The workshop began with a keynote presentation by Susan Phillips, who understands accreditation from multiple viewpoints. She has worked in a regulatory capacity in health professional accreditation and educational quality assurance, and she has received accreditation services as a university provost and a senior vice president of an academic health center.

ACCREDITATION: REALITIES, CHALLENGES, AND OPPORTUNITIES

Susan D. Phillips, Ph.D.

University at Albany, State University of New York

Susan Phillips, professor of counseling psychology of the University at Albany, State University of New York, began her presentation by explaining that accreditation refers to a process for external quality review used by higher education to scrutinize colleges, universities, and educational programs for quality assurance and quality improvement (Eaton, 2011). Accreditation also refers to a status; it provides public notification that an institution or program has met the accepted standards of quality that has been judged acceptable or higher by profession-specific education experts (ASPA, 2013).

The source of standards, the evaluation unit, and the focus of accreditation may differ for each country and region. In many countries, quality assurance in higher education is based on national or ministerial standards, and it is undertaken by a governmental ministry or a national quality agency. In the United States, accreditation is outside of the governmental structure, and it is focused on professionally driven standards carried out in nongovernmental associations, with peer review undertaken by volunteers. Some accreditation systems are more focused on quality assurance (compliance with standards), whereas others are more focused on quality improvement. In the United States, there is a focus on both compliance and improvement.

Role of Accreditation

Phillips stated that accreditation confers an academic legitimacy on the institution or program in question. It advances academic quality, it demonstrates accountability, and it encourages purposeful change and needed improvement. However, Phillips said, there are many expectations of this seal of approval. For example, students look to accreditation to provide confidence that they chose to pursue a good program, and that the program meets its educational goals. It may also provide students eligibility to access a licensure or certification process in their professions, she said. The

expectation for programs and institutions is that accreditation will provide accountability, recognition that the program or institution is achieving its goals, and recognition that the program or institution is providing the quality of education mandated by the profession. Accreditation provides a framework for regular review and evaluation. It guides the program or institution to continuous improvement and process, and addresses innovation and change. Phillips said that accreditation also protects the institution or program from guidance from the outside—at times, accreditation may prohibit an institution from implementing well-meaning but misguided ideas about how a profession should work.

For the health professions, accreditation represents a concurrence within the profession about what academic quality means for that particular profession. It codifies what the profession expects in terms of the preparation of its practitioners, both in terms of process and outcome. It can also define the gates for entry into practice. Lastly, for policy makers and the public, it can provide confidence that quality education is being provided, which is a particularly important role when there is public or governmental financial investment in that education.

Challenges for Accreditation

While each of the functions described are reasonable expectations for a quality assurance and quality improvement process, said Phillips, there are also hopes and expectations placed on accreditation. In the United States, there are more students in higher education than ever, there is a wider range of preparation for those students, there are many types of programs offered to those students, and there are numerous ways to educate those students. There are new kinds of institutions, such as public, private, for-profit, embedded, and freestanding. There is also more money being directed toward higher education—more than $150 billion per year from the federal government, states, and localities (The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2015). These circumstances bring new hopes that the accreditation process will answer questions that it was never intended to ask, she said. For example, students and families ask: Can I afford this? Will I ever graduate? Will I get a job? Will I make enough money to live? Will I repay my loans? Policy makers ask: Are students learning what we want them to learn? Are they completing their programs? Can they pay back their loans?

Phillips focused on two main challenges for accreditors: first, challenges from and for the profession, and second, challenges from and for the larger governmental regulatory context.

Challenges Relating to the Profession

Accreditation of professional preparation can have great influence; quality assurance can shape the resources and curriculum of professional preparation and ensure that students are treated fairly and educated well, and quality improvement can keep educators and professionals mindful of their progress in figuring out how to do things differently and better. However, said Phillips, accreditation cannot define the perfect direction of the profession, nor can accreditation hold back the profession’s growth. While accreditation of professional preparation programs can ensure that students are receiving what the profession thinks is necessary for entry into practice, accreditation alone cannot decide what those standards are. Accreditation can reflect the concurrence of the professional community and its educators when through the convening and guidance of the accreditor, these two groups are brought together to reach that concurrence, she said. The federal standards from the U.S. Department of Education, for example, state that an accreditation agency must demonstrate that its standards, policies, procedures, and decisions are widely accepted by educators and educational institutions and by licensing bodies, practitioners, and employers in the professional fields for which the students are prepared.1

Phillips presented two examples of statements that reflect this. In physical therapy education, the comprehensive curriculum plan is based on information about the contemporary practice of physical therapy, standards of practice, and the current literature, publications, and other resources related to the profession (CAPTE, 2016)—none of which are created by the accreditor. The American Association of Colleges of Nursing’s Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education’s statement describes the goals for determining the accreditation standards—specifically, “enabling the community of interest to participate in significant ways in the review, formulation, and validation of accreditation standards and policies and in determining the reliability of the conduct of the accreditation process” (CCNE, 2013). Each of the accreditation standards in the profession has a statement such as these, said Phillips. Professions and their accreditors need to work together and be right in step.

The relationship between the profession, its accreditors, and its educators is an ongoing conversation and a continual challenge in which each element has a critical role, Phillips explained. The profession’s role is to reflect practice now and to envision how professional practice will evolve going forward; the educators’ roles are to translate the needed competencies now and in going forward into a vibrant educational plan; and the accredi-

___________________

1 For more information about the U.S. Department of Education’s federal standards, see www2.ed.gov/admins/finaid/accred/accreditation_pg13.html (accessed September 21, 2016).

tors’ roles are to reflect and hold up the concurrence across the profession and its stakeholders about what is needed in quality preparation. While a given individual may play all of these roles, it is important to consider the different functions for each category of individuals.

