11

Promising and Effective Practices in Assessment of Dual Language Learners’ and English Learners’ Educational Progress

Assessment of the educational progress of dual language learners (DLLs) and English learners (ELs)1 can provide concrete and actionable evidence of their learning. Sound assessment provides students with feedback on their learning, teachers with information that can be used to shape instruction and communicate with parents on the progress of their children, school leaders with information on areas of strength and weakness in instruction, and system leaders with information on the overall performance of their programs.

Well-established standards for assessing students and education systems developed through a joint effort of the American Educational Research Association (AERA), American Psychological Association (APA), and National Council on Measurement in Education (NCME) exist to guide practice (American Educational Research Association et al., 2014). According to these standards, the concept of validity is central to all assessment; it is the cornerstone for establishing the fairness of assessments, including those used with DLLs/ELs. There is a gap, however, between these professional standards, developed by consensus among relevant disciplines in the scientific community, and how assessments of DLLs/ELs at the individual student and system levels are actually conducted. Current practices vary across

___________________

1 When referring to children ages birth to 5 in their homes, communities, or early care and education programs, this report uses the term “dual language learners” or “DLLs.” When referring to children ages 5 and older in the pre-K to 12 education system, the term “English learners” or “ELs” is used. When referring to the broader group of children and adolescents ages birth to 21, the term “DLLs/ELs” is used.

states and districts. States will have primary responsibility for these assessments as the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) of 2015 is implemented in school year 2017-2018, with its directive that school districts within a state share common assessment practices for student identification and exit from EL status.

The heterogeneity of DLLs/ELs with respect to age, first language, literacy, and access to educational services, as well as their family and community circumstances (see Chapter 3), requires careful consideration during the assessment process and the interpretation of results. Particularly for DLLs/ELs, assessment of academic learning needs to be considered in conjunction with assessment of English language development or bilingual proficiency.

This chapter summarizes what is known from research on assessment measures and practices first for DLLs and then for ELs. The discussion includes the committee’s analysis of challenges in assessment design and implementation that need further investigation. The chapter ends with the committee’s conclusions on promising and effective assessment practices for DLLs/ELs.

ASSESSMENT OF DUAL LANGUAGE LEARNERS

A central tenet of selecting appropriate assessment instruments is that the purpose of the assessment must guide the choice of measures, the method of data collection, and the content of the assessment (Espinosa and Gutiérrez-Clellen, 2013; Peña and Halle, 2011). This principle is clearly stated in the National Research Council (2008, p. 2) report Early Childhood Assessment: Why, What, and How: “Different purposes require different types of assessments, and the evidentiary base that supports the use of an assessment for one purpose may not be suitable for another.” The National Education Goals Panel established four main purposes for early care and education (ECE) assessments: to promote learning and development of individual children; to identify children with special needs and health conditions for intervention purposes; to monitor trends in programs and evaluate program effectiveness; and to obtain benchmark data for accountability purposes at the local, state, and national levels (Shepard et al., 1998). Each of these purposes requires specific technical standards and assessment approaches and has inherent potential for cultural and linguistic bias. As there are unique considerations and recommendations for assessing DLLs depending on the purpose of the assessment, it is critical that ECE assessors clearly understand the purpose for assessment and match instruments and procedures to the stated purpose.

Accurate assessment of DLLs’ development is critical for enhancing the quality of their care and education, as well as for understanding and improv-

ing the effectiveness of specific strategies for individual children (Espinosa and García, 2012; Espinosa and Gutiérrez-Clellen, 2013; Espinosa and López, 2007). The rapid increase in the numbers of young children who speak a language other than English in the home and attend ECE programs, combined with the expansion of state and federal funding for ECE services that carry accountability requirements, means that local and state assessment systems must be valid and appropriate for DLLs. As stated in the above-referenced National Research Council report, “Given the large and increasing size of the DLL population in the United States, the current focus on testing and accountability, and the documented deficits in current assessment practices, improvements are critical.” (National Research Council, 2008, p. 258). The report goes on to summarize the recommendations from the National Association for the Education of Young Children (2005) on fair assessment of DLLs, including the use of developmental screenings, the need for linguistically and culturally appropriate assessments, a focus on improving curriculum and instruction with multiple methods and measures, the use of multidisciplinary teams that include qualified bilingual and bicultural assessors collecting data over time, the need for caution when interpreting results of standardized assessments, and inclusion of families in all aspects of the assessment process.

Virtually all experts on ECE assessment have cautioned against the use of single assessments at one point in time to identify young children’s developmental status and learning needs across multiple domains of development (Daily et al., 2010; Meisels, 1999; National Research Council, 2008). Experts agree that a single assessment measure should never be used for making important educational decisions, such as those related to eligibility for services or rate of educational progress. All young children demonstrate highly variable and dynamic development depending on the context and task demands; they are also notoriously “bad” test takers with limited attention spans and frequently misunderstand the directions or task demands, which may lead to incorrect answers (Meisels, 2007; Stevens and DeBord, 2001). These challenges are compounded when children are still mastering their home or first language while also acquiring a second language during this period of rapid development.

To assess DLLs accurately, assessment professionals and ECE educators need to consider the unique aspects of linguistic and cognitive development associated with acquiring two languages during the earliest years, as well as the social and cultural contexts that influence these children’s development. (See Chapter 4 for fuller discussion of the sociocultural contexts for the development of DLLs.) Important individual and contextual differences unique to the experience of growing up with more than one language will affect the development of essential skills that are often part of school readiness assessments. DLLs, for example, are much more likely than their

monolingual English-speaking peers to have parents with low levels of formal education, to live in low-income families, to live in two-parent homes, and to be raised in cultural contexts that may not reflect majority culture norms (Capps et al., 2005; Espinosa, 2007; Hernandez, 2006).

Latino Spanish-speaking DLLs often have language needs that have not been identified or addressed (Espinosa and Gutiérrez-Clellen, 2013) and can lead to depressed language abilities at kindergarten entry (Fuller et al., 2015). DLLs’ first and second language and literacy development also has been linked to differences in home language experiences (Hammer et al., 2011), the timing and reasons for family immigration (Portes and Rumbaut, 2014), the age and circumstances of their first exposure to English (Hammer et al., 2011), and their families’ specific resiliencies and strengths (Fuligni et al., 2013).

All ECE administrators, staff, and teachers need to understand the impact of these sociocultural and language learning contexts on DLLs’ development. To individualize interactions and instruction, ECE assessors need to consider the complexity and impact of these factors and then carefully select assessment instruments and procedures that match the purpose for the assessment and the characteristics of the children. Thus, the first step in ECE assessment is to collect information from the family about the DLL’s early language and learning environments so these contextual factors can be carefully considered in the selection of assessment instruments, as well as in the interpretation of results and in educational decisions. Researchers have found stronger relationships between parents’ reports of their children’s language abilities than between teachers’ reports and direct child assessments, particularly in the area of vocabulary knowledge (Vagh et al., 2009). Thus it is important that family language surveys or interviews be available in the languages families speak and include questions about which language a child first learned to speak, the language of the child’s primary caregiver, the age of the child when first exposed to English, and the language spoken by other adults and peers who interact with the child regularly.

