C

Environmental Scan

Submitted to:

Health and Medicine Division and Transportation Research Board

By: Heidi Guenin, A.I.C.P., M.P.H.

This environmental scan was supported by the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) and commissioned by the Health and Medicine Division (HMD) and the Transportation Research Board (TRB), program divisions of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Heidi Guenin conducted the interviews and wrote this report. Special thanks to Ross Peterson, Principal of GridWorks, for providing input and feedback on this report.

The views in this environmental scan do not reflect the views of FTA, HMD, or TRB. For more information, contact Heidi Guenin at (503) 841-7936 or heidi@groxie.com.

PURPOSE

This environmental scan was conducted to support the Health and Medicine Division and the Transportation Research Board workshop: Exploring Data and Metrics of Value at the Intersection of Health Care and Transportation.1

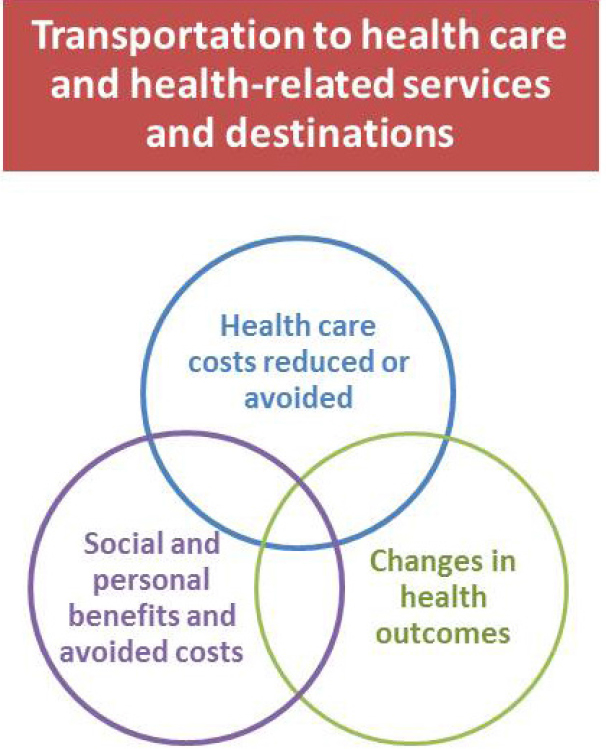

Transportation impacts health outcomes directly, especially through physical activity, safety, and air quality (see Figure C-1). Transportation also impacts access to health care directly, and through access to care, transportation also affects health care costs and health outcomes indirectly. The purpose of this scan is to examine if and how transportation and health care partners explore the return on investment of providing transportation to health care or health-related destinations. More than 70 individuals were interviewed about health care and transportation partnerships, relevant data, and the value proposition of providing transportation to health care and health-related destinations.

BACKGROUND

Transportation is well understood to be a significant factor in health care access. There are many ways that individuals access health care and other health supportive services, including walking, bicycling, riding fixed-route transit (e.g., bus or subway), using a taxi cab or shared ride service, or calling an ambulance. While some individuals have financial, physical, and cultural access to these transportation options and more, others have few to no transportation options to help them access health care. As a direct result they may delay or miss preventive or primary care appointments, not make it for follow-up care, or may be unable to fill prescriptions or access other health supports.

Individuals enrolled in Medicaid can obtain transportation (nonemergency medical transportation, or NEMT) to their Medicaid-covered appointments as part of their benefit, while individuals who are not insured, insured through Medicare, or who have private insurance are responsible for their own ride. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) requires transit agencies to provide paratransit for individuals who are not able to use the fixed-route bus (guidelines for eligibility are set at the federal level and made more specific by individual agencies). Paratransit service must be available during the same hours as fixed-route service and available to pick individuals up and drop them off up to three-quarters of a mile off of the fixed route. Veterans have access to transportation to U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care facilities; more than 100 of the 153 VA

___________________

1 The workshop is part of a project sponsored by the Federal Transit Administration.

health care centers around the country have a mobility manager on staff to help veterans access transportation. Through the Veterans Transportation Service (VTS), veterans can access a ride to the VA from a central meeting point. Enrolled members of a federally recognized tribe have access to health care through Indian Health Services (IHS). The structure of IHS-funded clinics varies, and many provide transportation services to members in need who are not eligible for Medicaid or VTS.

Even with transportation benefits, Medicaid patients and paratransit riders experience many of the same barriers as non-NEMT and non-paratransit patients. Medicaid transportation does not include trips to the pharmacy or grocery store, for example, and some patients may not

have transportation options that match with their health care needs and schedule. Individuals needing paratransit service may need to access a destination outside of three-quarters of a mile from the fixed route or may need assistance getting out of their home or getting settled into their health care facility (transit providers can decide if they provided curb-to-curb or door-to-door service but generally do not cross the threshold of the door). If a veteran needs assistance in getting to the VTS meeting point, or, for example undergoes an outpatient surgery that prevents driving back home from the meeting point, then VTS will not meet his or her needs. Enrolled members of a federally recognized tribe may technically be able to access health care at an IHS-funded clinic, but their transportation options could range from assistance from a Community Health Representative (who may be unable to transport them when they need it), to tribal or other transit service, to Medicaid or VTS, to nothing at all. Because NEMT is a Medicaid benefit that is regulated by the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services (CMS), the ADA paratransit is regulated by FTA, the Veterans Transportation Program is managed by the VA, and tribal transportation funding is set aside and regulated through the federal transportation bill each service must adhere to different rules and regulations, and each service generates trip data.

While many patients travel to health care outside of NEMT, paratransit, veterans’ services, and tribal services, these four services are of particular interest when examining the return on investment of transportation access to health care. These four services are provided to some of the most medically vulnerable individuals, for whom access to transportation to health care can often mean the difference between managing an illness and developing multiple chronic conditions or ending up in the emergency room, between living independently and moving to assisted living, or worse.

Past studies have attached a financial cost to transportation barriers to health care, based primarily on missed appointments and on emergency department use and hospitalizations resulting from lack of primary and preventive care.2,3 These costs to the health care system and to patient health are predicted to increase as the U.S. population ages and as our chronic disease burden grows. Health care providers increasingly recognize that transportation is a significant barrier for many patients. Accordingly, we would expect an investment in transportation access to health care to result in benefits for the health care system and for patients. Because trans-

___________________

2 Wallace, R., Hughes-Cromwick, P., Mull, H. 2006. Cost-Effectiveness of Access to Nonemergency Medical Transportation: Comparison of Transportation and Health Care Costs and Benefits, Transportation Research Record:(1956). Pp. 86-93.

3 Cronin, J., Hagerich, J., Horton, J., and Hotaling, J. 2008. Florida Transportation Disadvantaged Programs: Return on Investment Study. Tallahassee: Florida State University College of Business.

portation and health care each manage a different transportation-related program, though, the financial benefits of one program investing in transportation may accrue to another program.

Transportation and health care providers operate under a different set of rules and regulations and have a different vocabulary to define their work and clients. These different vocabularies affect, too, what it means to examine the return on investment of providing transportation services to health and health-related destinations. How transportation and health care professionals define each concept—what is meant by health outcomes, health care savings, transportation, and return on investment—will have an impact on how data are collected and analyzed. Many interviewees discussed how to define return on investment relative to their specific program aims, citing health care savings, improvements in health outcomes for patients, and other societal and personal benefits that may be realized over a long term and/or otherwise difficult to measure or monetize. Many of the interviewees contacted for this report are engaged in some way with NEMT services. While the original contact list did not include a disproportionate number of NEMT-related contacts, interviewees often suggested additional contacts involved in NEMT. One reason may be the perception that NEMT programs:

- require specific data collection and reporting;

- are required to implement least-cost solutions; and

- have recognized gaps that may affect the cost of health care;

- making NEMT programs a likely starting point for many health care and transportation partnerships.

Health

The World Health Organization (WHO), in 1946, defined health as a “state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”4 This definition is widely accepted and has been in place for 70 years.

