4

Solutions

The next session featured two presentations focusing on the importance of health literacy and health insurance literacy with respect to health insurance reform. Catina O’Leary, president and chief executive officer of Health Literacy Missouri, spoke about how health literacy and health insurance literacy can contribute to solving the challenges and addressing issues regarding enrollment and use of insurance. Judith Hibbard, professor of health policy at the University of Oregon, presented a continuum of solutions with examples relevant to the issues raised in the prior session. Bernard Rosof moderated an open discussion following the two presentations.

HEALTH LITERACY AND HEALTH INSURANCE LITERACY CAN CONTRIBUTE TO ADDRESSING THE CHALLENGES1

For O’Leary, there is significant overlap between health literacy and health insurance literacy when thinking about the three tasks people are being asked to accomplish with regard to health insurance: get health insurance, keep it, and use it. Each task requires a certain skill set and each is complex. Getting insurance requires an individual to find and evaluate information about dozens of available plans and use that information to choose the best plan for his/her situation, or in some cases, to choose no

___________________

1 This section is based on the presentation by Catina O’Leary, president and chief executive officer of Health Literacy Missouri, and the statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

plan if none of the choices work. In Missouri, for example, some of the few choices consumers have are not affordable. “We have to think about what that means for folks who are faced with that choice of using very limited funds to pay for something that they may or may not use and the choice between that and eating,” said O’Leary.

For some people, the big hurdle is keeping their insurance by paying the monthly premium and then renewing and reenrolling during the next enrollment period. For others, using their insurance is the biggest obstacle. O’Leary noted that presenters had already discussed how using insurance is a learned skill, but on top of that, for many people finding a doctor on their plan and then getting their first appointment can take a long time and require a great deal of effort. “It is a big job we are asking folks to do,” said O’Leary, “but these tasks are all associated with basic health literacy skills, and we have strategies that we apply to other parts of health care that can be used to help people here.”

With the intent of using Missouri as an example of what is possible, O’Leary described the Cover Missouri Coalition, a project of the Missouri Foundation for Health with the goals of promoting quality affordable health coverage for every Missourian, lowering the rate of uninsured state residents to 5 percent by 2018, and improving the health insurance literacy of Missourians. She noted that Missouri is a non-expansion state and not much progress would be made in getting people enrolled unless some other organization got involved, and in this case it was a foundation with the resources to focus attention on a problem of this magnitude.

The coalition includes a set of regional hubs, Missouri Foundation of Health grantees, and some 900 community-based partners (see Figure 4-1). The hubs are on-the-ground organizations around the state that worked closely to identify key issues and barriers the coalition needed to address, while the grantees received navigator and assister funds that supplemented whatever else they got from government sources. In addition, the coalition has a support team consisting of five components, one of which is Health Literacy Missouri, which focuses on increasing health insurance literacy. “We were very specifically funded to work with the navigators and assisters to help them learn health literacy, but also to think about how the things that they are doing in the community needed support,” explained O’Leary. The other support team members include StratCommRx, a company that works to organize the 900 community groups by facilitating monthly meetings and weekly phone calls. FleishmanHillard and Missouri Health Care for All work together on awareness, communication, and advocacy. Community Catalyst provides technical assistance, about which Dara Taylor, director of Community Catalyst’s Expanding Coverage through Consumer Assistance Program, would talk in the next panel session. Washington University in St. Louis evaluates the program and helps the coalition both stay

NOTE: MFH = Missouri Foundation for Health.

SOURCES: Missouri Foundation for Health, 2016, presentation by O’Leary, July 21, 2016.

on track and look at areas that need further attention as it works toward meeting its goals.

Health Literacy Missouri’s role in the coalition is to provide health insurance literacy support by developing clear resources to help consumers understand health insurance and improving assisters’ interactions with consumers. O’Leary and her colleagues also provide support and training to assisters. Though these were the tasks Health Literacy Missouri was funded to do initially, its involvement in the project evolved into a much bigger

collaborative process. “It was because we applied these basic health literacy strategies that we all know and love over and over again,” she explained.

These successful strategies, she said, rely on relationships among diverse stakeholders, including patients and consumers, insurers, government organizations, hospitals, community organizations, and the assisters and coalition health literacy working group. The insurers are important stakeholders because, as was noted in the previous session, they have a great deal of information. They are also a key driving force for how insurance plans are developed and what they cost. Government organizations are important stakeholders because they structure the affordable care plans, and hospitals in a non-Medicaid expansion state play an important role in how they partner with the community to deal with individuals who may not be able to afford any of the plans. The community organizations, which provide the assisters and were for the most part places where people went for care before they were insured, also see people when they first start using their health insurance. “Often, people want to go back to those places when they first get insured, so figuring out what those relationships look like and how to keep supporting them is important.”

