3

Industrial and Organizational Psychology

This chapter provides a background on industrial and organizational (I-O) psychology and on strategies for developing selection tests and for recruitment. Remarks from participants and formal presentations at the workshop have been integrated to keep similar topics and ideas together in this chapter of the proceedings.

S. Morton McPhail (Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology) provided an overview of the field of industrial and organizational psychology to attendees. He cited a definition used on the Website of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology: “The scientific study of working and the application of that science to workplace issues facing individuals, teams, and organizations.” He recognized that I-O psychology is part of the broader field of psychology but is differentiated by the context in which I-O psychologists study behaviors; they study human behavior in organizations.

Much of the research and work in the field has to do with understanding the nature of human behaviors in the workplace, McPhail explained. Often the goal is to improve aspects of employment such as (1) employers’ ability to select and promote qualified people, (2) employees’ satisfaction in their work, (3) human effectiveness and productivity, (4) leadership and management, and (5) the workplace in general. McPhail recognized that years of research in I-O psychology have provided knowledge that has brought improvements to many aspects of the workplace. In addition, methods for development and validation of tests have been applied to thousands of different professions. McPhail noted that the field of foren-

sic science can leverage the scientific knowledge and practical experience within I-O psychology to meet current and future needs of the personnel in forensic laboratories.

McPhail pointed to a list of competencies of I-O psychologists taken from guidelines for graduate-level education to illustrate the breadth of the field (see Box 3-1). He noted that three of these competencies are particularly relevant to the workshop: #9 criterion theory and development, #15 job analysis, and #22 personnel recruitment, selection, and placement. Each of these competencies represents knowledge of theories and techniques that are used to generate information to improve aspects of employment, as discussed in more detail below. Melissa Taylor (National Institute of Standards and Technology) pointed out that all of the com-

petencies listed in Box 3-1, particularly judgment and decision making, would also be useful to the forensic science community. McPhail agreed that many areas of I-O psychology could help. In addition to the consideration of selection tools, the community could get help with measuring and assessing training programs, ensuring reliability of work outcomes, and controlling for bias. These are all things that have been studied in the past in other contexts and could be brought to forensic science, he suggested.

ASSESSMENT FOR THE PURPOSES OF SELECTION

Dan Putka (HumRRO) noted that the benefits of good selection practices and assessments can include improved job performance, reduced turnover, reduced training costs, reduced accidents, reduced counterproductive behavior (e.g., theft, errors), enhanced legal defensibility, and improved applicant perceptions of the employer. Assessment as used in this workshop and in the field of I-O psychology as presented by McPhail implies many different methods and tools, Putka said.

Nancy Tippins (CEB) pointed out that different strategies to identify capable candidates can be used in different contexts and at different points in time, even within the same organization, and that there are a range of different types of selection assessments. For example, résumé reviews and unstructured interviews are considered assessments, as are tests and structured interviews. In some workplaces, one of these strategies may be sufficient. In other workplaces, several strategies for selection may be useful. For example, inventories of personality traits or tests of cognitive abilities in addition to an interview would provide information useful for selecting the best candidates from a number of applicants.

As discussed further below, any test that is used for selection purposes must be fair, and according to Tippins, citing Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, “job relevant and consistent with business necessity.” There is a well-defined process for developing a fair and appropriate selection test, she noted. The steps of this process include job analysis, test development, criterion development, validation, implementation of the test into recruitment and hiring practices, and technical documentation. Tippins stressed implementation is not an insignificant step and requires concerted attention. She added that documentation is important to record that the test was developed and validated in accordance with both legal guidelines and professional standards.

JOB ANALYSIS

According to McPhail, job or work analysis comes in many forms, such as task analysis, worker-oriented analysis, and competency analysis.

“The work analysis must be sufficiently detailed and complete to identify the key components of accurately defining the requisite knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics, and the performance demands of the work,” he said. He explained that a job analysis determines the nature of performing a task, a set of tasks, or a job and includes examining “the physical and social context of the performance and the attributes needed by an incumbent for such performance.”

Tippins pointed out that it is essential for I-O psychologists to understand the requirements of a job before developing selection tests or procedures. A job analysis or work analysis is part of the test development and validation process that is designed to identify what the job requires in terms of tasks performed and the knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics necessary to perform these tasks, as well as the environment in which the job is performed and any issues and contingencies that affect job performance. Frederick Oswald (Rice University) noted that one reason for understanding the context is the ability to distinguish between issues and requests relevant to selection and those more relevant to training or recruitment.

