1

Introduction and the Process for Revising the WIC Food Packages

The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) was piloted by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food and Nutrition Service (USDA-FNS) in 1972 and enacted into legislation in 1975 (USDA/ERS, 2015). The WIC program is designed to provide specific foods with nutrients determined by nutritional research to be lacking in the diets of the WIC target population (7 C.F.R. § 246). The foods offered by WIC are referred to as the WIC food packages. The food package is comprised of a specific set of foods prescribed to each participant on a monthly basis. This and other terms referenced frequently in the report are defined in Box 1-1.

WIC program services are administered as a federal grant provided to the 50 states and the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, Guam, American Samoa, the American Virgin Islands, the Northern Mariana Islands, and 34 Indian Tribal Organizations (ITOs) (USDA/FNS, 2015a). Services are administered through 90 state agencies which provide the food packages, breastfeeding support, nutrition education, and health and social service referrals to eligible individuals. Eligible individuals fulfill criteria related to age and physiological state, income, and nutritional risk, as summarized in Box 1-2.

In 2015, the WIC program served approximately 8 million women, infants, and children through 1,900 local agencies in 10,000 clinic sites (USDA/FNS, 2015a, 2016). Approximately 54 percent of infants and approximately 31 percent of children ages 1 to less than 5 years in the United States received WIC services in 2014 (USDA/FNS, 2016). WIC also served many mothers of the WIC-participating infants and children. WIC participants can receive benefits through vouchers to purchase the foods

specified in the package. Some states have migrated to an electronic benefit transfer (EBT) card to issue benefits, and all states are required to convert to EBT systems by 2020.

As with other federal nutrition assistance programs,1 WIC is required to provide food and services in alignment with the Dietary Guidelines

__________________

1 Other federal nutrition assistance programs include the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, National School Lunch Program, National School Breakfast Program, Child and Adult Care Food Program, Summer Food Service Program, Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program, and Special Milk Program, among others. WIC participants may also benefit from one or several of these programs. The committee was tasked with evaluation of the WIC food packages exclusively.

for Americans (DGA) (U.S. Congress, P.L. 101-445, 1990;2USDA/HHS, 2016). Given that the DGA are revised every 5 years, review and update of nutrition assistance programs are needed at regular intervals. In 2006, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) proposed revisions to the program for the first time in its 35-year history (IOM, 2006). An evaluation of the food packages is now congressionally mandated to occur every 10 years (P.L. 101-147).3 This report serves as the next required 10-year review (i.e., following the IOM report published in 2006). This introductory chapter provides an overview of the WIC services and food packages, as well as examining the committee’s task and the process for determining what changes to the food packages might be appropriate.

OVERVIEW OF THE WIC PROGRAM

Program Goals

The mission of the WIC program has remained to safeguard the health of low-income women, infants, and children up to age 5 who are at nutritional risk by providing food, nutrition counseling, and access to health services (USDA/ERS, 2015). The program goals, however, have evolved since its introduction. Today they also include promoting and supporting breastfeeding by providing the breastfeeding mother with benefits for up to

__________________

2 101st Congress. 1990. Public law no. 101-445, National Nutrition Monitoring and Related Research Act of 1990.

3 101st Congress. 1989. Public law no. 101-147, Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 1989.

1 year; providing WIC participants with a wider variety of foods, including vegetables, fruits, and whole grains; and providing WIC state agencies greater flexibility in prescribing food packages to accommodate cultural eating patterns4 of WIC participants (USDA/FNS, 2014). WIC supports the national health goals of Healthy People 2020, specifically those related to birth weight, childhood and adult weight, and breastfeeding prevalence (NWA, 2013; HHS, 2015).

The Role of Nutrition Education in WIC

Nutrition education is key in supporting WIC participants’ choices to purchase healthy foods, prepare these foods in a healthful manner, and consume them as part of a diet aligned with the DGA. Indeed, WIC is the only federal supplemental nutrition assistance program to have a nutrition education component required by law (as specified in sections 17(b)(7), 17(f)(1)(C)(x), and 17(j) of the Child Nutrition Act of 1966, as amended, and the Federal WIC regulations in sections 246.2 and 246.11 [USDA/FNS, 2007]). Under these regulations, WIC nutrition education must be “available at no cost to participants; be easily understood by participants; bear a practical relationship to the participant’s nutritional needs, household situation, and cultural preferences; and be designed to achieve the regulatory nutrition education goals” (USDA/FNS/NAL, 2006).

WIC state agencies have the responsibility to develop educational materials that fulfill these federal requirements (USDA/FNS/NAL, 2006). In addition, the food packages themselves provide foods that serve as a tool to meet the dietary goals of the DGA and around which education can be designed.

WIC Breastfeeding Promotion and Support Activities

WIC program activities intended to increase breastfeeding prevalence parallel the three categories of global strategies known to improve breastfeeding outcomes (protection, promotion, and support):

- WIC breastfeeding protection activities include not providing infant formula during the first month after birth to mothers who have expressed their desire to breastfeed.5

__________________

4 This is referenced in the Final Rule as “cultural food preferences.”

5 The Final Rule states: “The issuance of any formula to breastfed infants in the first month after birth is a State agency option. If a State agency chooses this option, it may issue one can of powder infant formula in the container size that provides closest to 104 reconstituted fluid ounces to partially breastfed infants on a case-by case basis. Breastfed infants who are provided this option are considered partially (mostly) breastfed” (USDA/FNS, 2014).

- WIC breastfeeding promotion activities include providing enhanced WIC food packages for breastfeeding mothers compared to fully formula-feeding mothers; counseling on maternal–child health benefits of breastfeeding and of the food packages offered to breastfeeding mothers by WIC; and providing educational materials at WIC clinics.

- WIC breastfeeding support activities include the WIC breastfeeding peer-counseling program, lactation management support offered by certified lactation consultants hired by the program (i.e., certified by the International Lactation Consultant Association), and the provision of breast pumps to women.6

WIC has been actively protecting, promoting, and supporting breastfeeding since 1989, when Congress enacted the first of a series of laws requiring WIC to develop standards to ensure adequate breastfeeding promotion and support at both state and local levels (USDA/FNS, 2013).7 In 1992, Congress required that The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) establish a national breastfeeding promotion program and provided various means by which this could be funded. Two years later, Congress passed the Healthy Meals for Healthy Americans Act, which requires that state WIC agencies spend $21 for each pregnant and breastfeeding woman in support of breastfeeding promotion.

Both WIC and non-WIC breastfeeding promotion and support activities appear to play a critical role in the improvement of breastfeeding initiation, duration, and exclusivity among WIC participants according to the committee’s review of 15 interventional and 3 cross-sectional studies (see Anderson et al., 2005, 2007; Bonuck et al., 2005; Hayes et al., 2008; Meehan et al., 2008; Hopkinson and Konefal Gallagher, 2009; Petrova et al., 2009; Sandy et al., 2009; Bunik et al., 2010; Olson et al., 2010; Pugh et al., 2010; Kandiah, 2011; Whaley et al., 2012; Chapman et al., 2013; Haider et al., 2014; Hildebrand et al., 2014; Howell et al., 2014; Reeder et al., 2014; NASEM, 2016). This is in alignment with global

__________________

6 Although these are common support activities, they are not available universally among WIC state agencies.

7 Based on P.L. 101-147 (1989), states were required to conduct a yearly evaluation of their breastfeeding promotion and support activities, provide nutrition education and breastfeeding materials in languages other than English as appropriate; include in their state plan a plan to provide nutrition education and breastfeeding promotion and a plan to coordinate operations with local agency programs for breastfeeding promotion; and designate a breastfeeding coordinator to provide training on breastfeeding promotion and support to local agency staff responsible for breastfeeding. The annual evaluation of activities is no longer required.

strategies that have proven effective (Pérez-Escamilla and Chapman, 2012; Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2012).8

Additional details about the effects of breastfeeding promotion and support activities among WIC participants are provided in Chapter 2.

