2

Characterizing the Users and Providers of Long-Term Services and Supports

To provide a framework for the workshop’s discussions, two keynote speakers discussed the characteristics and needs of those adults who use long-term services and supports and the makeup of the workforce that provides those services and supports. H. Stephen Kaye, professor at the Institute for Health & Aging and the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences at the University of California, San Francisco, gave a keynote presentation on the characteristics and needs of long-term services and supports users. Luis Padilla, associate administrator for health workforce at the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), then discussed his agency’s efforts to develop the necessary workforce to meet those needs.

CHARACTERISTICS AND NEEDS OF LONG-TERM SERVICES AND SUPPORTS USERS

H. Stephen Kaye

Professor, University of California, San Francisco

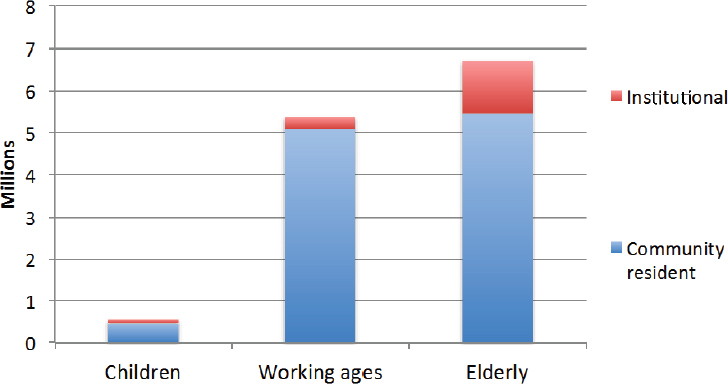

The vast majority of the 12 million Americans who need long-term services and supports live in the community, said H. Stephen Kaye of the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). Approximately 1.5 million of the individuals needing long-term services and supports live in institutions—most of them are elderly and living in nursing homes (see Figure 2-1). However, contrary to popular belief, only half of those who

SOURCE: Kaye, 2016. Reprinted with permission from H. Stephen Kaye.

need long-term services and supports and live in the community are elderly, which means that the issue of long-term services and supports is not solely relevant to older adults. Kaye focused the remainder of his presentation on individuals living in the community.

Among children who need long-term services and supports, the primary reasons they need such services are the presence of developmental, intellectual, or other cognitive disabilities; mental health-related disabilities and various types of physical disabilities account for a smaller proportion of the reasons children need services and supports. The relative distribution changes as people age, said Kaye, such that in the working-age population, back and spine problems are the leading causes of needing long-term services and supports, followed by intellectual disability, arthritis, mental health issues, and heart conditions. As people reach much older ages, physical disabilities become more prevalent than cognitive disabilities, and arthritis becomes the leading reason for needing long-term services and supports, followed by back and spine problems, heart conditions, dementia, and diabetes.

The age of disability onset also varies across the age spectrum. Most children who need long-term services and supports have their disability at birth or acquire it soon thereafter. In contrast, approximately two-thirds of working-age adults and 92 percent of older adults acquired their disability in adulthood. Many older adults needing long-term services and

supports acquired their disability after they stopped working, meaning that those individuals would have had the same opportunity to earn money and accumulate wealth as others in their age cohort who did not acquire a disability. This, Kaye said, is one of the reasons that poverty is less prevalent, albeit still high, among older adult users of long-term services and supports than it is among younger users. Specifically, more than 50 percent of older adult users of long-term services and supports and 60 percent of working-age adults and children who use long-term services and supports have household incomes that are below twice the poverty level.

Kaye’s analysis of 2010 data from the Census Bureau’s Survey of Income and Program Participation1 found that approximately half of users of long-term services and supports (6.6 million people) need minimal support, typically help with getting out into the community, help with housework, or both (see Table 2-1). Nearly all of the individuals in this group get help from unpaid sources such as family and friends. Another approximately 25 percent of individuals who receive services and supports (3.0 million people) also need help preparing meals, and may need help managing medications and money. Again, Kaye said, most of these individuals get help from unpaid sources, with only 14 percent getting paid help. Individuals in the community who also need help with activities of daily living2 total about 1.4 million people, and 20 percent of these individuals receive those services from paid help. An additional 1.1 million people also need help eating and toileting; approximately 22 percent of these individuals have paid help. “In general,” Kaye said, “paid help is for most people, I think, not a default but something they do if they don’t have unpaid sources of help readily available.”