According to Tippins, before a job analysis is conducted, a project initiation meeting between I-O psychologists and organization leadership is held to confirm the goals of the project, identify any issues or constraints on the research or the intended selection procedures, and review the project plans. Putka acknowledged that it is the role of I-O psychologists to work with organizations and subject matter experts to assemble a list of tasks, identify those tasks critical to perform the job, and use knowledge developed in I-O psychology to identify a set of attributes relevant to those tasks.

In conducting a job analysis, Tippins reported that interviews or focus groups may be held with job incumbents, supervisors, and/or other subject matter experts. Often questionnaires are used to collect quantitative information from people who are very close to the job. These job experts typically are asked to rate the task(s) in terms of frequency of use and importance to job outcomes. They are also asked to rate the selected knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics on importance and the extent to which these attributes are needed upon entry to the job.

Tippins pointed out that “it would not be appropriate to test somebody [in a pre-employment selection program] on a skill or ability that is trained or required at some point after they’ve been on the job for a while.” Findings from a job analysis on critical tasks and necessary attributes of personnel are used to design and choose both the appropriate selection test and the criterion measure (defined below). For some jobs, off-the-shelf tests work fine. For example, she said, there are plenty of arithmetic tests, and one may not need to be developed. If a very special-

ized skill or area of knowledge is involved, a test designed to assess the skill or knowledge may need to be developed.

THEORIES AND TERMINOLOGY

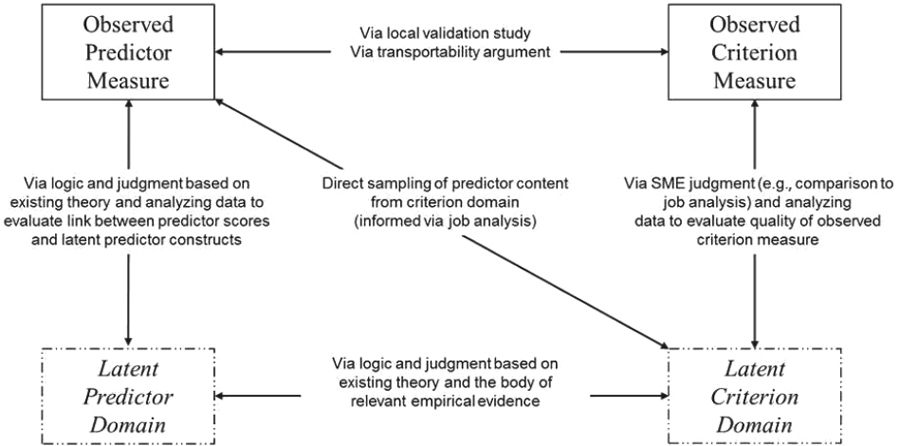

Presenters defined some terminology commonly used in the field of I-O psychology. The connections between some of these terms are illustrated in Figure 3-1.

Validity

McPhail presented a formal definition of validity from the Principles for the Validation and Use of Personnel Selection Procedures:1 “The degree to which accumulated evidence and theory support specific interpretations of scores from a selection procedure entailed by the proposed uses of that selection procedure.”

NOTES: SME = subject matter expert. Dashed lines around the lower boxes indicate domains where characteristics would be latent or unobservable. The lines and corresponding text indicate how the latent domains might be linked to observable measures.

SOURCE: Putka, D., and Tippins, N. (2016). Validation and Selection of Assessments for Hiring. Presentation at the Workshop on Personnel Selection in Forensic Science: Using Measurement to Hire Pattern Evidence Examiners, July 14, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Washington, D.C.

___________________

1 Published by the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, see http://www.siop.org/_principles/principles.pdf [November 2016].

McPhail emphasized that one does not determine whether a procedure or a test is valid or invalid. It is the interpretations from a procedure (e.g., test scores) that must be shown to be supported by evidence. He listed some conclusions that could be drawn by employers based on candidates’ responses or performance on a selection procedure:

- They have (or do not have) the minimum qualifications to perform the work.

- They have (or do not have) the requisite knowledge and skills to competently perform the work.

- They are more (or less) likely to perform the job better than other, competing candidates.

Validity, according to McPhail, is predicated on the evidence supporting the accuracy of these conclusions based on the test outcomes (e.g., scores).

