4

Changes in the Nature of Work and Its Organization

INTRODUCTION

Technological change affects more than productivity, employment, and income inequality. It also creates opportunities for changes in the nature of work itself. Numerous ethnographic studies have shown how a variety of new technologies have altered the way work is performed, the roles that workers play in a firm’s division of labor, and the way these changing roles alter the structure of organizations.1 In this chapter, the analysis of technology and society continues, with a focus on (1) changing forms of work, including occupations and contingent jobs; (2) dynamism and flexibility in the workforce; (3) demographics and job satisfaction; (4) the organizations and other institutions in which we work; (5) changes in the role of work in people’s lives; and (6) education and job training.

As the nature of the work environment continues to change, new trends have emerged at the individual, team, and organizational levels. The workforce is now more demographically diverse than ever, and

___________________

1 A. Aneesh, 2006, Virtual Migration: The Programming of Globalization, Duke University Press, Raleigh, N.C.; M. Baba, 1999, Dangerous liaisons: Trust, distrust, and information technology in American work organization, Human Organization 58(3):331-333; N. Natalia and E. Vaast, 2008, Innovating or doing as told? Status differences and overlapping boundaries in offshore collaboration, MIS Quarterly 32:307-332; S.R. Barley, 1990, The alignment of technology and structure through roles and networks, Administrative Science Quarterly 35:61-103; D.E. Bailey, P.M. Leonardi, and S.R. Barley, 2012, The lure of the virtual, Organization Science 23:1485-1504; S.R. Barley, 2015, Why the Internet makes buying a car less loathsome: How technologies change role relations, Academy of Management Discoveries 1:5-35.

older workers represent a significant subset of the working population.2 Increased technology and the growing complexity of tasks have given rise to more virtual and interdisciplinary teams.3,4 Furthermore, interest in multinational organizations has grown as many companies seek to increase their overseas assignments.5 If society is receptive to these changes and also able to adapt quickly to new technology, it can lead to benefits for both employees and organizations. However, history suggests that these trends can lead to hurdles and unexpected negative consequences, such as decreased job satisfaction, poor work/life balance, and neglect of personal and long-term career development.6,7 A brief summary of the most prominent trends within today’s workforce is discussed below.

THE ON-DEMAND ECONOMY

The rapid rise of firms like Uber, along with an increased recognition that IT permits individuals to connect and coordinate in unprecedented ways, have prompted great interest in the on-demand economy.

In the official aggregate statistics from U.S. statistical agencies, there is mixed evidence on the current role and extent of the on-demand economy. However, this may largely reflect a lack of clear measures of the relevant types of work.

U.S. statistical agency data, when controlled for cyclical variation, suggest that part-time work, multiple job holders, and short-duration jobs have not been rising. However, the number of companies with zero employees, which the U.S. Census calls “nonemployers,”8 has risen substantially over the last 10 years, from about 18.7 million in 2003 to 23 mil-

___________________

2 Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014, “Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey: Labor Force Characteristics 2014,” last modified March 10, 2016, http://www.bls.gov/cps/lfcharacteristics.htm#emp.

3 N.J. Cooke, E. Salas, J.A. Cannon-Bowers, and R. Stout, 2000, Measuring team knowledge, Human Factors 42:151-173.

4 L. Gratton and T.J. Erickson, 2007, “Eight Ways to Build Collaborative Teams,” Harvard Business Review, November, pp. 101-109.

5 R. Maurer, 2013, “International Assignments Expected to Increase in 2013,” Society for Human Resource Management, https://www.shrm.org/hrdisciplines/global/articles/pages/international-assignments-increase-2013.aspx; B. Frith, 2015, “Companies expect to increase international assignments,” HR Magazine, http://www.hrmagazine.co.uk/article-details/companies-expect-to-increase-international-assignments.

6 J. Wajcman, 2014, Pressed for Time: The Acceleration of Life in Digital Capitalism, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Ill.

7 P.F. Drucker, 2002, Managing in the Next Society, Truman Talley Books, New York.

8 Specifically, nonemployers are businesses that report revenue from business activity but do not have employees, and the newly self-employed may be showing up in this category.

lion in 2013;9 this category includes employees earning income as independent contractors (via Internal Revenue Service 1099-MISC forms). It has been hypothesized that many 1099 workers consider themselves as employees and report themselves as such in surveys, such as the Current Population Survey, yielding underreporting in certain categories.

Recent independent research found that the overall share of workers in alternative arrangements10 increased from 10 percent to about 16 percent between 2005 and 2015. Of these, less than 0.5 percent of the workforce (about 600,000 people) worked with online services, with Uber being by far the most common.11 However, the online sector, including a range of on-demand services, appears to be growing very rapidly and could account for millions of workers within a few years.12

The Internet-enabled on-demand economy is new, and the extent of its potential impact is as yet unknown. One challenge for monitoring this trend will be ensuring that the official statistics and other data available to the research and policy communities are adequate to capture the changing trends in the coming years.

One hypothesis is that individuals will increasingly provide their labor services in some form of independent contractor relationship with firms; independent contractors can now offer their services efficiently to a much bigger customer base. Alternatively, part of the on-demand or “gig” economy may be a new version of a personal service economy where personal services like transportation and delivery of food and other services are accessible through widely available technology on smartphones and other similar devices. For workers in the personal services component of the gig economy, such jobs may fit into a worker’s career in a variety of ways. They can be stopgap or secondary jobs, or, in some cases, their flexibility permits individuals to participate in the labor market to a greater extent than they would otherwise. However, note that Uber, the largest gig economy employer to date, has invested heavily in automation technologies and is already testing self-driving vehicles that could one day greatly reduce or even eliminate its need for human drivers.13

___________________

9 U.S. Census Bureau, 2015, “Nation Gains more than 4 Million Nonemployer Businesses Over the Last Decade, Census Bureau Reports,” U.S. Census Bureau Newsroom (blog), May 27, http://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2015/cb15-96.html.

10 These include independent contractors, workers at temporary help firms, on-call workers, and workers provided by contract firms.

11 L.F. Katz and A. Krueger, 2016 forthcoming, “The Rise of Non-Standard Work Arrangements and the Gig Economy?”

12 Remarks by Jonathan Hall (Uber Chief Economist) and by Larry Katz (Professor at Harvard) at the On-Demand Economy Workshop and Conference, MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy, Cambridge, Mass., March 14, 2016.

13 Reuters, 2016, “Uber Debuts Self-Driving Cars in Pittsburgh,” Fortune, http://fortune.com/2016/09/14/uber-self-driving-cars-pittsburgh/.

ORGANIZATION AND DISTRIBUTION OF WORK TASKS

Some production activities have historically taken the form of bringing groups of individuals together for specific projects, as in the construction and entertainment industries. The rise of IT-based work platforms that support new definitions and distributions of work tasks in new ways provides another illustration of the variable potential for application and use of technologies. Such platforms employ Internet-based communications and smartphone applications to make work available, and then assign that work to individuals or groups based on bid, proposal, or contest mechanisms. Crowdsourcing, open-call, and open innovation platforms can be used to redefine the nature of tasks themselves and to change how that work is organized and distributed both within and across organizational bounds.

Crowdsourcing platforms, for instance, work on the basis of tasks being decomposed into smaller units, even to the level of microtasks. These are then made available through open-call or auction mechanisms to people beyond strictly defined work teams or organizational bounds, including, but not necessarily beyond, a given firm. In addition, crowdsourcing mechanisms can be—and are—used within firms to open up the performance of work tasks broadly to their existing employees.14

Contest-based work solicitation systems, in contrast, operate by seeking solutions to often large-scale, complex challenges, but they too reach out to people beyond the boundaries of traditionally assigned job roles. And, although contest-based systems such as Innocentive support the outsourcing of work, such outsourcing is not necessarily inherent to this technological form. Like crowdsourcing, contests can be run internally at a firm among already salaried employees.