At times, professions and educators face challenges when accreditation standards seem to limit what they can do. Phillips suggests that in these circumstances, the professional community and educators think about what level of innovation is needed and how best to include this innovation in the accreditation system. One challenge faced by accreditors is how to convene the best conversation across all of the perspectives, both informally and ongoing, but also as required formally by government at regular intervals.

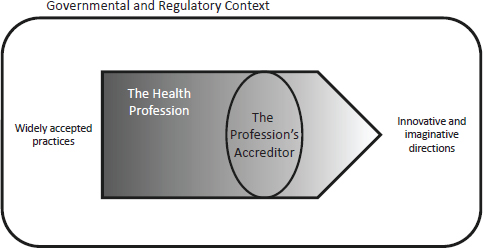

Phillips presented Figure 2-1 to show how she views the relationship between a profession and its accreditor. The arrow pointing to the right shows that the profession is in forward motion. The left side of the arrow represents what is considered “tried and true” to professional practice. As one moves toward the right of the figure, innovation and imagination begin to come into effect. For example, the first section represents discussions about the emerging need for better promotion of health and wellness, more

NOTES: The profession is moving forward and encompasses what is widely accepted, as well as innovation and imagination about where the profession might go in the future. The profession’s accreditor includes what is widely accepted in its standards. It also includes what is agreed upon as emerging in the profession; but it does not yet reach the far right side of the arrow. The box surrounding the arrow represents the governmental and regulatory context in which the professions and accreditation exist.

SOURCE: Adapted from Phillips, 2016.

interprofessional collaboration, and a shift from inpatient to community care. The next section to the right would represent those who think about emerging technologies and treatment tools, new patterns of comorbidity, emerging health care jobs, and new providers. And at the tip of the arrow are the very innovative, imaginative, and future-thinking individuals. The figure shows how health and health care practice are shifting, showing the spectrum of “tried and true” to completely visionary.

Accreditation, represented by the grey oval, exists somewhere in the middle of this spectrum. It reflects all that is tried and true, and what is agreed upon as emerging in the profession, but it does not quite reach the visionary and imaginative thinking represented at the front of the arrow. Those ideas may or may not become fully embraced by the profession.

Phillips noted that it is important to remember that ideas and issues may fall in different places on this spectrum across each profession, and may vary in their categorization at any moment. One of the challenges of the accreditor, educator, and profession is figuring out exactly where accreditation should be on the spectrum.

Challenges Relating to Government and Regulation

The second challenge Phillips described involves government and regulators. Each of the professions—architecture, drama, theology, or the various health care professions—operates in a particular governmental and regulatory context, she said. This is represented by the box around the arrow in Figure 2-1. This context is specific to each country. The government regulators have far less familiarity with the specifics of the professions, yet they have the responsibility for ensuring that accreditation—or at least the accountability, compliance, and quality assurance part of accreditation—has strong integrity and can be considered a reliable guarantor of educational quality.

The interests and concerns of government and regulators are broader than those of individual professions, said Phillips. This context presents a critical set of challenges for accreditation. Some of what the regulators expect of accreditation is very reasonable; for example, the insistence on professional engagement in the development and regular review of the quality standards. But some of the expectations are drawn from concerns that are much more removed from professional education, often relating to finances and learning outcomes; usually, these concerns are reflected in government or regulatory perspectives.

Phillips presented three examples of these concerns. First, she described governments’ and ministries’ desire to protect the student. Governments want to ensure that students are wise consumers who make informed choices about where their educational dollar is spent. The second example

Phillips described is the government’s desire to ensure that students learn and that targeted learning outcomes are achieved. While this is a common goal for all, it is difficult to agree on what those learning outcomes are and how they should be measured. The final example she gave was governments’ concern to protect the federal dollar investment in higher education, particularly in terms of a student being able to pay the loans they have received.

These are all legitimate concerns, but they expand beyond the purview of a single profession or even a group of professions. The questions and metrics that are posed, Phillips said, are more often directed to the accreditation of institutions and, particularly in the United States, undergraduate institutions. Nonetheless, professional education programs (both undergraduate and graduate) and their accreditors—despite their different scope, focus, and levels of education—tend to be treated in the same way. To function, the professions and their accreditors need to operate within this regulatory context, which creates many challenges.

Opportunities for Accreditation

Phillips saw many unique opportunities for this workshop of the Global Forum on Innovation in Health Professional Education (the Forum) because of its international, multiprofession, and multiaccreditor participation. In addition, she said, Forum members and workshop participants share a common goal of quality preparation for health professional practice. She recommended that participants remain mindful of the important but different roles of countries and governments, of different professions, of the educators, and of the accreditors. With those relationships in mind, she said, there are also opportunities to work together toward common goals, to share challenges and solutions so all can benefit from each other’s experiences, and to potentially collaborate on new solutions.

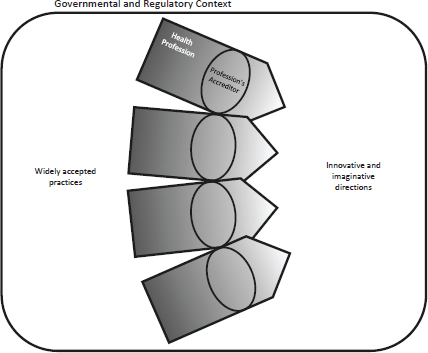

Phillips showed a second diagram (see Figure 2-2) to show that the health professions are both separate and coevolving. Their accreditors are represented by the grey circles, which all touch, and their larger government context wraps around them all.

