1

Introduction

Health equity means that every person has the opportunity to attain his or her full health potential, and socioeconomic position (SEP) or other socially determined circumstances do not hinder anyone from achieving this potential (CDC, 2015; NASEM, 2016a). As put forth in Crossing the Quality Chasm, the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM’s) seminal report on health care quality, equity is a critical aim of any high-performance health system (IOM, 2001). Health equity can be conceptualized at the level of a health care system or more broadly at the population level (IOM, 2001). Equitable health care represents a commitment by providers and payers to provide a universally high standard of health care quality to all patients and enrollees regardless of their individual characteristics (NASEM, 2016b). In other words, equitable health care refers to the availability, delivery, and quality of health care services based solely on individual needs and preferences, rather than on differences by individual characteristics such as race/ethnicity, SEP, and other social risk factors (IOM, 2001). Achieving this may require greater resources and more intensive care for patients with social risk factors compared to more advantaged patients. At the population level, health equity is an ethical value that promotes improvement in health status for all individuals (Braveman and Gruskin, 2003; IOM, 2001). Achieving health equity may require reducing the influence of unfair inequalities in health status by power, wealth, or prestige, which may exist across social groupings owing to social risk factors such as income, race and ethnicity, or gender (Braveman and Gruskin, 2003; IOM, 2001; NASEM, 2016b).

The social risk factors that contribute to health disparities often lie outside of the health care system and therefore may not be modifiable by

actors within the health system (including providers and payers). Thus, equity in health status and health outcomes (health equity at the population level) may not be attainable within a health care system (i.e., through the provision of equitable health care alone). In other words, because achieving the same health care outcomes, health status, or health improvements may require remediating deep social inequalities in social risk factors such as inadequate housing or food insecurity, providing equitable health care is unlikely to be sufficient on its own to achieve health equity at the population level (NASEM, 2016b,d). The committee recognizes there may be opportunities for targeted intervention on social risk factors outside of the health system, and while such interventions can provide meaningful benefits to patients, they are unlikely to achieve full population health equity. At the same time, providers can nevertheless address social risk factors to mitigate their effect on health care outcomes such as through tailored approaches to achieving good outcomes. Indeed, the committee found evidence that it is possible to achieve good outcomes for socially at-risk populations (NASEM, 2016d). However, when social risk factors are not accounted for in performance measurement and payment in the health care system, achieving performance benchmarks (i.e., good outcomes) may be more difficult for providers disproportionately serving socially at-risk populations owing to the influence of social risk factors.

One lever to achieve high-performance health systems, including one that promotes equity, is through payment. Payment policies in the health care system can influence health and health care outcomes by encouraging or discouraging provider behavior (such as how health care providers and health systems deliver care) and patient behavior (such as how patients select and use care) (IOM, 2001). When payment strategies are aligned with such policy goals as improving quality and efficiency in health care or reducing disparities, payment can help incentivize these goals. When payment strategies and policy goals are misaligned, payment can act as a barrier. The misalignment of traditional, fee-for-service payment and the goals of high-performing health systems—safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable care—has been documented extensively elsewhere (e.g., IOM, 2001).

Reforms to better align payment with policy goals shift from paying for volume (fee-for-service) to paying for quality, also known as value-based payment (VBP). Specifically, VBP programs aim to improve the quality of care and the efficiency of delivering care, while also controlling costs (Burwell, 2015; Rosenthal, 2008). VBP strategies to achieve these goals can be broadly classified in two categories, which the committee characterizes as financial or quality incentives and risk-based alternative payment models. Financial or quality incentives such as pay-for-performance tie financial bonuses or penalties to quality or value; whereas, risk-based alternative pay-

ment models such as bundled payments and accountable care organizations (ACOs) shift greater financial risk to health care providers to hold them accountable for the care they provide and the health outcomes they achieve.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and other health care payers have increasingly moved from traditional, fee-for-service payment models to VBP and are continuing to do so at a rapid rate (Burwell, 2015). In 2015, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Sylvia Burwell set goals for CMS to have 85 percent of fee-for-service Medicare payments tied to quality or value by 2016 and 90 percent by 2018, and to have 30 percent of Medicare payment in alternative payment models by 2016 and 50 percent by 2018 (Burwell, 2015). In March 2016, CMS announced that it achieved its goal to have 30 percent of Medicare payments made through alternative payment models (HHS, 2016).

Although the goals of VBP programs are explicitly to improve health care quality and outcomes and to control costs, the focus on health care outcomes provides implicit incentive to address social risk factors that may contribute to poor health care outcomes and to health disparities. This can be seen in ACOs, which explicitly aim to improve population health (Berwick, 2011a,b). ACO contracts provide financial incentives to improve health and health care and to control costs for patients that payers attribute to the ACO (their panel population). Importantly, this includes patients who have barriers accessing care. This responsibility incentivizes providers to proactively and systematically improve the health of their entire panel population, even beyond the clinical encounter, and particularly with respect to preventing and managing chronic illnesses (Casalino et al., 2007). Efforts to do say may include addressing social risk factors for poor health care outcomes. For example, in the prevention and management of patients with diabetes, clinicians might not only monitor clinical risks but also assess patients’ feasible opportunities for a healthy diet and physical activity and refer patients to community resources to support a healthy diet and promote physical activity (NASEM, 2016d).

A broader approach defines the population in population health more expansively than a health care provider or plan’s panel population. As described in the committee’s second report, Systems Practices for the Care of Socially At-Risk Populations (NASEM, 2016d), the committee endorses a definition of population health where the population “refers to all people residing in the provider’s catchment area or the geographic community it serves, and is not restricted to an enrollee or patient population” (NASEM, 2016d, p. 38). Such an interpretation therefore extends beyond current patients to also include all members of the community a hospital or health plan serves. This approach to population health might also consider the distribution of health outcomes within the defined population group and therefore the multiple determinants of these health outcomes (Kindig and

Stoddart, 2003). These determinants include health care, but they also include social risk factors that lie outside of the medical system (Kindig and Stoddart, 2003). Thus, health care organizations that have adopted this broader approach to improving population health not only actively manage the health of their panel population, but they have also begun to intervene on social risk factors “beyond their walls.” As described in the committee’s second report, some providers are collaborating with social service and public health agencies and community-based organizations to link clinical interventions to social programs such as housing assistance, vocational counseling, legal assistance, and assistance applying for government benefits (NASEM, 2016d). Other providers are directly intervening on social risk factors, such as through the provision of transportation assistance, career and education counseling, and life skills and financial literacy training; hosting farmers markets to increase access to healthy foods; and even integrating clinical care and supportive housing (NASEM, 2016d). In recognition of these increasing efforts by health care organizations to intervene on social risk factors, CMS launched the Accountable Health Communities model under the auspices of the CMS Innovation Center. This model aims to test whether systematically screening for and addressing unmet social needs can reduce health care use and costs (Alley et al., 2016). The model is founded on screening, but also links payment to three tiers of approaches to addressing social risk factors: awareness, assistance, and alignment (Alley et al., 2016; Minyard, 2016).