Language of Assessment

The majority of ECE assessment experts, along with the Office of Head Start (OHS) and several states, recommend that DLLs be assessed in both of their languages because assessing a DLL only in English will underestimate his or her knowledge and true abilities (California Department of Education, 2012; Espinosa and Gutiérrez-Clellen, 2013; Office of Head Start, 2015; Peña and Halle, 2011). When a DLL is assessed in only one language, concepts or vocabulary words the child knows in another language will not be represented in the results (see Chapter 4). Few states have explicit guidelines for assessing DLLs (Espinosa and Calderon, 2015); however,

the federal government and several states (e.g., California and Illinois) currently require that assessments be conducted in both English and the child’s home language (California Department of Education, 2012, 2015a; Illinois Department of Education, 2013; Office of Head Start, 2015). The California Department of Education, Child Development Division (CDE/CDD), for example, has issued guidelines on the importance of a teacher or other adult being proficient in the child’s home language when assessments are conducted (California Department of Education, 2012). The guidelines stress the importance of the first language as a foundation for continued development: the development of language and literacy skills in a child’s first language is important for the development of skills in a second language, and therefore should be considered as the foundational step toward learning English (see also Chapter 4).

According to the new Head Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework (Office of Head Start, 2015, p. 4), moreover, “Children who are DLLs must be allowed to demonstrate the skills, behaviors, and knowledge in the Framework in the home language, English, or both languages.” In addition, the National Center on Cultural and Linguistic Responsiveness has issued guidelines on how to conduct developmental screenings of DLLs in their home language and English when no appropriate standardized measures are available.2

These recent assessment requirements reflect a growing consensus among assessment professionals and ECE policy makers that although the field does not have adequate instrumentation with which to conduct standardized assessments in all of the languages children and families speak, there are methods for determining DLL children’s competencies in multiple languages, and this information is critical in planning appropriate interventions (Gutiérrez-Clellen, 1999; Gutiérrez-Clellen et al., 2012). As noted above, many language skills and concepts learned in the child’s first language have been shown to facilitate English language learning (see Chapter 4). For example, once a child knows some math concepts, such as the number 3, in the home language, the child is also likely to know the concept in the second language and needs to learn only the new vocabulary, not the concept (Sarnecka et al., 2011).

Given the large variations in preschool DLLs’ amount and quality of English exposure as well as home language development (see Chapter 4), they may show uneven progress between the two languages, depending on the language tasks involved. Because of this variability and the importance of language to all academic achievement, it is impossible to obtain an accurate assessment of a DLL’s developmental status and instructional needs

___________________

2 Available: https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/hslc/tta-system/cultural-linguistic/fcp/docs/Screening-dual-language-learners.pdf [February 23, 2017].

without examining the child’s skills in both languages. A child who demonstrates very little English proficiency may be in the early stages of second language acquisition but have well-developed skills in the home language, while another child that demonstrates difficulties in both English and the home language should be referred for an evaluation to determine whether special services are needed (see Chapter 8). Thus before making a referral decision, assessors need to consider each DLL’s language abilities in both the home language and English: if the child is very delayed in English but shows typical skills in the home language, the child most likely has had few opportunities to learn English and needs systematic high-quality English language development (see Chapters 4 and 6). If the child has a language delay, it will show up in both languages (see Chapter 8).

It is important to note that many researchers have expressed serious validity concerns about the use of standardized measures of DLLs’ English proficiency (Espinosa, 2008). Some assessment error is due to norming samples, complexity of language used, and administration procedures. To compensate for the psychometric weaknesses of current standardized tests of language proficiency within the DLL population, most researchers have recommended that assessors use multiple measures administered by bilingual, bicultural, multidisciplinary team members. These measures may include standardized tests and curriculum-embedded assessments in addition to narrative language samples and observation of children’s language usage in natural settings (August and Shanahan, 2006; Gutiérrez-Clellen et al., 2006; National Association for the Education of Young Children, 2005; Neill, 2005).

Having qualified ECE assessors who are knowledgeable about the process of first and second language development during the early years is essential to understanding, interpreting, and applying the results of any assessment of DLLs. Ensuring these assessor/teacher competencies requires increased investments for ECE professionals, as discussed below.

Special Considerations for Infants and Toddlers

During the infant-toddler years (birth to 3), assessment typically includes developmental screening, observation, and ongoing assessment. The use of standardized achievement measures is not recommended for this age range. ECE providers typically observe children’s behavior, language use, and progress across all domains of development in natural settings to document their growth and identify any potential learning problems. The focus of the observations is usually aligned with the major curricular goals of the program—for example, whether the child regularly shows comprehension of simple sentences by following one- or two-step directions. Although programs rarely administer standardized measures to assess individual DLLs’

progress during these years, they often use standardized observation tools that track the children’s learning over time (Espinosa and Gutiérrez-Clellen, 2013). One such tool, developed by the California Department of Education (2015b), is the Desired Results Developmental Profile for Infants and Toddlers (DRDP), which is required in all state-supported infant-toddler programs. Observational methods such as the DRDP that are organized around educationally significant outcomes, administered repeatedly over time, and include families’ perspectives are recommended by the leading ECE professional associations (National Association for the Education of Young Children and National Association of Early Childhood Specialists in State Departments of Education, 2003; National Research Council, 2008).

These observational assessments can be thought of as formative because their results are used to plan for individualized interactions and activities to support the child’s progress. All of the recommended practices for screening and assessing infants and toddlers apply to DLLs (see Greenspan and Meisels, 1996), but must be augmented by assessors who are proficient in the child’s home language and knowledgeable about the child’s home culture (Espinosa and Gutiérrez-Clellen, 2013; Peña and Halle, 2011).

Assessment Purposes and Procedures for Preschool DLLs

Language Proficiency

ECE assessors must first determine a DLL’s proficiency in both English and the home language, as well as the distribution of knowledge across the two languages, in order to design appropriate language interventions (Ackerman and Tazi, 2015). DLLs, whether simultaneous or sequential bilinguals (see Chapter 4), typically have a dominant language, even though the differences may be subtle. Researchers have documented that most DLLs have a larger, or a specialized, vocabulary, along with greater grammatical proficiency and mastery of the linguistic structure, in one language (Paradis et al., 2011; Pearson, 2002). Typically, this is the language the child learned earliest and with which he or she has the most experience, uses more fluidly, and often prefers to use. Information provided by parents can be used as a guide in determining which language is dominant. In conducting developmental screenings or standardized assessments of language proficiency, assessment experts recommend that preschool DLLs be assessed in their dominant language first to determine the upper limits of their linguistic and cognitive abilities (Peña and Halle, 2011).

The specific measures and methods used to assess a child’s language proficiency can impact the assessment results. For example, a child’s English proficiency can be overestimated when a single measure is used (Brassard and Boehm, 2007; Garcia et al., 2010). Scores also can fluctuate depend-

ing on whether the measure is English-only, a sum of both languages, or based on conceptual scoring (Bandel et al., 2012). In addition, there are no national definitions of what constitutes English proficiency during the preschool years, and the number of psychometrically strong language proficiency measures for preschool DLLs is limited (Barrueco et al., 2012). Therefore, a child’s designation as proficient may depend on the specific measure used and whether the assessment is based on observational data or a language assessment administered directly to the child, as well as local norms and what is expected for kindergarten entry in different communities (Ackerman and Tazi, 2015; Hauck et al., 2013; Lara et al., 2007). Therefore, the interpretation of results of standardized language tests for DLLs needs to be treated with caution and combined with other types of assessment data, such as observational records and detailed family histories.

Assessment to Improve Instruction and Individualize Practices

One of the most important purposes for ECE assessment is to guide teachers’ instructional decision making and monitor each child’s progress toward meeting important program goals. This is especially critical for DLLs as formative progress data collected throughout the year can be used to modify and individualize classroom strategies and identify areas of weakness that need more attention (Ackerman and Tazi, 2015; Espinosa and Gutiérrez-Clellen, 2013). When assessing DLLs’ progress toward meeting program curriculum goals, it is important that progress be measured against what is typically expected of children growing up with more than one language (López, 2012). ECE assessors need to understand thoroughly the process of first and second language acquisition, the stages of second language acquisition during the preschool years, and the influences on dual language development (see Chapter 4) in order to make judgments a DLL’s progress and whether it is within normal ranges. If the program is implementing a dual language approach with goals for bilingualism and biliteracy, the DLL’s knowledge and progress need to be assessed continually in both languages. (See Espinosa and López [2007] and National Research Council [2008] for discussion of the potential for assessment bias when ECE teachers do not understand DLLs’ language and culture.)

