2

Approaches to Reducing Response Burden

In his opening remarks, Steering Committee Cochair Joseph Salvo (New York City Department of City Planning) set forth a framework for the workshop that emphasized the importance of the American Community Survey (ACS) to the economy and the functioning of governments at the federal, state, and local levels. He also considered the threat to the survey posed by those who see it as an unnecessary burden and a threat to privacy. The importance of the survey, he said, “puts extraordinary pressure on the Census Bureau to not only educate the nation on the importance of the ACS and meeting the needs of our democracy, but to execute the survey in a manner that maximizes efficiency and minimizes burden.”

Salvo emphasized that the steering committee adopted a broad view of burden. Burden is not simply the length of the questionnaire or the time needed to complete it, he explained, but also the perceptions of burden that come from many sources, including a respondent’s views about government. He noted the perception of burden is difficult to measure, but it can be increased or alleviated by the materials that accompany the survey, the means of contact, and the perceived relevance or intrusiveness of the questionnaire. He challenged the participants to address the workshop goal of providing the Census Bureau with guidance for short- and medium-term solutions that do not require lengthy and/or expensive research.

CENSUS BUREAU CHANGES TO REDUCE RESPONDENT BURDEN

Deborah Stempowski (chief of the ACS at the time of the workshop)1 observed that an all-inclusive definition or description of response burden does not exist—every person might identify the components of the definition differently. She noted that the estimate of 40 minutes to complete the survey is viewed by some respondents as intrusive, as is the number of contact attempts. Other aspects of burden include the ease or difficulty in providing answers to the questions and respondent concerns about the need for the information requested. Some respondents are concerned about perceived intrusiveness on the part of the government and question why the survey is mandatory, she said.

The report Agility in Action: A Snapshot of Enhancements to the American Community Survey (U.S. Census Bureau, 2015a) constitutes a plan for approaching the issues of response burden. Stempowski summarized a number of initiatives in the report that have formed the basis for the Census Bureau’s approach: creation of the position of respondent advocate; fewer computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) contact attempts; a new brochure, “Why We Ask”; refresher training for staff in contact centers and field representatives; some change in the content of the survey; reduction in the number of mail contacts; individual performance coaching for the field interviewers; and enhancement of the Internet part of the survey. She explained each change in more detail:

- Respondent advocate Stempowski reported that the position of respondent advocate, created in April 2013, was designed to resolve respondents’ concerns. The advocate responds directly to issues raised by respondents and interacts with other stakeholders, including Congress. She said the advocate “is an ear to the ground” and helps guide improvements in data collection, the questions, and operations of the correspondence control unit and the call centers.

- Fewer CATI contact attempts The Census Bureau conducted research to model the possible effects of reducing the number of contact attempts. Stempowski noted that CATI software permits changing the parameters. After the research and Agility in Action report, revised contact stopping rules were implemented. The result was a reduction in CATI log-in hours of about 17 percent while the CATI response rate dropped only about 5 percent. The Census Bureau is now planning similar changes in its computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI) operations in June 2016, which will

___________________

1 Deborah Stempowski became chief of the Decennial Management Division of the Census Bureau since the workshop and, at the time of this publication, had been replaced on an acting basis by Victoria Velkoff.

-

allow developing a score that reflects total contact attempts across mail, telephone, and personal visits.

- “Why We Ask” brochure A brochure has been prepared to provide respondents with information on why the ACS asks certain questions. The brochure addresses the benefits of responding in personal terms. Stempowski characterized the main message as “what is in it for me?”

- Refresher training for staff in CATI contact centers and field representatives The new training has been completed for staff in CATI contact centers and is scheduled to begin late in 2016 for field interviewing staff. The training reinforces the basic principles of reducing burden and treating respondents respectfully and professionally. It includes information on response conversion to persuade, without being too pushy, a reluctant person to participate.

- Content changes As noted above, a question on flush toilets has been deleted, as has the question on whether a business or medical office operates on the property. A question on computer and Internet use was revised to improve its currency.

