Chapter 5 focuses on how elements of the existing health and public health frameworks can be applied to strengthen and support CVE programs. By incorporating lessons learned in analogous programming that combat other types of violence, health and public health practitioners could promote community resilience, encourage community engagement, and help to gather evidence about the risk and protective factors that underpin radicalization toward violence. The evaluation of these programs, an essential component of public health models, is also discussed, as are the set of practical and ethical challenges health professionals face when working in CVE roles.

THE PUBLIC HEALTH APPROACH TO ADDRESSING THREATS

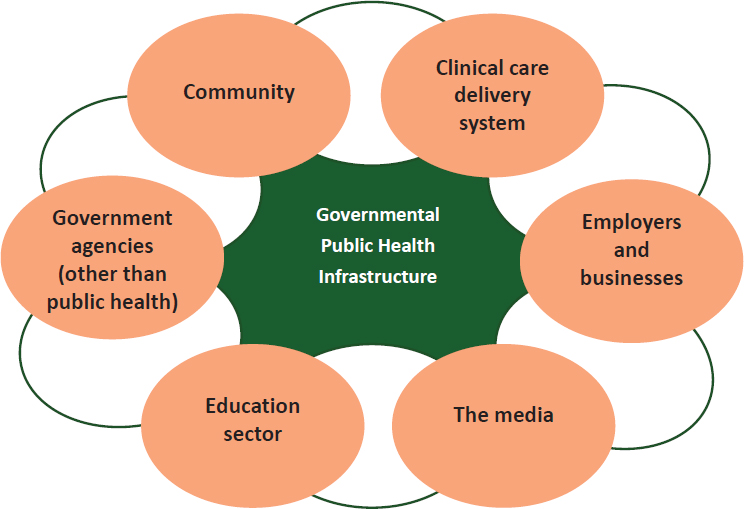

Eisenman noted that more than 2,500 federal, state, and local agencies constitute the backbone of the U.S. public health system and bear the legal responsibility for assuring the delivery of essential public health functions. The public health profession incorporates both health care delivery systems and academic public health sciences; however, he pointed out that there are multiple other sectors that contribute to the public health system and to population health (see Figure 5-1).

Steps in Implementing a Public Health Approach to Violence Prevention

In their respective presentations, Georges Benjamin and Leesa Lin detailed CDC’s four key steps for implementing a public health approach to address health threats, including violence prevention1:

- Define the problem using reliable data: “who,” “what,” “when,” and “how.”

- Identify risk and protective factors using scientific research methods: what factors protect people or put them at risk?

- Develop and test prevention strategies using evaluation.

- Assure widespread adoption using additional evaluation, training, and/or technical assistance.

___________________

1 Source: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention. For more information on the Public Health approach see http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/overview/publichealthapproach.html (accessed November 8, 2016).

SOURCE: Eisenman presentation, September 8, 2016.

Step 1: Define the Problem Using Reliable Data: “Who,” “What,” “When,” and “How”

Benjamin explained that the first step is to use data to define and monitor all facets of the problem at hand. This includes understanding who is at risk, what they are at risk of, when the problem is more likely to occur, and where it is likely to occur. Gaining clarity about the problem and how to address it also provides the necessary groundwork for putting measures into place for monitoring interventions, he explained.

Step 2: Identify Risk and Protective Factors Using Scientific Research Methods

The second step, according to Benjamin, is to identify the risk factors and protective factors at the individual, community, and broad societal levels that contribute to making certain communities more susceptible than others to experience a health threat. Such factors include issues such as the

availability of firearms, religiosity, and level of wealth. He explained that the public health approach focuses heavily on exploring how these factors coalesce around particular problems.

Step 3: Develop and Test Prevention Strategies: Four-Tiered Model of Public Health Prevention

Benjamin stated that the third step is to apply knowledge gained about the problem, as well as its risk and protective factors, toward developing hypotheses about potentially effective interventions and putting programs into place. He noted that actually measuring and evaluating the efficacy of public health programs tends to be erratic. In many cases, a program is implemented and associated with a desirable health outcome; the program is then championed as effective without the benefit of a formal evaluation to determine whether or not the outcome was actually caused by chance. This highlights the importance of incorporating evaluation measures to assess success in preventing or mitigating health threats, he argued. He explained, however, that regardless of whether the program’s success has been empirically validated, if it is ostensibly successful and contributing to positive momentum, then the next goal is to work toward prevention of the problem. Eisenman contended that it would be fair to construe all public health activities as preventative. Furthermore, he suggested that it would be more apt to frame the entire CVE enterprise as the prevention of violent extremism, not countering it.

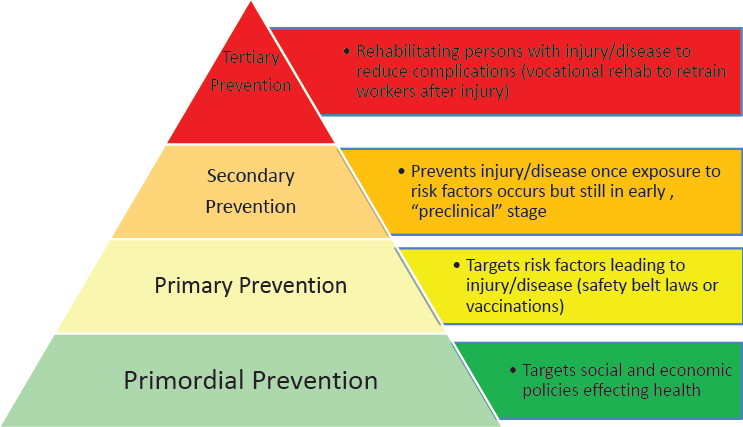

To explain how the public health sector implements the task of prevention, both Eisenman and Benjamin explored the multitiered public health model, which encompasses multiple levels of prevention (see Figure 5-2).

Primordial prevention strategies are situated furthest upstream, noted Benjamin. Eisenman explained that the primordial prevention level is not always included in the public health model (some of which have only three tiers of prevention), but suggested that it warrants more attention. For example, by blocking American tobacco companies from introducing tobacco products into developing countries, public health advocates were successfully able to prevent the introduction of new risk factors for disease into those countries. He explained that in subsequent years, primordial prevention has come to be associated with changes in the country or changes in macrolevel social and political policies to prevent disease. Lin described primordial prevention as addressing fundamental health determinants at the system level.

Benjamin explained that the goal of the next tier, primary prevention, is to avert a health threat by addressing its root causes before they result in a disease or injury. Primary prevention efforts are upstream strategies aimed at reducing exposures to hazards, altering risky behaviors, and

SOURCE: Eisenman presentation, September 8, 2016.

increasing resistance to disease or injury should exposure occur. He cited several examples of primary prevention strategies, including preventing exposure to secondhand smoke, building sidewalks to encourage and enable walking to promote cardiovascular health, promoting the use of seat belts or bicycle helmets, and vaccinating against pneumococcal pneumonia to protect individuals and strengthen herd immunity. He suggested that another primary prevention strategy with particular relevance to the CVE space—and violence prevention more broadly—is geared toward preventing early childhood trauma, which he described as a predictor of impulse control problems and future violent tendencies.

The goal of secondary prevention is to reduce the effect of a disease or an injury that has already occurred, said Benjamin. This process may involve strategies for detecting and treating a disease or injury as soon as possible to halt or slow its progression, encouraging personal strategies to prevent reinjury or recurrence, and implementing programs to return people to their original health and ability to function. Secondary strategies include, for example, tobacco cessation support for a person with coronary artery disease, mammograms and colonoscopies for detecting and treating early-stage malignancies, and treatment with antibiotics for pneumococcal pneumonia infection. In the context of violence prevention, he suggested that secondary prevention strategies might involve engaging with youth who are gang members without a history of violence. Intervening at that

point may reduce their elevated risk of violent behavior as they enter adulthood and possibly become more involved with gang activities.

