2

What Is Character? Moving Beyond Definitional Differences

Although there are many definitions of character, adults can best help young people develop it if they have a clear idea of what it is and what it is not, moderator Richard Lerner commented in introducing a discussion of the nature of character. While “character” is a word with wide application in everyday language, he emphasized, efforts to develop it in young people are focused on something that is “not a trait but a developmental phenomenon.” A person’s character is “not fixed by genes,” he added, but is one outcome of his or her context and experiences. The session began with a synthesis of scholarship on moral reasoning and character presented by Larry Nucci of the University of California, Berkeley, who also proposed a model for understanding the nature of character. Follow-up discussion was anchored by reflections from Robert McGrath of Fairleigh Dickinson University, Kristina Schmid Callina of Tufts University, and Carola Suárez-Orozco of the University of California, Los Angeles.

CHARACTER AS A MULTIFACETED DEVELOPMENTAL SYSTEM

Even skeptics of the idea of character have a sense of what Martin Luther King, Jr., meant when he spoke of looking forward to the day when his “children would not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character,”1 Nucci observed. Though King identified character

___________________

1 Quoted from his speech delivered August 28, 1963; available at https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/king-papers/documents/i-have-dream-address-delivered-march-washington-jobs-and-freedom [November, 2016].

as the central consideration in evaluating an individual, Nucci added, social scientists and educators do not have a shared definition of it, and indeed some have questioned whether the idea of character has value as a subject of research. Nucci provided a review of past critiques and analysis of the idea of character and proposed his own framework for thinking about character, which synthesizes elements from this diverse literature. In his view, character is best understood as a multifaceted developmental system rather than a set of traits a person might have. He suggested an approach for both studying and assessing character that draws on multiple analytical methods.

Critiques of Traditional Views of Character

Traditional understandings of character have often consisted of a set of qualities—such as honesty, fairness, and compassion—that are defined in a particular cultural context as worth developing in young people, Nucci noted. Lists of traditional virtues are often linked to religious or philosophical traditions but generally lack coherence as definitions, and primarily reflect social mores rather than any rigorous conceptual framework, Nucci explained. Psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg belittled this approach to defining character as no more than identifying a “bag of virtues,” he added (Kohlberg and Mayer, 1972). Moreover, there are many candidates for a list of key virtues, and formal lists developed by educators and others may have very little overlap (Lapsely, 1996).

Nucci observed that current lines of research could be described as offering an updated bag of virtues, as the list of recent character-related studies in Table 2-1 suggests. In the same vein, Nucci added, the John Templeton Foundation, a leading funder of character-related work, looks for projects that promote a set of qualities that include “awe, creativity, curiosity, diligence, entrepreneurialism, forgiveness, future-mindedness, generosity, gratitude, honesty, humility, joy, love, purpose, reliability, and thrift.”2

Another critique of defining character in terms of virtues is that individuals tend not to demonstrate them consistently, Nucci continued, which undermines the idea that these virtues can be enduring elements of an individual’s character. Studies conducted as early as the 1920s, he noted, demonstrated that people may behave honestly in some contexts and dishonestly in others (Hartshorne and May, 1928).

Kohlberg (1984) proposed a model for understanding character that would be more coherent than the bag of virtues. He argued that, regardless of cultural context, individuals move through stages in their capacity for moral judgment toward an ideal state in which they base their decisions on

___________________

2 See https://www.templeton.org/what-we-fund/core-funding-areas/character-virtue-development [November 2016].

TABLE 2-1 Elements of Character Targeted by Recent Research

| Character Element | Recent Research |

|---|---|

| Gratitude | Emmons, 2009; Tudge, Frietas, and O’Brien, 2015 |

| Hope | Snyder, 2002 |

| Grit | Duckworth, 2016 |

| Compassionate love | Fehr, Sprecher, and Underwood, 2009 |

| Empathy | Gordon, 2005 |

| Mindfulness | Roeser et al., 2014 |

| Awe | Keltner and Haidt, 2003 |

| Purpose | Damon, 2009 |

| Happiness | Seligman, 2004 |

SOURCE: Nucci (2016).

principles of justice and fairness. This idea has also been criticized, Nucci noted, but the idea that human beings share a concern for justice and the welfare of others is still widely accepted. Nucci agreed that the concern is universal and commented that “any meaningful notion of character has to place morality at the center.” Many of the character attributes that have been highlighted in recent research, he explained, such as grit or social and emotional intelligence, might be deployed for either positive or negative goals: These traits contributed to the practical success of the Nazis or members of ISIS, for example. Such traits may be important in the pursuit of personal and social benefits, such as success in school or career, but do not in themselves lead to moral or immoral actions. Performance itself, he added, “is not a sufficient indicator of a person’s character.”