Another policy that encourages providers to address social risk factors is the community benefit requirement for nonprofit hospitals to maintain their tax exempt status under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA). For historical reasons, community benefit is often used synonymously with charity care, or subsidizing health care costs for patients who cannot afford them. However, the ACA’s community benefit requirement as finalized by the Internal Revenue Service in Section 501(r) in the Internal Revenue Code requires tax-exempt hospitals to not only establish a written financial assistance (charity care) policy, but also to conduct a community health needs assessment at least once every 3 years (IRS, 2016). Importantly, the Internal Revenue Code defines community and health needs broadly. Community refers to the community that needs the care of the hospital, not just existing patients, and health needs refer not only to health care needs, but also health needs that arise from social risk factors (Rosenbaum, 2015). Because the requirement to conduct a community health needs assessment includes not only the description of needs and available resources, but also a plan to address significant needs identified, it aims to inform community benefit spending. By defining community health broadly, the requirement clarifies that community benefit spending can include not only charity care, but also investments in com-

munity health improvement. Because the new requirements arose from concerns over whether nonprofit hospitals historically provide sufficient charity care to justify their tax-exempt status, it is logical that the vast majority of community benefits currently goes toward subsidizing health care costs (Nikpay and Ayanian, 2015; Young et al., 2013). Nevertheless, a small proportion of community benefits goes toward community health improvement activities, and some of these efforts include addressing social risk factors for poor health care outcomes, such as violence prevention programs, advocating for housing improvements, and promoting literacy (Casalino et al., 2015; Young et al., 2013). These types of health system interventions on social risk factors may mitigate the effects of the social risk factors on certain health care outcomes, but they do not change the underlying social conditions. For example, if a hospital provides transportation services for patients to overcome barriers to transportation and to improve access to health care services, this does not address problems in the underlying transportation system.

Although VBP programs have catalyzed health care providers and plans to address social risk factors in health care delivery through their focus on improving health care outcomes and controlling costs, the role of social risk factors in producing health care outcomes is not reflected in payment under current VBP design. This misalignment has led to concerns that trends toward VBP could result in tangible harms to socially at-risk populations.

An emerging body of evidence suggests that providers disproportionately serving socially at-risk populations are more likely to score poorly on performance and quality rankings, more likely to be penalized, and less likely to receive bonus payments under VBP. Evidence suggests that this is true for safety-net providers who disproportionately serve low-income and other socially at-risk populations (Berenson and Shih, 2012; Gilman et al., 2014, 2015; Joynt and Jha, 2013; Rajaram et al., 2015; Williams et al., 2014), minority-serving institutions that serve high proportions of racial and ethnic minorities (Karve et al., 2008; Mehta et al., 2008; Shih et al., 2015), and critical access hospitals that serve rural areas (Joynt and Jha, 2011; Joynt et al., 2011, 2013; Lutfiyya et al., 2007), as well as primary care practices with more vulnerable populations (Friedberg et al., 2010). A Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) analysis of the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program also found that not only were hospitals serving the most low-income patients more likely to be penalized, but that their average penalty was substantially greater than that of hospitals serving the fewest low-income patients (MedPAC, 2013). Because these types of providers are historically less well reimbursed and therefore have fewer resources to begin with, by disproportionately penalizing them, VBP may be taking resources from the organizations that need them the most (Chien et al., 2007; Ryan, 2013).

Because patients with more social risk factors may require more resources to achieve the same outcomes as more advantaged patients, VBP that does not account for social risk factors may undervalue the resources and effort required to provide high-quality care to patients with high social risk factors (Chien et al., 2007). Consequently, it may be difficult for these providers to gain (or not lose) revenue (Joynt et al., 2014). In so doing, VBP may widen the resource gap between providers (Joynt et al., 2014). This may lead to deterioration in the quality of care, and VBP may have the unintended consequence of increasing health disparities (Bhalla and Kalkut, 2010; Chien et al., 2007; Cunningham et al., 2008; Joynt and Rosenthal, 2012; Joynt et al., 2014; Ryan, 2013; Volpp et al., 2006; Woolhandler and Himmelstein, 2015). Moreover, over the long term, revenue shortfalls to which more and greater penalties under VBP may contribute could lead to the closure of provider practices that serve socially at-risk populations (including hospitals, clinics, and physician offices) (Kane et al., 2012; Lipstein and Dunagan, 2014). Such closures would reduce access to care for patients with social risk factors (Bazzoli et al., 2012; Buchmueller et al., 2006; Walker et al., 2011).

If covering patients with social risk factors makes it more difficult to achieve quality ratings on par with plans serving fewer patients with social risk factors, this may also lead insurers to avoid covering socially at-risk populations and to leave markets (Joynt and Jha, 2013; Young et al., 2014). Consequently, enrollees may face higher premiums (Gaynor and Town, 2011). Relatedly, if penalties are larger than hospital margins to care for patients with social risk factors, this could reduce incentives to treat socially at-risk populations (Joynt and Jha, 2013). Such incentives to avoid serving patients with social risk factors would result in reduced access to care for these patients.

Finally, for providers and plans that serve populations including patients with both high and low levels of social risk factors, because it is more difficult to achieve quality benchmarks for patients with high social risk factors, these providers and plans may find incentives to improve care for patients with low levels of social risk factors only (Casalino et al., 2007). As a result, patients with high social risk factors may have barriers accessing high-quality care, which could in turn widen disparities.

One proposal to address the documented harms of the status quo under current VBP is to account for social risk factors in quality measurement and/or payment. Currently, to ensure accurate comparisons, VBP models account for underlying clinical risk factors known to independently drive variation in performance and to differ systematically across providers and therefore could statistically bias measured performance. Proposals to account for social risk factors extend the rationale of accounting for clinical risk factors in performance measurement and payment by also including

social risk factors as underlying patient characteristics that independently influence performance indicators and that differ systematically across providers and thus lead to bias in measured performance.