The Current WIC Food Packages

The WIC program provides seven types of food packages, as shown in Table 1-1. These packages (numbered I through VII) accommodate different physiological state categories of women, different ages of children, and different developmental stages of infants. In addition, food package III is issued to participants (women, infants, or children) with special medical needs as determined by a physician. The foods offered must meet minimum nutritional specifications, although additional nutritional standards are permitted at the state level. Participants are required to be issued a specific amount of foods in each category (the maximum monthly allowance [MMA]), with the exception of infant formula. Infants that are fully formula-fed may receive an amount of formula between the full nutrition benefit and the MMA. For all infants, the amount of formula should be tailored to meet the needs of the mother-infant dyad.

The revisions proposed by the IOM in 2006 resulted in dramatic changes to the nutrient density of foods in the food packages. For example, an upper limit was set for the amount of total sugars in yogurt, whole grains were required for bread and its substitution options, and the vegetable and fruit cash value voucher (CVV) was added as a new food instrument. These specifications and any modifications proposed by the committee are further reviewed in Chapter 6.

The changes were initially implemented in 2009 (USDA/FNS, 2007) and finalized in 2014 (USDA/FNS, 2014). Tables 1-2 and 1-3 present the composition (in maximum amounts) of the seven different WIC food packages, as defined in the March 2014 Final Rule (USDA/FNS, 2014). Most, but not all, of the IOM’s (2006) recommendations were fully implemented; a few recommendations underwent modification before implementation or were not implemented (see Appendix C, Table C-1). Although most changes were implemented by fall of 2009 in accordance with the Interim Rule (USDA/FNS, 2007), implementation occurred over a period of 6 years (see

__________________

8 Effective global strategies to improve breastfeeding outcomes include protection (e.g., enforcement of the WHO Code for the Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes, labor legislation to support the needs of employed women), promotion (e.g., mass media campaigns, World Breastfeeding Week), and support activities (e.g., the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative, breastfeeding peer counseling programs) (Pérez-Escamilla and Chapman, 2012; Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2012).

TABLE 1-1 Overview of the Current WIC Food Packages and Categorical Eligibility

| Food Package Number | Individuals Eligible by Category* |

|---|---|

| I | Formula-fed, partially breastfed, or fully breastfed infants, ages 0 to less than 6 months |

| II | Formula-fed, partially breastfed, or fully breastfed infants, ages 6 to less than 12 months |

| III | Participants (women, infants, or children) with special medical needs as determined by a physician |

| IV | Children ages 1 to less than 5 years |

| V | Pregnant or partially breastfeeding women (up to 1 year) |

| VI | Postpartum, non-breastfeeding women (up to 6 months) |

| VII | Postpartum, fully breastfeeding women (up to 1 year) |

* Individuals must also meet the income and nutritional risk requirements, as noted in Box 1-2.

SOURCE: USDA/FNS, 2014.

Appendix C, Table C-2). Additional details on the effects of these changes are provided in Chapter 2.

Substitutions Allowed Within the WIC Food Packages

An important change that has been implemented in the current WIC food packages is the ability to substitute foods within many of the food categories. These substitutions allow for more variety and more cultural sensitivity in foods provided by the packages. As noted in the Interim Rule, substitution for a food in the WIC food categories “must be nutritionally equivalent or superior to the food it is intended to replace” (USDA/FNS, 2007). The implication of this statement is that the nutrient content of substitutions for WIC foods should be similar, components (e.g., protein) should be of similar quality, and nutrients should be similarly bioavailable. Although allowed substitutions have been specified by USDA-FNS (2014), WIC state agencies are not required to implement all of them. Table 1-4 provides data on substitutions allowed by WIC state agencies, illustrating the variability in WIC-approved food lists among states.

TABLE 1-2 Full Nutrition Benefit and Maximum Monthly Allowances of Supplemental Foods for Infants in Food Packages I, II, and III

| Foods | Fully Formula Fed (FF) | Partially (Mostly) Breastfed (BF/FF) | Fully Breastfed (BF) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FP I–FF & III–FF A: 0 through 3 months B: 4 through 5 months | FP II–FF & III–FF 6 through 11 months | FP I–BF/FF & III BF/FF A: 0 to 1 montha,b B: 1 through 3 months C: 4 through 5 months | FP II–BF/FF & III BF/FF 6 through 11 months | FP I–BF 0 through 5 months | FP II–BF 6 through 11 months | |

| WIC formulac,d,e,f | A: FNB = 806 fl oz, MMA = 823 fl oz, reconstituted liquid concentrate or 832 fl oz RTF or 870 fl oz reconstituted powder B: FNB = 884 fl oz, MMA = 896 fl oz, reconstituted liquid concentrate or 913 fl oz RTF or 960 fl oz reconstituted powder |

FNB = 624 fl oz, MMA = 630 fl oz, reconstituted liquid concentrate or 643 fl oz RTF or 696 fl oz reconstituted powder | A: 104 fl oz reconstituted powder B: FNB = 364 fl oz, MMA = 388 fl oz, reconstituted liquid concentrate or 384 fl oz RTF or 435 fl oz reconstituted powder C: FNB = 442 fl oz, MMA = 460 fl oz, reconstituted liquid concentrate or 474 fl oz RTF or 522 fl oz reconstituted powder |

FNB = 312 fl oz, MMA = 315 fl oz, reconstituted liquid concentrate or 338 fl oz RTF or 384 fl oz reconstituted powder | — | — |

| Infant cereal | — | 24 oz | — | 24 oz | — | 24 oz |

| Infant food vegetables and fruits | — | 128 oz | — | 128 oz | — | 256 oz |

| Infant food meat | — | — | — | — | — | 77.5 oz |

NOTES: — = the food is not authorized in the corresponding food package; BF = fully breastfed; BF/FF = partially (mostly) breastfed; FF = fully formula fed; FNB = full nutrition benefit; FP = food package; MMA = maximum monthly allowance; RTF = ready-to-feed.

a State agencies have the option to issue not more than one can of powder infant formula in the container size that provides closest to 104 reconstituted fluid ounces to breastfed infants on a case-by-case basis.

b Liquid concentrate and ready-to-feed (RTF) may be substituted at rates that provide comparable nutritive value.

c WIC formula means infant formula, exempt infant formula, or WIC-eligible nutritionals. Infant formula may be issued for infants in food packages I, II and III. Medical documentation is required for issuance of infant formula, exempt infant formula, WIC-eligible nutritionals, and other supplemental foods in food package III. Only infant formula may be issued for infants in food packages I and II.

d The full nutrition benefit is defined as the minimum amount of reconstituted fluid ounces of liquid concentrate infant formula as specified for each infant food package category and feeding variation (e.g., food package IA—fully formula fed).

e The maximum monthly allowance is specified in reconstituted fluid ounces for liquid concentrate, RTF liquid, and powder forms of infant formula and exempt infant formula. Reconstituted fluid ounce is the form prepared for consumption as directed on the container.

f State agencies must provide at least the full nutritional benefit authorized to non-breastfed infants up to the maximum monthly allowance for the physical form of the product specified for each food package category. State agencies must issue whole containers that are all the same size of the same physical form. Infant formula amounts for breastfed infants, even those in the fully-formula fed category should be individually tailored to the amounts that meet their nutritional needs.

SOURCE: Modified from 7 C.F.R. § 246 (USDA/FNS, 2014).