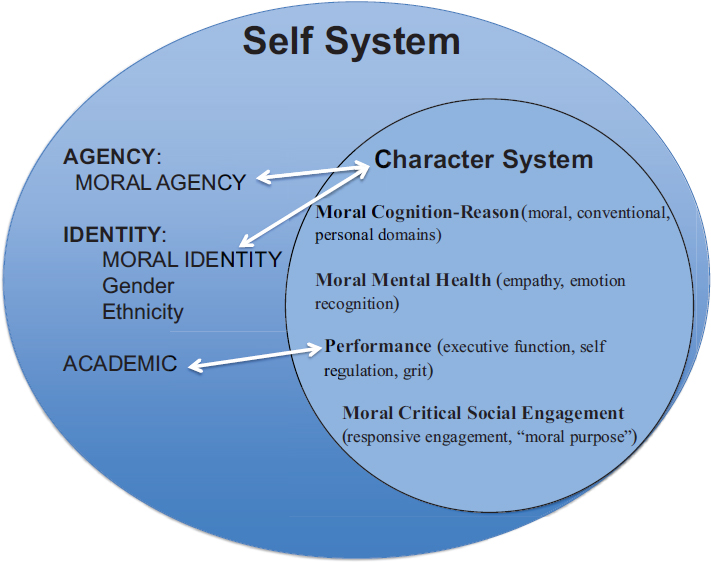

Some researchers who study moral education have moved away from the term “character,” Nucci explained, and use the terms “moral self” or “moral identity” instead. These terms refer not to a set of traits, he explained, but a system that is a component of an individual’s overall sense of self. This overall sense of self includes the individual’s sense of agency, unique personal identity, gender and ethnic identity, and sense of him or herself as a productive member of family and society. The character system that operates within that larger system, he explained, consists of the interactions among elements of the self, such as self-regulation or executive control.

Many scholars of moral education have studied well-known individuals who seem to exemplify moral behavior, on the theory that morality is more central to their sense of self than it is for others. It turns out, however, that a close examination of such individuals’ lives shows that these individuals are not very different from other people, Nucci explained. The behavior

of Thomas Jefferson, who, despite being the author of the Declaration of Independence, fathered several children with his slave Sally Hemings and never granted her freedom, illustrates this point. With the exception of the 1 to 3 percent of the population who are psychopaths, Nucci said, “all people care about morality, and also care about how they view themselves as moral people.” Differences in how central morality is to an individual’s self-identity have not been found to be helpful in explaining differences in behavior, he added.

The idea that people behave morally because it is important to them to be able to “view themselves as moral beings,” Nucci explained, “reduces morality to self-interest” and does not account for people’s judgment about what is a moral choice in a given situation. Other factors play an important part in people’s judgments, he explained, such as their readings of social situations and their capacity to regulate their emotions and social behavior. Indeed, he added, individuals who view their morality as central to their self-identity may veer into moral zealotry.

Character as a Dynamic System

The most useful focus for character development, in Nucci’s view, is moral agency, the capacity to base one’s actions on goals and beliefs about morality. The development of moral agency begins in childhood, he explained, as children make sense of the consequences of their own and others’ actions, and can be disrupted by trauma or violence. Moral agency is not a fixed attribute, Nucci explained, but an element in a complex system of the self that continuously interacts with the other elements, as illustrated in Figure 2-1. Thus character, he noted, is “not a finished product—it is continuously evolving.”

More specifically, Nucci went on, character consists in interactions between an individual and the context: each influences the other. Individuals do not have virtues that exist independent of their choices and actions within particular contexts, and they demonstrate character by behaving coherently across varied situations, rather than consistently displaying a particular trait or set of traits.

Components of the Character System

Based on this understanding, Nucci identified four components (shown in Figure 2-1) of the character system, which in turn is part of the larger self-system:

- moral cognition,

- emotional development or moral mental health,

SOURCE: Nucci (2016).

- performance, and

- moral (critical) social engagement.

The first three components, he noted, correspond to components identified by others (Sokol, Hammond, and Berkowitz, 2010), but he added the fourth in order to include the ways an individual interacts with his or her social context.

Component 1: Moral Cognition

The essence of character is the willful decision to act morally, Nucci observed. Some moral decisions may require little deliberation while others require careful weighing of competing considerations, but they are not accidental or instinctive. Researchers have distinguished moral judgments, which concern issues such as the welfare of others, fairness, or rights, from two other factors that affect decision making: social conventions (norms established by consensus or authority in in a particular social system) and factors related to personal choice and privacy.

Nucci illustrated the distinction between acting according to moral judgment and acting according to convention using an interview with a 4-year-old girl conducted as part of his research; the transcripts are shown in Boxes 2-1 and 2-2. The girl can clearly distinguish between a convention and a moral judgment, he noted.

Nucci and his colleagues have also examined the role of organized religion in moral judgments by interviewing young people and adults from

different faith traditions about their views of moral issues. For example, they asked children from an Amish community in Indiana whether it would be wrong or right to remove a rule prohibiting particular actions. Nearly all the children interviewed reported that it would be wrong to remove rules against actions with a clear moral component, such as stealing or hitting, but significantly fewer reported that it would be wrong to change rules regarding nonmoral issues, such as worshipping on a particular day of the week.