Phillips highlighted three series of critical questions that she believes can and should be posed. First, she challenged stakeholders to envision how health care practice is evolving, and to then think about how this evolution could be reflected in professions, their practice, and their preparation. For example, she said, professions are thinking about innovative practices; emerging practitioner roles; new venues of practice; and changing roles of patient, family, and community in the profession. Are there intersections and commonalities across the professions at the visionary end of the arrows

NOTES: Each arrow represents a different health profession, as described in Figure 2-1. The ovals, representing the accreditation of each profession, all touch—meaning that they are all connected and related. The box surrounding the arrows represents the larger country governmental and regulatory context that each profession and its accreditation exist.

SOURCE: Adapted from Phillips, 2016.

in Figures 2-1 and 2-2 that eventually might move toward being part of the education of new professionals?

Her second series of questions related to the goal to turn needed practice competencies into educational plans. Phillips asked, how can we learn about emerging issues in practice in each profession, and how common issues are (or could be) addressed in professional education and reflected in the accreditation standards and processes? For instance, each profession identifies the need to practice in an interprofessional context. While that is a common issue, she said, it is addressed in different ways in different educational programs and is reflected differently in accreditation. She asked, what can we learn from each other in this that might improve our education and our practice?

The third series of questions focused on thinking together about educational programs and the accreditors reflecting these programs in quality standards and processes. How can we study the ways in which professions are learning about and addressing common issues in the education and training process? How are these reflected in the accreditation standards and processes, or how could they be? For example, she said, by addressing common issues in education and training, other questions are raised; how can we ensure the quality of clinical supervision? How can we provide flexibility for different ways in which programs are trying to implement a given standard? How can we ensure tolerance for trying out new things?

There are several other questions one could pose about the evolution of the health and health care professions, about the educational strategies to ensure practice competencies, and about the reflection of these in the accreditation standards and process. She suggested that to enrich the discussions, stakeholders should listen for the intersections and commonalities that exist in quality preparation among each profession and each country, and where they might intersect going forward.

Discussion

Following Phillips’s presentation, workshop co-chair Neil Harvison, American Occupational Therapy Association, opened the floor for questions and comments. Leading off the discussion was Malcolm Cox, University of Pennsylvania and former chief academic affiliations officer of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. He asked Phillips to comment on the tension across different professions’ accrediting bodies, which depends on where they are located in the arrow demonstrated in Figures 2-1 and 2-2. Cox noted that tension might be expected to be greatest when more traditional and more innovative accrediting bodies interact. Phillips noted that it is not the accreditors who place themselves in that spectrum between “tried and true” and visionary, but rather the call of the three players—the profession, the educators, and the accreditors—to find the right place for that particular profession. For example, she said, if a profession’s accreditation circle is too far to the left on the spectrum, it means the profession is not sufficiently engaged in the conversation about what constitutes quality education. This is what Phillips calls a diagnostic symptom, and balance needs to be sought to position the three players so all are contributing an equal force of movement. If a group of constituencies think that the set of standards is not acceptable, they should speak up and have that conversation with their accreditors.

Phillips suggested stakeholders look at the professions in which the accreditation circle is in the right place—where accreditation, the profession, and education are in harmony. She then recommended that stake-

holders examine the conversations that are happening among the players: how did they arrive at their standards, and how did they address where accreditation should fall on the spectrum? She gave an example of the American Psychological Association, where there were many visionary people wanting to put their ideas into the accreditation standards. While one might personally agree with what the visionaries believe and are doing to educate learners, the larger profession may be sitting more toward the “tried and true” end of the spectrum and may not be ready for the visionary ideas. In this case, there was a process in which a particular advocate for a curriculum component felt very strongly but did not engage the profession in collecting concurrence.

This example brought up the question of how professions address innovation. There are cultural differences within a profession that might make it useful to see how the exemplar professions have been able to bring together the “tried and true” and the visionary ideas through careful placement of accreditation. Harvison added that each profession’s dialogue addressing innovation within accreditation will vary depending on the culture of the individual profession. In some professions, there are many forums and opportunities to have these types of discussions before consensus is reached; whereas in other professions, these opportunities do not necessarily exist. What is important, he said, is how the dialogue between stakeholders is facilitated.

Roger Strasser, dean of the Northern Ontario School of Medicine in Canada, noted an apparent continuing development of notions and definitions of quality education. The accreditation enterprise itself is also evolving. To Strasser, the trend in accreditation is moving from a focus on structure and content to a focus on process and outcomes. He asked Phillips how she sees these developments coming together to an accreditation system that is functional and effective, and that may improve the value of accreditation to all the professions and bring the professions together to improve health care and health outcomes. Phillips agreed with Strasser’s points, and responded by first explaining that in the United States, accreditation started because of attempts to define what a college is. She noted some of the characteristics of what define a college—having a library, a faculty with certain qualifications, students, etc. These are what she calls “inputs to education.” In the 1980s or 1990s, she said, accreditation began to move away from only thinking about inputs to education to instead think more about outcomes of education. Accreditation began to ask, “What are students learning?”

Education outcomes are measured in many ways. In some cases, it is with a single test; other times, it is on multiple measures. Typically, accreditation programs have many outcomes they are looking to establish, and programs are using many metrics to understand these outcomes. Phillips noted that outcomes measurement is harder to do in the liberal arts under-

graduate institutions because outcomes are difficult to determine and they vary. However, health professions can measure specific competencies in the practice of the profession that are necessary for successful and good health care. These competencies can be reflected as outcomes in the programs, monitored, and then reflected in the accreditation process.

Warren Newton, American Board of Family Medicine, spoke about what he called the “burning issue in health care right now,” which is finding the right relationship between accreditation processes for institutions and certification processes for individuals. He stated that this is particularly an issue at the interface between organizations, teams, and individuals where quality can be improved. He asked Phillips who regulates this issue, and what she sees as the right relationship? Phillips responded by noting that she has seen this tension in her professional roles, and it is important to remember that accreditation focuses on the programs. While there are learners in those programs who hope to become licensed or certified, the specific learners, per se, are not necessarily considered when it comes to the accreditation of a program. She provided an example of what she called extreme—a program may prepare students to have all the competencies they would need to pass a certification test, and so a given student’s failure on this certification test would not necessarily mean the program was not of high quality. As far as Phillips is aware, no accreditation system has an outcome criterion for quality that includes a 100 percent pass rate on certification exams.

