5

Measuring Public-Sector Innovation and Social Progress

A motivation for the workshop was the belief that comprehensive measurement of the benefits generated by innovation requires capturing data on a range of activities that goes beyond those traditionally tracked, such as research and development (R&D). Innovation that takes place in the public sector is one area to be explored. Innovation that advances the public good or takes place in ways that accrue outside the market is another. Both topics have featured in discussions about revision of the Oslo Manual and in planning for the next Blue Sky Conference convened by the OECD.

Presenters during this session of the workshop addressed questions that included the following:

- What approaches to innovation measurement can be developed for capturing activities that take place within the public sector?

- Can metrics be developed that go beyond the contribution of innovation to efficiency, effectiveness, or quality in the production of market goods and services?

- Specifically, can the successful exploitation of ideas in the provision of public goods and in the promotion of societal well-being more broadly be measured?

- Are there negative social impacts of innovation that should be considered in understanding of the outcomes of innovation?

MEASURING PUBLIC-SECTOR INNOVATION AND SOCIAL PROGRESS AND INNOVATION INDICATORS FOR THE PUBLIC SECTOR

Fred Gault (United Nations University–Maastricht Economic and Social Research Institute on Innovation and Technology) led off the session with a discussion of the variables that factor into public-sector innovation measurement. He began by proposing an inclusive working definition of innovation:

An innovation is the implementation of a new or significantly changed product (good or service) or process (production or delivery, organisation, or marketing).

And:

A new or significantly changed product is implemented when it is made available to potential users. New or significantly changed processes are implemented when they are brought into actual use in the operation of the institutional unit, as part of making product available to potential users.

He pointed out that the clause “making the product available to potential users” provides a way of broadening the scope to include the public-sector domain and households.

Currently, there is no equivalent to the Oslo Manual or the Community Innovation Survey (CIS) for measuring innovation in the public sector, although both provide models for guidelines and measurement. One problem to be overcome is the need for registers for public-sector institutions comparable to those for businesses, he said, noting the Nordic MEPIN project has made a major contribution in this area (Bloch and Bugge, 2013).

Elsewhere, there has been experimental and evolving work including in the European Union (EU): the Innobarometer (2010)1 attempts to measure the activity of public-sector innovation; the Report on Public Sector Innovation (2012)2 includes case studies; and the European Public Sector Innovation Scoreboard EPSIS (2013) takes on the topic.3 The 2013 scoreboard includes several measures of human resources and of the quality of public services. For the latter, this is the share of organizations and public administration with services, communication, process, or organizational innovations. All the other indicators are indirect or are contextual, which Gault asserted is one of the weaknesses of such scoreboards.

___________________

1Available: http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/flash/fl_305_en.pdf [November 2016].

2Available: http://ec.europa.eu/growth/industry/innovation/policy/public-sector/index_en.htm [November 2016].

3Available: http://bookshop.europa.eu/en/european-public-sector-innovation-scoreboard-2013-pbNBAZ13001/ [November 2016].

Gault noted that the OECD has also pursued work on the public sector, including the Observatory of Public Sector Innovation,4 the STI e-Outlook,5 the Blue Sky Forum 3, taking place in September 2016; and the revision of the Oslo Manual, which started in 2015 and is expected to be complete in 2017. The Observatory of Public Sector Innovation does not include definitions, but it does collect observations about public-sector innovation and, ideally, about best practices. The Science, Technology, and Industry e-Outlook provides a definition of public-sector innovation that is not too far removed from the Oslo Manual: “the implementation by a public-sector organisation of new or significantly improved operations or products.” The OECD Blue Sky Forum, which takes place every 10 years, governs OECD thinking about measurement programs for the next decade. The revision of the Oslo Manual could address broader definitions of innovation that would be a first step toward providing guidance on the measurement and interpretation of innovation in the public sector and the household sector. The Oslo Manual could remain focused on the business sector, but, he commented, if broader definitions are not considered, other organizations may rise to the challenge.

Gault assessed the current state of measurement: Innovation in the public sector can be defined, but a consensus is needed if measurement is to be consistent and comparable. Surveys have been tested, but the results are not comparable over time or across geography. The EU and the OECD are supporting work on public-sector innovation.