Many needs, however, remain unmet, Kaye said. Some 20 to 30 percent of users of long-term services and supports in the general population report that they have unmet needs, and one survey of Massachusetts residents who had disabilities found the rate of unmet need to be as high as 70 percent (Mitra et al., 2011). Even among those individuals who participate in home and community-based services programs such as Medicaid, the percentages with unmet needs ranges from 34 to 58 percent (Brown et al., 2007). Furthermore, research conducted by Kaye and his colleagues found that 39 percent of the participants in California’s in-home supportive services system, Cal MediConnect, said their needs were not

___________________

1 For more information, see http://www.census.gov/sipp (accessed September 23, 2016).

2 Activities of daily living are routine, everyday tasks, such as bathing, dressing, eating, toileting, transferring from bed to chair, and walking. Instrumental activities of daily living are tasks that are not necessary for daily living but that help one live independently, such as managing finances, performing housework, and preparing meals.

TABLE 2-1 Types of Assistance Needed by Users of Long-Term Services and Supports

| Level of Need | Number of Activities for Which Help Is Needed | Typical Activities for Which Help Is Needed | Population (millions) | Percentage of Population Receiving Unpaid Help | Percentage of Population Receiving Paid Help |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | 1–2 | Getting out into the community and/or housework | 6.6 | 93% | 8% |

| Medium | 3–5 | Low level activities and preparing meals and/or managing medications and/or managing money | 3.0 | 92% | 14% |

| High | 6–8 | Medium level activities and bathing and/or dressing and/or transferring | 1.4 | 91% | 20% |

| Very high | 9–10 | High level activities and eating and/or toileting | 1.1 | 89% | 22% |

NOTE: Based on 2010 data from the Census Bureau Survey of Income and Program Participation.

SOURCE: Adapted from Kaye, 2016.

being fully met, while a survey of home and community-based services participants in six states (NASUAD and HSRI, 2016) found that 38 percent of those individuals said that the services they received did not always meet their needs and goals. The respondents to that survey said that their top need was for homemaker or chore services, followed by transportation and personal care services. They also reported needing more help with companion services, vehicle and home modifications, home health services, technology and equipment, home-delivered meals, and housing.

Community participation is a challenge for those needing long-term services and supports, Kaye said. While social isolation is usually associated with older adults, it is just as much a reality for working-age adults who use long-term services and supports. Among working-age adults, he said, only 12 percent of those receiving long-term services and supports work outside of the home, compared with 74 percent of non-users. Among adults of all ages, only 46 percent of users say they participate in any kind of leisure or social activities, compared to 86 percent of those who do not use long-term services and supports. And while 62 percent of users say they go out with friends and family, this means that more than one-third of users do not. Participation in community activities is “shockingly low,” said Kaye, with only 29 percent of those who use long-term services and supports reporting that they engage in community activities, compared with 58 percent in the non-user population. A survey of participants in home and community-based services in six states identified health limitations as the primary barrier to community participation, affecting 66 percent of the respondents, with transportation being the second most common barrier (NASUAD and HSRI, 2016). Cost, lack of accessibility and equipment, and not enough help were also cited as barriers to community participation.

In general, those individuals who have personal assistance workers are satisfied with the help they receive, though they do report some problems. The most common complaints are that the workers change too often, the consumer cannot choose or change his or her workers, and the workers do not do things in the way that the consumer prefers. Reliability, honesty, respect, and safety were mentioned as problems by a smaller percentage of consumers. Only 8 percent reported that their workers had inadequate training or were incompetent, and 5 percent said their workers did not know what help the consumer needed.

A Workforce Split Between Two Paradigms

To provide a framework for thinking about the workforce that provides long-term services and supports, Kaye briefly described the two major paradigms used for conceptualizing disability: the medical model and the social model. The medical model focuses on fixing, curing, and

treating disability, while the social model emphasizes living independently at home, participating fully in community life, having choice and control, and advocating for rights. Kaye said that he sees these two disability paradigms as being analogous to the situation in the world of long-term services and supports: at one end of the spectrum is the health care model, which aims to manage chronic conditions and prevent functional decline, while the social services model supports self-determination, promotes participation, and works to ensure dignity and respect. Both models, he added, aim to avoid institutionalization and enable individuals to live safely at home.