- Reduced mail contacts The ACS employs a number of mail contacts in the process of soliciting responses. At the time of the 2015 National Research Council ACS review (National Research Council, 2015, p. 47), the first mailing was a prenotice postcard, followed by an advance letter that alerted sample members to the survey and encouraged participation. The letter was followed by a mail package, which included instructions for how to respond through the Internet. A reminder postcard was sent a few days after the mail package. Sample members who did not respond after the reminder postcard were sent a replacement mail package, which included a paper version of the questionnaire and a postage-paid envelope for a mail response. Instructions for responding by the Internet were also included. The package was followed by another postcard reminder. Sample members who did not have a telephone number that could be used for telephone follow-up received an additional postcard, alerting them that a field representative would be contacting them in person if they did not respond by mail or Internet. In 2015, the Census Bureau eliminated the prenotice postcard, and it has also accelerated the initial mailing date to increase the likelihood of self-response before the respondent receives the paper questionnaire.

- Individual performance coaching for field interviewers Though expensive, one-on-one coaching is valuable to provide feedback and reinforcing reminders, Stempowski said.

- Internet instrument enhancements In the past, the ACS had a single annual updating of the instrument at the beginning of the survey

year. A midyear updating each July makes improvements instead of waiting until the beginning of the next survey year. The Census Bureau is taking advantage of the midyear update in 2016 to (1) add security questions so respondents can create their own personal identification numbers (PINs), (2) highlight the write-in boxes to make them easier to see on a computer screen, (3) improve transitions through the instruments by consolidating and streamlining questions so they are easier to follow, and (4) add the “Why We Ask” text to the Internet instrument.

DEFINING, MEASURING, AND MITIGATING RESPONSE BURDEN

Scott Fricker (Bureau of Labor Statistics [BLS]) provided a brief overview about how response burden has been treated in the broader survey literature and shared the results of some of the burden-related research that he and his colleagues have been doing at BLS.

Response burden is important, he stated. In addition to ethical considerations of overburdening respondents, burden affects the quality of survey products. The continuing downward trend in response rates for most surveys has increased concern about the effect of burden on nonresponse, including panel attrition. He stated that establishment surveys are particularly concerned with delayed responses that affect initial estimates. Burden also can affect quality among survey participants, through item nonresponse and breakoffs, and it may cause less effortful, less accurate reporting by respondents.

Fricker said that dealing with the consequences of respondent burden has significant financial costs for survey organizations. Those costs include efforts to engage and secure the cooperation of sample members (through increased contact attempts or more elaborate and costly persuasion efforts), as well as procedures for dealing with suboptimal data (through editing and imputation). In his view, broader consequences include negative evaluations of surveys in general that negatively affect survey participation.

The importance of burden underscores the importance of appropriately conceptualizing and measuring it. Fricker described two approaches to measuring burden. The most common approach, historically, has been to equate burden with the length of the interview. This concept of “burden” relies on objective measures, such as the estimated total time, effort, and financial resources expended by the survey respondent to generate, maintain, retain, and provide survey data (U.S. Office of Management and Budget, 2006, p. 34); the interview duration (Groves and Couper, 1998, p. 251); or the number and size of the respondent’s tasks (Hoogendoorn and Sikke, 1998, p. 189). Fricker said that in the absence of any additional information, these objective measures seem appropriate, especially survey

length. However, the research is somewhat mixed in terms of how well they predict survey outcomes.

The second approach to measuring burden, he stated, is grounded in the psychological underpinnings of respondents’ experiences in a survey. He referred to Bradburn’s (1978) seminal work that identified four factors that contribute to respondent burden: (1) length of the interview, (2) amount of effort required by the respondent, (3) amount of stress experienced by the respondent, and (4) frequency with which the respondent is interviewed. In addition to underscoring the multidimensional nature of burden, Bradburn emphasized that “burdensomeness” is a subjective characteristic of the task, “the product of an interaction between the nature of the task and the way it is perceived by the respondent” (p. 36).

Along these lines, a number of researchers have focused on trying to capture the subjective nature of burden, most often using self-reports and interviewer notes. Self-reports measure respondent perceptions of a survey’s characteristics (Sharp and Frankel, 1983; Hoogendoorn, 2004; Fricker et al., 2011, 2012); attitudes about the importance of the survey, about government, and similar entities (Sharp and Frankel, 1983); negative feelings (e.g., annoyance, frustration, or inconvenience) (Frankel, 1980); and perceptions of time associated with the response task (Giesen, 2012). Interviewers’ notes are used to obtain respondents’ complaints about survey burden (Martin et al., 2001).