Even in the case of internal uses of crowdsourcing and contests, designing how work will be performed, managing both the processes and labor of production, and ensuring quality affects the work people do and how they do it. Managers may no longer have the same level of authority in managing where and how employees’ time is invested. Workers may find that their ability to control their own performance is more tightly circumscribed, or the opposite—they may be responsible for providing a particular output but be free to select how to arrive at that outcome. Collaborations and work relationships can be both forged and weakened by these mechanisms.15

___________________

14 M. Cefkin, O. Anya, and R. Moore, 2014, “A Perfect Storm? Reimagining Work in the Era of the End of the Job,” pp. 3-19 in 2014 Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings.

15 Ibid.

In general, IT can lower the costs of transactions and searches, which leads to more market-based interactions and temporary contracting.16 These developments suggest that the overall demand for work may not necessarily be threatened by technology, but rather that the shape of that work, and whether the tasks remain bundled into traditional “jobs,” is subject to change.17 This is especially evident in the rise of contingent labor.

CONTINGENT LABOR

“Contingent work” is a general term referring to nonstandard work arrangements, including temporary or contract work. Although contingent work is not new (firms such as Kelly Services and Manpower, for example, have been in the business of providing temporary clerical and industrial workers for many years), it has grown and attracted renewed attention recently with the online, open-call work platforms described above.18

Typically, contingent workers are not employees of the firms or people who profit from their services (although there are some exceptions). Contingent workers may be independent contractors or employees of staffing agencies that act as the worker’s employer of record for tax purposes.19 According to a recent report of the Government Accountability Office (GAO), approximately 7.9 percent of U.S. workers in 2010 were agency temps or on-call workers. A broader definition of contingent work, including part-time, self-employment, and other nontraditional work arrangements, would place the estimate at more than one-third of the 2010 workforce.20

Many workers prefer the flexibility, diverse income sources, and ability to control their work schedule and activities that are associated with employment via independent contracting, but this is not the universal

___________________

16 T.W. Malone, J. Yates, and R.I. Benjamin, 1987, Electronic markets and electronic hierarchies, Communications of the ACM 30(6):484-497.

17 Z. Ton, 2014, The Good Jobs Strategy: How the Smartest Companies Invest in Employees to Lower Costs and Boost Profits, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

18 M.C. White, 2014, “For Many Americans, ‘Temp’ Work Becomes Permanent Way of Life,” http://www.nbcnews.com/feature/in-plain-sight/many-americans-temp-workbecomes-permanent-way-life-n81071.

19 Some companies provide contingent workers as part of the payroll/tax service (so called professional employer organizations or PEO’s) but temporary staffing companies like Manpower have the full employer responsibility, including managing HR aspects of the employee.

20 C.A. Jeszeck, 2015, “Letter to The Honorable Patty Murray and the Honorable Kirsten Gillibrand: Contingent Workforce: Size, Characteristics, Earnings, and Benefits,” Government Accountability Office, http://www.gao.gov/assets/670/669766.pdf.

experience. Some contingent work is also “precarious,” which the committee defines as “uncertain, unpredictable, and risky from the point of view of the worker”21—for example, due to part-time or short-term employment, intermittent or unpredictable work hours, poor wages, or insecure jobs. The GAO found that “core” contingent workers (primarily agency temps and on-call workers) in the United States were “more likely to be younger, Hispanic, have no high school degree, and have low family income.”22 Over the last decade, for a significant share of the workforce, precarious positions associated with nontraditional employment models have become a permanent way of life. In fact, some argue that a new social class has risen from this trend, “the precariat,” made up of individuals facing insecurity, poverty, and a work life with no significance.23 In addition to gaining attention from the popular press, the rise of precarious work has led to a research stream investigating the consequences of temporary work. For example, in a review of studies on precarious employment conducted between 1984 and 2001, Quinlan, Mayhew, and Bohle found a negative relationship between precarious employment and occupational health and safety, concluding that it leads to a stressful and disorganized work environment.24

Contingent work relationships come in a variety of forms, involving various types of employment relationships and various types of worker benefits. Scholarship is at an early stage when it comes to analyzing the scope of contingent work and the implications of each type for employment structures, employment relations, and the welfare of workers. The use of IT-based platforms to access contingent work adds a new dimension to this category of employment.

For instance, there remains a vibrant business in providing temporary workers who fill in for sick or vacationing full-time workers or who are assigned to jobs for short periods of time to augment a firm’s full-time labor force when the firm finds itself understaffed yet unable to hire full-time employees. This contrasts with the highly skilled contractors and freelancers studied by Barley and Kunda and by Osnowitz, who work for longer periods of more than 6 to 18 months on projects inside a firm, often

___________________

21 A.L. Kalleberg, Precarious work, insecure workers: Employment relations in transition, American Sociological Review 74(1):1-22, 2009.

22 Jeszeck, 2015.

23 G. Standing, 2014, The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class, Bloomsbury Academic, London.

24 M. Quinlan, C. Mayhew, and P. Bohle, 2001, The global expansion of precarious employment, work disorganization, and consequences for occupational health: a review of recent research, International Journal of Health Services 31(2):335-414.

alongside full-time employees.25,26 Such contractors are typically compensated more per hour than full-time employees, after accounting for benefits. By hiring such individuals, firms relieve themselves of the costs of paying employment taxes, providing health insurance, contributing to pension funds, or investing in training. A technology-enabled platform, Upwork, provides highly skilled workers similar to high-tech contractors, except that the contractors are often located outside the United States and are subject to different labor laws and employment systems.

Other contingent workers use technology platforms to identify short-term and often unskilled personal service jobs for individuals who seek a service provider though websites or apps—for example, Uber drivers, those who perform odd jobs through TaskRabbit, or those delivering meals through GrubHub. These gigs may pay relatively little and are subject to unforeseen developments that may reduce their rate of pay. To make a living, gig workers require a steady stream of gigs.

Despite their diversity and the great variation in the duration of their projects, contingent workers often share a number of characteristics that place them outside the traditional system of employment relations in the United States, which assumes a long-term relationship with a single, stable employer. Many contingent workers receive no health-care benefits from their employers, receive no employer contributions to retirement funds, and are responsible for their own training and development as well as paying employment taxes.27 Staffing agencies may also extract a significant portion of revenue paid by clients for the contingent worker’s labor. Downtime between jobs is to be expected, although how well workers can manage or circumvent downtime depends on the type of contingent worker. Some contingent workers have a great deal of control over when they work, while others have very little control. Certain types of contingent work resemble the system of contract employment used in manufacturing during the late 19th century.28

Ensuring that the expansion of contingent work provides new opportunities for workers to control their work life, rather than leaving them

___________________

25 S.R. Barley and G. Kunda, 2004, Gurus, Hired Guns and Warm Bodies: Itinerant Experts in a Knowledge Economy, Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

26 D. Osnowitz, 2010, Freelancing Expertise: Contract Professionals in the New Economy, Cornell University Press, New York.

27 S.R. Barley and G. Kunda, 2004, Gurus, Hired Guns and Warm Bodies: Itinerant Experts in a Knowledge Economy, Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

28 On the role of outsourcing, contracting, and the putting out system in American factory production see D. Nelson, 1975, Origins of the New Factory System in the United States: 1880-1920, University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, Wisc.; J. Christiansen and P. Philips, 1991, The transition from outwork to factory production in the boot and shoe industry, 1930-1880, in Masters to Managers: Historical and Comparative Perspectives on American Employers (S.M. Jacoby, ed.), Columbia University Press, New York.

disadvantaged, will require changes to the organization of work and the institutions in which it is embedded. One example may be to stimulate the formation of organizations or occupational associations, similar to the Freelancers Union, that provide contingent workers with avenues for acquiring portable health insurance and retirement savings programs. Regulations could also be shaped to better enable contingent workers who have been traditionally categorized as independent contractors to access benefits and protections through their employer, ensuring protection of their rights under U.S. employment law. There is already mounting political pressure to both use existing regulations and introduce new ones to prevent the rise of contingent work in certain areas (such as the taxicab market). Much of this pressure might be motivated by narrow-interest politics (e.g., protecting rents for certain workers or business owners), which is certainly no substitute for a holistic rethinking of regulations, given the extent of contingent work today.