Relative to the public sector overall, he said, much less thought has gone into measuring social progress, equity, inclusion, public health, education, and culture.6 He noted the first step is to be able to detect the presence of innovation through surveys or other data collection means. The next step is to ask how innovation contributes to social progress, and how it can be measured. For example, social housing tower blocks in the UK may have qualified as an innovation, but they did not deliver on social progress. Thus, as with the business sector, if value is to be measured, there must be a follow-up survey or use of administrative data. On the policy front, public-sector actions change lives. Innovation policy can act

___________________

4Available: https://www.oecd.org/governance/observatory-public-sector-innovation.htm [November 2016].

5Available: https://www.oecd.org/sti/outlook/e-outlook/stipolicyprofiles/competencestoinnovate/public-sectorinnovation.htm [November 2016].

6Although workshop participant Daniel Sarewitz noted Chris Freeman’s work with the Science Policy Research Unit of the University of Sussex on innovation and social good (see http://www.sussex.ac.uk/spru/about [August 2016]); Nelson (1977); and Lundvall (1992), which includes an understanding of the role of innovation systems for improving conditions in the world.

directly or indirectly to support innovation, but measurement is required to monitor and evaluate policy once it is implemented.

Building on Gault’s discussion, Daniel Sarewitz (Arizona State University) spoke about innovation and social progress with the development of next-generation indicators in mind. He began with the observation that innovation can lead to either positive or negative outcomes, or both. Research is naturally focused on players directly involved in the innovation system, while little thought is given to those who are excluded from its benefits or who are negatively affected. The Internet, for example, sparked destructive progress in a number of ways, he said. While revolutionizing the diffusion of information, it also all but destroyed traditional journalism, for example. Financial innovations led to the subprime mortgage debacle of the late 2000s, which affected broad swaths of society. Thus, the value of innovation often depends on the perspectives of particular segments of society that are affected. He noted that the Luddites smashed power looms in the 19th century because they were going to be displaced from their jobs. They were part of an innovation episode, but they would not be a part that would typically be accounted for in measurements.

Sarewitz also urged workshop participants to keep in mind the idea that innovation and its consequences are sometimes political and normative, arguing that the presence of uncertainty and political elements means that convergence on a canonical consensus set of indicators is not possible. However, acknowledging the normative aspects of underlying processes that lead to both good and bad consequences in a complex society allows for a broader understanding of innovation. As a political process, beyond the winners and the immediate participants in the innovation system, it involves those who may not have as a conspicuous voice in that system.

INNOVATION POLICY

Charles Edquist (CIRCLE, Lund University), speaking from his perspective on the Swedish National Innovation Council, addressed three topics: (1) the conceptual basis for the design of innovation policy, (2) the usefulness of the Innovation Union Scoreboard, and (3) innovation-related public procurement.

Edquist defined innovation policy as encompassing all actions by public organizations that influence innovation processes. A less than straightforward question, he said, is “What actions should be taken by policy makers and what should be done by private organizations?” He suggested that two conditions must be fulfilled for public intervention to be warranted in a market economy. First, private actors must fail to achieve the objectives formulated—a “problem” must exist. Second, pub-

lic actors must have the ability to solve or mitigate the problem. In short, policy makers must identify innovation policy problems and their causes.

In order to identify whether a country or region is doing well or badly with regard to certain kinds of innovations, the innovations need to be measured, Edquist said. Ideally, he continued, innovation indicators must be comparative between countries and regions since there is no objective optimality. The Innovation Union Scoreboard (IUS, or European Innovation) is one such attempt to measure innovation.7 It is published every year and is intended to have an impact on policies. It includes 25 indicators that measure everything from R&D input to product innovation output. While recognizing its value in concept, Edquist identified a number of problems with the IUS, which claims to measure “EU Member States’ Innovation Performance” by calculating a Summary Innovation Index (SII).

Edquist claimed the SII fails to live up to its mandate, which he said means that it provides misleading information for politicians, policy makers, researchers, and the general public. The problem is that the index calculates a simple average of the 25 individual indicators, with each factor given the same weight. Among the indicators are both inputs, such as R&D expenditures, and outputs, such as actual product innovations. No distinction is made between them, which renders the underlying method akin to taking the average between the total production and the number of employees in a firm and calling it performance. In this sense, he said, the aggregate index has no meaning.

Given this methodological problem, Edquist and Zabala-Iturriagagoitia (2015) have worked on an alternative approach based on four input indicators and eight output indicators, using only IUS data. The input indicators refer to the resources (human, material, and financial; private as well as governmental) used to create innovations, including bringing them to the market. The output indicators refer to new products and processes, new designs and community trademarks, and marketing and organizational innovations, which are either new to the market and/or new to the firm and are adopted by users. Outputs are divided by inputs in order to calculate the efficiency of innovation systems at the national level.

