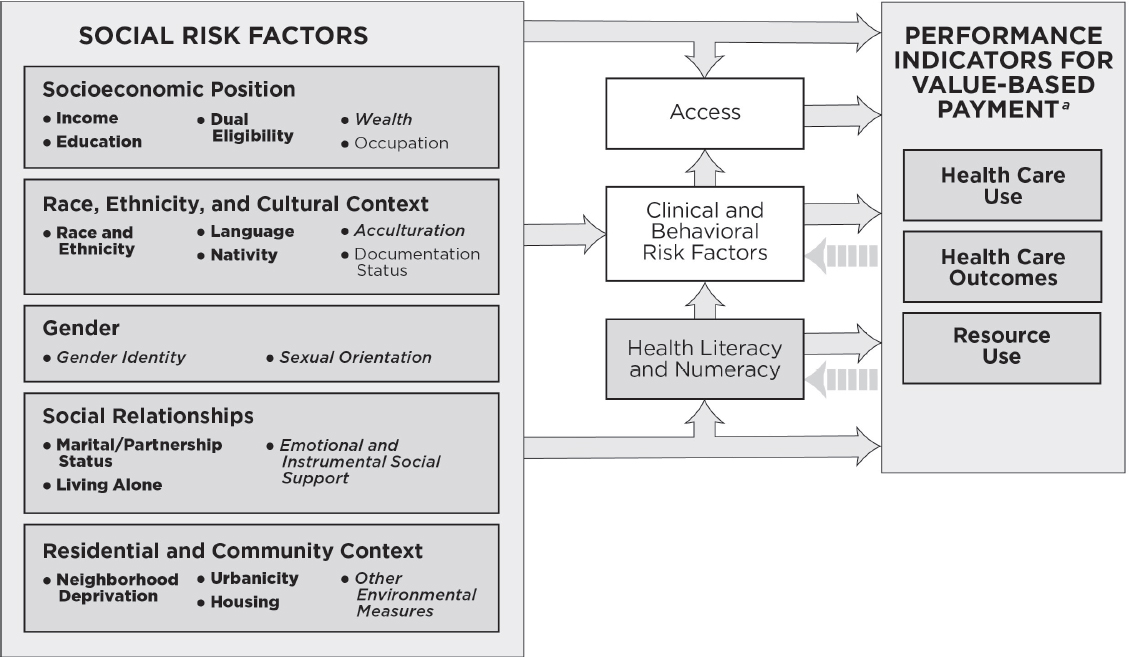

The conceptual framework presented in the committee’s first report (see Appendix A) illustrates the primary hypothesized conceptual pathways by which five social risk factors (socioeconomic position [SEP]; race, ethnicity, and cultural context; gender; social relationships; and residential and community context) as well as health literacy may directly or indirectly affect performance indicators used in Medicare VBP programs (NASEM, 2016a). As described in the committee’s first report, the conceptual framework applies to all Medicare beneficiaries, including beneficiaries with disabilities and those with end-stage renal disease. The committee also identified specific indicators that correspond to the social risk factors. These indicators represent ways to measure the latent constructs of the social risk factors and are distinct from specific measures.

Figure CS-1 illustrates the primary hypothesized relationships between social risk factors and health literacy and performance indicators used in VBP. The committee applied the selection criteria they developed to the five social risk factors (and their respective indicators) and health literacy, and also describes the rationale and limitations of each factor and indicator relative to those criteria.

Socioeconomic Position

SEP is commonly measured using indicators including income and wealth, education, and occupation and employment. In the medical field, insurance status is also used as a proxy for SEP. Income and education are promising indicators of SEP, because they are related to health care outcomes of interest, precede care delivery and are not a consequence of the quality of care, and meet practical considerations; measures are likely to be resistant to gaming and manipulation. Wealth is likely to be strongly associated with health and health care outcomes, but accurate data is difficult to collect. Dual eligibility as a proxy for SEP is also an available measure that meets practical criteria. Because dual eligibility captures elements of income, wealth, and health status, dual eligibility can be considered a broader measure of health-related resource availability that captures medical need. Occupation is likely to be strongly associated with performance indicators used in VBP, but practical considerations limit its potential use.

