C

Ebola Virus Disease Preparedness

in Germany: Expertise Focused in

Specialized Laboratories, Competence,

and Treatment Centers

Reinhard Burger1 and Lars Schaade2

In the last decade, emerging or reemerging infectious pathogens have been posing a serious threat to human health almost every year. Highly infectious and pathogenic agents, frequently zoonotic pathogens, have turned out to be a public health threat for the human population and to cause unexpected outbreaks. Countries need to be prepared and to cope with the challenge of emerging or reemerging highly pathogenic infectious agents in a reliable and safe fashion.

In Germany, a concept for the management of highly contagious and life-threatening diseases such as Ebola virus disease (EVD) is in place. There are three key components:

- A network called STAKOB (Ständiger Arbeitskreis der Kompetenz-und Behandlungszentren für hochkontagiöse und lebensbedrohliche Erkrankungen)3 consisting of public health authorities (competence centers) and high-level isolation units (treatment centers) specialized in handling these diseases. It provides special expertise for patient care, clinical diagnostics, and additional infection control measures, thereby facilitating an efficient response.

- Profound expertise in crisis planning and provision of information on preparedness and response measures for the professional audience, public health authorities, and decision makers, coordinated by a specialized

___________________

1 Robert Koch Institute, Nordufer 20, 13353 Berlin, Germany (BurgerR@rki.de).

2 Robert Koch Institute, Nordufer 20, 13353 Berlin, Germany (SchaadeL@rki.de).

3 Acronym of Ständiger Arbeitskreis Kompetenz-und Behandlungszentren, Permanent Working Group Competence and Treatment Centers.

-

Center for Biological Threats and Special Pathogens at the Robert Koch Institute (RKI).

- A well-functioning public health sector with local health authorities being able early to detect and report highly contagious diseases in order to assure adequate clinical management of these cases and the necessary infection prevention and control measures.

Generic preparations on all levels should already be in place to be best prepared for future threats posed by highly pathogenic agents and to assure early detection, profound situation assessment, and execution of public health measures to provide the optimal medical care and avoid spread of the disease.

THE 2014 EBOLA OUTBREAK IN WEST AFRICA

The present outbreak of EVD in West Africa has been affecting, as of July 2015, three countries with widespread and intense transmission. Seven countries have reported imported EVD cases, a few of which caused limited local transmissions (WHO Ebola Response Team, 2014). It is the largest EVD outbreak in history, with more than 27,000 cases and 11,000 deaths, and new EVD cases are still being confirmed every week. Previous outbreaks had been much more limited in terms of cases and geographic spread (Briand et al., 2014; Chan, 2014; Chertow et al., 2014).

The 2014 EVD outbreak in West Africa is caused by Zaire Ebola virus of the Filoviridae family. The virus was transmitted to a human from wild animals and has been spreading since in the human population through direct contact with symptomatic patients or deceased EVD cases, via contact with blood, secretions, organs, or other bodily fluids of infected people or through exposure to objects contaminated with these fluids (Feldmann, 2014; Feldmann et al., 2003; Gire et al., 2014; Schieffelin et al., 2014; Wolf et al., 2014).

The risk of transmission correlates with a higher level of viremia. It is considered to be higher in a later stage of EVD compared to the initial stage of the disease. After clearance of viremia, live Ebola virus has still been isolated in seminal fluids and ocular fluid in convalescent men (Mackay and Arden, 2015; Varkey et al., 2015). Amniotic fluid in pregnant women was polymerase chain reaction (PCR) positive for Ebola virus upon clinical recovery (Baggi et al., 2014).

THE COMMITMENT OF RKI IN WEST AFRICA

The most effective measure to protect Germany from imported EVD cases is the support of West African countries in their fight against EVD. Of high importance are local support in identifying infectious patients, building a reliable surveillance system, establishing proper clinical case management, improving

laboratory diagnostics, and strengthening infection prevention and control in health care in the affected area and beyond.

RKI is strongly committed to several activities in the affected and neighboring countries:

- Field epidemiologists from RKI have supported the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network in case investigation, contact tracing and active surveillance.

- Laboratory expert staff has been sent already very early on to European Mobile Laboratories in the affected countries to strengthen Ebola virus laboratory diagnostic capacities (Carroll et al., 2015).

- Virologists have investigated the zoonotic origins of the epidemic using wildlife surveys, interviews, and molecular analyses of bat and environmental samples (Marí Saéz et al., 2014).

- Experts in clinical management have developed a training program for health-care facilities in neighboring countries at risk to be able to detect and care for suspected cases of EVD until relocation to a treatment center is possible.

- Laboratory experts have established a diagnostic laboratory in Côte d’Ivoire and have trained local staff in Ebola virus diagnostics.

LIKELIHOOD OF EVD CASES IN GERMANY

The likelihood of an imported EVD case in Germany has been assessed to be very low since the beginning of the EVD outbreak in West Africa. It cannot be excluded that in isolated instances a person travels to European countries while incubating the infection and without obvious symptoms. Such a case could develop EVD in Germany and could possibly lead to a limited number of secondary infections. Further widespread transmission of the Ebola virus within the German population appears to be practically impossible, even in light of a few imported hypothetical infections. Germany fulfils all prerequisites to break the chain of transmission effectively and to care safely for those affected. Therefore, no risk for the general population beyond individual cases is anticipated.