The results from this calculation are very different from those derived using the SII. If nothing else, this shows the inherent arbitrariness of aggregate measures based on indicator scoreboards. If summary indicators are to be calculated, the conceptual and theoretical basis has to be clear, and Edquist noted that effort must be made to understand details

___________________

7See http://ec.europa.eu/growth/industry/innovation/facts-figures/scoreboards_en [August 2016].

driving the dynamics of innovation systems. Only then can policy instruments be selected to solve or mitigate the problems, he stated, that is, if the main causes of the problems are known.

Edquist turned next to innovation policy, which he argued is far behind innovation research. The failure of the interaction between research and policy suggests the need for “a holistic innovation policy,” defined as a policy that integrates all public actions that influence or may influence innovation processes in a coordinated manner. It includes actions by public organizations that unintentionally affect innovation and requires a broad view of innovation systems, including all of the determinants of the underlying processes. Edquist identified 10 important activities that are hypothetical determinants of the development and diffusion of innovations:

- R&D

- Education and training

- Formation of new product markets

- Articulation of quality requirements

- Creation and changing organizations

- Interactive learning

- Creating and changing institutions

- Incubation

- Financing of innovation processes

- Consultancy services

These activities also play a role in the public procurement of innovations. Edquist noted that total public procurement represents between 10 and 20 percent of gross domestic product in the European Union (around 2.3 trillion euros). This amounts to perhaps 40 to 50 times the size of the public R&D budget.

To analyze procurement demands, an assessment of what is bought in the public sector in functional terms (as opposed to products, goods, or services) is needed. In other words, policy makers should focus on the problems to be solved through innovation and spending rather than on products purchased. For addressing traffic noise in a neighborhood, for example, a local government should think in terms of buying a 1-decibel reduction in noise, not a specific item, such as a fence. The former encourages creative, competitive thinking about the effectiveness of alternatives, such as plantings, quieter road surfaces, or enforcement of slower speeds. This kind of procurement strategy is a powerful innovation policy instrument and, according to Edquist, it is starting to be used systematically by the Swedish National Innovation Council.

Kaye Husbands Fealing (Georgia Tech) continued the discussion

of innovation in nonmarket contexts, specifically as it applies to public health outcomes. She focused her comments on a study on food safety and security funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture as an example of innovation that directly affects public welfare.

The overarching question illustrated by her example, she said, is, “What are the social returns to public and private expenditures on science, technology, and innovation activities—and how can they be measured?” In the area of food safety, patents can be reviewed but, as argued by a number of participants in other contexts, this offers a highly truncated accounting of innovation. In the case of food safety sciences, new knowledge and innovations are often shared and not patented—they are not private goods. Additionally, the economic returns to federal (or other) government investments in food safety research (and other areas) cannot only be accounted for in terms of dollars and cents. Some of the value comes in the form of the development of new talent (as discussed by Stephan and others), and some will be the development of new ideas that spill over into other areas. For all of these reasons, she said, a broader measure (and indeed concept) of outputs of R&D is needed. If a goal is to have comprehensive measures of innovation inputs and outputs, particularly in the public sector, these are the kinds of factors that have to be assessed.

Husbands Fealing attached some figures to motivate the importance of food safety research. In 2011, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that 48 million cases of foodborne illnesses and infections led to 128,000 hospitalizations, 3,000 deaths, and $14.1 billion (in 2010 dollars) in economic burden. The CDC also estimates that one in six Americans is sickened by foodborne disease each year. She said this is a serious social problem that warrants investment in new knowledge and innovation on a regular basis, and the CDC identifies food safety as a “winnable battle” in the public health sector.8

Husbands Fealing noted that investment in research solves, or begins to solve, social and health problems, but few agreed-upon measures exist for assessing the value of this work. In the case of food safety, assessment involves tracking steps throughout the entire value chain from farm to table. With this goal, her research team is developing frameworks and techniques for measuring outcomes from federally funded research targeted at the agricultural sector in general and food safety in particular. The investigation has raised the following key questions:

- What expenditures have been made and how have these expenditures changed over time?

___________________

8See https://www.cdc.gov/winnablebattles/ [August 2016].