Benjamin described tertiary prevention strategies as concentrated on reducing the effect of an ongoing illness or injury that has lasting effects, as well as preventing its recurrence. He explained that tertiary prevention is accomplished by helping a person to manage a chronic disease and disability, such as by using medications to control hypertension in a stroke patient or providing rehabilitative therapy to a person who has had a myocardial infarction. Eisenman contributed the example of vocational rehabilitation to help retrain workers after they recover from an injury. According to Benjamin, the goal of tertiary prevention is to improve the person’s ability to function, quality of life, and life expectancy. Intervening with an individual who has been a victim of violence to prevent retaliation is another form of tertiary prevention, because engaging with the victim can help to break the cycle of violence that can escalate from relatively minor injury to retaliatory serious injury or death, Benjamin noted.

Step 4: Assure Widespread Adoption Using Additional Evaluation, Training and/or Technical Assistance

After effective strategies have been identified, the fourth step is to assure their widespread adoption by disseminating and implementing them broadly. Benjamin highlighted the four Es of prevention: education, environment, enforcement, and evaluation. He suggested that education efforts should cast a wide net and cover individuals at risk, policy makers, and the public at large. Environmental efforts should aim to make the environment as safe as possible for individuals (e.g., providing home safety inspections for older people who have fallen and broken their hips). Benjamin emphasized that solutions must “go viral” with improved efforts to disseminate best practices that can be customized for specific environments.

Applying the Tiered Model of Public Health Prevention to CVE

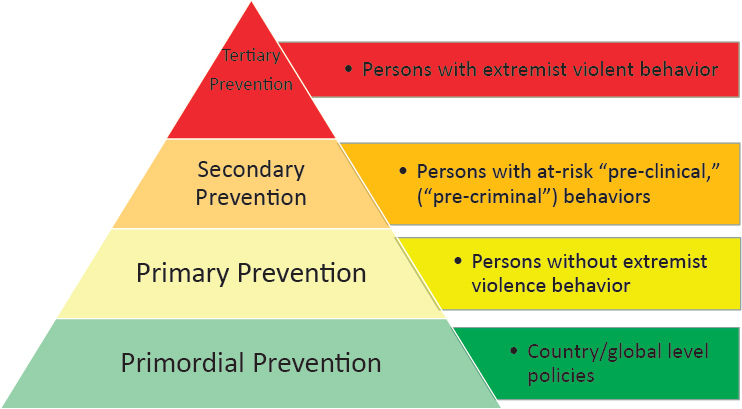

Benjamin emphasized that the relationships between the four categories of prevention activities are complex, context dependent, and not always easily delineated. However, he suggested that understanding where a given program fits into the spectrum of prevention strategies is an important step in building a system for CVE. Both Benjamin and Eisenman explored how public health’s four-tiered model of prevention can help to map out strategies for preventing extremist violence. Eisenman noted that most activities within existing CVE programs would fall under some level of the public health prevention model (see Figure 5-3).

Universal prevention strategies, according to Eisenman, frame vio-

SOURCE: Eisenman presentation, September 8, 2016.

lent extremism as a problem for all communities, and such strategies are predicated on the assumption that all communities have opportunities for violence prevention. In the CVE space, he noted, primary prevention is concerned with targeting the majority of the population who have not engaged in problematic behaviors associated with violent extremism. Eisenman explained that such activities can include community programs and coun-ternarrative media campaigns to reduce risk factors and strengthen protective factors for individuals, families, and communities. These activities may either be CVE relevant or CVE specific, he noted. Benjamin suggested that programs in the primary prevention category could be broadly construed as community-level strategies that mitigate modifiable risks, such as limiting the availability of extremist media and reducing social isolation and exclusion. He contended that this can be done sensitively without stigmatizing or profiling individuals but by using data-driven methods to identify individuals at risk, a process that will require ongoing scientific research.

Eisenman explained that secondary prevention targets a subset of the population who are considered to be at risk for violent behaviors. He likened secondary strategies for detecting the behavioral changes in individuals that precede violent acts to strategies for detecting and addressing the

preclinical changes that occur before a disease manifests.2,3 Examples of CVE-specific and CVE-relevant program activities include targeted violence threat assessment programs, “off-ramps,” and interventions for people at risk before they commit violence. Benjamin similarly described secondary prevention strategies as directed at individuals who have some characteristics that put them at an elevated risk for violent extremism (e.g., exposure to extremist ideologies or proximity to a radical social network). On the contrary, Lin pointed out that exposure to extremist ideologies cannot be considered as a precursor of the “disease” and thus screening at the population level to detect and treat a disease at an early stage to prevent it from progressing (aka secondary prevention) cannot be done for CVE. She argued that given there is not sufficient evidence of the risk factors for violent extremism—science has yet to determine what puts individuals at a higher risk of committing an act of violence—secondary intervention for violent extremism is not feasible.

Tertiary prevention strategies, according to Benjamin, are directed at individuals who have already adopted extremist ideologies or are in contact with violent extremists, but are not engaged in planning or carrying out acts of violence, in order to divert them away from the path to violence. Eisenman explained that tertiary prevention activities, such as deradicalization programs, can help to manage and rehabilitate people who have already manifested criminal intent and violent extremist behaviors; these activities are generally housed in CVE-specific programs.

Eisenman suggested that primordial prevention for CVE could address the broad range of political, social, economic, and historical forces or grievances that can create and reinforce the conditions for violent extremism (e.g., Western foreign policy, wars in the Middle East, and the global distribution of wealth). He noted that while primordial prevention strategies are not generally on the forefront of the public health approach, there are advocates in the field who are active in attempting to address the social determinants of risk by promoting policies that improve human rights and reduce inequalities on both national and global levels. He noted that many such activities may not be CVE specific, but are CVE relevant.4 Lin added that primordial prevention addresses broad health determinants at the

___________________

2 He noted such behaviors are often referred to as precriminal, but clarified that it is not a public health term and its use may be counterproductive and perpetuate stigmas.

3 For example, the Los Angeles Targeted Violence Threat Assessment Program is a secondary prevention program for people who have been identified with precursor behaviors but who have not yet committed a violent extremist act.

4 More information and definitions of these terms can be found in Does CVE Work?: Lessons Learned from the Global Effort to Counter Violent Extremism report, which can be found at http://www.globalcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Does-CVE-Work_2015.pdf (accessed January 17, 2017).

SOURCE: Lin presentation, September 8, 2016.

system level to minimize future hazards to health and inhibit the establishment factors.

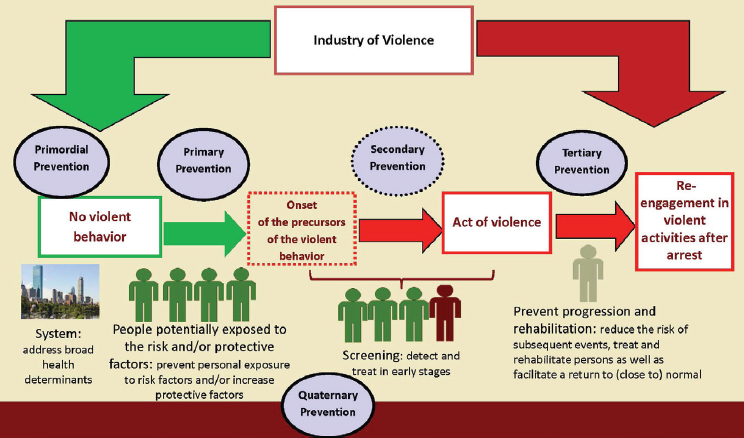

Lin suggested adopting a fifth tier—quaternary prevention—that wouldinclude actions taken to oversee the civil liberty and ethical issues intrinsic in all levels of prevention, in order to ensure that people are not overtreated for behaviors that are not a risk (see Figure 5-4).

Woodie Kessel, senior scholar at the Koop Institute, cautioned against assuming there is one most efficient strategy for prevention, arguing that all levels of prevention will require promotion, attention, investment, and consideration.

Applying CDC’s “10 Essential Functions of Public Health” to CVE

Eisenman introduced CDC’s 10 Essential Functions of Public Health in order to provide guidance about how the public health approach, system, and workforce can contribute to preventing extremist violence. He explained that these 10 essential functions are widely accepted as forming the foundation for all public health activities, and presented a figure (see Table 5-1) detailing how each of the 10 essential functions can be applied to prevent violent extremism (Weine et al., 2016).