Kaye said there is also an analogous paradigm for the paid long-term services and supports workforce. One model features agency-employed, technically trained home health aides, often credentialed as certified nursing assistants or similar titles, while the other paradigm, which Kaye said is favored by the independent living movement, focuses on personal care attendants who are chosen by the consumer, work as independent providers, and may or may not be family members. The first model emphasizes the provision of health care–type services, while the second model emphasizes the communication and listening skills that are critical to understanding and following the consumer’s instructions.

The training for these two types of workers differs. Home health aides typically receive directed training using curricula developed by professionals, while attendants might receive no formal training, might receive their training from the consumer, or might receive training directed by the consumer. “There are many disability advocates and consumers who think of training requirements and certification requirements as a really bad thing,” said Kaye, largely because they fear a return to the medical model which takes away the consumer’s control, but also because they fear that training requirements might worsen the workforce shortage that many consumers already encounter by increasing the barriers to entry and to retention. Some consumers, added Kaye, do not want their workers trained at all, and while those consumers are in the minority, they do represent a viewpoint that should be considered.

A 2007 survey of consumers of long-term services and supports in Washington State, which largely relies on an independent provider model, found that 56 percent had difficulty finding workers when they had to replace a worker (Mann and Pavelchek, 2007). In 2012 the state increased its long-term services and supports worker training requirements, nearly doubling the requirements and adding continuing education requirements. Kaye said that this was thought to be a positive change. However, 42 percent of the workers subject to the new requirements failed the certification requirements, and another 24 percent passed but were late in doing so and thus had to stop serving their clients while waiting to take

the certification exam. Kaye said that during this time, consumers in the state reported that they experienced service disruptions and had difficulty finding certified workers to replace those workers who did not pass the requirements.

Additional issues with regard to worker training include whether the training model should be different for agency workers and independent providers and whether family members and other types of individual providers should be exempt from training, Kaye said. Similarly, there are the matters of whether training should be mandatory or voluntary, and whether consumers should be able to decide if they want their workers to have training or not or even choose what types of training their care worker receives from a list of options. Kaye said that additional subjects of debate include the content of training curricula, whether technical skills or consumer direction should be emphasized, and who has control of those curricula.

In conclusion, Kaye said that given that the population needing long-term services and supports has diverse needs and diverse chronic conditions, it is dangerous to try to pigeonhole individuals into a specific program based on their particular disability. Many of these individuals are poor or near poor, and unmet needs are highly prevalent among them, even for those participating in government-funded home and community-based services programs. Unmet needs, he said, are a major cause of low community participation and social isolation. As for the long-term services and supports workforce, consumers report problems with worker retention, choice, and control. Required worker training is controversial because it is seen by many people with disabilities and disability advocates as a return to the medical model of disability. “I want to urge people who are thinking about worker training to consider the trade-offs between requirements for training and barriers to workforce entry, which do seem to be worsened by requirements, and the trade-off between these requirements and the consumer’s desire for choice and control and the ability to hire independent providers, including their family members,” Kaye said.

GOVERNMENT PERSPECTIVE ON THE WORKFORCE PROVIDING LONG-TERM SERVICES AND SUPPORTS

Luis Padilla

Associate Administrator, Health Workforce

Health Resources and Services Administration

The combination of an aging population and a growing number of individuals with disabilities is increasing the demand for both licensed

and unlicensed health care workers to provide services which are often time-intensive and sometimes needed on a continuous basis, said Luis Padilla of HRSA.

Older adults and individuals with disabilities are among the nation’s largest health care consumers, said Padilla, and their care is financed primarily through Medicare and Medicaid. Because the demand for care is growing, there is a rising interest in innovative financing and delivery approaches that can improve health while reducing costs. “These fiscal trends are impacting demand for competent health care workers and influencing the skills and education those workers should possess,” said Padilla. “Emergent strategies to improve quality and manage care and cost will demand new skills, especially [for] those [working] in long-term care.”

The majority of older Americans—75 percent of those ages 65 and older—have at least one chronic condition, Padilla said, and they rely on health care services far more than other segments of the population. “This generation of older adults will be the most diverse this nation has ever seen, with more education, increased longevity, more widely dispersed families, and more racial and ethnic diversity, making their needs for health care services much different than previous generations,” Padilla said, adding that the health care workforce’s continuing medical education is inadequate to meet those changing service needs. At the same time, individuals with disabilities are less likely to receive recommended care and are at higher risk for poor health outcomes. The absence of professional training on disability competency issues is one contributing factor, said Padilla.

