7

Effective Collaboration for Cardiac Arrest

The recommendations from the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM’s) report described a range of high-priority actions that could elevate the resuscitation field. Collaborative action across numerous organizations and institutions has led to progress over the past few decades. However, more formalized and sustained collaboration will be necessary to further advance resuscitation science and cardiac arrest surveillance, translate research findings into widely used evidence-based treatments and care, and achieve better survival rates and outcomes across the United States (IOM, 2015). Recommendation 8 from the IOM report describes the creation of a National Cardiac Arrest Collaborative, which could be used to bring unity to the resuscitation field, define shared goals, and continue the momentum that was created following the release of the IOM’s report (see Box 7-1).

FROM THE IOM REPORT TO FORMAL COLLABORATION: EXAMPLES OF SUCCESS

Vicky Whittemore, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health

In the late 1980s, the American Epilepsy Foundation invited two epilepsy organizations—the Epilepsy Foundation and Citizens United for Research in Epilepsy (CURE)—to join them for a meeting to discuss

opportunities to partner in research funding and advocacy for epilepsy. The name of the coalition, Vision 2020, originated from the vision that the early member organizations had for how epilepsy should be treated and publicly accepted by the year 2020, said Vicky Whittemore. The prelimi-

nary goals of Vision 2020 were to provide the American Epilepsy Society1 with the patient and family perspective, advocate for research funding on Capitol Hill, and serve as a support network and source of information for the many advocacy organizations across the epilepsy community. Each year the members of Vision 2020 met at the American Epilepsy Society’s annual meeting to discuss priorities. Over the years, the coalition grew to include more than 30 patient advocacy organizations and federal agencies, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the Department of Veterans Affairs.

In 2010 the members of Vision 2020 came together with additional funders to commission an IOM study on the public health aspects of epilepsy. In 2012, the IOM released the product of the study, a report called Epilepsy Across the Spectrum: Promoting Health and Understanding (IOM, 2012). The IOM report featured six recommendations that called on Vision 2020 to take action in areas related to improving the delivery of care, expanding educational opportunities for individuals with epilepsy and their families, informing the media, coordinating public awareness initiatives, and expanding collaborations to further strengthen advocacy efforts.

Maintaining Momentum Following the IOM Report

Following the release of the IOM report, Vision 2020 continued holding its monthly conference calls and discovered that the member organizations enjoyed working together closely. Additionally, there were a number of common areas in which the member organizations could coordinate, share information, and support each other. At that point, Whittemore said, the members of Vision 2020 determined that they needed to reorganize themselves to better accommodate the expanded membership and to strategically implement the recommendations from the IOM report. The primary objective of the reorganization was to establish effective, efficient operations and a structure that would streamline priority setting and decision making, improve leadership and accountability, and maximize joint fundraising activities. The purpose of the fundraising would be to collect resources that could be used to support specific collaborative projects as well as staffing needs for the collaborative.

During the reorganization process, the members agreed to remain under the auspices of the American Epilepsy Society rather than establishing their own independent 501(c)(3) organization, noted Whittemore. The

___________________

1 The American Epilepsy Society is a professional organization that encompasses clinicians, researchers, and patient advocates who are all focused on clinical care and research for epilepsy.

members also agreed to rebrand the coalition as the Epilepsy Leadership Council. The leaders of the Epilepsy Leadership Council’s member organizations came together to develop a charter and operating principles that all the organizations could support, said Whittemore. There is a sliding scale for membership dues, which are based on the annual budget of each organization. Whittemore also noted that the American Epilepsy Society has been very generous by providing staff support as the Council got off the ground. Now that the Council is operational, it will begin developing proposals and seeking additional funding to support agreed-upon projects.