Eisenman explained that the first two functions fall under the auspices of public health assessments; in the CVE realm, this involves applying public health data to help understand CVE needs. He reiterated Benjamin’s

TABLE 5-1 CDC 10 Essential Public Health Functions and CVE

| Essential Public Health Function | Activity Applied to CVE |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SOURCES: Eisenman presentation, September 8, 2016; Weine et al., 2016.

contention that data is the foundation of the public health enterprise, pointing to the usefulness of using relevant information from population-level public health surveillance surveys to inform CVE activities, particularly as research continues to improve understanding of the relevant risk and protective factors for violent extremism. For example, he suggested that many of the protective factors that are posited to mitigate against violent extremism—such as social cohesion and access to health care—could be the same factors that allow communities to withstand stresses and sustain healthy behaviors in the face of adversity. He noted that perceived discrimination and trust in government are often measured in public health surveillance surveys. Eisenman suggested that public health could also contribute by codifying definitions of violent extremism that lend themselves to prevention programs with a clear connection to health and well-being.

Functions 3, 4, and 5 in Table 5-1 pertain to the core public health function of developing policies and plans for health, according to Eisenman. Activities include informing and empowering communities, mobilizing partnerships, and developing policies and plans. He proposed that CVE could be addressed within the wider context of violence prevention generally, with the public health sector serving as convener and helping to assemble community sectors and agencies around CVE, as well as providing technical assistance on program planning and grant funding. Furthermore, he suggested that public health could contribute to policy making and program development, thereby helping to shift CVE away from its dependence on law enforcement and closer to the mental health education, youth development, and other human services sectors.

Eisenman explained that functions 6 through 10 represent the public health core functions of ensuring the populations’ universal access to a culturally competent health system, for both general health and prevention. These functions include enforcing health and safety laws and regulations, linking people to needed health services, assuring a competent health workforce exists, researching and evaluating programs, and advocating for CVE-related laws and policies that guard against civil liberties violations and stigmatization.

Protective Factors and Interventions: Scope and Subjectivity

Wynia asked whether the types of interventions under consideration play an important role. If someone is inaccurately predicted to be on the path to violent behavior, he questioned whether it matters which interventions are available in terms of making that judgment. Steele replied that it depends on the scope of the program and the nature of the intervention. If the scope of the program is violence prevention writ large, for example, and the type of intervention is social services, then those services may help

an individual to better adjust and could potentially prevent that individual from going on to commit violent extremism. Even if the individual goes on to join a gang, she remarked, it is still positive value for that individual if violent behavior is averted. She contended that when it is a positive intervention in terms of social services, the risk of a false positive may be mitigated, and suggested that the key is to implement an iterative process to determine the right scope of programs, find positive opportunities for intervention, and improve the specificity of intervention tools.

Interventions that practitioners may view as positive and free of risk may not be perceived or experienced as such by the person who receives it, Wynia pointed out. For instance, a practitioner might think that there is no harm in engaging with a person who seems to be on the path to violence and referring the person to counseling. However, if the consequences of that counseling referral are loss of employment and social standing in the community, then that was neither a risk-free nor an inevitably beneficial intervention. Wynia explained that as a practitioner, he tends to categorize public health interventions as binary: either positive or negative. Positive interventions are those that promote health; negative interventions are ones that prevent the spread of disease. He suggested that there may be a gray area in between where, depending on the person’s perspective, an intervention may be positive or negative. He noted that this type of subjectivity seems particularly common in the CVE arena. Steele suggested that integrating health approaches into CVE efforts could bring valuable lessons about how to mitigate that type of stigma, as well as offer guidance about tailoring interventions to reduce the potential for stigma.

In discussing protective factors and the scope of interventions, Wynia noted that much discussion has centered on moving the bell curve by looking at populations and the social determinants of peoples’ choices and behaviors. He asked about the appropriate balance between a focus on shifting the bell curve, and a parallel focus on identifying and intervening with people on the path to violence. Steele remarked that CVE is a challenge faced by the whole of society, which thus requires “whole of society” approaches. She suggested that the partners involved in improving and amplifying protective factors may be different than the partners involved in the more narrowly focused interventions. She reported that discussions with partners in the education sector have focused on what type of work can be done to improve protective factors, to deliver positive messages, and to foster a sense of inclusion in schools. She suggested that these are the types of interventions that are more likely to have broad public support, because they are ones in which a range of partners can add value. As a caveat, she noted that those types of interventions should not be implemented to the exclusion of other types of efforts that may have more difficulty in garnering public support.

NOTE: NGO = nongovernment organization.

SOURCE: Eisenman presentation, September 8, 2016.

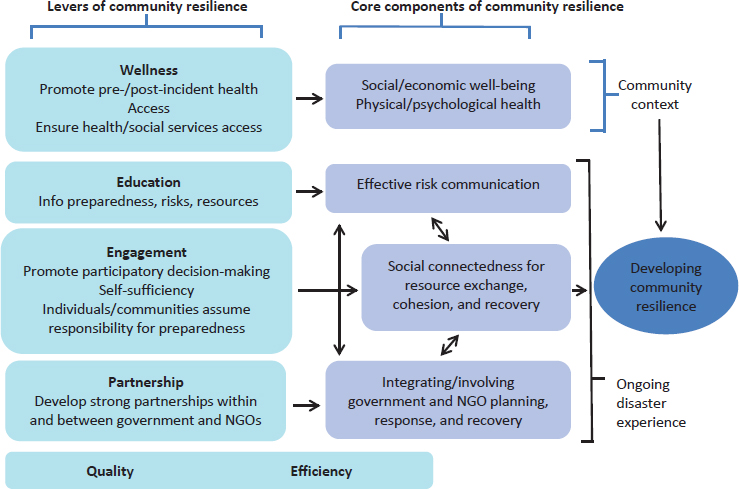

Public Health Approach to Building Community Resilience

Eisenman called for the public health sector to help promote the concept of community resilience in the context of violent extremism.5 He defined community resilience from the perspective of public health as “the capacity of the community as a whole to prepare for, respond to, and recover from adverse events and unanticipated crises that threaten the health of all,” and suggested that it could be reframed in a way that is pinned toward achieving CVE-specific outcomes. He introduced a public health theory about how to build community resilience after a disaster, and suggested that a similar theory could be effective in the CVE arena (see Figure 5-5).

According to Eisenman, the theory posits that factors contributing to community resilience include wellness, access, education, engagement, self-sufficiency, partnership, quality, and efficiency. These factors serve as levers to bolster the core components of community resilience within society.

___________________

5 He noted that several national policies now incorporate community resilience: Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA’s) National Disaster Recovery Framework; National Health Security Strategy of the United States (2009); Public Health Preparedness Capabilities; and FEMA ESF #14: Long-term community recovery.

Hick observed, from a practical standpoint, that there is ample room for improvement. He offered the example of overwhelming meningococce-mic disease: by the time the disease is eventually recognized and diagnosed in the emergency department, the patient will have a high risk of death even with the best treatment possible. But in the early stages, there is nothing a physician can do to recognize that it is different from any other viral illness, so the only strategy is to vaccinate. Applying the disease analogy to CVE, he suggested there are circumstances in which primordial and primary strategies must provide thrust and “inoculate” the community with culturally competent and specific values. Hick said,

I can tell my kids hate is not a Christian value, and you can tell your kids, if you’re Muslim, that hate is not a Muslim value. How do we continue to build that into the system? Movement of small shifts in the population may make a difference.

Wynia asked whether there may be any potential drawbacks or disadvantages linked to efforts to promote resilience. He went on to say that the only place he had encountered negative feedback about such efforts was in clinical care settings; the perception among the doctors and nurses was that it was an effort to prolong their ability to work. He questioned whether securitizing or medicalizing these types of community-based interventions would run the risk of a similar response from the public that resilience is being used as a tactic to control political beliefs under the banner of a healthy community. Steele emphasized that resilience is not intended to be about belief system control, but about channeling resilience to nonviolent action. She suggested that there are ways to reduce the risk of violence while still giving a voice to those grievances.