Individual certification, in turn, is focused on the individual capacity. Phillips considered it almost a form of accreditation by the certifiers. To bridge these conversations, she said, one should remember that licensing boards are part of constituencies. These certifiers are part of the constituencies that need to be in the standard development for accreditors, she said. Licensing boards are part of who needs to be at the table as the accreditation standards are developed.

Pamela Jeffries, dean of the George Washington University School of Nursing, asked Phillips what she saw as the “sweet spot” when all of the professions’ accreditors align, and what the metrics would be for measuring quality. When asked to provide exemplars of this, Phillips responded that she has not seen a set of professions that do this well. While collegiality and parallel play among accreditation, education, and professions does exist, she does not believe that there is yet a true incorporation of understanding about each other. In her mind, this is a huge challenge; conversations about best practices, common struggles and challenges, and feedback and metrics from graduates could enormously benefit the health professions.

Jan De Maeseneer from Ghent University in Belgium wondered to what extent accreditation processes should be contextualized according to the needs of the communities where the institution is working and how there can be a mix between universal dimensions and specific contextual dimen-

sions in accreditation, especially when it comes to issues such as social accountability and addressing the social health gap. Phillips responded by saying that any education program should have a sense of what body of work it is preparing its students for; it should have a sense of what the places, challenges, and cultures are of where students are typically sent. The programs understand the social context and can use this context as a laboratory for understanding, as well as an opportunity to educate students on how to adapt their learning to a different environment and context. In psychology, for example, the accreditation standards show attention to individual and cultural diversity. But, she said, accreditors, professionals, and educators then need to think about making a difference in their communities and improving the health of their communities. In her opinion, one of the most important resources that these stakeholders have is their graduates, from new professionals to seasoned professionals. These seasoned professionals understand, because of their lived experience, how to make a positive difference in their communities, and will be able to convey how their education might have better prepared them for this. Phillips believes that this information would be very valuable to academic programs, whose organizers could use the information to determine what innovations are needed in their programs and to implement these to better prepare their students.

David Benton, chief executive officer of the National Council of State Boards of Nursing, sees educational delivery becoming a transnational product that is being offered in an increasingly globalized context. Based on his experience working in a global organization, he noted that while focusing on the accreditation of the professions is important, it is not the only factor in play in relation to the care delivery environment, the educational environment, and some of the legal frameworks. Phillips agreed, saying that there are enormous amounts of regulation, and this is all included in the larger context of education, profession, and accreditation.

Peter H. Vlasses, Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education, described the Association of Specialized and Professional Accreditors, a network of accreditors that share best practices and are collectively looking at how to be on the side of innovation and visionary ideas. Association of Specialized and Professional Accreditors members frequently discuss the preparation of students and entry into practice, yet rarely do they discuss the continuing competence of seasoned professionals and continuing professional development, and the role of accreditation in that area—especially in the area of interprofessional education (IPE). According to Phillips, the rigor required to enter into professional practice is high, partly due to accreditation standards, but these expectations diminish significantly after the individual is a fully practicing professional. While there are continuing education requirements for professionals, there is concern that profession-

als will stop becoming competent or that they will not continue to develop with the growth of their profession. The profession has an opportunity to reflect on accreditation and build on the notion of continuing education or lifelong learning, but there is little ability to enforce this beyond the point of graduation or licensure. This, she said, is actually the same argument that universities have against tenure, because there are few regularized ways of ensuring continuing contribution. Phillips suggested the possible solution of professions renewing their license every several years, and including certain requirements or retraining programs that would have their own mid-career recertification accreditation process.

The final question came from Marilyn Chow of Kaiser Permanente. She wondered how consumers of health care, who are also stakeholders of accreditation, might have input into the accreditation process. In response, Phillips said that consumers may not define what the practice is, but they are stakeholders and ought to be at the table, which she believes is part of an ongoing conversation among professional accreditors. Phillips referred Chow and the participants to a session later in the workshop agenda where this issue is further addressed (see Chapter 4).

TRADE-OFFS FOR ACCREDITATION

Eric Holmboe from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education facilitated a discussion drawn from the Session II objective that questions what accreditation can and cannot realistically accomplish. According to Holmboe, such a conversation is necessary to begin to sort through the strongly held belief that adding a topic to the accreditation standards will improve education in that area contrasted with the belief that eliminating accreditation standards would remove the barriers to innovation and education reform.

To look at these opposing “add versus subtract” positions around standards, Holmboe asked the participants to talk among themselves for 10 minutes in groups of 8 persons or so to consider whether requiring attention to a topic through accreditation actually improves the quality of education in that area (see Box 2-1, question 1). Individuals reported their discussions to the larger group.

Question 1: Will Requiring Attention to a Topic Through Accreditation Actually Improve the Quality of Education in That Area?

Zohray Talib from George Washington University led off the reports with reactions to the first question stating that improving quality through increased attention would require a collective vision and definition of quality and would depend on the type of attention required. For example,

addressing social determinants of health2 or IPE requires first a clear vision that is agreed upon by everyone involved (i.e., accreditors, academics, professionals in the field, and government) and then consideration of what attention means so accreditors do not resort to simple checklists that lack any degree of flexibility. The combined vision also requires a clear, collective understanding of quality and a set of desired outcomes that can be used to measure degrees of improvement. Like Talib, Miguel Paniagua from the National Board of Medical Examiners reported using IPE as one of the frames to discuss this question. In response to whether requiring attention to a topic through accreditation will improve the quality of education, he said, “It depends, it’s possible, and it’s quite likely,” conveying that answers to this question are highly contextually dependent and conditional in nature. Paniagua then emphasized a desire to see accreditors move past individual professional identities to work jointly on something like IPE; however, strict and loose interpretations of IPE competencies by different accrediting bodies could be a source of tension. Without specificity, competency-based requirements are left to interpretation, but being more prescriptive lessens the flexibility of individual institutions for innovation. The key, he said, is to strike a balance, but the question is where and how.

