1

Introduction

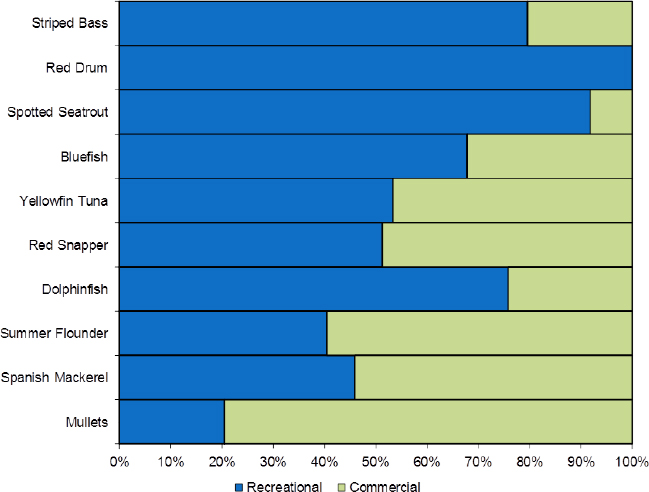

Over the past several decades, interest in the impact of marine recreational fishing on fish stock size and composition has increased (NRC, 1999, 2000, 2006; Lucy and Studholme, 2002; Coleman et al., 2004; Ihde et al., 2011). The recreational sector accounts for a substantial portion of the total catch in several fisheries, even exceeding the commercial catch for some species (Figure 1.1). However, several attributes of the recreational sector make it more difficult to assess and evaluate than the commercial fishing sector (NRC, 2006). This is, in large part, because there are many more recreational anglers than commercial fishermen, and the recreational sector uses a much larger number of access and landing points, on both public and private property.

THE FISHERIES MANAGEMENT CONTEXT

Because of the increasing concern about the effects of recreational fishing on fish stocks, the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has tried for more than three decades to collect and analyze data on recreational fishing. It has done this mainly through survey programs; first, through the Marine Recreational Fisheries Statistics Survey (MRFSS), and then, following a review of that program by the National Academies in 2006, through the Marine Recreational Information Program (MRIP).

Obtaining reliable data is a challenge, for the reasons mentioned above. In addition, recreational fisheries are only part of the overall fisheries management endeavor in the United States, which is a complex and multifaceted set of activities among federal, state, and joint organizations. As a result, the MRIP is not

implemented in a vacuum and cannot be evaluated that way. It is, and should be evaluated as, an integral part of the larger U.S. fisheries management endeavor.

To further complicate matters, the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (MSFCMA), the federal statute under which marine fisheries are managed, was reauthorized in 2007 with a new emphasis on avoiding overfishing and on rebuilding overfished stocks. It achieves these goals by implementing Annual Catch Limits. This changed the context of fisheries management in the United States by providing demands to limit catch, including recreational catch. As described in more detail below and in Chapter 6, this new fisheries management context changed the way that marine recreational fishery data are used. Below is a summary of the context for marine recreational fishery data (i.e., the MRIP) within the broader and more complex endeavor of fisheries management in the United States.