O’Leary reminded the workshop participants that the importance of being connected to the community was stressed repeatedly in the previous sessions. “It is not always that I am connecting to the community, but somebody has to be connected to the community and that audience interaction,” said O’Leary. “Identifying who the person is who needs the service and learning how to talk to that person is critical in this work.”

When the coalition formed in 2012, there were 877,000 uninsured Missourians. In the first year, the coalition helped enroll 152,335 people. Year 2 saw enrollment reach 253,430, and the total after year 3 was 290,201, which ranks Missouri ninth in the nation, according to O’Leary. “We are proud of our work, particularly in a non-expansion state where people are really angry about health insurance and the fact that they are required to get it,” she said. When Missourians talk about health insurance, they use the term Obamacare as a pejorative, said O’Leary, and without a doubt everyone who remains uninsured in Missouri knows they are supposed to be insured. “These folks are not hiding or unreached,” she said. “These are people who actively make the decision that they either do not want to enroll now or maybe they do not want to ever enroll. This is not a lack of awareness for us.” Rather, she said, it is about people not yet at a stage of readiness to enroll and requires a conversation about personal philosophy and health behavior over time.

To identify the topics that were most difficult to explain to consumers and that consumers had trouble understanding, O’Leary and her colleagues relied on input from the Cover Missouri health insurance working group, which is made up of on-the-ground assisters who talk to the target audi-

ence every day. Then, working with its partners at Community Catalyst and FleishmanHillard, the Health Literacy Missouri team was able to create factually correct materials that it then took back to the working group to see if those materials were understandable and if they would work with the intended audience. Teach-back was part of this process, as was testing in the communities. “We used this rolling process to make sure we had materials that structured conversations and that supported the follow-up in conversations with families over time,” said O’Leary.

The assisters in the working group wanted worksheets, checklists, and other materials they could use to help consumers sort through all of the plan options. Not only did Health Literacy Missouri create those materials but they branded them, made them look good, and applied other strategies to improve health literacy so that, when the assisters saw the materials, they would feel good about using them with their clients. The materials were released to the assisters once they were tested for usability and understandability.

O’Leary and her colleagues also conducted focus groups around the state to identify gaps in knowledge among uninsured and newly insured Missourians, to find out how they like to get their health information, and to provide feedback on the materials. As was mentioned in the earlier discussions at this workshop, consumers want simple materials and information about health insurance, but they want to get those materials and information in person from someone in their community with whom they have a relationship. As one focus group participant said, “I just do better in life, no matter what I’m doing, if someone can explain it to me . . . if I have to read it, it’s going to take me 27,000 times to grasp it.” That is a literacy issue, said O’Leary, but it is also about confidence. “These assisters were really able to transfer confidence and competence to people over time,” she said.

In providing feedback on the materials, the consumers in the focus groups noted they prefer certain words to talk about health and health insurance, said O’Leary. For example, 70 percent of the consumers preferred “HealthCare.gov” instead of “Health Insurance Marketplace,” and 100 percent liked “doctor” over “primary care provider” or “health care professional.” Half of the participants wanted to use the word “fee” instead of “penalty” or “individual shared responsibility payment,” and 70 percent preferred “financial help” instead of “tax credits.” The state, she said, requires materials to use certain words, but workarounds are used regularly in providing health-literate care instructions that are not being applied here.