There are limited data on the nature and extent of contingent work in the U.S. workforce and how IT is affecting its role in the labor market. A clear and longitudinally valid system for characterizing contingent jobs could help to clarify the economic and social effects of different forms of contingent work and how they are changing. It is worth noting that 2005 was the last year that the Bureau of Labor Statistics collected data on the contingent workforce, although plans for another survey are under way and an independent, standalone version of a similar survey was conducted through the RAND Corporation, as contracted by economists Alan Krueger and Larry Katz.29 Data collection is discussed in more detail in Chapter 6.

DYNAMISM AND FLEXIBILITY OF THE U.S. WORKFORCE

A hallmark of the U.S. economy has long been its high business dynamism (its pace of business formation, expansion, contraction, and exit) and labor market fluidity (its pace of the flows of workers between jobs and firms). Dynamism and fluidity are inherently linked because much of the flow of workers across jobs stems from business expansion, contraction, entry, and exit. However, “churning” of workers (fluidity in excess of that due to business dynamism) has increased as workers (especially young workers) engage in job hopping (frequent transitions

___________________

29 L.F. Katz and A.B. Krueger, 2016, “The Rise and Nature of Alternative Work Arrangements in the United States 1995-2015,” Princeton University and NBER, https://krueger.princeton.edu/sites/default/files/akrueger/files/katz_krueger_cws_-_march_29_20165.pdf.

between jobs) to develop their careers and find the best match for their skills and interests.

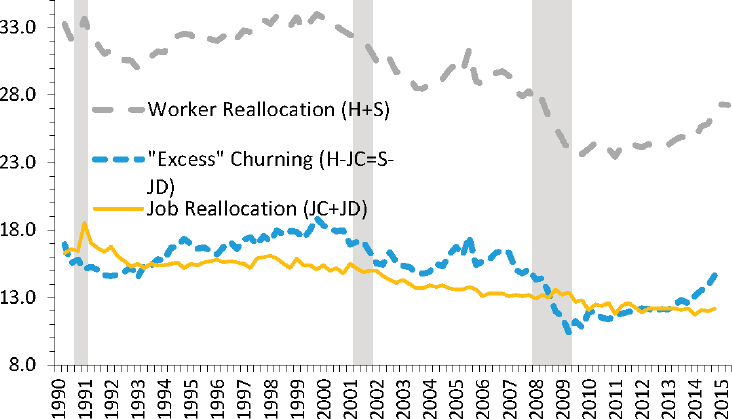

Historically, the United States has exhibited strong indicators of dynamism, such as a high pace of job and worker reallocation, job hopping, and geographic mobility. This dynamism has enabled the United States to reallocate resources from less productive to more productive businesses with less time and resource costs than other countries (e.g., without high rates or long durations of unemployment). In the last several decades—and especially since 2000—there has been a decline in several indicators of business dynamism and labor market fluidity. As illustrated in Figure 4.1, the pace of job reallocation (the sum of jobs created and destroyed) has declined, and the pace of worker reallocation (the sum of hires and separations) has declined. This is linked to declines in related measures of labor market fluidity. The pace of job hopping, as measured by the fraction of workers switching directly from one job to another, often called

job-to-job flows, has also declined.30 Job-to-job flows have historically been critical for helping young workers build their human capital and their careers. Workers moving directly from job to job in the United States have largely reflected workers moving up the job ladder, defined in terms of firm wages or productivity. Geographic mobility has also declined, although the U.S. labor market is still generally more flexible than those of other developed countries and thus perhaps better positioned to adapt to technological change.31,32

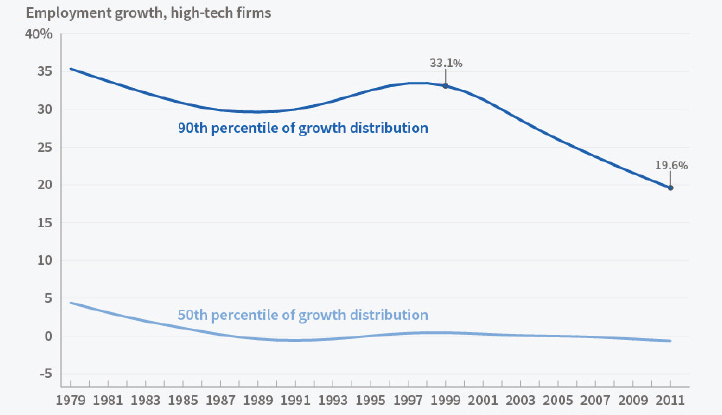

There are also fewer new companies in the United States. New companies accounted for about 13 percent of all firms in the late 1980s, but only 8 percent in 2007.33 This has direct implications for the adoption and diffusion of new technologies. Since the year 2000, there has been a similar decline in the number of high-growth start-ups and the amount of employment in these firms, as indicated in Figure 4.2.34

There are many open questions about this phenomenon, and it is difficult to draw inferences about these changes. There is no doubt, however, that the decline in dynamism and start-ups are connected to the decline in labor market fluidity. Young firms exhibit an especially high pace of job reallocation, with some firms rapidly expanding while others contract and exit. This implies a high pace of hires and separations at such firms. The implication is that a decline in start-ups translates into a decline in labor market fluidity. Moreover, dynamism and flexibility have arguably facilitated the ability of the United States to adapt to past periods of rapid technological change. Davis and Haltiwanger provide evidence that the decline in labor market fluidity has had an adverse effect on labor force participation, especially among the young and less educated. These are the most vulnerable groups that may be left behind by technology.35

___________________

30 S.J. Davis and J. Haltiwanger, 2014, “Labor Market Fluidity and Economic Performance,” No. w20479, National Bureau of Economic Research. See also Figure 3-19, “Economic Report of the President,” Council of the Economic Advisers, February 2015, https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/docs/cea_2015_erp_complete.pdf.

31The Economist, 2014, “America’s Famously Flexible Labour Market Is Becoming Less So,” August 28, http://www.economist.com/news/finance-and-economics/21614159-americasfamously-flexible-labour-market-becoming-less-so-fluid-dynamics.

32 R.J. Gordon, 2003, “Exploding Productivity Growth: Context, Causes, and Implications,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, No. 2, Brookings Institution, Washington, D.C.

33 R.A. Decker, J. Haltiwanger, R.S. Jarmin, and J. Miranda, 2015, “Where Has All the Skewness Gone? The Decline in High-Growth (Young) Firms in the U.S,” NBER Working Paper No. 21776, last revised January 8, 2016, http://www.nber.org/papers/w21776.

34 Ibid.

35 S.J. Davis and J. Haltiwanger, 2014, “Labor Market Fluidity and Economic Performance,” University of Chicago and NBER, and University of Maryland and NBER, http://faculty.chicagobooth.edu/steven.davis/pdf/LaborFluidityandEconomicPerformance26November2014.pdf.

These findings seem inconsistent with an increase in contingent workers engaged in short-duration gig jobs. As noted above, there is currently not much evidence that gig economy jobs are quantitatively significant in the overall U.S. economy.36 However, the statistics reported in this section reflect employers with at least one paid employee (and the employers themselves), which excludes many gig workers who are more likely to be independent contractors.