When asked for their reasons, the children were most likely to cite “God’s law,” Nucci explained, as the reason it would be wrong to change rules about moral issues, but they also cited other reasons, such as the welfare of others and fairness. The children were also asked to consider whether their answers would be different if God had not given a rule for either the moral or nonmoral issues. Virtually none of the children responded that the nonmoral rules should be changed, but significant proportions still argued that it would be wrong to change moral rules, such as those against stealing or hitting, even if God had not said anything about these actions. In those cases, the children’s judgments were focused on the impacts of the actions on other people.

Judgments about right and wrong, Nucci concluded, reflect an individual’s capacity to negotiate three domains: the moral, the conventional, and the personal. Each domain puts varying demands on an individual over time, just as an individual’s priorities shift over time. An individual’s priorities are also affected by the facts and information he or she has and the assumptions he or she makes about that information. For example, a person who assumes a human egg is a person may accordingly view abortion as an immoral act of murder, while a person who does not view the egg as a person will disagree. Science, religious belief, and cultural traditions all contribute to such assumptions, Nucci added, and thus critical thinking also plays a part in morality.

Individuals develop in each of the attributes that contribute to moral judgment, Nucci went on, but there are no defined stages of development in people’s capacity to coordinate competing considerations in complex social situations. Nor is there an end point, he added—a stage at which people have the wisdom to apply moral principles in all contexts, regardless of competing nonmoral considerations. In other words, Nucci noted, “moral judgments are inexorably bound up in context, and this makes the assessment of moral growth and the identification of character more challenging.”

Component 2: Emotional Development or Moral Mental Health

Moral mental health, Nucci explained, consists of the capacity for empathy, the ability to accurately read the emotions of others, and a sense

of moral agency. It is these capacities that allow humans to make judgments about what might harm others—and these capacities can be undermined by exposure to a variety of deficiencies or harm in childhood. Educational programs designed to foster children’s capacity for social and emotional learning and to regulate their own behavior, Nucci explained, have often been aimed at overcoming such deficiencies, but these efforts can also optimize moral mental health in all children. Nucci used the term “moral wellness” to convey the idea that maintaining the character system is an ongoing activity rather than a status or state that can be achieved. Nucci noted that social and emotional learning fit in this component because they are essential to moral functioning but do not in themselves lead to moral behaviors.

Component 3: Performance

Character entails not only the capacity to recognize the right thing to do but also “the propensity to act on that judgment,” Nucci explained. Doing the right thing often comes at a cost, he went on, and in some cases the cost may be so high that it is completely rational to “prioritize self-interest over the morally right thing to do.” Nucci cited as an example cases in which child soldiers are ordered to take immoral actions and face dire consequences for refusing to obey. Acting on moral judgments is not simply a matter of willpower or motivation, Nucci argued. Behaving in a moral fashion even when doing so competes with other goals requires a capacity for self-regulation and executive function (the processes that allow people to control their own behavior). Recent work on grit, defined as the capacity to both feel passion for a long-term goal and persevere in pursuing it (Duckworth, 2016), suggests that it may be an important element of the capacity to act morally. For example, grit might help to explain individuals’ commitment to addressing injustices despite extreme challenges, but does not in itself account for the moral thinking that led to that commitment, he noted.

Component 4: Moral (Critical) Social Engagement

The first three components of character describe the development of an individual who will “operate morally in everyday life,” Nucci commented. They do not, however, account for the reality that a person of character might function morally but nevertheless tolerate living within a culture or society that is structurally unequal, or practices, such as slavery, that are immoral. “This is no idle concern,” Nucci added. It would be difficult to support an argument that people who lived during the time slavery was legal in the United States were less moral than people today, he noted, when one considers the injustices and inequality that are tolerated today. At the same time, however, individuals, including children, have across history

and cultural context demonstrated the capacity to critically evaluate moral situations and to resist and protest unfair social practices.

Nucci proposed as the fourth component of character the capacity to take a critical moral stance: to recognize both that one’s own moral perspective may be faulty and that societal norms may be at odds with fairness and respect for human welfare. Most notions of character, Nucci went on, have been focused on the development and functioning of the individual, without explicit regard for the individual’s position within the larger social network. This focus leaves out the impact of sociopolitical factors on the individual’s development, and also the ways in which individuals can bring about social change. Nucci suggested that the capacity to contribute to “principled moral change in the social system” or “civic virtue” is another element of character. This fourth component of character, Nucci observed, may be linked to a sense of purpose, a set of personal goals that give an individual’s life meaning and direction (Damon, 2009), in that such goals often relate to the pursuit of social justice.

