2

The Task of Pattern Recognition

EDUCATIONAL PREPARATION

Before presentations on the current state of training and the nature of the job for pattern evidence examiners, Jay Siegel (Michigan State University, emeritus) provided an overview of changes in the educational preparation for those entering the field of forensic science. He pointed out that forensic laboratories have traditionally sought students with a strong science background. In the 1970s, degree programs for forensic science emerged, but there was still a strong preference for science majors, notably in chemistry or biology. In the early 1990s, interest in forensic science exploded, and the number of universities with forensic science programs grew rapidly.

Siegel related that in the early 2000s, the American Academy of Forensic Sciences created the Forensic Science Education Programs Accreditation Commission (FEPAC) with the goal of developing rigorous standards for the education of students in forensic science. These standards dictate a curriculum with a solid base of science courses and 15 to 20 percent of coursework in forensic science. The specific requirements were developed with the recognition that most students would eventually work in the areas of drug analysis, trace analysis, firearms and toolmarks, and forensic biology, and that specializations in any other area would require additional curricula or training.1 Siegel reported that about 35 FEPAC--

___________________

1 The standards are at http://www.fepac-edu.org/sites/default/files/FEPAC%20Standards%2002192015_1.pdf [November 2016].

accredited programs in forensic science exist, which offer both bachelor’s and master’s degrees. Students in accredited programs receive a general coverage of forensic science issues and a review of different types of evidence analyses, according to Siegel, but there is not time to develop and assess specific skills, like pattern recognition, in a college curriculum. Such skill development will likely continue to be part of apprenticeship experiences or on-the-job training. Siegel expressed interest in developing tools beyond the receipt of a degree in forensic science to help identify people who would be successful as pattern evidence examiners.

NATURE OF THE JOB IN FORENSIC LABORATORIES

Jessica LeCroy (Defense Forensic Science Center) presented an overview of what pattern evidence examiners do on a daily basis, their job demands, and the skills required. She contrasted a formal definition of pattern recognition—“a cognitive process that matches information from a stimulus with information retrieved from memory”—with the job where examiners look for patterns and geometric shapes, commit them to memory, and then try to find the same pattern in another source. In the forensic community, pattern recognition is conducted on certain types of evidence (e.g., fingerprints, footwear, tire tracks, ballistics, handwriting, and toolmarks). The task is to simply compare patterns or details from an unknown sample to a known source.

LeCroy showed the audience pictures of fingerprint, tire tracks, and footwear samples. She noted that examiners are expected to look for details and define which areas are suitable to perform a comparison. In the fingerprint sample she showed, only one area could be used for comparison. Examiners use the information or pattern in the evidence from an unknown source to compare to a known source, which may come from a named individual or a database, to determine if there is sufficient similarity to make an association between sources. With fingerprint samples, according to LeCroy, examiners study ridges in the sample, looking at the details, shapes, and voids present in the patterns. Examiners have specialized equipment to aid in this task, which can include magnification tools and digital imaging systems to enlarge and enhance the details present.

Winfred Arthur, Jr. (Texas A&M University), asked why the pattern matching process is not automated and why a human is needed. LeCroy pointed out that some of the process can be automated, notably with fingerprints. An examiner can code details of an unknown and run a search within a database of standards. Some of the challenges with automation include incomplete databases (i.e., there are no standards entered that

would match) and search runs that result in “close but no match” outputs. LeCroy asserted that a human is needed to do the coding and decipher any close results. She said an examiner would consider, “Is there sufficient similarity that . . . additional comparisons [should be conducted], or is there sufficient dissimilarity that [source discounted]?” Siegel added that evidence submitted to forensic laboratories is often not in good condition: for example, fingerprint samples are smudged, or a bullet hit a rock after it struck a victim. There can be characteristics on the imperfect evidence that can be analyzed, but it is difficult to tell a machine to look for sufficient details for comparisons.

Because visually detecting shapes and patterns is important and sometimes examiners can look at samples for days to find them, LeCroy said critical attributes of examiners include the cognitive skills necessary to learn, retain, and recall information and the ability to focus for long periods. In her experience, she said, on-the-job training that requires a series of comparisons for long periods and casework with senior examiners can develop and strengthen these skills; however, starting with a foundation of skill and ability, notably visual acuity, makes the training process more efficient and successful. Melissa Gische (Federal Bureau of Investigation) agreed and has found in her role in the laboratory that the ability to see different patterns and detect slight differences in images is not something that can be taught easily.

