1

Introduction and Context

Since Cohen and colleagues described recombinant-DNA (rDNA) techniques in their seminal 1973 publication (Cohen et al., 1973), humans have been able to directly manipulate gene sequences in organisms. The manipulation of DNA led to the development of new products; early examples include synthetic human insulin and virus-resistant squash. In the United States, it also led to the development of a new regulatory framework to oversee the introduction of these products into commerce and into the environment.

The Coordinated Framework for Regulation of Biotechnology (hereafter referred to as the Coordinated Framework) was finalized in 1986, a little more than a decade after rDNA techniques had first been used successfully and at a time when few products from such techniques were in commercial use. It was the U.S. government’s policy “for ensuring the safety of biotechnology research and products” (OSTP, 1986:23303). In the notice announcing the policy, the Office of Science and Technology Policy (in the Executive Office of the President) stated that “[e]xisting statutes provide a basic network of agency jurisdiction over both research and products; this network forms the basis of this coordinated framework and helps assure reasonable safeguards for the public” (OSTP, 1986:23303). The existing statutes pertained to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), and the authorities granted under those statutes provided regulatory oversight jurisdiction for one or more of those federal agencies for all existing or foreseen biotechnology products at the time.

IMPETUS FOR THE STUDY

Between 1973 and 2016, the ways to manipulate DNA to endow new characteristics in an organism (that is, biotechnology) have advanced. Genetic engineering—the introduction or change of DNA, RNA, or proteins by human manipulation to effect a change in an organism’s genome or epigenome—originally relied on the use of a second organism (often a bacterium) as a vector to introduce a desired genetic change into the organism of interest. However, biolistic particle delivery—also known as the gene gun—was developed in the 1980s and can insert genetic material into the organism of interest without the use of a vector organism. Genome engineering employs

a direct and precise approach to whole-genome design and mutagenesis to enable a rapid and controlled exploration of an organism’s phenotype landscape. Advances in genome engineering are being fueled by two prevailing approaches: genome synthesis and genome editing. Whole-genome synthesis, which combines de novo DNA synthesis, large-scale DNA assembly, transplantation, and recombination, permits de novo construction of user-defined double-stranded DNA throughout the whole genome. Genome-editing techniques, which can make a specific modification to a living organism’s DNA to create mutations or introduce new alleles or new genes, advanced in the 2000s. These techniques—such as meganucleases, zinc finger nucleases, transcription activator-like effector nucleases, multiplex automated genome engineering, and clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats—also may obviate the need for vector organisms. The types of organisms that can be manipulated and the types of manipulations that can be made have increased considerably with these newer techniques. This increase has, in due course, expanded the types and number of products that could be developed through biotechnology. For its purposes, the committee defined biotechnology products as products developed through genetic engineering or genome engineering (including products where the engineered DNA molecule is itself the “product,” as in an engineered molecule used as a DNA information-storage medium) or the targeted or in vitro manipulation of genetic information of organisms, including plants, animals, and microbes. The term also covers some products produced by such plants, animals, microbes, and cell-free systems or products derived from all of the above.

Recognizing that “[a]dvances in science and technology . . . have dramatically altered the biotechnology landscape” since the Coordinated Framework was last updated in 1992 and that “[s]uch advances can enable the development of products that were not previously possible,” the Executive Office of the President (EOP) issued a memorandum to EPA, FDA, and USDA on July 2, 2015 (EOP, 2015:2). That memorandum contained three directives to the regulatory agencies. First, they were to develop an update to the Coordinated Framework to clarify their roles and responsibilities with regards to regulating products of biotechnology. Second, as parties to the Emerging Technologies Interagency Policy Coordination Committee’s Biotechnology Working Group (hereafter referred to as the Biotechnology Working Group),1 they were to formulate (EOP, 2015:3)

a long-term strategy to ensure that the Federal regulatory system is equipped to efficiently assess the risks, if any, associated with future products of biotechnology while supporting innovation, protecting health and the environment, promoting public confidence in the regulatory process, increasing transparency and predictability, and reducing unnecessary costs and burdens.

Third, they were to (EOP, 2015:5)

commission an external, independent analysis of the future landscape of biotechnology products that will identify (1) potential new risks and frameworks for risk assessment and (2) areas in which the risks or lack of risks relating to the products of biotechnology are well understood. The review will help inform future policy making.