Proponents of this method cite the unintended consequences of the status quo—disproportionate penalties on providers serving socially at-risk populations and incentives to avoid patients with social risk factors, which could reduce quality and access and increase disparities—as rationale for accounting for the influence of social risk factors on performance indicators in VBP. Opponents of accounting for social risk factors acknowledge the potential influence of social risk factors on performance indicators in VBP, but argue that providers should be held accountable for providing care that mitigates the effect of social risk factors on health care outcomes. Proponents of accounting for social risk factors might counter that because social risk factors are difficult to address through provider action, providers should not be held accountable for them (Boozary et al., 2015; Feemster and Au, 2014; Fiscella et al., 2014; Girotti et al., 2014; Jha and Zaslavsky, 2014; Joynt and Jha, 2013; Lipstein and Dunagan, 2014; Pollack, 2013; Renacci, 2014).

Opponents of accounting for social risk factors are also worried that, because observed differences in quality reflect both the influence of social risk factors and true differences in the quality of care provided but cannot be quantitatively separated, accounting for social risk factors may obscure disparities (Krumholz and Bernheim, 2014). Consequently, this would institutionalize a poor standard of care for socially at-risk populations and also reduce incentives to improve quality and outcomes for them (Bernheim, 2014; Kertesz, 2014; Krumholz and Bernheim, 2014; O’Kane, 2015). Proponents suggest that, if observed differences for patients with social risk factors are observed consistently across the health care system, providers disproportionately serving socially at-risk populations should not bear the full financial penalty as they appear to under the status quo (Girotti et al., 2014).

A number of preliminary analyses have examined the effect of including social risk factors in risk adjustments. Several studies have found that adding socioeconomic status (SES) and other social risk factors would not substantively change risk adjustments and thus quality rankings (Bernheim et al., 2016; Blum et al., 2014; Eapen et al., 2015; Keyhani et al., 2014; Martsolf et al., 2016). In some cases, the lack of effect may reflect measurement issues. For example, studies often used area-level measures of SES (e.g., median household income) as proxies for individual-level effects and found no effect (Bernheim et al., 2016; Blum et al., 2014; Eapen et al., 2015; Keyhani et al., 2014; Martsolf et al., 2016). As described in the committee’s fourth report on data, geospatial units like counties and even zip codes are likely to be too heterogeneous to be useful (NASEM, 2016c).

There is also difference in interpretation as to what constitutes a meaningful effect (Bernheim et al., 2016; Gerrard, 2016; Grover, 2016; Kind et al., 2016).

Other studies found that including SES and other social risk factors in risk adjustments had a strong effect on quality rankings (Fiscella and Franks, 1999, 2001; Franks and Fiscella, 2002; Glance et al., 2016; Maney et al., 2007; Nagasako et al., 2014; Reidhead and Kuhn, 2016). One study reported a more nuanced effect, where incorporating social risk factors had little effect on most providers’ quality scores, but a substantial effect on a few (Zaslavsky and Epstein, 2005). Relatedly, one study found that, under the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, social risk factors explained some but not all of the increased readmission rates seen among safety-net hospitals (Sheingold et al., 2016). One study found that including patient characteristics in payment adjustments (but not performance measure scores) would reduce payment disparities (Damberg et al., 2015). Note that these studies, which found substantial effects of including social risk factors in risk adjustments of quality rankings, are not without measurement issues, such as the use of imperfect proxies to assess socioeconomic disadvantage (e.g., Damberg et al., 2015; Franks and Fiscella, 2002; Glance et al., 2016; Zaslavsky and Epstein, 2005).

STATEMENT OF TASK

HHS acting through the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) contracted with the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to convene an ad hoc committee to do the following:

- Provide a definition of socioeconomic status for the purposes of application to Medicare quality measurement and payment programs;

- Identify the social factors that have been shown to affect health outcomes of Medicare beneficiaries;

- Specify criteria that could be used in determining which social factors should be accounted for in Medicare quality measurement and payment programs;

- Identify methods that could be used in the application of these social factors to quality measurement and/or payment methodologies; and

- Recommend existing or new sources of data and/or strategies for data collection.

The committee comprises expertise in health care quality, clinical medicine, health services research, health disparities, social determinants of

health, risk adjustment, and Medicare programs (see Appendix F for the biographical sketches).

This report is the fifth and final report in a series of five brief reports that aim to inform ASPE analyses that account for social risk factors in Medicare payment programs mandated through the Improving Medicare Post-Acute Care Transformation (IMPACT) Act. In the first report, the committee presented a conceptual framework and described the results of a literature search linking five social risk factors and health literacy to health-related measures of importance to Medicare quality measurement and payment programs. In the second report, the committee reviewed the performance of providers disproportionately serving socially at-risk populations, discussed drivers of variations in performance, and identified six community-informed and patient-centered systems practices that show promise to improve care for socially at-risk populations. The committee’s third report identified social risk factors that could be considered for inclusion in Medicare quality measurement and payment, criteria to identify these factors, and methods to account for them in ways that can promote health equity and improve care for all patients. The fourth report provided guidance on where to find and how to collect data on social risk factor indicators that could be used for Medicare quality measurement and payment programs. Details of the statement of task and the sequence of reports can be found in Box 1-1. Notably, it is beyond the committee’s task to recommend whether social risk factors should be accounted for in Medicare VBP. The committee’s reports detail what the ASPE and CMS could do if they choose to do so.

THE COMMITTEE’S APPROACH

This final report draws together the committee’s previous reports; provides some additional context around and clarity about the committee’s findings, conclusions, and recommendations, and offers some guidance on implementation issues that may arise. The committee emphasizes that any approach to accounting for social risk factors should do so in a manner that can improve care and promote equity for all patients, especially those with social risk factors. As presented in its third report (NASEM, 2016b), the committee’s four goals in accounting for social risk factors in Medicare payment programs are

- Reducing disparities in access, quality, and outcomes;

- Quality improvement and efficient care delivery for all patients;

- Fair and accurate reporting; and

- Compensating providers fairly.

The following sections review the approach the committee took to identify relevant indicators and data sources based on sections of its first, third, and fourth reports. The committee’s processes for identifying methods to account for social risk factors in Medicare payment (from its third report) and systems practices for the care of socially at-risk populations (from its second report) are described in Chapters 3 and 4, respectively.