Working on Violence as a Public Health Issue: Reflections from a Practitioner in the Field

Wen introduced the concept “hurt people hurt people” as framing her work in addressing violence from a public health perspective. For example, she reported that among the people currently incarcerated in Baltimore City, 40 percent have mental illness and 80 percent use illegal substances; nationwide, only 11 percent of addicts can get the help they need. She remarked:

We continue to treat addiction as a moral failing when in fact it is a disease. . . . Whose fault is it when individuals with addiction end up leaving jail without having their addiction treated in the first place, and then end up in the cycle once more because they do not have employment or because they do not have housing? Whose responsibility is that to break that cycle? We see that as our responsibility in public health to start that conversation,

but with the help of everybody else. . . . We must dig deeper and not just see that person in front of us as the perpetrator of violence.

Wen related a formative experience that informed her understanding of violence as a public health issue. While she was working as an emergency room physician, a teenage patient was admitted with gunshot wounds to the abdomen and chest; health care providers in the room recognized him as having been admitted multiple times with various violence-related injuries over the course of the previous year: a gunshot wound to the arm, a hand fracture from punching someone, and a head injury received in a fight. She characterized him as a powerful exemplar of being caught in a cycle of violence, a cycle in which the perpetrators of violence are often the victim of violence as well. Wen cautioned against looking at what individuals are doing in a single instance without recognizing the policies and circumstances that led to the behavior, such as discriminatory policies in policing, mass incarceration, incarceration of people who have addictions, and treating addiction as a crime and not as a disease.

Wen offered three messages based on her experience working on violence through a public health lens. First, she urged the group to dig deeper and to look beyond individuals as the perpetrators of violence, and to recognize that they are the victims of deep trauma. She explained that in Baltimore City, an ambitious program is in place to train every front-line worker in the city (including social workers, doctors, police officers, and teachers) on trauma-informed care in order to strengthen their abilities to understand, respond to, and treat the impacts of trauma. More than 1,200 people have been trained so far, and the next step is to train every individual in the city who will somehow be in touch with a child to recognize and understand the effects of trauma.

Her second message highlighted the need to invest earlier. In Baltimore, the City Health Department houses the Office of Youth Violence Prevention, predicated on the idea that investing in early childhood is the best way to prevent violence. She described a program in Baltimore City called “Vision for Baltimore,” which was founded in 2016 to achieve one basic goal: to provide glasses to every child in the city who needs them by screening all students in Baltimore City public schools between 2016 and 2019.6 Less than 20 percent of children who are screened as needing glasses actually have them, leaving up to 10,000 children in the city with uncorrected vision. She emphasized that the simple investment in a child’s glasses can potentially be a violence prevention strategy: it may prevent a child from being labeled disruptive and losing traction in school to the point that

___________________

6 Program information available at http://health.baltimorecity.gov/VisionForBaltimore (accessed November 8, 2016).

he or she engages in a cycle that ultimately leads to violence. She stated that investing in children as early as possible is crucial. A program called Baltimore for Healthy Babies, founded in 2009, has thus far resulted in a 28 percent reduction in infant mortality and a 36 percent reduction in teen birth rates. Nurses, social workers, and case workers visiting homes to teach about safe sleep practices and other child rearing practices not only improves a child’s educational outcomes, but also reduces the likelihood of the child being involved in violent activities later on in life.7

Wen listed her third point as being at the core of public health: looking at the cost of doing nothing. In a sense, she noted, the face of public health is one that does not exist because it saves lives without recognition—from the prevention of food-borne illnesses, to interventions that help mediate conflicts or improve a child’s educational outcomes, to intervening in the pathway to violence. She urged everyone involved in public health to talk about the cost of inaction, particularly in high-risk communities.

She explained that the Baltimore Safe Streets program,8 based on the national Cure Violence program, continues to face funding problems on a yearly basis, despite former gang members and criminals making efforts to stop conflict (mediating nearly 700 conflicts in the previous year) and to give back to their communities. She cited a forthcoming study from Johns Hopkins University that found the Baltimore Safe Streets program to be more effective than any other public health intervention in the previous 10 years, at a cost of just $1.7 million per year, which is dwarfed by the millions of dollars it saves in Medicaid, disability, unemployment, and incarceration. The program is so effective because it is implemented by individuals who have literally walked in the shoes of the people they are helping. Similarly, needle exchange programs have been in place in the city for more than 20 years, reducing the percentage of individuals living with HIV from IV drug use from 64 percent in 2000 to 8 percent in 2014. She posited that its success is driven by the fact that people working on the program are people who are themselves in recovery or living with HIV or hepatitis.

Cure Violence Program: Promoting Local Credible Messengers

Jalon Arthur, director of Innovation and Development for the Cure Violence program, School of Public Health, University of Illinois at Chicago, explained that the national Cure Violence program9 is an evidence-informed

___________________

7 Program information available at http://healthybabiesbaltimore.com (accessed November 8, 2016).

8 Program information available at http://health.baltimorecity.gov/safestreets (accessed November 8, 2016).

9 Program information available at http://cureviolence.org (accessed November 8, 2016).

health approach that views and treats violence in all its forms as an infectious health issue, because violence is the leading cause of death in the communities and populations the program serves. He pointed out that like other infectious diseases, violence is not distributed equally: there are epicenters in communities, places like Chicago, Honduras, and Syria. He remarked that violence spreads through exposure, with violence begetting violence: whether it is acts of violence in the home, in the street, in war, or acts of violent extremism.

Many people in communities do not want to see their loved ones or their peers become radicalized, but at the same time, they do not want to see their loved ones or their peers arrested or imprisoned, explained Arthur. Thus, there may be a host of missed opportunities to effectively interrupt the process of radicalization because many people will simply not engage with law enforcement for fear of imprisonment of themselves, loved ones, or peers. In many cases, there is information that is under the radar of the CVE space but known by someone at the community level who does not know how to respond to it.

Credible messengers at the community level can take advantage of their own powerful networks to facilitate a system for efficient detection and response, Arthur emphasized. Empowering community members to serve as a bridge providing critical services for vulnerable people is a critical piece of what Cure Violence and other health approaches can offer, he said. In a community that has a network of credible messengers who are promoting the process of radicalization, it is crucial to empower another smaller credible group within that community to push in the opposite direction away from radicalization.

Training individuals and community groups to recognize people at risk is critical, he explained. A common thread among those who become radicalized is that somebody close to them notices that something is “off” or wrong. By educating a community through the Cure Violence program, or other health-based violence prevention approaches, and by using a pool of credible messengers, a community is able to detect and interrupt this radicalization process. This can provide a trusted and respected alternative to contacting law enforcement. This has been effective in Cure Violence programs within communities where daily shootings used to take place, but have now gone 1–2 years without a single shooting or a homicide. This is an average of a 40–70 percent decrease in violence, according to five independent evaluations, Arthur explained.

Another component of the Cure Violence program is the convening of trusted stakeholders in community forums, town hall meetings, and conferences to strategize and put forth solutions on how to address an epidemic of violence. Arthur explained that these venues offer opportunities to air grievances, share and challenge ideas, exchange perspectives, and

present peaceful alternatives. Trusted community insiders can meet without judgment (in the absence of law enforcement), serving as a powerful vehicle for encouraging positive recruitment and allowing people who feel alienated to become part of a bigger group dynamic. He suggested that in the CVE space, given the right trusted messengers, similar approaches could provide platforms for deradicalization.

In regard to CVE, Arthur observed some recurring narratives and concerns that warrant consideration. One is that with a low incidence of violent extremism, many communities are reluctant to buy into CVE efforts at the expense of other issues pervading their communities. Another common concern is that the government has a vested interest in vulnerable communities only to the extent to which the threats—either real or imagined—pose to the larger society. The takeaway for some people at the community level is that whole communities are permitted to suffer through tragedies and more traditional forms of violence, as long as the problems are contained within that community and do not escalate to what would be considered violent extremism.

He urged that these sentiments should be taken into consideration and warned that programs perceived to be government led can often be counterproductive and lack community-level buy-in, without which the program will not work. He emphasized that even the most well-intentioned and best thought-out efforts and interventions can fail if they are not supported by local community champions who can leverage their own credibility and encourage others to understand that it is a health issue worth engaging.