TABLE 1-3 Maximum Monthly Allowances of Supplemental Foods for Children and Women in Food Packages IV, V, VI, and VII

| Foods | Children | Women | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FP IV: 1 through 4 years | FP V: Pregnant and Partially (Mostly) BF (up to 1 year PP)a | FP VI: Postpartum (up to 6 months PP)b | FP VII: Fully Breastfeeding (up to 1 year PP)c,d | |

| Juice, single strengthe | 128 fl oz | 144 fl oz | 96 fl oz | 144 fl oz |

| Milk, fluid | 16 qtf,g,h,i,j | 22 qtf,g,h,i,k | 16 qtf,g,h,i,k | 24 qtf,g,h,i,k |

| Breakfast cereall | 36 oz | 36 oz | 36 oz | 36 oz |

| Cheese | — | — | — | 1 lb |

| Eggs | 1 dozen | 1 dozen | 1 dozen | 2 dozen |

| Fresh vegetables and fruitsm,n | $8.00 in CVV | $11.00 in CVV | $11.00 in CVV | $11.00 in CVV |

| Whole wheat or whole grain breado | 2 lb | 1 lb | — | 1 lb |

| Fish (canned) | — | — | — | 30 oz |

| Legumesp and/or peanut butter | 1 lb or 18 oz | 1 lb and 18 oz | 1 lb or 18 oz | 1 lb and 18 oz |

NOTES: — = the food is not authorized in the corresponding food package; BF = breastfeeding; CVV = cash value voucher; FP = food package; PP = postpartum.

a Food package V is issued to two categories of WIC participants: Women participants with singleton pregnancies; breastfeeding women whose partially (mostly) breastfed infants receive formula from the WIC program in amounts that do not exceed the maximum formula allowances, as appropriate for the age of the infant.

b Food package VI is issued to two categories of WIC participants: Nonbreastfeeding postpartum women and breastfeeding postpartum women whose infants receive more than the maximum infant formula allowances, as appropriate for the age of the infant.

c Food package VII is issued to four categories of WIC participants: Fully breastfeeding women whose infants do not receive formula from the WIC Program; women pregnant with two or more fetuses; women partially (mostly) breastfeeding multiple infants from the same pregnancy; and pregnant women who are also fully or partially (mostly) breastfeeding singleton infants.

d Women fully breastfeeding multiple infants from the same pregnancy are prescribed 1.5 times the maximum allowances.

e Combinations of single-strength and concentrated juices may be issued provided that the total volume does not exceed the maximum monthly allowance for single-strength juice.

f Whole milk is the standard milk for issuance to 1-year-old children (12 through 23 months). At state agency option, fat-reduced milks may be issued to 1-year-old children for whom overweight or obesity is a concern. The need for fat-reduced milks for 1-year-old children must be based on an individual nutritional assessment and consultation with the child’s health care provider if necessary, as established by state agency policy. Low-fat (1%) or nonfat milks are the standard milk for issuance to children ≥24 months of age and women. Reduced fat (2%) milk is authorized only for participants with certain conditions, including but not limited to, underweight and maternal weight loss during pregnancy. The need for reduced fat (2%) milk for children ≥24 months of age (food package IV) and women (food packages V–VII) must be based on an individual nutritional assessment as established by state agency policy.

g Evaporated milk may be substituted at the rate of 16 fl oz of evaporated milk per 32 fl oz of fluid milk or a 1:2 fluid ounce substitution ratio. Dry milk may be substituted at an equal reconstituted rate to fluid milk.

h For children and women, cheese may be substituted for milk at the rate of 1 lb of cheese per 3 qt of milk. For children and women in food packages IV–VI, no more than 1 lb of cheese may be substituted. For fully breastfeeding women in food package VII, no more than 2 lb of cheese may be substituted for milk. State agencies do not have the option to issue additional amounts of cheese beyond these maximums even with medical documentation. (No more than a total of 4 qt of milk may be substituted for a combination of cheese, yogurt or tofu for children and women in food packages IV–VI. No more than a total of 6 qt of milk may be substituted for a combination of cheese, yogurt, or tofu for women in food package VII.)

i For children and women, yogurt may be substituted for fluid milk at the rate of 1 qt of yogurt per 1 quart of milk; a maximum of 1 qt of milk can be substituted. Additional amounts of yogurt are not authorized. Whole yogurt is the standard yogurt for issuance to 1-year-old children (12 through 23 months). At state agency option, low-fat or nonfat yogurt may be issued to 1-year-old children for whom overweight and obesity is a concern. The need for lowfat or nonfat yogurt for 1-year-old children must be based on an individual nutritional assessment and consultation with the child’s health care provider if necessary, as established by state agency policy. Low-fat or nonfat yogurts are the only types of yogurt authorized for children ≥ 24 months of age and women. (No more than a total of 4 qt of milk may be substituted for a combination of cheese, yogurt, or tofu for children and women in food packages IV–VI. No more than a total of 6 qt of milk may be substituted for a combination of cheese, yogurt, or tofu for women in Food Package VII.)

j For children, issuance of tofu and soy-based beverage as substitutes for milk must be based on an individual nutritional assessment and consultation with the participant’s health care provider if necessary, as established by state agency policy. Such determination can be made for situations that include, but are not limited to, milk allergy, lactose intolerance, and vegan diets. Soy-based beverage may be substituted for milk for children on a quart-for-quart basis up to the total maximum allowance of milk. Tofu may be substituted for milk for children at the rate of 1 lb of tofu per 1 quart of milk. (No more than a total of 4 qt of milk may be substituted for a combination of cheese, yogurt, or tofu for children in Food Package IV.) Additional amounts of tofu may be substituted, up to the maximum allowance for fluid milk for lactose intolerance or other reasons, as established by state agency policy.

k For women, soy-based beverage may be substituted for milk on a quart-for-quart basis up to the total maximum allowance of milk. Tofu may be substituted for milk at the rate of 1 lb of tofu per 1 qt of milk. (No more than a total of 4 qt of milk may be substituted for a combination of cheese, yogurt, or tofu for women in food packages V and VI. No more than a total of 6 quarts of milk may be substituted for a combination of cheese, yogurt, or tofu for women in food package VII.). Additional amounts of tofu may be substituted, up to the maximum allowances for fluid milk, for lactose intolerance or other reasons, as established by state agency policy.

l At least one-half of the total number of breakfast cereals on the state agency’s authorized food list must have whole grain as the primary ingredient and meet labeling requirements for making a health claim as a ‘‘whole grain food with moderate fat content’’ as defined in the Final Rule.

m Both fresh fruits and fresh vegetables must be authorized by state agencies. Processed vegetables and fruits, meaning canned (shelf-stable), frozen, and/or dried vegetables and fruits may also be authorized to offer a wider variety and choice for participants. State agencies may choose to authorize one or more of the following processed vegetables and fruits: canned fruit, canned vegetables, frozen fruit, frozen vegetables, dried fruit, and/or dried vegetables. The cash-value voucher may be redeemed for any eligible vegetables and fruits. State agencies may not selectively choose which vegetables and fruits are available to participants. For example, if a state agency chooses to offer dried fruits, it must authorize all WIC-eligible dried fruits.

n The monthly value of the fruit/vegetable cash-value vouchers will be adjusted annually for inflation as described in § 246.16(j).

o Whole wheat and/or whole grain bread must be authorized. State agencies have the option to also authorize brown rice, bulgur, oatmeal, wholegrain barley, whole wheat macaroni products, or soft corn or whole wheat tortillas on an equal weight basis.

p Canned beans may be substituted for dry beans at the rate of 64 oz (e.g., four 16-oz cans) of canned beans for 1 lb dry beans. In food packages V and VII, both beans and peanut butter must be provided. However, when individually tailoring food packages V or VII for nutritional reasons (e.g., food allergy, underweight, participant preference), state agencies have the option to authorize the following substitutions: 1 lb dry and 64 oz canned beans/peas (and no peanut butter); or 2 lb dry or 128 oz canned beans/peas (and no peanut butter); or 36 oz peanut butter (and no beans).

SOURCE: Modified from 7 C.F.R. § 246 (USDA/FNS, 2014), updated with WIC Policy Memorandum #2015-3 and WIC Policy Memorandum #2015-4.

Introduction of the Cash Value Voucher

Implementation of the food packages in 2009 introduced not only new foods, but also the CVV,9 a new type of benefit with a specific dollar value for purchasing vegetables and fruits. States are now required to allow “split tender,” meaning participants may pay the difference out of pocket (or with benefits from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) if their vegetable and fruit purchase exceeds the amount on the CVV (USDA/FNS, 2014).

Overview of the WIC Shopping Process

At the time of this writing, 18 states had implemented the EBT system, and the remainder of states continue to use paper vouchers. With a paper voucher, a participant is required to purchase all WIC foods listed on a voucher in a single shopping trip.10 In contrast, the EBT card allows participants to redeem any portion of the foods issued (for any participating family member) at any time during the month. In either case, the foods must be redeemed in the issued month. In the store, participants must find and choose the state-specific WIC authorized foods. Foods may be identified in a number of ways, for example, by use of a state-prepared food buying guide or by labels posted on the shelf. When using the CVV, participants must calculate the amount of vegetables and fruits that can be covered with $8 or $11 (any overage may be paid out-of-pocket).