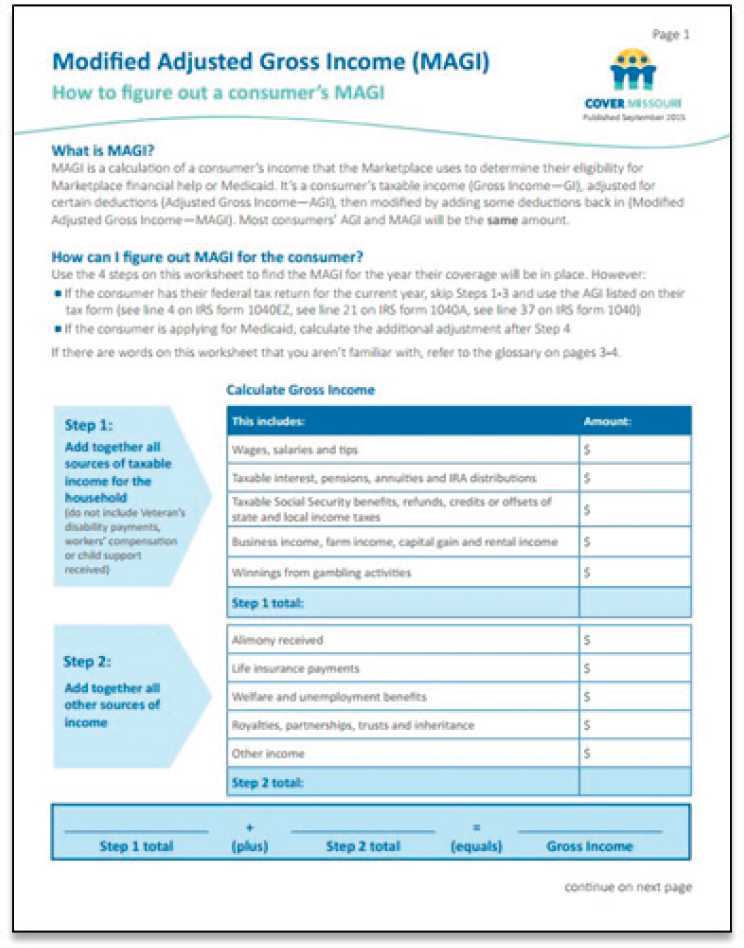

To help explain a challenging concept, such as modified adjusted gross income, or MAGI, O’Leary and her colleagues created written materials and spreadsheets that could be used to structure conversations, explain words, and walk a consumer through every step of the necessary calcu-

lations (see Figure 4-2). These materials enabled the assisters to avoid memorizing how to do these calculations. “There is no good reason why they have to remember this. It is not a test. It is building a relationship,” she explained. “We want to get to a goal of understanding together what we are supposed to do, and things like this made a difference.”

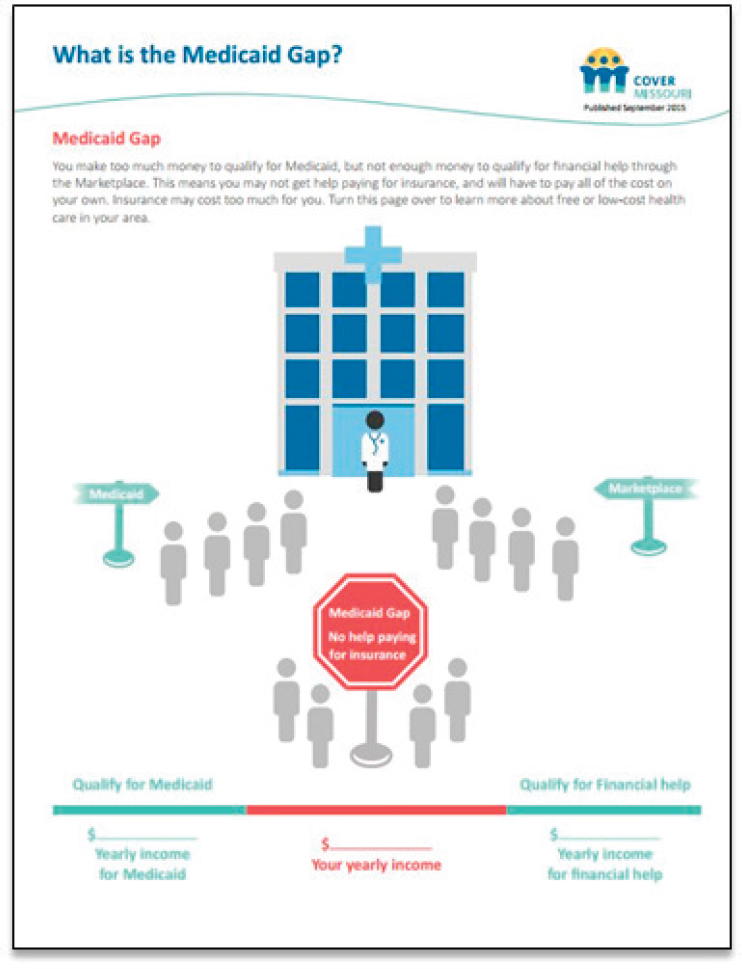

Another challenging concept was the Medicaid Gap, not in explaining what it is, but in helping people understand why they fell into the gap. The assisters, said O’Leary, reported this to be a difficult conversation and one for which they needed some materials to help them through that conversation. The resulting information sheet (see Figure 4-3) contains a graphic that the assister can use to illustrate how small changes in income could make a person eligible for Medicaid or able to use the marketplace. It also prompts a conversation about federally qualified health centers that offer free care in the community.