- Who is doing the research (principal investigators, graduate students, postdoctoral fellows, and staff scientists)?

- What kinds of jobs are taken by recent graduates trained in food safety? How do these early career activities relate to graduates’ career paths? What is the role of food safety research funding in graduate student training?

- What are the outputs of federally sponsored academic research? How are the results transmitted to the scientific and private sector, commercialized, and effective for the social good?

- What is the best method for funding research leading to the most significant breakthroughs?

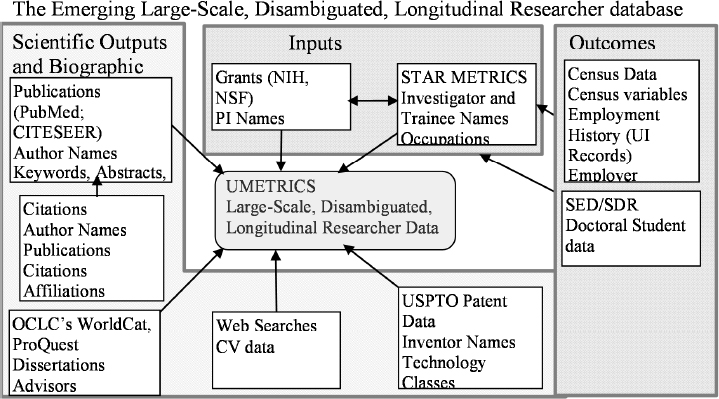

She said answering these research questions requires a coordinated data structure (as illustrated in Figure 5-1, which shows the emerging UMETRICS database linkages discussed earlier by Stephan). Such a structure should include project-level data (e.g., payroll records); natural language text analysis to identify food-safety research; and linkages among researchers, students, postdocs, patents, publications, dissertations, employment, and enterprises to be able to measure technology transfer.

SOURCE: Workshop presentation by Kaye Husbands Fealing, May 19, 2016; figure from Lane et al. (2014, p. 9).

Linking the data from these sources, the team can begin to see how much money is spent on food safety research and related activities over time. This involves not only general funding by the National Science Foundation in biology, but also a number of other fields and disciplines organized in a taxonomy designed to shed light on which grants actually relate to food safety and then tracing them through the system using all the data linkages shown in the figure.

Using the food safety example, Husbands Fealing demonstrated the possibilities of measuring the role of innovation for social goods. As in environmental, health, and other research areas, she said, there is a lot of policy value to be gained from improving assessments of the return—the social benefit—from such funding on science.

HOUSEHOLD-SECTOR INNOVATION

Continuing with the theme of nonmarket production, Eric von Hippel (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) discussed household-sector innovation and made the case for why it should be measured. He noted that household-sector innovation is quantitatively very large but is not currently being measured; many activities are not even defined as innovation because the outputs are diffused for free. He also said not measuring household-sector innovation creates distortions in public policy discussions that determine what governments choose to do.

By way of background, von Hippel noted that, in economics, consumers are traditionally viewed as passive users of producer-developed products and services, and not as developers themselves (Schumpeter, 1934). In reality, however, as revealed by nationally representative time use and other kinds of surveys, an enormous amount of innovation originates from the household sector. Eliminating certain activities (e.g., those resulting in little functional novelty), von Hippel et al. (2010) found that 6.1 percent of the UK population innovated within the past 3 years, developing or improving a product for themselves (the numbers are comparable, but slightly lower for the United States). This amounts to 2.9 million people engaged in such activities, whereas in the entire United Kingdom only 22,300 R&D professionals work on developing products for consumers. The amount that households are spending is not measured at all. Inferring from the above statistics, however, it is reasonable to suspect that the level of household expenditures on innovative activities is not very different from the amount that firms are spending on R&D.9

___________________

9Workshop participant Jeff Oldham (Google) ran a Google Consumer Survey overnight between the days of the workshop that asked, “Did you improve or create a product or process in your free time during the past year?” Twenty percent of the more than 900 respondents

Next, von Hippel provided several examples of household-sector innovation. The Ushahidi Crisis Map service in Haiti was a very important reporting tool for providing free disaster information during the 2010 Haitian earthquake. It was developed in the household sector using the Ushahidi open-source software to post information about friends’ and relatives’ whereabouts.10 In the medical sector, two people developed an artificial pancreas ahead of medical producers and diffused their design for free through the Nightscout Foundation. (This work involved creating predictive software that provides real-time recommendations for insulin and embedding the software in a closed-loop device to deliver the recommended doses.)11 Market-based producers will follow after approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

The policy question that arises is whether these kinds of innovations can be nurtured as opposed to quelled. Is it possible, von Hippel asked, to equip individuals and households with clinical trial software so that they can engage in grassroots innovation processes themselves? Are FDA regulations set at the right levels of stringency? Just as intellectual property (IP) enhances innovation by producers, it is important to think about public support for enhancing diffusion among household-sector innovators. These, he said, are policy choices.