Identifying Social Risk Factors and a Conceptual Framework

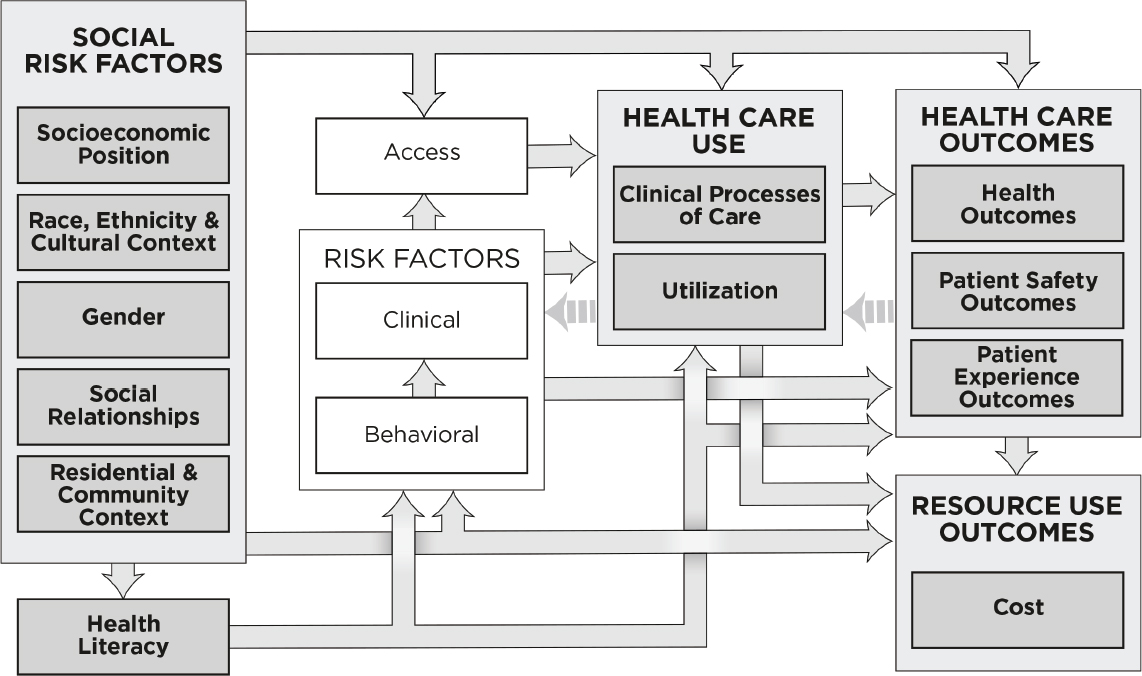

The committee’s first report, Accounting for Social Risk Factors in Medicare Payment: Identifying Social Risk Factors, presented a conceptual framework illustrating the primary hypothesized relationships between five domains of social risk factors plus health literacy and the health outcomes of Medicare beneficiaries (NASEM, 2016a) (see Figure 1-1). Because the committee’s task aims to inform Medicare VBP programs, the committee interpreted “health outcomes” as encompassing three domains of performance indicators used in Medicare VBP, which the committee roughly categorizes as health care use, health care outcomes, and resource use. Health care use encompasses clinical processes of care and health care utilization. Health care outcomes include health outcomes, patient safety outcomes, and patient experience outcomes. Resource use comprises costs. Similarly, the committee interpreted “socioeconomic status” and “other social factors” from its charge broadly to encompass five domains of social risk factors: SEP; race, ethnicity, and cultural context; gender; social relationships; and residential and community context (NASEM, 2016a).

The conceptual framework implies that social risk factors may influence performance indicators used in VBP in many interrelated ways. To provide empirical evidence to support these hypothesized relationships, the committee presented results of a literature search to identify social risk factors that have been shown to influence performance indicators used in VBP such as measures of health care use, health care outcomes, and health care costs. The committee uses the term influence to describe an association between a social risk factor and health care use or outcome measures without implying a causal association. The complete results of the literature search can be found in Appendix AA. In sum, and as will be discussed in Chapter 2, the committee identified literature showing that indicators of each of the five social risk factors and health literacy may influence the health care use, health care outcomes, and health care costs of Medicare beneficiaries (NASEM, 2016a). All other things being equal, the social composition of the population a health care provider or health plan serves can certainly influence that provider or plan’s performance (in terms of health care use, health care outcomes, and cost).

NOTE: This conceptual framework illustrates primary hypothesized conceptual relationships.

Selection Criteria for Possible Inclusion of a Social Risk Factor in VBP

The selection criteria aim to minimize the influence of social risk factors as patient characteristics that may influence performance indicators used in VBP independently of provider actions, and thus to promote accuracy in performance measurement. In other words, the criteria seek to guide selection of social risk factors that could be accounted for in Medicare quality measurement and payment such that providers (or health plans) are rewarded for delivering quality and value independently of the patients (or enrollees) they serve. Box 1-2 lists the three overarching considerations and five criteria that could be used to determine whether a social risk factor should be accounted for in performance indicators used in Medicare VBP programs.1 Descriptions of the criteria along with their rationale, potential limitations, and practical considerations for applying the criteria can be found in Appendix C.

The committee takes the opportunity to expand on the criterion that a social risk factor is not modifiable through provider actions. The rationale for this criterion is to exclude factors that are the consequence of care and therefore reflect genuine differences in the quality of care. Whether a social risk factor is modifiable or unmodifiable is not binary, but rather describes a spectrum of effects. Thus, it can be challenging to identify where a given social risk factor lies on this spectrum, particularly as health care providers and plans are increasingly addressing social risk factors for poor health outcomes. To guide this task, it is critical to distinguish between factors that can be modified themselves and factors that are not modifiable themselves, but whose effects on health can be mitigated through provider actions (such as use of tailored interventions) without altering the underlying disadvantage.

For example, for individuals with limited health literacy, evidence-based methods to improve patient health literacy exist (Berkman, 2011) and health literate health care organizations can align health care system demands with patient capacities to reduce barriers for patients to access, understand, and use health care information and services (Brach et al., 2012; IOM, 2012). Thus, health literacy is itself modifiable, as something that providers can influence and that can be a consequence of the quality of care provided. By comparison, for patients and enrollees whose preferred language is not English, providers and plans can tailor care such as by providing language interpreters and written materials in languages other than English. This may help patients to overcome language barriers by improving communication between providers and patients or plans and enrollees, and which may lead to improved quality and outcomes. However, doing

___________________

1 See Conclusion 1 in the committee’s third report (NASEM, 2016b).

so addresses language barriers without changing the underlying language skills of patients and enrollees.