Race, Ethnicity, and Cultural Context

Indicators in this category include race, ethnicity, language, nativity, immigration history, and acculturation. Race, ethnicity, language (especially limited English proficiency), and nativity (i.e., foreign-born versus U.S. born; country of origin) are promising indicators, particularly in combination. Literature supports a conceptual relationship between acculturation and health care outcomes of interest, but existing measures have limitations, and empirical evidence is lacking. Documentation status as a measure of immigration history is likely to be sensitive to collect.

Gender

Normative gender categories (men and women) are strong candidates for inclusion in accounting methods, despite the fact that effects of gender are difficult to separate from biological effects of sex empirically. However, the committee notes that gender is already included in clinical risk adjustment. The relationship between gender identity (describing individuals who identify as transgender, intersex, or otherwise nonconforming gender)

TABLE CS-1 Criteria for Selecting Social Risk Factors for Application in Medicare Quality Measurement and Payment, Rationale, and Potential Challenges

| Criteria | Rationale | Challenges/Limitations | Practical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. The social risk factor is related to the outcome. This category is the most basic pair of criteria for a social risk factor—that there be both a plausible and valid reason why the risk factor would be associated with the outcome and empirical evidence that such a relationship holds in practice. Together these criteria lay the foundation for the validity and practical importance of the risk factor. |

|||

| 1. Conceptual relationship with the outcome of interest | A conceptual relationship informed by research and experience ensures that there is a reasonable conceptual basis for expecting a systematic relationship. | A conceptual relationship may not be consistent over time or across settings. It is not always possible to distinguish unique causal roles of factors so usefulness in an adjustment model does not necessarily imply that outcomes would improve through interventions on risk factor. | Acceptability and face validity: Some factors may be indicated empirically, but would need to be excluded because it has poor face validity or because data would be unacceptable to collect and include. |

| 2. Empirical association with the outcome of interest | An empirical association confirms the conceptual relationship. Without this criterion, an adjustor (social risk factor) may have no effect. | Empirical evidence may not be generalizable to the particular setting. Relationship may not hold in multivariate model. | Data limitations often represent a practical constraint to what factors are included in risk models. The aim is to reliably and feasibly capture accurate data. The challenge is to push for greater reliability and feasibility of factors that may be important to include, even if factors are excluded today, because it is currently infeasible. Privacy laws and concerns about patient confidentiality may also be an issue. Contribution of unique variation in the outcome (i.e., not redundant or highly correlated with another risk factor): Prevent overfitting and unstable estimates, or coefficients that appear to be in the wrong direction; reduce data collection burden. |

| B. Social risk factor precedes care delivery and is not a consequence of the quality of care. Factors that reflect a model of care delivery, a treatment decision, or the direct consequences of care or treatment decision are not appropriate adjustors, as they reflect true differences in quality of care or other outcomes. |

|||

| 3. The risk factor is present at the start of care. | If a risk factor is present at start of care, then it is less likely that it would be the result of care provided. | Does not eliminate a risk factor being a consequence of care delivery in dynamic settings or under population health settings. | Prioritize slowly changing factors over rapidly changing variables: Measurement would have to be more frequent, but rapidly changing variables would not fully disqualify a measure. Consider whether a factor represents a cumulative life cycle effect or a transient effect. |

| 4. The risk factor is not modifiable through the provider actions. | The goal is to adjust for factors independent of the care provided. Adjusting for the care provided contravenes this goal. | It may be difficult to identify in practice the extent to which care provision might affect a particular social risk factor. | |

| C. The social risk factor is not something that the provider can manipulate. | |||

| 5. The risk factor is resistant to manipulation or gaming. | This criterion ensures validity of performance score as representing quality of care (versus, for example, upcoding). | It is often difficult to anticipate how a measure might be manipulated. | Prioritize specific coding over vague coding: vague codes are more vulnerable to manipulation; however, there are vaguely coded variables that may be important nevertheless, so this would not fully disqualify an indicator. Prioritize continuous over dichotomous measures of the same constrict where applicable to reduce “edge” gaming. Carefully monitor high-leverage factors (i.e., risk factors that are not prevalent but highly predictive of outcomes), as they may be important but especially attractive for gaming. |

NOTES: This conceptual framework illustrates primary hypothesized conceptual relationships. For the indicators listed in bullets under each social risk factor, bold lettering denotes measurable indicators that could be accounted for in Medicare VBP programs in the short-term, italicized lettering denotes measurable indicators that capture the basic underlying constructs and currently present practical challenges, but are worth attention for potential inclusion in accounting methods in Medicare VBP programs in the longer term; and plain lettering denotes indicators that have considerable limitations.