Health Literacy Missouri also created 10 videos to help health care professionals explain insurance topics such as preventive care, the Explanation of Benefits document, and appeals. These videos are all available online at www.youtube.com/covermissouri. O’Leary and her colleagues created online and in-person trainings and virtual “office hours” for tailored support, and they offer monthly webinars and in-person seminars tailored to the needs of specific communities or regions of the state. They also developed a series of eLearnings that health care professionals can work through prior to or immediately after open enrollment. The eLearnings helped them direct activities that were either ramping up or cooling down. Continually reminding health care professionals that these resources are available is important, she said. She noted, too, that she and her colleagues train the community organizations to deliver these materials and seminars so they can become independent and do work in their communities without the need to involve the coalition support team.

With regard to the strategies used with consumers, Health Literacy Missouri created print materials, some with worksheets, that consumers could take home with them and review without having to remember everything they heard from an assister. Consumers have told O’Leary and her colleagues that these graphics-rich, easy to understand materials are helpful. Health Literacy Missouri also developed a 10-video set that explains health insurance and the marketplace and provides guidance on choosing a plan as well as words to know. Six of the videos are in English, and four are in Spanish. While designed for consumers, the videos are also used by assisters to support their own learning. The assisters reported, too, that they would put these videos up on an iPad or computer screen and play them before meeting with clients as a means of better preparing their clients for the subsequent discussion. Social media are also used to share tips on how consumers can get the most from their health insurance and health care system.

SOURCES: Cover Missouri, September 2015, presentation by O’Leary, July 21, 2016.

SOURCES: Cover Missouri, September 2015, presentation by O’Leary, July 21, 2016.

Health Literacy Missouri has partnered with Missouri’s Family Support Division to conduct plain-language reviews and staff trainings with the goal of creating materials that relate to health and well-being, but the materials are not directly associated with the ACA and are simpler for consumers to understand. “We found in Missouri, like in other places, that the forms and materials people are asked to use and understand are pretty horrific,” said O’Leary. “We are working with the Missouri Department of Social Services on the food stamp program and others to help make these forms, materials, and letters more readable and usable.”

Health Literacy Missouri also has a partnership with the State of Oklahoma to provide technical assistance to increase health insurance literacy and health literacy for Oklahoma state employees. Referring to the idea that health insurance literacy is not just something for the uninsured, O’Leary said there are 38,000 State of Oklahoma employees and they, too, have a hard time understanding how to pick a health insurance plan. In fact, many employees were selecting the wrong plan or did not understand the details of their plan and had unanticipated expenses for medical care. “When we talk about who needs what, these are folks that we think know,” said O’Leary. “I think this is a testament to how hard this is, how clear we want to be and really how accessible everything needs to be as we go forward.” She and her team are now conducting health insurance literacy training for benefits coordinators and are using social media and webinars to educate employees.

In her final comments, O’Leary talked about the next steps needed to reach the people who are still uninsured and who are resource deprived. Through Cover Missouri, she and her colleagues are going to conduct a deep, engaged community strategy in four underresourced communities in the state. This strategy will entail forming partnerships with local newspapers and radio stations, the schools, local health departments, and local hospital systems. Her team will also go to county fairs and actively engage consumers to talk about what is important to them and their communities. The most important thing may not be health insurance, but rather wellness, health, and care, said O’Leary, and she suspects it will take time to make clear to consumers the connection between health and health insurance.

The challenge, said O’Leary, will be covering every corner of the state. “We are going to see what it is like to be in these rural communities and figure out what it means to apply these strategies with folks that are really hard to reach,” she explained. “How do we figure out how to do the work we need to do with them so we can move them toward health and wellness? We will try to reach and engage the remaining uninsured around health and health care coverage.” Part of this effort will involve supporting existing health and wellness and enrollment activities that already exist in the community and forming relationships, partnerships, and coalitions. One of the

key messages will be that some things are unpredictable—a broken arm or some other emergency—and health insurance is one way to prepare for the unexpected.

A CONTINUUM OF STRATEGIES TO HELP LOW-LITERACY CONSUMERS USE COMPARATIVE INFORMATION FOR CHOICE2

One focus of Judith Hibbard’s research is on how consumers use information to inform the choices they make. That is the lens she used to look at solutions for helping low-literacy consumers select the appropriate insurance plan. Using information to inform choice, said Hibbard, requires understanding the meanings of terms, processing multiple pieces of information, applying the information to one’s personal situation, and differentially weighing factors according to personal preferences. “Think about all of the different factors we are talking about—multiple cost factors, coverage factors, network factors—and for some exchanges and soon for all, the quality of care provided,” said Hibbard. The individual must give some relative weight to each of these and then pull all of the information together into a choice.