EOP published an update to the Coordinated Framework (EOP, 2017) in January 2017, which was preceded by a draft version of the update and a National Strategy for Modernizing the Regulatory System for Biotechnology Products (EOP, 2016) in September 2016. These two documents responded to the first two directives of the July 2015 memorandum. The present report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine responds to the memorandum’s third directive.

___________________

1 The Emerging Technologies Interagency Policy Coordination Committee’s Biotechnology Working Group included representatives from EOP, FDA, EPA, and USDA.

THE COMMITTEE AND ITS CHARGE

At the request of the regulatory agencies, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (hereafter referred to as the National Academies) convened a committee of experts to conduct the study “Future Biotechnology Products and Opportunities to Enhance Capabilities of the Biotechnology Regulatory System.” Committee members were selected because of the relevance of their experience and knowledge to the study’s specific statement of task (Box 1-1), and their appointments were approved by the President of the National Academy of Sciences in early 2016. Committee members for National Academies studies are chosen for their individual expertise, not their affiliation to any institution, and they volunteer their time to serve on a study. The present committee comprised experts with backgrounds in diverse disciplines, including biotechnology regulatory law, agricultural and industrial biotechnology, risk assessment, social science, biochemistry, engineering, entomology, microbiology, and environmental toxicology. Biographies of the committee members are in Appendix A. The study was sponsored by EPA, FDA, and USDA.2

INFORMATION-GATHERING ACTIVITIES

National Academies committees often invite speakers to make presentations in order to gather information relevant to the study’s statement of task. The Committee on Future Biotechnology Products and Opportunities to Enhance Capabilities of the Biotechnology Regulatory System heard from 74 speakers over the course of three in-person meetings and eight webinars. All meetings and webinars were open to the public, streamed over the Internet, and recorded and posted to the study’s

___________________

2 The study was supported by a contract with EPA. Contract funding was provided by EPA, FDA, and USDA.

website.3 The agendas for the meetings, topics for the webinars, and names of invited speakers can be found in Appendix B.

The committee also submitted a request for information about research on future biotechnology products and regulatory science to 28 different federal offices (see Appendix C). It received responses from 17 offices, 12 of which had publicly available information relevant to the committee’s request. The submitted written responses with information can be found in the study’s public access file.4

As with all National Academies studies, members of the public were welcome to attend meetings in person or to watch them over the Internet. At the three in-person meetings, there were opportunities for members of the public to make statements to the committee. Written comments could also be submitted to the committee at any time during the study process.5 The comments were reviewed by the committee and are also archived in the study’s public access file.

Additionally, the committee reviewed several National Academies reports that addressed aspects of future biotechnology products. In particular, it looked at Industrialization of Biology: A Roadmap to Accelerate the Advanced Manufacturing of Chemicals (NRC, 2015), Gene Drives on the Horizon: Advancing Science, Navigating Uncertainty, and Aligning Research with Public Values (NASEM, 2016a), and Genetically Engineered Crops: Experiences and Prospects (NASEM, 2016b) for information about forecasts of future products derived from advances in biotechnology techniques and forecasts of any potential risks associated with these products. The committee gathered information from a broad range of references that included peer-reviewed scientific literature, as well as relevant reports from agency websites and news outlets, among a variety of other sources as indicated.

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

The next chapter begins with a general overview of the technical, economic, and social drivers that were influencing the types of biotechnology products being developed at the time the committee was writing its report. Chapter 2 also describes the classes of future products that the committee identified as particularly new and potentially challenging to the regulatory agencies. Examples of likely future products are given.

Chapter 3 reviews the roles and authorities of the different regulatory agencies that participate in the Coordinated Framework and describes the risk analyses the agencies used for biotechnology products. Chapter 4 analyzes whether the future biotechnology products that the committee saw on the horizon will pose different types of risks as compared to existing products and organisms. It also assesses what scientific capabilities, tools, and expertise the regulatory agencies may need to oversee these products relative to the current state of their scientific capabilities, tools, and expertise. Chapter 5 describes opportunities to enhance the capabilities of the biotechnology regulatory

___________________

3 Recordings of the presentations made to the committee at its meetings and webinars can be found at http://www.nas.edu/biotech.