The core of the Epilepsy Leadership Council’s mission is “to serve as a mechanism through which organizations can work on shared goals and projects that will have a positive impact on the lives of individuals with epilepsy,” said Whittemore. The second part of the mission highlights a focus on “areas where working together produces greater efficiency and impact than working independently,” noted Whittemore. This mission encourages the member organizations to collaborate without duplicating the efforts of any one organization. Given the diversity of the types of organizations that belong to the Epilepsy Leadership Council, the members decided to establish a 12-member leadership board, which was meant to be fairly balanced across the types of organizations. Whittemore observed that since the reorganization the board has been functioning very well, with all of the board members having an equal voice regardless of the size of the organization they represent.

In 2015, the IOM hosted a dissemination meeting that focused on progress that had been made since the release of the report in 2012. For example, a new app and website dedicated to empowering individuals with epilepsy to seek more information had been released and was featured on websites of all members of the Epilepsy Leadership Council (Vision 20/20 Partner Groups, 2016). Additionally, the National Association of Epilepsy Centers had implemented an accreditation process for epilepsy centers, which was a recommendation from the IOM report. During the dissemination meeting, the Epilepsy Leadership Council also described how it has collaborated to develop plans and priorities for research, education, and advocacy activities across the epilepsy field.

Whittemore reflected on some of the challenges that have faced the Epilepsy Leadership Council as it has evolved, noting that the board members are all volunteers who are busy with full-time jobs, running their own organization, or doing both. Therefore, the volunteer work is often a secondary priority. One of the biggest challenges for the Epilepsy Leadership Council has been determining which comes first—membership dues/funding or developing project plans. “You cannot do projects or make plans without funding, but you cannot get funds without having

plans or projects,” said Whittemore. Priority setting across such a large and diverse group of organizations has also presented some challenges, said Whittemore, but, overall, the organizations have managed to agree on common priorities.

A number of lessons from the collaborative efforts of Vision 2020 and subsequently the Epilepsy Leadership Council may be beneficial to the resuscitation field, said Whittemore. The various organizations that participate in the collaborative are all there for different reasons. Thus Whittemore reiterated the importance of focusing on activities in which collaboration will lead to better outcomes. Having a neutral party to help facilitate discussion and keep everyone focused on selected priorities is helpful. Whittemore also noted that staffing is critical to the success of any collaborative, saying that it is important to have a dedicated individual tracking all of the pieces and moving things forward. Generally, the Epilepsy Leadership Council and its collaborative nature have been attractive to industry stakeholders, said Whittemore. Rather than having to work across multiple organizations to support a public awareness campaign, for example, the funder can interact with one central entity.

COLLABORATION AND NATIONAL QUALITY IMPROVEMENT EFFORTS IN STROKE

Mark Alberts, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center

Numerous commonalities can be identified across the trauma, stroke, and cardiac arrest fields, said Mark Alberts. For example, trauma, stroke, and cardiac arrest all occur without warning and have a limited timeframe for effective response and intervention, and they all require a multidisciplinary team to provide and improve care. Based on these similarities and the lessons that can be leveraged from trauma and stroke centers, Alberts hypothesized that “a national network of cardiac arrest centers will improve the care and outcomes of patients with cardiac arrest.”