These decision tasks are difficult and burdensome for all human beings, said Hibbard. “We are not really wired to do this well,” she said. This burden is even greater when people have literacy or numeracy challenges, she added. When people are faced with this kind of complexity, the most common response is to take a shortcut, to make a decision based on one factor, usually one a person understands. Unfortunately, said Hibbard, in taking that shortcut people often undermine their own self-interest.

The good news, Hibbard said, is that for decades research has shown that the way information is presented can help overcome at least some of these difficulties. Simply reducing the cognitive burden by reducing the amount of information offered to the consumer and presenting it in plain language is one strategy that helps people use comparative information to make decisions. Small nudges to draw a person’s attention to something she may have overlooked is another strategy. Interpreting information for people—putting it on a good-to-bad scale, for example—can be a big help, as can calling out the best options.

Before presenting examples of these strategies, Hibbard discussed some of her recent research funded by the Jayne Koskinas Ted Giovanis Foundation for Health and Policy. This research looked at how people with different numeracy levels understood information commonly presented

___________________

2 This section is based on the presentation by Judith Hibbard, professor of health policy at the University of Oregon, and the statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

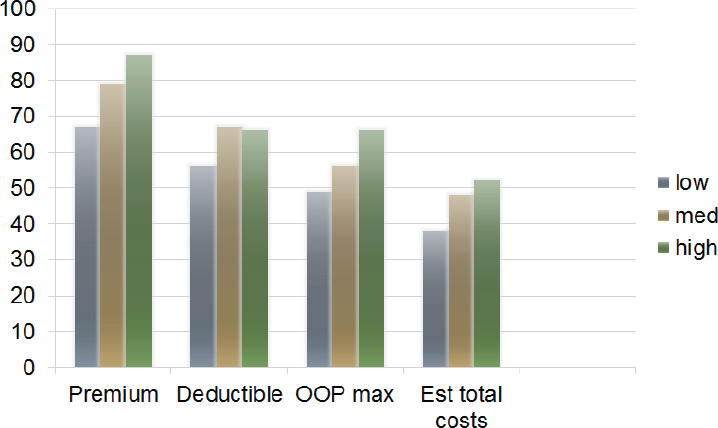

on health exchanges and how different ways of presenting that information affected the choices people made. In this study, people were randomly assigned to different approaches for presenting information and assessed for their understanding of certain terms. Individuals with lower numeracy, said Hibbard, were less likely to understand terms such as “premium,” “deductible,” “out-of-pocket maximum,” and “estimated total cost” (see Figure 4-4). Using a simplified data display, one not nearly as complicated as is presented on most exchanges, she and her collaborators looked at how numeracy level affected the ability to make a high-value choice, one where quality was good and cost was reasonable. “Again, there was a real difference in numeracy impacting the ability to make a high-value choice,” said Hibbard

Nudges and strategies that reduce the cognitive burden did help both high- and low-numeracy consumers choose high-value plans. In one experiment, for example, Hibbard’s team looked at the effect of summarizing information on premium and cost compared with presenting four different cost measures on the ability to choose a high-value plan, and the summarized information helped people choose high-value plans (Greene et al., 2016). They also looked at how the placement affected decisions. Some plans, for example, report quality of care information next to the plan name, while others put it next to cost information. In fact, putting the quality and cost

NOTE: Est = estimated; OOP = out-of-pocket maximum.

SOURCE: Presentation by Hibbard, July 21, 2016.

information together made it more likely that people would pay attention to that information and use it to choose a high-value plan.

One finding from this study, which Hibbard noted other researchers have also seen, is that people tend to make decisions based on premium alone. What her team also observed is that people with fair and poor health are making decisions based on premium alone, which is probably undermining their self-interest because their costs are going to be higher unless they pay attention to some of the other cost factors. To address this problem, she and her collaborators conducted experiments to see if they could present information in a way that would draw people’s attention to their estimated total cost, not just the plan premium. In one experiment, they listed seven plan choices and ordered them by estimated yearly cost, and doing so increased the number of people who made the choice based on estimated costs. “It was a nudge to consider something beyond premium,” said Hibbard.

Another experiment looked at the effect that the amount and placement of information had on the decision process. One group saw a great deal of information, but premium and yearly estimated cost were displayed prominently. Another group saw the same information, but the deductible and premium were tucked under the plan name, which drew less attention to the premium. Those individuals in the latter group were more likely to make their choice based on the lower estimated yearly cost. A different approach to helping people make a better choice is to call out best options, which in essence is doing the cognitive work for people (see Figure 4-5).

