3

Cross-Sector Collaboration to Provide Transportation Services in Urban Settings

In urban areas, public transport traditionally plays a very significant role and is a very important part of the solution for bringing people to health care, said session moderator Nigel Wilson, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Public transport is not the entire solution, however, and panelists in this session shared examples of cross-sector collaboration to provide transportation services to health care in urban areas. Ann Lundy (via telephone), the vice president of Medicaid clinical operations in government programs at Health Care Service Corporation (HCSC), offered the perspective of a major health insurer, and described telemedicine as one solution to linking patients to care.1 Perry Meadows, the medical director for government programs at Geisinger Health Plan, shared several real-life examples of where transportation and health care intersect. Yahaira Graxirena, a transportation planner at the Central Massachusetts Regional Planning Commission, and Xavier Arinez, the chief executive officer of the Worcester Family Health Center (FHC) discussed using geocoding to develop solutions and improve access to primary care for low-income and minority individuals. Mary Blumberg, the program manager for strategic planning and development at the Atlanta Regional Commission, described several examples from the Atlanta area of programs that increase patient knowledge about transportation options and strive to decrease unnecessary hospital readmissions. Finally, Katherine Kortum, a study director at the Transportation

___________________

1 HCSC is the parent company of the Blue Cross and Blue Shield subsidiaries in Illinois, Montana, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas.

Research Board (TRB) of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, provided an overview of the TRB study Between Public and Private Mobility: Examining the Rise of Technology-Enabled Transportation Services.

The presentations were followed by comments from discussants Jana Lynott, a senior strategic policy advisor for AARP; Barry Barker, the executive director of the Transit Authority of River City (TARC) in Louisville, Kentucky; Valerie Lefler, the president and chief executive officer of Liberty Mobility Now, Inc.; and Art Guzzetti. (Highlights are presented in Box 3-1.)

TELEMEDICINE TO SUPPLEMENT IN-PERSON VISITS

The Code of Federal Regulations requires states to ensure that eligible and qualified beneficiaries of Medicare and Medicaid have nonemergency medical transportation (NEMT) benefits, Lundy said. The transportation covered varies by state and is affected by such factors as geography and available modes of transportation. Providing NEMT can be particularly challenging in rural settings. This benefit does not cover transportation to other services that the patient might also need, such as community resources, food pantries, or counseling services, and Lundy suggested that there is room for improvement in this benefit. Depending on the beneficiary’s needs and the state rules, NEMT services can be provided by taxi, personal car, public transportation, or other options. There are issues with each of those modes, Lundy said, especially around scheduling and the need for the beneficiary to be on time for certain treatments (e.g., dialysis, radiology services).

Lundy highlighted the ability of telemedicine to help address transportation to care issues. Some potential advantages of a telemedicine approach include reduced transportation costs, timeliness of appointments, efficient use of providers’ time, increased access to specialty services or consultations, reduced numbers of emergency department (ED) visits for nonemergency care, a decreased risk of injury or disorientation for the beneficiaries (from not having to travel), and the ability to provide some preventive care and wellness screenings. With the implementation of electronic health records, a video visit could be stored in the patient’s medical record, providing a real-time visual record of the visit. Telemedicine does not need to stand alone, Lundy stressed. Rather, it can enhance an existing relationship that the beneficiary has with a facility, local hospital, or clinic; augment care and treatment plans that are already in place; and solve some of the transportation challenges by reducing the need for travel.

THE VALUE OF RELATIONSHIPS IN PROVIDING SERVICES

Meadows shared several examples from his experience at Geisinger Health Plan of cases where transportation and health care intersected. The first example involved a 65-year-old patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and debilitating pain. During her first 6 months of eligible coverage with Geisinger, the patient had 15 ED visits. She lived 15 blocks from her primary care provider’s office but only two blocks from the ED, and because she did not have a car or money for transportation, it was easier to call emergency medical services and go to the ED. The patient also had 10 inpatient admissions related to the ED visits, and Meadows said that the cost of care for the ED visits and subsequent inpa-

tient hospital admission was significant. Geisinger assigned a case manager to the patient, and although it took some time for the member to really trust the case manager, they were able to implement some solutions. The case manager arranged for taxi vouchers for the patient to be able to visit her primary care provider. During the following 5 months, the patient had only two ED visits, both resulting in inpatient stays related to her chronic kidney disease. The taxi vouchers have also allowed the patient to travel to her dialysis appointments and the pharmacy. Meadows said that although the cost of outpatient care for this member has increased (i.e., primary care visits, dialysis, medications), her inpatient costs were significantly reduced. Most importantly, Meadows said, the patient’s quality of life has improved, and she is healthier and happier.