4 The committee received written responses from the Army Research Laboratory Institute for Collaborative Biotechnologies, the National Science Foundation’s Division of Chemical, Bioengineering, Environmental, and Transport Systems, the National Science Foundation’s Division of Industrial Innovation & Partnerships, the National Science Foundation’s Division of Social and Economic Sciences, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the U.S. Department of the Interior’s National Invasive Species Council Secretariat, the Office of Naval Research, the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Biological and Environmental Research, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Agency responded to the request for information in its webinar presentation to the committee on July 25, 2016. Requests for the public access file can be directed to the National Academies’ Public Access Records Office at PARO@nas.edu.

5 For more information about the National Academies study process, see http://www.nationalacademies.org/studyprocess.

system, and the report concludes in Chapter 6 with the committee’s primary conclusions and recommendations, which are based on its review presented in the preceding chapters.

REPORT CONTEXT AND SCOPE

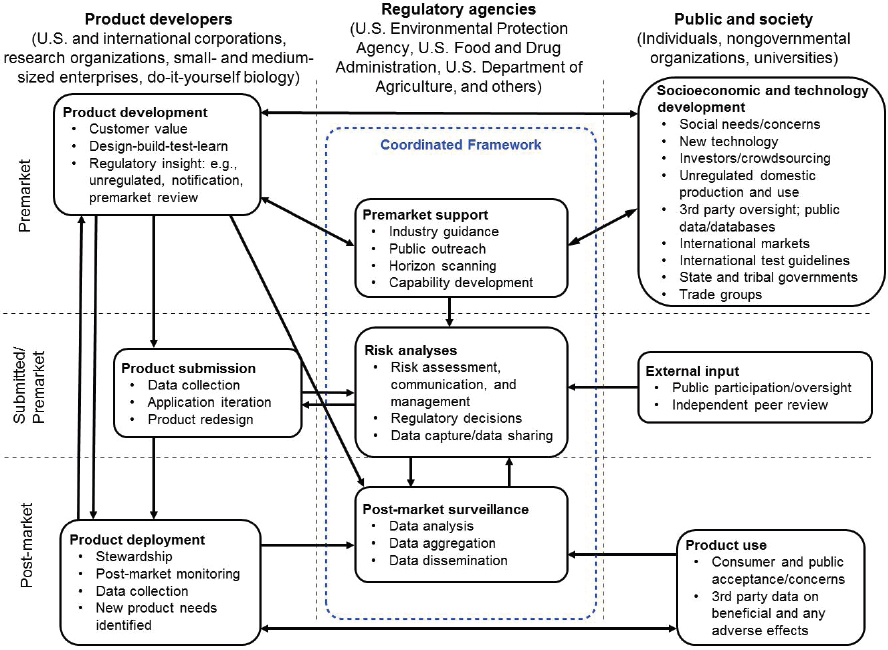

The committee’s work focused on future products of biotechnology and opportunities to enhance the capabilities of the regulatory system. With the diversity and number of future products anticipated over the next 5–10 years, the committee viewed the regulatory agencies, with their existing regulatory authorities granted under relevant statutes, as part of a large collection of interdependent parties involved in biotechnology-product discovery and development, science-based risk evaluation for potential entry into the marketplace, and oversight of biotechnology-product use. Figure 1-1 provides a high-level view of the many activities that can be a part of the overall regulatory landscape, including the different communities of interest and the relationship between the activities.

In the view of the committee, there are three primary phases of regulatory oversight:

- Premarket: Product development, prior to submission of a product for regulatory assessment or entry into the marketplace.

- Submitted/Premarket: Risk analysis for those products that require premarket assessments.

- Post-market: Product is available to consumers.

These three phases include multiple points of interaction between the regulatory agencies and technology developers, product developers, product consumers, and society as a whole.

For simplicity, the committee focused on three primary categories of actors or participants: product developers, whether these are traditional companies, small- and medium-sized enterprises, the do-it-yourself biology (DIYbio) community, or even individuals; regulatory agencies, including EPA, FDA, and USDA, but also other relevant agencies such as the Consumer Product Safety Commission and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration; and representatives of society and the public, including universities and other research organizations who might develop new biotechnology techniques, nongovernmental organizations that may be supporting or opposing specific biotechnology techniques and products, and international organizations, governments, and treaty authorities. There may be overlap between these categories, for example when a university or government laboratory is developing a technology that could itself be considered a product, either through transition of that technology to a startup or other company or through the direct use of that technology by the DIYbio community.