The Workforce Landscape

HRSA’s mission is to improve health and achieve health equity through improving access to quality services, a skilled workforce, and innovative programs, said Padilla. To serve that mission, HRSA considers the multiple factors that produce an effective workforce in health care delivery. “We think about who is the workforce and what are the team-based models of care that result in access, quality, and cost-effectiveness,” Padilla explained. This thought process leads to such questions as how to support recruitment, retention, and distribution, and how to educate the workforce.

Broadly speaking, Padilla said, the long-term care workforce comprises licensed professionals, paraprofessionals,3 and informal caregivers. Licensed professionals include physicians, nurse practitioners, home and

___________________

3 “Paraprofessionals” are also referred to as “direct-care workers.” In this Proceedings of a Workshop, the term used by the speaker is the term that is used in the proceedings.

community health services providers, agency directors, registered nurses, licensed practical and vocational nurses, licensed social workers, physical therapists, and occupational therapists. Paraprofessionals are health aides, nursing aides, orderlies, attendants, personal care and home care aides, and independent providers employed directly by consumers and their families. The majority of paraprofessionals work in nursing homes and assisted living facilities, though the number who provide in-home support and health-related services is increasing. Padilla said that estimating the size of the paraprofessional workforce is difficult because so many are employed directly by consumers and thus might not get counted in surveys. Informal caregivers, he added, provide approximately 75 percent of the long-term care to older adults and their families.

Several sectors of the health care workforce have shortages. One concern for HRSA is the shortage of primary care providers, the demand for which is expected to grow significantly as the U.S. population ages. “We need to change the health care delivery system, or else the primary care supply will be inadequate to meet this demand by 2020, which is only a few years away,” said Padilla. The shortage is projected to be greater than 20,000 primary care providers, he added. Increasing the use of nurse practitioners and physician assistants can alleviate this shortage by enabling alternative and innovative models of care, he noted, but it will not eliminate the shortage. On the other hand, the supply of registered nurses and licensed practical nurses is expected to outpace demand nationally by 2025, but this projected national surplus masks what Padilla called a massive distribution imbalance at the state level. For example, 22 states are expected to have a shortage, not a surplus, of licensed practical nurses by 2025. Complicating the matter further, some sectors of the health care workforce have proportionately fewer providers living in rural areas, regardless of education and training. In addition, said Padilla, turnover rates for paraprofessionals are high, increasing the burden of training new professionals to meet the growing demand for services.

Ongoing Work in HRSA’s Bureau of Health Workforce

The vision of HRSA’s Bureau of Health Workforce is to make a positive and sustained impact on health care delivery for underserved communities through a focus on education, training, and service. Its mission is to improve the health of underserved and vulnerable populations by strengthening the health workforce and connecting skilled professionals to communities in need. “We like to think of it as the education-to-training-to-service continuum,” Padilla said.

To realize its vision and accomplish its mission, the Bureau hopes to leverage its institutional grant program, scholarships and loan repayment

programs, and support for service and retention programs in combination with the research capability of the National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. “We are encouraging community and academic partnerships, inter-professional education and training, and utilizing a research and data approach to our programming and investment of our funds,” explained Padilla. The Geriatrics Workforce Enhancement Program4 (GWEP) is an example of this approach. This program focuses on integrating geriatrics and primary care to address the needs of older adults, their families, and caregivers at the individual, community, and population levels. The program currently has 44 awards with a total of more than $35 million supporting the efforts. These grants, said Padilla, encourage the engagement of families, patients, and caregivers to improve the quality of care and health outcomes, and the program explicitly requires partnerships with community-based primary care sites and community-based organizations.

The partnership between New York University’s Rory Meyers College of Nursing and the Montefiore Health System is one example of the 44 GWEP grantees. This partnership is providing newly discharged patients with supportive health care so that they can recover and recuperate at home. Another participant in this partnership is the Regional Aid for Interim Needs (RAIN) program, a community-based organization that serves older adults through 12 senior centers, Meals on Wheels, and a licensed home care services agency. In addition, the grantee is promoting inter-professional education that is focused on the unique care needs of older adults by training more than 600 health professionals and 1,000 of RAIN’s home health aides on how to provide care for adults with dementia, and it is teaching more than 60 community volunteers how to educate older adults on staying healthy through smoking cessation, exercise, good nutrition, and managing chronic diseases such as asthma, congestive heart disease, and diabetes. In addition, they implemented an innovative care coordination model that drives referrals from the Montefiore patient-centered medical home to RAIN. “This referral system facilitates communication between the community, the volunteers, and the patient-centered medical home, all of which help to improve care management and planning,” Padilla said.