LeCroy also pointed out the importance of memory to examiners. With tire tracks or shoe impressions, recall of a similar sample in another case can provide a starting point to search for the source. With fingerprints, the examiner is comparing an unknown latent print against multiple records; the process can be more efficient if the examiner can remember specific clusters of information and not constantly refer back as each new record is considered.

John Collins (Forensic Foundations Group) identified a set of core competences for forensic examiners. His characterization included attributes such as clarity of vision and ability to discern patterns, quality of decision making, ability to exercise self-restraint (e.g., avoiding assigning greater significance to something that is not justified), internal fortitude (e.g., ability to take one’s ego out of a decision as well as disagree with others when appropriate), and communication skills. Collins noted that examiners’ findings from their analyses need to be communicated to end users (practitioners, attorneys, and judges in the legal system). They should be communicated in a way that does not create confusion or ambiguity and does not assign more or less weight to the evidence than is justified. According to Collins, forensic examiners both perform scientific testing and serve as consultants on the results, and he thought consult-

ing abilities are currently underdeveloped. The task of providing expert testimony is discussed further in Chapter 4.

LeCroy pointed out that forensic laboratories currently do not have a mechanism to detect existing knowledge, skills, and abilities. Applicants are selected based on other criteria such as minimal educational requirements or relevant experience. The result observed by both LeCroy and Gische is that some of those hired successfully proceed through training and do well as examiners and some do not. Consequences are additional training costs and loss in productivity.

LeCroy said she would like to see tools developed to help measure the skills and abilities necessary to succeed as a pattern evidence examiner. She would also like to see policies and procedures developed and implemented that allow laboratories to use these tools in the hiring process. Gische agreed that having such tools would allow determinations on qualifications earlier in the hiring process before investments in training individuals for 18 months or longer are made. According to LeCroy, the forensic science community needs help validating the importance of visual acuity and related cognitive abilities to the job, determining whether existing tests (like the form blindness test discussed below) are reliable at measuring these skills, and determining the extent to which training can develop necessary skills and abilities.

HIRING AND TRAINING OF PATTERN EVIDENCE EXAMINERS

Maria Weir Ruggiero (Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department) shared her experiences with hiring and training examiners and talked about recent changes in her department’s recruitment and selection process. She reported that the minimal requirements for education or experience are either an associate’s degree in any of the specialized areas of photography, crime scene investigation, fingerprinting, and criminalistics or on-the-job experience in an agency working on crime scene investigations, fingerprint comparisons, or as a laboratory technician on automated fingerprint identification systems.2 The position of forensic identification specialist in the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department requires an incumbent to conduct crime scene investigations as well as friction ridge (fingerprint) comparisons.

___________________

2 Although the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department does not require a bachelor’s degree for the forensic identification specialist position, Ruggiero reported that 15 of the last 20 people hired for the position had a bachelor’s degree in science.

Hiring Examiners

In the past, according to Ruggiero, hiring practices included an appraisal of education and experience to confirm minimum requirements were met, followed by an oral interview that weighted 100 percent toward the hiring decision. In the department’s most recent recruitment cycle, Ruggiero reported the addition of a written exam to the process. The written exam covers reading comprehension, written expression, data analysis and interpretation, error analysis, and pattern recognition. Ruggiero focused on the pattern recognition component of the exam. She showed the audience samples of questions where the applicants were asked to identify the image most unlike the other three images in a set. She illustrated that these comparisons were challenging; it was not easy to see the subtle differences. Box 2-1 outlines the number of applications received and how many people met the minimum requirements and went on to pass the written exam. Those that passed the written exam were invited to an oral interview, and top candidates were invited to a second selection interview.

Training Examiners

According to Ruggiero, the latent print comparison training program in the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department takes approximately 12 months to complete. The program consists of lectures, demonstrations, required reading of relevant literature and technical manuals, and super-

vised practicum. The bulk of the program is the practicum where the trainees are required to successfully complete a minimum of 600 latent print comparison identifications or exclusions.

After successful completion of the training program, Ruggiero reported that the trainees undergo competency testing. The competency testing includes an analytic or technical component and a theoretical component. The technical component consists of eight previously performed comparison cases. To pass, trainees need to correctly identify or exclude all identifiable prints with no erroneous identifications or exclusions. The theoretical component includes a written test and a moot court session. To pass, trainees need to obtain a minimum score of 80 percent on the test and a satisfactory rating on the court session.