PUBLIC HEALTH MODELS FOR EVALUATING CVE PROGRAMS

Evaluating Community-Led Interventions

Ramchand remarked that there is a tradition in public health to begin working toward prevention immediately when a crisis emerges, even before the mechanisms that underlie the outcomes are fully understood.10 Ramchand explained that this tradition holds in the CVE domain: while experts continue to do the important work of investigating the factors that lead certain individuals to violent extremism, community-led organizations and programs are already on the front line implementing interventions to prevent it. However, he emphasized that because little is known about the actual efficacy of the CVE interventions, it is now critically important to scientifically assess and evaluate those programs. He contended that given the resource-constrained environments for funders, assessment and evaluation

___________________

10 For example, the Gay Men’s Health Crisis was formed in New York City before HIV was identified.

can be used to guide decisions about which programs should be sustained with funding. Evaluations of how different interventions and activities are working can also inform the science of understanding the potential trajectories of violent extremism, he suggested. A further benefit he highlighted is that instilling a culture of evaluation within those community-led organizations allows them to take ownership of identifying and initiating their own program changes and improvements as needed.

Developing a Tool Kit to Aid Community-Based Organizations: Getting to Outcomes

RAND was commissioned by DHS in 2011 to develop a tool kit to aid community-based programs in evaluating their own CVE programs, explained Ramchand. As an initial step, the researchers turned to an existing resource called Getting to Outcomes, an evidence-based approach to evaluation that has been used to aid many community-based organizations in the public health sphere in assessing their own programs. RAND adapted the model to create a similar tool kit for community-based programs seeking to prevent suicide. He noted that there are parallels between suicide prevention programs and CVE programs. For example, the outcomes the programs are seeking to prevent are significant but also very rare, low-base-rate events with high levels of false positives. He observed that this can deter organizations from evaluating their programs, which hinders their ability to adjust and improve. To create a model for evidence-based program evaluation that would be applicable to a diversity of program types, RAND reviewed a corpus of relevant research, drawing on 166 peer-reviewed evaluation studies of suicide prevention programs.

Ramchand explained that the next step was to apply this work toward building a five-step tool kit for CVE program evaluation:

- Step 1: Identify your program’s components, and build a logic model.

- Step 2: Design an evaluation.

- Step 3: Select evaluation measures.

- Step 4: Analyze evaluation data.

- Step 5: Use evaluation data to improve the program.

He focused on the formative research that was carried out to understand the activities and outcomes common to U.S.-based CVE programs in order to develop the CVE-focused content for Steps 1 and 3. The first step involves programs identifying core competencies and organizing those components in a logic model; he noted that effective evaluations require all of the components of a program to be well specified.

Ramchand detailed how after programs create their own logic model, they are linked to appropriate evaluation measures and available validated metrics that program managers can use to assess and measure the programs’ outcomes (Step 3 in RAND’s five-step tool kit).

To identify the activities, outcomes, and metrics relevant to the CVE space, Ramchand reported that the researchers performed a literature review of prior assessments of CVE programs’ effects and limitations. A systematic search of 200 CVE assessment publications produced only seven studies that assessed CVE outcomes and demonstrated the potential effectiveness of those programs. However, he noted that the scientific rigor of those studies was extremely limited compared to other academic disciplines (e.g., lack of control group, lack of empirically validated metrics). A survey was also carried out to identify activities and outcomes common to U.S.based CVE programs. He reported that researchers were able to carry out successful interviews with 28 of 94 CVE programs contacted (33 percent response rate; program focus: 46 percent Islamic extremism, 54 percent other forms of extremism).

Reasons for Lack of CVE Program Evaluations

To tailor the tool kit for CVE, Ramchand explained, program administrators were asked specifically about evaluation activities and why such activities were not pursued. He reported that the most common reasons cited for the lack of evaluations were lack of resources and administrator uncertainty about data. Regarding the former, Ramchand explained that administrators responded that they did not have enough resources to follow up with participants or conduct surveys, that they had few (if any) staff who are familiar with evaluation, and that they prefer to devote scarce resources to program administration.

Ramchand noted that administrators’ uncertainty and confusion about data revealed multiple concerns: they were worried about appearing intrusive in asking for structured feedback from people who participated in the program; they perceived available data options as uninformative (especially with respect to the Likert scale); and they felt uncertain about the most appropriate metrics for their programs. Furthermore, administrators reported struggling with how to measure and demonstrate the counterfactual—the number of extremist acts the program had prevented. Ramchand suggested that employing proximal outcomes can resolve this issue, allowing administrators to focus on their programs’ near-term objectives.

Shaping the CVE Tool Kit

Based on the information gleaned from the literature review and survey, Ramchand noted that the researchers returned to the logic model framework to create a tool kit that was designed to effectively address the barriers identified. He explained that to identify relevant outcomes, programs must clearly specify the audience their activities are targeting. That is, different activities may be geared toward targeting the subset of individuals at risk of committing violent extremism, versus those targeting the families, communities, and institutions that influence or interact with individuals at risk of committing violent extremism.

Once a target audience is specified, the tool kit helps guide programs into considering their likely program objectives. He observed that programs targeting individuals are generally focused on the following outcomes:

- Countering violent extremist opinions and ideology

- Improving psychological well-being and addressing moral concerns

- Enhancing positive social networks

- Reducing political grievances

- Improving social and economic integration

In contrast, he observed that programs targeting the communities surrounding individuals at risk of extremism are generally focused on the following objectives:

- Helping community members understand and identify violent extremism and its risk factors.

- Building community capacity to identify and engage with those at risk.

- Building the capacity of positive, influential members to credibly counter violent extremist ideologies.

- Creating environments that accept minority groups.

- Promoting policies that address political grievances.

- Strengthening capacity to curtail violent extremism.

He explained that identifying their objectives helps guide programs as they customize their logic model. They are then consequently provided with the appropriate available metrics that they can use to assess whether the program is stimulating the intended types of change. Furthermore, he noted that the tool kit provides comprehensive guidance for all five steps of the tool kit, including how to design an evaluation, analyze evaluation data, and use evaluation data to improve programs. The aim, according to Ramchand, is to create an ethos of continuous and ongoing evaluation

within programs. Feedback from administrators who piloted the tool kit suggested that cultivating this ethos is crucial, because community organizations will not use the tool kit without active efforts to educate them about the value of evaluation.

Applying a Public Health Approach to the Evaluation of CVE

Lin traced the development of a pilot evaluation program for preventing violent extremism in the greater Boston area. She noted that the project’s timeline allowed for independent external evaluators to become involved in a formative evaluation capacity before the pilot was implemented, which informed the program’s design.

Lin reported that more than 50 stakeholders from 45 organizations took part in the initial interview process.11 Two interviewers visited each interviewee’s workplace, which were primarily community-based organizations, to gain contextual information about the communities they serve, the programs in place, and the interpersonal relationships at play. Ultimately, the researchers conducted more than 24 hours of interviews and collected approximately 2,000 statements. She emphasized how important it is for evaluators to ensure transparency and timely communication in order to foster trust among interviewees.

The next step, according to Lin, was to identify challenges faced in the design and implementation of violent extremism prevention programs based on the stakeholders’ feedback and a thorough review of available literature. The principal challenge they identified concerned the name and scope of the programs; she explained that the controversial history associated with the term CVE was discouraging stakeholders’ participation. She estimated that 98 percent of interviewees stated bluntly that they would not take part in a program with the CVE label because it would risk undermining the trust and relationships they had worked to build with the communities they serve. Furthermore, she noted a lack of support for any violence prevention program that is too narrow in scope, as in focusing only on a particular subset of the population.

The second challenge Lin’s team identified is the lack of a clear, agreed-upon definition for violent extremism and of clear outcomes across CVE programming, according to Lin. To illustrate, she cited the National Strategy on Empowering Local Partners to Prevent Violent Extremism (The White House, 2011), which defines violent extremists as “individuals who

___________________

11 Types of agencies (n = 45): academia (20 percent) and health care and mental/behavioral health (16 percent), which she noted are not mutually exclusive; community-based organizations (40 percent); and government agencies (including law enforcement and schools) (24 percent).

support or commit violent extremism to further political goals.” She reported that in trying to use that definition as guidance for defining the outcomes of the pilot evaluation program, the researchers realized that the definition fails to specify what type(s) of ideologies are being referred to, what type of violence is being targeted (for example, whether it should include bullying or verbal discrimination), and what is meant by “support” (for instance, the types of social media interactions that constitute support).