During the ECE years, assessments used to inform teachers and improve learning are frequently based on careful observations of children’s behavior and use of language conducted repeatedly throughout the school year. The documentation of children’s accomplishments can then be applied to rating scales, checklists, work samples, and portfolios completed over time (National Association for the Education of Young Children, 2005). These methods often are characterized as authentic assessments because they occur during everyday activities and allow the child to demonstrate

knowledge and skills without creating an artificial context that is unfamiliar to the child and may influence performance. Observations, language samples, and interviews are considered authentic assessment methods because no specific set of correct responses is predetermined. Observations and insights from other staff members who speak the child’s home language and have frequent contact with the child can also be collected through questionnaires or family interviews.

The DRDP (California Department of Education, 2015b) described above is a standardized observational instrument that is aligned with the state of California’s Early Learning and Development Foundations and addresses the cultural and linguistic diversity of the state. The instrument includes eight domains of development that reflect the continuum of development from birth to early kindergarten. Most important, all ECE providers are trained in the use of the tool, its implementation, and how to interpret and apply its results to plan instruction.

As discussed by Espinosa and García (2012), many states are designing assessments administered during the first months of kindergarten that will provide data on children’s “readiness” for formal schooling, as well as identify service gaps in the state’s ECE system and guide linguistically and culturally appropriate instruction in the primary grades. These kindergarten entry assessments (KEAs) must be aligned with the state’s early learning and development standards (ELDSs) and cover all domains of school readiness. They also must be linguistically and culturally appropriate, valid, and reliable for the population of children to be assessed, including DLLs. These KEA requirements present challenges for assessment of the school readiness of DLLs. Most states’ ELDSs were designed using the typical development of monolingual English speakers as the norm against which all students are compared (Espinosa and Calderon, 2015); therefore, the language and conceptual development of DLLs is likely to be misinterpreted, underestimated, and inaccurately determined. As states continue to develop and refine their KEAs, they need to address the unique developmental trajectories of young children growing up with more than one language (Espinosa and García, 2012).

ASSESSMENT OF ENGLISH LEARNERS

Assessment of ELs once they have entered the K-12 education system is governed through a complex set of laws and policies created to protect the civil rights of ELs’ national origin status (Title XI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Equal Educational Opportunities Act of 1974), as well as federal funding to enhance their academic outcomes through ESSA. In the context of these laws and policies, assessment is required for the following purposes of accountability:

- initial identification of ELs as they enter school to determine whether they are an EL and therefore qualify for targeted services, such as English language development or bilingual education;

- annual monitoring of student progress in English language proficiency (ELP) and decision making about exiting their status as an EL; and

- annual monitoring of their academic achievement in content areas in certain grades, with a primary focus on literacy and math and a secondary focus on science and other content areas.

Assessment of English Language Proficiency

The assessment of student ELP became universal after the Lau v. Nichols Supreme Court decision of 1974, requiring the identification of students who had limited English proficiency. Early tests, such as the Bilingual Syntax Measure (BSM) and the Language Assessment Scales (LAS), were focused primarily on English vocabulary and grammar and were used solely for purposes of identification and reclassification. ELP assessment became standards-based and administered annually through Title III of the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act of 2001, when states were required to administer annually ELP assessments aligned with ELP standards of the state in the domains of listening, speaking, reading, and writing. Additionally, the law mandated that the ELP standards be aligned with the state’s academic standards.

The state ELP assessment was to be used for Title III accountability through annual reporting by districts of year-to-year progress across proficiency levels (AMAO1) and the percentage of ELs who attained proficient status in the assessment (AMAO2). The requirement of alignment with the academic standards was interpreted as meeting the same academic assessment targets as those required for Title I—a provision known as Adequate Yearly Progress, which history now shows was not met by most education systems.

Under ESSA, and earlier NCLB Improving America’s School Act (IASA) versions of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), mandated ELP assessments must measure students’ proficiency in the areas of speaking, listening, reading, and writing appropriate to their age and grade level. A measure of students’ ability to comprehend English was also added as a requirement, with the possibility that this measure could be derived based on students’ oral comprehension and reading scores. While all states are required to include the foregoing measures of ELP, under ESSA and earlier versions of the ESEA, they have been at liberty to operationalize these five measures of ELP based on definitions of underlying language skills as they judge best based on their individual state or state consortium interpretation

of the research literature on English language development and professional literature on best practices in instruction of English in classrooms. Unfortunately, as noted in Chapter 6, there is no single coherent underlying theory of ELP with a strong basis in validated research at this time. While construction and validation of a comprehensive theory of ELP germane to the use of English for academic learning purposes and relevant ELP assessment is not yet at hand, important progress is being made, as discussed later in this chapter. A key step in guiding this process is the efforts of national teams of EL researchers and state and urban professional organizations that have banded together to begin to build common understandings of how to integrate EL demographic data, data from ELP and achievement assessments, and other achievement-related data systematically to provide a theoretical and empirical basis for sound and effective instruction of ELs.

Following the implementation of NCLB, two consortia of states—World Class Instructional Design and Assessment (WIDA) and English Language Development Assessment (ELDA)—were formed to develop common ELP assessments. States with larger EL populations (California, Florida, New York, Texas) developed their own assessments. The development of these assessments reflected increased concern for measuring English proficiency relevant to the learning of school subject matter associated with mastery of academic learning standards, complicating their purpose as assessment instruments. Significantly, these new-generation assessments of English for classroom learning purposes include attention to some of the key discourse-level skills outlined in Chapter 6 that need to be considered in developing a coherent theory of language proficiency applied to school learning.

Over the past two decades, there has been considerable variability across and within states in the identification, assessment, and reclassification of ELs (e.g., Abedi, 2008; Bailey and Carroll, 2015; Boals et al., 2015; Hauck et al., 2016). Linquanti and Cook (2013) provide a framework for a common definition of ELs and ELP assessment adapted from the National Research Council (2011) report Allocating Federal Funds for State Programs for English Language Learners, which helps frame current concerns in a coherent manner tied to establishing the validity of EL assessments. This framework includes four stages: (1) identify—determine whether a student is a potential EL; (2) classify—verify that the student is EL or non-EL; (3) establish ELP performance standards—ascertain a performance standard with which a language proficiency assessment can be compared; and (4) reclassify—monitor students’ ELP until they meet the ELP performance standard, at which point students may be considered non-EL.

Language assessment for ELs in K-12 settings focuses on the assessment of English, but assessment of academic literacy in the home language is also useful. Oral language assessment of children’s native language may lead to

erroneous identification (MacSwan and Mahoney, 2008; MacSwan and Rolstad, 2006; MacSwan et al., 2002). For instance, while the Language Assessment Scales-Oral (LAS-O) Español and the Idea Proficiency Test I-Oral (IPT) Spanish—both assessments of children’s home language proficiency—identified 74 percent and 90 percent, respectively, of Spanish-speaking ELs as limited speakers of their first language, only 2 percent of participants had unexpectedly high morphological error rates on a natural language sample (n = 145) (MacSwan and Rolstad, 2006). Doubts raised by this work led one large school district to abandon native language assessment (Thompson, 2015).