Moving from a definition of health focused on an individual to the health of populations, in 1988, the Institute of Medicine described public health as “what we as a society do collectively to assure the conditions in which people can be healthy.”5

As our understanding of the factors that influence health grows, medical health and public health professionals are recognizing their shared

___________________

4 See http://www.who.int/about/definition/en/print.html (accessed September 27, 2016).

5 See http://www.nap.edu/catalog/1091/the-future-of-public-health (accessed September 27, 2016).

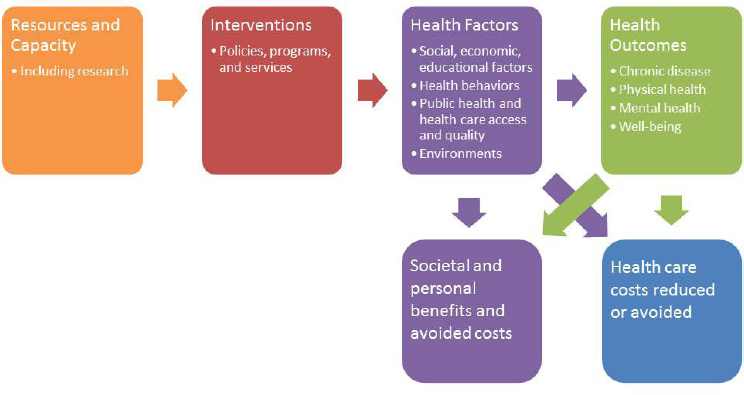

roles in improving patient outcomes. Public health logic models attempt to capture the relationship among resources, programs and policies, health factors, and health outcomes (see Figure C-2 for a logic model for transportation access to health care). Resources and understanding help drive interventions, in turn changing health conditions that impact health outcomes. Improvements in health outcomes and improvements in some health conditions may result in reductions in health care costs. In addition, both health conditions and health outcomes may result in societal and personal benefits and avoided costs that may never be directly reflected in health care costs.

For this environmental scan, the interventions we focused on are transportation policies, programs, and services to improve access to health care and health-related goods and services. Outside of the context of this environmental scan, interventions could include anything that may result in improved health factors—from violence prevention and immunization programs to building more sidewalks or increasing affordable housing supply. This wide range of possible interventions reflects the wide range of health factors that determine individual (along with population) well-being.

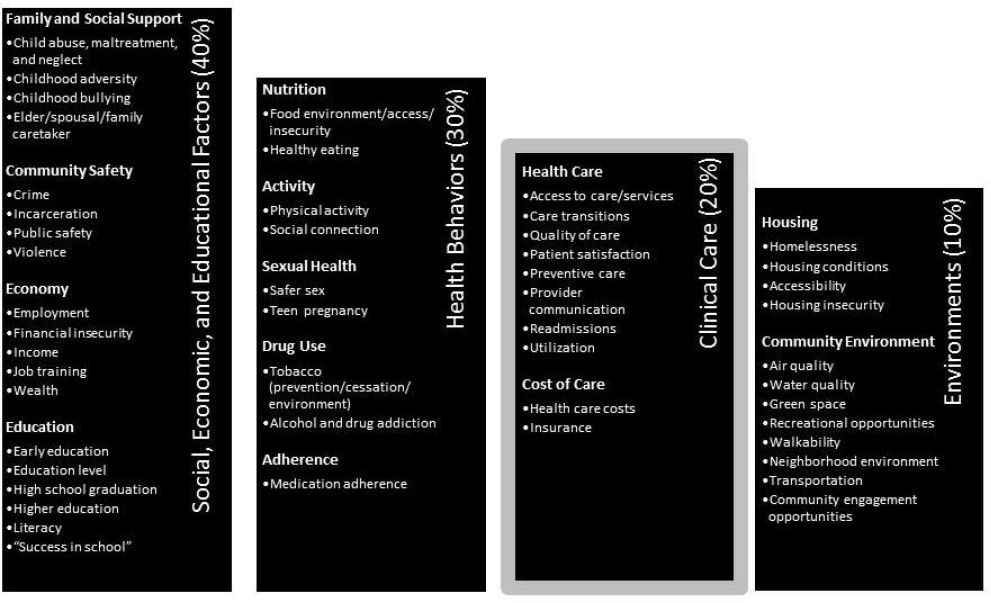

You may notice in Figure C-3 that another important health factor—genetics and biology—is not included in this model. Because the model (and this scan) focuses on the impacts of policies and programs, genetics and biology is not included. Also notice that clinical care is shown as being

responsible for about 20 percent of the impact that policies and programs have on health outcomes. While this factor includes “cost of care,” with respect to individual health outcomes, “cost of care” here means cost to the patient. However, in considering cost savings to health care providers or insurers, factors included under “clinical care” are relevant. Figure C-3 is not comprehensive; instead, it is focused on factors most relevant to transportation and health care partnerships.

This environmental scan did not include transportation programs solely designed for social and recreational purposes, though a growing body of research indicates that these trips are important for maintaining health and some interviewees, especially those working in rural areas, mentioned isolation as an important health factor. Consider again the WHO definition of health provided earlier: “state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” A recent report from Martha McClintock and colleagues for the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America indicates, “there has been little rigorous scientific attempt to use [the WHO definition]

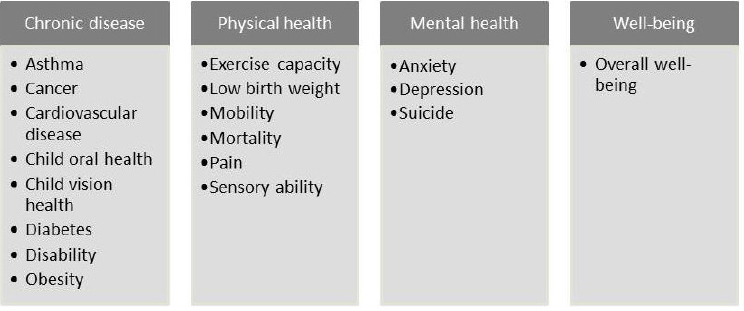

to measure and assess population health. Instead, the dominant model of health is a disease-centered Medical Model, which actively ignores many relevant domains.”6 Using medical, psychological, and health data from the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project, McClintock and colleagues found that “specific medical diagnoses (cancer and hypertension) and health behaviors (smoking) are far less important than mental health (loneliness), sensory function (hearing), mobility, and bone fractures in defining vulnerable health classes” for older adults. Figure C-4 shows some the main health outcomes impacted by transportation access to health care. This list reflects outcomes discussed by interviewees as well as outcomes suggested by McClintock’s work and a national health improvement initiative.7

Health care and transportation partnerships explored through this environmental scan do not directly measure the results of transportation investments in terms of improved health outcomes. Instead, measurements are often focused on utilization of primary care, emergency room utilization, hospitalization, transportation trips provided, and other data directly related to the provision of transportation and care. Although health care providers may have data on patient health outcomes, interviewees noted the difficulty of understanding the impact of transportation on access to care and the resulting impact of care on health outcomes. Interviewees expressed

___________________

6 See http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2016/05/10/1514968113.full.pdf (accessed September 27, 2016).

7 Adapted from 100 Million Healthier Lives Measurement System: Progress to Date (http://www.100mlives.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/IHI_100MHL_Metrics_SpringGathering_ONLINE.pdf [accessed September 27, 2016]) and McClintock et al., Empirical redefinition of comprehensive health and well-being in the older adults of the United States (http://www.pnas.org/content/113/22/E3071.full.pdf [accessed September 27, 2016]).

a desire to better understand the connections among transportation access, care access, and health outcomes experienced by clients.

