3

Views of What Works in Developing Character

The discussion turned next to the practical challenges of developing character in young people. Marvin Berkowitz of the University of Missouri, St. Louis, drew from research on school-based character education to identify evidence regarding current strategies and principles to guide educators and program developers. Reed Larson of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Camille Farrington of the University of Chicago, and Karen Pittman of the Forum for Youth Investment provided additional perspectives.

THEMES FROM RESEARCH

Developmental psychology research, Berkowitz noted, suggests that accepted ideas about effective parenting map directly onto ideas about educating for character—and that every teacher is in a sense a surrogate parent. Yet, he suggested, few parents use the sorts of character development strategies, such as reading or posting inspirational quotations, hanging posters bearing a single word such as “respect,” or handing out reward tickets to children “caught” doing something praiseworthy, that are often found in schools and other settings. “If these practices are so effective,” he wondered, “why don’t educators use them with their own children?”

Another way to think about what might be effective in developing character in young people, Berkowitz added, is to consider how one’s own positive character traits actually developed. In contrast to Nucci’s view, he suggested that individuals do have traits such as honesty or being caring that they display consistently, though not perfectly. Most often, he said,

people asked about how their traits developed report that they worked to emulate a parent or other role model, or had determined that they would not have negative traits they saw in their own parents, such as racism or dishonesty. He has never encountered a person who reported that his or her character “came from a curriculum or a set of lessons,” he commented.

Berkowitz defined character as “the complex constellation of psychological characteristics that motivate and enable individuals to function as competent moral agents,” noting that his definition is essentially the same as the one Nucci had used. Character education, in turn, he defines as “a way of being” through which adult educators and role models foster the development of character. People are complex organisms, he noted, and the idea that they can be “taught” to have character does not fit with the models of human psychological and moral functioning that developmental psychologists and other researchers use. The goal of character development programs should not be to teach, but to promote healthy adult cultures and actively foster young people’s development, he said.

Berkowitz and his colleagues identified character development strategies for which there is evidence of effectiveness (Berkowitz at al., 2016). They reviewed research from the past 16 years that has been collected through the What Works in Character Education Project,1 meta-analyses and other recent syntheses of the research, and literature on parenting with respect to character. The researchers looked for reviews of scientific studies focused on the outcomes of character education, defined in terms of moral reasoning, positive psychology, and other frameworks—they did not include effects on academic achievement or other outcomes. They did not analyze implementation strategies, but focused on program design and pedagogical approaches that make a difference.2

Berkowitz developed a structure for thinking about best practices for character education, which he calls PRIME, for prioritizing character education, relationships, intrinsic motivation, modeling, and empowerment. He used PRIME to organize the primary points he drew from the literature review conducted for the workshop.

Prioritization—Character education will not work, in Berkowitz’s view, if it is not an “authentic” priority in the school or setting. He and his colleagues found that several practices were consistently found in programs and set-

___________________

1 See http://character.org/key-topics/what-is-character-education/what-works [December 2016]. Berkowitz noted that he and his colleagues are developing the Character Education Research Clearinghouse (CERCh) to make their findings more widely available. See Berkowitz et al. (2016) for a detailed discussion of the sources for this work.

2 Most of the work they reviewed addressed character education in school settings, but Berkowitz noted the relevance of this work to out-of-school settings, which have received significantly less research attention.

tings that do make character a genuine priority. One is rhetorical emphasis: The adults talk regularly about shared goals and values. Another is allocation of resources, such as investment in professional development. School and classroom climate, particularly a sense that teachers are trusted, is a key element. Treating character education as a school-wide value—rather than confining it to particular lessons or making it the responsibility of a particular teacher—is another way schools and programs demonstrate commitment, as is effective leadership from the principal, he noted.