Changes in the Prevalence of Start-up Companies

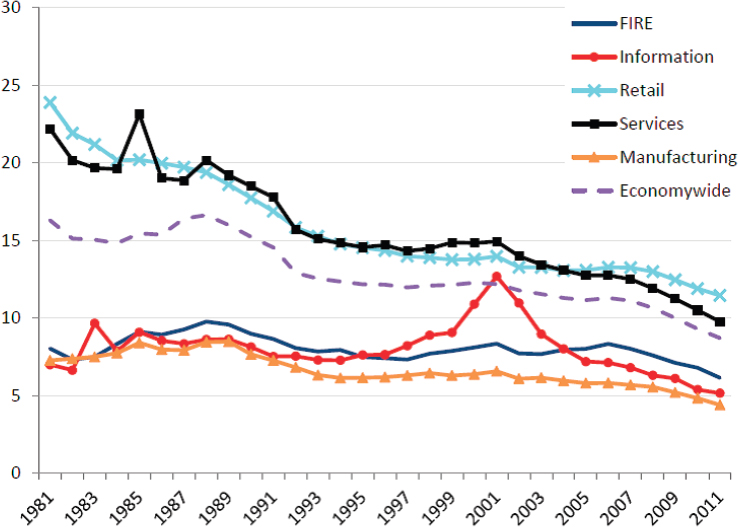

Underlying part of this decline is a decline in dynamism in the pace of start-ups and high-growth young firms. Before 2000, this phenomenon was concentrated in certain sectors, such as retail trade, where there has been a shift in the business model toward large national chains (see Figure 4.3 for the fraction of employment over time attributed to jobs at young firms in specific sectors). Evidence suggests that such companies

___________________

36 Katz and Krueger, 2016, “The Rise and Nature of Alternative Work Arrangements in the United States 1995-2015.”

are both more productive and stable than the small, single-unit establishment firms that have been displaced. This highlights the fact that a high pace of start-ups and business dynamism is not an economic objective in and of itself. Instead, the optimal pace of start-ups and reallocation should balance productivity and economic growth benefits with the costs of this reallocation. The latter can be high for certain firms and individuals who experience the most change. As argued above, in retail trade this change in the business model has arguably had some positive effects where the decline in startups and dynamism is associated with improved productivity in this sector. Evidence suggests that this change has been facilitated by IT, which has enabled large multinational retail firms to develop efficient distribution networks and supply chains globally. Of potentially greater concern is the decline in high-tech start-ups and in

young business activity in the United States since 2000,37 as illustrated in Figure 4.3. Prior to 2000, high-growth firms in high tech (those with an employment-weighted growth rate in the 90th percentile) had annual net employment growth rates more than 30 percent higher than the median firms; these firms were predominantly young. Since 2000, high-growth firms declined, and the 90-50 differential dropped to less than 20 percent. This is the same period in which there has been a decline in the growth of productivity in the high-tech sectors.38,39

These trends, especially in the high-tech sector, raise a variety of questions. One interpretation is that changes in IT and automation have favored larger organizations. Network externalities imply common adoption of software and hardware platforms. Consistent with this, it may be that as the information and technology revolution has matured, the objective of start-ups developing new innovations has changed from internal high growth to being acquired by dominant firms in their industry. These patterns do not imply that high-growth start-ups in high tech are no longer playing an important role. It is evident that there are rapid increases in start-ups in the sharing economy; however, the business model of such start-ups is to grow via partnerships rather than by increasing numbers of paid employees. It is also possible that high-tech companies with potential for high growth are increasingly basing their production activities worldwide and thus not increasing their domestic employment. Overall, the organizational structure and incentives of start-ups may underlie these changes, which are also driven by changes in IT.

CHANGING WORKER DEMOGRAPHICS AND JOB SATISFACTION

While considering the role of information technologies in the changing nature of work, it is important to keep concurrent social changes in mind. The demographics of the U.S. population are undergoing a major shift: it has been projected that there will be no ethnic or racial majority in the United States by 2050. The demographics of today’s employees are also changing. Women make up nearly half of the labor force today and,

___________________

37 High Tech is defined using the approach of Daniel E. Hecker (see D.E. Hecker, 2005, High-technology employment: NAICS-based update, Monthly Labor Review, July, pp. 57-72). It is based on the most STEM intensive 4-digit NAICS industries. It includes all of the sectors normally considered part of the ICT industries (in the information, service and manufacturing industries).

38 J.G. Fernald, 2015, Productivity and potential output before, during, and after the Great Recession, in NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2014, Volume 29, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Ill.

39 Decker et al., 2015, “Where Has All The Skewness Gone?”

as of June 2012, 36 percent of workers were not Caucasian. The millennial generation, which recently surpassed the baby boomers as the largest generation,40 is also the most racially and ethnically diverse. As more millennials enter the workforce and older individuals retire, the racial and ethnic diversity of the workforce is expected to continue to increase.41,42

Even as the diversity of the workforce is increasing, significant inequalities exist. Social, economic, racial, and political backgrounds are highly correlated with academic achievement, economic opportunity, income, and social mobility. For example, the wealth gap between racial and ethnic groups has widened since the Great Recession; the Pew Research Center estimated that the 2014 median net worth of white households was 13 times that of African American households (up from a factor of 10 in 2007, and a factor of 6 from 1998-2001) and 10 times that of Hispanic households (up slightly from a factor of 8 in 2007).43

While an increasing number of African Americans and Hispanics have been attending postsecondary institutions, and representation of these groups at top-ranked colleges has grown slightly since the 1990s, significant disparities remain. Of the net new enrollments from 1995 to 2009, the majority (more than 80 percent) of white students went to selective colleges, while the majority (more than 70 percent) of African American and Hispanic students attended open-admissions 2- and 4-year colleges.44,45,46

In the long term, disparities in opportunity and achievement, and racial and ethnic isolation by school selectivity, will keep some workers at a disadvantage in meeting current and changing workforce requirements. In response, some organizations are increasing investments in

___________________

40 R. Fry, 2016, “Millennials overtake Baby Boomers as America’s largest generation,” Pew Research Center, http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/04/25/millennialsovertake-baby-boomers/.

41 C. Burns, K. Barton, and S. Kerby, 2012, “State of Diversity in Today’s Workforce: As Our Nation Becomes More Diverse So Too Does Our Workforce,” Center for American Progress, https://cdn.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/issues/2012/07/pdf/diversity_brief.pdf.

42 A. Mitchell, 2013, “The Rise of the Millennial Workforce,” Wired, http://www.wired.com/insights/2013/08/the-rise-of-the-millennial-workforce/.

43 R. Kochhar and R. Fry, 2014,”Wealth Inequality Has Widened Along Racial, Ethnic Lines Since End of Great Recession,” Pew Research Center, http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/12/12/racial-wealth-gaps-great-recession/.

44 Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, Analysis of Current Population Survey, March Supplement, 1980.

45 Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, Projection of Labor Force Makeup by Race/Ethnicity, 2014.

46 A.P. Carnevale and J. Strohl, 2013, “Separate and Unequal: How Higher Education Reinforces the Intergenerational Reproduction of White Racial Privilege,” Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, Washington, D.C.

diversity training programs, described as “a distinct set of programs aimed at facilitating positive inter-group interactions, reducing prejudice and discrimination and enhancing the skills, knowledge and motivation of people.”47,48

The stagnation of median wages (discussed in Chapter 3) and the contingent nature of parts of the current workforce may be correlated with the continued decline in reported employee job satisfaction. According to one study, job satisfaction was at 61.1 percent in 1983, and this number has steadily decreased over time.49 A recent Conference Board report50 indicated that a majority of Americans (52.3 percent) are not satisfied with their job, and satisfaction across almost all job domains has decreased since 2011. The decreases were most pronounced in the areas of job security, health coverage, and sick leave policies. In spite of increased hiring, only 46.6 percent of employees indicated feeling satisfied with their job security (which is down from 48.5 percent before the Great Recession). Another potential source of decreased job satisfaction may be that employers are offering fewer benefits.51 Indeed, 63 percent of workers identified this as very important to their job satisfaction.52

ORGANIZATIONS AND INSTITUTIONS

IT not only affects the nature of work and the labor market, but it also reshapes organizations by changing internal and geographical divisions of labor. Adoption of IT alone has not been sufficient to guarantee gains in productivity; new technologies must be accompanied by changes in the organizational structure of firms, including human resource practices.53,54

In addition, as technologies refashion aspects of organizations, they

___________________

47 K. Bezrukova, K.A. Jehn, and C.S. Spell, 2012, Reviewing diversity training: Where we have been and where we should go, Academy of Management Learning and Education 11(2):207-227.

48 H. Alhejji, T. Garavan, R. Carbery, F. O’Brien, and D. McGuire, 2015, Diversity training programme outcomes: A systematic review, Human Resource Development Quarterly 27(1):95-149.

49 L. Weber, 2014, “U.S. Workers Can’t Get No (Job) Satisfaction,” Wall Street Journal blog, June 18, http://blogs.wsj.com/atwork/2014/06/18/u-s-workers-cant-get-no-job-satisfaction/.