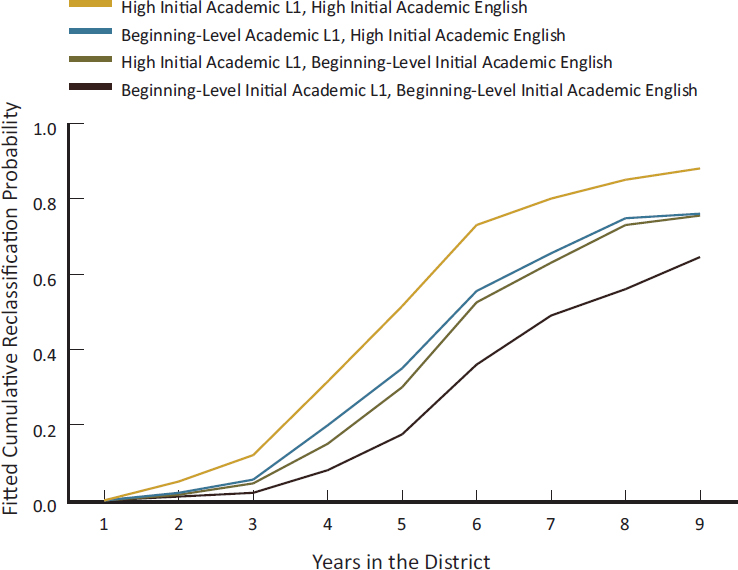

Thompson (2015) analyzed results of Los Angeles Unified School District’s proficiency assessment of language and literacy in the student’s native language as well as the district’s proficiency expectations in English, and similarly found large numbers of children identified as “nonproficient” in their home language. However, the author notes that the native language assessments were designed specifically to measure students’ proficiency in the “language used in academic settings,” as well as school-based literacy. Thompson found that the assessment results were useful for predicting a window for a high probability of reclassification for ELs (see Figure 11-1). Noting concerns about the validity of oral language assessments, Thompson concludes that assessments of children’s home language may play a useful role “if we frame the results not as providing information about what students lack, but as providing information about the resources students bring to the classroom,” rather than serving as a measure of their language proficiency across all contexts (p. 29). In other words, variation in assessment of home language literacy is a strong predictor of subsequent academic outcomes, such as reclassification.

Therefore, it is important to obtain an accurate assessment of an EL’s language development and instructional needs by examining skills in both languages. Federal law requires the assessment of ELP upon school entry. The addition of assessment of the home language, particularly those skills related to academic literacy skills, provides further valuable information about the expected developmental pathway of the student that can be used for targeted instructional services and program placement. For school-age children, it is important for home language assessment to focus specifically on the measurement of academic literacy and the language of school.

Major Changes in ESSA for English Language Proficiency

The largest change in ESSA regarding ELP assessment is its use for Title I accountability as one of the major elements that must be included in the state-developed school indicator system. Previously, ELP assessment was used to monitor districts receiving Title III funding. The ELP assessment is

NOTE: The graph shows fitted results for students who entered the district in 2001-2002.

SOURCE: Thompson (2015).

now a required part of Title I school (not district) accountability. This shift is bringing significant system attention to the ELP assessment, since Title I addresses all students, not just ELs. While Title I regulations were being developed as this report was being written, it is clear that whatever mechanisms each state uses to ensure the quality of Title I academic assessments through its peer review process will apply in significant measure to the ELP assessment now that it is part of Title I accountability.3

Another change in ESSA is the requirement in Title III for standardized statewide entrance and exit procedures for identifying ELs.4 As noted above, there is considerable variation not just across states but often across

___________________

3 A summary of EL assessment final regulations as of early 2017 under ESSA can be found at https://www2.ed.gov/policy/elsec/leg/essa/essaassessmentfactsheet1207.pdf [February 23, 2017].

4 For relevant ESSA Title III Non-Regulatory Guidance, see https://www2.ed.gov/policy/elsec/leg/essa/essatitleiiiguidenglishlearners92016.pdf [February 23, 2017].

districts within states in the procedures and criteria used for EL identification and exiting (Cook and Linquanti, 2015; Linquanti and Cook, 2015; Linquanti et al., 2016). Under ESSA, ELs’ entry into and exit from services will need to be consistent at least within states, thus allowing educators to better serve students with high rates of mobility and making the definition of an EL consistent across the state. Importantly, and as specified in ESSA, states and local education agencies (LEAs) are responsible for establishing the validity of ELP assessments consistent with technical approaches for establishing the validity and reliability of assessments and with professional standards for assessments. The latter are exemplified by the AERA/APA/NCME standards. The formulation and implementation of states’ and LEAs’ validity plans under ESSA will merit the careful attention of education stakeholders and will require significant planning and analysis of the resources needed to maintain consistency with the specifications of the AERA/APA/NCME standards.

The Problem of Initial Identification as a High-Stakes Process

The initial identification of ELs pursuant to ESSA and in tandem with each state’s education code and requirements of the U.S. Office of Civil Rights is a central matter. Initial identification of prospective ELs, including the administration of either a screener or the full ELP assessment, must occur within 30 days of school enrollment. The committee notes that this is a high-stakes assessment because it determines services to be provided to the student. In most cases, moreover, this high-stakes decision is based on a single assessment, often administered when the student enters school in kindergarten or 1st grade and in practice even prior to the start of the school year during the registration period.

An unfortunate chain of events can affect ELs in K-12 schools when their oral home language ability is assessed without due concern for the appropriateness of the assessment instrument and systematic consideration of observational data on language use. Some research has found that such children may be identified as nonproficient in their home language because it is not assessed with valid measures and procedures (Commins and Miramontes, 1989; Escamilla, 2006; MacSwan and Mahoney, 2008; MacSwan and Rolstad, 2006; MacSwan et al., 2002). Indeed, doubts raised by this work led one large school district to abandon native language assessment (Thompson, 2015). It is well known that children identified as “non-non’s” (nonproficient in both English and Spanish) have a higher likelihood of identification in special education (Artiles et al., 2005), even though the specific instruments used to identify them as non-non’s are known to assess their proficiency incorrectly (MacSwan et al., 2002; MacSwan and Mahoney, 2008; MacSwan and Rolstad, 2006).

As a bottom line, the AERA/APA/NCME guidelines advise against the use of a single test for high-stakes decisions. Emerging research on the consequences of initial classification as well as reclassification decisions based on analysis of the discontinuity effects of cut scores shows long-term influences of such decisions on educational outcomes, and therefore high-stakes consequences for students (Robinson-Cimpian et al., 2016).

Reclassification of ELs

Provisions in ESSA Title I raise concerns about the reclassification of students from EL to non-EL status. This is also is a high-stakes decision for states and their LEAs with consequences for students. As described in Chapter 2, under ESSA Title I, states are required to devise and implement EL accountability models that not only identify ELs based on their performance on ELP assessments but also monitor their growth in English proficiency over time, along with their readiness to exit/transition from EL to non-EL status. Simultaneously, as part of their Title I accountability plans, states and LEAs are required to monitor ELs’ academic progress and mastery of ambitious academic standards based on content achievement assessments and state-identified supplemental indicators of academic learning readiness and progress.

ESSA also requires that both states and LEAs implement validation strategies and provide empirical evidence regarding whether they are making suitable progress toward attaining accountability goals regarding transitioning of ELs at a pace and with success rates set by state plans. The AERA/APA/NCME testing standards (American Educational Research Association et al., 2014) are cited as appropriate for this purpose, although these standards were developed primarily with assessments in mind and not for validation of broad systems of indicators suitable for educational evaluation studies. Nonetheless, the standards make a scientifically sound case for consideration of additional empirical validation evidence provided by construct-relevant indicators.

The high-stakes demands on states and their LEAs described above operate at the aggregate EL level within state and LEA jurisdictions, but they also have high-stakes consequences for individual students and their classrooms and teachers by default. Beyond making sound decisions to transition ELs in the aggregate, the aspirations and intent of ESSA are clearly to support states and LEAs in implementing ELs’ transition to non-EL status using decision systems with validity at the individual student and classroom levels.