Relationships—Healthy relationships within and beyond the school are also characteristic of settings where character education is effective, Berkowitz said. Positive relationships flourish when they are “strategically promoted,” he added. In the classroom, this means teachers use interactive pedagogical strategies such as cooperative learning, for example, and teach interpersonal skills. School settings in which relationships among all staff members, families, and community members are respectful and engaged foster character learning. Schools can promote such relationships through structured activities that invite people who do not normally go into classrooms to interact with students, for example.

Intrinsic Motivation—“Children can be partners in the journey of their own character development,” Berkowitz commented, and he said he does not favor behavior-modification strategies for fostering certain behaviors. “We want kids to internalize values and virtues,” he suggested, and that is best done using strategies that engage students’ own motivations. One effective practice is to focus on students’ self-growth, guiding them in setting goals, offering focused training, and allowing them opportunities to review their actions and behavior and initiate changes, he said. Opportunities to serve others also give students the chance to engage in morally positive actions and reflect on what they learn.

Modeling—The adults and older students in exemplary character education settings model core values or virtues and social and emotional competencies, Berkowitz noted, and this has a powerful influence on young people. “What you do has more impact than what you say,” he added.

Empowerment—Schools tend to be very hierarchical, Berkowitz noted. Shared leadership and classrooms run according to democratic principles foster the kind of character program leaders hope their students will develop.

Another set of practices that Berkowitz and his colleagues identified in the literature did not fit neatly into the PRIME model, he noted. He listed these practices in the category of developmental pedagogy, meaning

approaches that are intentionally designed to foster the development of character and social and emotional competence. One method for doing this, he explained, is to directly teach about character, such as by teaching social and emotional competencies or integrating character concepts into a broader curriculum. Another is to set high expectations for growth that are clearly articulated for students but also scaffolded so that incremental progress is recognized. Giving students opportunities to practice the competencies they are learning, for example through role-playing, is also critical, he added.

More scientific research on effective practices is needed, Berkowitz noted, including research that isolates specific practices or compares sets of practices, as well analyses that shed light on effectiveness. Nevertheless, he believes the available literature clearly demonstrates that “we have to teach it and practice it,” in order to foster character development in young people.

PERSPECTIVES ON KEY INGREDIENTS

Reed Larson, Camille Farrington, and Karen Pittman each offered additional thoughts about the features and practices that are critical for programs that aim to foster character development.

Supporting Adolescents

Larson focused on the question of how institutions and caring adults can best support adolescents grappling with the complex contexts in which they live. Aristotle, he pointed out, argued that neither rote repetition nor teaching would prepare a young person to confront a difficult situation, arguing that, “We become just by the practice of just actions, self-controlled by exercising self-control, and courageous by performing acts of courage.” Confronting a genuinely confusing unstructured situation that poses a moral challenge, Larson added, can be a profound learning experience. Larson suggested that after-school programs, especially those for adolescents, provide real-world situations, opportunities, and dilemmas through which young people can practice in the way Aristotle suggested. He referred to this type of learning as “cycles of practice in context.” He noted that his ideas about after-school character education aligned well with Berkowitz’s findings from in-school character education.

Larson has conducted research with 250 youths from different ethnic groups, using multiple interviews to analyze their accounts of their social and emotional learning and character development. This work has identified some “active ingredients” that are especially important to programs for older youth: the opportunity to grapple with challenges, including moral challenges, investment in meaningful goals, and constructive peer processes.

The opportunity to grapple with real-world challenges, in a supportive, prosocial environment with the oversight of trusted program leaders is invaluable for young people, in Larson’s view. There are two ways that programs often provide such opportunities, he explained. One is to engage young people in service projects, political actions, art or video productions, or other long-term, goal-oriented activities that tap into their interests. Another is for a young person to take on a substantive role, for example as a group leader, blogger, board member, dance captain, or camera person. These kinds of roles come with obligations, he observed, and much research in developmental psychology supports the idea that struggling with and fulfilling meaningful obligations can have positive effects for young people.