Ruggiero recalled that since 2009, the department has hired 23 examiners. Twenty of those hired successfully completed comparison training. In 2009, their lab started administering a form blindness test (see Box 2-2)

on the first day of comparison training. Ruggiero observed that over the course of recording scores from the test and monitoring progress in training, the results from the form blindness testing have indicated which trainees would likely excel at training, which would need more attention from the training staff, and which would struggle to complete the training program. Ruggiero said she was not surprised by this observation since, as discussed above, “the ability to perform friction ridge comparisons is dependent upon the examiners’ ability to recognize [and interpret] minute differences and similarities.”

RESEARCH ON PATTERN RECOGNITION AND DEVELOPING EXPERTISE

D. Zachary Hambrick (Michigan State University) posited that the core competency under consideration in this workshop discussion is visual attention and the ability to form and maintain a mental representation, even in the face of distractions. He acknowledged that there is a large literature in cognitive psychology on visual attention. Cognitive psychology, Hambrick explained, is the scientific study of memory and thought processes using behavioral and neural methods of discovery in order to better understand individuals’ intrinsic skills. At the workshop, four different researchers presented findings from their research on human expertise.

Lisa Scott (University of Florida) talked about training perceptual expertise and whether that training was transferable to other sets of stimuli. Bethany Jurs (Transylvania University) discussed how training for latent print examination helps develop the expertise necessary to see through distraction. Mara Merlino (Kentucky State University) reviewed the factors involved in forensic document examination. Mark Becker (Michigan State University) presented what is known about visual search for low-prevalence targets.

Training Perceptual Expertise

According to Scott, visual perceptual expertise is a critical component of expertise required of a number of professions and activities: for example, a Transportation Security Administration agent screening luggage for potential weapons, a radiologist looking for evidence of breast cancer, a geospatial analyst scanning satellite imagery and assessing damage after a hurricane, a forensic examiner who conducts fingerprint analyses—even a birding enthusiast searching for rare species. (Scott’s research group often uses bird stimuli in its studies.)

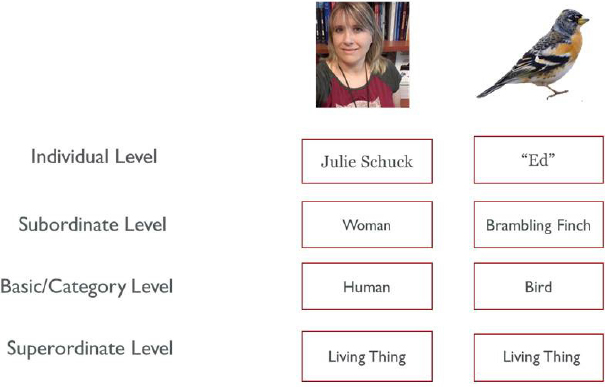

Scott showed the audience a picture of birds to illustrate how one’s

entry point of recognition is different depending on one’s level of expertise. She asked, “When you see an image, what is the first thing that comes to mind, what is the first label that you come up with?” A novice would look at the picture and identify the animals simply as birds. Someone with a little more experience or who lived close to the ocean might be able to identify the birds as a cormorant, a gull, and a pelican. An expert birder might recognize the birds as a double-breasted cormorant, a western gull, and a brown pelican. According to Scott, each advanced entry point requires the individual to process information at a higher level of specificity.

Scott pointed out that visual perceptual expertise has been investigated across a variety of domains in cognitive psychology and is recognized as an important attribute in how people process information. However, she noted that there is debate on the most important factors for training. Her research examines training factors that might increase perceptual expertise. Her training studies focus on trying to shift people from a basic level of processing, such as basic bird recognition, to the more specific pelican or brown pelican, and examine the best way to accomplish this. She highlighted the effects that were replicated in multiple studies.

Scott pointed out that adults typically process objects and faces at different levels (see Figure 2-1). In her research, she compares training at the basic level to training at the subordinate level. For the study she described at the workshop, the training was a computerized naming species task. An artificial species stimuli was created to help ensure that the effects after training were due to the training and not because of some prior knowledge participants had before training. Scott reported that the training took place over a 2-week period, and before training and after training, behavioral responses, electroencephalogram (EEG), and eye-tracking were recorded.