One of the key findings of the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO) report cited earlier (Linquanti and Cook, 2015) is that states show considerable variation in how they implement decision systems for

reclassifying ELs as non-ELs. The decision to reclassify ELs carries with it the implication that they are now sufficiently proficient in English that they can learn in English and master the academic content required by a state’s mandated academic standards without additional supports. The CCSSO report notes that as of 2015, all states required students to attain or exceed mandated compensatory or conjunctive performance levels on a state ELP assessment to be eligible for reclassification. However, 29 states and the District of Columbia used only an overall composite or pattern of language modality domain scores on a state ELP test as the basis for the reclassification decision. The remaining 21 states relied on an additional one to three supplemental indicators to make this decision. Additional indicators mandated by each state’s education laws included performance on content achievement tests, teacher clinical input or evaluation, and other (such as parental input). Importantly, these 21 states varied in how uniformly and consistently these supplemental indicators were implemented. ESSA attempts to remedy this latter situation by mandating that states adopt and implement policies that ensure a uniform procedure for specifying and weighting such indicators across LEAs within the state. As noted in the CCSSO report, variation across states in such procedures and in the English proficiency assessments used remains an issue. Without a national standard for reclassification decisions, understanding ELs’ progress across states is problematic.

The CCSSO report (Linquanti and Cook, 2015) offers nine state and LEA stakeholder recommendations for improving the validity and utility of EL reclassification decision systems (see Box 11-1). The scientific soundness of these recommendations and their contribution to establishing the validity of reclassification systems are open questions that deserve attention.

Three of the recommendations in Box 11-1 (4, 5, and 9) are worthy of further attention in this chapter because they represent innovative practices in the assessment field. These recommendations are of special importance as resources that can support the validation of classroom-based assessments of ELs’ readiness to transition to non-EL status and monitoring of potential English language learning needs associated with earlier EL status that remain after students are reclassified. The bottom line is the need to know how to interpret ongoing evidence from large-scale ELP assessments, large-scale content and supplemental assessments, and local teacher-based and observation protocols to improve teachers’ and LEAs’ confidence that ELs are ready to function linguistically and academically with sufficient fluency to attain demanding academic standards with proper learning supports. Such information is also critical for identifying continuing English language services needed to support reclassified students’ subsequent learning in English.

Assessment of Academic Achievement

Since the 1994 reauthorization of ESEA (known as IASA), there has been statutory language about the inclusion of ELs in the academic assessments administered to all students. This language states that ELs “shall be assessed in a valid and reliable manner and provided appropriate accommodations on assessments administered to such students under this paragraph, including, to the extent practicable, assessments in the language and form most likely to yield accurate data on what such students know and can do in academic content areas, until such students have achieved English language proficiency.”5

ESSA requires states to adopt challenging academic standards tied to assessments of proficiency in language arts/reading and mathematics administered annually in grades 3-8 and once in high school. An assessment in science at least once in elementary, middle, and high school also is still required. ESSA requires that, effective in 2017-2018, states must evaluate the progress of students on state assessments of reading/English language arts and content areas based on academic standards and models for progress determined by the states, not the federal government. As noted previously, ESSA allows states to design progress and status models that go beyond annual summative assessment results to include interim benchmark assessments measuring growth, and also to include alternative measures and indicators of students’ progress and attainment of standards. This is a key difference from NCLB, which required that all states adopt annual yearly progress models based on large-scale assessments that evaluated students’ progress toward 100 percent proficiency in reading/English language arts and in math and science.

Researchers and national professional groups have expressed concern about the validity and reliability of mandatory large-scale standardized tests for assessing ELs (see Abedi and Gándara, 2006; Abedi and Linquanti 2012; Durán, 2008; Kopriva, 2008; Solano-Flores, 2016; Young, 2009). Questions also have been raised as to whether and how these tests can improve classroom instruction and be based on more comprehensive assessment systems for ELs—important leading-edge research topics (e.g., Kopriva et al., 2016).

___________________

5 Although this language has been in ESEA since the act’s 1994 authorization in IASA, its broad parameters have resulted in its being implemented differently across reauthorizations. With computer-administered assessments, the availability of native language supports has broadened considerably.

Assessment Accommodations

Assessment accommodations have been investigated and implemented as a means of helping to address the concerns noted above. These accomodations can include linguistic modifications of test items to reduce ELP requirements, use of dictionaries or glossaries explaining construct-irrelevant terms found in assessment items, use of side-by-side English and first language presentations of assessment items, oral translations of instructions, oral reading of entire items in an EL’s home language, figural and pictoral representations of item information, extended assessment time, and assessment in small groups (Burr et al., 2015; Durán, 2008; Lane and Levanthal, 2015; Solano-Flores et al., 2014).

Although accommodations are allowed, there are no widely accepted guidelines on which to use and under what circumstances, although preliminary work on such guidelines has been pursued (Rivera et al., 2008). Currently, accommodations are used inconsistently across states (Clewell et al., 2007). Also, it appears that not all accommodations are equally useful. Abedi and colleagues (2006) examined the achievement results of ELs under different conditions of accommodation. They found that ELs’ performance increased by 10-20 percent on many tests when the language of test items was modified, sometimes just by simplification (Abedi and Lord, 2001), but that translating items and using a glossary without providing additional time did not lead to measureably higher achievement. The National Research Council (2011) also produced a comprehensive review of research and issues in this area, with a focus on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) as well as other large-scale achievement assessments.

More recently, Kieffer and colleagues (2012) conducted a quantitative synthesis of research on the effectiveness and validity of test accommodations for ELs in large-scale assessments, an update of a previous synthesis published in 2006 (Francis et al., 2006; see also Burr et al., 2015; Lane and Leventhal, 2015). Based on that updated synthesis, the following recommendations constitute basic guidelines for assessment practitioners:

- Use simplified English in test design, and remove extraneous language demands.

- Provide English dictionaries/glossaries.

- Match the language of tests and accommodations to the language of instruction.

- Provide extended time, or use untimed tests.

Assessment in a Non-English Language

Assessment of content or subject matter learning in students’ non-English first language is another strategy that has been actively investigated (Sireci, 2005; Sireci et al., 2016; Solano-Flores, 2012; Solano-Flores et al., 2002; Stansfield, 2003; Turkan and Oliveri, 2014). Most of this work has pursued translation of English-version test items into students’ home languages. Research has found that it is highly challenging to produce translated assessment items and whole assessments that are psychometrically equivalent to their English counterparts. Nonetheless, states and counties with a need to develop and administer compatible assessments in more than one language in an academic domain have undertaken research to establish the validity of using carefully translated versions of assessments in two or more languages. The results of this research have been inconsistent. Some studies have found evidence that translated assessments do not measure target skills and knowledge as similarly and accurately as would be desired. Others have found that in isolated instances and with relaxed psychometric assumptions regarding the equivalence of assessments, academic content assessments in two languages with highly similar item content can behave comparably in terms of relative item difficulty and association with other academic measures among bilingual examinees with sufficient proficiency in the assessment’s language (Sireci et al., 2016).

Assessment of content in students’ non-English first language remains a prominent option under ESSA. However, as states develop and implement such assessments, they are obliged to develop reliability and validity arguments for their use that meet the Standards for Educational and Psychological Tests (American Educational Research Association et al., 2014). An important complication is that if nontranslation strategies are used and independent first language and English content assessments are developed and implemented, the two assessments need to align with the same state academic content standards and performance expectations at the same grade level if students are expected to be capable of the same kinds of learning competencies in classrooms across languages. Another important complication is that non-English first language tests make sense for ELs only if they have received or are currently receiving instruction in content areas in that language, such as in dual language instructional programs.