Katie Eliot with the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics agreed with Paniagua’s point that accreditation’s ability to improve quality of education is contextually dependent, adding that addressing quality raises other issues such as the need to educate the educators, the difference in how constituencies define quality, how the definition of quality is shared with educators, and where the line between assurance and quality exists. To start to address these questions, it is important to know how any decision affects relevant

___________________

2Social determinants of health are “the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age, including the health system. These circumstances are shaped by the distribution of money, power, and resources at global, national, and local levels, which are themselves influenced by policy choices. The social determinates of health are mostly responsible for health inequities—the unfair and avoidable differences in health status seen within and between countries” (WHO, 2016).

programs and professions. For example, one might strive to strike a balance in accreditation that does not limit programs and takes into account how the agreed upon balance affects patients and other constituents.

Sara Fletcher with the Physician Assistant Education Association responded that requiring attention to a topic through accreditation could improve the quality of education, but not necessarily. Attention to a topic through accreditation provides focus, and such a focus would hopefully lead to uncovering exemplars of quality, she said. For this to happen, there would have to be a focus on the topic, the process, the examples, the outcomes, and the measurement of quality. All aspects of the topic—how it is introduced to how it is evaluated—would have to be considered as well as the resources that would be needed to accomplish the desired outcomes. Fletcher used the example of preceptor shortages at clinical sites to make her point. She asked the audience to imagine a day when across the health professions there is a shared commitment for embracing the concept of profession-neutral preceptors—a model that de-emphasizes the importance of the professional identity of preceptors and instead focuses on the learning that needs to occur. In this model, physician assistant students may have dentists as preceptors, and nursing students could have physicians as preceptors, as long as the learning objectives are met. She followed by saying that though this may make sense from an educational vantage point, gaining traction for this idea in the broader academy of the health professions will require much more than attention to the topic through accreditation.

The Jonas Center for Nursing and Veterans Healthcare representative, Darlene Curley, reported very similar perspectives as those previously stated, and also stated that requiring attention to a topic is just the first step that must happen. Quality improvement depends on how the topic is implemented and what the outcomes are for patients, clients, and communities. Holly Wise from the American Council of Academic Physical Therapy responded that requiring attention to a topic through accreditation can improve quality of education in that area, but it will be frustratingly slow. She also reflected on the diagram presented by Susan Phillips in her opening remarks (see Figure 2-1). In particular, she noted the content or topic that was on the right edge of that circle of accreditation are the topics that are moving forward but not yet operationalized. Then she contemplated the direction of the arrows outside of the circle and whether they ultimately converge or diverge knowing that divergence would make the process even slower, especially for broader-themed topics. Finally, Wise raised the question of responsibility, asking “who is responsible for operationalizing the topic of interest?” Is it the accreditors’ responsibility to demand it of the professions that are giving the input, or is it something that evolves from the profession? Regardless of who initiates it, making sure practitioners are part of the discussion would ensure that it is not solely academicians providing input.

Holmboe then asked the participants to resume their small group discussions to consider the second question (see Box 2-1, question 2) on recognizing quality improvement in education.

Question 2: How Can an Accrediting Agency Know If an Added Topic or New Criterion Actually Improved the Quality of Education? Should There Be Some Sort of Litmus Test?

Zohray Talib’s initial response to the question centered around individual programs. If a new criterion were required of a single program, improvements in quality would likely be gauged through self-evaluation, as there may not be a specific metric of performance but rather a required process the program would have to follow. Talib then considered it from an aggregate view. Her table’s discussion and debate led her to report that in the short term one could again look at a process evaluation but in the medium and longer term, there might be practice analysis changes or health service delivery environment changes that could be used as measures of quality improvement in education.

Miguel Paniagua’s report was again informed by his group’s discussion where he admitted coming up with more questions than answers. He began by asking whether accrediting agencies would be the first to know whether an added topic or criterion improved education quality, and whether the question should be rephrased to say that the criterion should actually not focus on the quality of education, but the quality of care? His final question was about how to define quality and whether quality should be determined by outcomes of people served. Paniagua used the Triple Aim3 as an example, but he was quick to clarify that many other definitions of quality exist, and it would be good to know which ones are most meaningful to patients. Holmboe asked how Paniagua would link the quality of education with the quality of care given the growing evidence that those two are intertwined? Paniagua agreed that both are equally important and mutually dependent, and he added that both would be measured.

Building on Paniagua’s comments and list of questions, Pamela Jeffries from George Washington University added that knowing quality would depend on the topic, who judges the quality of education, and how outcomes are measured. She brought up the notion of adaptive testing saying that in nursing there is computer-based adaptive testing. This kind of testing adjusts questions based on the ability level of the individual taking the examination (Glossary of Education Reform, 2014). But this is just one

___________________

3 The Institute for Healthcare Improvement Triple Aim is a framework for health system performance involving (1) better patient care, (2) improved population health, and (3) reduced health care costs (IHI, 2016).

method for testing competency, said Jeffries, adding that many items go into proving competency in a defined area. When discussing quality of care, Jeffries suggested having the patient’s or client’s voice as part of educational assessment; in the same regard, she raised questions about whether patients have the understanding of quality to be able to judge competency within education. Likely some things they can judge and some things they cannot, she added, before going on to say that practitioners are another important group to include in the accreditation process. They may be best positioned to know whether a learner’s performance meets a certain standard. The final set of measures Jeffries called out were assessing knowledge, skills, and attitude that go into quality education and care, as well as fitness for purpose and student progression.