Another example is the Geisinger special needs unit, which is intended specifically for the Medicaid population. This model involves nurse case managers and social workers as well as community health workers who live in the area and can connect with the residents. One patient served by the special needs unit is a 42-year-old member with congestive heart failure, COPD, and diabetes who at one point weighed 600 pounds. This individual would require a bariatric ambulance to get to each of his doctor’s appointments. A community health associate was able to arrange for all of this patient’s providers to see him at one office in the hospital, during one day, over one 8-hour time period. The patient was transported by bariatric ambulance and was able to get all of the services he needed in one place. He has since had his bariatric surgery, has lost almost 300 pounds, and has improved health and quality of life. There was increased total cost based on the surgery, the inpatient stay, professional services, and pharmacy, Meadows said, but the end goal was improved health and quality of life.

The next example Meadows described was of a 3-month-old child diagnosed with retinoblastoma. This child needed transportation from Scranton, in northeast Pennsylvania, to a specialist in Philadelphia. The Medical Assistance Transportation Program in Pennsylvania will not cross county lines, and taking the shortest route to Philadelphia would require this patient to cross five county lines. This would have required this 3-month-old member and his mother to stand on a street corner, waiting for the next county service to pick them up, Meadows said (if they were picked up at all). A community health worker was able to use his local contacts to have a limousine service transport the child to the children’s hospital in Philadelphia. Meadows added that this same community health worker just happened to be at a doctor’s office when the para-ambulance that dropped a patient off could not be contacted to pick the patient up to take her home. The office was closing soon, so the community health worker used his contacts with one of the ambulance services to arrange transport for her at no charge.

The critical element in all of these example, Meadows said, is a relationship. Whether it is a relationship between a case manager and a health plan member or between a community health worker and local service providers, the relationship involves people working together to improve the health and quality of life of patients and plan members.