In the following, the preparedness measures are summarized regarding infection prevention and control as well as clinical management of EVD cases in Germany.

CRITICAL ELEMENTS OF PREPAREDNESS

Exit screening of travelers in affected West African countries provides a helpful element, if sensitive screening procedures are available. Effective exit screening removes the need for entry screening.

A thorough assessment of any suspicion of EVD is necessary, though it is clinically complicated to rule out other tropical diseases, particularly malaria, because of the nonspecificity of early EVD symptoms. Taking a comprehensive travel and exposure history is critical. Laboratory diagnostic procedures must be in place to identify a positive EVD case quickly.

In addition, differential diagnoses must be assessed to avoid therapy delays for other potentially life-threatening diseases, such as malaria, and to prevent false alarms with far-reaching consequences. As no specific therapy is available at the time of writing this paper, patients suffering from EVD are treated mainly symptomatically, which should be rooted in as much evidence as possible. Providers can offer to administer experimental therapeutics to patients on a case-by-case basis (Reardon, 2014).

All measures to be taken must consider that the capacity of the public health system and of specialists familiar with laboratory detection of Ebola virus and with the management of EVD cases is limited. Therefore, it is of utmost importance to avoid noneffective or unnecessary activities that would otherwise block medically necessary care, human resources, or laboratory capacity.

Clear information on the animal reservoir and the exact mode of transmission from animal to human contacts would be helpful. The same is true for the exact mode of transmission from human to human and the identification of risk factors (Judson et al., 2015; Marí Saéz et al., 2014; Ryan and Walsh, 2011; Vogel, 2014).

Considering the enormous media attention, efficient communication strategies are necessary. They should be able to raise awareness in a sufficient and adequate fashion without creating nonjustified fear or even occasionally panic.

Coordination of all these activities is particularly important, especially in a federal system like Germany where the federal government and federal institutions work together with 16 states (Länder) and the corresponding state and local health authorities (up to 400 counties).

PREPAREDNESS PLANNING IN GERMANY FOR EVD CASES

RKI, as the German national public health institute, has developed a number of guidance documents relating to EVD, the most comprehensive of which is Framework Ebola Virus Disease (RKI, 2015).

This framework is designed to summarize all available information, recommendations, and regulations regarding infection control and clinical management of EVD cases in Germany as of 2015, in response to the outbreak in West Africa. Issues across the spectrum of diagnostics, treatment, contact person management, personal protective equipment (PPE), disinfection, disposal of waste, and management of wastewater, are addressed. The framework was developed in cooperation with several stakeholders: federal and state health authorities, the Committee for Biological Agents, the German Society for Infectious Diseases, the German Society for Tropical Medicine, the German Society for Hygiene and

Microbiology, the Society for Virology, the German Association for the Control of Virus Diseases, the Paul Ehrlich Institute, the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices, the Permanent Working Group of Medical Competence and Treatment Centers for highly contagious, life-threatening diseases (STAKOB), the National Reference Center for Tropical Infections at the Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine–Hamburg, and the National Consultant Laboratory for Filoviruses at the Institute of Virology at Marburg University.

The document is primarily intended for public health authorities and health care workers in German hospitals, outpatient clinics, and emergency services to facilitate the detection, evaluation, and management of suspected and confirmed EVD cases in Germany.

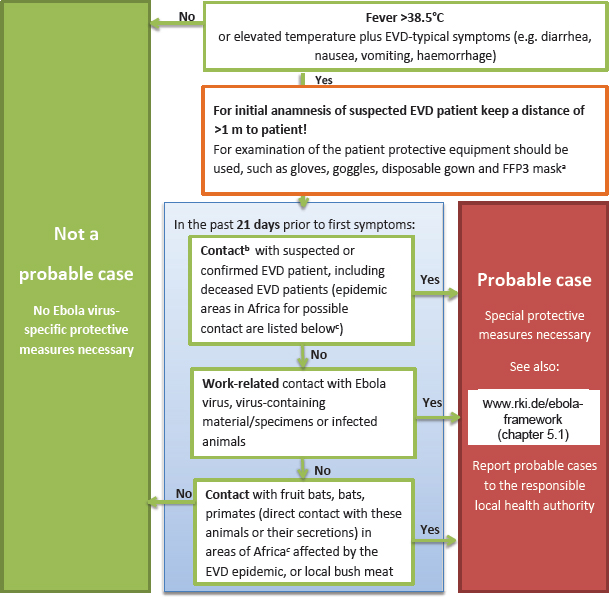

One of the most frequently cited elements of the EVD framework is a flowchart with specific advice for physicians/clinicians in Germany to help recognize probable cases of EVD if there is an initial suspicion for EVD (see next section, “Recognizing a Probable Case of EVD”). The earlier a probable EVD case can be assessed and infection control measures applied, the higher the chance to completely prevent secondary infections, or at least limit their numbers.