The third report expanded the social risk factor framework presented in the first report to include specific indicators of each of the five domains of social risk factors. Indicators are ways to measure the underlying construct that differ from individual measures. For example, income is an indicator of socioeconomic position that can be measured in many ways (e.g., continuous or categorical measures of individual or household income, as annual income or lifetime earnings, etc.). After applying the selection criteria to these indicators, the committee concluded that there are measureable social risk factors that could be accounted for in the short or long term.2 The rationale for the selection or exclusion of each social risk factor indicator is detailed in Chapter 2 and Appendix C.

___________________

2 See Conclusions 2 and 3 in the committee’s third report (NASEM, 2016b).

Data Sources

The committee’s fourth report takes the social risk factor indicators identified in the third report that could be accounted for in Medicare VBP programs in the short and long term and identifies data sources and data collection strategies CMS could use to account for social risk factors in Medicare payment if it chooses to do so. The committee identified three categories of data sources: (1) new and existing sources of CMS data; (2) data from providers and plans; and (3) alternative government data sources.3

Existing sources of CMS data include administrative records (enrollment records and claims data) and beneficiary surveys with limited social risk factor data, such as beneficiaries’ race and ethnicity (ResDAC, n.d.). If CMS collected new social risk factor data, it could design measures and data collection methods that would ensure collection of accurate data that meet the needs of the intended method to account for those social risk factor indicators in Medicare performance measurement and payment programs. Importantly, such new data collection on social risk factors need not be restricted to Medicare quality measurement and payment applications. CMS could also use these data for other purposes, including research and quality improvement.

For social risk factor indicators that are relevant and relatively stable (for example, race and ethnicity, language, and education), the committee recommends that CMS collect new social risk factor information at the time of enrollment (NASEM, 2016c).4 Additionally, if research shows an important explanatory effect of a social risk factor indicator and a pilot test shows it feasible, CMS could supplement the new social risk factor information collected at the time of enrollment with a universal survey of current beneficiaries, whose social risk factor information would not have been captured at enrollment.

The committee recognizes the substantial barriers of collecting new data, including cost and burden. At the same time, the committee documented tangible if unintended, adverse consequences of the VBP status quo (which generally does not account for social risk factors). The committee also found that accounting for social risk factors could mitigate these adverse consequences. The need to mitigate unintended consequences of the status quo could justify the expected costs and burden of new data collection. Furthermore, because it is also important to monitor any approach to accounting for social risk factors to ensure unintended, adverse consequences for health disparities do not arise, such data collection would also facilitate such monitoring for both new approaches and under the status

___________________

3 The committee deemed private data sources out of scope, because CMS would have to purchase it at unknown cost and because data collection methods may not be fully transparent.

4 See Recommendation 7 in the committee’s fourth report (NASEM, 2016c).

quo. Other uses of such social risk factor data such as to target quality improvement initiatives and to inform the development and implementation of appropriately tailored interventions (CMS, 2016) provide additional rationale for CMS to collect such data.

Data from providers and plans include electronic health record (EHR) data and administrative data. Providers and plans that care for and cover Medicare beneficiaries already send these data to CMS. Some social risk factor data (for example, race and ethnicity and language) are already captured in some EHRs and some administrative data (IOM, 2014; Lawson et al., 2011; Nerenz et al., 2013a,b). New social risk factor data that providers and plans could collect could also be important for the care or services providers and plans provide (IOM, 2014). Furthermore, collecting social risk factor information from providers and plans could increase burdens on providers and plans (including the need for infrastructure upgrades), as well as patients and enrollees (IOM, 2014). In particular, patients and enrollees may not know or be willing to disclose information on their social risk factors, and efforts to gather such information may raise concerns about privacy and the security of their health and social risk factor information, especially if such data are used for nonclinical purposes (such as for quality measurement and payment) (IOM, 2014).

Alternative government data refer to administrative data and national surveys that federal agencies other than CMS (including other agencies within HHS) and state agencies oversee and maintain that contain information on social risk factors and that CMS could use. These include data that could be linked to Medicare beneficiary data at the individual level, area-level data that could be used to describe a Medicare beneficiary’s residential environment or serve as a proxy for individual level effects, and data CMS could use to determine how to elicit social risk factor information from Medicare beneficiaries. The Social Security Administration may be the best source of individual-level social risk factor data that could be linked to Medicare beneficiary data. The American Community Survey may be most useful as a source of area-level social risk factor data.

Patients are the underlying source of social risk factor data for each of the three categories of sources. For some social risk factors like race, ethnicity, and gender, it is important for patients to self-identify. However, CMS, health care providers and health plans, and government agencies collect and maintain social risk factor information and—more importantly—standardize, assess, interpret, and report this information in a valid, consistent, and reliable way. In the future, new and better methods of data collection could emerge (e.g., methods that are more accurate, less burdensome, or less costly). As these methods emerge, an ideal system would be responsive to evolving data availability and could adapt to use new data sources.

The committee evaluated data from these three categories of sources with respect to three characteristics:

- Collection burden, or resources, including cost and effort required to collect and store data on the part of CMS, providers/health plans, and respondents;

- Accuracy, or the extent to which a given measure captures the construct that measure represents, as well as elements of data validity, reliability, and completeness; and

- Clinical usefulness, meaning whether providers can use social risk factor information in the management and treatment of patients (IOM, 2014).

The committee also considered whether an indicator is relatively stable (such as race and ethnicity) or changes over time (such as social support). The committee recommended five guiding principles CMS should use when choosing data sources for specific indicators of social risk to be used in Medicare performance measurement and payment (see Box 1-3).5

Data from any source have advantages and disadvantages with respect to the three characteristics (collection burden, accuracy, and clinical utility) that must be balanced. Thus, selection of any data source requires certain trade-offs. After considering data sources for each social risk factor with respect to the three characteristics (collection burden, accuracy, and clinical utility) and five principles, the committee recommended specific data CMS could use to account for social risk factors in Medicare VBP if it so chooses. This will be discussed in Chapter 2.