Character is not a collection of virtues or traits, Nucci reminded participants, but “a system that enables the person to engage the social world as a moral agent.” Researchers may study particular components of character, he added, but reducing character to any one of them would be an error. The core of it is “morality defined in terms of fairness and human welfare.” Efforts to assess character that center on measuring the degree of a particular trait an individual has, for example, are not useful, he argued. More useful, he suggested, would be to assess the components of the character system—social and emotional learning, moral reasoning, and moral mental health—in much the same way that a physician would assess the various aspects of a child’s physical growth and development. This might be done using questionnaires, interviews, and observations, Nucci suggested, but he also noted that further developments in understanding of moral development and moral functioning in a social context would be needed for such approaches to be practical.

Nucci used a quotation from Theodore Roosevelt to emphasize the vital importance of this work: “To educate a man [person] in mind and not in morals is to educate a menace to society.”

PERSPECTIVES ON PSYCHOLOGY, CONTEXT, AND CULTURE

Three presenters who reflected different academic traditions were asked to respond to Nucci’s paper.

A Positive Psychology Perspective

Robert McGrath said he was particularly struck by one point in Nucci’s argument: that virtue, like the concepts of race and gender, is primarily

TABLE 2-2 Alternative Lists of Key Virtues

| Plato | Aristotle | Jainism | Catholicism | Ben Franklin | G. E. Moore |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Courage |

Courage |

Forgiveness |

Wisdom |

Temperance |

Interpersonal enjoyment |

|

Justice |

Temperance |

Humility |

Fortitude |

Silence |

Aesthetic enjoyment |

|

Prudence |

Generosity |

Straightforwardness |

Temperance |

Order |

|

| Temperance |

Philanthropy |

Purity |

Justice |

Resolution |

|

|

Magnanimity |

Truthfulness |

Faith |

Frugality |

||

|

Honor |

Self-Restraint |

Hope |

Industry |

||

|

Gentleness |

Penance |

Love |

Sincerity |

||

|

Friendliness |

Renunciation |

Justice |

|||

|

Truthfulness |

Nonattachment |

Moderation |

|||

|

Wit |

Celibacy |

Cleanliness |

|||

|

Justice |

Tranquility |

||||

|

Knowledge |

Chastity |

||||

|

Art |

Humility |

||||

|

Prudence |

|||||

|

Intuition |

|||||

|

Wisdom |

SOURCE: McGrath (2016).

a social construction.3 He agrees, he commented, with the idea that all psychosocial concepts are to some extent social constructions. Certainly there is strong evidence, he added, that categories of race are entirely social constructions. Regarding both gender and virtue, however, he suggested, there are more questions. Ideas about gender have changed dramatically in the past few decades, he observed, noting that the Commission on Human Rights in New York City, which investigates claims of gender discrimination, now recognizes more than 30 gender identities. However, in his view, though the concepts of “man” and “woman” reflect shifting cultural ideas and expectations, they seem also to reflect something inherent and essential. Similarly, he believes it is important to consider whether virtue is purely a

___________________

3 Nucci had included this point in an earlier draft of his paper, which McGrath used in planning his remarks, but did not include it in his presentation.

| Erik Erikson | Comte-Sponville | John Templeton | William Bennett | Cawley et al. | Dahlsgaard et al. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Hope |

Politeness |

Creativity |

Self-discipline |

Empathy |

Wisdom and knowledge |

|

Will |

Fidelity |

Curiosity |

Compassion |

Order |

Courage |

|

Purpose |

Prudence |

Diligence |

Responsibility |

Resourcefulness |

Humanity |

|

Competence |

Temperance |

Entrepreneurialism |

Friendship |

Serenity |

Justice |

|

Fidelity |

Courage |

Forgiveness |

Work |

Temperance |

|

|

Love |

Justice |

Future-mindedness |

Courage |

Transcendence |

|

|

Care |

Generosity |

Generosity |

Perseverance |

||

|

Wisdom |

Compassion |

Honesty |

Honesty |

||

|

Mercy |

Humility |

Loyalty |

|||

|

Gratitude |

Joy |

Faith |

|||

|

Humility |

Love |

||||

|

Simplicity |

Purpose |

||||

|

Tolerance |

Reliability |

||||

|

Purity |

Thrift |

||||

|

Gentleness |

|||||

|

Good Faith |

|||||

|

Humor |

|||||

|

Love |

construction or whether there is an objective and universal truth that underlies its structure, even though it is socially malleable.

McGrath showed his own compilation of lists of virtues—see Table 2-2—agreeing with Nucci that such lists have “been all over the place.” His list—a sampling of virtues identified by philosophers from Plato and Aristotle to writers who are alive today—is by no means complete, he added. Philosopher David Hume, for example, listed more than 70 virtues and said there could be thousands more. Another philosopher, Daniel Russell, referred to the challenge of identifying key virtues as “the enumeration problem.” The fact that people through history have made up their own long lists, and that many virtues—such as courtesy or piety—clearly reflect particular times and places, seem to be evidence for viewing character as a social construction, McGrath commented.