Word icons can also help people by reducing the cognitive burden by highlighting and interpreting meaning for people. Word icons, said Hibbard, map a good-to-bad scale onto information. They have a shape, color, and word embedded on them, eliminating the need to consult a legend to understand the figure, and they display data in a way that should allow someone to identify the best options in seconds, which Hibbard said is all the time many users will spend looking at information. As an example of how word icons can help consumers with their choices, Hibbard showed two charts (see Figure 4-6). One chart presented quality data in terms of stars, a common ranking tool that consumers understand, and the other used word icons. The latter approach allowed people to see the best options quickly, said Hibbard, making it more likely they will use the information.

The bottom line, said Hibbard, is that making the task of assessing information easier means that more people will incorporate information into their choices. “These strategies help everyone, but they help those with less skill the most,” she said. Lower skilled individuals also rely more on these approaches than higher skilled individuals.

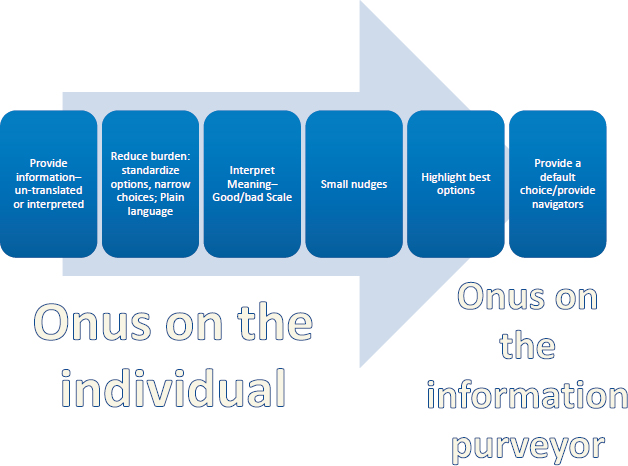

In summary, Hibbard said one way to think about these findings is that there is a continuum of strategies for presenting information so that

NOTE: HMO = health maintenance organization; PPO = preferred provider organization.

SOURCE: Presentation by Hibbard, July 21, 2016.

it might help those with weaker literacy skills (see Figure 4-7). At one end of the continuum, information is presented to people with no translation or interpretation, which she said is what many health exchanges do. At the other end of the continuum, navigators do all the work. Between those two ends are the strategies that can help many people. These strategies start with reducing the cognitive burden, and they can be accomplished with standardization, narrowing options, and using plain language. The strategies can then help people by putting more meaning on data and helping them put a good-to-bad scale on information. Small nudges, explained Hibbard, can help people in cases where it is known that they are more likely to make decision errors and draw their attention to information they are not likely to use in making their choice. Going further, highlighting best options, and using decisions tools informed by the client’s stated criteria about what is important to them remove even more of the cognitive burden from the consumer.

Today, said Hibbard, most efforts focus on reducing the cognitive burden, with fewer efforts using nudges or interpreting data for users. “The further you move to the right on the continuum, the more responsibility, resources, and political capital are needed by the information sponsor,” said Hibbard. As far as which strategy to deploy and how far to the right

SOURCE: Presentation by Hibbard, July 21, 2016.

to move on the continuum, she said that depends on the difficulty of the decision task. “Ultimately, we want to be able to move to a more evidence-based approach about how we provide information to consumers so that we know it is more likely to be understood, processed, and actually applied in making a choice,” she said in closing.

SOURCE: Presentation by Hibbard, July 21, 2016.

DISCUSSION

Alicia Fernandez from the University of California, San Francisco, and San Francisco General Hospital asked the two panelists if they have seen any discussions about default enrollment for health insurance. Hibbard replied that having a default choice is one way to help people, but how much it helps depends on how it is done in practice. If the default choice is determined by characteristics and needs of the user, that can be a good approach. However, most default choices are more along the lines of a random spin of a wheel, she said. She also said she is unaware of any discussions among commercial insurers about a default plan, but that idea would be worth exploring.

Fernandez also asked O’Leary how much the navigators in Missouri are allowed to explain to people their health care rights, particularly as they relate to language interpreter services. O’Leary responded that the coalition has created supports for language interpretation, and one of the videos her team prepared discusses how to work with interpreters. She noted, too, that, during the early part of Health Literacy Missouri’s health literacy work, they had a subcontract with the International Institute of St. Louis,

an organization that works with refugees and resettlements. Through that relationship, Health Literacy Missouri was able to translate most of its materials into nine languages and use the Institute as a resource for interpretation. Dara Taylor, O’Leary’s colleague at Community Catalyst, said the law does not require that navigators and assisters inform their clients about interpretation services, but that the majority of them do so anyway.