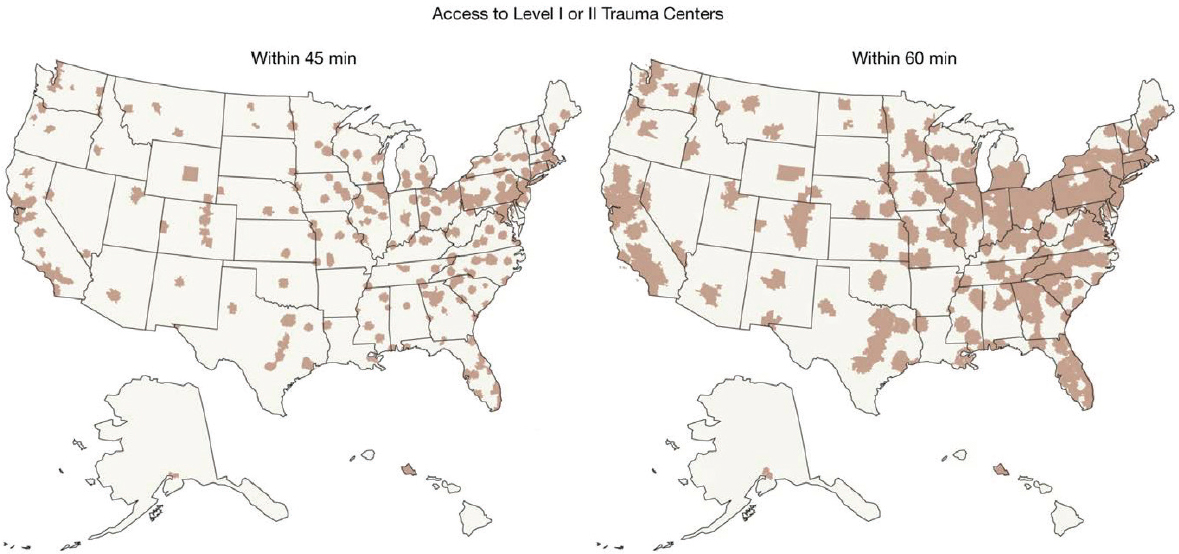

Since the development of trauma and stroke centers, studies have demonstrated improved patient outcomes. For example, the use of trauma centers has been associated with reductions in different causes of mortality (Nathens et al., 2000, 2001). Similarly, patients treated in designated stroke centers—primary or comprehensive—experience reduced rates of mortality when compared with patients treated in non-designated hospitals, with comprehensive centers linked to the lowest rates of mortality (Meretoja et al., 2010; Xian et al., 2011). The distribution of trauma and stroke centers has posed challenges for ensuring equitable access for patients (e.g., Figure 7-1) and will also be a concern for cardiac arrest cen-

SOURCE: Presented by Mark Alberts, July 12, 2016, A Dissemination Workshop on the Report Strategies to Improve Cardiac Arrest Survival: A Time to Act (citing Branas et al., 2005).

ters, said Alberts. The goal should be to create a system in which patients will have access to higher levels of care regardless of where they live.

Lessons from the Brain Attack Coalition and the Stroke Center Initiative

The Brain Attack Coalition is a multidisciplinary group of more than a dozen organizations and government agencies that is “dedicated to setting direction, advancing knowledge, and communicating the best practices to prevent and treat stroke” (BAC, n.d.). The Brain Attack Coalition falls under the auspices of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). Thus, NINDS provides a significant amount of support and infrastructure, such as meeting space and staff support, said Alberts. The Brain Attack Coalition is chaired by a former head of the stroke program at NINDS who volunteered to take on the role after retirement, said Alberts. The membership of the Coalition is determined by the parent organizations. Overall, there has been a sense of shared ownership and commitment. Although none of the organizations have veto power, noted Alberts, they all have a place at the table and provide input on the major decisions that the Coalition makes. To date, the Coalition has not accepted any sponsorship from industry sources. The organizations pay travel expenses two or three times per year for members to attend the Coalition’s meetings, which are held on the NIH campus.

Over the years the Coalition has supported activities related to public and professional education about stroke, such as NIH’s stroke scale. The Coalition provides a platform that allows the stroke field to speak with one voice and more easily coordinate with non-member organizations and agencies, such as the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, the Food and Drug Administration, and the Joint Commission. Alberts noted that recommendations from the coalition are widely supported and viewed as highly credible because of the diverse nature of the membership, which includes representatives from most of the major organizations in the stroke field. As with any large coalition, the decision-making process can be cumbersome, and competing priorities may lead to disagreements. However, the shared goal is to keep the process moving forward and come to a consensus on a final product that all of the member organizations will support.