Knowledge, Skills, Abilities, and Other Characteristics (KSAOs)

Tippins noted that KSAOs or KSAPs (knowledge, skills, abilities, and personal characteristics) are acronyms used often in I-O psychology. Putka explained that characteristics can include personality, interests, work values, education, and experience. He pointed to the job analysis as a way of identifying which KSAOs are critical to successful job performance and which are irrelevant. It is important to differentiate between KSAOs that can be picked up through on-the-job training or experience and those that are needed upon entry to the job (and thus important for selection purposes).

Observed Predictor Measure

Putka explained that an observed predictor measure is a test or an assessment used to evaluate attributes that cannot necessarily be seen, such as deductive reasoning or an assessment of conscientiousness. Predictor measures often represent samples or simulations of critical job tasks that are identified through a job analysis. These measures are developed to test for KSAOs that are critical to performance and needed at entry into a target job, and they are also known as aspects of the latent predictor domain.

Latent Predictor Domain

Putka noted the large body of research in psychology devoted to mapping out individual differences in cognitive, psychomotor, and physical domains. Unobserved individual differences in KSAOs are considered elements of the latent predictor domain.

Observed Criterion Measure

Putka explained that an observed criterion measure is an assessment of job performance, testing for outcomes that are actually required on the job. Examples of such measures include (1) ratings from a job incumbent’s supervisor or peers and (2) observed performance on a sample of critical work tasks (e.g., samples of fingerprints to match). Putka emphasized that the criterion measure should focus on an individual’s behavior and actions and not on job outcomes that would be beyond an individual’s control. I-O psychologists develop criterion measures to evaluate and validate selection measures (tests).

Performance Constructs and Latent Criterion Domain

Putka explained that performance constructs are dimensions of performance related to tasks (e.g., analytic and communications skills), context (e.g., teamwork), or counterproductive behaviors (e.g., dishonesty). Unobserved individual differences in performance constructs are considered elements of the latent criterion domain.

Transportability Arguments

In validating selection practices within an organization, Putka explained that transportability arguments could be used in situations where past research or past studies have examined similar jobs with similar predictor measures and similar job performance criteria. Arguments could be made that results from those studies will generalize to the similar situation.

TEST DEVELOPMENT

Liberty Munson (Microsoft Learning Experiences) is a psychometrician who ensures the validity and reliability of tests on a regular basis, providing her expertise to 125 tests annually. She oversees the development of certification exams. Such exams serve a different purpose than

selection tests;2 however, Munson pointed out that steps in developing these exams are fundamental to many types of tests. These steps can be broken down into nine development phases: (1) determining the need and rationale for a test, (2) creating a list of skills that could be measured on the test, (3) surveying subject matter experts to determine the importance of these skills and frequency of use, (4) creating and carefully reviewing test items for each skill, (5) field testing the test (beta), (6) revising test items based on feedback from the beta test, (7) setting the cut score (passing standard), (8) publishing or implementing the test, and (9) monitoring reliability and validity of the test. According to Munson, different sets of subject matter experts are consulted at each stage of the test development. They provide input for the list of tasks and skills that will be assessed through the job analysis. They usually write test items, and a different set of experts reviews the set of items (questions) for clarity, accuracy, and relevance, she explained. They also take the test as part of field testing and provide comments, and they provide guidance when setting the cut score.

Munson noted that during development, results from the field test are analyzed to review the quality of the test items to determine if they are too difficult or too easy and are able to differentiate between high and low performers. She noted that in field testing, it is important to consider the comments from subject matter experts in addition to the statistical analysis of the results, as these can point to issues that do not show up in the statistics. At this point, individual test items may be removed from the exam or revised. Munson emphasized that writing good test items is difficult. Depending on the content domain, subject matter experts or professional test writers create test items; professional test editors typically edit questions created by subject matter experts.

A final step in test development is setting a cut score or standard setting. According to Munson, certification exams generate a pass or fail result with determination of a minimum score that ensures one can do the tasks or skills the exam is designed to measure. Selection tests, on the other hand, are often scored in such a way that allows comparisons among candidates and helps organizations identify the best candidates for the job. Munson explained that a variety of different techniques can be used for standard setting, but many boil down to thinking about the minimal required competence of the target audience and the percentage of questions they should get right. Heidi Eldridge (RTI International), workshop participant, pointed out that on current certification exams for latent fingerprint examiners, a distinction is drawn between knowledge ques-

___________________

2 Munson pointed out that selection tests are used to predict potential performance. In contrast, certification exams are generally used to confirm that someone can actually perform the job tasks.

tions where a certain missed percentage is allowable and performance questions where no pattern identifications can be missed.