Darlene Curley emphasized the importance of clinical patient care for assessing quality thus elevating the importance of the practice component for monitoring such quality. To better ensure continuity, Curley reported the suggestion of having the same topic criteria threaded through education and practice accreditation. It might start with The Joint Commission identifying an item that is then incorporated into education accreditation.

In reporting her group’s discussion, Maria Tassone from the University of Toronto emphasized the issue of a “litmus test.” There is a need for some sort of litmus test, she said, but that delaying progress because the perfect test is not immediately available would be counterproductive. The example she provided to emphasize her point was problem-based learning. It has been used for 30 years, yet there is no evidence beyond the level-1 Kirkpatrick model—personal reactions to the educational experience—that it actually works.4 While this example demonstrates that the intervention is “tried,” it is lacking in evidence to say that it is “true.” The suggestion she offered is to not wait until everything is perfect but to build in measurement and evaluation right from the beginning. One could perhaps start with more proximal or process measures before moving toward the more distal outcomes like patient quality and safety that involve different kinds of testing approaches, both qualitative and quantitative. Tassone closed with recognition of the accreditation community by saying that accreditors are good at monitoring quality assurance, but providing input for quality improvement presents a challenge given the current accreditation structure. To move in this direction from assurance to improvement would require a culture shift involving all the stakeholders, which could be done but would be a large undertaking.

___________________

4Donald Kirkpatrick (1959, 1967, 1994) training evaluation model is frequently used as a model for the evaluation of learning interventions. For more information about the Kirkpatrick model, see http://www.kirkpatrickpartners.com/OurPhilosophy/TheKirkpatrickModel (accessed September 21, 2016).

Summary of the Session

Holmboe summarized the session by bringing out three important themes he personally gleaned from each of the reporters’ responses to the two questions. For question one, he said that it is not enough to identify a particular topic of education to be addressed through accreditation standards. There are issues that surround the topic—such as the accreditor’s role in implementation and whether the accreditor provides guidance on quality improvements or a pathway to implementation—that also need to be considered. Should the accreditor be the driver of quality improvement or might that be the responsibility of the educators or a separate entity? There are different ways of doing quality improvement, but according to Holmboe this notion of who drives quality in education was an important area of discussion. Another key area Holmboe identified involved alignment. The concept he explained aligns education with patient care through accreditation that goes beyond just the programs and individuals but includes institutions like hospitals and The Joint Commission.5 A final reflection offered by Holmboe harkened back to a comment made by Maria Tassone of the University of Toronto to build evaluation into education right from the beginning and, as she said, walk on the bridge as it is being built.

Warren Newton from the American Board of Family Medicine added to Holmboe’s reflections by digging deeper into the issue of implementation and the importance of thinking through how institutions will address implementation, which is critical in determining whether or not to move forward. Tassone also provided additional thoughts on the idea of the interface between practice and education by drilling down on who the stakeholders are that actually inform the accreditation process, and how to better ensure that the practice community is at the table. Malcolm Cox, University of Pennsylvania and former chief academic affiliations officer of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, shared a similar view as Tassone indicating that one of the most important commonalities he thinks about is better alignment between educators and the delivery system. Such alignment is critical for determining how to frame outcomes that are increasingly moving beyond health care delivery itself and toward the health and well-being of individuals and populations. According to Cox, there is a much broader alignment issue, one that represents concepts of health and well-being as opposed to health care alone. John Weeks, representing Academic Collaborative for Integrative Health, referred the group to a recent article, “Era 3 for Medicine and Health Care,” by Donald Berwick (2016), that finds the current health care environment uses measurements not for quality improvement but for rewarding and punishing professionals. This caused Weeks to

___________________

5 For more information about The Joint Commission, see www.jointcommission.org (accessed September 21, 2016).

wonder whether too much oversight and regulation is contributing to the stress and burnout of health care administrators and health professionals. Holmboe speculated that such challenges may actually be opportunities to think more strategically about alignment across accreditors around topics such as stress and burnout, IPE, and the social determinants of health that are important to all the health professions. Holmboe stated maybe that is a good starting place for different accreditors to come together.

PROFESSIONAL DRIVERS OF ACCREDITATION

Neil Harvison from the American Occupational Therapy Association opened the session that included two debates.6

The First Debate

The first debate was moderated by Rick Talbott of the Association of Schools of Allied Health Professions. It looked at how accreditation could be a motivator for educators to innovate, and, conversely, how accreditation might cause obstructions to innovations in education. In his introductory remarks, Talbott alluded to debates conducted at previous Forum workshops that were used to demonstrate pedagogy while raising challenging and sometimes contentious issues. He then reviewed the structure that his and the following debate would use while also introducing his debaters. Elizabeth Hoppe from the Association of Schools and Colleges of Optometry argued for the side that accreditation hinders innovation, and Karen Wolf from the Pennsylvania State University College of Nursing took the opposing position that accreditation does not hinder innovation.

Workshop participants, he said, would have 1 minute to cast their votes for which side of the debate they aligned with. The voting would then be followed by 9 minutes of lively and entertaining points brought up by each of the two debaters before the participants again cast their votes to see if the debate arguments changed any participants’ views, and to hear from the debaters their true feelings on the topic.