In 2000 the Brain Attack Coalition launched an initiative to recognize hospitals that provide high-quality stroke care as designated stroke centers. This initiative galvanized the Coalition by giving it a concrete focus and structure. As the stroke center initiative got under way, the first challenge, said Alberts, was verifying that the hospitals were consistently meeting requirements related to staffing, infrastructure, care proto-

cols, and outcomes. The initiative experienced a tremendous boost when the Joint Commission began offering a formal certification for hospitals because there are certain expectations associated with Joint Commission certification, said Alberts. Once hospitals started to market themselves as certified stroke centers, other hospitals also sought certification, thus expanding the network of stroke centers in the United States. Subsequently, the Healthcare Facilities Accreditation Program and DNV GL also established certification programs for stroke centers. Today, there are more than 1,500 primary stroke centers and 200 comprehensive stroke centers nationwide (Alberts, 2016).

Since the implementation of the certification system, Alberts said that most states have developed a stroke system of care that includes a stroke triage or diversion paradigm. Some states used the Joint Commission certification as a basis for state certifications that allow emergency medical services (EMS) systems to alter their transport protocols, thus bypassing non-stroke-center hospitals when transporting a stroke patient. Following the development of regional triage protocols, EMS systems had concerns about bypassing nearby hospitals. However, Alberts and his colleagues conducted a survey in Chicago to determine whether hospitals were dissatisfied with the stroke triage protocols. He said that approximately a third of hospitals indicated they had no problem being bypassed and would rather not receive stroke patients because stroke was not an area of interest. If the resuscitation field decides to pursue a similar model, Alberts speculated there would be a comparable response from hospitals regarding cardiac arrest care in designated centers.

The diversity of EMS systems across the United States also presented some coordination challenges. In Illinois, which has 16 distinct EMS regions, local EMS systems were empowered to develop their own protocols, if they did not agree with the suggested triage protocol. However, all EMS systems were required to participate and report on metrics. As the regional triage protocols were implemented, there were concerns about overcrowding the stroke centers and extending EMS transportation times to the designated centers. However, the market essentially resolved those concerns, said Alberts. In urban areas, multiple hospitals became certified as primary stroke centers, in part because they wanted to be competitive. Therefore, problems with overcrowding and long transport times have not been observed.

Alberts offered the resuscitation field a range of advice on how to establish a national network of cardiac arrest centers. Reiterating the parallels among stroke, trauma, and cardiac arrest, Alberts suggested adopting a three-tiered system similar to those that have been used for trauma (i.e., Levels I, II, and III) and stroke (i.e., ready to handle comprehensive, primary, and acute stroke). Regardless of whether the arrest

occurs inside or outside of the hospital, he said that all designated centers should be able to provide a baseline of care. Alberts emphasized the need to develop a system that is flexible and also capable of tracking outcomes. Protocols should evolve based on available data and current standards of care, said Alberts. For example, endovascular therapy for acute stroke was not available in 2005, when the paper outlining the roles of comprehensive stroke centers was published. Thus the protocols had to be updated when that treatment became part of the care paradigm. Alberts restated the importance of collaboration as a pillar of success, saying that the resuscitation field would benefit from a coalition similar to the Brain Attack Coalition. When inevitable disagreements occur among coalition members, Alberts said, “always ask ‘what’s best for the patient?’ The answer will guide you to the best path forward.”

BREAKOUT SESSION REPORTS: ESTABLISHING A CARDIAC ARREST COLLABORATIVE

Tom Aufderheide, Richard Bradley, and Lance Becker, Planning Committee Members2

Tom Aufderheide, Lance Becker, and Richard Bradley facilitated the three breakout sessions that focused on establishing a cardiac arrest collaborative—Recommendation 8 in the IOM’s report (see Appendix A). The three groups considered potential stakeholders to engage, the definition and value of a cardiac arrest collaborative, barriers and opportunities to establishing such a collaborative, and potential next steps. Aufderheide, Bradley, and Becker all indicated that a number of breakout group members supported establishment of a national cardiac arrest collaborative. Aufderheide said that no one in his group believed there would a downside to establishing such a collaborative. Becker said many individuals in his breakout group favored using a collaborative to develop unified, patient-centered goals and messaging.