Assessment Validity and Test Use Responsive to Policies in Educational Practice

Assessments can be valid and reliable only for the particular purpose for which they were developed and are used; assessments that are valid and reliable for one purpose may be invalid or unreliable for other purposes

(National Research Council, 2011). As discussed below, progress toward establishing assessment validity is being made in a number of areas relevant to the characteristics of ELs, but this progress has been slow in other areas. As a result, a major retooling of assessment theory and methods may be needed to develop scientifically robust models for designing and implementing assessments and for establishing assessment validity—particularly with regard to assessments directly serving student instruction and language development.

Challenges are entailed in meeting educational goals for assessments and validating assessments for all students, regardless of background, but especially for ELs because every assessment is in part a language assessment (American Educational Research Association et al., 1999). ELs’ performance on an assessment always reflects both their ability to understand the language of the assessment and their ability to generate expected responses to assessment tasks and items in the languages permitted for responses (Basterra et al., 2011; Solano-Flores, 2016).

While the use of assessment in education has traditionally been linked to policy, the nature of that linkage can vary. As mentioned elsewhere in this report, there is a growing movement to make assessment relevant to instruction and the instructional needs of students on a day-to-day and even moment-to-moment basis (Bailey and Heritage, 2008; Darling-Hammond et al., 2014; Gottlieb, 2016; Heritage et al., 2015; Jiao and Lissitz, 2015; Pryor and Crossouard, 2005). These more immediate instructional purposes for assessments are quite varied and differ from the large-scale accountability purposes related LEA and state accountability. In the latter case, the focus is on aggregate grade-, LEA-, and state-level assessment results regarding what ELs know and can do in relation to broad educational policy goals and the performance of ELs compared with other subgroups of students. Assessments can be designed and implemented in many ways to impact the everyday instruction of ELs, but three broad possibilities have emerged that point to needed validation research: (1) benchmark or interim assessments, (2) formative assessments, and (3) integrated data analytic assessment systems incorporating the first two assessment types along with other indicators of student learning status and capabilities.

Benchmark or interim assessments aligned with annual state summative assessments of achievement are being introduced by large-scale assessment developers and states. The potential value of these assessments in supporting student learning is mentioned in ESSA. These assessments can be administered periodically before administration of an annual summative assessment to gauge students’ progress toward meeting state academic standards at a grade level. Their results can be used by LEAs, schools, and classroom teachers to determine the readiness of ELs and other students to master skills and knowledge that may appear on the summative annual

assessments. They provide actionable information that can inform ongoing instruction or instructional interventions designed to support students’ mastery of targeted skills and content knowledge where there is evidence of need at the classroom and individual student levels.

Instructionally relevant formative assessments can be constructed by local practitioners and administered as stand-alone performance assessments (Abedi, 2010) tied to current instruction, or they can be embedded in ongoing day-to-day instruction in a manner that is sensitive to instructional goals and the language and background characteristics of individual ELs and other students. Such formative assessments are sociocognitively sensitive (Mislevy and Durán, 2014); that is, they can be designed to be sensitive to students’ background knowledge related to an instructional domain, prior instructional experiences, and evidence of progress in learning complex academic language skills (Bailey and Heritage, 2014; Heritage et al., 2015). Such assessments are not as easily developed as standard large-scale accountability assessments, but they are now being investigated and are encouraged under ESSA.

Finally, integrated data analytic assessment systems can guide instruction of ELs by drawing on complex data systems and an assessment approach known as evidence-centered design. A concrete example of such a system is the ONPAR assessment of science and math content instruction and mastery (Kopriva et al., 2016). This approach builds on carefully constructed models of academic content learning tasks and their performance requirements that the assessments can measure in the everyday instructional context as students develop greater skills and proficiency in a content domain. These assessments can be used to assess what ELs know and can do through computerized assessment tasks that present ELs with multimodal (e.g., textual, visual/figural) information and forms of responding tailored to their individual needs and preferences. Similar work is aimed at uncovering the deep idiosyncratic but systematic features of science tasks administered to ELs that capture fine-grained diagnostic information on how students actually interpret the meaning and performance demands of the tasks (Noble et al., 2014).

Many of these emerging developments are captured by Solano-Flores (2016) with an eye toward future research needed for a more fine-grained understanding of what ELs know and can do and importantly, as with formative assessments, what they might be able to do next toward mastery of content and domain knowledge given their language proficiency (Bailey and Heritage, 2014). They all represent key future directions for improving EL assessment and its practical value tied to both policy and instructional objectives.

The Centrality of Assessment Literacy

Understanding the purpose, design goals, implementation practices, and performance demands of assessments of ELs and the reported performance of ELs on the assessments requires assessment literacy on the part of all educational stakeholders. These diverse stakeholders include not only teachers and students themselves but also parents and community members, educational policy makers, assessment developers, teacher educators, and workforce development stakeholders. There has been as yet no systematic analysis of how to address the full range of educational needs of these different constituencies.

Important beginnings for such efforts do exist in the form of current assessment practices aligned with general policy goals for schooling (see, e.g., Koretz [2008] with regard to educational testing as a whole and Bastera et al. [2011] in the case of ELs). But more such work is needed. As assessments of ELs become more complex and ambitious with respect to what they can reveal about what students know and can do, it is important to keep in mind principles regarding the relationships among any assessment, the target actions and behaviors in the real world, and the language demands the assessment is intended to reflect. In this regard, the work of Bachman and Palmer (2010) remains seminal. It is essential for all stakeholders to appreciate that functioning competently in the face of the sociocognitive and sociocultural demands of the world is a proper focus for assessment beyond evidence of competence in the performance of assessment tasks in and of themselves.

CONCLUSIONS

Conclusion 11-1: To conduct an accurate assessment of the developmental status and instructional needs of dual language learners/English learners, it is necessary to examine their skills in both English and their home language. During the first 5 years of life, infants, toddlers, and preschoolers require developmental screening, observation, and ongoing assessment in both languages to support planning for individualized interactions and activities that will support their optimal development.

Conclusion 11-2: When used for developmental screening for dual language learners/English learners with potential disabilities, effective assessments use multiple measures and sources of information, involve consultation with a multidisciplinary team that includes bilingual experts, collect information over time, and include family members as informants.

Conclusion 11-3: Given state-established standards for progress toward college and career readiness, as well as toward meeting standards for English language development in schools, it is essential to consider the validity of English language proficiency (ELP) assessments for determining English learners’ readiness for exiting services. Validity evidence is required to demonstrate that an ELP assessment appropriately measures the expected academic language demands of the classroom.

Conclusion 11-4: The appropriate use of assessment tools and practices, as well as the communication of assessment results to families and decision makers, requires that all stakeholders be capable of understanding and interpreting the results of academic assessments administered to English learners in English or their home language, as well as English language proficiency assessments. Collaboration among states, professional organizations, researchers, and other stakeholders to develop common assessment frameworks and assessments is advancing progress toward this end.

Conclusion 11-5: Exposure to subject matter instruction in English learners’ first languages is critical to the validity of assessments conducted in that language. Consistent with civil rights law and Every Student Succeeds Act, research supports the use of non-English content assessments in place of English-version assessments for English learners who have been instructed in their home language. The non-English assessments are valid only if they have been carefully constructed to measure the same content and skills and to demonstrate empirically adequate psychometric consistency relative to their English-version counterparts.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abedi, J. (2008). Classification system for English language learners: Issues and recommendations. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 27(3), 17-31.

Abedi, J. (2010). Performance Assessments for English Language Learners. Stanford, CA: Stanford University, Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education.