Scott explained that in the basic-level training task, participants were shown images of a species and had to distinguish whether the image was part of a “target” family or “another” family (i.e., yes/no response). For subordinate-level training, participants where shown images of a species and had to distinguish between a set of families and classify the image as one of the families (i.e., labeling response of 1, 2, 3, etc.). For each image response, the participant was given feedback on the correct answer. Scott reported that during the 2-week period, 6 training sessions were held with 25 blocks per session and 900 trials per session.3

___________________

3 Scott noted that the trials per block varied based on how many species/family participants had to learn. There were more trials in a five species/family block compared to a one species/family block. Difficulty was manipulated by changing the progression of how many species participants had to identify from each family during each training session. Increasing

SOURCE: Scott, L. (2016). Training Perceptual Expertise. Presentation at the Workshop on Personnel Selection in Forensic Science: Using Measurement to Hire Pattern Evidence Examiners, July 15, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Washington, D.C.

Her findings suggest that subordinate-level training was important for increasing perceptual expertise from pre-test to post-test. The study also found that training was robust to image manipulations (i.e., performance on degraded images did not decrease significantly) and that training gains generalized from trained exemplars to new exemplars within a family. Scott did not find that such training gains generalized to other families of artificial objects.

Scott informed the audience that EEG records are an added piece of evidence but not typically conclusive on their own. They are useful to show when things are happening in the brain and how fast one is processing information, on the order of milliseconds. In her study, EEG measures confirmed what was found behaviorally by showing significant difference in neural activity after training between stimuli trained at the subordinate compared to the basic level.

For future research, Scott expressed interest in understanding the effects of stress on perceptual expertise after one is trained in a relatively unstressful training paradigm. She asked, “Are there certain individuals who might be more resilient to those kinds of pressures?” She also said she wants to better understand the effect of context on the application

___________________

difficulty started with one species/family and worked up to five species/family. Decreasing difficulty started with five species/family and worked down to one species/family.

of expertise and the interaction between the perceptual information and contextual information. Returning to the birding example, she recognized that birders are not only learning labels, but also learning the context, such as habitats and sounds made.

Developing Expertise to See Through Distractions

Jurs recognized latent print examination and other types of impression analysis as examples of applied visual attention and perceptual expertise. She noted that fingerprint examiners conduct the task of comparing fingerprints in visually demanding environments. The fingerprints are often degraded and there is lots of information, but only some is useful for comparisons; yet they are still able to do this task. Jurs quoted John Vanderkolk from the Indiana State Crime Lab; when asked how examiners do this, he said, “You just have to learn to see through the noise.”

Jurs differentiated between two different types of “noise.” One is internal noise, which refers to random jitteriness that exists within people and may produce changes in one’s decision criteria. The other is external noise, which refers to actual degradation of the fingerprint.

Jurs discussed a training study that investigated how fingerprint examiners’ visual systems change across the course of their training to allow them to do this very visually demanding task. The study had a training group and a control group. Both groups had no previous forensic experience and were tested across three different days about a week apart to establish a pre-, mid-, and post-measurement. For each test day, groups were given three experiments, and in each test, they had the same three experiments.4 The training group received instruction similar to the first 3 weeks of fingerprint training at the Indiana State Crime Lab. During the course of training, the technical matching task became progressively harder, with fingerprint samples embedded in more external noise.

For the test, Jurs explained, participants were asked to match fingerprints in two different conditions. A fingerprint would come on the screen, either in noise or non-noise, and then four potential matches would come up, and the task was to identify which of the four matched the fingerprint in the middle. “If the individual got the answer right, then the next print that comes on the screen would be lower contrast, so it would be harder to see,” she said. “If they got the answer wrong, then the image that came on the screen next would be of higher contrast; it would be easier to see.”

Jurs reported that for low-noise conditions, participants were very accurate by the third test; there was no difference in performance between

___________________

4 For the purposes of this workshop, Jurs presented findings from two out of the three experiments.

the groups, and people maintained very high accuracy. However, for high-noise conditions, the training group outperformed the control group, with significant improvement in the training group’s comparison efficiency by the end of training.

Jurs pointed out that even though the control group had the same behavioral improvement as the training group for low-noise conditions, the EEG data showed differences. For the control group, the neural activity between day 1 and day 3 increased. For the training group, neural activity between day 1 and day 3 decreased. Jurs acknowledged that the significance of increased or decreased neural activity could not be interpreted, but the data illustrate that something different was going on between the groups. She suggested that “training causes the development of perceptual mechanisms that differ from those resulting from just exposure to stimuli.”