Transportation

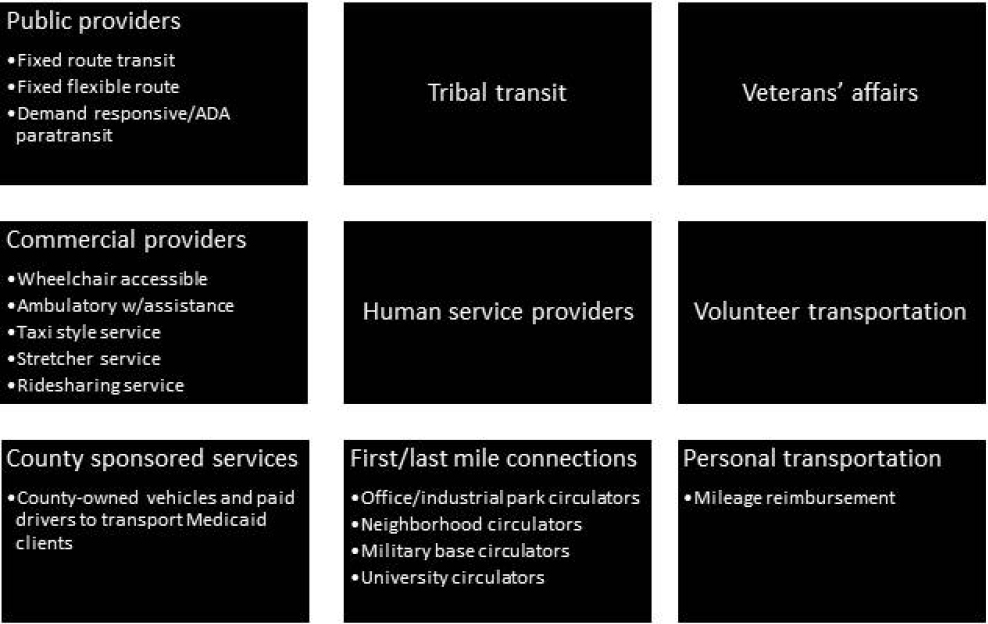

Transportation encompasses a broad range of infrastructure, services, policies, and programs—from walking on city sidewalks with curb cuts that accommodate mobility devices to trains, airplanes, trucks, and barges that carry freight across the land, air, and sea. For the purposes of this scan, we focused on transportation providers, services, or programs that either primarily transport people to health care or for which access to health care or health-related goods and services is an important component. To more easily consider available data sources and possible partnerships with health care, it may be helpful to categorize transportation on a continuum of modes of transportation and the various entities that plan, design, operate, and maintain these various modes. Figure C-5 below presents a collection of entities involved in various elements of the transportation continuum. Each of these is also supported by a network of roads, sidewalks, and paths that are developed and maintained by a combination of entities ranging from state and local governments to private developers.8

Transportation programs included in this scan focused most often on Medicaid clients accessing Medicaid-covered health services. Other populations often discussed included dialysis patients, veterans, people experiencing multiple chronic conditions, pregnant women, children, individuals accessing drug treatment programs, older adults, and people living in rural areas. Several interviewees discussed the importance of transportation in alleviating social isolation and noted how difficult it can be for many clients to have access to transportation to get out into their community outside of medical trips.

Return on Investment

Return on investment (ROI) is a kind of cost–benefit analysis traditionally measuring financial returns (or gains) compared to resources invested. For example, ROI has been used to determine the effectiveness of research and development or marketing efforts for businesses. More recently ROI has been adapted to examine social and environmental impacts through Social Return on Investment. For the purposes of this scan, we began by thinking of investments in terms of (funding for) transportation access to

___________________

8 Revised from FLPPS Transportation Committee Executive Summary, personal communication. (Committee information can be found at: https://flpps.org/Workstreams/Transportation, accessed October 25, 2016.)

NOTE: ADA = Americans with Disabilities Act.

health care and returns in terms of health care savings or avoided health care costs. We were also interested in efforts to track changes in health outcomes related to transportation investments.

One of the first steps in determining ROI in any context is understanding the outputs and how those outputs translate into returns. For example, transportation providers typically report on:

- fare revenue

- passenger trips

- project revenue miles

- deadhead miles9

- total project miles

- vehicle service hours

- volunteers

- vehicles

- incidents

- injuries

- fatalities

___________________

9 The miles a vehicle travels when out of revenue service.

These outputs are helpful to transportation in measuring a journey, but alone they are not sufficient to understand the full impact of transportation, or what happens after the journey.

For this scan, we were interested in learning about partnerships to connect these outputs to returns through reductions in health care costs. Unfortunately, several challenges emerged through the interviews:

- such data are not readily available from all transportation providers;

- existing data are insufficient to account for important context, such as the population density of the area served; and

- even if a health care partner can attribute health care savings to a trip provided (for example, by using an estimate for missed appointments), it can be challenging to allocate the right proportion of the relevant transportation metric to that trip.

Similar challenges exist on the health care side of the equation. Interviewees most often mentioned staff capacity and technology as the primary barriers to solving the first two challenges. To address the third challenge, one strategy often used in ROI analysis in other sectors is cost allocation, which would allow transportation providers to better understand the cost of providing each individual trip. While nearly every interviewee recognized some benefit to understanding the monetary benefits to health or health care of investing in transportation access, few programs were able to measure this directly. Even without this information, though, several transportation and health care partnerships are moving forward with a shared understanding that monetary benefits will emerge.

INTERVIEW BACKGROUND

Nearly 70 individuals were interviewed for this environmental scan. The interviewee selection is not representative of all of the relevant expertise on this topic. Interviewees represent a diversity of organizations and roles within those organizations—from federal agencies to local providers and community-based organizations, from individuals who distribute funding to those who managed programs and work with individual patients or clients. For a list of individuals interviewed, please see p. 160. Throughout the scan, direct quotes from interviewees will be used as examples of the major themes. In order to protect privacy and to encourage honest and candid information sharing, quotes will not be attributed to a specific individual. Instead, quotes will be followed by the sector in which the individual works:

- brokerage

- consulting/technical assistance

- consumer/consumer advocacy

- foundation/funding

- health services

- human services

- research/academia

- transportation services

- tribal transport/health care

- veterans’ services

Interviewees were asked about health and transportation partnerships that they knew of or worked within; business models that supported those partnerships; and the data collected, analyzed, and shared through those partnerships. Interviews were conducted primarily by phone and lasted 15–60 minutes. Interviewees were asked to suggest other potential interviewees as well.

Overall, among interviewees there was an appetite for better understanding the data and evaluation measures being used or under consideration in other areas—whether those areas are disciplines, geographic areas, or specific programs. There was an accompanying sense of trepidation about the limitations of examining the costs and benefits of transportation investments in relation to health care.

Interviewees expressed gratitude to FTA for funding this workshop and the other related efforts examining the intersections between transportation and health care, and several suggested areas where FTA and other federal agencies could support local efforts to coordinate and improve service provision.

SUMMARY OF THEMES

Across sectors and other variables like geography and client demographics, interviewees shared many of the same challenges and potential solutions. Overall, the most significant challenges interviewees face in creating health and transportation partnerships and measuring return on investment fall into seven categories (not listed in order of importance):

- Defining return on investment

- Funding and basic infrastructure

- Missing information and data

- Technology

- Geography

- NEMT destination and service gaps

- Cross-sector collaboration

Within each of these themes, sub-themes emerged, which are highlighted in each theme’s section.

Solutions and opportunities emphasized by interviewees fell into eight categories (also not in order of importance):

- Grants

- Shared learning

- Start small and go slow

- Let patients tell the story

- Take the care to the patients

- Customer experience

- Sharing resources, increasing revenue

- Sharing data, analyzing solutions

Fewer sub-themes emerged during discussions about solutions and opportunities.

INTERVIEW THEMES: CHALLENGES

Defining Return on Investment

Interviewees, identified below only by their sector, discussed the concept of return on investment from many perspectives, citing challenges and opportunities for how to explore this topic in the future. Major concerns included

Value or Return on Investment Outside of Health Care Costs

Interviewees agreed across the board that investments in transportation are critically important to supporting access to health care, but they did not all agree that improving transportation access to health care would necessarily result in reduced health care costs.

“We want to comment on the assumption about reducing the health care cost. Our position has always been that these are areas that are significantly underserved. . . . You’re introducing more patients, more frequent patients—could lead to more than just screenings and regular doctor appointment. It could lead to specialty visits.” –Transportation services

“This whole notion that we’re going to reduce the transportation costs if we work more collaboratively—I don’t agree with that. We’re very efficient.” –Transportation services

Interviewees suggested that between existing patients accessing more care and new patients beginning to access care, health care costs may increase, at least in the short term (see time scale comments below) and maybe for the long term as well.