HRSA also funds efforts that help the population of younger individuals with disabilities to live successfully in the community. The agency’s Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB) focuses on the unique health needs of women and children, including children with disabilities, through a system-of-care approach. This approach, said Padilla, organizes care into

___________________

4 For more information, see http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/grants/geriatricsalliedhealth/gwep.html (accessed September 2, 2016).

a flexible and coordinated network of resources. It also builds meaningful partnerships with families and addresses their cultural and linguistic needs, helping them to live, learn, and work in their communities. In addition, because many individuals with disabilities receive their health care through Medicaid, HRSA focuses on improving access to care for this population. The MCHB has two other programs specifically focused on the pediatric population: the Leadership Education in Neurodevelopmental and Related Disabilities Program5 and the Developmental–Behavioral Pediatrics Program,6 which focuses on preparing health professionals to work with children with autism spectrum disorders and developmental disabilities and their families.

HRSA is also actively seeking consumer input in its efforts to train and strengthen the workforce. When Padilla first joined HRSA, he said, he was surprised to find that so few of HRSA’s programs had consumers on their review boards. Before joining HRSA, he had worked at a federally qualified health center where consumers made up approximately half of the board members, making it one of only a few health systems that had consumers on their boards. One reason for the lack of consumer input at HRSA was that the grants HRSA reviews are highly technical and so the reviewers had been mostly professionals and academics. To remedy this, his office began promoting greater partnerships between communities and academia to facilitate dialog that includes consumers, and his office is also working to include more consumers who have backgrounds that provide them with the expertise to evaluate the complex grant applications. “What we’re hoping to accomplish is having greater partnerships between community and academics because that drive really should be coming from that academic institution that’s serving those communities,” Padilla said. “What we’re hoping to do is push more of that engagement, facilitate more of that dialogue.”

DISCUSSION

Minimum Wage and Overtime Pay Mandates

Fernando Torres-Gil of the University of California, Los Angeles, asked the two speakers for their thoughts on how the recent Department of Labor requirements mandating that the caregiving workforce be eligible

___________________

5 For more information, see http://mchb.hrsa.gov/training/projects.asp?program=9 (accessed September 12, 2016).

6 For more information, see http://mchb.hrsa.gov/training/projects.asp?program=6 (accessed September 12, 2016).

for overtime pay and benefits7 would affect the labor supply. Kaye replied that he is unsure what the result of this mandate will be. He said that his colleagues who advocate for individuals with disabilities recognize the actions to raise the wages of caregivers as fitting into the same movement for human rights and social justice that disability advocacy is in. Some of them also believe that a well-paid worker is a better worker. Kaye predicted that the transition between today’s system and the one that will evolve over the next few years will be difficult. “I think states are going to have to put more money into their Medicaid home and community-based services programs to deal with this, and I think there will be problems, but I think it is an issue that needed to be addressed,” he said.

Following up on Kaye’s comment, Padilla said that requiring workers to work in excess of what is determined to be a safe number of hours is likely to have a negative impact on the health care system. He also said that too often, not enough thought is given to how policies and programs affect individual caregivers. Referring to the quadruple aim of enhancing the patient experience, improving population health, reducing costs, and improving the work life of health care providers, Padilla said it will be important to identify the causes of high turnover and barriers to the retention of health care staff. “We do not know the factors that are driving that turnover, whether it’s wages, hours, or the practice environment, or maybe even the licensure requirements,” said Padilla.

Merging the Medical and Social Models of Care

Margaret Campbell of Campbell & Associates commented that the two presentations highlighted for her the disconnect she sees between the medical model and the social model of care. She said she was struck by Kaye’s statement that the main barrier to community participation is health limitations. “Where is the role of health promotion and wellness as part of this continuum of helping people live in the community and participate?” she asked. European countries, she noted, have a more integrated model that combines the medical and social aspects of care. She asked the two speakers if they see this integrated model as an urgent need for the United States. She added that she can understand why some consumers may want to personally train their caregivers to address their activities of daily living, but at the same time, she said, there could be benefits for a consumer working with a trained caregiver, such as the caregiver being able to provide an adaptive exercise program to prevent or reduce contractures.