Winston Wong from Kaiser Permanente commented that, even before asking how people make choices, it is necessary to ask how they establish value in terms of trying to put choice in front of them. In that regard, he asked O’Leary how health literacy plays out in a non-Medicaid expansion state and whether there are real or subtle differences in terms of how health literacy is able to convey the evidence that people will be healthier if they have access to health insurance against a cultural and political background that wants the choice of having or not having health insurance. “I think this is really critical in terms of understanding the interplay between these different aspects and how health literacy gets expressed within that context,” said Wong.

O’Leary replied that she could not agree more, and that is why the coalition has taken a community approach to deal with the variability in attitudes within the state and to be responsive in its communications in a way that reflects where those communities are starting with respect to health insurance. In the end, it made a difference when framing this issue in terms of a community’s values and what was important to that community, said O’Leary. Referring to Michael Paasche-Orlow’s comment during the previous discussion session about training and social work, O’Leary said she was trained as a social worker, and she starts every conversation from the premise that the goal is to find out what is important to each individual and what he or she values, and to go from there while also reflecting the needs of the community. For example, she tries to consider what it means to the community hospital when many people decide they are not going to get health insurance.

Coming back to Wong’s point about value, Eric Ellsworth from Consumers’ Checkbook said that people make value-based decisions all the time when they choose apartments and cars, but that the problem with health insurance is that consumers do not have the mental background to think about value in that context. He wanted to know what steps can be taken to help accelerate the ability of consumers to start thinking about the value of health care and health insurance. “What can we do to get people to be able to take in more of that information and build their mental database?” he asked.

Hibbard replied that one step would be to help the consumer understand the highest-priority items they should be considering in a value equation, and then present the necessary information in a manner the individual

can process. “Give them estimated yearly cost and premium and they could probably make a good decision based on those two things,” said Hibbard. “When we overwhelm people with too much information it all gets lost.”

Linda Harris from the HHS Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion had a question related to prevention. Part of her office’s task, she said, is to inform the public about the preventive services they need. She and her colleagues are finding a great deal of the attention on the ACA is focused on coverage while little attention is paid to encouraging people to take advantage of the free preventive services. She wanted to know if the videos Health Literacy Missouri created help people make decisions about the preventive services people can access and which ones they need if the evidence is not clear. She also asked Hibbard how the principles she has identified with respect to choice can be applied to preventive services.

O’Leary replied that the videos her team developed are for use by both navigators and consumers, in part because the two groups overlap, but also because people go back to the navigators in their communities to get advice on how to use their insurance, which includes accessing preventive services. In Missouri, she and her colleagues have worked with providers to give them the health literacy skills to discuss options and resources with their patients, though the providers have not gotten very involved in promoting these preventive services. For the most part, messages about prevention are coming from in-person discussions between consumers and the navigators who helped them get their insurance. One issue that needs to be addressed, she added, is that most people have no idea what a preventive care visit entails, and many believe it is just a way to get people into the office for services they try to avoid, such as shots. Another concern she has heard is that prevention visits turn into something else that costs money. “How we undo that narrative is a challenge, or if it is happening, how do we help providers understand that if you go for a preventive visit, it has to be a preventive visit and you need them to come back for something else?” asked O’Leary.

Hibbard said that drawing people’s attention to preventive services has been a challenge because most people do not realize they are free. A way to counteract that, she explained, is to highlight that information when working with people during enrollment and to highlight it in discussions on how to use coverage. Referring to Harris’s mention of unclear evidence, Hibbard commented that ambiguity about an issue or information increases the likelihood that an individual will not pay attention or act.

Marin Allen with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) asked Hibbard about the appropriateness of nudging when doing so may be taking away some of the freedom of individuals to make their own choices and depriving them of the skills to make those choices on their own. One concern was that consumers will only see their navigators once and then be stuck trying to make subsequent decisions without help. Hibbard said

she has thought about this and that is why she said that moving along the continuum of choices puts more responsibility on the information provider to understand where a person is to counteract decision errors. At the same time, she said there is no such thing as an objective data display or comparative display. “Whatever we do, we are influencing people,” she said, “and most of the time we do not know how a data display or the way we are comparing things is influencing people.” Given that, she asked, “Is it not better to know and do it in an informed way than to do it in a way that you have no idea how it is influencing people?”