“This is like a sieve—you create a little space and there’s lots more need. No matter what we’re doing, the more access we provide, the higher the cost will be, because we’re not providing for all of those needs now.” –Transportation services

“You’re getting people access to surgeries and other care they couldn’t get before. So the trade-off is that, for us, we see hospitalizations go up, because we are getting people access to care. But they need that care.” –Health services

Some interviewees suggested that measuring benefits in monetary terms obscures the real measure of success—improved access to care and patient well-being—and may not reflect desirable outcomes achieved.

“If your investment is in health outcomes and not profit, then why are we even talking about this? [Patient’s] life improved, quality of life improved. So why are we talking about it as only monetary? Investing in patients is good in and of itself.” –Transportation services

“We’re not trying to keep people from health care, so that’s not really the cost we want to look at. Are we adjusting medication or treating someone after a stroke? Is it making a difference for you, individual person who received a ride? Transportation providers—are you giving more rides because the system is more efficient? Health care providers—are you noticing fewer no-shows?” –Human services

“We do show that they got care they wouldn’t have otherwise gotten. We worry about the people who never get connected—at homeless shelters, etc. They’re not even showing up in the health care system yet at all, and maybe we can keep them out of the ER?” –Health services

The Time Scale Over Which We Measure

Many interviewees suggested that, while health care costs may be reduced as a result of better transportation access to care, these benefits might not accrue in the short term or even the medium term. Interviewees

suggested several ways that high care costs could be reduced with increased transportation access to primary care, from preventing emergency room visits to increasing the time a person can stay in his or her own home.

“Even though we’re always concerned about the trip costs, at the same time, we’re trying not let lack of transportation become a barrier to successful treatment. Often [patients] will come in in a very vulnerable state. It takes a while before they have success with their behavior changes . . . and we can start getting them to drive again or figure out other transportation. Sometimes that takes time, and it’s worth the higher cost investment to get them to that point.” –Brokerage

“It’s like everything in life—you have to put in up front to get a return on the back. What we do costs more up front. Up front that first year or two out of the facility costs more than being in, but after that, the costs fall off greatly once a person is established at home. We talk all of the time about how much cheaper it is for an individual with a disability to live in the community than in a facility, but it costs more to actually get them there.” –Health services

“One of the things that we really believe, is that what we do supports people living in place, decreases isolation, so they’re less likely to go to an assisted living facility.” –Transportation services

Return on Investment for Whom

Interviewees described many benefits of improved transportation access to health care and health-related destinations that will not necessarily be reflected in health care costs. This topic generated some of the richest feedback from interviewees, providing ideas for future study.

For the Patient

“Our program encourages states to look at inclusion post-discharge. Rather than just moving somebody, and then you’re on your own. . . . We encourage our grantees to tell us how they’re going to encourage people to get involved—something to get them out of the house and be part of the new community” –Health services

“Indirect route and the long wait times were concerns [for patients], because they have to dialyse for so much of their life already, having to add an hour or two increases the time that they’re all about dialyses and not about their life. . . . ‘I need to go home, take a nap, so when my kids get home I can make dinner and be part of their lives.’ Doesn’t have a cost that can be quantified with money.” –Transportation services

For Caregivers and Family

“[There was a] gentleman who needed to go to bariatric treatments three times a week. His wife had a disability, and he took care of her. If he hadn’t gotten reliable transportation, his wife would have had to go into assisted living. Who knows what would have happen to his wife if he hadn’t been able to get that transportation.” –Human services

“[Could we quantify] family costs, such as costs saved because family members who are caregivers can return to work and/or engage in family activities because their role as caregiver diminishes as their loved one gets well?” –Human services

“Caregivers often quite frequently die before the people they’re caring for; so the ripples [of giving them a break from transportation] are spreading throughout the community and is ultimately just a win for everybody.” –Transportation services

For the Community

“It would be great to quantify: economic contribution of individuals because they can get to work; increases on workforce participation for those individuals who coordinate transportation service or provide the rides directly; decrease in lost productivity costs for employers—reduction in need to hire temporary employees; increased production or service; decreased health insurance costs; community costs—costs on community integration, participation in religious and civic organizations. People who are healthy can spend money in the community, participate in community recreation and entertainment events, they can vote, they can attend events (that might have entry fees), etc. Could these costs be captured?” –Human services

“[Patients using ambulance for nonemergency transportation] may put other people at risk, too. If they’re bringing people to nonemergent medical appointments, that keeps them from being able to provide emergency care.” –Research/academia

“If we have patients who are abusing drugs, they’re going to have myriad health conditions. Their children are going to have health issues, domestic violence issues, going to be in jail all of the time—it leads to societal issues as well as health issues” –Health services

Funding and Basic Infrastructure

Interviewees consistently talked about the need for more funding to effectively meet the needs of clients and patients. In response to having too few resources, interviewees emphasized two major themes—going slow and

starting small—that will be addressed in the “Solutions and Opportunities” section. In addition to the nearly unanimous call for more funding generally, individuals working with tribal transit and tribal health care highlighted the need for basic infrastructure on tribal lands.

“When [other provider] is talking about the sheer danger of being on the roads, it’s very real. The only road into their community is a 36 mile dirt road. To have a school bus driving on that road is scary. Anyone who needs higher medical care than their clinic can provide [to get there] is scary. Getting food in—18 wheelers on that road—is scary.” –Tribal transport/health care

“Sometimes [water] trucks crash, or there’s a flash flood and folks can’t get through. EMS services—sometimes the ambulance can’t even make it over their roads.” –Tribal transport/health care

“With respect to transportation for Indian country, to be quite honest, it’s not just access to the automobile that would get them there, it’s about the roads and whether they’re passable—whether they can even get there, and if they’d want to risk getting on those roads.” –Tribal transport/health care

Missing Information and Data

Another significant theme across interviewees was related to whether and how relevant questions about access were being asked at all levels of service. Several interviewees working in health care and transportation partnership noted that their work was catalyzed or informed by community needs assessments.10 Sometimes these needs assessments included questions about transportation, and other times participants brought it up on their own. Others noted that health care providers may not have information about a patient’s transportation barriers or if an appointment was missed due to transportation. For tribal transportation, data concerns were primarily focused on crash and other safety data and on GIS data.

Asking the Right Questions

“Sometimes the patient makes us aware of transportation issue, but other times they won’t voice that need if they’re not asked.” –Health services

___________________

10 Such assessments are an Internal Revenue Service requirement for not-for-profit hospitals and health systems, and are also required of public health agencies by the state or for the purpose of obtaining public health accreditation (see, for example, https://www.nlm.nih.gov/hsrinfo/community_benefit.html and http://www.phaboard.org/accreditation-overview/getting-started [accessed September 27, 2016]).

“What we found when we asked initially, a lot of them didn’t even know why people weren’t showing up for their appointments.” –Human services

“We’ve learned many things such as the anxiety that people have, of using public transportation, for behavioral health” –Transportation services

“We already had a one-call center. What we didn’t have was the mechanism to identify the at-risk patients to address re-hospitalizations.” –Health services

“Regional hospital did the community health assessment but didn’t ask about transportation. People would hand write in the margin—access, language barriers.” –Transportation services

“You call to make a doctor’s appointment. The very first question is ‘What insurance do you have?’ We want the second to be ‘What kind of transportation do you have?’” –Consumer/consumer advocacy

“If you use a lot of transportation (not counting dialysis), what are people actually doing when they’re using a large amount of transportation? Does that mean anything or not?” –Transportation services

“Ask outreach programs what they think their needs are. Our sense is that with health center data there’s a bias, based on patients that are already walking into the health center doors. For folks not accessing the health care system, the only folks who might have a sense of those barriers are outreach workers. They directly interact or observe some of the groups that don’t go to the health centers.” –Consulting/technical assistance

Some interviewees noted that it is insufficient to just ask whether or not a patient has transportation; the accessibility of that transportation in terms of culture and timing might have an impact on health care accessibility as well.