OVERVIEW OF THIS REPORT

This report synthesizes and elaborates on the committee’s first four reports. Chapter 2 briefly defines each social risk factor and identifies data sources for social risk factors that meet the selection criteria. Chapter 3 discusses the methods to account for social risk factors in Medicare payment programs, and also addresses some issues that may arise when implementing those methods. Chapter 4 discusses ways in which ASPE and CMS could move forward with accounting for social risk factors in Medicare VBP programs, should they choose to do so. Appendixes A, B, C, and D reproduce the committee’s previous reports in order and in their entirety.

___________________

5 See Recommendation 1 in the committee’s fourth report (NASEM, 2016c).

REFERENCES

Alley, D. E., C. N. Asomugha, P. H. Conway, and D. M. Sanghavi. 2016. Accountable health communities—addressing social needs through Medicare and Medicaid. New England Journal of Medicine 374(1):8-11.

Bazzoli, G. J., W. Lee, H. M. Hsieh, and L. R. Mobley. 2012. The effects of safety-net hospital closures and conversions on patient travel distance to hospital services. Health Services Research 47(1pt1):129-150.

Berenson, J., and A. Shih. 2012. Higher readmissions at safety-net hospitals and potential policy solutions. Issue Brief (Commonwealth Fund) 34:1-16.

Berkman, N. D. 2011. Health literacy interventions and outcomes: An updated systematic review. Vol. 199. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

Bernheim, S. M. 2014. Measuring quality and enacting policy: Readmission rates and socioeconomic factors. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes 7(3):350-352.

Bernheim, S. M., C. S. Parzynski, L. Horwitz, Z. Lin, M. J. Araas, J. S. Ross, E. E. Drye, L. G. Suter, S. L. Normand, and H. M. Krumholz. 2016. Accounting for patients’ socioeconomic status does not change hospital readmission rates. Health Affairs (Millwood) 35(8):1461-1470.

Berwick, D. M. 2011a. Launching accountable care organizations—the Proposed Rule for the Medicare Shared Savings Program. New England Journal of Medicine 364(16):e32.

Berwick, D. M. 2011b. Making good on ACO’s promise—the Final Rule for the Medicare Shared Savings Program. New England Journal of Medicine 365(19):1753-1756.

Bhalla, R., and G. Kalkut. 2010. Could Medicare readmission policy exacerbate health care system inequity? Annals of Internal Medicine 152(2):114-117.

Blum, A. B., N. N. Egorova, E. A. Sosunov, A. C. Gelijns, E. DuPree, A. J. Moskowitz, A. D. Federman, D. D. Ascheim, and S. Keyhani. 2014. Impact of socioeconomic status measures on hospital profiling in New York City. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes 7(3):391-397.

Boozary, A. S., J. Manchin, 3rd, and R. F. Wicker. 2015. The Medicare Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program: Time for reform. Journal of the American Medical Association 314(4):347-348.

Brach, C., D. Keller, L. M. Hernandez, C. Baur, B. Dreyer, P. Schyve, A. J. Lemerise, and D. Schillinger. 2012. Ten attributes of health literate health care organizations. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Braveman, P., and S. Gruskin. 2003. Defining equity in health. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 57(4):254-258.

Buchmueller, T. C., M. Jacobson, and C. Wold. 2006. How far to the hospital?: The effect of hospital closures on access to care. Journal of Health Economics 25(4):740-761.

Burwell, S. M. 2015. Setting value-based payment goals—HHS efforts to improve U.S. Healthcare. New England Journal of Medicine 372(10):897-899.

Casalino, L. P., A. Elster, A. Eisenberg, E. Lewis, J. Montgomery, and D. Ramos. 2007. Will pay-for-performance and quality reporting affect health care disparities? Health Affairs (Millwood) 26(3):w405-w414.

Casalino, L. P., N. Erb, M. S. Joshi, and S. M. Shortell. 2015. Accountable care organizations and population health organizations. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 40(4):821-837.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2015. Health equity. http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/healthequity (accessed February 16, 2016).

Chien, A. T., M. H. Chin, A. M. Davis, and L. P. Casalino. 2007. Pay for performance, public reporting, and racial disparities in health care: How are programs being designed? Medical Care Research and Review 64(5 Suppl):283s-304s.

CMS (Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services). 2016. CMS OMH statistics and data: Part C and D performance data stratified by race and ethnicity. https://www.cms.gov/About-CMS/Agency-Information/OMH/research-and-data/statistics-and-data/stratifiedreporting.html (accessed October 27, 2016).

Cunningham, P. J., G. J. Bazzoli, and A. Katz. 2008. Caught in the competitive crossfire: Safety-net providers balance margin and mission in a profit-driven health care market. Health Affairs (Millwood) 27(5):w374-w382.

Damberg, C. L., M. N. Elliott, and B. A. Ewing. 2015. Pay-for-performance schemes that use patient and provider categories would reduce payment disparities. Health Affairs (Millwood) 34(1):134-142.

Eapen, Z. J., L. A. McCoy, G. C. Fonarow, C. W. Yancy, M. L. Miranda, E. D. Peterson, R. M. Califf, and A. F. Hernandez. 2015. Utility of socioeconomic status in predicting 30-day outcomes after heart failure hospitalization. Circulation: Heart Failure 8(3):473-480.

Elliott, M. N., A. M. Zaslavsky, E. Goldstein, W. Lehrman, K. Hambarsoomians, M. K. Beckett, and L. Giordano. 2009. Effects of survey mode, patient mix, and nonresponse on cahps hospital survey scores. Health Services Research 44(2 Pt 1):501-518.

Feemster, L. C., and D. H. Au. 2014. Penalizing hospitals for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease readmissions. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 189(6):634-639.

Fiscella, K., and P. Franks. 1999. Influence of patient education on profiles of physician practices. Annals of Internal Medicine 131(10):745-751.

Fiscella, K., and P. Franks. 2001. Impact of patient socioeconomic status on physician profiles: A comparison of census-derived and individual measures. Medical Care 39(1):8-14.

Fiscella, K., H. R. Burstin, and D. R. Nerenz. 2014. Quality measures and sociodemographic risk factors: To adjust or not to adjust. Journal of American Medical Association 312(24):2615-2616.

Franks, P., and K. Fiscella. 2002. Effect of patient socioeconomic status on physician profiles for prevention, disease management, and diagnostic testing costs. Medical Care 40(8):717-724.

Friedberg, M. W., D. G. Safran, K. Coltin, M. Dresser, and E. C. Schneider. 2010. Paying for performance in primary care: Potential impact on practices and disparities. Health Affairs (Millwood) 29(5):926-932.