O’Leary said she has been hearing in Missouri that people were going back to their navigators whenever they received a bill for services to help them pay it and make sure it was counted. “They were very worried that if they did that on their own, even with a confirmation number it would not be counted and their plan would be cancelled,” said O’Leary. While she acknowledged Allen’s concern, O’Leary said that building coalitions with community-based organizations and capitalizing on the trust community members have in those organizations creates an avenue for getting ongoing help and advice. Allen replied that the situation in Missouri may be different than in some of the large cities, but she assumes that the same avenue for getting help and advice will not develop when dealing with larger numbers of people.

Paasche-Orlow noted the importance of financial literacy in this discussion given that health care costs are the leading cause of personal bankruptcy in the United States. He asked how financial literacy is incorporated into training and into the information conveyed to consumers. In particular, he noted that people who live in Health Professional Shortage Areas are concerned less with getting preventive care than they are about avoiding financial disaster in the event of a medical emergency. O’Leary replied that many of the tools her team has developed are meant to address the issue of cost in relation to the conditions an individual has. These tools help the individual work through the series of choices to help them weigh options and make decisions about the care they may need and cost. The approach her team has taken has been to create materials that provide the information consumers need to make those choices and the training for navigators that enables them to walk through the information. “You can script this out and help people work through the finances, think about what money they have available, and help them make an informed choice,” said O’Leary. When the navigators follow this process and help identify all of the big bucket items, people can go forward and make good choices.

Ruth Parker said she has been thinking about how to operationalize affordability, which she said is still at the forefront of the ACA. “How do you really take affordability and make that a concept that is part of your choice?” she asked. What she wanted to know was how to create an

evidence-based approach to put more of the onus for helping individuals understand affordability on the information provider so that it becomes more navigable. “Do we approach that any differently when the issue of affordability is front and center in the minds of people? Do we know anything from an evidence standpoint about how we do that for people who are having trouble deciding whether or not they can even afford it?” asked Parker.

Hibbard responded that, if the navigators can learn something from the decision makers about their income, health status, and history with using care, it should be possible to identify the most affordable plans for those individuals and for the navigator to call those plans out for them. “Part of the difficulty people face when they are looking at such complex information is they are overwhelmed by the number of things they need to consider,” said Hibbard. She noted that the goal, then, should be to design a decision process that walks them through each of those pieces of information, and then talk about affordability and order the plans based on affordability if that is a key issue for a particular individual.

Amy Cueva asked O’Leary if the community coalitions include houses of worship, Walmart, and frontline clinical workers. O’Leary replied yes to houses of worship and frontline clinical workers, but not specifically with regard to Walmart. Cueva noted that Walmart is holding a national health day where it will be providing immunizations and is trying other interesting approaches to promoting healthy living. O’Leary said involving companies such as Walmart is a good idea and one that she will take back to Missouri.

Cueva then asked Hibbard if she had done any research on scenario modeling that would help people envision how different scenarios would affect a particular family. Hibbard replied that she has not, but that would be a productive direction to pursue. Elisabeth Benjamin noted that purchasing health insurance is so much more complicated than buying a car or renting an apartment. “Look at all of the moving pieces. You have co-pays, premiums, deductibles, co-insurance, maximum out-of-pocket expenses, networks, and HMO [health maintenance organization] versus PPO [preferred provider organization], and that does not even include tax credits and financial penalties,” she said. The only solution to health insurance literacy, she said, is to simplify the whole system. “It is not fair to put this on consumers.”

Fernandez, agreeing with Benjamin, said the goal should be to make the system work better for people, not to teach people how to understand such an overly complicated system. As an example, she said the Internal Revenue Service now allows small businesses to automatically enroll employees in a 401(k) plan and select investment allocations with a series of safeguards. “What I would like to encourage us to do is to think through the range of issues from nudges to automatic enrollment that would protect people and

allow them to be able to make better choices that would be optimal for their situation,” said Fernandez.

O’Leary said that two systems need dismantling—health care and health insurance. “I do not know how we dismantle both of those simultaneously,” said O’Leary. She also commented that it is a slow process to move people forward in terms of how they use health insurance and how they learn to take care of themselves from a health perspective in conjunction with using their health insurance. “This is the layering of health literacy and health insurance literacy,” she said.

Cindy Brach remarked that there was a great deal of discussion in this session about not choosing plans based just on premiums, but there is still the underlying assumption that money is the driving force behind choice. Taking a page from work on shared decision making for medical care, one of the emphases is on eliciting values and preferences. “While we need to reduce the cognitive load and simplify things, what we are at risk of losing is what is most important to the person who is making that selection. We vary in terms of how risk-averse we are. We vary in terms of how much does the language access network matter to me,” said Brach. Her suggestion was that more thought needs to be given to the ways in which the system, which is not being dismantled, can work better for people.