There are several reasons not to accept that position, in McGrath’s view. First, if character is no more than a product of cultural context, then

there is no logical way to critique the “bag of virtues” construction—there would be no conceptual framework to replace it. Second, if ideas of character and virtue are entirely socially constructed, virtue education would be no more than a method for convincing people to comply with whichever social conventions have priority in a particular time and place. Third, a purely convention-based list of virtues could be expanded indefinitely. “If one purpose of a virtue list is to provide guidance for personal growth, the longer the list, the less useful it is,” McGrath pointed out.

McGrath offered his perspective on the essential nature of character, which he believes complements Nucci’s arguments well. Figure 2-2 shows

SOURCE: http://www.viacharacter.org/www/Character-Strengths/VIA-Classification# {March 2017].

TABLE 2-3 Parallels Among Competencies

| Competency | Character.org and Thomas J. Sergiovanni | Competency Clusters for the 21st Century (National Research Council, 2012) | Key Competencies in Youth (Park et al., 2016) | In “The Wizard of Oz” |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caring | Heart | Interpersonal | Interpersonal | Heart (Tin Woodman) |

| Inquisitiveness | Head | Cognitive | Intellectual | Brain (Scarecrow) |

| Self-Control | Hand | Intrapersonal | Intrapersonal | Courage (Cowardly Lion) |

SOURCE: McGrath (2016).

the VIA Classification of Strengths and Virtues, developed by the VIA Institute on Character, a nonprofit organization.4 The model, McGrath explained, is based on research in positive psychology and is an effort to develop a comprehensive picture of character.5 The model identifies six universal virtues, shown in the left-hand column, and 24 strengths that everyone has in some degree.

McGrath has studied these 24 character strengths with the goal of understanding the relationship between abstract principles of a well-lived life and elements of character. He has used factor analysis and other statistical techniques to try to identify a set of key strengths, or constructs. He acknowledged that the set would not be definitive but hoped to use these methods to better understand the underlying principles that are essential in character. Questionnaires about the 24 strengths are available on the VIA website and have been completed by millions of adults and adolescents located around the world. He and his colleagues have examined samples of these responses. Three factors—caring, inquisitiveness, and self-control—emerged as meaningful to people across these samples. While other terms could have been used for these three values, they correspond closely to strengths or competencies identified in other contexts, as the examples in Table 2-3 illustrate.

___________________

4 The model is based on the book Character Strengths and Virtues (Peterson and Seligman, 2004). See also http://www.viacharacter.org/www/Character-Strengths/VIA-Classification# [December 2016].

5 Positive psychology refers to “the study of the strengths and virtues that enable individuals, communities, and organizations to thrive” (see http://www.positivepsychologyinstitute.com.au/what_is_positive_psychology.html [December 2016]).

McGrath believes there are strong reasons for viewing these three strengths as essential or universal virtues, but he also acknowledged the importance of social context, which continually redefines what is meant by these essential virtues. For example, both the invention of the printing press and the development of the Internet brought radically new contexts for human inquisitiveness. McGrath suggested that these three strengths are necessary elements of character but not sufficient. Virtues and strengths interact, he said, noting that this idea goes back at least to Aristotle, who argued that people who have the wisdom to develop one virtue logically therefore possess other virtues (this is the thesis of “reciprocity of virtue”). Character education that focuses on only one virtue or strength, however important, is insufficient, in his view. In teaching people about virtue, he concluded, “we need to recognize that people have personal, interpersonal, and cultural values and that together these three contribute to a life well lived.” In his view, effective character development must include teaching young people to “be caring without the expectation of benefit, to be questioning without a crisis, and to be disciplined without structure.”

Studying the Interactions Between Character and Context

Kristina Schmid Callina drew on her experience with research in developmental psychology focused on positive youth development to offer observations about how character can be developed. Her work has been based in a relational developmental systems theoretical perspective, she explained. The premise of this research perspective is that in order to understand any developmental phenomenon, including character, it is important to recognize the reciprocal influences that individuals and their contexts have on one another.