50 C. Mitchell, R.L. Ray, and B. van Ark, 2014, “CEO Challenge 2014,” The Conference Board, https://www.conference-board.org/retrievefile.cfm?filename=TCB_R-1537-14-RR1.pdf&type=subsite.

51 L. Weber, 2014, “U.S. Workers Can’t Get No (Job) Satisfaction,” Wall Street Journal blog, June 18, http://blogs.wsj.com/atwork/2014/06/18/u-s-workers-cant-get-no-job-satisfaction/.

52 Society for Human Resource Management, 2015.

53 E. Brynjolfsson and L.M. Hitt, Beyond computation: Information technology, organizational transformation and business performance, Journal of Economic Perspectives 14(4):24-48.

54 N. Bloom, B. Eifert, A. Mahajan, D. McKenzie, and J. Roberts, 2013, Does management matter? Evidence from India, Quarterly Journal of Economics 128(1):1-51.

may also occasion new organizational forms and arrangements. Because policies and macro-institutional frameworks are becoming increasingly inadequate for this bewildering array of changes, new macro-institutional responses may be necessary. Each of these topics is addressed in turn.

Vertical Integration, Disintegration, and Geographical Proximity

Many companies took advantage of the range of technological opportunities of the late 1800s to create vertically integrated firms, an organizational form that combined many stages of the production process.55 When the transaction and communication costs of vertically integrating different stages of production appeared prohibitive, a firm and its suppliers developed close long-term relationships, often aided by geographic proximity. The auto industry, surrounded by its various suppliers within the Detroit area, is a prime example of this structure. Over time, integrated functional organizations developed a distinct system of employment relations, distinguished by long job tenure, internal promotion structures, and an acceptance of trade and industrial unions as the main vehicle for worker voice and protection.56 This system of organizing began to change significantly in the late 1970s. Although the major recession of that decade played a role in the system’s demise, technological change also enabled companies to move away from this structure. Gradual but transformative improvements in computer and communication technology reduced the need for geographic proximity with suppliers. They also enabled a finer division of labor, parts of which could be easily outsourced. Computerized communication and information technologies allowed firms to offshore many stages of production to parts of the world where they could be performed more cheaply (often because labor was cheaper).

Products such as the iPod, although designed in the United States, are produced by combining more than 450 parts, produced in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, that are assembled in China.57 A global division of labor enabled Apple to take advantage of expertise in making specific components distributed around the world (such as hard drives manufac-

___________________

55 O.E. Williamson, 1975, Markets and Hierarchies, Free Press, New York; A. Chandler, 1977, The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass.

56 M. Piore and C. Sabel,1984, The Second Industrial Divide, Basic Books, New York; T.A. Kochan, H.C. Katz, and R. B. McKersie, 1986, The Transformation of American Industrial Relations, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, N.Y.

57 K.L. Kraemer, G. Linden, J. Dedrick, 2011, “Capturing Value in Global Networks: Apple’s iPad and iPhone,” University of California, Irvine, http://pcic.merage.uci.edu/papers/2011/value_ipad_iphone.pdf; H. Varian, 2007, “An iPod Has Global Value. Ask the (Many) Countries That Make It,” New York Times, June 28, Section 3C.

tured by Toshiba in Japan) and of the cheaper cost of assembly in China than in the United States. Even for products that are produced domestically, geographical proximity plays less of a role than it did in the 19th and 20th centuries. As a result of these changes, organizational theories have begun to speak of network forms of organizing as an alternative to markets and hierarchies.58

Distributed and Interdisciplinary Teaming and Networks

Geographically distributed teams, whose members not only span a firm’s domestic locations but often include members or collaborators from other countries and continents, have increased.59 Historically, collaboration and communication among team members has required co-presence in time and space. IT can enable teamwork in the absence of co-presence and has enabled the rise of distributed teams. On the one hand, distributed teaming enables firms to take advantage of pockets of expertise regardless of where they exist and to have someone available to work on a project literally 24 hours a day. Such teams are composed of members that primarily, and in some cases only, interact via technological means.60,61,62 Such teams are generally designed to allow for optimal team composition without the burden of travel expenses and allow workers to work more efficiently and hone skills by working on a larger variety of complex tasks; it also enables a seamless transition from one project to another.

However, the rise of distributed teams has created numerous organizational challenges, ranging from communication breakdowns and problems in the production process to cultural misunderstandings, incongruent work ethics, and the inability of team members to identify accurately

___________________

58 W.W. Powell, 1990, Neither market nor hierarchy: Network forms of organization, pp. 295-335 in Research in Organizational Behavior (B.M. Staw and L.L. Cummings, eds.), JAI Press, Greenwich, Conn.

59 J.P. MacDuffie, 2007, 12 HRM and distributed work: Managing people across distances, Academy of Management Annals 1(1):549-615.

60 W.F. Cascio, 1998, The future world of work: Implications for human resource costing and accounting, Journal of Human Resource Costing and Accounting 3(2):9-19.

61Business Week, 1997, “Power gizmos to power business,” November 24, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/1997-11-23/power-gizmos-to-power-business.

62 S.M. Fiore, E. Salas, H.M. Cuevas, and C.A. Bowers, 2003, Distributed coordination space: Toward a theory of distributed team process and performance, Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science 4(3-4): 340-364.

who is on their team.63,64,65 It may be necessary for organizations to create effective norms to help mitigate challenges associated with virtual tools (e.g., reduced understanding as a consequence of being unable to perceive the nonverbal cues and gestures afforded via face-to-face communication).

Similarly, the use of interdisciplinary teams (IDTs) has also gained popularity, namely in the area of health, but its usage is beginning to take root in corporate and science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields as well.66 IDTs are comprised of experts within a given field that collaborate and coordinate with each other to complete complex tasks.67 According to the American Geriatrics Society, IDTs allow medical professionals to address a patient’s overall needs, which can remain unmet in a noncollaborative setting.68 Each team member brings unique strengths to the team as a consequence of possessing different expertise. Such teams are able to collectively provide more to patients.

However, as the prevalence of IDTs grows, organizations will have to increasingly contend with the challenges such teams face; it has been suggested that employees from different disciplines may differ in regard to training, professional values, understanding of team roles, communication skills, vocabulary, and approaches to problem solving.69 As a consequence of these differences, team members from different disciplines may ultimately lack common understanding. These problems can negatively affect team performance. For example, teamwork failures in interdisciplinary health-care teams have been linked to reduced quality of patient care. Conversely, enhanced teamwork in such teams has been

___________________

63 D.E. Bailey, P.M. Leonardi, and S.R. Barley, 2012, The lure of the virtual, Organization Science 23:1485-1504; P.J. Hinds and S. Kiesler, 2002, Distributed Work, MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass.; M. Mortensen and P. Hinds, 2001, Conflict and shared identity in geographically distributed teams, International Journal of Conflict Management 12(3):212-238; C.D. Cramton and P.J. Hinds, 2005, Subgroup dynamics in internationally distributed teams: Ethnocentrism or cross-national learning, Research in Organizational Behavior 26:231-263.

64 C.D. Cramton, 2001, The mutual knowledge problem and its consequences in geographically dispersed teams, Organization Science 12(3):346-371.

65 P. Kanawattanachai and Y. Yoo, 2007, The impact of knowledge coordination on virtual team performance over time, MIS Quarterly 31(4):783-808.

66 T.A. Slocum, R. Detrich, S.M. Wilczynski, T.D. Spencer, T. Lewis, and K. Wolfe, 2014, The evidence-based practice of applied behavior analysis, The Behavior Analyst 37(1):41-56.

67 S.A. Nancarrow, A. Booth, S. Ariss, T. Smith, P. Enderby, and A. Roots, 2013, Ten principles of good interdisciplinary team work, Human Resource Health 11(19), doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-11-19.

68 C.A. Orchard, V. Curran, and S. Kabene, 2005, Creating a culture for interdisciplinary collaborative professional practices, Medical Education Online 10(11), http://www.med-ed-online.net/index.php/meo/article/viewFile/4387/4569.