When paper vouchers are used, the participant may be required to separate WIC foods from other foods at checkout (see CDPH, 2016). With the EBT system, separation is not typically necessary. For the WIC benefits to be accepted by the vendor, the vendor must have the Universal Product Code (UPC) properly entered into their check-out system.

THE COMMITTEE’S TASK

In response to a request from Congress, USDA-FNS charged the Health and Medicine Division (HMD) of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s11 current Committee to Review the WIC Food Packages to conduct a two-phase evaluation of the WIC food packages and

__________________

9 In states issuing electronic benefit transfer (EBT) cards, the cash value voucher (CVV) is referred to as a cash value benefit (CVB).

10 In some states, specific food categories are issued on a separate check, such as infant formula and the CVV. Other foods are grouped together on one check. Foods like milk are typically issued across multiple vouchers so not all milk has to be purchased at one time.

11 As of March 15, 2016, the Health and Medicine Division continues the consensus studies and convening activities previously undertaken by the Institute of Medicine.

TABLE 1-4 Substitutions Allowed by WIC State Agencies, Fiscal Year 2015

| Authorized Forms | All WIC State Agencies | Percent of WIC Participants Covered by This Optiona | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Agencies | Percent of Agencies | ||

| Milk and milk substitutes | |||

| Soy beverages | 82 | 95 | 99.9 |

| Tofu | 54 | 63 | 72.7 |

| Nonfat, 1%, and 2% milkb | 61 | 71 | 69.1 |

| Nonfat and 1% milkb | 22 | 26 | 28.8 |

| Cheese | |||

| Low sodium | 22 | 26 | 48.3 |

| Fat free | 16 | 19 | 37.1 |

| Low cholesterol | 11 | 13 | 18.3 |

| Peanut butter | |||

| Low sodium | 25 | 29 | 45.3 |

| Low sugar | 17 | 20 | 34.4 |

| Reduced fat | 17 | 20 | 15.6 |

| Beans and peasc | |||

| Canned beans | 73 | 85 | 84.9 |

| Whole grainsd | |||

| Brown rice | 83 | 97 | 99.8 |

| Tortillas | 77 | 90 | 99.6 |

| Oats | 66 | 77 | 85.9 |

| Bulgur and/or barley | 22 | 26 | 22.8 |

| Whole wheat pasta | 25 | 29 | 29.7 |

| Canned fishe | |||

| Any tuna | 86 | 100 | 100 |

| Any salmon | 80 | 93 | 97.7 |

| Sardines | 54 | 63 | 45.7 |

| Any mackerel | 20 | 23 | 6.9 |

| Forms of vegetables and fruits | |||

| Frozen | 70 | 81 | 85.5 |

| Canned | 51 | 59 | 63.4 |

| Dried | 5 | 6 | 16.5 |

NOTES: Data are from the WIC Food Package Policy Options II study (USDA/FNS, 2015b); responses for the study were received from 86 of 90 state agencies, covering 99.98 percent of WIC participants.

a Percentages represent the number of WIC participants linked to the state agencies offering the option.

b The Final Rule established 1% and nonfat milk as standard issuance for women and children ages 2 and older (a change from the Interim Rule, which also included 2 percent milk as standard issuance). The final rule authorizes 2% milk, soy-based beverages, and tofu as substitutions for 1% and nonfat milk based on nutrition assessment and consultation with a healthc are provider if necessary. The Final Rule also permitted yogurt as a milk alternative for women and children. However, since this option was not implemented until after data collection for the study from which this table was derived was completed, data on number of state agencies authorizing yogurt are not documented here.

c The Final Rule permits any type of mature dry beans, peas, or lentils in dry or canned forms. All WIC state agencies authorize some form of dry beans and peas; 81 percent of state agencies authorize all varieties of dry beans and peas.

d WIC state agencies are required to offer whole wheat or whole-grain bread. They also have the option to offer whole-grain alternatives.

e WIC state agencies are required to offer at least two types of canned fish.

SOURCES: USDA/FNS, 2014a, 2015b.

develop recommendations for revising the packages to be consistent with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) (USDA/HHS, 2016). The committee was also charged to consider the health and cultural needs of a diverse WIC-participating population while ensuring the program remains cost-neutral, efficient for nationwide distribution, and straightforward to administer in national, state, and local agencies. The statement of task for this study is presented in Box 1-3. In addition to this, the committee was asked to develop a prioritized set of recommendations for implementation research focusing on data collection, analyses, and other methodological approaches to documenting the impact of the recommended changes to the WIC food packages on anticipated outcomes.

This report is the final of three reports fulfilling the USDA-FNS request. The first report in the series, An Evaluation of White Potatoes in the Cash Value Voucher: Letter Report (IOM, 2015), assessed the impact on food and nutrient intakes of the WIC-participating population of the 2009 regulation to allow the purchase of vegetables and fruits, excluding white potatoes, with a CVV and recommended that white potatoes be allowed as a WIC-eligible vegetable. The second (interim) report, Proposed Framework for Revisions: Interim Report (NASEM, 2016), included a comprehensive review of evidence to support the development of recommendations. This, the final report, includes any relevant updates to the interim report as well as the final recommendations for changes to the WIC food packages. The

remainder of this chapter describes the committee’s task and approach to determining what changes to the food packages might be appropriate.

Special Tasks Requested by the Food and Nutrition Service

In the context of the overall task (see Box 1-3), USDA-FNS requested that the committee evaluate certain foods and food specifications as part of this review. The committee was asked to (1) consider the inclusion of additional fish species in food packages, and consider inclusion of fish across food packages; (2) consider the current science on functional ingredients12

__________________

12 At the time this report was written, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had not established a definition for functional foods or ingredients. Functional ingredients are permitted in foods if evidence indicates the ingredients are safe at estimated national levels of consumption, but efficacy of these ingredients is not evaluated or regulated by the FDA.

added to foods for infants, children, and adults to determine how USDA-FNS might approach the inclusion of foods containing these ingredients in the WIC food packages; and (3) evaluate the evidence related to the current requirement that infant formula be issued based on a reconstituted energy density of 20 kcal/ounce. The related recommendations (as appropriate) are presented in Chapters 6 and 11.

Definition of Supplemental Foods

WIC was designed to be a supplemental food program. The definition of supplemental in this context has evolved since the program’s inception (see Appendix C, “Chronology of Statutes Pertaining to the Definition of

__________________

Broadly, functional foods and ingredients are thought to provide a “health benefit beyond basic nutrition,” and may be beneficial to long-term health (Crowe and Francis, 2013).

WIC Supplemental Foods” for a summary of the definition over time). Most recently, the 2007 Interim Rule defined supplemental foods as

those foods containing nutrients determined by nutritional research to be lacking in the diets of pregnant, breastfeeding, and postpartum women, infants, and children, and foods that promote the health of the population served by the WIC program as indicated by relevant nutrition science, public health concerns, and cultural eating patterns, as prescribed by the Secretary in § 246.10. (P.L. 95-627, § 17)13

The USDA-FNS task to the committee (see Box 1-3) covers all components of this definition (i.e., nutrition, health, breastfeeding practices, and cultural eating patterns of the WIC-participating population), and the recommendations in this report were developed with an awareness of the supplemental nature of the food packages. The committee’s application of this term is further detailed in Chapter 6.

Limitations to the Task

The recommendations in this report were limited by the statement of task, presented in Box 1-3, and are not permitted to go beyond the task. Although the committee acknowledges that WIC participants prepare WIC foods in various ways (e.g., some WIC participants add saturated fats, added sugars, and sodium to foods included in their WIC packages), the committee was not asked to consider how WIC participants modify WIC foods before consumption. In addition, foods considered for the packages were to be readily available or soon to be available in the marketplace by the time the newly revised food packages could be reasonably in place. Finally, changes to USDA-FNS programs that are linked to the WIC food packages but are fiscally independent (e.g., farmers’ markets) were considered for context, but no changes to the functions of such programs are suggested.