a As described in the conceptual framework outlining primary hypothesized conceptual relationships between social risk factors and outcomes used in VBP presented in the committee’s first report (NASEM, 2016a), health care use captures measures of utilization and clinical processes of care; health care outcomes capture measures of patient safety, patient experience, and health outcomes; and resource use captures cost measures.

and sexual orientation (describing individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, questioning, or otherwise nonconforming) and health care outcomes is not well established. HHS is currently testing and collecting data on promising measures of gender identity and sexual orientation that could be revisited for potential inclusion when there is more evidence of an effect. In the short term, there is likely to be very low prevalence of individuals who have nonnormative gender identities. Thus, accounting for variations in gender identity is unlikely to have a significant effect in accounting methods.

Social Relationships

Social relationships are typically assessed using three indicators in health research: marital/partnership status, living alone, and emotional and instrumental social support. Marital/partnership status and living alone are likely to influence health and health care outcomes, are easy to measure, and may at least partly capture elements of emotional and instrumental social support. Some evidence suggests that the relationship between marital/partnership status and health is changing along with demographic shifts, which point to a need to reassess the empirical associations and revisit assumptions about the conceptual relationship over time. Emotional social support and instrumental social support are likely to influence health care outcomes. However, because social support is multidimensional, identifying the measure that represents the most relevant dimension for a given health care outcome may pose both conceptual and practical challenges for data collection and measurement.

Residential and Community Context

Residential and community context includes compositional characteristics that represent aggregate characteristics of neighborhood residents and characteristics of physical and social environments (i.e., environmental measures) (NASEM, 2016a). Compositional characteristics and environmental measures of residential and community context are related to health care outcomes, precede care delivery and are not a consequence of the quality of care, are not modifiable through provider action, and generally meet practical considerations, with some limitations. A measure of census tract-level neighborhood deprivation (i.e., a composite measure of neighborhood compositional characteristics) is likely a good proxy for a range of individual and true area-level constructs (compositional and environmental) relevant to performance indicators used in VBP. Measures of urbanicity and housing are also available. These measures are also feasible to obtain. Environmental measures are an emerging area of research and other mea-

sures could be revisited for potential inclusion when there is more empirical evidence and better measures.2

Health Literacy

The committee does not conceive of health literacy as a social risk factor, but rather as the product of an individual’s skills and abilities (e.g., reading and other critical skills), social and cultural factors, education, health system demands, and the health care context. However, the committee included health literacy in its conceptual framework and retained it for consideration in this report because health literacy is included in the committee’s charge and because it is specifically mentioned in the IMPACT Act and therefore of interest to Congress. Additionally, social risk factors like education and language influence health literacy. Health literacy (capturing the related construct of numeracy) is related to health care outcomes of interest and generally meets practical considerations. However, provider actions can potentially mitigate the effects of low health literacy. Thus, to preserve incentives to provide effective care to patients with low health literacy, it may be not be desirable to adjust performance measures to account for differences in health literacy. Nevertheless, it may be desirable to otherwise compensate providers for the greater effort or costs required to provide health literate care and thereby produce good health care outcomes.

After applying the selection criteria to indicators of the five social risk factors and health literacy, the committee made the following conclusions:

___________________

2 The committee sees no conflict between this report and the 2013 IOM report Variation in Health Care Spending: Target Decision Making, Not Geography, which recommended against using area-level payment adjustments to account for regional practice patterns. That committee’s charge was to evaluate whether area-level differences in per-beneficiary spending were real and if so, to develop explanations for the variation. That report examined whether health care markets (characterized using relatively large geographies such as hospital service areas, hospital referral regions, or metropolitan statistical areas) were characterized by persistent patterns of spending driven by commonalities in medical decision making or other provider behavior and concluded that area spending variability was mainly due to price markups in the commercial insurance market and variation in the use of post-acute care in Medicare. In contrast, this report focuses on differences in performance indicators used in VBP (including variations in health care utilization and resource use, but also quality) driven by differences in social characteristics of a provider or other risk-bearing entity’s patient population. The use of area-level measures is therefore at much smaller geographic units (e.g., census tracts of patient place of residence) and serves to more accurately characterize providers’ patient populations in Medicare quality measurement and payment programs.