Federal Fisheries Management

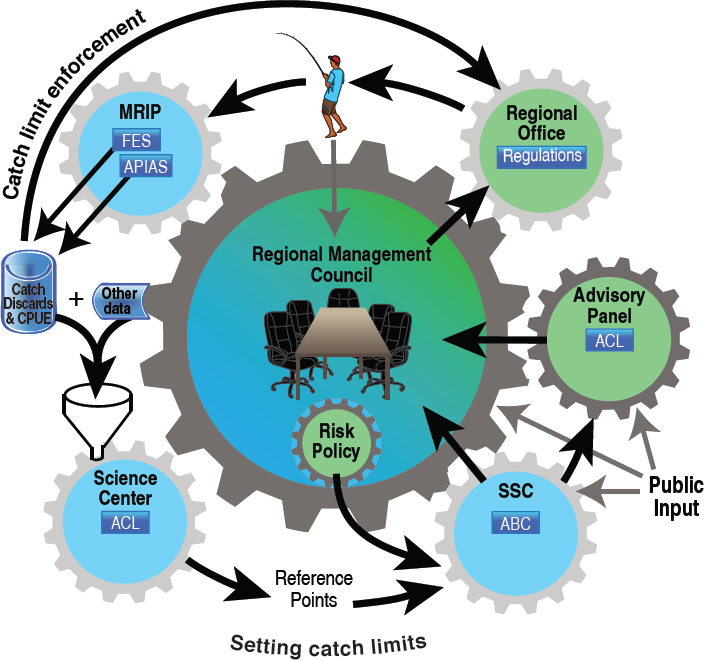

Marine fisheries management is a complex, interdisciplinary challenge (Figure 1.2). It involves numerous stakeholders including fishers, environmental

stakeholders, social and natural scientists, and managers. All agents in Figure 1.2 play essential roles by providing data, analyses, or advice and/or by implementing regulation. The figure emphasizes the involvement of recreational fisheries in the management process.

The MRIP is but one component of the fisheries management challenge depicted in Figure 1.2. The MRIP’s role is to estimate recreational catch and discards of fish from the population. Discards are the fish that are released, and include those released relatively unharmed as well as those that are dead or will not survive. The total number of fish that die as a result of being caught or dis-

carded is termed the removals. Recreational catch is estimated using statistical approaches to estimate the number of recreational angler fishing trips (effort), the average catch per trip (catch per unit effort [CPUE]), and the average number of discards per trip. The product of effort and CPUE provides an estimate of the recreational catch. The product of effort and discards per trip is weighted by an estimate of the mortality rate to estimate the total discard mortality. Additionally, CPUE in the recreational fishery is often used as an index of the abundance of the targeted species, because it is often difficult to develop reliable estimates of abundance independent of the fishery for many recreational species.

The outputs from the MRIP are used by stock assessment analysts to assess the status of the exploited fish population (Figure 1.2). A stock assessment is a mathematical representation of the population, the components of which are estimated statistically by fitting the model to observed data (Quinn and Deriso, 1999). In addition to the data from the MRIP, a stock assessment typically involves fishery-dependent data on removals (catches and discards) in commercial fisheries, data from fishery-independent surveys of abundance of the targeted species, and biological data on the targeted species. The objective of the assessment is to estimate the population abundance, fishing mortality, and stock status. The assessments are further used to determine maximum sustainable exploitation rate (when expressed as catch, this is termed the overfishing limit or OFL) and the minimum abundance that is sustainable for the species (termed the overfished limit). These estimates are reference points and are at the heart of federal fisheries management under the MSFCMA, which requires fisheries managers to avoid overfishing (i.e., not exceeding the OFL) and rebuilding stocks that are below the overfished level (MSFCMA; NMFS National Standard 1 Guidelines).1

The MSFCMA requires that each of the eight regional fishery management councils establish fishing policies that limit to 50 percent or lower the risk of exceeding OFL for each managed species. This is termed the council’s risk policy (Figure 1.2). It is the responsibility of each council’s Scientific and Statistical Committee (SSC) to use the best available science to provide a recommended Acceptable Biological Catch (ABC), which integrates the most up-to-date understanding of the status of the population of the exploited species and the Council’s risk policy such that the ABC ≤ OFL to account for scientific uncertainty.2 Each council appoints suitable qualified people, often highly trained quantitative scientists, to the SSC.

Implementation of a recommended ABC is unlikely to be perfect because of structural difficulties in regulating catch—particularly for recreational species. Accordingly, the councils are required to establish an Annual Catch Limit (ACL) such that ACL ≤ ABC ≤ OFL.3 Councils may account for uncertainty in the implementation of their management actions by establishing an Annual Catch

___________________

1 16 U.S.C. §1851; 50 C.F.R. 600.310 (2009).

2 16 U.S.C §§1852(g)–(h).

3 16 U.S.C. §1852(h).