69 P. Hall, 2005, Interprofessional teamwork: Professional cultures as barriers, Journal of Interprofessional Care 19(Supplement 1):188-196.

linked to increased patient care and patient safety.70,71 Evidence suggests that team training is one method to improve effectiveness in interdisciplinary teams, allowing team members to work effectively despite differing in many respects.72 Thus, if the trend of using IDTs continues, organizations may need to increasingly invest in training to ensure effective team performance.

Changing Employment Relationships

In addition to the changes described above, advances in IT have also helped unravel the foundation of traditional employment relationships.

Beginning with Henry Ford’s car factories, during the 20th century many firms made a concerted effort to pay relatively high wages to their employees as a way of creating relationships of mutual loyalty. In particular, Henry Ford was worried about high rates of absenteeism. High wages would reduce turnover, motivate workers to work harder, and create goodwill between employers and employees.73 Recent advances in the ability of firms to monitor their employees effectively through computer technologies and to outsource activities that can be performed more cheaply elsewhere may have reduced the need to pay attractive wages, thus reducing the cost of labor for certain types of firms and, hence, reducing the “quasi-rents” that workers enjoy from the employment relationship. The role of computerization in reducing wages has, of course, been amplified by attempts to dismantle or avoid unions74 and by Wall Street’s willingness to reward firms for finding ways to turn labor into a variable

___________________

70 E. J. Dunn, P. D. Mills, J. Neily, M. D. Crittenden, A. L. Carmack, and J. P. Bagian, 2007, Medical team training: Applying crew resource management in the Veterans Health Administration, Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety 33(6):317-325.

71 T. Manser, 2009, Teamwork and patient safety in dynamic domains of healthcare: A review of the literature, Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica 53(2):143-151.

72 Ibid.

73 C. Shapiro and J.E. Stiglitz, 1984, Equilibrium unemployment as a worker discipline device, American Economic Review 74(3):433-444; G.A. Akerlof, 1984, Gift exchange and efficiency-wage theory: Four views, American Economic Review 74(2):79-83; T.F. Bewley, 1995, A depressed labor market as explained by participants, American Economic Review 85(2):250-254.

74 T.A. Kochan, H.C. Katz, and R.B. McKersie, 1986, The Transformation of American Industrial Relations, Basic Books, New York; P. Osterman, T.A. Kochan, R.M. Locke, and M.J. Piore, 2001, Working in America: Blueprint for the New Labor Market, MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass.; A.L. Kalleberg, B.F. Reskin, and K. Hudson, 2000, Bad jobs in America: Standard and nonstandard employment relations and job quality in the United States, American Sociological Review 65(2):256-279.

cost, to some degree by breaching implicit, long-term agreements with workers.75

Furthermore, while there is much attention to the effects of IT on start-ups and on large, but relatively new, technology companies, traditional companies are also in the midst of a transformation. Walmart has been a leader in adopting supply-chain management systems, radiofrequency identification tags, and other technologies that enable it to manage its operations more efficiently, better understand customer demand, reduce costs, and substantially increase productivity. Many of its biggest successes came in the 1980s and 1990s,76 but it is still an important force in retailing and the economy more broadly. Walmart employs far more people than Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft combined. This suggests that a large part of the impact of IT on workers is occurring through traditional firms. As noted by Zeynep Ton, there is wide variation in pay and working conditions in industries such as retail, hospitality, health care, and other big users of labor.77 Understanding how IT is being used as part of a business strategy in firms that are providing stable jobs would be helpful in identifying private and public policy options for improving workforce conditions.

Consequences of Transformations of Traditional Organizations

The transformation of traditional organizations may have numerous and far-reaching social consequences. Three are highlighted.

First, if organizations are now providing less secure and shorter-term employment, workers may not have the financial means to withstand more lengthy spells of unemployment or underemployment. For workers to flourish in more fluid labor markets, basic skills will probably be even more important than they are today. New education policies may be needed that not only strengthen existing educational institutions (so that high schools become much better at providing basic skills as well as vocational skills) but also promote new ways of encouraging people to acquire general, portable skills. Although making college more affordable

___________________

75 S.R. Barley and G. Kunda, 2004, Gurus, Hired Guns and Warm Bodies: Itinerant Experts in a Knowledge Economy, Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

76 For instance, a report by McKinsey Global institute estimated at that as much as a quarter of the productivity revival in the late 1990s could be directly or indirectly attributed to Walmart’s effects on the retailing sector and its supply chain. See, for example, B. Lewis, A. Augerau, M. Cho, B. Johnson, B. Neiman, G. Olazabal, M. Sandler, et al., 2001, “US Productivity Growth, 1995-2000,” McKinsey Global Institute, http://www.mckinsey.com/global-themes/americas/us-productivity-growth-1995-2000.

77 Z. Ton, 2014, The Good Jobs Strategy: How the Smartest Companies Invest in Employees to Lower Costs and Boost Profits, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston, Mass.

to more people is a reasonable first step, it is also worth reconsidering the type of skills that young people require aside from purely technical skills, which may have a short shelf life. Simply recommending that more young people attend college may not be sufficient.78

Second, as traditional employment relationships decrease, it is unclear how workers will secure the benefits, security, and voice that organizations provided during the mid-20th century. The result of the New Deal was a series of laws that tied permanent employment to having good health-care benefits and pension funds. As long-term employment becomes less common, new ways of providing for health care and pensions for all workers need to be considered that transcend their relationships with particular employers. For example, one option would be to institute portable pension plans administered by membership organizations dedicated to the well-being of their members.

Unions, as already noted, played an important role in the era of bureaucratically organized firms. They not only negotiated higher wages but also better working conditions, which then spread to other industries either through pattern bargaining or because firms wished to avoid being unionized. Unions also provided workers with voice. An oft-used framework for thinking about workplace relations emphasizes the balance between exit, voice, and loyalty.79 Workers use their voice to communicate their knowledge and demands when they have high attachment to their organization; alternatively, they may use their exit option when opportunities for voice are not available. This framework, although conceptually powerful, has become less applicable today: more workers choose to or are forced to exit despite their willingness to stay. To the degree that exit becomes more attractive than voice, organizations lose the communication channels that traditional unions were able to provide. This may imply the need for new organizational pathways for ensuring that workers continue to have a voice, both about their working conditions as well as broader societal issues.

In industries where unionization is in significant decline, the best a union can do is negotiate a better deal for their remaining members, often at the expense of other workers. New organizational pathways for workers to have an effective voice in the face of increasingly fluid work conditions are becoming even more important.

___________________

78 See D. Acemoglu and D. Autor, 2011, Skills, tasks, and technologies: Implications for employment and earnings, pp. 1043-1171 in Handbook of Labor Economics, Volume 4b, Elsevier B.V., Amsterdam, The Netherlands; and P. Beaudry, D.A. Green, and B.M. Sand, 2014, “The Great Reversal in the Demand for Skill and Cognitive Tasks,” National Bureau of Economic Research, doi: 10.3386/w18901.

79 A.O. Hirschman, 1970, Exit, Voice, and Loyalty, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass.

Guaranteeing a voice to workers in a more flexible and uncertain economy may require entirely new organizational forms. There are two alternatives of note that have been used in other countries. The first is the German-style work council, which is as focused on communication and coordination as it is on negotiation. Although these councils have flourished in the context of traditional organizations, a more flexible version could play a role in the age of more fluid organizations. The second is the Scandinavian-style industry or occupational union, which represents workers across establishments, thereby enhancing resilience in the face of very high mobility across firms. Once again, the traditional form of these trade unions is probably inadequate for the modern organization (because the industry or occupation may not be the right level of aggregation), but it may provide a stepping stone for a more appropriately tailored pathway of communication for the modern age.

Third, more attention could be given to the “macro-institutions” that determine national or state-level frameworks and policies. The need to rethink these macro-institutions stems from two distinct but related considerations. First, many of the organizational issues that require fundamental modification cannot be done in a decentralized fashion. Making health insurance and pension benefits more portable within the economy is not something that individual firms can achieve. Nor can local communities independently provide a modern social safety net; this requires appropriate tax and redistribution policies from state and federal governments. One such policy that has been considered in the United States in the past (and is currently being tested and studied in the Netherlands) is a minimum guaranteed income for all; this has been discussed as a potential safety net against technological or other widespread unemployment.80 Even with new organizational forms for worker representation, it would likely be necessary for the federal government to be involved by, for example, rewriting labor laws to enable such a transformation.