Individual participants in all three breakout groups suggested wide involvement that goes beyond the cardiac arrest community to include other medical specialties, consumer groups, industry, sports organizations, and many others (see Box 7-2). Bradley noted that the role of industry would need to be considered and defined in the early stages of

___________________

2 Breakout session presenters were asked to summarize the major ideas and opinions proposed by individual participants during their respective breakout sessions. Individual statements described below are not necessarily the position of the presenter and should not be interpreted as consensus statements from the breakout group as a whole or of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

planning. One workshop participant called for the inclusion of experts in marketing, branding, and communications, noting these are not necessarily areas in which researchers excel.

Defining the Purpose of a Collaborative

When defining the purpose of a collaborative, some participants in Aufderheide’s breakout group noted that the collaborative could pursue continuous innovation within the resuscitation field and achieve collective goals (e.g., improving patient outcomes) that may be unattainable through the separate actions of individual organizations or stakeholders. Some members of Bradley’s breakout group suggested that the collaborative focus on a shared agenda and collective goals, while building synergy. Other participants discouraged using the collaborative as a standards-setting organization. Becker noted that the organizers will need to have a discussion about definitions and clarify the distinction between the collaborative and collaboration and what those differences will mean for how the partner organizations interact.

Numerous benefits of the collaborative were noted in the three breakout groups. The collaborative could promote inclusivity, participation, and leadership by maintaining a neutral position and managing conflicts of interest and competition among member organizations, said Aufderheide. Some members of Bradley’s breakout group stressed the need to balance conflicts of interest across all participating groups, including industry. Other participants encouraged the collaborative to develop a set of toolkits and other materials for EMS systems and hospitals to use in deploying continuous quality improvement programs at local and regional levels. Aufderheide suggested that a collaborative could induce cultural changes related to the public, EMS systems, and hospitals and could also serve as a platform for funding opportunities. Bradley said the collaborative could have a greater impact on policy changes through synchronized messaging.

Individual participants in all three breakout groups identified many changes to forming a collaborative. Aufderheide and Bradley said that determining and coordinating membership, establishing governance and an effective mission, and developing operational processes would be among the primary hurdles. Bradley warned against becoming unduly bogged down with the development phase and administrative details. Aufderheide indicated that keeping the collaborative focused on shared objectives without impeding the work of individual organizations may also pose challenges. However, some members of Bradley’s breakout group saw this as a benefit, noting that the collaborative would allow several organizations to work in harmony and speak with one voice

without losing their individuality. Aufderheide, Becker, and Bradley, all remarked that developing a sustainable model with sufficient funding would be critical to success. Becker said that all participating organizations should contribute funding to support the collaborative, but a sliding scale could be used to ensure participation was not cost prohibitive to smaller organizations.

Two breakout sessions discussed possible short- and long-term goals and initiatives for the collaborative. Becker and Bradley both noted that one short-term goal could focus on public education to overcome the culture of inaction and increase rates of bystander cardiopulmonary resusci-

tation (CPR). Some breakout group participants also suggested setting a goal to improve EMS performance by more broadly adopting evidence-based practices. Becker said that expanding dispatcher-assisted CPR is a short-term goal that could have a marked effect in many communities. He also noted that, although surveillance would be a major long-term goal, discussions about how to conduct surveillance should happen in the short term. One workshop participant suggested the formation of subcommittees or task forces to tackle specific goals or areas, noting that the combination of goals and the recommendations from the IOM report may be too much for one group to solve. Furthermore, the collaborative could develop regular reports on the state of cardiac arrest and cardiac arrest care in the United States that also set national priorities for improving care, said Bradley.