TRANSPORTATION PLANNING TO IMPROVE ACCESS TO PRIMARY CARE

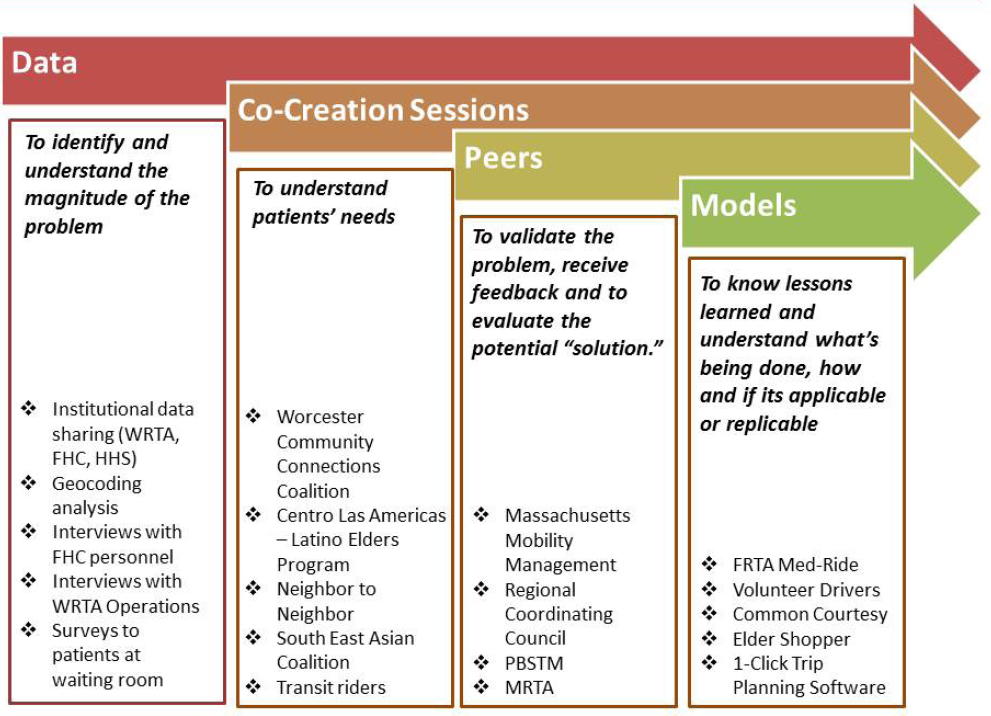

The Central Massachusetts Regional Planning Commission handles all of the planning for the Worcester Regional Transit Authority, Graxirena said. Through the National Center for Mobility Management design challenge and the Community Transportation Association of America (CTAA), the Worcester team was able to explore solutions for improving access to primary care for low-income and minority individuals who receive health care services at the Worcester FHC. The design challenge opened the door to collaboration, which was essential to understanding the patients’ transportation needs and the magnitude of the problem, she said. She described the process and partners across four levels of collaboration: data collection to understand the magnitude of the problem, co-creation sessions to understand the patients’ needs, discussions with peers for feedback and evaluation of solutions, and consideration of lessons learned from other models (see Figure 3-1).

The Worcester Regional Transit Authority registered more than 3 million passenger trips in 2015, Graxirena said. Twenty percent of all transit trips are for medical purposes, and the FHC is among the top 50 high boarding and alighting locations. Data collection for the design challenge began with a geocoding analysis done in association with the FHC. Graxirena and her Worcester FHC colleague Arinez both noted the challenges of sharing data across sectors and said that tools were developed to allow the sharing of patient information with the transportation authority without compromising patient privacy. For example, instead of seeking transportation data for the patient who lives at 200 Main Street, data would be collected for all the patients who are coming to the FHC from 0 to 500 Main Street, so individual patients could not be identified.

The geocoding analysis showed that even though the majority of FHC patients had access to nearby transit (living within 0.25 miles of a transit route), they needed to transfer through the main transit hub to reach the FHC. Some trips could take up to 3 hours. Overall, around 70 percent of FHC patients do not have a car and need some type of transportation arrangement (45 percent use the transit service, 15 percent share a ride, 10 percent use a livery service). Some patients said they cannot afford the bus fare. The FHC logs an average of 800 missed patient encounters per month,

NOTE: FHC = Family Health Center; FRTA = Franklin Regional Transit Authority; HHS = U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; MRTA = Montachusett Regional Transit Authority; PBSTN = Paratransit Brokerage Services, Transit Management, Inc.; WRTA = Worcester Regional Transit Authority.

SOURCE: Graxirena presentation, June 6, 2016.

at a financial loss for the FHC of nearly $1.5 million per year (at a rate of $154 per person per visit). The geocoding analysis found that 51 percent of patients had missed an appointment due to a transportation problem, which translates to a loss of nearly $740,000 for the FHC as a result of missed appointments due specifically to transportation problems.

Arinez said he was aware that transportation was an issue for many of his patients at the FHC, but he said he did not have the time or resources to do anything about it and was concerned that any attempts at change could take many years. Despite these reservations, the FHC embraced the design challenge project. One proposed solution was to integrate the scheduling of appointments with the bus schedule. The call center determines where patients are coming from and what routes they will take and schedules accordingly so the travel time for each patient is the shortest possible. Another solution is for the FHC to pay for a 1-day transit pass for patients at a cost of $3.50 each. It was calculated that 180 FHC patients daily use

the Worcester Regional Transit Authority to get to the FHC. This would be a daily expense to the FHC of $630, or an annual expense of about $158,000 (based on 251 weekdays). This cost is only about 10 percent of the FHC annual loss due to missed appointments. Providing a transit stipend to patients who use it as their only means of transportation to access their primary care could lead to a significant savings for the FHC.

In closing, Arinez said that primary care systems are already at the limit and that there are not enough physicians in the United States to handle the increasing demand resulting from health care reform and increased coverage. In reducing missed appointments and increasing patient access to care, it will be important to also consider how to manage the increased burden on doctors and to avoid such problems as burnout and reduced quality of care.