“How well are health centers asking that question? They’re not always realizing what options are out there. Need the partners to ask the question in a culturally competent way, in a way that really collects information that we’re looking for over time.” –Health services

“The need for same day service is huge—now they can go to the doctor if the doctor will accept them.” –Transportation services

“We are a city of bridges and tunnels and rivers. It’s no big deal to cross two bridges and go through a tunnel, but for some people it is [a big deal]. You need to get a handle on the culture of a place as well.” –Consumer/consumer advocacy

“Moms who are at risk of going pre-term, they have to get a progesterone shot to help them get along as far as possible. They can only get it from a compounding pharmacy—only three of them in the region, most in the suburbs. It’s a weekly shot. You’re only going to pay to get to the doctor; it’s important, but the shot is just as important in getting her to full term. If [her] level of comfort to get on the bus (if she can afford it) to go up to this working class pharmacy to get this shot—it’s just not going to happen. Gets into race and affordability. . . .” – Transportation services

Impacts of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act

One challenge to measuring return on investment that many interviewees noted is the impact of health care transformation. With an increase in the number of people with private insurance and eligible (in many states) for Medicaid, costs are likely to go up in the short term, making it difficult to evaluate a return on investment. New patients may require education about their benefit and other service to help them fully access care, and these costs may impact a provider’s ability to evaluate a return on investment as well.

“[Measuring is] further complicated by the ACA and whether or not the state expanded its Medicaid program. There may be an increase in cost—is that a function of delivery of transportation or simply more individuals eligible. What if medical services aren’t available [nearby], and transportation costs increase for that reason?” –Research/academia

“Ramping up for health care coverage, but for the groups most in need, having coverage was not the same as having access; [there’s] distrust and fear in the system (based on immigration, race) and transportation barriers.” –Consulting/technical assistance

“With the ACA and the expansion, we have this population that came on to a plan. A lot have never had insurance and need education about benefits, how to utilize insurance.” –Health services

Same-Sector Information Gaps

Interviewees discussed data-sharing challenges not just between transportation and health care but within each sector as well.

“Information on the transportation side of trips—some of that data is out there, we don’t necessarily have access to it. On the medical side, we can see outcomes of people. What’s missing is how to connect a person’s health to their transportation, so that when transport is identified as a barrier or

need, the health care center can make sure they’re providing the right kind of transportation to that care.”

“There’s a Medicaid broker who helped try to arrange transport. [Patient] had a behavioral appointment that Medicaid would cover. Their doctor said [patient] can take public transit. Their counselor said [patient] needs taxi service because of anxiety. The broker sides with the physician (or the cheaper form of transportation). Sure enough, [patient] doesn’t get to their appointment.” –Health services

“Trying to figure out how much money it costs for a pre-term birth, that info is not public. Negotiated rates with the insurance companies—[health care providers] won’t give that; but also, that’s not necessarily the costs. We’re only including the hospital stay [in our return on investment evaluation], but you get billed by hospital, doctor, everyone who worked on you. [We] couldn’t keep track of everything—we’d have to ask each of the individuals. So we need to have a relationship with the insurance companies to get them to tell us what’s being saved.” –Foundation/funding

HIPAA

The two biggest challenges interviewees mentioned around data was related to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Many interviewees have decided to forgo working through processes related to HIPAA and instead use data related to trips or other non-health proxy data.

“The thing about HIPAA—in small towns, everybody knows who you are if you dig into it enough. [Maybe it should be] us feeding the hospital the transit data and them doing the analysis without talking about the people—just a higher-level aggregate.” –Consulting/technical assistance

“If they had told us, ‘Here are our top ten ER utilizers, go out and serve them. . .,’ but none of our partners would share anything meaningful with us because of HIPAA.” –Transportation services

Data on Tribal Lands

Interviewees working in tribal transportation and health care discussed the challenges of funding and operating transportation infrastructure and services without basic data that other sectors often take for granted—crash statistics and GIS in particular.

“When the state divvies up dollars, a lot of times they will exclude tribes, not intentionally, for a couple of reasons: they really don’t think about it,

and tribes aren’t sharing their crash data or don’t even have crash data. So even when the tribes do ask for money to improve the roads, the state doesn’t see the data to justify why they need the money to improve the roads.” –Tribal transport/health care

Technology

Technology was cited as a barrier to partnership and a tool to improve partnership and data sharing. In particular, interviewees noted the need for data standards and flexible and open software to support for partnerships. Even if an agency is up-to-date technologically, clients may not be able to access the technology due to a lack of awareness or because of their own technological limitations.

Need for Standardized Data and Open Technology

“Modern data standards, well-documented code—allows us to plug and play different solutions as needed. Everything changes so fast, and we need to be ready to meet those needs as they come. Doesn’t necessarily mean it has to be open source, but it does have to be developed in a way that is flexible enough to tap into new technology and data sources.” –Consulting/technical assistance

“A lot of it goes back to the transit program having the correct technology to dispatch their drivers on time and to the right location.” –Tribal transport/health care

“One of the biggest struggles working with the public transit providers and using fixed-route service is a lot of them don’t have OS data or GTFS files. [There’s] no one-stop shop nationwide so I can appropriately identify the trips and geocode them. Having access to OS GTFS data could make all of the difference in the world in regard to NEMT using the fixed route services. We would be open as a brokerage to exploring the option of helping these agencies create this data.” –Brokerage

“You get all of these little proprietary systems. How do you collect data when they don’t connect with each other? The FTA or some federal agency [could take] the lead and make open source platforms, standards.” –Transportation services

Client-Side Technology Barriers

“[We’re doing] one year of planning to make sure our technology will serve the needs of the individuals in the center for independent living—-

individuals who are unable to see or hear; will it work with the reader devices, etc.” –Brokerage

Tracking Trips

The difficulty of tracking transit trips emerged as a concern primarily related to NEMT but also in general for considering return on investment. The potential of electronic fare to enhance trip tracking was discussed by several interviewees.

“Public transit agencies (don’t know if they’re carrying a veteran or a NEMT trip).” –Research/academia

“One thing we found, especially in the public transit system, it can be difficult to track who is riding and what kinds of needs they have. If you don’t have a card that identifies who the riders are, then the systems are not able to identify with great accuracy. They can probably make decent estimates of what riders fall into what categories, but if you’re looking at a short period of time at increasing ridership, that can be challenging.” –Consulting/technical assistance

Geography

Challenges related to density of population and different kinds of service boundaries were a common theme among interviewees.

Rural Challenges

Interviewees noted that transportation and health care needs and appropriate measures of success are different for rural areas, compared to urban and suburban areas. Interviewees also noted that much of the transportation need in rural areas is related to health care.

“Transportation for us is really a problem in rural areas. When people want to transition back to their home on a farm, the state has to give us a 24 hour back-up plan. So states are slow to move people back to rural areas; [they do] not want them to move from a facility back into seclusion.” –Health services

“There are very different issues in the rural and non-rural areas. The metrics around transportation needs some component to take those into account. How are you using resources efficiently if there are only seven people per square mile? That’s something we’re finding. We have the numbers for each site; when we look at number of rides, distance of trips—the more rural the site, the less efficient the transportation is. Unless that is

pointed out to leadership, they just think that the program isn’t functioning well.” –Veterans services

“They had to start with criteria that said less than seven people per square mile. What about the rural parts of neighboring counties, say three people per square mile, but the county average brings it up? We’ve driving right by people who should have access.” –Veterans services

Jurisdictional and Service Boundaries

While barriers in each state differ, interviewees across the board experienced challenges crossing service or political borders. Interviewees expressed frustration at not always knowing who was imposing the boundaries and what could be done to better integrate neighboring systems.