Jurs reported that participants in both groups had difficulty with the high-noise conditions. However, the training group showed significant improvement by end of training, whereas for the control group, changes were not significant. Even in this short training study, Jurs found effects of training were arguably developing mechanisms that allowed participants to extract out the relevant information and disregard the irrelevant noise.

For future research, Jurs suggested comparing findings from the training group to fingerprint examiners with years of experience. She said she also would track development of other behavioral markers of expertise beyond noise reduction mechanisms across the course of training.

Extracting Information from Handwriting

Merlino discussed research to investigate the way that forensic document examiners extract information out of signature specimens and how they use that information to reach decisions about the genuineness of questioned signatures.

According to Merlino, two key concepts for forensic document examiners are that no two people write exactly alike, which is referred to as inter-writer variability, and nobody writes exactly the same way from one time to the next, known as intra-writer variability. When analyzing signatures, Merlino noted that document examiners recognize the range of variation that can exist and evaluate samples on the consistency of written features, such as the slant of the letters, the writing’s orientation to a real or imagined baseline, and the letter spacing. They look for the presence or absence of the features that they use for the comparison of the questioned and the known documents. They do side-by-side comparisons of the writings that they have. They identify significant differences and similarities, and then they determine whether they have a sufficient amount of writing

to decide whether or not features of a questioned writing are consistent with the writing habits of the person who produced the known writings.

Merlino presented research that involved eye-tracking technology to record the actual gaze behavior of forensic document examiners as they went about the task of evaluating signatures. Forty-nine fully qualified document examiners and a comparison sample of lay people participated. According to Merlino, the eye-tracking technology records the gaze behavior of participants by tracking the reflection of infrared light from their retinas. This allows the researcher to determine what feature the participant is looking at (fixation); how much total time the participant spends looking at that feature (fixation duration); what features of the questioned writing are being compared to the known writing (referral saccades, or the movement of the gaze from one place to another); the order in which the participant looks at the features (scan path); the total number of fixations on the writing features (fixation count); and the number and total duration of visits to particular areas of the questioned and known writings (visit count and visit duration).5

Merlino discussed one protocol where participants were allowed to consider four known signatures for as long as they wanted and then asked to determine whether a questioned signature was a genuine, disguised, or simulated signature; they were not allowed to say inconclusive, but they could provide a value of confidence. Merlino reported that forensic document examiners were statistically significantly better at making these calls than were lay participants across a set of 66 different comparisons. In addition, the research found that the number of years that the document examiner had been in the field was unrelated to his or her accuracy on those calls. Merlino pointed out that forensic document examiners, on average, spent a greater amount of time on their comparisons and used a greater amount of information than did the lay participants, as indicated by fixations counts, fixation durations, visit counts, and visit durations.

Merlino showed the workshop audience four images of scan paths from the eye-tracking system, one from a lay participant and the other three from professionals. She noted that the lay participant did a very cursory job of looking at the signature and doing the comparison. In the other three images, there was a greater number of fixations and referral saccades. She suggested that the professional examiners sought out more distinguishing characteristics of the signatures and spent more time look-

___________________

5 Merlino explained that a person sits in front of an eye-tracking system. Infrared diodes in the system shoot light into the retinas of his or her eyes, and the light is reflected off the retinas and recorded by the eye-tracking system to measure gaze behavior. Metrics captured include fixation count, fixation duration, visit count, and visit duration. Merlino pointed out that a visit specified an area on the stimulus, and a visit could be multiple fixations within that area of interest.

ing at them than lay participants. She also recognized that even among the qualified examiners, the scan paths indicated a great deal of variation in how examiners go about the visual task.

In another protocol, Merlino reported that single signatures of three different signature types6 were displayed on the eye-tracking screen for 1 second. Participants were asked to determine whether it was a genuine or a simulated signature. Merlino found that forensic document examiners were able to correctly indicate whether those signatures were genuine or simulated about 70 percent of the time on average. She expressed that the 1-second view was enough for experts to judge such characteristics as internal consistency, line quality, slant, and orientation to baseline. She posited that experts can form images in their minds in a 1-second view and subsequently work with those images.