STRATEGIC PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT

The Atlanta Regional Commission is both a metropolitan planning organization, which is responsible for transportation planning, and an area agency on aging, Blumberg said. She said that the transportation programs are supported through many different funding streams, each with different requirements, reporting, and unit definitions, making it challenging to compare data across programs. Blumberg shared several examples of transportation programs that the commission is working on.

Bridge to Consumers

“You can have the best programs in the world, and if you don’t have a bridge to the consumer, it really does very little good,” Blumberg said. In particular, it is important that people know how to find the services. Through a grant from the FTA Veterans Transportation and Community Living Initiative, the Atlanta Regional Commission developed the Simply Get There trip discovery tool.2 The tool, which is unique to the Atlanta region, pulls information from two different databases that are constantly updated, the area agency on aging service database (called ESP) and atlantatransit.org. The responsive design is meant for use with tablets, smartphones, and computers. Simply Get There covers specialized transportation, but at this time it does not have scheduling capabilities, Blumberg said. Travelers plan their trip in several easy steps: select the origin and destination of the trip; select specialized services if needed (e.g., wheelchair accessibility); select acceptable trip options (i.e., consumer chooses modes such as walk up to a half a mile, bus, train, vehicle for hire); and then

___________________

2 See http://simplygetthere.org (accessed August 4, 2016).

review and select the travel plan based on personal factors (e.g., cost, time of arrival, length of travel). The project is now in phase 2 of development, and through an FTA Mobility Services for All Americans grant the application capabilities will be expanded to allow for trip transactions (e.g., centralized eligibility, booking, scheduling, dispatching, payment). The intent is to eventually release the design as open-source software so that others can use it, Blumberg said.

FTA Section 5310 Program

Blumberg shared some data regarding the Atlanta Regional Commission’s FTA Section 5310 program.3 The Atlanta region has about 4.5 million people in 10 counties, but only three counties are covered by major train or bus systems, and many of the outlying counties have large gaps in transportation services. The Section 5310 program operates primarily through vouchers and serves 1,274 unduplicated riders per month. The majority are older than age 65 (82 percent), while 31 percent are persons with disabilities, and 17 percent are below the poverty level. The majority of trips (57 percent) are classified as personal, including quality-of-life trips (e.g., to the grocery, pharmacy, or senior center). About 39 percent of trips are for medical reasons, and 4 percent are for employment. From a cost perspective, the data indicate that the average Section 5310 program trip length is 12 miles one way, and the average cost to the system of that trip is $21. Blumberg added that mobility management costs are included in this cost-per-trip calculation, which is an important fact to know when comparing across regions as these costs are not always included. For comparison, she said, paratransit is $49.33 for a one-way trip, an average taxi ride costs $26.25, and Uber or Lyft can be anywhere from $15 to $20.

Community-Based Care Transition Program

Another example described by Blumberg was a community-based care transition program aimed at reducing all-cause 30-day readmissions for Medicare fee-for-service patients by 20 percent across six hospital partners. This intervention, funded by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, had multiple components, including community health worker coaches who followed patients for 30 days post discharge, and assisted them with self-management skills. The area agency on aging also sought to

___________________

3 For more information on FTA funding granted under Section 5310—Enhanced Mobility of Seniors and Individuals with Disabilities (49 U.S.C. 5310), see https://www.transit.dot.gov/funding/grants/enhanced-mobility-seniors-individuals-disabilities-section-5310 (accessed August 4, 2016).

address some of the social determinants of health, and enhanced services under the program included home-delivered meals, homemaker services, and transportation. Blumberg noted that these services were only for the 30-day post-discharge intervention.

Between October 1, 2014, and January 31, 2016, the program served 8,400 people. Only 6 percent (464 people) were enrolled in and receiving transportation services. The baseline readmission rate was 19.4 percent. The standard intervention reduced readmissions to 15 percent, and for those receiving transportation services readmission was reduced to 7 percent. It is not possible to attribute this further reduction specifically to transportation, Blumberg cautioned, as other services (e.g., meals) might have contributed, but it is a very interesting observation. Total Medicare cost savings from the reduced readmissions for the cohort without transportation services (n = 7,937) was calculated to be $236,544, while the total savings for those receiving transportation services was nearly $400,000, even though it was a much smaller number of people (n = 464). Those receiving transportation services were also 7 percent more likely to make it to their follow-up appointment within 14 days of discharge.