Gaynor, M., and R. J. Town. 2011. Competition in health care markets. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Gerrard, P. B. 2016. Accounting for socioeconomic status does change readmission rates. Health Affairs (Millwood) 35(8):1461-1470.

Gilman, M., E. K. Adams, J. M. Hockenberry, I. B. Wilson, A. S. Milstein, and E. R. Becker. 2014. California safety-net hospitals likely to be penalized by ACA value, readmission, and meaningful-use programs. Health Affairs (Millwood) 33(8):1314-1322.

Gilman, M., E. K. Adams, J. M. Hockenberry, A. S. Milstein, I. B. Wilson, and E. R. Becker. 2015. Safety-net hospitals more likely than other hospitals to fare poorly under Medicare’s value-based purchasing. Health Affairs (Millwood) 34(3):398-405.

Girotti, M. E., T. Shih, S. Revels, and J. B. Dimick. 2014. Racial disparities in readmissions and site of care for major surgery. JAMA Surgery 218(3):423-430.

Glance, L. G., A. L. Kellermann, T. M. Osler, Y. Li, W. Li, and A. W. Dick. 2016. Impact of risk adjustment for socioeconomic status on risk-adjusted surgical readmission rates. Annals of Surgery 263(4):698-704.

Grover, A. 2016. Study data do point to a significant SES role in readmissions. http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/35/8/1461.long/reply#healthaff_el_478026 (accessed November 3, 2016).

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2016. HHS reaches goal of tying 30 percent of Medicare payments to quality ahead of schedule. Washington, DC: HHS Press Office.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2001. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2012. How can health care organizations become more health literate?: Workshop summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2014. Capturing social and behavioral domains and measures in electronic health records: Phase 2. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IRS (Internal Revenue Service). 2016. New requirements for 501(c)(3) hospitals under the Affordable Care Act. https://www.irs.gov/charities-non-profits/charitable-organizations/new-requirements-for-501c3-hospitals-under-the-affordable-care-act (accessed November 3, 2016).

Jha, A. K., and A. M. Zaslavsky. 2014. Quality reporting that addresses disparities in health care. Journal of the American Medical Association 312(3):225-226.

Joynt, K. E., and A. K. Jha. 2011. Who has higher readmission rates for heart failure, and why? Implications for efforts to improve care using financial incentives. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes 4(1):53-59.

Joynt, K. E., and A. K. Jha. 2013. A path forward on Medicare readmissions. New England Journal of Medicine 368(13):1175-1177.

Joynt, K. E., and M. B. Rosenthal. 2012. Hospital value-based purchasing: Will Medicare’s new policy exacerbate disparities? Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes 5(2):148-149.

Joynt, K. E., E. J. Orav, and A. K. Jha. 2011. Thirty-day readmission rates for Medicare beneficiaries by race and site of care. Journal of the American Medical Association 305(7):675-681.

Joynt, K. E., E. J. Orav, and A. K. Jha. 2013. Mortality rates for Medicare beneficiaries admitted to critical access and non-critical access hospitals, 2002-2010. Journal of the American Medical Association 309(13):1379-1387.

Joynt, K. E., N. Sarma, A. M. Epstein, A. K. Jha, and J. S. Weissman. 2014. Challenges in reducing readmissions: Lessons from leadership and frontline personnel at eight minority-serving hospitals. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety 40(10):435-435.

Kane, N. M., S. J. Singer, J. R. Clark, K. Eeckloo, and M. Valentine. 2012. Strained local and state government finances among current realities that threaten public hospitals’ profitability. Health Affairs (Millwood) 31(8):1680-1689.

Karve, A. M., F. S. Ou, B. L. Lytle, and E. D. Peterson. 2008. Potential unintended financial consequences of pay-for-performance on the quality of care for minority patients. American Heart Journal 155(3):571-576.

Kautter, J., G. C. Pope, M. Ingber, S. Freeman, L. Patterson, M. Cohen, and P. Keenan. 2014. The HHS-HCC risk adjustment model for individual and small group markets under the Affordable Care Act. Medicare & Medicaid Research Review 4(3).

Kertesz, K. 2014. Center for Medicare Advocacy comments on the impact of dual eligibility on MA and Part D quality scores. http://www.medicareadvocacy.org/center-for-medicare-advocacy-comments-on-the-impact-of-dual-eligibility-on-ma-and-part-d-quality-scores (accessed December 20, 2016).

Keyhani, S., L. J. Myers, E. Cheng, P. Hebert, L. S. Williams, and D. M. Bravata. 2014. Effect of clinical and social risk factors on hospital profiling for stroke readmission: A cohort study. Annals of Internal Medicine 161(11):775-784.

Kind, A. J., S. Jencks, J. Brock, and T. N. Pindyck. 2016. Methodological limitations due to SES measures and geographic linkages. http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/35/8/1461.long/reply#healthaff_el_478026 (accessed November 3, 2016).

Kindig, D., and G. Stoddart. 2003. What is population health? American Journal of Public Health 93(3):380-383.

Krumholz, H. M., and S. M. Bernheim. 2014. Considering the role of socioeconomic status in hospital outcomes measures. Annals of Internal Medicine 161(11):833-834.

Lawson, E. H., R. Carreón, G. Veselovskiy, and J. J. Escarce. 2011. Collection of language data and services provided by health plans. American Journal of Managed Care 17(12):e479-e487.

Lipstein, S. H., and W. C. Dunagan. 2014. The risks of not adjusting performance measures for sociodemographic factors. Annals of Internal Medicine 161(8):594-596.

Lutfiyya, N. M., D. K. Bhat, S. R. Gandhi, C. Nguyen, V. L. Weidenbacher-Hoper, and M. S. Lipsky. 2007. A comparison of quality of care indicators in urban acute care hospitals and rural critical access hospitals in the United States. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 19(3):141-149.

Maney, M., C. L. Tseng, M. M. Safford, D. R. Miller, and L. M. Pogach. 2007. Impact of self-reported patient characteristics upon assessment of glycemic control in the Veterans Health Administration. Diabetes Care 30(2):245-251.

Martsolf, G. R., M. L. Barrett, A. J. Weiss, R. Kandrack, R. Washington, C. A. Steiner, A. Mehrotra, N. F. SooHoo, and R. Coffey. 2016. Impact of race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status on risk-adjusted hospital readmission rates following hip and knee arthroplasty. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 98(16):1385-1391.