Conclusion 2: There are measurable social risk factors that could be accounted for in Medicare value-based payment programs in the short term. Indicators include

- Income, education, and dual eligibility;

- Race, ethnicity, language, and nativity;

- Marital/partnership status and living alone; and

- Neighborhood deprivation, urbanicity, and housing.

Conclusion 3: There are some indicators of social risk factors that capture the basic underlying constructs and currently present practical challenges, but they are worth attention for potential inclusion in accounting methods in Medicare value-based payment programs in the longer term. These include

- Wealth,

- Acculturation,

- Gender identity and sexual orientation,

- Emotional and instrumental social support, and

- Environmental measures of residential and community context.

METHODS TO ACCOUNT FOR SOCIAL RISK FACTORS IN VALUE-BASED PAYMENT PROGRAMS

When developing and selecting methods to account for social risk factors in VBP programs, understanding the type of incentive design is important for evaluating the potential benefits and challenges of various accounting methods. The incentive design will interact with the method used to account for social risk factor(s) and produce certain potential benefits and risks. Selecting the appropriate method (or, methods) to account for social risk factors will depend on the balance of these potential positive and negative consequences.

CMS payment models cover a spectrum of approaches from traditional fee-for-service to population-based payment models. Current Medicare financial incentive programs include

- Hospital-Acquired Condition Payment Reduction,

- Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program,

- Hospital Value-Based Purchasing, and

- Physician Value-Based Modifier.

Current Medicare APMs include

- End-Stage Renal Disease Quality Incentive Program, and

- Medicare Shared Savings Program.

Other VBP mechanisms in Medicare payment programs include

- Medicare Advantage/Part C Star Ratings Bonus Payment and risk-adjusted capitation and

- Medicare Part D risk-adjusted capitation, individual reinsurance, and risk corridor adjustments.

VBP programs in development include

- Home Health Value-Based Purchasing,

- Skilled Nurse Facility Value-Based Purchasing, and

- Medicare and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA).

The Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation also tests innovative payment models. In early 2016, CMS identified 10 APMs, including several innovative models for inclusion under MACRA (CMS, 2016), such as (among others)

- Bundled Payment Care Improvement initiative,

- Next Generation Accountable Care Organizations, and

- Comprehensive Primary Care Plus.

Given that the Medicare VBP landscape is evolving and CMS is moving toward more comprehensive population-based APMs, the committee identified methods that could apply to any VBP program, not just the existing ones.

Potential Harms of the Status Quo Compared to Accounting for Social Risk Factors

Although adjustment for social risk factors could have important benefits, any proposal to account for social risk factors in Medicare payment programs will entail its own advantages and disadvantages that need to be carefully considered. The status quo (which does not account for social risk factors) has disadvantages that include incentives for providers and insurers to avoid serving patients with social risk factors, underpayment to providers who disproportionately serve socially at-risk populations, and underinvestment in quality of care. While proposals that do account for social risk factors would likely diminish these harms, there are also some potential ways in which accounting for social risk factors could incrementally introduce new harms. These include reducing incentives to improve care for patients with social risk factors and limiting the ability of socially at-risk patients to identify providers who will deliver the best care for

them. Neither an unadjusted or adjusted summary score provides information about which provider is better for a patient based on his or her level of social risk factors unless all providers are equally good or bad with all patients. Only stratification by social risk factors will reveal such insights. Additionally, any method that obscures differences due to poor quality could be unfair in terms of compensating providers who provide high-quality care. Finally, any method for accounting for social risk factors that holds providers to different standards for socially at-risk populations may create the perception that patients with social risk factors are entitled to a lower quality of care. Even if these concerns are unfounded, perceptions of inequitable treatment can further erode trust in the health care system among patients with social risk factors.

Conclusion 4: It is possible to improve on the status quo with regard to the effect of value-based payment on patients with social risk factors. However, it is also important to minimize potential harms to these patients and to monitor the effect of any specific approach to accounting for social risk factors to ensure the absence of any unanticipated adverse effects on health disparities.