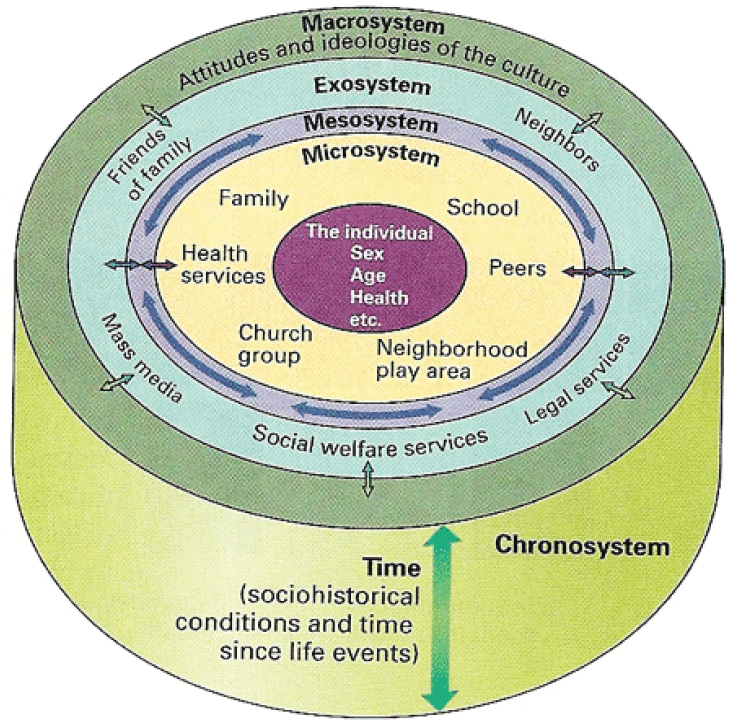

The relational developmental systems perspective moves beyond the idea of “nature versus nurture,” Schmid Callina explained. Instead of weighing the respective influences of an individual’s inherent nature and the experiences he or she has from birth, researchers posit that development cannot be reduced to any one causal explanation—to particular traits or socialization experiences. The relational developmental systems perspective provides a holistic way to understand character development as an element in a complex developmental system like that represented in the bio-ecological model developed by Urie Bronfenbrenner (1979), shown in Figure 2-3.

What does this mean for the study of character? Character is contextually defined, Schmid Callina said. It is a function of the continuous mutually reinforcing relationship between the individual and his or her context. She agreed with the idea Nucci had expressed in his paper, that a notion of character as a set of virtues that might “exist independent of their enactment in a particular context [is] meaningless (p. 9).” Any assessment of character

SOURCE: Santrock (2007).

must account in some way for the interactions between the person and the context, she added.

Across time and place, good character reflects the coherence of an individual’s behavior—how reliably he or she displays “the right virtue, in the right amount, at the right time,” in Aristotle’s words. The attributes needed might vary according to circumstances, Schmid Callina noted, so what is critical is coherence, not consistency. Focusing on the idea that character traits are fixed, or on the importance of single traits, will likely prevent one from seeing the coherence in an individual’s actions.

Schmid Callina described a study of character and leadership development among cadets at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, called

Project Arete, to illustrate how ideas about the importance of context and coherence can be used to evaluate character development. The most common method of evaluating character development curricula, she noted, has been to assess particular strengths in young people and then compare their scores from before and after completing the program. This approach often fails to integrate the idea of coherence.

Specifically, such evaluations examine average group differences on particular character attributes, rather than the individual’s relationship with the developmental system, Schmid Callina explained. They do not examine the individual’s developmental pathways or interactions with his or her context, which would provide insight about character development. To explore character development among West Point cadets, she explained, one might examine the attributes they bring that make them more likely to develop as leaders of character, or what about the West Point experience influences their character development. These are important, she noted, but to focus just on individual attributes, or on characteristics of the program, as components is to overlook their interactions. More useful, she explained, is to examine which features of the program promote which attributes among cadets at a particular time and place.

One challenge in examining individual pathways to development, she explained, is that standard approaches to statistical analysis in the social sciences tend to focus on differences between people rather than changes within individuals.6 Integration of multiple methods of qualitative and quantitative research is needed, Schmid Callina noted, to effectively analyze changes within individuals and then aggregate such findings to yield broader conclusions about character development. “Person-centered analysis is critical,” she argued for evaluating programs such as that at West Point. There are as many different experiences at West Point as there are cadets, she added, to highlight the importance of using new approaches to understand them. This is a lively area of research, she noted in closing, as many new tools are being developed. Such research is expensive and time consuming, but in her view very promising.

The Influence of Culture and Context on Character Development

Carola Suárez-Orozco brought the perspective of a cultural developmental psychologist to the question of how cultural context influences character development. She said she was struck by the multitude of definitions of character, she noted, because defining culture has posed a similar challenge. In the 1950s, anthropologists Alfred Kroeber and Clyde Kluckoholn

___________________

6 Schmid Callina recommended The End of Average: How We Succeed in a World That Values Sameness by Todd Rose (2015) for a detailed discussion of these issues.

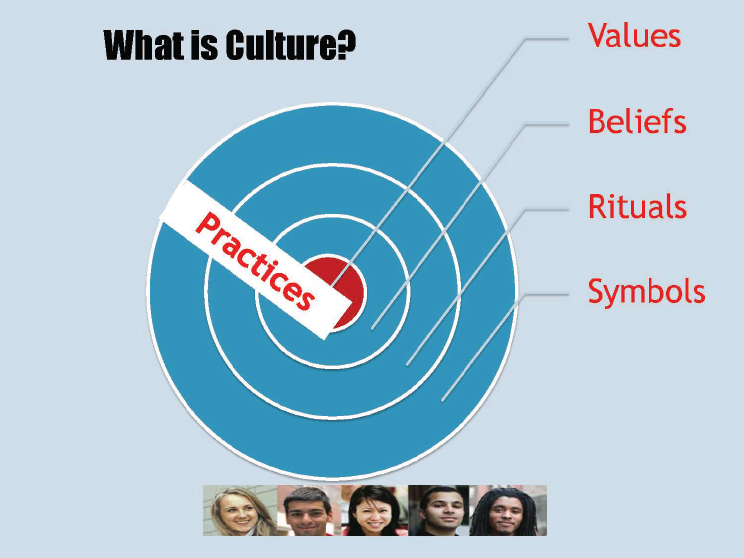

articulated the problem and identified 152 definitions of the term. They synthesized from these many definitions five essentials: values, beliefs, rituals, symbols, and practices. Human values are at the center, Suárez-Orozco explained, as Figure 2-4 illustrates, and each of these elements is expressed through humans’ day-to-day practices.