Opportunities

Blumberg shared her perspective on some of the challenges and opportunities for implementing transportation services. More funding flexibility at the local level would allow for more innovation, she said. For example, the Section 5310 funding program goes though the state agency, and there are layers of rules, mainly designed for traditional transportation fleets, that are imposed on Atlanta’s Section 5310 programs (e.g., required training in cardiopulmonary resuscitation) that add burdens to testing innovations. Although Uber or Lyft may have some safeguards, insurance, and training for drivers, they do not have health-related training, and this is a barrier when attempting to pilot innovative approaches with such services. Another area where flexibility is needed is transportation for dialysis patients. Dialysis centers benefit greatly from patients having reliable transportation, yet federal rules prohibit the Atlanta Regional Commission from approaching patients to be reimbursed for transportation services.

Blumberg also highlighted the importance of designing programs at the outset to address predefined research questions and capture the necessary data. She recommend testing a multi-funding data pilot in which several programs would agree to some common research questions and collect uniform data across all the multiple data sources of the programs.

Another opportunity is improving provider capacity through training and education combined with implementing technology to efficiently deliver services and capture data. Some rural areas are still capturing data with pen

and paper, Blumberg said. Travel training is also needed, not only for consumers, but also for health care providers, social workers, and caseworkers, Blumberg said.

Moving forward, the Atlanta Regional Commission will continue to test and improve data collection to measure program outcomes and drive system improvements, she said. The ultimate goal, Blumberg said, is to maximize transportation dollars by matching consumers’ desires and abilities to the right level of service for them.

OVERVIEW OF THE TRB STUDY BETWEEN PUBLIC AND PRIVATE MOBILITY

In December 2015, TRB released its findings from an 18-month study of shared mobility services in Special Report 319, Between Public and Private Mobility: Examining the Rise of Technology-Enabled Transportation Services (TRB, 2016). The report considered a wide range of policy issues surrounding different mobility services, and Kortum provided a brief overview of the findings most relevant to the issue of health care access.

There are many innovative mobility options and services that are changing the way that people get around. Some example are car sharing, bike sharing, taxis, transportation network companies (e.g., Uber, Lyft), and microtransit services.4 Most of these mobility services are based around smartphone applications, and the report discusses the equity concerns associated with the growing dependence on smartphones for these services. Smartphones tend to be fairly prevalent across a wide range of income spectrums, Kortum said, but there is an age divide that exists with smartphones and other technology that is causing accessibility concerns.

There are also both accessibility benefits and drawbacks of smartphone-application-based mobility services for people with disabilities. Blind persons, for example, have long had difficulty hailing a taxi on the street, and an app-based service can help to overcome this. There are advantages to making a digital payment through smartphone mobility applications. For example, there is no question about what money the person is handing over or what change was received. Kortum noted that there have been some issues regarding service animals, including animals being placed in the vehicle trunk, or drivers denying the passenger the ride. Because Uber and Lyft drivers are independent contractors and not employees, those trans-

___________________

4 As defined in the report, microtransit “encompasses flexible private transit services that use small buses (relative to traditional transit vehicles) and develop routes based on customer input and demand” (TRB, 2016, p. 17). Examples of microtransit service companies [at the time of report publication] include Bridj, Loup, and Chariot.

portation network companies have a limited amount of control over driver behavior and availability, but they are working to address these issues.

Another potential barrier to accessing mobility services that are based on smartphone applications is the need for a bank account or credit card for payment, since some estimates suggest that 20 percent of the U.S. population have neither bank accounts nor credit cards. There is a lot of overlap between the vulnerable populations that need these transportation services and those who do not have smartphones or bank accounts.