MedPAC (Medicare Payment Advisory Commission). 2013. Report to the Congress: Medicare and the health care delivery system. Washington, DC: MedPAC.

Mehta, R. H., L. Liang, A. M. Karve, A. F. Hernandez, J. S. Rumsfeld, G. C. Fonarow, and E. D. Peterson. 2008. Association of patient case-mix adjustment, hospital process performance rankings, and eligibility for financial incentives. Journal of the American Medical Association 300(16):1897-1903.

Minyard, K. 2016. Public health 3.0: Innovation spreads as we are bridging for health. https://health.gov/news/blog/2016/09/public-health-3-0-innovation-spreads-as-we-are-bridging-for-health (accessed October 31, 2016).

Nagasako, E. M., M. Reidhead, B. Waterman, and W. C. Dunagan. 2014. Adding socioeconomic data to hospital readmissions calculations may produce more useful results. Health Affairs (Millwood) 33(5):786-791.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2016a. Accounting for social risk factors in Medicare payment: Identifying social risk factors. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2016b. Accounting for social risk factors in Medicare payment: Criteria, factors, and methods. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2016c. Accounting for social risk factors in Medicare payment: Data. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2016d. Systems practices for the care of socially at-risk populations. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Nerenz, D. R., R. Carreon, and G. Veselovskiy. 2013a. Race, ethnicity, and language data collection by health plans: Findings from 2010 AHIPF-RWJF survey. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 24(4):1769-1783.

Nerenz, D. R., G. M. Veselovskiy, and R. Carreon. 2013b. Collection of data on race/ethnicity and language proficiency of providers. American Journal of Managed Care 19(12):e408-e414.

Nikpay, S. S., and J. Z. Ayanian. 2015. Hospital charity care—effects of new communitybenefit requirements. New England Journal of Medicine 373(18):1687-1690.

O’Kane, M. 2015. Comment on the advance notice of methodological changes for calendar year 2016 for Medicare Advantage call letter. http://www.ncqa.org/public-policy/comment-letters/medicare-advantage-03-2015 (accessed December 20, 2016).

O’Malley, A. J., A. M. Zaslavsky, M. N. Elliott, L. Zaborski, and P. D. Cleary. 2005. Case-mix adjustment of the CAHPS hospital survey. Health Services Research 40(6 Pt 2):2162-2181.

Pollack, R. 2013. CMS-1599-p, Medicare program; hospital Inpatient Prospective Payment Systems for acute care hospitals and the long-term care hospital Prospective Payment System and proposed fiscal year 2014 rates; quality reporting requirements for specific providers; hospital conditions of participation; Medicare program; Proposed Rule. Vol. 78, no. 91: Letter to the CMS Administrator Tavenner. http://www.aha.org/advocacy-issues/letter/2013/130620-cl-cms-1599p.pdf (accessed December 20, 2016).

Pope, G. C., J. Kautter, R. P. Ellis, A. S. Ash, J. Z. Ayanian, M. J. Ingber, J. M. Levy, and J. Robst. 2004. Risk adjustment of Medicare capitation payments using the CMS-HCC model. Health Care Financing Review 25(4):119-141.

Rajaram, R., J. W. Chung, C. V. Kinnier, C. Barnard, S. Mohanty, E. S. Pavey, M. C. McHugh, and K. Y. Bilimoria. 2015. Hospital characteristics associated with penalties in the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program. Journal of the American Medical Association 314(4):375-383.

Reidhead, M., and H. B. Kuhn. 2016. Before penalizing hospitals, account for social determinants of health. http://catalyst.nejm.org/penalizing-hospitals-account-social-determinants-of-health (accessed September 19, 2016).

Renacci, J. B. 2014. Letter to HHS Secretary Burwell and CMS Administrator Tavenner regarding the Medicare Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. http://tinyurl.com/q6shyoc (accessed December 20, 2016).

ResDAC (Research Data Assistance Center). n.d. Health and Retirement Survey- Medicare linked data. https://www.resdac.org/cms-data/files/hrs-medicare (accessed August 4, 2016).

Rosenbaum, S. 2015. Additional requirements for charitable hospitals: Final rules on community health needs assessments and financial assistance. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2015/01/23/additional-requirements-for-charitable-hospitals-final-rules-on-community-health-needs-assessments-and-financial-assistance (accessed November 3, 2016).

Rosenthal, M. B. 2008. Beyond pay for performance—emerging models of provider-payment reform. New England Journal of Medicine 359(12):1197-1200.

Ryan, A. M. 2013. Will value-based purchasing increase disparities in care? New England Journal of Medicine 369(26):2472-2474.

Sheingold, S. H., R. Zuckerman, and A. Shartzer. 2016. Understanding Medicare hospital readmission rates and differing penalties between safety-net and other hospitals. Health Affairs (Millwood) 35(1):124-131.

Shih, T., A. M. Ryan, A. A. Gonzalez, and J. B. Dimick. 2015. Medicare’s Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program in surgery may disproportionately affect minority-serving hospitals. Annals of Surgery 261(6):1027-1031.

Volpp, K. G., A. J. Epstein, and S. V. Williams. 2006. The effect of market reform on racial differences in hospital mortality. Journal of General Internal Medicine 21(11):1198-1202.

Walker, K. O., R. Clarke, G. Ryan, and A. F. Brown. 2011. Effect of closure of a local safety-net hospital on primary care physicians’ perceptions of their role in patient care. Annals of Family Medicine 9(6):496-503.

Williams, K. A., Sr., A. A. Javed, M. S. Hamid, and A. M. Williams. 2014. Medicare readmission penalties in Detroit. New England Journal of Medicine 371(11):1077-1078.

Woolhandler, S., and D. U. Himmelstein. 2015. Collateral damage: Pay-for-performance initiatives and safety-net hospitals. Annals of Internal Medicine 163(6):473-474.

Young, G. J., C. H. Chou, J. Alexander, S. Y. Lee, and E. Raver. 2013. Provision of community benefits by tax-exempt U.S. hospitals. New England Journal of Medicine 368(16):1519-1527.

Young, G. J., N. M. Rickles, C. H. Chou, and E. Raver. 2014. Socioeconomic characteristics of enrollees appear to influence performance scores for Medicare Part D contractors. Health Affairs (Millwood) 33(1):140-146.

Zaslavsky, A. M., and A. M. Epstein. 2005. How patients’ sociodemographic characteristics affect comparisons of competing health plans in California on HEDIS quality measures. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 17(1):67-74.