RECOGNIZING A PROBABLE CASE OF EVD

Clear-cut and reliable criteria defining a well-founded suspicion (“probable case”) of EVD are essential for avoiding unnecessary alarm or any delay in necessary medical care and for protecting the laboratory and clinical capacity from an unjustified burden of work. This is particularly true since the initial symptoms of EVD are rather nonspecific.

Early symptoms like sudden onset of fever, fatigue, muscle pain, headache, and sore throat or even later symptoms like vomiting, diarrhea, rash, and bleeding can also occur in a number of other diseases. Thus, clinical symptoms represent only one element in defining a probable case of EVD, and additional criteria have to be included.

According to the framework, a probable EVD case is defined when a patient with fever (> 38.5°C) or elevated temperature combined with other symptoms (e.g., diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, or bleeding) also fulfills one of the following two critieria:

- Contact history with a known EVD patient within 21 days before onset of symptoms. Here the term EVD patient also includes patients who are suspected of having EVD or who died of EVD. The contact history would also apply to persons who in the 21 days before symptom onset have worked with Ebola virus, Ebola virus–containing materials, or Ebola virus–infected animals in a laboratory or any other institution.

- Travel history for the last 21 days if the patient spent time in a known Ebola virus–endemic area (country reporting cases repeatedly in the past)

or in an area that recently reported EVD cases for the first time, and if the patient had contact to fruit bats, other bats, or nonhuman primates (e.g., as bush meat or direct contact with live animals or their feces) (RKI, 2015).

The flowchart (see Figure C-1) aiding in the assessment of these criteria has provided helpful guidance for clinicians. It was published online and in the weekly and widely distributed journal of the German Medical Association, making it available to all physicians.

These clear criteria helped dramatically to reduce unnecessary alarm. The flowchart can be found on the RKI website.4

___________________

4 See http://www.rki.de/EN/Content/Prevention/Ebola_virus_disease/Flowchart_Ebola.pdf?__blob=publicationFile (accessed November 3, 2016).

NOTE: EVD = Ebola virus disease; FFP3 = filtering face piece, model 3.

- The listed occupational safety measures are recommended by the Committee for Biological Agents (ABAS) of the Federal Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (BAuA). Instructions on protective equipment can be found in Framework Ebola Virus Disease, Chapter 5.1, at http://www.rki.de/ebola-framework (accessed November 3, 2016). Instructions for disinfection can be found at http://www.wki.de/ebola-disinfection (accessed November 3, 2016).

- Contact:

- Direct contact with blood or other body fluids (including virus-containing tissue) of confirmed or deceased or probable EVD patients, as well as possible contact with Ebola virus–contaminated clothing/objects.

- Unprotected contact (distance of < 1 m) with confirmed or deceased or probable EVD patient, including household contacts, flight passengers (one seat in all directions and across the aisle) and flight crew members attending the patient.

- Visit to an African hospital potentially treating EVD patients.

No contact: Presence (distance of > 1 m from a patient) in the same room/transportation vehicle.

- Areas currently affected are mentioned in the WHO situation reports accessible at http://apps.who.int/ebola/ebola-situation-reports (accessed November 3, 2016).

SOURCE: http://www.rki.de/ebola-framework (accessed November 3, 2016).

MEASURES IN THE EVENT OF A PROBABLE CASE

If a probable EVD case has been identified measures have to be taken in a whole range of areas by the physician, local hospital, local health authority, or competence and treatment center.

The main goal is to transfer the patient safely and as soon as possible into a special isolation unit of a treatment center for further diagnostics and appropriate treatment. The assumption is that the patient stays as briefly as possible on the site where he or she has been identified, with only essential procedures involving physical contact to be conducted prior to transfer to an isolation unit.

For primary care of a probable EVD patient, the framework outlined that he following minimum PPE ought to be available:

- Respirator: FFP3 mask.5

- Eye and face protection: Protective goggles like those used in endoscopic practices and a face shield.

- Hand protection: Two pairs of liquid-proof gloves with protection against mechanical and biological risks. Gloves should have cuffs to ensure a sufficient overlap with the clothing mentioned below.

- Body protection: Liquid-tight material allowing for safe doffing. Disposable suits category III, type 3B,6 are recommended in combination with a disposable plastic apron. Disposable suits ought to have a hood. Hoodless suits are to be complemented with a separate shoulder-length hood.

- Foot protection with disposable overboots of liquid-proof material or rubber boots. (RKI, 2015)

A great deal of emphasis is placed on the question of whether appropriate PPE is available and whether sufficient training is performed on how to don and doff it adequately.

A critical step is the disposal of contaminated PPE. Disposal should only be performed after proper disinfection. In the case of a confirmed EVD patient, full-body decontamination must be performed before disposal of PPE. The doffing of the protective clothing and decontamination must be done in the buddy system, meaning with the help of a second person. It cannot be emphasized enough that only correct donning and doffing of PPE guarantees protection of the person. Only instructed and trained personnel should perform care for probable and confirmed cases of EVD. Such treatment should strive to minimize contact, particularly for invasive procedures performed outside of high-level isolation units, which must be reduced to the absolute minimum required. Complying with basic protective procedures, including hygienic standards and safe waste management (including both solid and liquid waste) are mandatory.