___________________

7 For more information, see https://www.dol.gov/whd/homecare (accessed August 30, 2016).

Kaye responded that the integration of long-term services and supports into managed care will provide opportunities to address this disconnect. He suggested that community health workers8 could serve as a bridge between the medical and social models of care. However, he noted that not all consumers want to have caregivers who have more advanced training to, for example, prevent pressure sores. Padilla added that the nation is doing a better job of integrating services than it is of integrating care models, though both types of integration are challenging. One of the focuses of GWEP, he said, is to integrate and blend primary care and geriatric services and the medical and social models of care in a community setting. Time will tell, he said, how successful that effort has been. The main barrier to integration, he added, is a lack of information, which results from the fact that there still is not a free-flowing exchange of information that would indicate whether integrated models and services are effective. “I think you have pockets of where that is occurring,” he said, “but . . . even at the federal level and at the state and local levels there continue to be major gaps in information.”

Robyn Golden of the Rush University Medical Center remarked that this bifurcation of the continuum of care could create problems when it comes to having caregivers who are trained to work with people who will have some type of cognitive challenge as they age. This population of people is growing. One solution, she suggested, could be to keep the focus on providing person-centered and person-directed care, with the service plan informed by an assessment that integrates the consumer’s preferences and values.

Bruce Chernof of The SCAN Foundation said he believes that there is a gap in the middle of the care continuum—a gap between the medical and social models of care. He also agreed with Golden’s idea that letting person-reported outcomes and person-defined goals drive care and support plans would change care for the better. “I think that may be where the bridge [between the medical and social models of care] lies,” Chernof said. He also said that the medical system too often looks for a disease to treat, and if there is not one that can be treated, a person then becomes a problem. “That is a real problem in the medical system,” he said.

Michael Johnson of BAYADA Home Health Care commented that the U.S. medical community has held on tightly to disease classification,

___________________

8 The Bureau of Labor Statistics defines community health workers as those who “assist individuals and communities to adopt healthy behaviors. Conduct outreach for medical personnel or health organizations to implement programs in the community that promote, maintain, and improve individual and community health. May provide information on available resources, provide social support and informal counseling, advocate for individuals and community health needs, and provide services such as first aid and blood pressure screening. May collect data to help identify community health needs” (BLS, 2016).

as illustrated by the tremendous amount of effort that went into moving from the ninth version of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9) to ICD-10. Most other industrial countries, he added, instead use the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, which he said focuses on participation and addresses more closely what consumers want. He also suggested that if the nation’s care model moved toward the middle of Kaye’s care continuum, i.e., to a model that integrates the medical and social models of care, then this strategy could reduce the financial burden of the workforce shortage so that there would be enough money and enough workers in the system to meet the long-term services and supports demands of older adults and people with disabilities. “The intensity of services that I have to provide to one individual, because we wait until they are in an acute episode, could be spent on multiple individuals if we caught them earlier in the continuum,” said Johnson, and he said that this might also help reduce the workforce shortage. “I also believe that then we would have to focus less on the underserved because we will have figured out a way to serve everybody.” Given that point of view, he asked the speakers if they had any ideas on how to move to an integrated model in a meaningful way.

Padilla replied that the way the nation is training its health care workforce today does not leverage the capabilities of other paraprofessionals and community workers. There are many reasons for this, Padilla said, such as reimbursement policies and defending the turf of individual professions. HRSA, he explained, has little leverage in terms of the scope of practice regulations, which are set and implemented at the state level. HRSA is prepared, however, to provide grants to change practice regulations to support the more effective use of community workers and other paraprofessionals. What HRSA can do is focus on integrating training at the community and inter-professional levels, Padilla said, and he pointed to the Teaching Health Center Graduate Medical Education Program9 as an example of an effort to do just that. This program has resulted in 70 percent of the residents who are based in community-based organizations staying in those communities. “But more than that,” he said, “what seems to be happening in that environment is that the program is strengthening the infrastructure and capabilities of those organizations.” Padilla also noted that there is a community health center in the District of Columbia that has a medical school embedded in the center. That medical school is creating a pipeline that enables students, during both their medical education and residency, to gain experience in that community in order to develop a better understanding of that community’s needs

___________________

9 For more information, see http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/grants/teachinghealthcenters (accessed August 30, 2016).

and to learn how to collect population data that will help identify the most important social determinants of health that can then be addressed. Padilla said he believes this to be the ideal form of training for any health professional.