THE PROCESS FOR REVISING THE WIC FOOD PACKAGES

In the interim report for this study (NASEM, 2016), the committee outlined an approach to the evaluation and revision of the food packages. The committee’s first step was to design strategies to ensure collection of the required information and to analyze this information as described previously. Next, the committee developed and subsequently modified (see below, “Criteria for Food Package Revisions”) the criteria that it would use to evaluate potential changes to the food packages. The committee also

__________________

13 95th Congress. 1978. P.L. 95-627, § 17: Child care food program.

developed an iterative framework for testing possible changes against the criteria. The three general components of this overall approach (information collection, criteria for revisions, and the iterative framework), plus additional decision tools required to support these activities, are further described in this section.

Approach to Information Collection

The committee developed an approach to the collection of information needed to support the task. The strategies applied are summarized here, with details of the methodologies and findings available in the indicated chapters or appendixes.

Convening Workshops

Over the course of this study, four information-gathering public workshops were held, three in Washington, DC, and one in Irvine, California. Each workshop was followed by a public comment session. The agendas for these workshops are available in Appendix D. Comments provided are available in the public access file for this study.14

Conducting a Comprehensive Literature and Report Review

The committee was tasked with conducting a comprehensive literature review to gather evidence to support its final recommendations.15 In collaboration with HMD staff and committee consultants, draft key research questions were developed based on the statement of task, literature review questions developed for the letter report (IOM, 2015), and other topics outlined by USDA-FNS for committee consideration. The key questions, literature search strategy, and study eligibility criteria were refined using an iterative process. Key findings from the literature review are presented throughout the report where applicable. Details of the literature review methodology are available in Appendix D.

__________________

14 Files may be accessed by emailing paro@nas.edu.

15 Time and resources were inadequate to carry out a full systematic review. Specifically, the last two steps of a systematic review process were not completed: (1) risk of bias evaluation, and (2) evidence synthesis (which includes evaluation of the strength of the evidence).

Analyzing Food and Nutrient Intakes and Diet Quality of WIC and WIC-Eligible Populations16

HMD was tasked with carrying out two comparisons: (1) nutrient intake of WIC participants compared to WIC-eligible nonparticipants, and (2) nutrient intake of WIC participants before the 2009 food package changes compared to after the 2009 food package changes. For this task, the committee analyzed data from survey years 2005 to 2012 of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Details of the analysis and results are available in Chapter 4 and Appendix J.

Determining WIC Food Package Food, Nutrient, and Cost Profiles

The food group and nutrient contributions and costs of the current food packages served as the baseline from which to evaluate food package changes. Details of the food group and nutrient contributions of the current food packages, along with a comparison to dietary intake recommendations, are presented in Chapter 3. Details of the food group and nutrient contributions of the revised food packages are included in Chapter 9 and Appendix T. A cost analysis is presented in Chapter 7. Appendix R details the assumptions applied to develop the nutrient and cost profiles.

Conducting Sensitivity and Regulatory Impact Analyses

A sensitivity analysis was applied to the revised food package profiles to assess the effects of alternative potential food package changes on (1) the nutrient and food group composition of the packages relative to the DGA recommended food groups and subgroups, and (2) cost. This analysis considered different potential changes to food amounts, redemption, and/or participation to develop the cost-neutral revised food packages. In addition to the sensitivity analysis, a regulatory impact analysis (RIA) was conducted to evaluate the effect of the committee’s recommended changes in WIC food packages on program participation, the value of selected food packages, and program cost and administration. Details of the sensitivity and RIA approaches and results are presented in Chapters 8 and 10, respectively.

Conducting a Food Expenditure Analysis

The committee was required to conduct an evaluation of the food costs of WIC-participating households, including individual expenditures on

__________________

16 In accordance with the task, data were also generated for low-income women that were ineligible because they were not pregnant, breastfeeding, or postpartum.

separate food groups, to assess the relative contribution of the WIC food packages to household total food expenditures. The methods for and results of this analysis are presented in Chapter 2. Additional details are provided in the phase I report (NASEM, 2016).

Visiting WIC Sites and Shopping for WIC Foods

USDA-FNS asked that the majority of committee members visit a WIC site and experience shopping as a WIC participant prior to development of the phase I (interim) report. Between March and June 2015, committee members visited a total of 14 WIC sites and vendors either in their home state, another state, or both. The visits were organized to ensure geographic and cultural diversity, a balance of sites issuing paper vouchers versus using EBT, and activity at the site (e.g., participant flow and provision of nutrition education). A list of sites visited by city and state, as well as a summary of the committee’s impressions from this experience, is presented in Appendix D.

Reviewing Public Comments

As required by USDA-FNS, comments were solicited through the HMD study website and in-person at five public comment sessions over the course of the study. A summary of common themes is presented in Appendix D.

Criteria for Food Package Revisions

Criteria for food package revisions were presented in the committee’s phase I report (NASEM, 2016). To develop the criteria, the committee examined the criteria outlined by the 2006 IOM committee. The committee used these criteria for this review, with only slightly modified language. This was because, after a thorough review of the evidence, the committee concluded that the 2006 criteria were comprehensive and remained appropriate to include. After phase I, an additional criterion (criterion 1) was added because the committee determined that it was required to guide its work and permit it to meet its task. The final criteria, presented in Box 1-4, reflect the committee’s priorities, first, to meet the goals of the WIC program; second, to respond to the requirement that the WIC food packages be aligned with the DGA; and third, to provide a package that is acceptable to participants and feasible to implement at every level. In this section, the rationale supporting each criterion is described. The degree to which the revised food packages meet these criteria is evaluated in Chapter 9.

Criterion 1: Providing a Supplement to the Diet

The packages provide a balanced supplement to the diets of women and children.

Rationale The concept of the WIC program providing a supplemental amount of food to participants is part of the full name of the WIC program, namely the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. The current food packages provide widely varying proportions of required nutrients and recommended food groups (see Chapter 3) and a better balance in these proportions would permit the committee to align the food packages more adequately with the DGA. The committee decided that, because WIC participants (other than formula-fed infants in the first 6 months of life), consume foods and beverages not supplied by the WIC food packages that meet some portion of their nutrient needs, the supplementation target (i.e., proportion of requirement) should be to meet a moderate proportion of an individual’s requirement for a particular nutrient or recommended amount of a food group. Furthermore, the committee decided that the supplementation target may differ depending on the nutrient requirement and the degree to which foods appropriate for the food package and available in the marketplace could meet this requirement.

Criterion 2: Optimizing Nutrient Intakes

The packages contribute to reduction of the prevalence of inadequate nutrient intakes and of excessive nutrient intakes.

Rationale WIC is a supplemental food program designed to provide specific nutrients determined by nutritional research to be lacking in the diets of the WIC-participating population. As described in Chapter 4, the committee’s evaluation of nutrient intakes among WIC-eligible populations led to the identification not only of nutrients for which intakes were inadequate, but also nutrients for which intakes were excessive. Restrictions on food types, as well as on added salt, sugars, and saturated fats, are all intended to reduce excessive intake of these nutrients. Nutrition education through WIC that is linked to the food packages also helps to ensure that participants’ overall diets align with their energy and nutrient needs as well as with the DGA. However, inasmuch as WIC is a “supplemental nutrition program,” it cannot be expected to alleviate all nutritional deficits or excesses in participants’ diets. Nutrient intake is evaluated in Chapter 4, and nutrients are prioritized based on the prevalence of inadequate or excessive intakes in Chapter 5. The committee’s interpretation of the term supplemental is described above and discussed further in Chapter 6.

Criterion 3: Aligning with the Most Recent Dietary Guidelines for Americans

The packages contribute to an overall dietary pattern that is consistent with the DGA for individuals 2 years of age and older.

Rationale A goal of the final recommendations is to ensure that WIC food packages are consistent with the DGA. The food package composition was compared to the DGA food patterns appropriate for the age and physiological state of package recipients. Food packages were also evaluated for provision of nutrients of public health concern and nutrients to limit (added sugars, saturated fat, and sodium).