The interactions between the different participants in the biotechnology regulatory system vary based on the type of product, the phase of development or deployment, and whether or not a product falls under one or more statutes. For new products of biotechnology—that is, types of products whose uses have not previously been addressed by regulatory agencies—these interactions would usually be iterative in nature, with successive rounds of technology development, product development, product testing, public participation or oversight, and premarket or post-market oversight. The arrows between the different activities indicate possible interactions between parties and the types of information that are being shared—for example, submission of regulatory materials or decisions, informal communications at meetings and conferences, and formal communications through databases or public media.

The activities shown in Figure 1-1 will vary for different types of products and by the authorities and associated regulations of each agency. For example, FDA divides its product designations into premarket approval (which includes new drugs, Class III premarket-approval medical devices, and food additives), premarket notification (for products such as new dietary ingredients and

NOTES: The phase on the left vertical axis indicates the life-cycle phases of biotechnology products that are intended to be sold, distributed, or marketed across state lines. The top and bottom horizontal arrows reflect the interactions among entities developing and marketing future products and users or consumers of these products as well as interactions with entities developing new technology that may support development of future products. The three vertical columns and associated arrows reflect opportunities for interaction among developers, consumers, and interested and affected parties and regulatory agencies throughout the life cycle of a product. Note that the upper-right box also addresses domestic production and use of biotechnology products that are not intended to be sold, distributed, or marketed and therefore may fall outside existing statutes, with some exceptions (described in Chapter 3). Research organizations (including universities and government research laboratories) can serve as both product developers and members of the public and society, depending on the phase and type of their activities. The arrows connecting the various activities represent some of the primary interactions between the underlying actors and processes. Note that these arrows describe potential interactions, some of which may not be present in the current regulatory framework.

Class II Section 510(k) medical devices), post-market notification (applicable to structure or function claims for dietary supplements), post-market surveillance (for products generally recognized as safe and prior-sanctioned food ingredients, pre-1994 dietary ingredients, Class I medical devices, and cosmetic ingredients), and compliance with FDA standards (for example, pre-1972 nonprescription monograph drugs). For each of these categories, all of the FDA enforcement authorities (that is, seizure, injunction, criminal prosecution, warning letters, and publicity) apply once a product is marketed. The broad set of phases used in Figure 1-1 and the categorizations used below

are intended as a generalization that captures the different types of activities that might be present, independent of a specific agency’s statutory structure, and help highlight some of the challenges that will be faced in oversight of future products of biotechnology.