Munson acknowledged that test development, in general, avoids gatekeeping items (individual test items that must be answered correctly) to allow room for natural error in the process. Oswald confirmed that the reliability of a single test item is typically low. However, multiple test items can form a functional group measure to increase the reliability of assessing a specific skill.

Munson recognized that tests can lose their validity and reliability over time for a number of reasons (e.g., questions are leaked to potential candidates) and emphasized the importance of establishing a review process for the test performance. In some fields, it is challenging to maintain a reliable test as the environment and technology are continually changing. In more stable fields, maintenance is easier, but review still needs to be done. Munson suggested a revisit of the job analysis and test development every 5 to 7 years or more frequently if there are significant changes in the field. In addition, the statistical performance should be monitored as people take the test, and the agency or community should have a process in place to remove items that are no longer valid, reliable, or psycho-metrically sound and add new content. Test takers can also provide useful feedback via comments and surveys on what they like and do not like, which can be used to improve the test and/or test design and development processes.

VALIDATION PROCESS

According to McPhail, there are many validation strategies for developing and documenting evidential bases. Three have particular prominence in employment testing because they are specifically mentioned in the Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures:3 (1) criterion related, (2) construct related, and (3) content related. Putka and Tippins distinguished among the different validation strategies. They noted that all of the strategies involve establishing evidence that scores on a predictor measure are actually predictive of subsequent performance on the job or of some other criterion of interest (e.g., turnover, accidents, production, or counterproductive work behaviors).

In a criterion-related validation study, the evidence is a statistical relationship (e.g., a correlation) that is established between test scores (predictor measure) and the criterion of interest (often job performance measures). Tippins emphasized that the criterion measure needs to be collected in the same way using the same instruments for all people. In the

___________________

3 Available: http://www.uniformguidelines.com/uniformguidelines.html [October 2016].

validation of a selection test, job incumbents or applicants can be tested. However, if applicants are tested, often a longer waiting period ensues before accurate measures of performance can be made.

In a construct-related validation, according to Putka, existing theory and relevant literature are used to justify linkages between the predictor measure and criterion. Putka presented the example of Campbell’s model of performance determinants.4 This model depicts a set of distal determinants that help give rise to direct performance determinants. Distal determinants are attributes like a person’s ability, personality, interests, work value, education, training, and experience. Although Campbell’s model identifies a number of direct performance determinants, the field of I-O psychology has come to consensus on three primary determinants—declarative knowledge, procedural knowledge and skill, and motivation—that have been shown to have a positive relationship with job performance. Putka pointed out that declarative knowledge and procedural knowledge and skill tend to be malleable and therefore amenable to training, whereas attributes like ability and personality are viewed as more stable individual differences that are not as trainable. If a job requires certain ability or personality attributes going in, Putka suggested they should be considered at the selection or recruiting stage and not at the training stage.

In content-related validation, Putka noted that the predictor measure closely resembles what people do on the job. The evidence to link the predictor measure to the criterion is bolstered by judgments of subject matter experts. Tippins explained that subject matter experts are asked to judge the extent different KSAOs are needed to perform the task, as well as to judge the extent to which the test (predictor measure) measures critical KSAOs. She noted that relying on subject matter experts can make the validation process easier in some respects but more difficult in others. According to Tippins, subject matter experts usually know what the job requires in terms of task but may find it tedious or challenging to link KSAOs to the task and test. She noted that sometimes I-O psychologists will use professional test writers instead of job experts to make judgments about the relationships between KSAOs and the tests.

Oswald pointed out that the dichotomy is useful for understanding the differences between strategies, but in practice, organizations interconnect the different validation approaches. Tippins agreed and acknowledged that many organizations strive to continually accumulate evidence of validity. They may start out with a content-related validation study to

___________________

4 Campbell, J.P. (1990). Modeling the performance prediction problem in industrial and organizational psychology. In M.D. Dunnette and L.M. Hough (Eds.), Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology (vol. 1, pp. 687-732). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

justify the immediate use of their test. After it is implemented, they might collect applicant and performance data (for those hired) and then conduct a criterion-related study. Inevitably, they need to use the applicant data to adjust for the restriction of range that occurs in the predictor and criterion with the criterion-related study.