“All of the sudden you have this brokerage in [Town A] trying to get someone to [Town B] and back. How do you even out the cost? Basically [you] need to have agreement between each of the transportation providers.” –Consulting/technical assistance

“You have to be certified by each of the providers, pay whatever rate each charges. That’s a huge barrier as far as independence. You can only go as far as my service goes—beyond that you have to work with another provider.” –Health services

“We had to get federal motor carrier authority to be able to take folks to the clinic in [other state]. We were the first transit agency to go through that process. No one really knew how to do it, and [we] had to get transferred so many times, because they don’t know their own rules. It took us a year.” –Transportation services

“That whole issue of not being able to cross lines or borders without those agreements—I understand that intellectually. But is there something they can do to make that easier? It’s ridiculous. I can get my patient to the border, but then I have 2 miles to go, and I have to get someone from another county. Is it a statutory requirement? A funding requirement? If you’re going to have regional health care, there’s got to be some way to make this a little easier to do.” –Health services

“Health care did not have the capacity to take people to regional care. We need to cross 1, 2, or 3 municipal boundaries, and the original model was designed for local rides on a recurring basis.” –Human services

NEMT Destination and Service Gaps

These issues were raised generally and in relation to Medicaid, Medicare, and VA transportation. Interviewees described several health-supportive destinations that they considered to be key factors in improving health outcomes, including pharmacies, group homes, support groups, grocery stores, assessment appointments, and benefit qualification meetings. Some interviewees also discussed difficulties arising from children and caretakers not being able to ride along with patients.

“The big one that we always hear is pharmacy; there are tricks to get your prescriptions on your way home from the doctor.” –Health services

“Even groceries—some [patients] can get them delivered, but many do not have this option. You’re at a severe disadvantage to maintaining yourself at home if you can’t even get food.” –Research/academia

“You have to have a face-to-face with a physician to say you need home services—well that requires transportation to get there in the first place!” –Research/academia

“Transportation is an issue, too, at the point of preparing to transition. We have to get people to Social Security offices, get them to go and view places they can live. If they’re not part of the paratransit system or any number of [other barriers]—if they can’t easily get to and from where they need to go to make the transition process happen, it makes things more difficult.” –Health services

“We started a rides to grocery program. We had mom and pop stores closing and nowhere to buy groceries. Rides to groceries was designed to provide options and hope for people. Little were we aware of the linkage between fresh fruits and veggies and health care. We have many partners in that program.” –Transportation services

“A lot of nonprofits have rules about not going to group homes, but a lot of group homes don’t have vehicles.” –Brokerage

“Even one of our local assisted living programs doesn’t have an ADA vehicle. They won’t buy one—we’ve tried to sell them one.” –Transportation services

“A lot of these patients wouldn’t have had any appointment for behavioral health [without our program] because Medicaid doesn’t cover the initial assessment.” –Human services

“The thing I hear the most is we have free Medicaid transportation, but I can’t bring my kid. I can’t get a babysitter for them.” –Foundation/funding

Cross-Sector Collaboration

Cross-Sector Knowledge

Interviewees described hurdles to collaboration, including confusion around language, funding sources, how different programs operate, how to connect with the right individuals in other sectors, and what programs might be appropriate to partner with. These same concerns were echoed during the Improving Healthcare Outcomes: The Mobility Management Connection symposium during the 2016 Community Transportation Association of America (CTAA) expo in Portland, Oregon. The following quotes are from interviewees, not CTAA participants.

“It would be ideal if CMS and FTA could get together and put together a common language or corresponding language.” –Brokerage

“If the state DOTs could have sort of ‘go-to people’ lists available for the transit agencies that are out there in their respective states. Even within the agencies that should know their own rules, there’s a lot of misinformation out there.” –Transportation services

Different Motivations and Measures of Success

Several interviewees suggested that diverging missions or measures of success create significant barriers to effective partnerships between health care and transportation.

“We find that both public transit and Medicaid NEMT have a similar goal—they want to provide individuals, especially those without other options, access to health care. And there’s an expectation that it will improve outcomes. Beyond that, they don’t have many additional goals or objectives in common, and in fact they sometimes diverge.” –Research/academia

“Health care operators are always going for the least cost, trying to drive down the cost as much as they can—including transportation. Or, there are some saying ‘what if we provide all these access and support services so people can be healthier? Will that reduce our costs?’ CMS is driving both of these models at the same time.” –Consulting/technical assistance

“The two professions come at this from a very different perspective. The public transit arena would like to think that through coordination and shared trips that they’re capable of providing the lowest cost, most effec-

tive transportation. But from Medicaid, the transit agency is not always lowest cost. So you see the evolution being more and more brokered through a private broker and capitated payments, so there’s not a link to the trip provided and the payment made. And the private broker is looking to make the trip at the lowest cost, maintaining their contract, and making a profit margin. Public transit agencies with fleet replacement, advanced vehicles, technology, etc.—not necessarily seen as valuable to the Medicaid transport folks. Public transit seeks to recover its operating costs, but the Medicaid brokerage is really just looking for the cheapest; [there is] not consistency about those objectives and how to measure them.” –Research/academia

“There’s a contradiction in the NEMT language. It encourages demand response trips as a last response. They encourage people to use public transportation to the maximum extent possible, but if that happens, there’s no way to track that trip. Maybe you provide a fare ticket or a fare card; short of a smart card, you can’t track it. But that’s the lowest cost for everybody. NEMT—they encourage it, it’s in the language, but there’s no effort to require that or to document, to evaluate an individual or their trip and then send them that way. You’d think brokers would encourage that since it lowers their cost, but they can’t track the encounters, so that’s counter to their mandate to track data.” –Research/academia

“The people that are most interested are the payers—the insurance and the managed care folks; not really the health care providers.” –Transportation services

“Until transportation becomes an incentive measure, then we wouldn’t have a real frequent process of looking at that. We do look at people who are the most fragile who go to the ER a lot or access care a lot. We do reach out to them to see what their needs are—that’s one thing [readmission] that is an incentive measure, and transportation is part of that.” –Health services

“Transit people have [an] assumption that more access and more rides are better. People paying for health care (mainly Medicaid, since they pay for transportation) embrace attitudes of insurance company—‘the less we have to pay, the better, so more transportation is the opposite of better.’” –Transportation services

One issue that interviewees mentioned repeatedly was that a strong emphasis on fraud prevention on the health care side might be hindering more effective partnerships between health care and transportation providers. The challenge seems to be ensuring proper use of funds and services while maximizing benefits to patients.

“Medicaid funds have to be used for a beneficiary who needs to get to an approved medical trip and no other purpose. They can’t be on a bus with a veteran or someone else. It creates a perverse incentive for some successful programs to not chat with researchers about what is actually working and successful if it fits into a grey area. If you’re trying to do something innovative that just works for your patients, not trying to break federal grant rules, you may want to avoid having to ask forgiveness. They may not even know they’re in violation.” –Research/academia

“In the VA, folks are very concrete. They’re worried that the veterans are just saying they needed [the transportation program] because they like the service.” –Veterans services

“Public transit is looking to provide any users transportation for any trip purpose in the most cost-effective manner possible. NEMT is looking to get Medicaid eligible people to Medicaid eligible appoints for the cheapest cost. [Medicaid is] really looking to prevent fraud and abuse—including using transportation for any other trip purpose, even shopping. Doing so, even as trip-chaining, would be considered fraud or abuse.” –Research/academia

Coordination

Interviewees noted that coordination improves as it is mandated, and several commented on the importance of coordination at the federal level.