The potential for many new technological developments to lead to inequality, at least in the medium run, and the potential of some of these technologies, through automation, to reduce employment opportunities for major segments of the population, make the need for responsive national policies more important than ever, in the committee’s judgment. At the same time, many feel that today’s political institutions are less responsive and less accountable to the welfare of the whole. Part of this may be unrelated to technology and may result from a change in the distribution of power between different segments of society (or it may be

___________________

80 In particular, the experiment is studying the impact of an annual income equivalent to roughly US$13,000 (T.B. Hamilton, 2016, “The Netherlands’ upcoming money-for-nothing experiment,” The Atlantic, June 21).

driven by ideological factors that have made major political parties in the United States less responsive). However, even these developments may be a result of technological change. Some technological transformations may have increased the political voice and power of some segments of society over others. Some writers contend, for example, that Wall Street’s rise to political power is partially rooted in technological capabilities that allow traders and hedge fund managers to accumulate wealth at a faster rate than other groups.81

No matter what its causes, the debate over increasing the responsiveness and accountability of the political process is an important part of the broader debate about how to reshape organizations and institutions to be more congruent with social needs, including vibrant dialogue on how to make better use of new technologies. Some of this has already taken place in other countries, for example, by enabling greater voter participation and direct input into politics and creating greater transparency.

THE ROLE OF WORK IN OUR LIVES

Work occupies a great deal of people’s time and attention and has played a central role in shaping a sense of worth and identity. More importantly, in the context of this report, technological developments have at least indirectly shaped how people experience the place of work in their lives. For example, prior to the development of the clock and eventually electrical lighting, work time and personal time were largely synchronized to daily and seasonal cycles. Following the spread of these technologies, work hours became partially decoupled from nature’s cycles. Stints of work grew increasingly longer until, after decades of union agitation, Congress eventually passed the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which limited the standard work week to a maximum of 40 hours and mandated premium pay for additional hours.82 The 8-hour day, coupled with the routine and repetitive nature of many jobs (such as typing, data entry, and operating machine tools on assembly lines), contributed to the separation of work and leisure typical of many workers of the 1940s through the 1970s. After working an 8-hour shift, workers returned to their homes exhausted and fatigued, but the evenings were theirs to use

___________________

81 N. Fligstein, 1993, The Transformation of Corporate Control, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass.; M. Lewis, 2014, Flash Boys, Norton, New York.

82 J. Grossman, “Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938: Maximum Struggle for a Minimum Wage,” United States Department of Labor, https://www.dol.gov/oasam/programs/history/flsa1938.htm#1.

as they wished, and weekends became times for leisure and for dreaming of vacations and retirement.83

Computerized information and communication technologies are similarly affecting workers’ lives on at least four fronts: (1) the gradual erasure of the boundaries between work and other aspects of their lives, particularly the family; (2) the use of computer systems to monitor workers’ performance, with potential intrusion on the workers’ privacy; (3) the potential to displace the physical workplace as a primary locus of social identity and sociality; and (4) shifts in the labor market that could help confound gender stereotypes.

Because of IT (including e-mail, teleconferencing systems, and the use of the Web as a work tool), it is now much easier for work to spill over into workers’ family life in any field that employs them. Although these developments are often heralded as a form of freedom that can allow individuals to work from anywhere at any time, thereby maximizing a worker’s temporal freedom and flexibility, there is considerable evidence that such flexibility has come at the cost of blurring the boundaries between work and other aspects of life. Over the last several decades, researchers have accumulated a large body of research on work-family balance, and most of the evidence points toward a single conclusion: work has begun to infiltrate times and places it previously did not (and vice versa), potentially leading to an increase in work-family conflict.84 Although the rise of dual-career families has contributed strongly to these developments, the use of IT is also strongly implicated.85 When workers are linked on distributed teams, the ability to hold meetings and send

___________________

83 For excellent account of the role of work and leisure among blue collar factory workers of the 1940s and 1950s, see C.R. Walker and W.H. Guest, 1952, The Man on the Assembly Line, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass.

84 J.B. Schor, 1993, The Overworked American: The Unexpected Decline of Leisure, Basic Books, New York; J.A. Jacobs and K. Gerson, 2004, The Time Divide: Work, Family and Gender Inequality, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass.; P. Moen, 2003, It’s About Time: Couples and Careers, ILR Press, Ithaca, N.Y.; L. Alvarez, 2005, “Got 2 Extra Hours for Your E-Mail?,” New York Times, November 10, http://www.nytimes.com/2005/11/10/fashion/got-2-extrahours-for-your-email.html?_r=0; W.C. Murray and A. Rostis, 2007, Who’s running the machine? A theoretical exploration of work, stress and burnout of technologically tethered workers, Journal of Individual Employment Rights 12:349-263.

85 J.A. Jacobs and K. Gerson, 2004, The Time Divide: Work, Family and Gender Inequality, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass.; L.A. Dabbish and R.E. Kraut, 2006, “Email Overload at Work: An Analysis of Factors Associated With Email Strain,” pp. 431-440 in Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, ACM Press, New York; N. Chesley, 2005, Blurring boundaries? Linking technology use, spillover, individual distress, and family satisfaction, Journal of Marriage and Family 67:1237-1248; K. Renaud, J. Ramsay, and M. Hair, 2006, ‘You’ve got e-mail!’ . . . . Shall I deal with it now? Electronic mail from the recipient’s perspective, International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction 21(3):313-332.

work-related e-mails across time zones extends people’s work into the mornings before they go to the office and into the evenings after they come home.86 The ability to engage in work-related communications during lunches, dinners, and even social events leads people to feel obligated to do so and infuses settings that were previously primarily social with work-related content.87 At the same time, technology provides increased opportunities for leisure activities at work, from mobile games and online shopping to social media and personal communications. There is evidence that the blurring of work and other aspects of life are especially common among people in managerial, professional, and technical occupations.88 Given the strength of the research on this phenomenon and the evolving functionality of smartphones, there is no reason to believe this phenomenon will disappear. In short, information and communication technologies appear to be eliminating the boundary between work and the other arenas of life that were forged by the combination of technologies, institutions, and social understandings that marked the mid-20th century.

Over the last several decades, employers have increasingly used information technologies to monitor the productivity and diligence of white-collar workers, even as the shift from physical to mental tasks reduced the direct visibility of many types of work. The use of data collected by computers and information technologies enables employers to impose and enforce productivity objectives and to reward and punish workers who do or do not achieve those objectives. Although this kind of monitoring is widespread in call centers, for example, where workers are expected to handle a set number of calls per unit time and to spend a set number of minutes per call, monitoring also extends to workers of all types, including professionals.89 Computerized monitoring extends and intensifies the kind of performance monitoring analogous to the time and motion studies typically conducted by industrial engineers in factory set-

___________________

86 S.R Barley, D.M. Meyerson, and S. Grodal, 2011, Email as a source and symbol of stress, Organization Science 22:262-285.

87 M. Mazmanian, J. Yates, and W.J. Orlikowski, 2006, “Ubiquitous Email: Individual Experiences and Organizational Consequences of Blackberry Use,” in Proceedings of the 65th Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management, Academy of Management, Atlanta, Ga.

88 S. Schieman and P. Glavin, 2008, Trouble at the border?: Gender, flexibility at work, and the work-home interface, Social Problems 55(4):590-611; S. Schieman and P. Glavin, 2011, Education and work-family conflict: Explanations, contingencies and mental health consequences, Social Forces 89(4):1341-1362.

89 R. Batt and L. Moynihan, 2002, The viability of alternative call center production models, Human Resource Management Journal 12(4):14-34; R. Batt, V. Doellgast, and H. Kwon, 2006, Service management and employment systems in U.S. and Indian call centers, in Brookings Trade Forum 2005: Offshoring White-collar Work—The Issues and Implications (S. Collins and L. Brainard, eds.), Brookings Institution, Washington, D.C.

tings to white-collar and professional work. Monitoring has been poorly received in the past by blue-collar employees; some attempts to put such monitoring systems into place led to strikes, for instance the 1911 strike at the Watertown Arsenal in response to Frederick Taylor’s attempt to introduce time and motion studies.90 It is not clear that contemporary workers are any more willing to accept computerized monitoring, assuming that they are aware it is happening, but they are less likely to possess forums for collective action.