Target (ACT). For many councils, the task of establishing ACLs and ACTs is undertaken by an advisory panel composed of a diverse set of stakeholders that might include recreational fishers (Figure 1.2).

Ultimately the ACL and ACT adopted by the Council are provided to the regional NMFS office, which, acting on behalf of the Secretary of Commerce, determines the acceptability of the recommended ACL and ACT and promulgates regulations.

The MSFCMA introduced new requirements that mandate accountability measures should the ACL be exceeded.4 For species subject to recreational fisheries, this has placed a new demand on estimates of recreational catch—to be used not only to develop OFLs, but also to ensure compliance with Council-established catch limits (Figure 1.2). The temporal and spatial demands on estimates of total annual removals for stock assessment purposes may not match the scale needed to assess when catch limits have been exceeded, requiring implementation of accountability measures.

Combined Federal and State Jurisdiction

Many species subject to recreational fishing are subject to joint federal and state jurisdictions. In such cases, a combination of appropriate agencies cooperatively manages the fisheries. However, the federal model described in Figure 1.2 is increasingly being used to manage fisheries under joint federal-state jurisdictions and even for fisheries solely under state jurisdiction. Often a single stock assessment is conducted that assumes a single, well-mixed population that is uniformly distributed throughout the region of interest, although increasingly spatially explicit models are being explored. The integrated assessment model generates a single, stock-wide ABC. These ABCs are translated through regulatory bodies into single, stock-wide ACLs and ACTs, together with regional or sector-based allocations of the ACT to each partner jurisdiction. The allocation of the ACT to regions is often based on historical patterns, and in the rapidly evolving recreational fishing sector, these allocations can be contentious (Morrison and Scott, 2014).

A separate consideration involves species managed under international governance, for example, Pacific salmon and Pacific halibut. Although the process of arriving at ACLs may differ somewhat from domestic processes, the underlying data collection and stock assessments follow science-based approaches similar to those used by U.S. agencies. However, MRIP data retain an important role in informing domestic allocations in such internationally managed stocks.

___________________

4 16 U.S.C. §§1853(a).

MARINE RECREATIONAL FISHERIES STATISTICS SURVEY

In 1979, NMFS established the MRFSS as a national program for obtaining standardized and comparable estimates of participation, effort, and catch within the marine recreational fisheries of the United States. The stated objective of the MRFSS was the development of a reliable national database that could be used to estimate the impact of marine recreational fishing on marine resources.5

The MRFSS collected data using two independent but complementary surveys, a telephone survey and an in-person intercept survey (NRC, 2006). NMFS used the telephone survey to gather information about individual anglers’ fishing trips to determine the amount and types of fishing that occurred within a 2-month period, including the number, modes, access types, and dates of recreational fishing trips. The surveys inquired only about the preceding 2 months, assuming that anglers’ recollections of their activities beyond 2 months were not sufficiently reliable.

The second survey used by the MRFSS was an in-person intercept survey, whereby trained field staff interviewed anglers at sites where anglers access and leave the water, such as marinas, docks, piers, or beaches (NRC, 2006). These intercept surveys were used to collect information on catch, including species, weight, length, and number of fish caught by anglers. In some cases, the onsite intercept survey was also used to collect additional biological information or samples.

Because the in-person intercept survey did not capture all anglers, and because little was known about the characteristics of the anglers sampled and those missed (to assess bias in the survey results), it was not possible to obtain a reliable estimate of total catch from the in-person intercept survey alone (Chapter 2 discusses this and other sampling issues in detail). Instead, the intercept survey was used to estimate CPUE, that is, the number of fish likely to be caught for a given unit of fishing activity. The telephone survey was required to obtain an independent estimate of angler fishing effort (E). Together, the data collected from the two surveys were used to provide estimates of total participation, effort, catch, and CPUE for six 2-month periods each year.