Merlino and colleagues also gathered information about the training of document examiners by surveying the participating forensic document examiners. Training for the group of document examiners was approximately 2.5 years on average, and subsequent certification was important. Merlino listed favorable aspects of training identified by document examiners: quality materials, textbooks, publications, and actual cases, as well as exercise repetition and immediate feedback.

For future research, Merlino suggested additional studies to examine the facets of the job and better understand the goals of training in order to develop exercises tailored to meet the training needs.

Searching for Low-Prevalence Targets

Mark Becker pointed out that in many important real-world searches, targets are rare. For example, he referred to mammograms. The breast cancer prevalence rate is about 0.3 percent of the scans. Even though radiologists are trained experts, they miss about 30 percent of those cancers. He noted that research shows the prevalence rate (likelihood of a target being in the search) has a large effect on the probability of finding the target. When targets become rare, people tend to miss them more often than when they are common. In research he conducted, Becker found that when targets were present on 90 percent of the search arrays people did relatively well, but when the target was only present on 10 percent of the search arrays, the miss rate went up to 50 percent.

___________________

6 According to Merlino, text, mixed, and stylized are three different categories of signatures. A text-based signature is a signature where all of the letters or all of the letter forms can be read, as can the allographs within the signature. A stylized signature is essentially a mark that has no distinguishable characteristics to it, and a mixed signature has a combination of text and stylized signatures.

Becker pointed to two sources of errors. One is called the search error, which occurs when people search the display and never get to the target. Becker noted this happens quite frequently and is likely due to a lower quitting threshold. He posited that when targets are rare, people’s quitting threshold shifts and they search less of the display. The second source is an identification error, which occurs when people search and eventually look at a target but fail to identify it as a target. In research models of visual search, according to Becker, this error is “due to a shift in the decision criterion that’s being used to evaluate whether each item is a target or not.” Becker pointed out that eye-tracking technologies have been used to differentiate between these two types of errors and have shown that the occurrence of both types increases under low-prevalence search conditions.

He and his colleagues have tried various changes to the structure of a search task, while keeping rare targets, in order to identify ways to increase the probability of finding low-prevalence targets. But these efforts have not worked, so research in this area is looking at individual differences given the substantial variability in how well people have performed in these low-prevalence search tasks.

Becker said there is research trying to identify attributes that characterize people who are less likely to commit these errors and therefore are better at low-prevalence search tasks. He said his studies have found that “both types of errors are negatively associated with working memory capacity.” In other words, higher working memory capacity reduces the chance of error.

Becker introduced another study that tested for additional predictors of visual search accuracy in these low-prevalence tasks. In this study, measures were collected for four cognitive traits: (1) accuracy on a high-prevalence search, (2) working memory capacity, (3) vigilance (the ability to stay on task), and (4) attentional control. A personality inventory was administered to compare individuals on openness, agreeableness, introversion/extroversion, conscientiousness, and neuroticism.7 Becker found that all the cognitive traits were significantly correlated with search performance. Of the personality traits, conscientiousness and neuroticism did not correlate with accuracy in low-prevalence search, and openness and agreeableness were not significant predictors. The personality trait of introversion and the four cognitive factors all added significant predictive power to their regression model. Becker reported that their model was

___________________

7 Mark Becker reported using a 20-question survey, a shortened version of a longer personality inventory, with decent reliability to assess all five personality traits. See Donnellan, M.B., Oswald, F.L., Baird, B.M., and Lucas, R.E. (2006). The Mini-IPIP scales: Tiny-yet-effective measures of the big five factors of personality. Psychological Assessment, 18(2), 192-203.

able to account for over 50 percent of the variability in low-prevalence search performance.

Becker noted that research shows that people likely to perform better in low-prevalence search can be identified by a battery of tasks that are simple and quick to administer. He suggested, more generally, that an individual difference approach to measuring traits or attributes may be an effective way to identify people who would be likely to perform well at tasks that require the accurate detection of rare targets.

The study Becker presented used simplified stimuli in simple displays in order to control the image statistics. He illustrated a simple search display where people look for a T in any orientation (the target) among other connecting line segments that are not quite a T (e.g., an L or ![]() ).

).

For future research, Becker said he would like to determine if the results he found generalize to more complex stimuli. Additionally, he would like to examine whether individual difference measures could be used to identify the people who would benefit the most from training in visual search tasks.

This page intentionally left blank.