Limited evidence regarding the risk factors for violent extremism emerged as the third challenge, she noted. She explained that this challenge in particular limits the application of secondary prevention strategies that are typically used in the public health sector—namely, screening people in order to detect and treat conditions at an early stage. Thus, the limited evidence available about risk factors obstructs secondary efforts to detect and intervene with people who have the propensity for violent extremist behavior. Essentially, this involves screening people in the precriminal space, because population-level screening for violent extremists is not currently feasible.

Lin explained that without the ability to screen as a secondary prevention strategy, the researchers developed a theory of change that spans the primary, tertiary, and quaternary domains. She detailed how in Boston the theory is informed by feedback from stakeholders about how to define the program’s success, which falls into three broad categories. The first category, building trust and earning social support, addresses the stakeholders’ need to be listened to and have their opinions validated, their desire to prevent profiling, and their suggestion to expand community policing. She explained that the second component is designed to address the second category, fostering civic engagement and cultural awareness. Such activities include the provision of safe spaces for encouraging civic conversation and open forums for nonmainstream discussions, increasing diversity in the system (that is, government, social service providers, and schools) and improving cultural sensitivity, as well as developing counternarratives against violence and discrimination. The third category, according to Lin, comprises activities to treat the root causes of violence and violent extremists by improving conditions to the extent that people can reach their full potentials; this includes investing in school system and education initiatives, expanding youth programs and services, addressing housing issues, and nurturing healthy and safe neighborhoods.

Looking forward, Lin reported that in August 2016, the Massachusetts Executive Office of Health and Human Services issued a request for proposals (RFP) for the Promoting Engagement, Acceptance, and Community Empowerment (PEACE) Project to be implemented in Boston. Its goals are to prevent violence (and prevent people from joining organizations that promote, plan, or engage in violence) as well as to promote resilience by

strengthening protective factors. She commended the organizers for incorporating stakeholder feedback that was shared with them by the researchers of the evaluation pilot program. Specifically, the most recent RFP for the PEACE project focuses on primary (rather than secondary) prevention and completely excludes concepts such as CVE, radicalization, ideology, and risk factors. She explained that instead, the RFP pinpoints specific results and provides clear definitions of violence and violent extremism as “an act that violates state or federal law and causes physical harm to a person, or property and is motivated by hate and/or the intention of domestic terrorism.” She noted that the pilot program has offered its resources for technical support should the PEACE project choose to have an evaluation component of its program.

Evaluating the Capacity of the Mental Health Sector to Support the CVE Enterprise

Stevan Weine, a professor of psychiatry, the director of the International Center on Responses to Catastrophes, and the director of Global Health Research Training at the Center for Global Health, University of Illinois at Chicago, remarked that many new community-based initiatives to address violent extremism are seeking to engage the mental health sector. He described efforts to incorporate the mental health sector into activities to address both violent extremism and violence writ large within the Los Angeles CVE framework. Because a very large proportion of lone actors who commit violence have mental health and psychosocial problems that necessitate mental health intervention, Weine noted, it is a challenge to find the sufficient organizational capacity and professional expertise to conduct mental health interventions of the scope needed for CVE. According to Weine, there is not yet a credible consensus model to implement and support this work in a way that protects civil rights and civil liberties.

Project Eval LA, a collaboration with UCLA, is a partner of the Los Angeles Region Intervention Steering Committee,12 and it has prepared a forthcoming formative evaluation report assessing intervention efforts in Los Angeles.13 Weine shared some of the preliminary findings of the report.

___________________

12 As discussed by Joumana Silyan-Saba earlier in the proceedings, the Los Angeles Region Intervention Steering Committee is convened and coordinated by the Los Angeles Mayor’s Office in partnership with the DHS LA Regional Office. It has used a joint public health and mental health approach to help augment the Los Angeles CVE framework by building logic models, a services flow chart, evaluation tools, training plans, and other types of supporting materials needed to implement a program.

13 He explained that such reports are commissioned to ensure that a given program is well formed, is well developed, has clear goals and objectives, has clear outcomes and outputs, has a hypothesized process based on sound theory, and is evaluable.

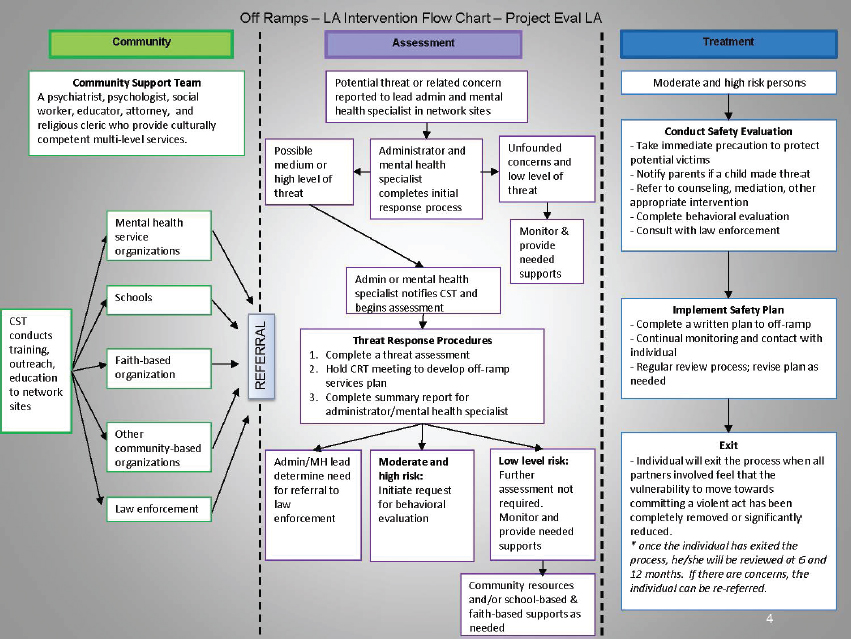

Proposed Los Angeles CVE Intervention Services Flow Chart

Weine presented the services flow chart created by the steering committee, which is subdivided into the three domains of community, assessment, and treatment (see Figure 5-6).

Weine explained that the services flowchart draws heavily on a threat assessment framework used by the School Threat Assessment Response Team program14; it is not based on radicalization theory but on a pattern of communications and behaviors that people exhibit prior to committing violent extremism. He explained that within the community domain, a community support team composed of multidisciplinary professionals accepts referrals from a wide range of organizations, conducts threat-assessment training, and forges links with a broad network of professionals or paraprofessionals from various organizations. In the assessment domain, a community-based professional (for example, a school or workplace psychologist) conducts the first level of assessment to determine if there is a credible problem that warrants referral to the community support team for further threat assessment and behavioral assessment, or if other types of care or support are appropriate. In the treatment domain, Weine explained, people who have been screened as having a medium to high level of threat, based on established criteria,15 receive a thorough threat assessment, a behavioral assessment, and a safety plan, all of which are implemented by the community support team. People referred for care receive ongoing case management, law enforcement referral (if needed), social support services, mental health services, a follow-up plan, and a plan for eventual exit from the program as appropriate.

Tabletop Exercise to Assess Mental Health Capacity

According to Weine, the steering committee has grappled with whether the program should be a targeted violence program that incorporates school violence, workplace violence, and hate crimes, rather than focusing exclusively on violent extremism. To explore this possibility, he reported that the steering committee has plans under way to work with LA County DMH to expand the school violence program into a broader violence prevention program that includes expertise on violent extremism.16

As part of that process, a pair of tabletop exercises were conducted in

___________________

14 Run by the LA County Department of Mental Health Emergency Operations Bureau.

15 In a given year, he reported that the department receives between 3,000 and 4,000 referrals for assessment; around 100 people considered to be medium or high risk are screened.

16 He noted that the DMH is the only organization in Los Angeles with the capacity and professional expertise to perform this type of intervention work on the large scale required (10 million people in 188 cities within Los Angeles County).