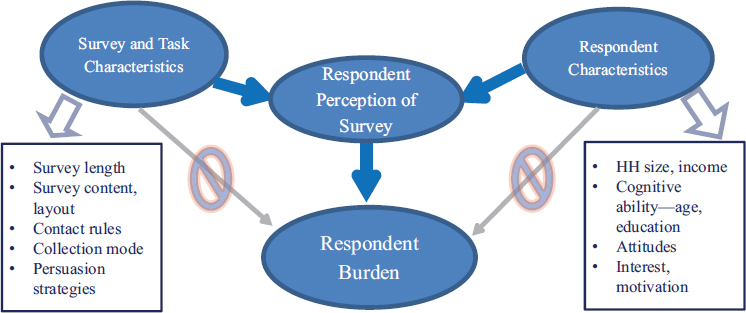

These measures can be summarized in a conceptual model of burden. Fricker laid out the model used at BLS, which considers the objective burden and the characteristics of respondents (see Figure 2-1). The objective burden is measured by length, question content and layout, contact rules, collection mode, and persuasion strategies. The characteristics of respondents cover their cognitive capacity, motivation, attitudes about this survey or surveys in general, confidentiality concerns, and factors that might make the survey task more or less difficult, for example, household size.

Fricker described the BLS research focus on understanding respondents’ subjective experiences of participating in the Consumer Expenditure Survey. BLS began by conducting a thorough review of the literature related to burden—both in the research on survey methods corpus and in psychological studies and studies of burden in medical caregivers—to identify areas likely to contribute to burden in the survey context. The study took the perspective that burden is a multidimensional construct, and it is important to identify features or dimensions that contribute to it. BLS then developed questions to assess those dimensions and administered them to respondents after their final interview (see Box 2-1).

With these data in hand, BLS evaluated the performance of burden-related items through five methods: (1) small- and large-scale analyses (cognitive and psychometric testing and field experiments), (2) multi-

NOTE: HH = household.

SOURCE: Scott Fricker presentation at the Workshop on Respondent Burden in the American Community Survey, March 8, 2016. Available: http://sites.nationalacademies.org/cs/groups/dbassesite/documents/webpage/dbasse_173169.pdf [October 2016].

variate models of burden, (3) methods to produce a summary burden score, (4) associations with key survey outcomes, and (5) research into design features that impact burden dimensions.

Fricker summarized several findings. First, the research found consistent support for a multidimensional concept of burden—individual components or latent factors—such as respondent effort, item difficulty, and attitudes about length or sensitivity. All these factors contributed uniquely to respondents’ overall assessments of survey burden. It also showed the importance of including respondents’ subjective reactions in models: doing so improves model fit and strengths of association with survey outcomes. Looking at the individual contributions of objective measures of burden and more subjective metrics in these models, Fricker concluded burden is most highly associated with perceptual measures. Objective survey features, such as length and number of call attempts, have only a small direct impact on burden.

The major finding of the study, Fricker said, was that psychological experiences or reactions to those characteristics are the main drivers of burden perceptions. Fricker concluded the modes of data collection do not affect the overall structure of the model. The same factors have the same effect on burden regardless of whether respondents were contacted mostly by telephone or in person.

In terms of data quality, the BLS research found that intermittent participants who were contacted several times to solicit their response and

to accomplish a “refusal conversion” reported the highest burden. Interestingly, the data collected from these reluctant participants had little influence on the weighted estimates and the regression coefficients. In another test relevant to the ACS, BLS found using a split questionnaire, in which a subsample selected on a matrix basis received a questionnaire with fewer items, resulted in lower burden and in higher data quality.

Fricker turned to an evaluation of the ACS approach. He concluded that the approach is systematic, multipronged, transparent, and outcome oriented, and, therefore, it is likely to be productive. Appropriately, it focuses on the end result—whether the data are “fit for use.” He applauded the selected hybrid approach, which considers both objective and subjective measures, as most likely to lead to additional insights and more targeted interventions. He said he supported the continued content review program.

Fricker suggested possible extensions to the ACS burden research agenda. For example, the Census Bureau might explore use of expert and interviewer ratings of items. He supported a project to solicit additional input from interviewers and added that assessment of the quality of interviewer observations and ratings—how well they track what respondents actually are thinking—might be productive. And he urged continued exploration of paradata.

In summary, Fricker stressed four points to consider when developing a future program to deal with response burden issues. First, perceptions of questionnaire length are affected by many factors, not length alone. Second, perceived length is a driver of burden, but there are many others. Third, the interaction of respondent characteristics with survey features should be a key consideration. Finally, when considering the way ahead, it is important to consider likely effects of intervention/design change on burden dimensions and how those design changes could be evaluated.