Confirmation or exclusion of Ebola virus by laboratory diagnostics is an important next step to distinguish suspect cases from true EVD patients. Ebola virus is categorized as a biosafety level (BSL)-4 pathogen. Handling of this virus requires special containment facilities and barrier protection. Only if urgently needed should samples be taken outside of a high-level isolation unit and only after consultation with the local public health authority and the responsible competence and treatment center. Primary orientation diagnostics are performed in a BSL-4 laboratory (or in an appropriate BSL-3 laboratory) by molecular methods.

Routine and differential laboratory diagnostics are performed preferentially as point-of-care diagnostics in the treatment center. Should a suspect case of EVD require routine laboratory diagnostics (e.g., clinical chemistry) and specific laboratory tests for differential diagnosis (e.g., for malaria) before being transferred

___________________

5 FFP3, filtering facepiece, model 3. This respirator provides the highest form of protection for the wearer.

6 These models of disposable PPE confer the highest disaster protection.

to a hospital specialized in patients with highly contagious infections (treatment centers), the Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine in Hamburg or one of the treatment centers should be contacted in order to decide the best course of action.

A probable EVD case has to be notified according to the Infection Protection Act (Infektionsschutzgesetz). The follow-up of contact persons is important for preventing further spread of the disease. Release of contacts should only occur in agreement with the local health authorities. Documentation of the details of each contact person and the corresponding classification of the exposure risk are important.

Waste contaminated with Ebola virus should be inactivated in the place where it occurs according to the strict regulations specified by the Federal/State Waste Committee. If this is not possible the waste has to be burned in a special waste incineration plant approved for waste with waste code 180103. The waste must be packed in accordance with the United Nations treaty that governs transnational transport of hazardous materials (the European Agreement concerning the International Carriage of Dangerous Goods by Road) when transported to the special incineration plant—for larger amounts of waste according to the multilateral agreement M281 of member states of the European Union.

Wastewater including feces and urine of a probable EVD case can be discarded in a separately used toilet due to the low level of virus shedding and the dilution effect. Wastewater including feces and urine, which is generated during care for a confirmed case of EVD, has to be disinfected or inactivated.

Disinfection of contaminated surfaces needs to be done with approved disinfectants from the RKI disinfection list or the list by the Association for Applied Hygiene.7

PERMANENT WORKING GROUP OF COMPETENCE AND TREATMENT CENTERS

In 2000 a national concept for the management and control of highly contagious life-threatening infectious diseases was established in Germany in order to be prepared for imported serious infections that might pose a threat to public health, including viral hemorrhagic fevers and other highly infectious life-threatening diseases, most of them caused by BSL-4 pathogens.

A key element of this concept is a network called STAKOB (Gottschalk et al., 2009). Since 2014, it is a permanent working group of public health authorities (competence centers) and high-level isolation units (treatment centers) for highly contagious and life-threatening diseases, coordinated by RKI. The permanent working group combines clinical and public health experts together with

___________________

7 See http://www.ihph.de/vah-online/uploads/PDF/PrefaceVAHList.pdf (accessed November 3, 2016).

external ones from the national reference and national consultant laboratories, the Committee for Biological Substances, the tropical medicine department of a military hospital, the Commission for Hospital Hygiene and Infection Control, the Federal Institutes for Drugs and Medical Devices (BfArM) and Vaccines (Paul Ehrlich Institute), and the Federal Foreign Office.

The treatment centers with their high-level isolation units gather specialized medical knowledge in infectious diseases, including highly contagious and potentially life-threatening ones, as well as skills in their clinical management, diagnosis, and hygiene management. They ensure that all infection-prone steps are performed only by well-trained, highly specialized medical personnel. All network members have the proper technical equipment and facilities available. Staff is voluntarily involved. Exercises simulating events are held at least once every 6 months. Some institutions hold these simulations more frequently. All treatment centers operate along comparable standards. This guarantees a quick and professional reaction, also in critical situations. In addition, orientation along similar standards allows the rapid exchange of personnel between different centers if needed. Most hospitals use their treatment centers in normal times, outside of crises, for patients with other infectious diseases, such as multidrug-resistant tuberculosis cases, due to economic considerations.

The competence centers are based in the federal states and operate within the German public health service (Öffentlicher Gesundheitsdienst, ÖGD). They provide advice by telephone and onsite support for local public health authorities, doctors, and hospitals in the center’s area of responsibility. They obtain and forward up-to-date epidemiological information; provide support regarding diagnostics in consultation with the diagnostic center; provide decision-making assistance on the isolation, referral, or transfer to the treatment center; and organize the logistics with specialized ambulances. In the case of an outbreak of a highly contagious and life-threatening disease, they coordinate antiepidemic measures. They provide detailed guidelines on the management of contacts, such as the identification, risk evaluation, and monitoring of contacts. Risk and crisis communication strategies are also discussed between the competence centers.