For many, the workplace acts as a site for social engagement, both positive and negative, and serves as a key interface between people’s working and personal lives. Indeed, out of social interactions at the workplace and the work that people actually perform, they construct significant components of their identities and self-worth. Communication technologies shape many aspects of when, where, and how social interactions occur and the tenor of their experience. If work becomes less centered on a specific geographic locality, this will fundamentally transform the nature of the social interactions around work. Offshored call-center workers provide an illuminating example. On the one hand, the call center itself may continue to serve as a site of interaction, camaraderie, and competition, while on the other hand, it shifts relations at home when a spouse, sibling, or parent works nights and learns to speak in another accent.91 In short, the offshoring of work via new communications technology can bring to people in other cultures some of the same work-family dynamics found in the United States and discussed above. Other benefits of virtual working include the potential for greater inclusion of people with disabilities and those with children or elder dependents. But not every organization or person will find that this model works for them.

More generally, however, the rise of distributed and contingent project-based work that can be completed from anywhere, including one’s home, while attractive to some workers (especially parents of young children), threatens to undermine the social benefits of being co-present with others in a workplace. Indeed, one of the chief complaints of full-time telecommuters has long been the sense of being isolated and disconnected from one’s colleagues and the fear that being away from the workplace will lead to fewer opportunities for visibility and advancement.92 Despite

___________________

90 H.G.J. Aitken, 1985, Scientific Management in Action: Taylorism at Watertown Arsenal, 1908-1915, Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

91 A. Aneesh, 2006, Virtual Migration: The Programming of Globalization, Duke University Press, Raleigh, N.C.

92 R.E. Kraut, 1989, Telecommuting: The tradeoffs of home work, Journal of Communication 39:19-47; D.E Bailey and N.B. Kurland, 2002, A review of telework research: Findings, new directions, and lessons for the study of modern work, Journal of Organizational Behavior 23(4):383-400; L.A. Perlow, 1997, Finding Time, ILR Press, Ithaca, N.Y.

a great deal of initial fanfare, telecommuting was for decades actually quite rare because managers discouraged it regardless of company policy and, in part, because only certain occupations performed work that was amenable to long absences from the workplace (for instance, software developers and academics). However, working when and where one prefers may become an option for more people with the increased access to work through digital devices and Internet connections, including open-call work platforms, and more opportunities for just-in-time contracts and other temporary work arrangements. Such arrangements preclude the opportunity for social engagement and the sustained work relationships afforded by spatial and organizational co-location.

Under such circumstances, what role will work play in shaping social identities and sense of self? At the moment, very little is known about this topic. There is a long stream of research on careers that suggests that people will construct careers and identities whether or not they have the support of an organization or a recognized occupation.93 But what sort of identities, careers, and selves will people construct in the future, for example, if work becomes a series of gigs done for and with people one never actually meets? Conceivably, under such conditions, people will reemphasize connections with nonwork friends and family. They may also construct unique careers by acquiring additional skills and achievements. But, coupled with the previously discussed precariousness of making a living in contingent labor markets, the committee suspects that these changing employment relations will alter the role work has played in how people assess their sense of value and self-worth.

Gender is yet another aspect of the interplay between technology and work. Most new occupations begin without a gender label, until they are filled by employers and gender correlations emerge.94 To the extent that IT contributes to the creation of new occupations, it provides employment opportunities that are less likely to be associated with gender stereotypes. To the extent that IT and automation may contribute to the displacement of jobs, they are likely to encroach more slowly on many types of care and interactive service work—occupations that have been traditionally populated by women. Indeed, many of the fastest-growing occupations are in labor-intensive service and care occupations, such as child care, nursing, and health technicians. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the health care and social assistance sector is projected to experience the

___________________

93 E.C. Hughes, 1958, Men and Their Work, Free Press, Glencoe, Ill.; S.R. Barley, 1989, Careers, identities, and institutions: The legacy of the Chicago School of Sociology, pp. 41-66 in Handbook of Career Theory (M.B. Arthur, D.T. Hall, and B.S. Lawrence, eds.), Cambridge University Press, New York.

94 For historical examples, see R. Milkman, Gender at Work: The Dynamics of Job Segregation by Sex during World War II, University of Illinois Press, 1987.

largest number of new jobs creation from 2014 to 2024.95 If this trend continues, a key question is whether men will also seek employment in such occupations and find it fulfilling. There are very few historical instances of occupations being transformed from female to male occupations (the converse is more common), although males entering traditionally female fields often ride a “glass escalator” to the upper levels of the field.96 The extent to which gender roles and other work-related aspirations might or might not conflict with the new world of employment that technology is creating, and how such social attitudes might be formed or reformed, is an open question for research. Rethinking attitudes toward these roles could benefit women as well as men, since the persistent gender gap in pay is tightly intertwined with occupational segregation by gender.

EDUCATION AND JOB TRAINING

Technological progress affects the demand for education and training and how education and training are provided.

The common perception that college students are all young adults who enroll in a 4-year college upon completion of high school is no longer correct. For the past 30 years, close to a third of students enrolled in postsecondary institutions have been over the age of 30, and they have pursued various types of professional credentials that include but are no longer limited to bachelor’s degrees. These students enroll for many reasons, especially to become more effective or competitive in their current jobs.97

In the 21st-century economy, higher levels of educational attainment correlate to higher earnings in a given field. However, earnings can vary greatly from field to field, so skills and field of training are an important currency in job markets.98 If workers take on a larger variety of jobs over their career, or if skills requirements shift (whether due to technology or other economic factors), they will need to learn a more diverse set of

___________________

95 The Bureau of Labor Statistics has projected roughly 3.8 million new health care and social assistance jobs between 2014 and 2024, nearly 40% of all new jobs; see Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Table 2, Employment by Major Industry Sector,” Economic News Release, last modified December 8, 2015, http://www.bls.gov/news.release/ecopro.t02.htm.

96 B. Reskin and P. Roos, 1990, Job Queues, Gender Queues, Temple University Press, Philadelphia, Pa.; C. Williams, 1995, Still a Man’s World: Men Who Do Women’s Work, University of California Press, Berkeley, Calif.

97 A.P. Carnevale, N. Smith, M. Melton, and E.W. Price, 2015, Learning While Earning: The New Normal, Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, Washington, D.C.

98 A. Carnevale, S.J. Rose, and B. Cheah, 2011, The College Payoff: Education, Occupations, Lifetime Earnings, Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, Washington, D.C.

skills over time. This requires an educational system that provides access to continuing education relevant to the changing nature of work. It also requires a primary and secondary education that prepares students to be flexible learners who are capable of acquiring more diverse skills over time.

At the same time, IT is changing how education is provided—both the nature of coursework, and access to education via the Internet. As described in the section “Educational Tools and Platforms” in Chapter 2, recent years have witnessed a growth in the availability of online classes over the Internet, creating a new mechanism for access to education by students worldwide. Organizations such as Coursera, edX, and Khan Academy offer hundreds of online courses, and companies such as Udacity now team with employers to create and deliver online training in areas that enable employees to move up the career ladder and acquire skills in high demand. The promise of change in online education is enabled by a combination of broad access to the Internet, ease of creating video and recorded lectures and hosting them (e.g., on YouTube), and innovations in combining lecture-style training, online exercises, and crowd-sourced grading. Although this model of online education is still young and its eventual impact unproven, it does offer the promise of a potentially significant increase in access to education. By globalizing the delivery of education, it also holds the potential of giving students access to the best teachers worldwide, although the extent of this access will be limited to the volume of participating students. Despite the increased availability of courses and educational materials over the Internet, there is a large skew in the utility of this content to different types of students and in the educational topics covered. Furthermore, as discussed in Chapter 2, there is evidence that online courses benefit most those students who already have well-developed learning skills and a strong educational background, and may leave students already behind in education even further behind.