Product Premarket Evaluation

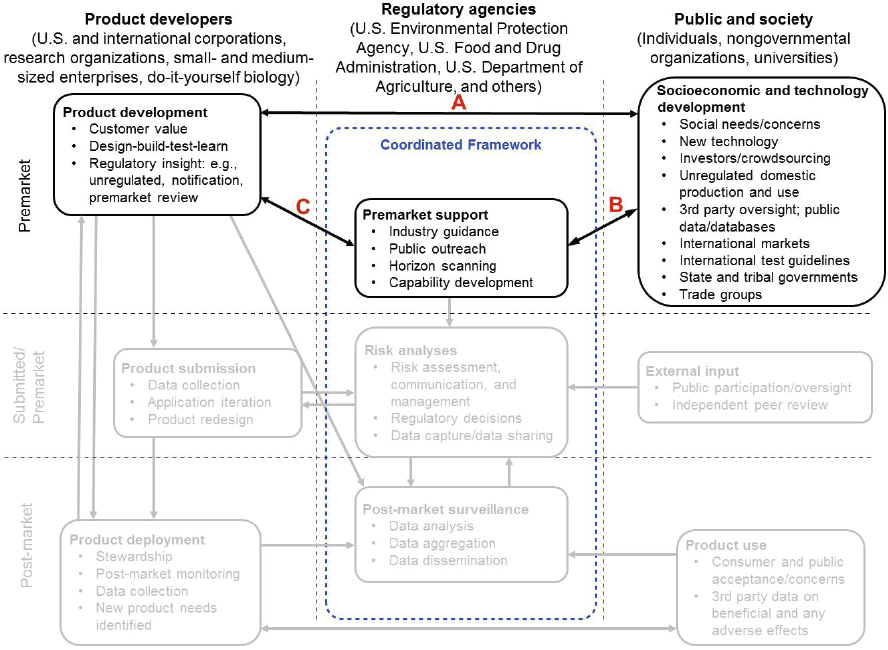

To illustrate the flow of information in the premarket phase of the regulatory system, one can consider iterations of technology development in which university researchers present information in papers or at conferences, while product developers try out those ideas in their laboratories (arrow between “Product development” box and “Socioeconomic and technology development” box, Figure 1-2, arrow A). The regulatory agencies may be involved as participants in scientific conferences (arrow between “Premarket support” box and “Socioeconomic and technology development” box, Figure 1-2, arrow B). The developer may initiate preliminary discussions with a regulatory agency and sharing of preliminary data to obtain advice about regulatory paths (arrow between “Product development” and “Premarket support” boxes, Figure 1-2, arrow C). The use of the “design-build-test-learn” cycle of product development may occur multiple times prior to submission of a formal application for use or experimental testing. In some cases, the developer may decide to return to the ideation phase or incorporate new technology that has appeared since the initial product development.

These discussions with the developer may lead to internal activities at the agencies that identify the need to develop insights and capabilities in preparation for anticipated regulatory decision making in the future. The agencies may decide multiple parties could benefit from a horizon-scanning exercise to inform risk-analysis approaches6 for these future products and hold public outreach meetings to gain insights and knowledge (arrows from “Premarket support” box to “Product development” and “Socioeconomic and technology development” boxes, Figure 1-2, arrows B and C).

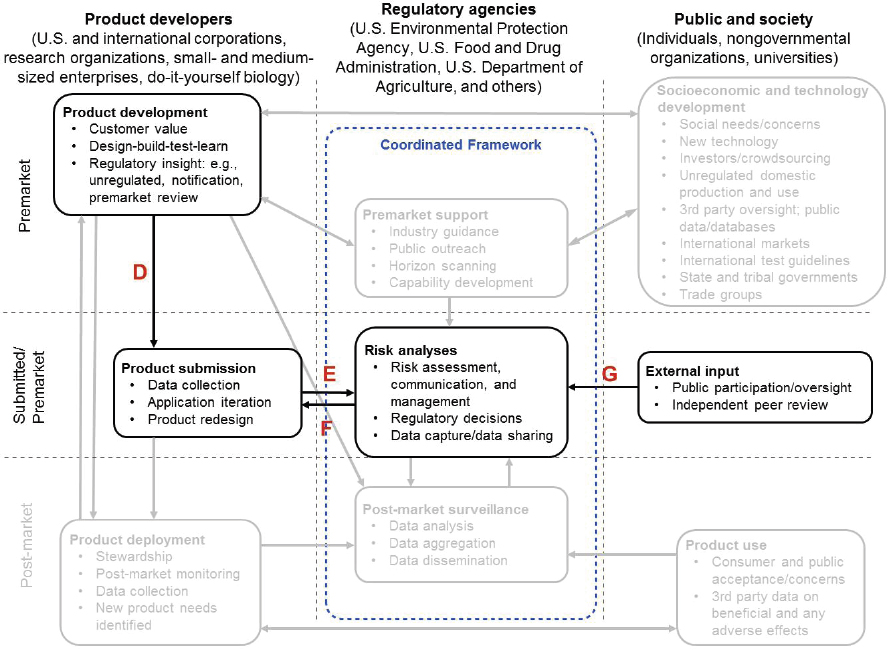

As product development matures, and assuming that the relevant statute requires a premarket evaluation, a product’s more detailed “premarket” information would be prepared (arrow from “Product development” box to “Product submission” box, Figure 1-3, arrow D) and submitted to the appropriate regulatory agency or agencies (arrow from “Product submission” box to “Risk analyses” box, Figure 1-3, arrow E). Submissions may involve requests for permission to do field trials to produce data in support of an application to enter the marketplace. Depending on the results of initial studies to support the risk analysis, the regulatory agency and the product developer may determine there is sufficient certainty in the risk analysis to proceed with a regulatory decision or they may conclude that additional information may be needed for the risk analysis (arrow from “Risk analyses” box to “Product submission” box, Figure 1-3, arrow F).