NOTES: CRT = Community Response Team; CST = Community Support Team; MH = mental health. This proposed flowchart was not ultimately adopted by Los Angeles.

SOURCE: Weine presentation, September 8, 2016.

July 2016 to assess the performance of the DMH in a CVE situation by using two simulated scenarios of violent extremism. During the exercise, teams of multidisciplinary partners discussed decisions such as determining the veracity of the threat, which types of services to recommend, whether law enforcement should be involved, and how to deal with the community.

Weine reported that the tabletop exercise revealed an instructive panoply of existing capacities and gaps in capacity. It identified 23 existing capacities: for instance, multidisciplinary teams were well established and proficient in working with community members and professionals from multiple disciplines, and the evaluation teams were able to conduct thorough threat and behavioral assessments and cooperate effectively to plan assessments and treatments. However, Weine noted that twice as many gaps (46) were identified as capacities. These included the cultural competency of care regarding Muslim Americans, use of measures and tools, how to make referrals and dispositions, activation and coordination with community leaders and organizations, and monitoring and responding to media.

According to Weine, the exercise revealed that mental health and public health services can make key contributions to targeted violence reduction. Instead of focusing on a very small number of people who may potentially commit acts of violent extremism, the focus with targeted violence reduction is on a larger number of people, organizations, and providers involved in violence prevention.

Finally, Weine suggested that tabletop exercises can be an effective way to jumpstart the implementation of targeted violence reduction programs through engagement with the mental health sector, by fostering trust among disparate stakeholders and community partners,17 and by exposing capacities and gaps to be addressed.

THE ROLE OF HEALTH PROFESSIONALS IN CVE: LEGAL AND ETHICAL ISSUES

Participants discussed the landscape of health professional ethics within the CVE space, focusing on the roles and responsibilities of health professionals with respect to threat assessment and obligatory reporting. Runnels observed that there seems to be a tension between what it means to be a health practitioner involved with CVE and what it means to be someone who does research in these areas, in terms of ethical issues, legal concerns, and the pressures to build an evidence base and actually take action by implementing programs and measures.

___________________

17 Weine reported that during the exercise, the strongest critics of CVE were impressed at the sensitive way in which law enforcement, mental health professionals, and others were able to parse the evidence, make determinations, and share (or not share) information.

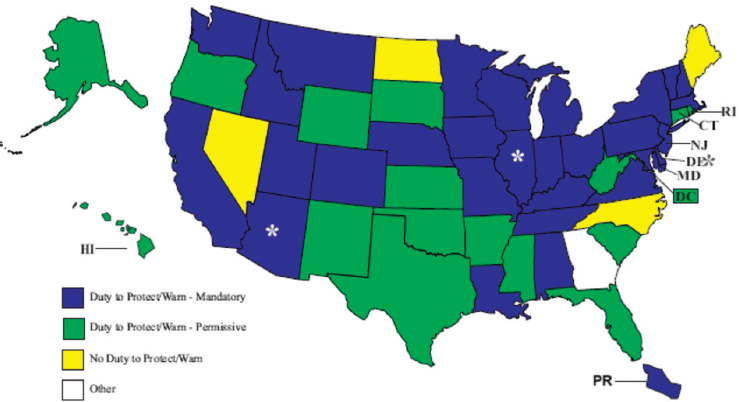

Legal Reporting Obligations for Health Professionals

Wynia noted that incidents of extremist violence often spawn legislative attempts to mandate health providers to report on individuals they believe to be dangerous, citing the wave of bills passed in California, New York, and Tennessee in the wake of the 2012 Sandy Hook massacre.18 Hick observed that there are difficult questions to answer with respect to the specific role of health professionals in reporting suspicious issues, such as whether and when to engage law enforcement. He explained that legal requirements regarding whether the duty to warn and the duty to protect are obligations for providers vary by state (see Figure 5-7). In states where both types of reporting are obligatory, if a health provider witnesses any specific threat or thinks there is the probability of a violent occurrence, then it must be reported to the relevant responsible public enforcement agency and the person at risk must be informed.

Hick explained that the 1976 case Tarasoff v. Regents of the University of California served as the catalyst for many of the laws concerning the duty to warn and the duty to protect. The case involved a student in California who reported to his psychologist that he was going to kill his female peer. The psychologist reported the claim to law enforcement, but the psychologist did not inform the student that was at risk and her family. He killed the woman when she returned to campus after a study abroad program; her family sued and won a judgment in the case. In the years since, Hick noted that most states have implemented Tarasoff-like laws that oblige health professionals to report specific and probable threats made by their patients. He continued that in many states, medical providers must report any gunshot wound unless law enforcement is already involved, as well as any cases of suspected domestic violence, child abuse, or child neglect. Wynia noted that there are further legal criteria that can be used to breach personal liberties in certain circumstances. For example, HIPAA allows for disclosure to law enforcement with a warrant, including provisions for “intelligence and national security activities” to assure “proper execution of a military mission,” and to “provide protective services to the President.”

___________________

18 New York requires mental health professionals to report anyone who “is likely to engage in conduct that would result in serious harm to self or others” to the state’s Division of Criminal Justice Services, which then alerts the local authorities to revoke the person’s firearms license and confiscate his or her weapons. California mandates a 5-year firearms ban for anyone who communicates a violent threat against a “reasonably identifiable victim” to a licensed psychotherapist. Tennessee requires in-state mental health professionals to report “threatening patients” to local law enforcement, which was passed “in response to mass shootings.”

NOTE: Green: permitted to report; blue: obligated to report; yellow: no obligation to report.

* Arizona, Delaware, and Illinois have different duties for different professions.

SOURCES: Hick presentation, September 8, 2016; available at http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/mental-health-professionals-duty-to-warn.aspx (accessed November 8, 2016).

Potential Consequences of Obligatory Reporting for Individuals and Communities

Wynia highlighted the tension between the dual loyalties both inherent and pervasive in health care. Because a small number of people do pose a threat that warrants reporting, health professionals are tasked with striking a delicate balance between their social responsibilities and their duties of care. He emphasized that legislatively mandated reporting inevitably leads to overreporting and false positives, because providers are concerned about the severe consequences of failure to report a patient who goes on to commit violence. However, he pointed out that a false positive report can have a similarly devastating effect on the lives, families, and careers of patients who are reported and then found not to be a threat. Obligatory reporting can also compromise the therapeutic process, according to Wynia, which often requires verbalizing hostile impulses in presumed confidence.

Taking a step back, Wynia observed that there is historical precedence for the practice of requesting (or requiring) health professionals to serve as agents of the state in pursuit of social policy aims under the pretext

of protecting the community. He provided several examples to illustrate. The 19th-century diagnosis of drapetomania was applied to slaves who made “unreasonable” repetitious attempts to escape. California’s Prop 187, which was never actually implemented, required physicians to report patients seeking care without appropriate documentation of legal immigration status. In Pakistan, a fake hepatitis B vaccination campaign was designed to gather intelligence on Osama bin Laden; as a result, Pakistan is now home to 60 percent of the world’s polio cases after trust in the vaccination enterprise was decimated. In 2013 in New Mexico, at least three people were brought into the hospital under suspicion after routine traffic stops and subjected to rectal exams, colonoscopies, and CAT scans—none of which resulted in any evidence of criminal activity.

Wynia reiterated that missteps and overreach in this arena can be catastrophic for patients, referring to the U.S. Supreme Court case of Buck v. Bell (1927), which justified the forced sterilization of Carrie Buck. In his decision, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes stated:

We have seen more than once that the law may call upon the best citizens for their lives. It would be strange if it could not call upon those who already sap the strength of the State for these lesser sacrifices . . . in order to prevent our being swamped with incompetence. . . . The principle that sustains compulsory vaccination is broad enough to cover cutting the Fallopian tubes. Three generations of imbeciles are enough.

The issue persists today, noted Wynia, who is member of a panel for the American Psychological Association (APA) that is considering how to respond to the Hoffman Report, which showed that key leadership and staff at the APA colluded in the coercive interrogations program during the Bush administration, which included aspects of research on how best to torture people.