Abedi, J., and Gándara, P. (2006). Performance of English language learners as a subgroup in large-scale assessment: Interaction of research and policy. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 25(4), 36-46.

Abedi, J., and Linquanti, R. (2012). Issues and Opportunities in Improving the Quality of Large Scale Assessment Systems for English Language Learners. Paper presented at the Understanding Language Conference, Stanford, CA.

Abedi, J., and Lord, C. (2001). The language factor in mathematics tests. Applied Measurement in Education, 14(3), 219-234.

Abedi, J., Courtney, M., Leon, S., Kao, J., and Azzam, T. (2006). English Language Learners and Math Achievement: A Study of Opportunity to Learn and Language Accommodation. CSE Report 702. Los Angeles: University of California, Center for the Study of Evaluation/National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, and Student Testing.

Ackerman, D.J., and Tazi, Z. (2015). Enhancing young Hispanic dual language learners’ achievement: Exploring strategies and addressing challenges. ETS Research Report Series, 2015(1), 1-39.

American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, and National Council on Measurement in Education. (1999). Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing (1999 Edition). Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association.

American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, and National Council on Measurement in Education. (2014). Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing. Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association.

Artiles, A.J., Rueda, R., Salazar, J.J., and Higareda, I. (2005). Within-group diversity in minority disproportionate representation: English language learners in urban school districts. Exceptional Children, 71(3), 283.

August, D., and Shanahan, T. (2006). Developing Literacy in Second-Language Learners: Report of the National Literacy Panel on Language Minority Children and Youth. Executive Summary. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Bachman, L., and Palmer, A. (2010). Language Assessment in Practice. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Bailey, A.L., and Carroll, P.E. (2015). Assessment of English language learners in the era of new academic content standards. Review of Research in Education, 39(1), 253-294.

Bailey, A.L., and Heritage, M. (2008). Formative Assessment for Literacy, Grades K-6: Building Reading and Academic Language Skills across the Curriculum. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage/Corwin Press.

Bailey, A.L., and Heritage, M. (2014). The role of language learning progressions in improved instruction and assessment of English language learners. TESOL Quarterly, 48(3), 480-506.

Bandel, E., Atkins-Burnett, S., Castro, D.C., Wulsin, C.S., and Putman, M. (2012). Examining the Use of Language and Literacy Assessments with Young Dual Language Learners. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina, Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, Center for Early Care and Education Research—Dual Language Learners.

Barrueco, S., Lopez, M., Ong, C., and Lozano, P. (2012). Assessing Spanish–English Bilingual Preschoolers: A Guide to Best Approaches and Measures. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

Basterra, M.D.R., Trumbull, E., and Solano-Flores, G. (2011). Cultural Validity in Assessment: Addressing Linguistic and Cultural Diversity. New York: Routledge.

Boals, T., Kenyon, D.M., Blair, A., Cranley, M.E., Wilmes, C., and Wright, L.J. (2015). Transformation in K–12 English language proficiency assessment: Changing contexts, changing constructs. Review of Research in Education, 39(1), 122-164.

Brassard, M.R., and Boehm, A.E. (2007). Preschool Assessment Principles and Practices. New York: Guilford Press.

Burr, E., Haas, E., and Ferriere, K. (2015). Identifying and Supporting English Learner Students with Learning Disabilities: Key Issues in the Literature and State Practice. REL 2015-086. Washington, DC: Regional Educational Laboratory West.

California Department of Education. (2012). Desired Results Developmental Profile: School Readiness (DRDP-SR). Sacramento: California Department of Education. Available: http://www.drdpk.org [December 2016].

California Department of Education. (2015a). A Developmental Continuum from Early Infancy to Kindergarten Entry: Infant/Toddler View. Sacramento: California Department of Education.

California Department of Education. (2015b). Desired Results Developmental Profile. Sacramento: California Department of Education. Available: http://www.cde.ca.gov/sp/cd/ci/drdpforms.asp [December 2016].

Capps, R., Fix, M.E., Murray, J., Ost, J., Passel, J.S., and Herwantoro, S. (2005). The New Demography of America’s Schools: Immigration and the No Child Left Behind Act. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Clewell, B.C., de Cohen, C.C., and Murray, J. (2007). Promise or Peril?: NCLB and the Education of ELL Students. Washington DC: Urban Institute.

Commins, N.L., and Miramontes, O.B. (1989). Perceived and actual linguistic competence: A descriptive study of four low-achieving Hispanic bilingual students. American Educational Research Journal, 26(4), 443-472.

Cook, H.G., and Linquanti, R. (2015). Strengthening Policies and Practices for the Initial Classification of English Learners: Insights from a National Working Session. Washington, DC: Council of Chief State School Officers.

Daily, S., Burkhauser, M., and Halle, T. (2010). A review of school readiness practices in the states: Early learning guidelines and assessments. Child Trends, 1(3), 1-12.

Darling-Hammond, L., Wilhoit, G., and Pittenger, L. (2014). Accountability for college and career readiness: Developing a new paradigm. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 22(86), 1-38.

Durán, R.P. (2008). Assessing English language learners’ achievement In J. Green, A. Luke, and G. Kelly (Eds.), Review of Research in Education (vol. 32, pp. 292-327). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Escamilla, K. (2006). Semilingualism applied to the literacy behaviors of Spanish-speaking emerging bilinguals: Bi-illiteracy or emerging biliteracy? Teachers College Record, 108(11), 2329-2353.

Espinosa, L.M. (2007). English-language learners as they enter school. In R. Pianta, M. Cox, and K. Snow (Eds.), School Readiness and the Transition to Kindergarten in the Era of Accountability (pp. 175-196). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

Espinosa, L.M. (2008). Challenging Common Myths about Young English-Language Learners. Policy Brief No. 8. New York: Foundation for Child Development.

Espinosa, L.M., and Calderon, M. (2015). State Early Learning and Development Standards/Guidelines, Policies & Related Practices. Boston, MA: Build Initiative.

Espinosa, L.M., and García, E. (2012). Developmental Assessment of Young Dual Language Learners with a Focus on Kindergarten Entry Assessment: Implications for State Policies. Working Paper No. 1: Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina, FPG Child Development Institute, Center for Early Care and Education Research-Dual Language Learners.

Espinosa, L.M., and Gutiérrez-Clellen, V. (2013). Assessment of young dual language learners in preschool. In F. Ong and J. McLean (Eds.), California’s Best Practices for Dual Language Learners: Research Overview Papers (pp. 172-208). Sacramento, CA: Governor’s State Advisory Council on Early Learning and Care.

Espinosa, L.M., and López, M.L. (2007). Assessment Considerations for Young English Language Learners across Different Levels of Accountability. Washington, DC: Pew Charitable Trusts.

Francis, D.J., Rivera, M., Lesaux, N.K., Kieffer, M.J., and Rivera, H. (2006). Practical Guidelines for the Education of English Language Learners: Research-Based Recommendations for the Use of Accommodations in Large-Scale Assessments. Portsmouth, NH: Center on Instruction.

Fuligni, A.S., Guerra, A.W., Nelson, D., and Fuligni, A. (2013). Early Child Care Use among Low-Income Latino Families: Amount, Type, and Stability Vary According to Bilingual Status. The Complex Picture of Child Care Use and Dual-Language Learners: Diversity of Families and Children’s Experiences over Time. Paper presented at the Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, Seattle, WA.

Fuller, B., Bein, E., Kim, Y., and Rabe-Hesketh, S. (2015). Differing cognitive trajectories of Mexican American toddlers: The role of class, nativity, and maternal practices. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 1-31.

García, E., Lawton, K., and Diniz de Figueiredo, E.H. (2010). The Education of English Language Learners in Arizona: A Legacy of Persisting Achievement Gaps in a Restrictive Language Policy Climate. Los Angeles: Civil Rights Project, University of California, Los Angeles.