Criterion 4: Aligning with the Most Recent Dietary Guidance for Individuals Younger Than 2 Years of Age

The packages contribute to an overall diet that is consistent with established dietary recommendations for infants and children less than 2 years of age, including encouragement of and support for breastfeeding.

Rationale Because the DGA do not apply to infants and children less than 2 years of age, WIC food packages should be consistent with guidance from other authorities for subgroups within this age range, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, and the World Health Organization. Promotion of breastfeeding is an overarching goal of the WIC program, however, the proportion of WIC women who breastfeed falls below the proportion of overall low-income women and well below the Healthy People 2020 objectives (Ryan et al., 2002; CDC, 2015; HHS, 2015). Therefore, attention was paid to how the revised food packages can motivate breastfeeding. Chapter 3 contains additional detail on the dietary guidance identified by the committee and its application to infants and children less than 2 years of age.

Criterion 5: Suitability and Safety for Individuals with Limited Transportation, Storage Options, and Cooking Facilities

The foods in the packages are available in forms and amounts suitable for low-income persons who may have limited transportation options, storage, and cooking facilities.

Rationale Access to WIC vendors is limited in many areas where WIC participants live, as are cooking and food-storage facilities in their homes. As a result, the WIC food packages must be designed to consider these barriers to acquisition, transportation, and safe consumption of WIC foods.

Criterion 6: Acceptability, Availability, and Perceived Value

The foods in the packages are readily acceptable, commonly consumed, widely available, take into account cultural eating patterns and food preferences, and provide incentives for families to participate in the WIC program.

Rationale Consumption of WIC foods may be influenced by the acceptability, preferences for, or availability of foods that are issued in the food packages. Definitions of acceptability, availability, and related terms are provided below; acceptability, accessibility, and cultural considerations are reviewed in Chapters 2 and 3.

Acceptability Food acceptability means that foods provided are easily incorporated into the diet, considering many different factors. Employment is one factor that may affect dietary patterns and the extent to which acquired or purchased WIC foods are actually consumed. Time constraints and a need for convenience are important when considering possible

modifications to the WIC food packages. Additionally, some individuals have food-triggered, immune-mediated sensitivities that require specific foods or diets. These include food allergies, celiac disease, non-celiac gluten sensitivity, and lactose intolerance. The committee considered how the current food packages could be improved to meet the needs of the diverse WIC-participating population.

Commonly consumed USDA’s strategy for generating the DGA recommended food intake patterns starts with understanding the actual eating patterns of Americans to ensure that recommendations are compatible with these patterns. Similarly, it was important for the committee to consider the current food packages and possible changes in the context of what WIC participants actually eat. Redemption data and national food intake data were key sources of this information.

Food availability and accessibility Measures of food accessibility include the distance of WIC participants to WIC vendors, how participants access stores (by car or other transportation), and where (at large or small stores) participants primarily shop for foods. Using one’s own vehicle allows more flexibility in store choice; lack of a vehicle limits the ability to transport large or heavy items or a large number of items. The committee also considered the availability of food types and sizes in the marketplace.

Cultural considerations Culture can be defined as shared beliefs, values, and behaviors of groups of people that influence their specific needs and preferences (NWA, 2003). The committee interpreted culturally suitable foods as foods that align with food preferences and feeding practices based on a participant’s ethnic identity and religion. Such foods could complement cultural eating practices or behaviors while still providing nutrients for which intake is found to be lacking. Several changes to the food packages in 2009 were made to allow flexibility with consideration to cultural needs (IOM, 2006). The current committee also considered how WIC food packages accommodate preferences for vegetarian and vegan diets, food-related religious practices (e.g., Kosher and Halal diets), and other preferences.

Perceived value Participation in WIC and redemption and consumption of WIC foods may be somewhat dependent upon the perceived value of the food packages (as an incentive) and other services provided. Food packages that draw participation can encourage continued enrollment and use of the nutrition education, breastfeeding support, and health services accessible through WIC. The converse may also be true, meaning that providing these services and support may help WIC participants attach more value to their WIC foods. The committee examined additional possibilities

for promoting the choice to breastfeed, which are reflected in the revised food packages presented in Chapter 6.

Criterion 7: Moderating Administrative Burden

The foods in the packages do not create an undue burden on state agencies or vendors.

Rationale The WIC program is administered by USDA-FNS and numerous state and local agencies. As specified in the task, the proposed changes should not unduly add to the administrative burden of these agencies.17 Likewise, changes should not unduly add to WIC vendor burden, given that the ease of WIC program administration is closely linked to the ability of WIC-authorized vendors to provide WIC foods. Additional detail on the committee’s evaluation of the effect of the 2009 food packages changes on state agency and vendor burden is presented in Chapter 2.

Framework for Revisions

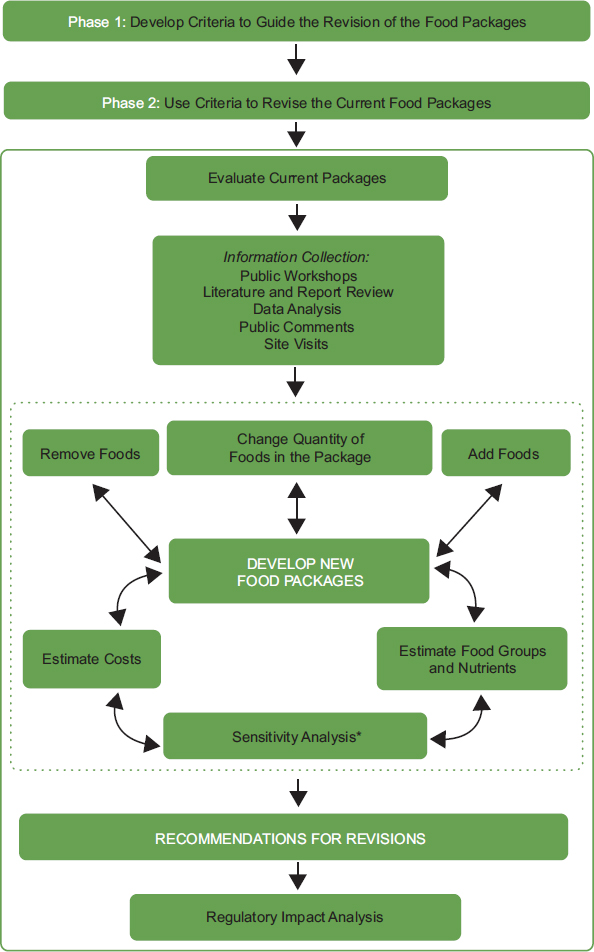

The committee’s overall process for revising the WIC food packages is illustrated in Figure 1-1. The objective was to ensure that the revisions fell within the criteria outlined in the previous section. First, the current food packages were evaluated for the nutrients and food groups provided as well as the challenges faced during implementation. After reviewing this information, the committee identified priority changes in the food packages and tested possible changes in an iterative fashion to align with the criteria. The sensitivity analysis was used to determine the extent to which particular changes affected nutrients, food groups, and costs. As a final step, the revised packages were further changed to ensure cost-neutrality, considering the committee’s priority changes. This process involved nutritional and cost trade-offs, with final recommendations guided by the criteria and cost constraints. Once the iterations resulted in changes meeting the criteria, recommendations were finalized. A regulatory impact analysis was then conducted to assess the projected effect of changes in WIC food packages on program participation, the value of the food packages as selected, and program costs and administration.

__________________

17 Administrative burden includes adding unreasonably to staff time and effort, requiring additional systems that are not already in place, or requiring any program modifications that would be disproportionate to the benefit of the change.

NOTES: The dotted line indicates components of the process that iterate until the criteria for food package revisions are met (see criteria 1 through 7 presented above). * The sensitivity analysis tests the assumptions applied to develop the cost-neutral revised food packages. For example, if redemption of a food in the final revised package was assumed to be 80 percent, the sensitivity analysis could test effects on cost, nutrients, and food groups should redemption rise to 90 percent. A description of the sensitivity analysis is provided in Chapter 8.