STAKOB training centers ensure through their training efforts both the successful management of highly contagious patients and the safety of the medical staff. They also train external staff. Trainings are carried out by infectious diseases specialists. The first training program was developed by the Medical Mission Hospital (Missionsärztliche Klinik) in Würzburg. In addition to Würzburg, corresponding training courses with different focuses are offered in Leipzig, Hamburg, and Berlin (RKI, AMBIT courses).

At present, there are seven competence centers (Berlin, Frankfurt, Hamburg, Leipzig, Munich, Münster, and Stuttgart) and seven treatment centers (Berlin, Düsseldorf, Frankfurt, Hamburg, Leipzig, Munich, and Stuttgart). They are distributed over Germany to avoid long transportation times.

EXPERIENCE OF THE STAKOB TREATMENT CENTERS WITH EVD CASES

The treatment centers have been planned with a maximum capacity of approximately 50 beds. It must be emphasized that not all beds could be used at the same time, and only a smaller number are intensive care beds. Experience with the EVD cases showed that, for a single patient, medical staff of up to 30 health care workers is required (Kreuels et al., 2014). Because of the constraints of wearing PPE, health care workers have to work in several shifts, with each person staying in the isolation ward for a maximum of about 4 hours on each shift.

The direct and particularly the indirect costs (e.g., loss of regular patients or need to replace staff) are enormous when treating a patient. Most of the time, personnel has to be withdrawn from other wards, which therefore could cease to be functional.

Our experience also showed that the storage of sufficient material is important. With a large number of personnel the consumption of single-use disposable items and the corresponding creation of waste are enormous.

MEDICAL EVACUATION AND TREATMENT OF INTERNATIONAL HEALTH CARE WORKERS

During this ongoing outbreak, a number of health care workers have been accidentally exposed to biological samples or had direct contact with patients without proper personal protection. Some of them were flown out for treatment to either European countries (France, Germany, Italy, Norway, Spain, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom) or the United States.

After intensive discussions, the German government decided that expert staff sent into the outbreak area would be guaranteed a medical evacuation for treatment in Germany in the case of an Ebola virus infection. All decision makers felt it to be ethically necessary to provide health care workers with the chance to be repatriated in case there was a need for appropriate medical treatment. Preferentially such repatriation by airplane should also allow for medical care onboard, including intensive care. Some transport solutions commercially available so far for highly contagious patients do not allow performing procedures on a symptomatic patient, such as infusion or treatment of patients vomiting or with diarrhea.

The German Federal Foreign Office has led a project to transform a civil airplane into a kind of ambulance airplane to safely transport and treat EVD patients onboard. Plans were made for a high-level isolation unit installed within the airplane, allowing direct access to the patient and medical treatment. The reconstructed airplane contains a chambered plastic tent creating a mobile high-level isolation unit following almost the same standards as the high-level isolation units in treatment centers in Germany (see Figure C-2).

According to the protection concept, this built-in plastic tent contains outer and inner locks, and a third chamber is the patient unit with equipment used for

SOURCE: Copyright by Nordwest-Box GmbH & Co KG, Wardenburg, Germany © 2014, with permission.

intensive care. It also contains facilities for waste management and was suitable for final disinfection procedures. A device was invented by Lufthansa suitable to take up pressure and prevent air leakage from the high-level isolation unit in case of unexpected loss of pressure in the cabin. The design was made to transport one patient at a time.

The plans for the MedEvac were finalized within a few weeks and the three-chambered unit was constructed and tested by the responsible project partners. The local authority responsible for occupational health in Hamburg gave permission to use the airplane with the high-level isolation unit onboard. In a ceremony together with Federal Foreign Minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier, Federal Minister of Health Hermann Gröhe, and the first author of this article in his function as president of RKI, the airplane was handed over and christened Robert Koch.

The availability of this airplane was widely welcomed in the media as a kind of precautionary step, comparable to fire insurance.

RESPONSIBILITY OF A NATIONAL PUBLIC HEALTH INSTITUTE IN A FEDERAL SYSTEM

The preparation for potentially imported EVD cases revealed the “splendor and misery” of a federal system. The responsibilities are split between federal institutions (Federal Ministry of Health, RKI, etc.) and the federal states with their respective public health authorities all the way down to the local level.

In the German federal system, the responsibility on an operational level in the event of an imported case of EVD stays within each state. Contrary to general assumptions, federal institutions like RKI cannot legally order the states to implement certain recommendations or procedures. The institute has no mandate on the operational level. Health authorities of the states are capable of managing outbreaks of infectious diseases on a local level, and RKI gives support if requested, such as in outbreak investigations. In times of crisis, there is an intensive and rapid exchange of information, often independent of the formal lines of communication.

If rare, highly infectious and pathogenic agents are involved, the state and local health authorities appreciate additional support by providing information on the management of these diseases. During the 2014 Ebola outbreak, RKI gave extensive advice on early detection of probable EVD cases, infection prevention, and control measures as well as on the clinical management of EVD cases. The local health authorities played an important role in the preparation for EVD cases in Germany and readily accepted all kinds of recommendations and guidelines from RKI.