Methods to Account for Social Risk Factors

The committee’s review of methods to account for social risk factors in Medicare VBP programs takes as the point of departure that the goals of Medicare payment and reporting systems are reducing disparities in health care access, affordability, quality, and outcomes; quality improvement and efficient care delivery for all patients; fair and accurate public reporting; and compensating providers fairly for the services they provide. Differences in quality by populations with social risk factors may reflect a combination of drivers, including mechanisms that occur during the patient–provider encounter (e.g., discrimination, bias), provider characteristics (e.g., fewer financial resources, fewer and lower-quality clinical/health care resources), and barriers to access and financial constraints for socially at-risk persons (NASEM, 2016b). In practice these mechanisms may occur simultaneously and also interact; it is difficult if not impossible to decompose observed differences into these components quantitatively. The committee therefore proposes approaches that do not require disentangling the mechanisms of these multiple pathways for social risk factors. The fact that some providers do well with socially at-risk populations does not imply that it is equally easy to do so on average, and such population differences may also affect the relationship between provider quality and observed provider scores. The standard for taking such factors into account should not be that it is impossible to provide optimal care, but that it is more difficult on average.

Taking such factors into account need not “adjust away” disparities. Lower levels of performance for any group should not be reported as sufficient or receive maximum rewards. However, a provider that does not achieve performance on par with top performers (i.e., optimal care) could still be eligible for some reward because, for example, it improved substantially relative to its own benchmark.

Conclusion 5: Characteristics of a public reporting and payment system that could accomplish the goals of reducing disparities in access, quality, and outcomes; quality improvement and efficient care delivery for all patients; fair and accurate public reporting; and compensating providers fairly include

- Transparency and accountability for overall performance and performance with respect to socially at-risk members of the population;

- Accurate performance measurement—with high reliability and without bias (systematic error) related to differences in populations served;

- Incentives for improvement overall and for socially at-risk groups, both within reporting units (i.e., the provider setting that is being evaluated—hospitals, health plans, etc.) and between reporting units.

The committee reviewed literature on a range of methods to account for risk factors in public reporting and payment systems for which inclusion of social risk factors may be appropriate, with the aim to be inclusive.

- Finding: The committee identified four categories—(A) public reporting; (B) adjustment of performance measure scores; (C) direct adjustment of payments; and (D) restructuring payment incentive design—encompassing 10 methods to account for social risk factors that could be used to address policy goals of reducing disparities in access, quality, and outcomes; quality improvement and efficient care delivery for all patients; fair and accurate public reporting; and compensating providers fairly.

Public reporting seeks to make overall quality visible—to consumers, providers, payers, and regulators (IOM, 2006). It may lead to quality improvement via reputation incentives, and particularly when linked to behavioral nudges, by increasing market share (i.e., influencing choice of provider) for higher-quality reporting units (IOM, 2006). Public reporting methods that could account for social risk factors include (1) stratification by patient characteristics within reporting units, and (2) stratification by reporting unit characteristics (e.g., comparing safety-net hospitals to peers).

Adjusting performance measure scores seeks to “level the playing field,” to estimate true reporting unit quality—that which would occur if all units had the population average patient. Social risk factors can be considered confounders of true performance if they are beyond provider control and unevenly distributed across units and thereby distort (bias) comparisons. Adjustment is a means to account for social risk factors statistically in an effort to more accurately measure true performance. Methods to adjust performance measure scores include (1) risk adjustment for mean within-provider differences, (2) risk adjustment for within- and between-provider differences, and (3) adding quality measures for performance for at-risk groups in addition to the overall measure.

VBPs incorporate explicit or implicit (as in the case of bundled or global payment including shared savings) rewards or penalties based on performance on quality and/or cost of care. This can be achieved through three underlying conceptual approaches. First, payers could pay more to those that are doing a better job in the measurement period (i.e., pay for achievement). Second, payers could pay for the mix of patients the reporting unit treats, that is, pay more to those that treat greater numbers of socially at-risk patients under the assumption that they simply need more resources. This approach lacks incentives to improve unless some other system for accountability is superimposed. Third, payers could pay for improvement, that is, pay more to those who improve to a greater degree.

The committee also expands on how VBP could incorporate measures of social risk factors. Payments could be directly adjusted using social risk factors, or incentive design could be restructured. Direct adjustments of payment explicitly use measures of social risk factors, but by themselves do not affect performance measure scores. Methods include (1) risk adjustment in payment formula without adjusting measured performance, and (2) stratification of benchmarks used for payment. Restructuring payment incentive designs do not explicitly use measures of social risk factors, but implicitly account for social risk factors. Methods include (1) paying for improvement relative to a reporting unit’s own benchmark (to a greater extent or exclusively), including “growth models”; (2) downweighting social risk factor-sensitive measures in payment; and (3) adding a bonus for low disparities.