Workforce Training

Kate Tulenko of IntraHealth International asked Kaye to discuss what prompted Washington State to increase regulations for training. The increase in regulations, said Kaye, came about because the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) pushed strongly for greatly enhanced training requirements and certification. He said that when SEIU tried to pass similar regulations in California that would have required all caregivers to have 75 hours of training, disability advocates campaigned successfully to defeat the initiative. Whether the new regulations in Washington State reduced access is not yet clear because the state has not implemented quality measures that would indicate whether access to care or quality of care has been affected by these regulations. Kaye stressed the importance of involving consumers and disability advocates in any discussions prior to implementing increased training requirements.

Chernof commented that what gets lost in this discussion is that some of these needed changes are intended to benefit not only the people receiving services and support, but also the people providing them. He also suggested that one problem with developing a highly trained or certified workforce is that it assumes there is a one-size-fits-all model, but one size does not fit all in this case. For example, a community health worker who cares for people with moderate Alzheimer’s disease will not need the same training as someone who cares for people who have physical support needs and no cognitive issues. Kaye agreed that the idea of providing different types of training for different types of caregivers is a good one. What is needed, he said, is to determine the purpose of a training program and what information a caregiver needs to perform his or her job. His center at UCSF, for example, has created a modular online training curriculum that disability advocates like because it allows consumers to decide which modules their workers need in order to address their specific care needs.

Padilla said that he believes that the way the nation is training its health professionals today is antiquated, given the focus on licensing and board certification compared to how little attention is paid to community-based training—that is, training health professionals in the context of where services are actually delivered. GWEP, he said, is attempting to bring the community focus to training by closing the gap between what is happening in academic institutions and what is needed in the community.

Workforce Measures and Metrics

Padilla said that he and his colleagues are looking at all of HRSA’s programs to identify how they are connected and whether they will produce a workforce that meets the needs of the communities they are designed to serve. That effort entails examining programs to ensure that they are aligned with real outcomes and not just with the grant process, and selecting the right population measures and outcomes to judge whether these programs are generating meaningful outcomes. Kaye said that there is a need to define and select person-centered measures that can help achieve the desired outcome, something that the National Quality Forum is attempting to accomplish.

Priorities for Workforce Training

Amy York of the Eldercare Workforce Alliance asked the two speakers to list their top priorities for workforce training if money were not a limiting factor. Padilla said the three priorities for the Bureau of Health Workforce are diversifying the health workforce, distributing it effectively across the country, and transforming health care delivery. These priorities infuse all of the Bureau’s activities and funding opportunities. The health profession, he said, is “abysmal” with respect to health diversity and has been for the past 30 years despite powerful efforts to induce change. There are also more areas than ever with shortages of health professionals, particularly in rural and underserved areas where many of these populations reside. The nation is also struggling with integration of services and models. Given these three priorities, Padilla said, he would use the strategy of providing more population and community-based training outside of the academic environment for clinicians. “You need to do what you need to do in terms of critical care medicine and inpatient rotations, but the bulk of the training for our health professionals should be in the community,” said Padilla, adding that those community systems that know their communities’ needs should determine the curriculum for that training. “Again, what I am hearing is graduates are not prepared to practice in the communities that we want them to practice in—underserved and rural—and that impacts aging and disabled populations,” said Padilla.

Kaye responded by commenting that at the individual level, the effective provision of long-term services and supports is mostly about the relationship between a worker and a consumer and that workers can serve many consumers and consumers can have multiple workers. The question, he said, is how to have the consumers and workers create better partnerships to inform how care and support are delivered. “It seems to me that people who thrive when they are receiving long-term services and

supports have a solid working relationship with their workers, and the workers stay in it for a long time because it is satisfying to them and they are getting what they want out of it,” said Kaye. “I don’t know how to do it, but how do you improve that? How do you make that happen more often than it does now?”

Fulmer ended the discussion by noting that the United States spends $1 trillion on hospital care and $4 trillion on all health care. “There are many people who would argue that we need to spend our money smarter, not necessarily have more,” said Fulmer, “and that will have such a dramatic impact on schools for children, roads, and [many other] things.”

This page intentionally left blank.