The specialized Centre for Biological Threats and Special Pathogens at RKI has proven to be irreplaceable in strengthening national public health preparedness and response capabilities in such an event. The Federal Information Centre for Biological Threats and Special Pathogens quickly produced critically

important information on all relevant public health topics, involving experts from all departments of RKI. Advice was given around the clock to decision makers and the professional public. Training courses in advanced management of unusual biological threats are conducted regularly by RKI for local public health authorities.

Coordination of all relevant partners in an acute crisis is challenging. During the Ebola crisis, RKI cooperated with state and local health authorities and numerous scientific societies.

It was of great value that specialized institutes (Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine in Hamburg, Institute of Virology in Marburg, and RKI in Berlin) and the STAKOB competence and treatment centers were available 24 hours a day for enquiries concerning highly contagious diseases.

In times of crises, not only medical professionals but also the general public expect information rapidly on recent developments. RKI provided information via the Internet, particularly via continuously updated frequently asked questions, and gave specific recommendations according to the most recent developments. Updates of these recommendations were made available in the journal provided to all German physicians (Deutsches Ärzteblatt, a journal appearing weekly) and also the weekly Epidemiological Bulletin of RKI, mainly addressing the public health service.

It has become obvious that the reduction of personnel in the public health service during the past decade has turned into a major obstacle. Some local health authorities are left with only a limited number of staff. In the discussions and preparations in Germany during this Ebola outbreak in West Africa, the importance of a functional public health system became evident repeatedly; outbreaks like severe acute respiratory syndrome, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), or Ebola virus reveal its critical role. Rapid reporting of notifiable infections should be strengthened.

While the above-mentioned treatment centers were revealed to have sufficient bed capacities and were well equipped and advanced in terms of both biosafety standards and treatment strategies, a gap between those centers and the periphery cannot be denied. Each of the seven treatment centers is responsible for coverage of 1 to 5 of the 16 states (Länder). Patients arriving with infectious diseases that mimic a highly contagious and life-threatening disease (e.g., severe malaria, a common, potentially life-threatening and easily treatable differential diagnosis of EVD) at a hospital other than a specialized treatment center can become a challenge. In turn, patients with highly contagious and potentially life-threatening diseases could arrive, although not likely, at any place and any time as imported cases. Other BSL-3 (e.g., MERS-CoV, multidrug-resistant- and extensively drug-resistant-Mycobacterium tuberculosis) or BSL-4 (e.g., Marburg virus, Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever virus) pathogens beyond the West African Ebola outbreak should not be forgotten.

Transporting a patient with an infectious disease by ambulance from one place to another can be strenuous, depending on the clinical condition of the patient. Training needs for primary, secondary, and even highly specialized tertiary health care facilities became evident.

Hence suitable tertiary health care facilities should be strengthened in their capacity to temporarily isolate a patient, handle PPE, and provide the first necessary diagnostic and therapeutic measures, including antimalarial treatment, if required. These facilities should be identified and trained accordingly by treatment centers, which would, however, require financial and human resources support for both actors. Coverage on the local level should be complemented by an “infectious diseases casualty doctor,” meaning a doctor trained both in emergency medicine and infectious diseases who could reach the periphery—a home or health center—in the event of clinical suspicion of a highly contagious and potentially life-threatening disease.

EXPECTATIONS OF PUBLIC HEALTH INSTITUTIONS DURING AN EVD OUTBREAK

The European national public health institutes were confronted with numerous questions and demands from almost all professional circles, including domestic and international aspects. The contribution of a public health institute domestically includes a solid risk assessment, reliable and rapid counseling of decision makers in health politics, risk and crisis communication, technical advice and support in many practical aspects for hospitals and public health service, detailed instructions for safe and reliable diagnostic services, and finally interventional epidemiology in the case of suspected transmission incidents.

National public health institutes are also challenged internationally with numerous requests. RKI has been asked for advice on the administrative level by German federal and state ministries, but also for technical assistance and diagnostic support by neighboring countries. In addition, technical and scientific support in the West African countries affected by the outbreak was requested. An important contribution was the transfer of technology and knowledge in order to help the local health system to perform surveillance and diagnostics independent of external experts. This type of capacity building was usually focused on diagnostic services but also went far beyond, such as contact tracing and other interventional epidemiological and management support.

Frequently, the limits of a national public health institute became obvious. Some demands could not be fulfilled because they were beyond the operational capacity or scope of a national institute and required support from large charitable organizations, the military, or other logistically prepared institutions such as Médecins Sans Frontières. Such requests included the establishment and operation of treatment centers, the logistic support of treatment, and the allocation of suitable financial resources for operation on the local level. Social mobilization

of the local population concerning infection control also requires local organizations familiar with the behavior and customs of the population. Finally, a foreign national public health institute is unable to implement public health measures in another country.

Further details of the activities of RKI are available on the website of the institute: www.rki.de. The recommendations of the framework EVD are also available online: http://www.rki.de/EN/Content/Prevention/Ebola_virus_disease/Framework_EVD.html (accessed November 3, 2016).

In retrospect, we feel it is prudent of any public health institute to learn as much as possible from such outbreaks in order to be prepared for future events. Soon after a crisis there should be an analysis with all major stakeholders to define the lessons learned (Frieden et al., 2014; Gates, 2015; Heymann, 2014; Spencer, 2015).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank Dr. Christian Herzog, Dr. Iris Hunger, and Dr. Thomas Kratz for helpful comments, and Ms. Ursula Erikli for careful preparation of the text.