Participant Perspectives

The debate provided fodder for an in depth discussion with the debaters. Eric Holmboe started by questioning Wolf about her use of the term respon-

___________________

6 Videos of the debates and the discussions that proceeded can be found on the Global Forum on Innovation in Health Professional Education workshop website, www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Activities/Global/InnovationHealthProfEducation/2016-APR-21 (accessed September 21, 2016).

sible innovation.7 Wolf responded that her use of the term involved looking at how accreditors and educators think about best practice evidence to support innovations. For instance, there are a range of innovations that are not necessarily good ideas. They need to be thought through and the evidence reviewed before integrating untested innovations that do not have a well-balanced base of support. At the same time, she added, flexibility is needed to support laboratories that try new ideas and in the process of implementing such innovations, the evaluative aspects of the innovation need to be examined to avoid widespread replication before the innovation has been tested.

In keeping with the theme of innovation, Susan Scrimshaw, the president of The Sage Colleges, questioned the speed of accreditation change as it relates to innovation. In general, there are long intervals between when criteria for accreditation are reviewed and when the implementation phase begins. This can take years. Given that, Scrimshaw asked whether the system can move quickly enough for accreditation to support innovation in a rapidly changing environment? The challenge, Wolf said, is to provide enough flexibility in the standards, structures, and processes to assure that time constraints are not major barriers to responsible innovation.

Roger Strasser from the Northern Ontario School of Medicine in Canada made the observation that some people in education view the accreditation process very negatively. They see it as a strict mandate being forced upon them and if they do not conform to the defined requirements, they will suffer grave consequences. Hoppe responded to Strasser’s remarks from her own experiences both as a founding dean and an accreditation site visitor. From the accreditor’s perspective, Hoppe was sensitive to the notion that accrediting bodies could support innovation; however, her experiences as a founding dean pushed her to the opposing view. Before she could recruit her first student or develop promotional materials, Hoppe had to meet accreditation standards that changed throughout the approval process. In addition, every 2 years she was required to perform a full self-study: there is a full site visit, there are in-depth reports that must be completed, and there are special focus site visits that must be attended. Hoppe also brought up the challenges of interprofessional, collaborative programs. She pointed out one particularly innovative college on her campus that constantly experiences tensions and ongoing difficulties with their accrediting agency. Based on what she has witnessed and gone through as a founding dean combined with her understanding about the importance of obtaining and maintaining accreditation, Hoppe admitted her inclination toward delaying approval of innovations proposed

___________________

7 According to the KARIM (Knowledge Acceleration and Responsible Innovation Meta-network) project, responsible innovation is “an iterative process throughout which a project’s impacts on social, economic and environmental factors are measured where possible and otherwise taken into account at each step of project development” (KARIM, 2016).

by her faculty. Her reluctance to approve is not because her program is not ready for innovations but rather because of the very close scrutiny she receives and the rigorous assessment her program continues to undergo. She also pointed out the difference between being at a well-established institution versus a new institution like her own. We can innovate, she said, just not yet.

Debater’s Comments

For the last segment of the debate, Talbott asked each of the debaters to indicate their true opinions about the debate proposition. Hoppe went first. She started by describing the value of accreditation, that it gives programs structure and that programs benefit from the process. But because it is not what they are set up to do and because of her own personal experiences, she does not believe it is the accreditor’s job to innovate. Talbott then turned to Wolf, who offered her view that it is the role of accreditation not to block or hinder innovation. In fact, there are times when it is appropriate to support innovation—for example, in terms of social accountability both locally and globally. What is important for her is flexibility in the standards and encouraging accreditors to have conversations that support common language and standards, and perhaps joint competencies. This may be one way to minimize repetitiveness across the health professions and possibly a way of bringing the different professions together that maximizes resources.

The Second Debate

Neil Harvison then thanked the first debate team and turned to Holly Wise of the American Council of Academic Physical Therapy to moderate the second debate. She began by explaining the proposition that involves examining benefits and risks associated with accreditation for health professional education in low-resource environments. The two debaters were Nelson Sewankambo from Makerere University in Uganda and Warren Newton from the American Board of Family Medicine. Sewankambo presented the position that accreditation stimulates progress in low-resource settings, and Newton argued the opposing side that accreditation does not stimulate progress in low-resource settings.

Participant Perspectives

In a similar structure to the previous debate, a group discussion followed the stated arguments. Malcolm Cox commented first. He was struck by Newton’s description of the unintended consequences of the Flexner report (Flexner, 1910) that moved to a university-based system of health professional education. While many of the post-Flexner shifts were posi-

tive, it also resulted in the closure of all three medical schools for women and all but two of the seven schools educating African Americans (Finkel, 2013). An additional unforeseen consequence, Cox noted, was the halting of community-based or community-engaged education leading to present-day challenges of how to implement and fund learning in and with communities. Cox’s remarks were followed by a question from David Benton representing the National Council of State Boards of Nursing. He prefaced his question to Sewankambo with a caution that when looking at accreditation, one needs to avoid getting stuck in a particular paradigm. The example he gave involved the use of technology for education. Benton encourages anyone interested in using this medium to first study how low- and middle-income countries, such as countries in sub-Saharan Africa, creatively employ technologies, rather than rely solely on the experiences of highly developed countries such as those in Australia, North America, or the United Kingdom. In drawing the link to accreditation, Benton said it is about making sure that accreditation systems can stimulate a development, which means having the flexibility to take advantage of opportunities that promote progress rather than being “stuck in the past.” Sewankambo responded that low- and middle-income countries need to ensure that the accreditation process is structured, designed, and understood by accreditors in ways that appreciate what accreditation should do and not stifle progress or innovation. Similarly, the educational institutions need to understand how they can work within a flexible accreditation system that takes advantage of innovations while also achieving specific requirements set up through the accreditation process.