“Coordination mandates need to be happening on both sides. Right now, that mandate is on the DOT side from the FAST Act, but it needs to be mandated for other folks spending money on transportation and flow down to the states and regional coordination. Medicaid sends the money to the states, and the states have great latitude to spend this money. They have no ultimate obligation back to adhere to coordination or the intent to work with local public transit agencies to work effectively with resources.” –Research/academia

“When brokerages were just getting established [health services] came out very strongly that brokerages were creating a siloed system—they already had a state coordinating council. [Recently] they said that brokers are helping facilitate, but it’s due to some of the state requirements for coordination.” –Research/academia

“Over 80 programs provide funding for transportation disadvantaged populations, around 40 or so federal programs that provide [NEMT] funding. [Where is] data on the programs, on the number of people they provide services to, which grantees, how much funding is being used.” –Research/academia

“This is going to sound way out there. It just seems to me we have so many rural veterans in this country, it would be nice if CMS could partner with the VA to leverage some of those transportation resources. They drive right by and even go through the same community.” –Research/academia

“My experience with Medicaid is that it’s one of the areas where it was hard for people to understand. [The Medicaid NEMT provider] can transport people to VA medical centers, and it’s a covered service from the perspective of transportation. From the visit side, there’s not encounter data—it’s not available. That does create some issues if you’re audited. But you’re helping a veteran get to the care that’s more appropriate and allowable. It creates a little discomfort.” –Health services

“[We’re] like 5-year-olds playing soccer—everyone storms around the soccer ball and are all trying to do the same thing, not aware of what other people are doing and when to pass the ball.” –Health services

Change Takes Time

“We’re learning we have to really start small. The willingness, for people to change and organizations to change—it’s really hard to do. The idea that we’d make suggestions and wave carrots and people would change isn’t really happening.” –Health services

“When you’re bringing worlds and disciplines and sectors together, it’s not the easiest natural place for people to go. Give adequate time and space to understand each other’s language, build trust; it takes time, intentionality, real management whether at the highest level or within community. Be mindful of the longevity of the effort, what it takes in terms of the active management could be easy to overlook if you’re just looking at it as part of the data and programmatic end.” –Foundation/funding

“It always takes more time to develop the connections than you can ever plan for. If you don’t take time to do that, you’re basically putting together a program. A program can never address a complicated social issue. Five years later, everybody’s going to look back and say, well that didn’t really work. You have to develop a lot of trust to be able to work together; it’s not for the faint of heart. We’ve certainly seen some people drop off who have no tolerance for that type of work. We would have just continued to meet and admire the problem from year to year and not changing it.” –Human services

“We’ve been working with [software company] for about 3 years to purchase our product for our call center, making significant customizations. After we began working with [Coordinated Care Organization], they required us to have a business associate agreement with any of our

contractors, especially if sharing data. It took us 18 months, but we finally got a signed business associate agreement with [software company].” –Brokerage

“I got all of the groups to come and meet and talk. ‘We’re in competition with each other for funding—your passengers aren’t going to ride in my vehicles.’ It’s changed so much since then, but it’s taken a lot, and some people are still not willing to look at new ideas.” –Brokerage

INTERVIEW THEMES: SOLUTIONS AND OPPORTUNITIES

Grants

Several interviewees viewed the Rides to Wellness and other grant opportunities as catalytic in the creation or progression of partnerships between transportation and health care.

“This opportunity came, a real reason to work with the transportation folks. We didn’t have them on our coalition. [Rides to Wellness] is what created that impetus.” –Foundation/funding

“These [projects] emerged from the conversations we had even prior to applying for the grant. After applying for the grant, were able to form partnership more coherently.” –Brokerage

Shared Learning

Interviewees relayed a need for more and better systems for sharing learning relevant to this topic. Several mentioned having met peers at conferences or learned about other projects through grantee meetings. Many interviewees suggested areas where it would be beneficial specifically to have more guidance from the federal agencies, including related to funding streams and associated rules and the Stark Law.

“[There is a] need for more knowledge management in this area—we have a tendency to have great ideas, implement them, someone comes in and tries to make it more ‘efficient’ and then basically blows it up.” –Consulting/technical assistance

“It’s now easy for us to look at these things, but prior to doing this work we wouldn’t have thought about it. And that’s how we can contribute—help folks to start seeing—‘Oh, my peer did that.’ Otherwise we get really dismissive. If people see organizations like theirs tackling these challenges—that’s the importance of the peer-to-peer learning groups.” –Consulting/technical assistance

“Brokerage [is] operating under ‘you have to be 18 to get your own approval to get transportation for health care, to get approved for health care.’ The law says as young as 12 you can receive health care without guardian permission.” –Health services

“[Health services] really hold their hat on this [Stark] law that prevents them from paying for transportation. We believe that’s just an interpretation.” –Transportation services

“They can ask for things in their states plan in the way they execute their Medicaid program, likely to be approved in an individual level. Just because someone doesn’t think the funds can be used that way, sometimes they can. How it plays out on the local level is completely locally driven.” –Research/academia

Start Small and Go Slow

By far the most commonly discussed theme across all interviewees was the amount of time that transportation and health partnerships and programs take to build. Interviewees suggested several different reasons for and benefits of going slow. Because the need for transportation to support health is so great, some programs suffer from trying to grow to quickly or setting out to solve too many issues at once. Several interviewees noted how difficult it can be for individuals and communities if a transportation program disappears or is scaled back.

“The goal is 1 year of planning to make sure our technology will serve the needs.” –Brokerage

“It was meant to be a small thing, and it grew too much. It turned into something bigger than we expected.” –Transportation services

“[We’re] definitely trying to control the growth, because we’re still learning and there’s a lot we don’t know. The bigger we get too soon, the capacity becomes an issue.” –Human services

“We are focused on a part of our state that by all indicators really needs help. It has been the beneficiary of a lot of programs saying ‘We’re coming in with the answer to your problems.’ [There was] not a lot of buy-in from the local folks. [Our] core element at this point is planning—not ready to run out and develop a service, say ‘Here is the answer.’ Lots of outreach is needed in this initial buy-in to avoid push back and avoid low utilization.” –Transportation services

“Without success, we won’t get the other folks to the table to support us. That’s why we are narrowly focused.” –Transportation services

“We had to keep scaling down this program, because the demand was so much greater than the money we had.” –Transportation services

“Those [Rides to Wellness] projects that focused on information and outreach actually seemed like they had a good first step to the future work they might be doing. Those that were trying to come up with new models of service coordination or service provision—some are going to work out, but it’s more aggressive and had more risks along the way. To try to change how to provide what we’re providing, this stuff takes time. A lot of times people are surprised by that.” –Transportation services

“For last 2 years, [we’ve been] laying foundation for starting the partnership with the transit agencies and reaching out to bring awareness to the benefits of partnering with the NEMT brokerages—for us, them, the members they serve.” –Brokerage

“We have always had an historic partnership with the [program]. It’s been the paratransit service’s largest customer for the last 25 years. I was in a meeting when we were faced with this issue. The design challenge email came through the next day, so we started working on it.” –Transportation services

“One thing that’s come out of this to me that’s been worth all of the time we put into it—we have built the greatest partnerships in this community to understand health care and how we can all work together.” –Transportation services

“We have access to our leaders; you can just pick up the phone. Maybe if you had asked me about that 5–6 years ago prior to [project], I might not have said that. Since we’ve gone through such a strong exercise of building the [project], it keeps the partnership going.” –Transportation services

“Make sure you know everything else that is going on in your community. You may be duplicating efforts, you may be so overwhelmed with demand that your great idea becomes more of a headache than anything else, and you’re still turning people away left and right. Know who you’re going to serve, who you could not service through the program. If you want to develop an effective program serving the population you want to serve—reach out to them and ask them what they need, what they’d like to see, what are the problems they’ve encountered, how can you ensure whatever gets built, provided, funded in the community addresses those needs.” –Consulting/technical assistance

Most interviewees expressed a need for more resources, but many also discussed the need to work with available resources—from funding to community assets—in the short term, while future financial funding is unknown or unstable. This theme is closely related to the next theme, because many interviewees viewed working with current assets as the most sustainable way to begin new partnerships or programs.

“What we see so often is that things develop quickly without a sustainability plan. How can we be sustainable as funding comes and goes, while we make something that’s reliable and a utility for people? Our users rely on us—we can’t just go away next year. Innovation is the hot thing, but what can we do to support, grow, and amplify the things that already exist.” –Consulting/technical assistance

“If someone would just give us a lot more money we could do this or that. But that’s not coming soon, so what are we prepared with right now with what we can provide? How can we do that most collaboratively with what we have right now? How can we best get the results we need with what we’ve got?” –Transportation services

“Some partnerships formed, a lot [are] in the beginning stages. We talk about fixed-route services first. That was the first piece, work with transit agencies all across the county, identify members who can use fixed route services and are within .75 miles of a stop.” –Brokerage

Let Patients Tell the Story

Several interviewees emphasized the importance of listening to patients’ stories and working with patients to help develop programs and resources. Some interviewees had been able to previously develop video or Photovoice11 projects and found them to be very valuable for both the patients to share their perspective and for the organizations to make progress in funding or otherwise supporting partnerships and programs.