Anthropologists pay close attention to cultural practices—the routines, activities, and other things that people do—Suárez-Orozco commented. These include

- language use;

- kinship systems;

- religious and ritual practices;

- economic models;

- power structures and hierarchies;

- gender expectations;

- cultural socialization (child rearing);

- dress; and

- food.

SOURCE: Suárez-Orozco (2016).

Anthropologists also focus on cultural models or belief systems people develop. It is through such models that members of a culture generally specify the critical knowledge that is essential in their cultural context, she explained, and individuals who do not acquire this knowledge are “ruled out” as competent members of the group. At the heart of cultural models, as the bullseye in Figure 2-4 illustrates, are values, norms, and ideologies. Cultures have what anthropologists call “distributed knowledge,” shared ideas and information that is developed collectively and helps to define the group. Distributed knowledge is often aligned with religious belief systems, Suárez-Orozco noted, and is passed down across generations.

Describing a culture is complicated because each has multiple layers, Suárez-Orozco explained, and as anthropologist Clifford Geertz said, describing a culture requires “thick descriptions” of symbolic systems and meanings. However, social scientists too often reduce these complexities to simplistic categories, describing a society as either collectivist or individualistic, for example, or speaking in broad terms about nationality (e.g., American versus Chinese) or ethnicity (Latino versus black or white). Even speaking of culture as language, ethnicity, and nationality does not capture the complexity of culture, she observed. But, as John Berry (1997, p. 27) wrote, “There is no contemporary society in which one culture, one language, one religion, one single identity characterizes the whole population.”

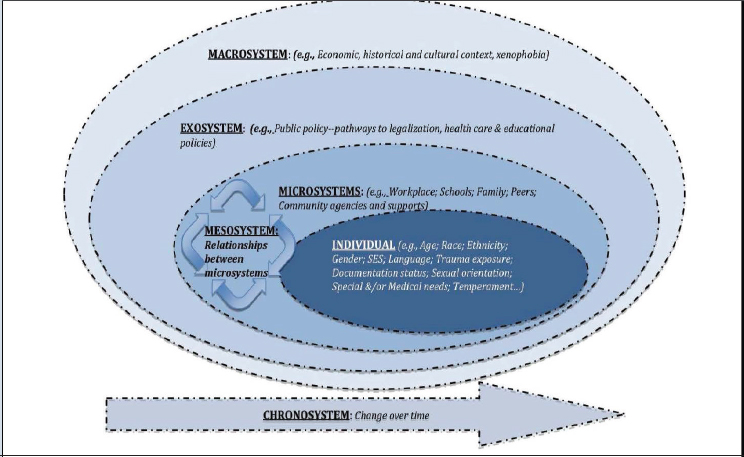

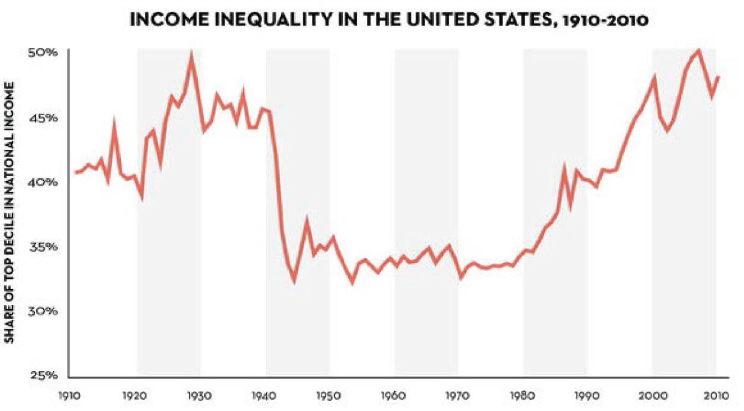

Suárez-Orozco used a simplified version of the Bronfenbrenner model that Schmid Callina had used to show how the experiences of immigrant children illustrate the intersection of culture, values, and character: see Figure 2-5. She noted that the more distal elements—those farther removed from the individual’s daily experience—are often overlooked but are vitally important to character. For example, economic inequality in the United States has grown sharply in the last 20 years, as Figure 2-6 illustrates. More children are living in extreme poverty, she noted, and immigrant children are among those most affected. Moreover, one-quarter of immigrant children are growing up “under the shadow of undocumented status,” she added, and 400,000 people are deported every year, increasing numbers of whom are the parents of children who are U.S. citizens. Xenophobic stereotypes exacerbate the stress that immigrant children face, Suárez-Orozco continued.