Depending on the familiarity and complexity of the new product, the agency may determine in

___________________

6 According to the Society for Risk Analysis, risk analysis includes risk assessment, risk communication, risk management, and policy relating to risk to human health and the environment, in the context of risks of concern to individuals, to public, private, and nongovernmental organizations, and to society at a local, regional, national, or global level.

some instances that public participation concerning the technology, the benefits of the technology, and its potential implications would be helpful to inform the risk analyses. The agencies may also engage external groups for peer review (possibly via a federal advisory committee) of a draft risk analysis (arrow from “External input” box to “Risk analyses” box, Figure 1-3, arrow G). For new product submissions that are less complex or are more familiar to the regulatory agency or agencies, these steps could be less involved or omitted.

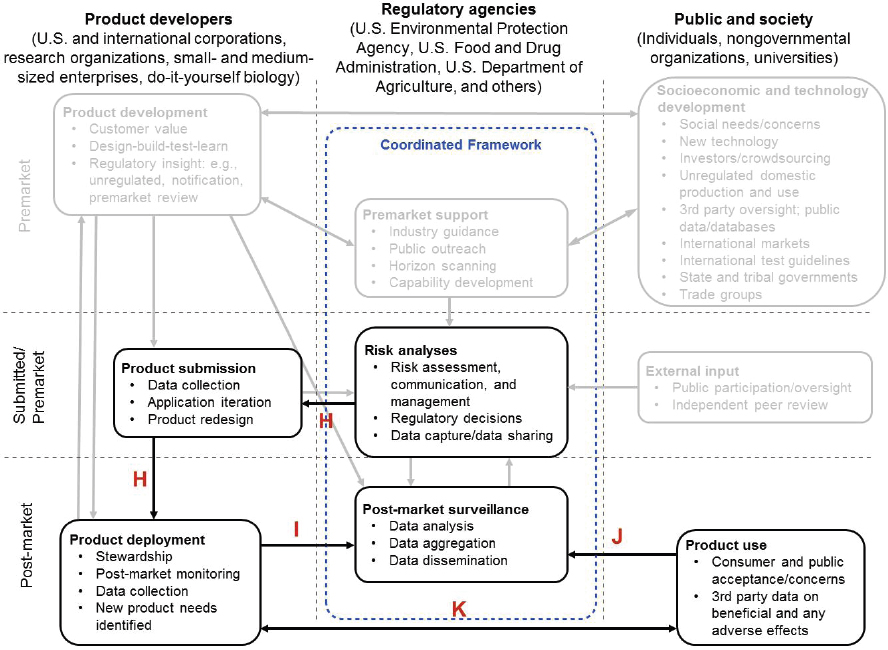

Assuming the regulatory decision supports entry into the marketplace, the developer can deploy the product consistent with the terms of the regulatory decision (arrow from “Risk analyses” box to “Product submission” box and arrow from “Product submission” box to “Product deployment” box, Figure 1-4, arrows H). At this stage, the product is available to consumers or users. Depending on the operative statute, if the developer wishes to expand the use pattern of the product, it may be required to submit additional data to the appropriate regulatory agency (or agencies) for evaluation. Depending on the agency and the results of the risk analysis, the developer may be required to generate post-market data to refine the existing risk analysis (arrow from “Product deployment” box to “Post-market surveillance” box, Figure 1-4, arrow I). Insights from consumers and users of the product, including data on product performance or unanticipated adverse effects (arrow from “Product use” box to “Post-market surveillance” box, Figure 1-4, arrow J), could also prompt an agency to reevaluate the existing risk analysis. Interactions between the product developer and users or other third parties could also lead to new product development within a company, new research

funded by government or other sources, or new discussions of social needs, benefits, and concerns (arrow between “Product deployment” and “Product use” boxes, Figure 1-4, arrow K).