Qualitative Assessment of Food Package Changes

The committee considered additional dimensions that could be affected by changes to the food packages. These included the effects of changes on participation (uptake) in the program and/or effects on the redemption rates of foods within each package, over the 5 years following implementation. These changes were particularly relevant for conducting the RIA, and several major changes were included as an option in the RIA (see Chapter 10 and Appendix U for details on the execution and results of the RIA). Examples include an increase in the rates of CVV redemption or shifts of participants from fully formula feeding to partially breastfeeding.

Variations from Cost-Neutral

Although the committee was tasked with ensuring overall cost-neutrality for recommended changes to the WIC food packages, it was also asked to offer prioritized recommendations in the event that USDA-FNS’s WIC funding is either above or below the cost-neutral level. These priorities appear in Chapter 11.

Determining Foods to Be Added, Deleted, or Changed in the Food Packages

The committee’s consideration of possible changes to the food packages was based on the concept of the food packages as supplemental. (See Chapter 6 for a discussion of the committee’s interpretation of “supplemental.”) As such, the food packages should supplement participants’ diets with foods containing nutrients that are both underconsumed and linked to health outcomes relevant to the WIC-participating population. The committee considered whether to add foods or to allow for additional or more costly food options that could address these inadequacies as well as alignment with the DGA. To make these changes possible, the committee identified foods currently in the food packages that could be reduced or removed. To do this, the committee evaluated the packages for foods that (1) were provided in more than a supplemental amount in comparison to the DGA; (2) were not associated with nutrient inadequacies and food groups for which intake was below recommended amounts or were of lower priority related to these inadequacies; (3) contributed to either excess energy intake or excess intake of saturated fat, added sugars, sodium, and refined grains, and (4) were poorly redeemed or were not redeemed because of food preference, availability, or other reasons. These concepts were considered in balance with cost. The committee also sought opportunities to improve the value of the breastfeeding packages.

Aligning Guidance for Nutrients and Foods

The committee faced a fundamental challenge when evaluating dietary adequacy for nutrients, which are based on nutrient requirements described in the Dietary Reference Intakes (DRI), compared to food groups, which are based on recommendations in the DGA. This challenge stems from differences in the methods used to establish dietary adequacy and differences in how the two sets of guidelines are used to plan diets for groups of individuals.

To evaluate dietary adequacy for nutrients based on the DRI, the Estimated Average Requirement (EAR) is used. The EAR is the daily intake estimated to meet the nutrient requirement of half the healthy individuals in a particular life stage, sex, and age group. Thus, it is the median of the distribution of requirements in that group. In planning diets for groups, the objective is to minimize the proportion of individuals with usual daily intakes below the EAR (IOM, 2003). In the committee’s deliberations, nutrients were considered underconsumed if the prevalence of inadequacy was 5 percent or greater, meaning that at least 5 percent of individuals in the subgroup consumed less than the EAR. Using this approach, the committee identified 15 nutrients as being consumed in inadequate amounts in at least one subgroup of WIC women. A proportion of the reported dietary inadequacies could have resulted from underreporting of energy intake, which is a common problem in dietary surveys, including NHANES (Briefel et al., 1997; Macdiarmid and Blundell, 1998; McKenzie et al., 2002; CDC, 2010; Archer et al., 2013; Murakami and Livingstone, 2015; Subar et al., 2015). As a result of this problem, the committee gave priority to those nutrients for which the prevalence of inadequacy was greater than 50 percent, followed by those for which the prevalence was between 10 and 50 percent and, finally, by those for which the prevalence was between 5 and 10 percent (see Chapter 5).

In contrast to nutrients, food group intakes are assessed using the DGA food patterns, which are designed to ensure that the nutrient requirements of nearly all (97.5 percent) individuals in a particular life stage, sex, and age group are met. The DGA food patterns are based on providing the Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) for all (or most) nutrients; the RDA for each nutrient is the DRI value for that nutrient that is two standard deviations above its EAR. Inasmuch as the food patterns are designed to meet all (or most) of the RDAs, recommended intakes for some of the more easily obtained nutrients can be well above their RDAs (Britten et al., 2012). For example, because protein-containing foods are also good sources of iron and zinc, food patterns designed to meet the RDAs for iron and zinc (less easily obtained nutrients) can result in a recommended intake of protein (a more easily obtained nutrient) being well above its RDA. Inasmuch as the

DGA recommendation may be higher than even the RDA, the prevalence of intakes that are below recommended food patterns may be higher than the prevalence of intakes that are below the nutrient EARs. This discrepancy was evident among children 2 to less than 5 years old, among whom inadequate nutrient intakes were rare, but food-group intakes below the food pattern recommendations were common.

As a result of these considerations, the committee first used the prevalence of nutrient inadequacy, in conjunction with evidence of a health consequence relevant to the WIC-participating population, to identify the priority nutrients among groups of WIC participants. Alignment of the food packages with the DGA food groups took place at a later step and involved a similarly structured process. The committee chose a less-restrictive approach for selecting the foods group intakes that should be improved than the one (described above) that was used for selecting which nutrient intakes should be improved. For food groups, if 50 percent or more of the population group fell below the recommended intake, then the committee thought that improving intake of this food group should be a priority; if 75 percent or more of the population group fell below the recommended intake, then the committee thought that improving intake of this food group should be a higher priority.

SUMMARY AND ORGANIZATION OF THIS REPORT

In summary, the committee applied the iterative process of the framework (see Figure 1-1) to ensure that the revised food packages met the seven overarching criteria (see Box 1-4). The remainder of this report provides details on the methodologies applied, as well as the findings, conclusions and recommendations resulting from the process. The chapter contents are as detailed below:

Chapter 2—Changes Since the Last Review and Continuing Challenges

Chapter 3—Alignment of the Current Food Packages with Dietary Guidance, Special Dietary Needs, and Cultural Eating Practices or Food Preferences

Chapter 4—Nutrient and Food Group Intakes of WIC Participants

Chapter 5—Nutrient and Food Group Priorities for the Food Packages

Chapter 6—The Revised Food Packages

Chapter 7—Evaluation of Cost

Chapter 8—Sensitivity Analysis

Chapter 9—How the Revised Food Packages Meet the Criteria Specified

Chapter 10—The Regulatory Impact Analysis (Abridged)

Chapter 11—Recommendations for Implementation and Research

Overall, this report presents findings and other information intended to guide the USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service to improve the supplemental food portion of the WIC program, improve the nutritional status of WIC participants, promote breastfeeding, and, indirectly, facilitate making the nutrition education component of the WIC program more consistent with the DGA (USDA/HHS, 2016).

REFERENCES

Anderson, A. K., G. Damio, S. Young, D. J. Chapman, and R. Peréz-Escamilla. 2005. A randomized trial assessing the efficacy of peer counseling on exclusive breastfeeding in a predominantly Latina low-income community. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 159(9):836–841.

Anderson, A. K., G. Damio, D. J. Chapman, and R. Peréz-Escamilla. 2007. Differential response to an exclusive breastfeeding peer counseling intervention: The role of ethnicity. Journal of Human Lactation 23(1):16–23.

Archer, E., G. A. Hand, and S. N. Blair. 2013. Validity of U.S. nutritional surveillance: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey caloric energy intake data, 1971–2010. PLoS One 8(10):e76632.

Bonuck, K. A., K. Freeman, and M. Trombley. 2005. Country of origin and race/ethnicity: Impact on breastfeeding intentions. Journal of Human Lactation 21(3):320–326.

Briefel, R. R., C. T. Sempos, M. A. McDowell, S. Chien, and K. Alaimo. 1997. Dietary methods research in NHANES III: Under-reporting of energy intake. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 65(S):1203S–1209S.

Britten, P., L. E. Cleveland, K. L. Koegel, K. J. Kuczynski, and S. M. Nickols-Richardson. 2012. Updated US Department of Agriculture food patterns meet goals of the 2010 dietary guidelines. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 112(10): 1648–1655.

Bunik, M., P. Shobe, M. E. O’Connor, B. Beaty, S. Langendoerfer, L. Crane, and A. Kempe. 2010. Are 2 weeks of daily breastfeeding support insufficient to overcome the influences of formula? Academic Pediatrics 10(1):21–28.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2010. Obesity and socioeconomic status in adults: United States, 2005–2008. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db50.pdf (accessed December 20, 2016).