REFERENCES

Baggi, F. M., A. Taybi, A. Kurth, M. Van Herp, A. Di Caro, R. Wolfel, S. Gunther, T. Decroo, H. Declerck, and S. Jonckheere. 2014. Management of pregnant women infected with Ebola virus in a treatment centre in Guinea, June 2014. Euro Surveill 19(49):pii-20983.

Briand, S., E. Bertherat, P. Cox, P. Formenty, M. P. Kieny, J. K. Myhre, C. Roth, N. Shindo, and C. Dye. 2014. The international Ebola emergency. N Engl J Med 371(13):1180-1183.

Carroll, M. W., D. A. Matthews, J. A. Hiscox, M. J. Elmore, G. Pollakis, A. Rambaut, R. Hewson, I. Garcia-Dorival, J. A. Bore, R. Koundouno, S. Abdellati, B. Afrough, J. Aiyepada, P. Akhilomen, D. Asogun, B. Atkinson, M. Badusche, A. Bah, S. Bate, J. Baumann, D. Becker, B. BeckerZiaja, A. Bocquin, B. Borremans, A. Bosworth, J. P. Boettcher, A. Cannas, F. Carletti, C. Castilletti, S. Clark, F. Colavita, S. Diederich, A. Donatus, S. Duraffour, D. Ehichioya, H. Ellerbrok, M. D. Fernandez-Garcia, A. Fizet, E. Fleischmann, S. Gryseels, A. Hermelink, J. Hinzmann, U. Hopf-Guevara, Y. Ighodalo, L. Jameson, A. Kelterbaum, Z. Kis, S. Kloth, C. Kohl, M. Korva, A. Kraus, E. Kuisma, A. Kurth, B. Liedigk, C. H. Logue, A. Ludtke, P. Maes, J. McCowen, S. Mely, M. Mertens, S. Meschi, B. Meyer, J. Michel, P. Molkenthin, C. Munoz-Fontela, D. Muth, E. N. Newman, D. Ngabo, L. Oestereich, J. Okosun, T. Olokor, R. Omiunu, E. Omomoh, E. Pallasch, B. Palyi, J. Portmann, T. Pottage, C. Pratt, S. Priesnitz, S. Quartu, J. Rappe, J. Repits, M. Richter, M. Rudolf, A. Sachse, K. M. Schmidt, G. Schudt, T. Strecker, R. Thom, S. Thomas, E. Tobin, H. Tolley, J. Trautner, T. Vermoesen, I. Vitoriano, M. Wagner, S. Wolff, C. Yue, M. R. Capobianchi, B. Kretschmer, Y. Hall, J. G. Kenny, N. Y. Rickett, G. Dudas, C. E. Coltart, R. Kerber, D. Steer, C. Wright, F. Senyah, S. Keita, P. Drury, B. Diallo, H. de Clerck, M. Van Herp, A. Sprecher, A. Traore, M. Diakite, M. K. Konde, L. Koivogui, N. Magassouba, T. Avsic-Zupanc, A. Nitsche, M. Strasser, G. Ippolito, S. Becker, K. Stoecker, M. Gabriel, H. Raoul, A. Di Caro, R. Wolfel, P. Formenty, and S. Gunther. 2015. Temporal and spatial analysis of the 2014-2015 Ebola virus outbreak in West Africa. Nature 524(7563):97-101.

Chan, M. 2014. Ebola virus disease in West Africa—no early end to the outbreak. N Engl J Med 371(13):1183-1185.

Chertow, D. S., C. Kleine, J. K. Edwards, R. Scaini, R. Giuliani, and A. Sprecher. 2014. Ebola virus disease in West Africa—clinical manifestations and management. N Engl J Med 371(22):2054-2057.

Feldmann, H. 2014. Ebola—a growing threat? N Engl J Med 371(15):1375-1378.

Feldmann, H., S. Jones, H. D. Klenk, and H. J. Schnittler. 2003. Ebola virus: From discovery to vaccine. Nat Rev Immunol 3(8):677-685.

Frieden, T. R., I. Damon, B. P. Bell, T. Kenyon, and S. Nichol. 2014. Ebola 2014—new challenges, new global response and responsibility. N Engl J Med 371(13):1177-1180.

Gates, B. 2015. The next epidemic—lessons from Ebola. N Engl J Med 372(15):1381-1384.