Applying Methods to Account for Social Risk Factors

In many cases, methods from multiple categories can be used together. In some cases, multiple methods from a single category can be used in combination. In this respect, each approach has some advantages and disadvantages and a combination of approaches may yield a better result than any one method alone. The committee underscores that the benefits

and harms of any single or composite method of accounting for social risk factors should be assessed in reference to the status quo or some other feasible alternative rather than a perfect world in which social risk factors do not confound efforts to improve the quality and efficiency of health care delivery (referred to by some as a “full information” scenario).

Conclusion 6: To achieve goals of reducing disparities in access, quality, and outcomes; quality improvement and efficient care delivery for all patients; fair and accurate public reporting; and compensating providers fairly, a combination of reporting and accounting in both measures and payment are needed.

Considerations around the trade-offs of various methods of accounting for social risk factors are different for cost-related performance compared to quality performance. Costs in the context of VBP can refer to the costs of improving quality or achieving good outcomes for socially at-risk patient or to the cost of care billed to a payer. As noted earlier, because achieving high performance on performance indicators used in VBP may require greater investments on the part of health care providers and health plans to overcome barriers socially at-risk populations face, costs to achieve good outcomes and improve care quality for socially at-risk populations are likely to be higher than costs to achieve the same outcomes and improve care quality for more advantaged patients. Because at least some of these costs will be outside of the services that can be billed to payers like CMS, as described in an earlier section, a potential harm of not accounting for social risk factors in a VBP environment is that this increased cost may be a disincentive to care for socially at-risk populations. On the other hand, lower resource use observed in billed costs of care may reflect unmet need or barriers to access rather than the absence of waste. Thus, lower cost is not always better; whereas, higher quality is always better.

Conclusion 7: Strategies to account for social risk factors for measures of cost and efficiency may differ from strategies for quality measurement, because observed lower resource use may reflect unmet need rather than the absence of waste, and thus lower cost is not always better, while higher quality is always better.

Monitoring

Both the status quo and any new approach to accounting for social risk factors will have uncertain tradeoffs in terms of the goals of reducing disparities in access, quality, and outcomes; quality improvement and efficient care delivery for all patients; fair and accurate public reporting; and com-

pensating providers fairly. Many unknowable factors including provider and patient beliefs and behavioral responses will affect the results that any new system yields. Monitoring data on a variety of indicators will facilitate assessment of the effects of existing and new programs on potential unintended adverse effects—such as enrollment (for health plans), patient complaints, access to and quality of care for socially at-risk populations, and the financial sustainability of providers disproportionately caring for socially at-risk populations.

Conclusion 8: Any specific approach to accounting for social risk factors in Medicare quality and payment programs requires continuous monitoring with respect to the goals of reducing disparities in access, quality, and outcomes; quality improvement and efficient care delivery for all patients; fair and accurate public reporting; and compensating providers fairly.

Finally, because behavioral and other responses to new systems may change the balance of risks and benefits over time, to take into account these behavioral and other responses, the specific approach to accounting for social risk factors may need to be reassessed.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The committee notes that it is not within its statement of task to recommend whether social risk factors should be accounted for in VPB or how; that decision sits elsewhere. The committee hopes that the conclusions in this report help CMS and the Secretary of HHS make that important decision. In the next report, the committee tackles the question of how to gather the data that could be used to account for social risk factors in Medicare VBP.

REFERENCES

Burwell, S. M. 2015. Setting value-based payment goals—HHS efforts to improve U.S. health care. New England Journal of Medicine 372(10):897-899.

Chien, A. T., M. H. Chin, A. M. Davis, and L. P. Casalino. 2007. Pay for performance, public reporting, and racial disparities in health care: How are programs being designed? Medical Care Research and Review 64(5 Suppl):283s-304s.

CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services). 2016. Overview of select alternative payment models. https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2016-Fact-sheets-items/2016-03-03.html (accessed April 18, 2016).

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2006. Performance measurement: Accelerating improvement (pathways to quality health care series). Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2013. Variation in health care spending: Target decision making, not geography. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Joynt, K. E., and M. B. Rosenthal. 2012. Hospital value-based purchasing: Will Medicare’s new policy exacerbate disparities? Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes 5(2):148-149.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2016a. Accounting for social risk factors in Medicare payment: Identifying social risk factors. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2016b. Systems practices for the care of socially at-risk populations. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Ryan, A. M. 2013. Will value-based purchasing increase disparities in care? New England Journal of Medicine 369(26):2472-2474.