Kortum suggested that taxis are currently somewhat better suited for handling health-related trips, in part because taxi drivers tend to have more experience with helping people who need assistance in and out of a vehicle. There is also a long history of cooperation between paratransit agencies and the taxi industry. Kortum said that people in wheelchairs are only a small subset of the paratransit population. Many people in need of paratransit can ride in regular vehicles, but they just do not have easy access to them (e.g., transit routes are not near enough, transit stops are not accessible). Paratransit agencies often partner with local taxi companies to provide rides for these individuals. Transportation network companies are very interested in getting into this market, Kortum said. An advantage of paratransit partnering with Uber or Lyft is that these services are not subject to the same jurisdictional restrictions that much of the taxi industry often is. Shared mobility services are working toward improving access, including allowing people to call into a central dispatch system (eliminating the need for a smartphone application), allowing riders to specifically request a wheelchair-accessible vehicle, and having drivers who are trained to help people in and out of a vehicle.

In some places, low-income individuals (e.g., those on welfare or receiving food stamps) are eligible to receive reduced-cost bikeshare passes, Kortum said. The Boston Medical Center has launched a program called Prescribe-a-Bike, in which doctors can prescribe a free bikeshare membership for their low-income patients, which provides both a means of transportation and a healthful activity. The city of Birmingham, Alabama, has partnered with Blue Cross to provide “pedelecs,” electric pedal-assist bicycles that make it easier to participate in shared mobility throughout the year. One public health issue that has come up regarding bikeshare, Kortum said, is whether helmets should be required and whether that would deter people from using the bikeshare.

The TRB study also reviews the wide range of policy and planning issues surrounding shared mobility.

DISCUSSION

Following the presentations, panelists, discussants, and participants discussed a variety of issues, including the data resources available to participants and some issues related to data collection; collaboration and partnerships; the challenges of existing rules and regulations; and the location of health services relative to the users of those services.

Data Collection and Resources

Lynott apprised participants of the AARP Public Policy Institute’s new Livability Index,5 which uses data from more than 50 different sources to score the overall livability of neighborhoods and communities, as well as providing scores in seven categories (housing, neighborhood, transportation, environment, health, engagement, and opportunity). Transportation-related data include such factors as speed limits, transportation-related injuries and fatalities by neighborhood, the environmental footprint and adverse health effects of transportation, near-roadway pollution, healthy and safe transportation options, the availability of public transportation services, state support for volunteer driver programs, coordinated human services transportation, and enhanced mobility for older adults and people with disabilities. There are also data on neighborhood characteristics that support health, such as walking trips per household per day, the general walkability of the neighborhood environment, and proximity of grocery stores. The next phase of research, Lynott said, will be to combine the livability data with other major federal datasets and health datasets to study how those community characteristics affect health.

Lynott also mentioned the National Household Travel Survey, which reviewed travel trends from 1969 through 2009. From 1983 through 2009, trips for medical purposes increased 187 percent, she said. This increase was consistent across all age groups (i.e., it was not due to population aging) and was likely related to major changes in the health care sector and in how people access health care, which led to greater demand. All Americans have to travel more to access health care than they have in the past, she said.

With regard to data collection for assessing value, Lynott suggested that there is a need not only to consider fixed route public transportation, but also to demand responsive transportation. Data should show not only whether there is transit service to a particular county, but also the true availability of the service (e.g., hours of the day and days of the week that

___________________

5 Graphics, metrics, and other resources available at https://livabilityindex.aarp.org (accessed August 4, 2016).

service is available). She also noted the need for transit providers to upload their data to the Google Transit Feed Specification (GTFS).6 The AARP Livability Index used GTFS data, so if a state has not uploaded its data, even though it may have transit in every county, it is getting scored very low on those indicators.

Community Collaboration

Lynott asked the panel whom the transportation community should reach out to in the health care community to start a collaboration in their area. Meadows said that in a large health plan, such as Geisinger Health Plan, it would be someone like himself (e.g., the medical director for government programs). Specifically, he recommended approaching the health care side first (e.g., the head of case management, the chief medical officer) and let people on that side take it to the finance department. If they can show a health care benefit, they can get buy-in from the finance side. Arinez agreed and added that it takes some effort from health care organizations to think about the entire visit cycle, from the time a patient leaves home to the time he or she returns. An hour-long office appointment could be a 6-hour event for the patient. Graxirena said that the Worcester Division of Public Health, through the Community Health Improvement Plan, is leading the conversation between the transit agency and the health care facilities, health care providers, and other community organizations. Gomez said that hospitals now have standardized community benefit requirements,7 and he suggested approaching hospitals to consider transportation as part of their community benefit efforts.