In addition to the intercept and telephone surveys designed and implemented by the MRFSS program, at least 13 other supplemental or component surveys were conducted by federal or state agencies to ascertain marine recreational fishery catch and effort. These additional surveys were funded at least in part through the MRFSS program and were intended to produce data that were compatible with MRFSS objectives, although the methodologies and statistical techniques often varied from the core telephone and intercept surveys conducted under the MRFSS. These additional surveys were developed as a way to better meet the data needs of a particular region or sector (NRC, 2006). Alaska has never been

___________________

5 See http://www.st.nmfs.noaa.gov/recreational-fisheries/MRIP/program-evolution.

part of the MRFSS program, and Texas has not been a part since 1985; both conduct their own surveys.

Since the development of the MRFSS program in 1979, the context for conducting recreational fisheries surveys and the uses of survey data have changed significantly for the nation’s fisheries. As exploitation levels increased, fisheries became more highly regulated, and management decisions were increasingly made at finer spatial and temporal scales (NRC, 2006; Breidt, 2013). Additionally, the mix of recreational and commercial fishing has changed over the years in many regions and for many species. By the early 2000s, some stakeholders had expressed concern that recreational data collected through the MRFSS and other recreational fishing surveys were being incorporated into management in ways that exceeded the original design and purposes. They also expressed concerns about the precision, robustness, and timeliness of the data collected through the MRFSS relative to the data needed for effective management (NRC, 2006).

2006 STUDY: REVIEW OF RECREATIONAL FISHERIES SURVEY METHODS

In 2004, NMFS requested that the National Research Council (NRC; now known as the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine) review data collection for marine recreational fisheries in the United States, and specifically, the MRFSS. The NRC assembled a committee of ten experts in fishery science and statistics, which released its report, Review of Recreational Fisheries Survey Methods, in 2006 (NRC, 2006; see Appendix B for a summary of that report). The report recommendations were categorized as sampling issues, statistical estimation issues, human dimensions, program management and support, communication and outreach, and general recommendations.

Overall, the 2006 report called for a considerable redesign of the survey program to modernize the survey methods to reduce bias, increase efficiency, and build greater trust and relationships with the recreational angling community. The report acknowledged the tremendous complexity of the challenges associated with implementing a survey program such as the MRFSS and in performing statistical analyses with the resulting data. Given these challenges, the report concluded that substantial, additional resources would be necessary to revise and improve the survey program.

THE CURRENT REVIEW

The Fishery Conservation and Management Act of 1976 has been amended and reauthorized multiple times, and is now known as the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act. In the most recent reauthorization,6

___________________

6 Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Reauthorization Act of 2006, Publ. L. No. 109-479 (2007); 16 U.S.C. §§1801–1884.

Congress called for a “regionally based registry program for recreational fishermen in each of the eight fishery management regions.”7 The act further mandated that the Secretary of Commerce, “in consultation with representatives of the recreational fishing industry and experts in statistics, technology, and other appropriate fields,” develop a program for making improvements in the quality and accuracy of the MRFSS.8 The legislation particularly called for the program to implement, to the extent feasible, the recommendations of the NRC’s 2006 report (see Appendixes B and C for a summary of that report and a table of its recommendations).

Since 2007, NMFS, in response to the reauthorization, has worked to improve the survey program by developing a national saltwater angler registry and transitioning from the MRFSS program to the redesigned MRIP. The redesigned MRIP includes a separate offsite Fishing Effort Survey (FES) to assess effort and an Access Point Angler Intercept Survey (APAIS) to gauge CPUE. Although the basic structure is similar to the MRFSS, major changes have been made to the methodologies and statistical analyses used for both the FES and APAIS.