Suárez-Orozco offered data from research she has done on the civic participation and social responsibility of young adults of Latino immigrant origins to illustrate how distal factors may influence the development of character (Suárez-Orozco, Hernandez, and Casanova, 2015). Latino youth who are in the first or second generation of their families to live in the United States are the fastest growing group of young adults in the nation, she pointed out (Rumbaut and Komaie, 2010). The degree to which these young adults engage civically will influence the way they develop as indi-

SOURCE: Suárez-Orozco (2016).

SOURCE: Suárez-Orozco (2016).

viduals and also influence U.S. society, she added (Lerner, Dowling, and Anderson, 2003; Stepick, Stepick, and Labissiere, 2008). Suárez-Orozco and her colleagues explored the degree to which these young people follow patterns of civic engagement typical in the broader population, and also sought to understand the values and motivations that drive them to engage civically.

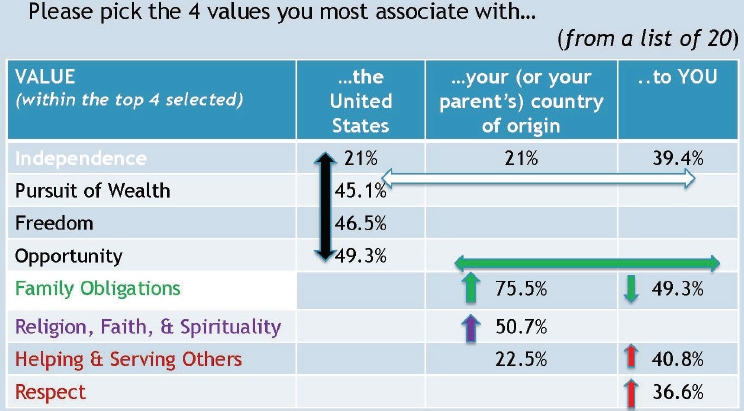

They recruited a sample of 58 young adults of Dominican, Mexican, Guatemalan, and Salvadoran origin who are first- or second-generation immigrants living in cities in the Northeast. The participants were asked to complete questionnaires and to participate in a Q-sort exercise, in which they ranked their views and values. Figure 2-7 summarizes the participants’ responses to the task of picking four values (from among 20) they saw as most associated with the United States, their or their parents’ country of origin, and themselves.

Independence was given a high priority across all three groups, she noted, but some other values were specifically associated with only one or two. For example, pursuit of wealth, freedom, and opportunity were associated with the people of the United States generally, but not the participants’ countries of origin or themselves. The young adults associated religion only with their countries of origin, and highlighted family obligations, helping and serving others, and respect, along with independence, as important to themselves.

SOURCE: Suárez-Orozco (2016).

Suárez-Orozco and her colleagues also examined the ways in which the young people choose to be civically engaged. Many are not especially involved politically, she commented, but many do volunteer, for example, serving as mentors or translators or taking leadership roles in civic efforts such as support for the Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors (DREAM) Act.7 The young adults studied also showed a propensity to select civic-minded professions, Suárez-Orozco noted, such as education, medicine, and the law, and cited the specific goal of giving back to their communities or those in need. Looking across the study participants, she added, two-thirds demonstrated “active levels of civic engagement,” and their primary reasons were a sense of social responsibility and the desire to rectify a social injustice.

“Culture matters,” Suárez-Orozco concluded. The values that are at the core of culture, in her view, are key “drivers of character.” However, understanding the complex relationship between culture and character requires a deep understanding of a particular population developed using multimethod approaches. Context also matters, she added, and it is especially important not to neglect the distal influences.

DISCUSSION

Discussion focused on the “tension between the degree of emphasis placed on the individual versus the cultural context” that was evident in the presentations, as one participant put it. The participant pointed out that, although people are clearly influenced by their cultural environment, “there is a biological substratum and a genetic influence.” People do have an unchangeable core of traits that would persist even if they were transplanted to an entirely new cultural context, he argued.

Nucci responded by acknowledging that each individual does have a unique identity that is stable, but that reducing character to a set of immutable traits is “misguided.” Martin Luther King, Jr., he reminded the group, was both an esteemed moral leader and a “philanderer,” who presumably was dishonest to family members and others to hide his infidelity. Thinking about character in terms of coherence—to attempt to understand how an individual’s internal motivation and reasoning interact with the circumstances and external influences—is more useful for making sense of this type of paradox than looking for consistent traits in the individual, Nucci suggested. “If consistency is the standard, we all fail,” he pointed out.

Others turned the discussion to practical implications for character education. One suggested that focusing on the commitment to be a better

___________________

7 This legislation was first proposed in the United States Senate in 2001 but has not yet passed.

person is a way around the debate over the respective influences of individual attributes and cultural influences. Programs that help young people develop character could usefully be viewed as opportunities for young people to practice acting as people of character, making judgments about what is right and wrong, and making decisions about how to pursue concrete goals, this person suggested.