Lefler asked if there were any examples of how an urban and a rural transit system partnered to improve access to care or provide last-mile assistance. Graxirena said that in Worcester the transit authority has agreements with other transportation providers outside the fixed route. This allows for the transportation of people to their jobs, medical appointments, or other areas that are outside the paratransit service boundary.

___________________

6 GTFS “defines a common format for public transportation schedules and associated geographic information. GTFS ‘feeds’ let public transit agencies publish their transit data and developers write applications that consume that data in an interoperable way” (https://developers.google.com/transit/gtfs [accessed August 9, 2016]).

7 Such requirements were imposed on tax-exempt hospitals and health systems by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act under the Internal Revenue Code, and they standardize “what counts as a community benefit” and require “specific information about [hospital] policies and practices relating to community health needs assessment, financial assistance, hospital charges, billing and collections, and the other new federal requirements for charitable hospitals” (http://www.hilltopinstitute.org/publications/WhatAreHCBsTwoPager-February2013.pdf [accessed August 8, 2016]).

Barker reiterated the comments by panelists about the value of relationships and of embedding people in partner organizations. Each organization has different languages, motivations, and reward systems. Referring to the transportation authorities and their ability to tackle systemic issues, including access to health care services, Barker also urged health sector colleagues to “come to us with what you need. Let us figure it from there, because there’s some very creative ways to do it.”

Rules, Regulations, and Safety

Barker expressed concern about being so laden with rules and requirements that it is difficult to meet customers’ needs or implement solutions. In addition, customers should not have to become experts in transportation regulations to be able to use the services. Barker suggested that there is a need for more ombudsmen who can help people navigate the system on a one-to-one basis.

Kortum underscored the need for creating flexible, guiding regulatory policies that are in everybody’s best interest, as opposed to those that are largely mirroring the status quo for the transportation industries that already exist (e.g., taxis). There are ways, through regulations and policy, to create more partnerships. Some cities are moving in this direction, she said.

A participant raised the issue of safety when sending patients via transportation network companies. He noted that Uber and Lyft recently suspended operations in Austin, Texas, because of a regulation requiring improved background checks (including fingerprinting). He highlighted the need for transportation network companies to work with the health care sector to reduce the risk of lawsuits in contracting patient transport services to Uber or Lyft. Kortum pointed out that the taxi industry is required to fingerprint drivers, and the practice is common in a variety of professions that have a public safety aspect (e.g., school employees). Uber and Lyft require background checks conducted through background check providers, which include driving history and criminal background checks based on name and birthdate. Kortum added that there has been no analysis regarding which approach provides a more complete background check (fingerprints versus name, birthdate, and Social Security number). Fingerprinting is considered standard practice, but there are time and financial costs associated with fingerprinting, and the benefits over other background check methods are not clear.

Land Use and Location of Health Services

Guzzetti raised the issue of land use and the need to locate health care services in places where they can be accessed. Blumberg said that in light

of changing demographics (people living longer and a growing cohort of older people), it is even more critical that transportation, housing, and health care all be connected. Developers have been branding it as new urbanism, and consumers are demanding more walkable, livable communities. Gomez highlighted the value of locating community health centers near transit stops. He said that this does not necessarily occur to developers, and he encouraged participants to discuss this with their community health centers as they are building new access points. Guzzetti observed that connecting transit to airports has become a focus for many cities because it draws conventions and tourism. Some cities have started to do this for health as well. Cleveland, for example, has a bus rapid transit line—the Healthline—that connects to city health facilities. He wondered how the “branding” of transit and health linkages could be enhanced, as has been done for airports linked to cities.

Kortum observed that some cities are looking at shared mobility in lieu of parking. In San Francisco, for example, some developments are providing vouchers for transit in lieu of parking for residents who do not bring a car. Car sharing and bike sharing are also becoming popular amenities for new developments, specifically in urban centers, and some new residential developments are providing dedicated car-sharing spaces in their parking garages.

Arinez said that the Worcester FHC is collocating services in one building, including dental, radiology, vision, behavioral health, and pharmacy services. An outcome of this that insurance companies should be aware of is that when the patient cannot make it to the office, he or she is missing six appointments, not one, and it is a significant financial loss.

This page intentionally left blank.