In terms of long-term priorities, Bradley suggested working toward a national cardiac arrest registry that encompasses both EMS and hospital care. The registry could set goals and test programs to sustain and expand gains in bystander CPR rates and survival rates with good neurological outcomes. Becker called for establishing cardiac arrest as a reportable condition and suggested that the collaborative could play a role in advocating for updated diagnostic and billing codes. Another long-term priority, reported Becker, could be to adapt the Brain Attack Coalition model and develop a three-tiered designation system for hospitals that provides high-quality cardiac arrest care from basic to advanced levels.

Next Steps in Building a National Collaborative

Individual participants in Aufderheide’s group proposed two alternate strategies for next steps. The first option was to convene a relatively small group of representatives from key organizations (10 to 20 individuals) to initialize the planning phase of the collaborative—discussing funding models and membership, considering operational structures, and developing preliminary objectives. However, some breakout session participants expressed concern about transparency and lack of inclusivity with this approach.

The second option involved hosting a planning meeting with the key organizations and offering an opportunity for commentary and input either in real time or following the meeting for stakeholders not at the planning meeting. A few attendees urged organizers to hold the planning meeting within 3 to 6 months of the IOM’s dissemination workshop to continue the momentum, define the structure of the collaborative, and set short-term priorities.

Other participants from Becker’s session supported the idea of having

a smaller executive planning group with larger, more inclusive collaborative membership later.

A participant from Aufderheide’s breakout session offered five pieces of advice for initializing the collaborative:

- In the beginning, keep membership small. The membership will grow and evolve over time.

- Have a clear, discrete purpose and stay focused on that purpose.

- Do not try to achieve too many objectives at once. By choosing initial activities carefully, strategic investments can ensure success.

- Do not replicate efforts of member organizations or build new infrastructure where infrastructure already exists.

- Leverage the available expertise and resources of the member organizations whenever possible.

REFERENCES

Alberts, M. J. 2016. Stroke centers: A model for improving cardiac arrest care. Presentation at the Dissemination Workshop on the Report Strategies to Improve Cardiac Arrest Survival: A Time to Act, Washington, DC. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Activity%20Files/PublicHealth/TreatmentofCardiacArrest/JULY%202016%20Workshop/Alberts.pdf (accessed October 30, 2016).

BAC (Brain Attack Coalition). n.d. About us. https://www.brainattackcoalition.org/about.html (accessed October 3, 2016).

Branas, C. C., E. J. MacKenzie, and J. C. Williams. 2005. Access to trauma centers in the United States. JAMA 293(21):2626–2633.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2012. Epilepsy across the spectrum: Promoting health and understanding. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

______. 2015. Strategies to improve cardiac arrest survival: A time to act. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Meretoja, A., R. O. Roine, M. Kaste, M. Linna, R. Roine, M. Junteunen, T. Erila, M. Hillborn, R. Marttila, A. Rissanen, J. Sivenius, and U. Hakkinen. 2010. Effectiveness of primary and comprehensive stroke centers: PERFECT stroke: A nationwide observational study from Finland. Stroke 41(6):1102–1107.

Nathens, A. B., G. J. Jurkovich, P. Cummings, F. P. Rivara, and R. V. Maier, 2000. The effect of organized systems of trauma care on motor vehicle crash mortality. JAMA 283(15):1990–1994.

Nathens, A. B., G. J. Jurkovich, and R. V. Maier. 2001. Relationship between trauma center volume and outcomes. JAMA 285(9):1164–1171.

Vision 20/20 Partner Groups. 2016. My seizures, know more. http://www.myseizuresknowmore.com (accessed October 5, 2016).

Xian, Y., R. G. Holoway, and P. S. Chan. 2011. Association between stroke center hospitalization for acute ischemic stroke and mortality. JAMA 305(4):373–380.

This page intentionally left blank.