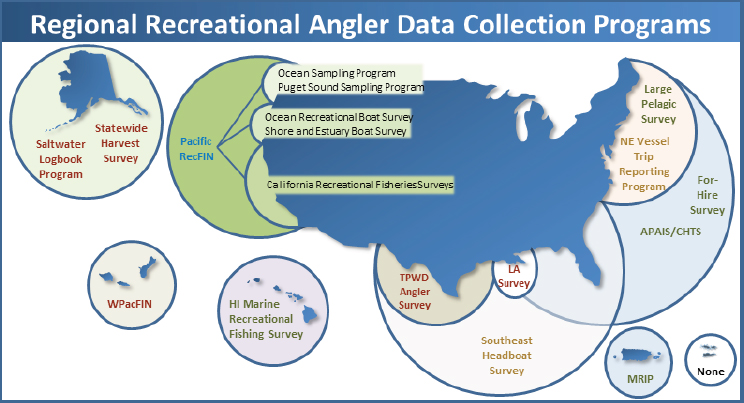

The MRIP also funds and provides technical support for a variety of region-, state-, species-, and sector-specific surveys that either supplement or serve as alternatives to the APAIS and FES (Figure 1.3). NMFS has had to consider how to allow for these individual surveys, which may be better tailored for specific circumstances, while also maintaining sufficient data consistency for management.

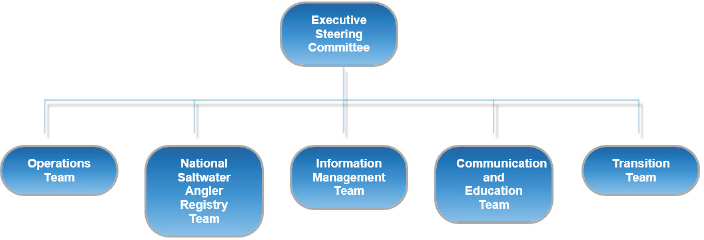

To support this more inclusive and integrative implementation approach, the MRIP is managed via a team structure, under the guidance of an Executive Steering Committee (ESC). To ensure transparency and to achieve customer and stakeholder support, the ESC and the MRIP teams comprise members from NMFS headquarters, its regions and Fisheries Science Centers, and state agency and Interstate Marine Fishery Commissions staff. In addition, the teams are joined by participants from the regional Fishery Management Councils and key stakeholder organizations such as national recreational fishing organizations (e.g., Coastal Conservation Association). The Communications and Education Team also includes a representative from NOAA Sea Grant (Figure 1.4).

Now, a decade after the release of the 2006 report, NMFS asked the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to conduct a second review to assess NMFS’s progress in addressing the 2006 report recommendations. In addition, NMFS asked the Academies to consider other aspects of the survey redesign, such as the strength of the scientific process and engagement with stakeholders (see Box 1.1 for complete statement of task).

The ad hoc committee assembled to address this task was composed of nine experts in fisheries science, fisheries management, stock assessment, statistics and survey design, and social sciences. They met on four occasions, in Washington,

___________________

7 16 U.S.C. §1881(g)(1).

8 16 U.S.C. §1881(g)(3)(a).

DC (February 24-26, 2016); Charleston, South Carolina (April 25-26, 2016); New Orleans, Louisiana (May 26-28, 2016); and Irvine, California (July 11-13, 2016). At each meeting, the committee heard from representatives from federal and state government, including MRIP staff and contractors; MRIP consultants; and regional stakeholders, such as anglers, nongovernmental organizations, and representatives from fishing associations and organizations. The committee also

received documents from NMFS and written input from stakeholders during the study process.

This report provides a general discussion of survey design and estimation considerations in Chapter 2. Chapters 3 and 4 provide more technical analyses of the statistical survey design and estimation procedures for the FES and APAIS, respectively. Chapter 5 discusses a framework for continued scientific evaluation, review, and certification. Chapter 6 explores the degree of coordination between the MRIP and other state and federal partners, and Chapter 7 provides an evaluation of the MRIP’s communication, outreach, and education efforts. Finally, Chapter 8 reviews plans for maintaining continuity of the data series despite changing methodologies. The appendixes in this report include committee and staff biographies; the summary of the 2006 NRC report; a table of the 2006 recommendations, indicating the most relevant chapter in this report for each and the committee’s ranking of NMFS responses; an excerpt from the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Reauthorization Act of 2006; copies of the survey instruments; excerpts from the 2014 Calibration Workshops; and a list of acronyms.