“We talk internally about how important it is to talk about this from the perspective of the patients. The solutions are about people.” –Consulting/technical assistance

“If you’re talking to 20 providers, you should talk to 20 consumers.” –Consumer/consumer advocacy

___________________

11 A definition of the Photovoice process is available at http://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-ofcontents/assessment/assessing-community-needs-and-resources/photovoice/main (accessed on September 27, 2016).

“What needs to drive what we collect and track and use to make decisions is the relevance to the individual—to their needs and if those needs are being met. The person being served is at the center of how we’re collecting this data and how we’re using this data. Quantitative data isn’t enough—we need to know how their quality of life is being impacted.” –Transportation services

“We [dialysis patients] make a huge impact [talking to decision makers]. It’s not just a story for them—I’m real. It’s not ‘There’s 270,000 of us [dialysis patients].’ I try to put a face to it—we’re real.” –Consumer/consumer advocacy

Take the Care to the Patients

A few interviewees mentioned existing or planned mobile units to respond to transportation barriers. These existing and planned units have foci ranging from children’s health and adult primary care to behavioral health crises and hospital discharge follow-up. One interviewee recommended creating a mobile pharmacy.

“The plan once we get it up and running is to have a list of people who have been discharged from our hospital during the week, and [mobile unit] would go out within 2–3 days to visit them and make sure things are going well. They’re able to intervene within a limited scope to prevent readmission, funded through the cascade health alliance.” –Health services

“In the aftermath of CHIP passage, the period of time after the money had been given out, [there was a] lag in uptake in certain states. We put two mobile units in the deep South, heard from a lot of concerned folks—that while they were excited about the prospects of having kids enrolled, a lot of them were experiencing long-standing transportation barriers and rendered their newly gained insurance coverage not as useful as it should have been.” –Foundation/funding

Customer Experience

Customer service was a common theme among interviewees, with several noting the value of the extra training that public transit staff complete. In all regions, but especially in more rural areas, interviewees noted the benefit to clients of having regular drivers, volunteer or paid, with whom the patient develops a relationship.

“Working with insurance companies, drivers have HIPAA training—extends from the health insurance companies but is a different model. Cli-

ent base is vulnerable in some way, so the drivers need to be altruistically motivated, customer service based.” –Brokerage

“One plan originally didn’t offer public transit, and now it’s the highest utilized option. Members have been happy, complaints have gone down, and they’re saving money.” –Brokerage

“The small public transit in rural areas are people-focused and community-focused. From a brokerage perspective, it’s good to have people on the ground providing services for you.” –Transportation services

“The other element [to address] from a federal perspective—our customer is the same customer as a public transit customer. From Medicaid and FTA—anything we can do to make it easier to access those services is good. A lot of times we’re all serving the same customer, the payment and eligibly is different; are there ways to make that easier for the customer?” –Transportation services

“We’ll send as many trips as possible over to [public transit], and we get reduced complaints, better member service.” –Brokerage

Sharing Resources, Increasing Revenue

Although most interviewees described challenges in creating partnerships that involved cost sharing, several also shared examples of early partnerships that included in-kind donations of staff time and other resources. Cost allocation was suggested as one tool to help transportation and health care partnerships better understand inputs and outcomes to measure return on investment. Some transportation services staff discussed the revenue benefits of working more closely with health partners in terms of Medicaid transportation trips, too.

“One of the things I did at the brokerage was to try to support the public transit agencies to contract with us, keep them busy. The Medicaid transportation became an additional source of revenue that supplied match for the federal grants. I viewed that as being a win-win any time I could partner with those types of organizations.” –Transportation services

“We run the fixed-route bus service; also run the NEMT brokerage for the three counties—whatever is needed to get them to their health care appointments. That’s become a real big business for us dollar wise—bigger than general fund.” –Transportation services

“Program of all inclusive care for the elderly—we are the only type of transportation provider to provide this transportation service in the country. [The] operation is part of the local hospital. They pay the full cost of

the rides. Through the contract, we provide the vehicle, the driver, and an attendant on board, through your door to help and through your door to the health service. To the degree that the hospital is benefiting in their model and they utilize us, we can capture our full cost of providing that trip. It allows us to expand service without expanding the local subsidy.” –Transportation services

“Individual people who are eligible for these services—they know if they have an expectation for a demand response trip they can get it. Why bother with rail or bus in that case? In some environments, they know that the public transit agency is the option of choice, and they choose to just use fare—that means that the transit agencies doesn’t get the extra money they would from Medicaid (even though it saves Medicaid money from the demand response).” –Research/academia

“[We] launched a call center with a marketing team of board members and marketing director from [health services]—their phones, their computers, their office supplies—that’s their match. Expenses are my salary and the operating costs. [Health services] is doing all of my accounting and HR; I am a [health services] employee leased to [brokerage].” –Brokerage

“Our DOT public transit division is very supportive of the work we do. I’ve heard others talk about their 5310 money and how difficult it is to access it and use it—it’s often focused only on capital purchases. [The DOT public transit division has] receptiveness to maximize the use of federal dollars by leveraging state money and trying not to leave anything on the table. Regionally, having a transit agency willing to step outside of the box—using private, state, and federal programs—and having a transit authority that understands that public transit goes beyond a fixed-route system and beyond ADA is a benefit in our community.” –Transportation services

“The transit system has allowed the health workers to go on the bus with patients without charging us to get people used to it. Don’t know what that cost is to the transit agency.” –Health services

“First year of the [community health worker and transportation] program was funded by [CCO] as part of transformation money, now expired. Then the hospital took over the program—staff [is] hired by them and works for them.” –Health services

“[We have] two significant partnerships—both regional hospitals. As they looked at access, they saw loss of efficiency in the process by not having a centralized on-site presence to coordinate that effort. They both contract with [brokerage] and pay for a staff person to coordinate transportation; large part is Medicaid transportation, but it does spill over to

non-Medicaid clients also. So we have staff there on site to coordinate the transportation. They were able to demonstrate that in having that presence they were able to free up medical staff time to get out of the business of transportation. Rather than the social workers, discharge nurses doing it—now it’s transport staff.” –Brokerage

“Most of the operators had a positive experience—did it at a fully allocated cost. Role of NEMT has been leavening for rural transit has allowed rural communities to do amazing things.” –Consulting/technical assistance

“From the transit’s perspective, by setting up this model, compared to what it would have been if we had done it the traditional way of more individual rides which we are obligated to do, we’re saving between $25,000 and $30,000 a month.” –Transportation services

Sharing Data, Analyzing Solutions

While interviewees discussed many hurdles to sharing information between health care and transportation providers, some solutions emerged as well, ranging from Business Associates agreements to meet HIPAA requirements to housing transportation staff within the hospital or clinic. Others offered options for avoiding HIPAA issues by asking patients directly for information; some of these same solutions are included in the next section—“Available Information.”

“Main programming is the navigator, and the navigator will work for the clinic. [Nonprofit organization] will bring the coalition together, hire someone to analyze the data we get, but the clinic is going to implement the program. [This structure] got us a lot of things—they can watch someone from the day they walk in to the day they deliver, can follow people and see what their birth outcomes are, how are people who use the navigator working out, compare that to outcomes for people who aren’t using the navigator.” –Human services

“We also got a grant from [funders] who have come together looking at technology to get data. We’re going to collect feedback from patients through SMS. After somebody goes through the program, they’ll get a text, and we’ll ask them questions and get feedback outside of HIPAA. We’ll get information from them pretty close to the time they’re receiving the services; [a nonprofit organization] will be collecting that data—more about customer service than outcomes.” –Human services