PROS AND CONS OF VALIDATION APPROACHES

Tippins highlighted the pros and cons of the different validation approaches and a number of things to consider before deciding how a test is going to be developed and validated for selection purposes. These considerations include predictive power/validity of interpretations, coverage of job domain, costs, time, staffing environment, personnel requirements, adverse impact and other legal risks, applicant reactions, and type of

return on investment study possible. Box 3-2 summarizes considerations for content-related and criterion-related validation strategies.

According to Tippins, a content-related validation study typically takes less time than a criterion-related validation study. Theoretically, both types of studies could be done in about the same amount of time, but in reality, Tippins opined that “it is a lot easier [and faster] to get a smaller group of subject matter experts together in a room to [make judgments] than it is to test several hundred people and collect performance data from their supervisors or their trainers.” In addition, content-related validation studies are usually less expensive than criterion-related validation studies. Tippins pointed out that smaller samples can be used in content validation. A sample that is representative of the various demographic groups for the job is needed, but it does not have to be as large as for criterion-related validation studies.

However, Tippins noted content-related validation is not useful in all situations. The Uniform Guidelines states that content validation approaches are not appropriate for measures of certain constructs, specifically calling out personality and intelligence. Tippins explained that as the construct being measured becomes more abstract or difficult to observe, appropriateness and legal defensibility of content-related approach diminish. In addition, she conveyed that a content validation study does not provide evidence needed to address fairness concerns and demonstrate that the test works equally well for all members of protected classes, primarily defined by race and gender.

PERSONNEL RECRUITMENT

In her workshop presentation, Ann Marie Ryan (Michigan State University) pointed out the importance of recruitment and how it feeds into selection. Recruitment is the process of getting people in the pipeline ready to have the skills and qualifications to be selected for the job and attracting them to apply. Today, through advances in communications and social media as well as increased networking, more people are exposed to any single job posting compared to a decade or two ago. The downside of this is the heightened possibility of many candidates without the requisite qualifications and fit entering the recruitment process.

Earlier in the workshop, McPhail emphasized that the goal of personnel recruitment should be the effective matching of the needs, preferences, skills, and abilities of job recruits and those of existing employees with the needs and preferences of organizations. Ryan reminded the audience that employers, when trying to get personnel selection right, should keep recruitment in mind and consider whether their recruitment efforts will return enough applicants of the right quality and skills to make informed

decisions on hiring. She recognized that some messages allow prospective applicants to screen themselves out (“self-selection”), which in some situations is good. However, she cautioned against messages that might inadvertently lead those who should not screen themselves out to do so. Employers must consider whether their message is appropriately screening-oriented. Does it make the job look too hard to get? Or does it give people good information so informed decisions can be made about the fit? Who does the message attract? This becomes particularly important in fields that are currently not attracting a demographically diverse group of people.

Ryan distinguished between external and internal recruitment. External recruitment involves hiring people from outside the organization. Internal recruitment refers to applicants from other jobs within the organization. There are benefits to internal recruitment: applicants know something about the organization and the job, and hiring managers can access information about their performance easier. It can also build morale by defining career paths. On the other hand, she said, relying too heavily on internal recruitment can lead to stagnation in creativity or improvements if fresh perspectives are not entering the organization or create significant vacancies in other areas of the organization.

Ryan asked the audience to consider the current situation in hiring pattern evidence examiners in terms of internal and external recruitment. She posed a series of questions: Is it a good balance? Are the pros and cons appropriately considered? Are people who are potential candidates getting appropriate information about what the job requires to make an informed decision to apply or not apply? Ryan pointed to issues of recruitment sources. In today’s networking environment, people get information about jobs through social networks and often from multiple sources,5 and employers have less control over their job descriptions and perceptions of their industry on the Internet and in different communities. She noted that private-sector organizations are starting to focus on the role of all their employees in recruitment—what messages are given to employees and what they share in their networks.

Ryan acknowledged that research shows that referrals from current employees are effective toward identifying more successful performers. However, it is also well established that reliance on referrals can result in greater homogeneity in the types of people in an organization. This can be a negative in situations that do not have a very diverse group of

___________________

5 Ryan reported that 73 percent of 18- to 34-year-olds found their last job through a social network, citing Medved, J.P. (2014). Top 15 Recruiting Statistics for 2014. Available: http://blog.capterra.com/top-15-recruiting-statistics-2014/ [October 2016].

employees, and as a result, an organization continues to end up with a very homogeneous group.