CDC. 2015. Bridged-race population estimates 1990–2014 request. http://wonder.cdc.gov/bridged-race-v2014.html (accessed August 29, 2016).

CDPH (California Department of Public Health). 2016. WIC authorized food list shopping guide. http://www.cdph.ca.gov/programs/wicworks/WIC%20Foods/WICAuthorizedFoodListShoppingGuide-3-28-2016.pdf (accessed October 27, 2016).

Chapman, D. J., K. Morel, A. Bermudez-Millan, S. Young, G. Damio, and R. Peréz-Escamilla. 2013. Breastfeeding education and support trial for overweight and obese women: A randomized trial. Pediatrics 131(1):e162–e170.

Crowe, K. M., and C. Francis. 2013. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Functional foods. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition Dietetics 113(8):1096–1103.

Haider, S. J., L. V. Chang, T. A. Bolton, J. G. Gold, and B. H. Olson. 2014. An evaluation of the effects of a breastfeeding support program on health outcomes. Health Services Research 49(6):2017–2034.

Hayes, D. K., C. B. Prince, V. Espinueva, L. J. Fuddy, R. Li, and L. M. Grummer-Strawn. 2008. Comparison of manual and electric breast pumps among WIC women returning to work or school in Hawaii. Breastfeeding Medicine 3(1):3–10.

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2015. Healthy People 2020: Maternal, infant, and child health objectives. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/maternal-infant-and-child-health/objectives (accessed December 20, 2016).

Hildebrand, D. A., P. McCarthy, D. Tipton, C. Merriman, M. Schrank, and M. Newport. 2014. Innovative use of influential prenatal counseling may improve breastfeeding initiation rates among WIC participants. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 46(6):458–466.

Hopkinson, J., and M. Konefal Gallagher. 2009. Assignment to a hospital-based breastfeeding clinic and exclusive breastfeeding among immigrant Hispanic mothers: A randomized, controlled trial. Journal of Human Lactation 25(3):287–296.

Howell, E. A., S. Bodnar-Deren, A. Balbierz, M. Parides, and N. Bickell. 2014. An intervention to extend breastfeeding among black and Latina mothers after delivery. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 210(3):239.e231–e235.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2003. Dietary Reference Intakes: Applications in dietary planning. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2006. WIC food packages: Time for a change. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2015. Review of WIC food packages: An evaluation of white potatoes in the cash value voucher: Letter report. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Kandiah, J. 2011. Teaching new mothers about infant feeding cues may increase breastfeeding duration. Food and Nutrition Sciences 2(4):259–264.

Macdiarmid, J., and J. Blundell. 1998. Assessing dietary intake: Who, what and why of underreporting. Nutrition Research Reviews 11(2):231–253.

McKenzie, D. C., R. K. Johnson, J. Harvey-Berino, and B. C. Gold. 2002. Impact of interviewer’s body mass index on underreporting energy intake in overweight and obese women. Obesity Research and Clinical Practice 10(6):471–477.

Meehan, K., G. G. Harrison, A. A. Afifi, N. Nickel, E. Jenks, and A. Ramirez. 2008. The association between an electric pump loan program and the timing of requests for formula by working mothers in WIC. Journal of Human Lactation 24(2):150–158.

Murakami, K. and M. B. Livingstone. 2015. Prevalence and characteristics of misreporting of energy intake in US adults: NHANES 2003–2012. British Journal of Nutrition 114(8):1294–1303.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2016. Review of WIC food packages: Proposed framework for revisions: Interim report. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/21832.

NWA (National WIC Association). 2003.WIC culturally sensitive food prescription recommendations. Washington, DC: National WIC Association. https://s3.amazonaws.com/aws.upl/nwica.org/WIC_Culturally_Sensitive_Food_Prescription.pdf (accessed August 24, 2016).

NWA. 2013. The role of WIC in public health. Washington, DC: National WIC Association. https://s3.amazonaws.com/aws.upl/nwica.org/WIC_Public_Health_Role.pdf (accessed December 20, 2016).

Olson, B. H., S. J. Haider, L. Vangjel, T. A. Bolton, and J. G. Gold. 2010. A quasi-experimental evaluation of a breastfeeding support program for low income women in Michigan. Maternal and Child Health Journal 14(1):86–93.

Pérez-Escamilla, R., and D. J. Chapman. 2012. Breastfeeding protection, promotion, and support in the United States: A time to nudge, a time to measure. Journal of Human Lactation 28(2):118–121.

Pérez-Escamilla, R., L. Curry, D. Minhas, L. Taylor, and E. Bradley. 2012. Scaling up of breastfeeding promotion programs in low- and middle-income countries: The “breastfeeding gear” model. Advances in Nutrition 3(6):790–800.

Petrova, A., C. Ayers, S. Stechna, J. A. Gerling, and R. Mehta. 2009. Effectiveness of exclusive breastfeeding promotion in low-income mothers: A randomized controlled study. Breastfeeding Medicine 4(2):63–69.

Pugh, L. C., J. R. Serwint, K. D. Frick, J. P. Nanda, P. W. Sharps, D. L. Spatz, and R. A. Milligan. 2010. A randomized controlled community-based trial to improve breastfeeding rates among urban low-income mothers. Academic Pediatrics 10(1):14–20.

Reeder, J. A., T. Joyce, K. Sibley, D. Arnold, and O. Altindag. 2014. Telephone peer counseling of breastfeeding among WIC participants: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics 134(3):e700–e709.

Ryan, A., Z. Wenjun, and A. Acosta. 2002. Breastfeeding continues to increase into the new millennium. Pediatrics 11(6):1103–1109.

Sandy, J. M., E. Anisfeld, and E. Ramirez. 2009. Effects of a prenatal intervention on breastfeeding initiation rates in a Latina immigrant sample. Journal of Human Lactation 25(4):404–411; quiz 458–459.

Subar, A. F., L. S. Freedman, J. A. Tooze, S. I. Kirkpatrick, C. Boushey, M. L. Neuhouser, F. E. Thompson, N. Potischman, P. M. Guenther, V. Tarasuk, J. Reedy, and S. M. Krebs-Smith. 2015. Addressing current criticism regarding the value of self-report dietary data. Journal of Nutrition 145(12):2639–2645.

USDA/ERS (U.S. Department of Agriculture/Economic Research Service). 2015. The WIC program: Background, trends, and economic issues, 2015 edition. Washington, DC: USDA/ERS. http://www.ers.usda.gov/media/159295/err73.pdf (accessed December 20, 2016).

USDA/FNS (U.S. Department of Agriculture/Food and Nutrition Service). 2007. Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC): Revisions in the WIC food packages; Interim Rule. 7 C.F.R. § 246.

USDA/FNS. 2013. WIC participant and program characteristics 2012 final report. Alexandria, VA: USDA/FNS. http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/WICPC2012.pdf (accessed December 20, 2016).

USDA/FNS. 2014. Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC): Revisions in the WIC food packages; final rule. 7 C.F.R. § 246.

USDA/FNS. 2015a. About WIC—WIC at a glance. http://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/about-wic-wic-glance (accessed December 20, 2016).

USDA/FNS. 2015b. WIC food packages policy options II, final report. Alexandria, VA: USDA/FNS. http://www.fns.usda.gov/wic-food-package-policy-options-ii (accessed November 11, 2015).

USDA/FNS. 2016. Frequently asked questions about WIC. http://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/frequently-asked-questions-about-wic (accessed May 22, 2016).

USDA/FNS/NAL (U.S. Department of Agriculture/Food and Nutrition Service/National Agricultural Library). 2006. WIC program nutrition education guidance. http://www.nal.usda.gov/wicworks/Learning_Center/ntredguidance.pdf (accessed September 4, 2015).

USDA/HHS (U.S. Department of Agriculture/U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2016. 2015–2016 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015 (accessed August 29, 2016).

Whaley, S. E., M. Koleilat, M. Whaley, J. Gomez, K. Meehan, and K. Saluja. 2012. Impact of policy changes on infant feeding decisions among low-income women participating in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. American Journal of Public Health 102(12):2269–2273.