Following Sewankambo, Mary Barger spoke as a representative of the American College of Nurse-Midwives. She added that the entire profession of midwifery to the list of casualties following the Flexner report. She pointed out the importance of midwives as women’s care providers within the community, although she voted in favor of the proposition that accreditation stimulates progress in low-resource countries. She did so because of her experience where she saw firsthand how accreditation can inspire low-resource countries to move away from short-sighted, quick fixes that result in poorly trained midwives to high-quality programs that produce midwives who can care for 95 percent of the needs of a childbearing woman and her newborn. Barger pointed out how politically difficult it can be to enforce such standards. But, she added, having the backing of an international accreditation body makes it somewhat easier knowing that higher-quality training will lead to higher-quality outcomes for women and their families.

To Jan De Maeseneer from Ghent University in Belgium, it is the context that dictates whether accreditation in low-resource areas can stimulate progress or not. De Maeseneer provided numerous examples from countries in Africa, Bolivia, Brazil, and countries in Europe where unaccredited, for-

profit institutions at times deliver diplomas with no clinical training requirements or, in other instances, award diplomas with the backing of a central bank rather than the Ministries of Health and Education. In those cases, he is a proponent of international accreditation not necessarily to close those tracks, but to consider giving guidance for how the facility might improve its educational practices. He used the previously cited Flexner report to make his point. The African American and women’s medical schools in North America that were closed because of the Flexner report should not have been closed; rather, they should have been supported to build their capacity so they could achieve high-quality goals and standards. To him, the answer is social accountability. It involves mobilizing the resources that can help schools serving communities of need become institutions providing high-quality training of the health workforce for those communities.

The last participant comment came from Gary Filerman of the Atlas Health Foundation who offered a word of caution to those who voted in favor of international accreditation standards. In his opinion, globalizing the product or the process of accreditation is a mischievous conversation in many regards. He used nursing as an example, stating that the profession has driven hard the notion that there is such a thing as an international standard for global nursing education. This has led some countries to inappropriately invest in nursing education for export to more developed countries. Such international standards may not be entirely appropriate for the nursing needs of that country, which led him to believe that obtaining international accreditation has to do with achieving status that he sees as irrelevant and essentially mischievous.

Debater’s Comments

Following Filerman’s remark, Wise gave the debaters an opportunity to make any final analysis about the debate proposition. Sewankambo led by restating his belief that accreditation can stimulate progress in developing country institutions provided the accreditation is done well and considers the context within which the institutions are functioning. He did not agree with the immediate closure of schools in the United States following the publication of the Flexner report. Institutions should have been given a specified time period within which to improve, but Sewankambo was quick to add that if a school is so bad that it is likely to do more harm than good to the population, that school must be closed. He pointed out the explosion in the number of for-profit health professional institutions now appearing in low- and middle-income countries. There is a need for ensuring these institutions will not be a risk to the population, he said, as might well be the case if there are no quality standards in place that can be overseen through an accreditation process.

Newton finished the discussion by stating his true position that an accreditation system is needed, and the issue is how to operationalize the process and navigate the tension between standards and available resources. Is it the process quality assurance (in which all institutions that do not meet standards suffer consequences) or quality improvement (in which there is a constructive discourse between schools and accreditors)? He expressed interest in how to use accreditation to learn about educational interventions then disseminate best practices. And while progress may be slow, Newton was heartened by Florida State University and Northern Ontario School of Medicine, who he believes have revolutionized medical school accreditation over the last number of years. It took them half a generation to have an impact but these two examples demonstrate that change is indeed possible. On that note, he returned the floor to Holmboe who closed the session.

REFERENCES

ASPA (Association of Specialized and Professional Accreditors). 2013. Quick reference: Standards, outcomes, and quality. Chicago, IL: Association of Specialized and Professional Accreditors.

Berwick, D. M. 2016. Era 3 for medicine and health care. JAMA 315(13):1329-1330.

CAPTE (Commission on Accreditation in Physical Therapy Education). 2016. Standards and required elements for accreditation of physical therapist assistant education programs. Alexandria, VA: CAPTE.

CCNE (Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education). 2013. Standards for accreditation of baccalaureate and graduate nursing programs. Washington, DC: CCNE.

Eaton, J. S. 2011. An overview of U.S. accreditation. Washington, DC: Council for Higher Education Accreditation.

Finkel, M. L. 2013. Public health in the 21st century. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

Flexner, A. 1910. Medical education in the United States and Canada. Washington, DC: Science and Health Publications, Inc.

Glossary of Education Reform. 2014. Computeradaptive test. http://www.edglossary.org/ computer-adaptive-test (accessed September 21, 2016).

IHI (Institute for Healthcare Improvement). 2016. The IHI Triple Aim.http://www.ihi.org/offerings/Initiatives/TripleAIM (accessed September 21, 2016).

KARIM (Knowledge Acceleration and Responsible Innovation Meta-network). 2016. http://www.karimnetwork.com/about (accessed September 21, 2016).

Kirkpatrick, D. L. 1959. Techniques for evaluating training programs. Journal of American Society of Training Directors 13(11):3-9.

Kirkpatrick, D. L. 1967. Evaluation of training. In Training and development handbook, edited by R. L. Craig and L. R. Bittel. New York: McGraw-Hill. Pp. 87-112.

Kirkpatrick, D. L. 1994. Evaluating training programs: The four levels. 1st ed. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.

The Pew Charitable Trusts. 2015. Federal and state funding of higher education: A changing landscape. Washington, DC: The Pew Charitable Trusts. http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2015/06/federal-and-state-funding-of-higher-education (accessed September 21, 2016).

Phillips, S. 2016. Accreditation: Realities, challenges, and opportunities. Presented at the workshop: The Role of Accreditation in Enhancing Quality and Innovation in Health Professions Education. Washington, DC, April 21.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2016. Social determinants of health. http://www.who.int/topics/social_determinants/en (accessed September 21, 2016).

This page intentionally left blank.