Product Notification Alternative

A slightly different scenario is one in which no premarket approval is required. In this scenario, the initial premarket discussions described above could still occur, but in the context of premarket support it could be determined that, given the relevant statute for the product, a premarket evaluation is not required. In this case, the developer may only need to notify the appropriate agency that the product is entering the market and the developer has determined the product meets the relevant statute’s safety standard. In this scenario, if post-market data indicate unanticipated adverse effects associated with the product’s use, the appropriate regulatory agency could initiate a risk analysis to determine if risk mitigation is required.

Unregulated Products Alternative

In this scenario, initial premarket discussions with a product developer may determine that, given the nature of the product, it is not regulated under existing statutes. In this instance, the developer may voluntarily enter discussions with the relevant agency (or agencies) prior to entering the marketplace and subsequently rely on its stewardship program to determine if any changes to the product’s patterns of use are needed. There could also be instances where a product is being manufactured within a home for domestic use, with no intention to market, distribute, or sell the product over state lines. Depending on the nature of the product and the relevant statute, the product may not be subject to regulation, even though if it were manufactured by a company it could be subject to regulatory oversight. In this instance, the regulatory agencies could partner with third-party organizations to help support the development of stewardship programs.

Other Interactions

As noted in Figure 1-2 (arrow B), the regulatory agencies could interact with other parties on issues related to implementing the Coordinated Framework. For example, the agencies could work with various global organizations (such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) to develop international test guidelines for future biotechnology products. These collaborative efforts could expand technical capability and enhance efficiency in developing risk-analysis methods and also enhance efficiency and effectiveness in evaluating products intended for U.S. import. Harmonized guidelines also support efficiencies for U.S. developers intending to export their products. Finally, the agencies may wish to interact with third parties to advance research and development of new testing techniques, risk models, and other techniques to support risk analyses for future products.

In developing the recommendations of its report, the committee assessed the opportunities for enhancing the capabilities of the U.S. biotechnology regulatory system through interactions with this broad community of interested and affected parties. These interactions are especially important in areas of rapid technology change, such as biotechnology, where the regulatory agencies must maintain adequate capability to allow appropriate assessments of new technologies that go beyond existing biotechnology products and for which there may not yet be well-established approaches to risk analyses. These interactions are especially important in areas where there may be substantial public discussion regarding the risk–benefit tradeoffs of a technology, ethical considerations, and competing international activities that influence U.S. policy and trade.

The committee did not consider it to be part of its task to comment on the structure of the U.S.

regulatory system and whether it was optimally situated to provide appropriate oversight of future biotechnology products. Rather, it focused on the current system as described in the update to the Coordinated Framework (EOP, 2017) and tried to articulate the extent to which future products of biotechnology would generate new types of risks and to identify the opportunities for enhancing the capabilities and capacity of the biotechnology regulatory system to handle types of products that the committee saw on the horizon.

REFERENCES

Cohen, S.N., A.C.Y. Chang, H. Boyer, and R.B. Helling. 1973. Construction of biologically functional bacterial plasmids in vitro. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 70:3240–3244.

EOP (Executive Office of the President). 2015. Memorandum for Heads of Food and Drug Administration, Environmental Protection Agency and Department of Agriculture. July 2. Available at https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/microsites/ostp/modernizing_the_reg_system_for_biotech_products_memo_final.pdf. Accessed January 31, 2017.

EOP. 2016. National Strategy for Modernizing the Regulatory System for Biotechnology Products. Available at https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/microsites/ostp/biotech_national_strategy_final.pdf. Accessed January 31, 2017.

EOP. 2017. Modernizing the Regulatory System for Biotechnology Products: An Update to the Coordinated Framework for the Regulation of Biotechnology. Available at https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/microsites/ostp/2017_coordinated_framework_update.pdf. Accessed January 30, 2017.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2016a. Gene Drives on the Horizon: Advancing Science, Navigating Uncertainty, and Aligning Research with Public Values. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2016b. Genetically Engineered Crops: Experiences and Prospects. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NRC (National Research Council). 2015. Industrialization of Biology: A Roadmap to Accelerate the Advanced Manufacturing of Chemicals. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

OSTP (Office of Science and Technology Policy). 1986. Coordinated Framework for Regulation of Biotechnology. Executive Office of the President. Federal Register 51:23302. Available at https://www.aphis.usda.gov/brs/fedregister/coordinated_framework.pdf. Accessed September 24, 2016.