Gire, S. K., A. Goba, K. G. Andersen, R. S. Sealfon, D. J. Park, L. Kanneh, S. Jalloh, M. Momoh, M. Fullah, G. Dudas, S. Wohl, L. M. Moses, N. L. Yozwiak, S. Winnicki, C. B. Matranga, C. M. Malboeuf, J. Qu, A. D. Gladden, S. F. Schaffner, X. Yang, P. P. Jiang, M. Nekoui, A. Colubri, M. R. Coomber, M. Fonnie, A. Moigboi, M. Gbakie, F. K. Kamara, V. Tucker, E. Konuwa, S. Saffa, J. Sellu, A. A. Jalloh, A. Kovoma, J. Koninga, I. Mustapha, K. Kargbo, M. Foday, M. Yillah, F. Kanneh, W. Robert, J. L. Massally, S. B. Chapman, J. Bochicchio, C. Murphy, C. Nusbaum, S. Young, B. W. Birren, D. S. Grant, J. S. Scheiffelin, E. S. Lander, C. Happi, S. M. Gevao, A. Gnirke, A. Rambaut, R. F. Garry, S. H. Khan, and P. C. Sabeti. 2014. Genomic surveillance elucidates Ebola virus origin and transmission during the 2014 outbreak. Science 345(6202):1369-1372.

Gottschalk, R., T. Grünewald, and W. Biederbick. 2009. Aufgaben und Funktion der Ständigen Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Kompetenz-und Behandlungszentren für hochkontagiöse, lebensbedrohliche Erkrankungen. Bundesgesundheitsbl Gesundheitsforsch Gesundheitsschutz 52:214-218.

Heymann, D. L. 2014. Ebola: Learn from the past. Nature 514(7522):299-300.

Judson, S., J. Prescott, and V. Munster. 2015. Understanding Ebola virus transmission. Viruses 7(2):511-521.

Kreuels, B., D. Wichmann, P. Emmerich, J. Schmidt-Chanasit, G. de Heer, S. Kluge, A. Sow, T. Renne, S. Gunther, A. W. Lohse, M. M. Addo, and S. Schmiedel. 2014. A case of severe Ebola virus infection complicated by gram-negative septicemia. N Engl J Med 371(25):2394-2401.

Mackay, I. M., and K. E. Arden. 2015. Ebola virus in the semen of convalescent men. Lancet Infect Dis 15(2):149-150.

Marí Saéz, A., S. Weiss, K. Nowak, V. Lapeyre, F. Zimmermann, A. Dux, H. S. Kuhl, M. Kaba, S. Regnaut, K. Merkel, A. Sachse, U. Thiesen, L. Villanyi, C. Boesch, P. W. Dabrowski, A. Radonic, A. Nitsche, S. A. Leendertz, S. Petterson, S. Becker, V. Krahling, E. Couacy-Hymann, C. Akoua-Koffi, N. Weber, L. Schaade, J. Fahr, M. Borchert, J. F. Gogarten, S. Calvignac-Spencer, and F. H. Leendertz. 2014. Investigating the zoonotic origin of the West African Ebola epidemic. EMBO Mol Med 7(1):17-23.

Reardon, S. 2014. Ebola treatments caught in limbo. Nature 511(7511):520.

RKI (Robert Koch Institute). 2015. Framework Ebola virus disease: Intervention preparedness in Germany. Berlin, Germany: Robert Koch Institute.

Ryan, S. J., and P. D. Walsh. 2011. Consequences of non-intervention for infectious disease in African great apes. PLoS ONE 6(12):e29030.

Schieffelin, J. S., J. G. Shaffer, A. Goba, M. Gbakie, S. K. Gire, A. Colubri, R. S. Sealfon, L. Kanneh, A. Moigboi, M. Momoh, M. Fullah, L. M. Moses, B. L. Brown, K. G. Andersen, S. Winnicki, S. F. Schaffner, D. J. Park, N. L. Yozwiak, P. P. Jiang, D. Kargbo, S. Jalloh, M. Fonnie, V. Sinnah, I. French, A. Kovoma, F. K. Kamara, V. Tucker, E. Konuwa, J. Sellu, I. Mustapha, M. Foday, M. Yillah, F. Kanneh, S. Saffa, J. L. Massally, M. L. Boisen, L. M. Branco, M. A. Vandi, D. S. Grant, C. Happi, S. M. Gevao, T. E. Fletcher, R. A. Fowler, D. G. Bausch, P. C. Sabeti, S. H. Khan, and R. F. Garry. 2014. Clinical illness and outcomes in patients with Ebola in Sierra Leone. N Engl J Med 371(22):2092-2100.

Spencer, C. 2015. Having and fighting Ebola—public health lessons from a clinician turned patient. N Engl J Med 372(12):1089-1091.

Varkey, J. B., J. G. Shantha, I. Crozier, C. S. Kraft, G. M. Lyon, A. K. Mehta, G. Kumar, J. R. Smith, M. H. Kainulainen, S. Whitmer, U. Stroher, T. M. Uyeki, B. S. Ribner, and S. Yeh. 2015. Persistence of Ebola virus in ocular fluid during convalescence. N Engl J Med 372(25):2423-2427.

Vogel, G. 2014. Infectious disease. Are bats spreading Ebola across Sub-Saharan Africa? Science 344(6180):140.

WHO (World Health Organization) Ebola Response Team. 2014. Ebola virus disease in West Africa—the first 9 months of the epidemic and forward projections. N Engl J Med 371(16):1481-1495.

Wolf, T., B. Kreuels, S. Schmiedel, and T. Grünewald. 2014. Ebolaviruserkrankung: Manifestationsformen der infektion. Deutsches Ärzteblatt 111:1522-1523.