Hick remarked that making a report that turns out to be false can have severe and unintended consequences not only for the individual, but for the cultural community at large. Hick cited the example of an emergency medical services (EMS) crew being called to transport a woman who was ill from an apartment complex in Minneapolis in which the majority of residents were Somali. The crew noticed large amounts of electronic supplies, metal cylinders, and other initially suspicious items; they reported it to their supervisor and then to the police. Ultimately it was determined that a man living in the apartment was a radio control vehicle enthusiast. The situation was resolved, but according to Hick, it undermined relations between the EMS and other residents of the apartment complex (e.g., instead of allowing crews to enter to their apartments, residents would bring the family member needing care down to the lobby). He remarked that although the incident was well intentioned, it created a major trust problem.

He suggested that while failing to report a threat that comes to fruition in a terrorist attack can have severe consequences, there needs to be appropriate care taken in reporting suspicious activity.

Hick further noted that suspected child neglect can sometimes require a nuanced understanding of cultural context because it can expose the discrepancies between Western medicine and medical traditions of immigrant communities. He explained that providers are protected from legal repercussions if the report is in good faith, but that does not mitigate potential cultural backlash. For example, reporting can result in the state taking protective custody of children who are considered to be at risk based on Western medical criteria but whose parents decline further diagnostics or interventions. He commented that this can severely destabilize the immigrant community’s trust in providers (which has happened in both the Hmong and Somali communities in Minneapolis).

Wynia remarked that despite the tenets of the Hippocratic Oath, in which protecting patients’ privacy and confidentiality is a key principle, upholding confidentiality is not an absolute value for health professionals. He emphasized that there are no absolute values in biomedical ethics. He explained that the most common means of analyzing ethical problems in medicine is called principalism, which involves balancing all the relevant principles to optimize the overall outcome while conceding that not every principle will be optimized. In the realm of ethics, remarked Wynia, the key criteria in determining when it is ethically justifiable to breach confidentiality include credible threat, significant harm, the presence of an identifiable third party, and the likelihood that the warning will be effective.

Practical and Ethical Challenges in Individual Threat Assessment: Health Approach Perspective

Can Health Professionals Predict Violent Behavior?

Health professionals’ poor ability to accurately detect a credible threat is a critical concern, according to Wynia, particularly when the determination is used as justification for breaching civil liberties. He cited data from the 1970s suggesting that physicians are no better than chance at predicting whether an individual will become violent. That said, he conceded that the best possible study design to examine that capability would be completely unethical because it would require tracking individuals who are predicted to be dangerous while letting them roam free. However, he noted that a 1967 U.S. Supreme Court decision (Baxtrom v. Herold) released 967 “criminally insane” patients from prison because they were not receiving therapy for

their mental illnesses, despite being evaluated annually for dangerousness.19 The patients were tracked for 4 years after their release, and only 2.2 percent (n = 21) were returned to prison for any criminal act (error rate ~97 percent). A subsequent study (Lidz et al., 1993) revealed these types of predictions of violence have poor differential ability, reported Wynia. Of 357 patients who were tracked in the study, 53 percent of the individuals whose psychiatrists predicted they might commit violence did so within 6 months; however, 36 percent of patients predicted not to be violent actually did commit violence.

Wynia reflected that although practitioners and studies do have a very difficult time accurately predicting individuals who are going to commit violence, it is not impossible. He pointed to the human instinct that makes us feel that it is possible to tell when a person you observe is potentially dangerous. Benjamin commented that individual threat assessment is contingent on a clinician’s ability to be astute in the difficult task of “connecting the dots” to recognize that an individual is in the spectrum of threat. He observed that further upstream, public health focuses on risk assessment by astute citizens who “see something and say something.” Both approaches need to be further refined. Miller raised the issue of how exposure to vicarious trauma may lower the threshold for health care providers’ perception of individual-level and community-level threats. Stewart suggested that the poor ability to predict violence may be attributable to the wrong questions being asked or, perhaps, because it is not predictable at all, despite how counterintuitive that may seem.

Hick explained that the types of credible or probable direct threats for which providers are routinely vigilant are different than the suspicious activities they are asked to report with respect to the threat of violent extremism. CVE threats also have a slightly different threshold. Hick noted that in other contexts, providers are given anticipatory guidance (e.g., questions about suicide risk or domestic violence) that is based on known risks and relatively well-established community-wide interventions with known efficacy. In the CVE space, he explained, it is very difficult to select the appropriate interventions and to select the population at risk. He suggested that by the time an individual’s behavior raises red flags that are sufficient for a health care provider to act from legal and other obligatory standpoints, there are often concerns over whether the evidence is sufficient to mandate an assessment or to place restrictions on that person. He expressed doubt that there is much scope for health care providers (from a recognition and treatment standpoint) to do more than perform the types of mental health

___________________

19 In addition, they had spent more time in prison than they would have had they been convicted of their original crime rather than being judged criminally insane.

threat assessments that are already standard practice, without giving rise to significant ethical concerns.

Hick noted that a common criticism leveled against threat assessment is that certain factors can be more heavily weighed and thus prone to subjective bias, but he remarked that this is also a problem with most psychological assessments. He contended that many nonmental health providers have an instinctive feeling about patients that factors into risk assessment; even though there are some criteria they consider when performing assessments, it is by no means a rigid proscriptive set of criteria.

Threat Assessment Methodology and Expertise

Weine observed that the threat assessment field grapples with the issue of whether the people being targeted in CVE interventions are the same people who go on to commit violence, and if efforts should be targeted on a specific subset of people. He advised that there must be a way to differentiate between a person with an overt and potentially modifiable emotional disturbance who is also considering violent behavior, and a person who is a committed criminal who has just not acted violently yet; only the former person would be responsive to CVE-type case management or treatment.

Runnels noted that public health tends to focus its efforts on the broader community, and questioned what the implications of an individual risk assessment strategy would be when dealing with larger populations. Lin explored the issue of population-level screening for violent extremism in her presentation. She explained that a screening program is only as good as the predictive ability of the risk factors on which the population being screened is based. It is also heavily dependent on the prevalence of what is being screened for, so screening is not usually feasible for rare outcomes. The key question in considering a screening test for violent extremism, she explained, is to determine how likely it is that a person with a positive test result is actually a violent extremist. She described the following thought experiment to illustrate the answer.

As of 2016, the United States population was 323 million, including a presumed 10,000 violent extremists. If there were an extremely powerful hypothetical screening test that could pick up 99 percent of violent extremists when screened, then screening the population would identify 9,900 violent extremists (true positives) and miss 100 of them (false negatives). If the hypothetical test also had a 99 percent specificity, then the test would correctly identify more than 320 million people as innocent (true negatives). However, it also means that more than 3.2 million people will be incorrectly labeled as being violent extremists despite being innocent, which is an extremely high number of false positives. In statistical terms,

the positive predictive value of this very powerful hypothetical screening test is just 0.3056 percent.20

Thus, Lin concluded that population-level screening for violent extremism is not possible at the current stage. She clarified that no screening test with 99 percent sensitivity or specificity actually exists; generally, these types of tests have specificity of between 70 percent and 80 percent.

Wynia noted that individual threat assessment does not typically employ population-level strategies because they do yield such high numbers of false positives. Instead, they target a very rich sample of individuals in clinics and emergency departments who have a high probability of violence prior to screening, which makes testing that sample worthwhile. Wynia stated that a specificity level of 70–80 percent is acceptable in a sample where the probability of disease is high: “If we start with 9 out of 10 people who are going to be doing something bad anyways, then having a 70 percent test is good enough.”

Hick commented that Bayes’ Theorem is also relevant: when testing a high-probability population for the presence of a disease, the performance of that test is likely to be much better and much more predictive; if the test is applied to everyone in the population regardless of risk, then the performance of the test becomes significantly worse and results in a tremendously higher number of false positives. He emphasized that deciding who should be screened is incredibly important, regardless of the performance characteristics of the test. Lin remarked that this type of testing is only one indicator that factors into clinical judgment and not its sole basis. She highlighted the importance of differentiating between assessment tools and diagnostic tests: assessment tools attempt to predict a future outcome (as in suicide assessment). Diagnostic tests confirm or determine the presence of a condition. Beyond clinical decisions, she argued, the focus should be on ethical issues as well as understanding the limitations of these tests in order to improve them.