In his remarks, Scott Highhouse (Bowling Green State University) focused on what is known about getting the right personnel fit for a workplace. He introduced Schneider’s ASA model, which begins with a process of attraction where an applicant selects the workplace with the characteristics the applicant desires, followed by a process of selection wherein the employer selects applicants with the characteristics it desires, and lastly by a process of attrition when people leave the organization if they do not fit within it.6 Organizations generally want to limit the last stage as much as possible.

Highhouse conveyed that the current literature on attraction7 suggests that an organization’s recruitment information and messages lead an applicant to have an image of the employer. The field of I-O psychology approaches the employer image in terms of instrumental dimensions and symbolic dimensions. Instrumental dimensions are the tangible things, such as location, pay, benefits, and advancement, that people consider when looking at a job. Symbolic dimensions are subjective perceptions, for example, whether people perceive an employer to be innovative, dominant in the industry, sincere, competent, or other qualities. Highhouse emphasized that symbolic dimensions can be important for attracting applicants if they positively distinguish an organization from other workplaces even when the instrumental dimensions are the same.

In developing image dimensions, Highhouse suggested that employers examine competing organizations and determine how their image might differ from other potential employers, identify the instrumental and symbolic dimensions that distinguish competing workplaces, and then choose to emphasize those dimensions that provide a competitive advantage and attraction.

Highhouse recognized that attraction may not be an issue in forensic science. The issue may be avoiding misfit. A common approach to limit misfit and avoid unrealistic expectations is the realistic job preview. The approach often includes employee testimonials, video presentations, and/or work simulations to illustrate aspects of the job that are both favorable and unfavorable. He noted that areas with the potential to create discomfort for some people can be identified in a job analysis (discussed

___________________

6 For a description of the attraction-selection-attrition (ASA) model, see Schneider, B. (1987). The people make the place. Personnel Psychology, 40, 437-454.

7 This literature was recently summarized in a review, see Lievens, F., and Slaughter, J.E. (2016). Employer image and employer branding: What we know and what we need to know. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 3, 407-440.

above) or through critical incident interviews.8 Part of the selection process entails understanding the discomforts of a job and identifying candidates who would be less aggravated by these discomforts.9 Highhouse recognized that selecting applicants who are more tolerable of any job discomforts does not preclude redesigning the job to reduce discomforts.

PROFESSIONAL STANDARDS AND LEGAL REQUIREMENTS

As McPhail noted, in the United States, assessment in the employment context is governed by a broad array of legal and regulatory requirements intended to provide fairness, which various state and federal agencies enforce. Box 3-3 shows the statutes and enforcement agencies most likely relevant with respect to assessment and selection.

The bottom line of all these statutes and guidelines, according to McPhail, is that “employers may not discriminate on the basis of race/ethnicity, color, gender, national origin, religion, age, or disability in any aspect of the employment situation.” He emphasized that this requirement applies to all selection procedures and noted that any procedure that has disparate (adverse) impact10 must be shown to be valid. In the legal sense, “valid” refers to demonstrating that procedures are job related and consistent with business necessity. He stressed that for legal defensibility, the laws that govern selection are primarily associated with enforcement of fairness in employment selection and hiring, but they apply to any aspect of the employment situation, including promotions or transfers. Pre-employment selection was the initiating point and continues to be probably the single most common, he said. The defensibility comes from having done the validation research in a way that is compliant with professional standards, the Uniform Guidelines, and case law. For defensibility in a job analysis, he said, “You’ve sampled adequately, you’ve conducted the interviews, you’ve gathered data, you’ve applied reasonable scientific principles to the obtaining of facts regarding the interpretations you can make of the test scores, [and] the evidence supports that.”

___________________

8 Critical incident interviews involve asking job incumbents to identify situations on the job that were especially uncomfortable.

9 At the workshop, participants noted that the job of a pattern evidence examiner often requires staring at patterns and samples for days and occasionally puts people in situations where their judgment is questioned. These experiences may be too aggravating for some people, whereas others may find them satisfying or less egregious. See Bernardin, H.J. (1987). Development and validation of a forced choice scale to measure job-related discomfort among customer service representatives. Academy of Management Journal, 30(1), 162-173.

10 Disparate impact means that the proportion of successful candidates from one subgroup is substantially less than the proportion successful from another subgroup.

Ryan pointed out that the legal requirements are important because they constrain and define some of the things that can be done. However, more important are the professional standards for the I-O psychology community. They dictate finding the best, most accurate ways to predict who is going to be an effective employee.