Turning to a possible measurement strategy, von Hippel identified two elements in the definition of a “free” innovation: (1) it is developed at private cost by individuals during their unpaid leisure time and (2) design information is unprotected by the developer and potentially acquirable by anyone “for free,” representing a kind of market failure. This means that there are no transactions during the process that can be tracked by ordinary economic measures (e.g., sales or patents). Another characteristic is that less than 10 percent of these individuals try to protect their innovations, and they rarely spend much time diffusing them. As a result, IP is not a central feature of this system.

The above-described types of innovation are not measured at all in official statistics. One reason is that free innovation does not fit the Oslo Manual definition of an innovation, described earlier. The consequence is that a free innovation—even one diffused millions of times for free over the Internet—conforms to the definition only if it is introduced to the market. Even then, it is credited to the producer that commercialized it, not the person who developed it. As a result, estimates of the effective-

___________________

who replied over the 12-hour period prior to day 2 of the workshop said that they had innovated during the past year.

10See https://www.ushahidi.com/ [August 2016].

11See https://diyps.org/, and http://www.nightscoutfoundation.org/about/ [August 2016].

ness of producer R&D and the apparent importance of IP are overstated. Meanwhile, free innovation is understated, and free innovators, who are often innovation pioneers, are undercounted. The distortions created by not measuring free innovation, von Hippel argued, carry policy implications. In order to correct for this weakness in the innovation measurement system, von Hippel proposed that social surveys are needed to supplement business surveys such as the CIS.

Working with colleagues Alfonso Gambardella and Christina Raasch, von Hippel showed that free innovation increases social welfare (Gambardella et al., 2015). Because free innovation competes with producer innovation, prices may be lowered—for example, when the Linux operating system is provided for free. Free innovations are also a source of supply designs and free complements. Also, there are many things that producers make that require complements that are only provided for free, because there is no market for them. Product users—who are often early but invisible innovators—frequently play this role. Von Hippel gave the example of mountain bicycles. Mountain biking techniques are not developed in a commercial market; they are diffused peer to peer in a way that is detached from producers. Producers benefit because technique innovators increase the value of mountain bikes and may increase sales. Von Hippel and his colleagues also studied whitewater kayaking and discovered that, over 50 years, among 100 of the most important innovations, 80 percent were introduced by the users of kayaks and picked up for free by the producers (Hienerth et al., 2012). If producers had had to develop all these designs, their budgets for R&D would have needed to be three times larger. These processes take place throughout the economy—this kind of feedback is common with scientific and medical instruments, for example.

Von Hippel concluded by offering some guidance to NCSES, other statistical agencies, and OECD. He urged that the Oslo Manual include nonmarket diffusion. Its exclusion from the definition is a barrier to recognizing that activities taking place beyond the market can be innovations. This is the gateway problem, he said. Myopic focus on the market is an outdated way of thinking, reflecting a time when the market was the dominant mechanism for diffusing things. In an Internet-based world, free diffusion is prominent and should be reflected in new measurement guidelines.

In open discussion, Ben Martin said he largely agreed with this view, but he added qualifications about the intrinsic limits of indicators. He agreed that the scope of indicators should be extended to cover a wider range of innovations, but he expressed concern about Gault’s proposal to change the wording in the Oslo Manual definition from “improved” to “changed.” He cautioned that, whether in the market or nonmarket context, there could be a danger of bringing in incremental product

changes that do not have an impact on economic or social outcomes and well-being.

Gault responded that measurement is something that should be pursued with as few normative terms as possible. If a new financial product based on subprime mortgages has been produced and put on the market, for example, innovation measures should capture this. That the product is then diffused and goes on to harm the economy is exposed only after the fact through normative assessment. It is not so clear that the assessment itself should be part of the innovation indicator system, he said, as opposed to being the subject of subsequent research measuring the outcomes associated with the innovation.