Gottlieb, M. (2016). Assessing English Language Learners: Bridges to Educational Equity: Connecting Academic Language Proficiency to Student Achievement. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Greenspan, S.I., and Meisels, S.J. (1996). Toward a new vision of developmental assessment of infants and young children. In S.J. Meisels and E. Fenichel (Eds.), New Visions for the Developmental Assessment of Infants and Young Children (pp. 11-26). Washington, DC: Zero To Three.

Gutiérrez-Clellen, V.F. (1999). Language choice in intervention with bilingual children. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 8(4), 291-302.

Gutiérrez-Clellen, V.F., Restrepo, M.A., and Simon-Cereijido, G. (2006). Evaluating the discriminate accuracy of a grammatical measure with Spanish-speaking children. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research, 49, 1209-1223.

Gutiérrez-Clellen, V.F, Simon-Cereijido, G., and Sweet, M. (2012). Predictors of second language acquisition in Latino children with specific language impairment. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 21(1), 64-77.

Hammer, C.S., Scarpino, S., and Davison, M.D. (2011). Beginning with language: Spanish–English bilingual preschoolers’ early literacy development. In D. Dickinson and S. Neuman (Eds.), Handbook on Research in Early Literacy (Vol. 3). New York: Guilford Publications.

Hauck, M.C., Wolf, M.K., and Mislevy, R. (2013). Creating a Next-Generation System of K–12 English Learner (EL) Language Proficiency Assessments. Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service.

Hauck, M.C., Wolf, M.K., and Mislevy, R. (2016). Creating a Next-Generation System of K–12 English Learner Language Proficiency Assessments. RR-16-06. Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service.

Heritage, M., Walqui, A., and Linquanti, R. (2015). English Language Learners and the New Standards Developing Language, Content Knowledge, and Analytical Practices in the Classroom. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Hernandez, D. (2006). Young Hispanic Children in the U.S.: A Demographic Portrait Based on Census 2000. Report to the National Task Force on Early Childhood Education for Hispanics. Tempe: Arizona State University.

Illinois Department of Education. (2013). Early Language Development Standards. Available: https://www.wida.us/standards/EarlyYears.aspx [December 2016].

Jiao, H., and Lissitz, R.W. (2015). The Next Generation of Testing: Common Core Standards, Smarter-Balanced, PARCC, and the Nationwide Testing Movement. Charlotte, NC: Information Age.

Kieffer, M.J., Rivera, M., and Francis, D.J. (2012). Practical Guidelines for the Education of English Language Learners: Research-Based Recommendations for the Use of Accommodations in Large-Scale Assessments. Portsmouth, NH: RMC Research Corporation, Center on Instruction.

Kopriva, R.J. (2008). Improving Testing for English Language Learners. New York: Routledge.

Kopriva, R.J., Thurlow, M.L., Perie, M., Lazarus, S.S., and Clark, A. (2016). Test takers and the validity of score interpretations. Educational Psychologist, 51(1), 108-128.

Koretz, D. (2008). Measuring Up: What Educational Testing Really Tells Us. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Lane, S., and Leventhal, B. (2015). Psychometric challenges in assessing English language learners and students with disabilities. Review of Research in Education, 39(1), 165-214.

Lara, J., Ferrara, S., Calliope, M., Sewell, D., Winter, P., Kopriva, R., Bunch, M., and Joldersma, K. (2007). The English Language Development Assessment (ELDA). In J. Abedi (Ed.), English Language Proficiency Assessment in the Nation: Current Status and Future Practice (pp. 47-60). Davis: University of California.

Linquanti, R., and Cook, G. (2013). Toward a “Common Definition of English Learner”: Guidance for States and State Assessment Consortia in Defining and Addressing Policy and Technical Issues and Options. Washington, DC: Council of Chief State School Officers.

Linquanti, R., and Cook, H.G. (2015). Re-examining Reclassification: Guidance from a National Working Session on Policies and Practices for Exiting Students from English Learner Status. Washington, DC: Council of Chief State School Officers.

Linquanti, R., Cook, H.G., Bailey, A., and MacDonald, R. (2016). Moving Towards a More Common Definition of English Learner, Collected Guidance for States and Multi-State Assessment Consortia. Washington, DC: Council of Chief State School Officers.

López, E. (2012). Common Core State Standards and English Language Learners. Portchester, NY: National Professional Resources.

MacSwan, J., and Mahoney, K. (2008). Academic bias in language testing: A construct validity critique of the IPT I Oral Grades K-6 Spanish Second Edition (IPT Spanish). Journal of Educational Research & Policy Studies, 8(2), 86-101.

MacSwan, J., and Rolstad, K. (2006). How language tests mislead us about children’s abilities: Implications for special education placements. Teachers College Record, 108(11), 2304-2328.

MacSwan, J., Rolstad, K., and Glass, G.V. (2002). Do some school-age children have no language? Some problems of construct validity in the pre-LAS Español. Bilingual Research Journal, 26(2), 395-420.

Meisels, S.J. (1999). Assessing readiness. In R.C. Pianta and M.M. Cox (Eds.), The Transition to Kindergarten (pp. 39-66). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

Meisels, S.J. (2007). No easy answers: Accountability in early childhood. In R.C. Pianta, M.J. Cox, and K. Snow (Eds.), School Readiness, Early Learning, and the Transition to Kindergarten (pp. 31-48). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

Mislevy, R.J., and Durán, R.P. (2014). A sociocognitive perspective on assessing EL students in the age of common core and next generation science standards. TESOL Quarterly, 48(3), 560-585.

National Association for the Education of Young Children. (2005). Screening and Assessment of Young English-Language Learners: Supplement to the NAEYC and NAECS/SDE Joint Position Statement on Early Childhood Curriculum, Assessment, and Program Evaluation. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

National Association for the Education of Young Children and National Association of Early Childhood Specialists in State Departments of Education. (2003). Position Statement: Early Childhood Curriculum, Assessment, and Program Evaluation. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

National Research Council. (2008). Early Childhood Assessment: Why, What, and How. C.E. Snow and S.B. Van Hemel (Eds.). Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Board on Testing and Assessment; Committee on Developmental Outcomes and Assessments for Young Children. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

National Research Council. (2011). Allocating Federal Funds for State Programs for English Language Learners. Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Committee on National Statistics; Board on Testing and Assessment; Panel to Review Alternative Data Sources for the Limited-English Proficiency Allocation Formula under Title III, Part A, Elementary and Secondary Education Act. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Neill, M. (2005). Assessment of ELL Students under NCLB: Problems and Solutions. Available: http://www.fairtest.org/sites/default/files/NCLB_assessing_bilingual_students_0.pdf [December 2016].

Noble, T., Rosebery, A., Suarez, C., Warren, B., and O’Connor, M.C. (2014). Science assessments and English language learners: Validity evidence based on response processes. Applied Measurement in Education, 27(4), 248-260.

Office of Head Start. (2015). Head Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework: Birth to Five. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families.

Paradis, J., Genesee, F., and Crago, M.B. (2011). Dual Language Development and Disorders: A Handbook on Bilingualism and Second Language Learning (2nd ed.). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

Pearson, B.Z. (2002). Narrative competence among monolingual and bilingual school children in Miami. In D.K. Oller and R.E. Eilers (Eds.), Language and Literacy in Bilingual Children (pp. 135-174). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Peña, E.D., and Halle, T.G. (2011). Assessing preschool dual language learners: Traveling a multiforked road. Child Development Perspectives, 5(1), 28-32.

Portes, A., and Rumbaut, R.G. (2014). Immigrant America: A Portrait. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.