To illustrate the potential effects of this kind of experience, Larson quoted a girl who cared for a baby pig, preparing to enter it in an agricultural fair. The pig became very sick and its care became very challenging, but the girl explained, “It’s just me. I’m the one that has to push myself to do these things no matter how badly I don’t want to step in that pigpen, I gotta do it, gotta do it.” Larson also described the successful efforts of a group of young people in an action program who challenged discipline policies in their school that they believed were unfair. To be effective, they had to figure out how to communicate effectively with teachers, administrators, fellow students, and the Board of Education, but they eventually succeeded. Interviewed three years later, the students described that struggle as “foundational to their later lives,” Larson said.

Challenges such as these, Larson emphasized, provide opportunities for young people to practice skills, work out moral positions, and see through trial and error what works. Programs that facilitate this kind of learning, he added, “don’t just cultivate a climate, but create a culture of action” that motivates young people and helps them learn. The programs give the young people agency and create an atmosphere of trust, but also provide tools and models that support them in their efforts to overcome challenges in their work.

Voluntary after-school activities are particularly good opportunities for young people to invest their time and energy in goals that are meaningful to them, the second key ingredient discussed by Larson. These are activities that young people are interested in, feel they are good at, and enjoy. They are also activities young people perceive as useful as they pursue life and career goals, and often they are also opportunities for altruism. When students believe that what they are doing may actually make a difference to others, they often have additional motivation to persevere through challenges.

Peers may have negative or positive influences, Larson noted, and afterschool programs can foster constructive peer processes, the third ingredient in effective after-school programs. Indeed, peers are a critical “secret sauce” of after-school programs, he suggested. Adults can foster constructive peer

interactions in a few ways. One is to cultivate a “safe space,” by modeling and encouraging constructive dialogue that incudes reflective discussion, problem solving, and empathy.

Another is to support young people’s individual and collective investment in their work. The roles young people play in the program are important to the development of constructive peer relationships, he noted: they confer both responsibilities and rights and give young people opportunities for agency, the power to pursue an objective. Often, as a program begins, young people take on roles with a lot of enthusiasm and then find the roles more demanding than they expected. They experience self-doubt and emotional strain, and their commitment may waver. At this stage, the adults can help young people persevere with encouragement and guidance. Young people also recognize that they owe it to their peers to persevere, not out of guilt but because they have a shared investment in the outcome. Young people who are part of groups that go through these stages successfully, without giving up, can build character strengths that transfer to other settings, such as home and school, Larson noted.

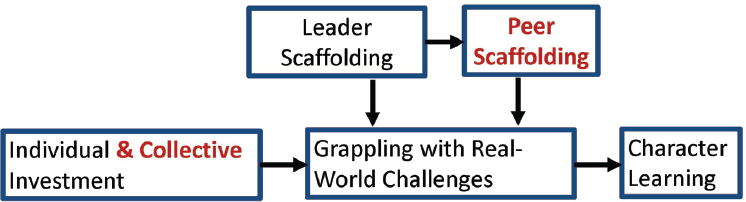

Figure 3-1 illustrates how these elements fit together and reinforce one another in an after-school setting. After-school projects can be structures in which young people develop character voluntarily, Larson concluded. Given the opportunity, young people want and choose to take on challenging projects and roles in the service of something they care about, he added. Adults play a key role in helping to shape the experience of “practicing being an upstanding member of their group,” as Aristotle suggested, Larson noted. He emphasized the value of staff expertise in helping young people experience a sense of agency.

Foundations for Young Adult Success

Camille Farrington offered her perspectives on how young people develop successfully, based on work she has done with colleagues (Nagaoka

SOURCE: Larson (2016).

et al., 2015). As both Nucci and Berkowitz had made clear, she noted, character development entails “a lot of different things happening simultaneously.” She endorsed the framing Berkowitz et al. offered in their paper (2016, p. 19), that “Ultimately the goal of character education is for children and adolescents to become good people, to develop into and act as agents for good in the world. Hence this is about being people of character even more than it is about acting good.”

Random assignment is not a promising strategy for studying a construct this complicated, or the practices that might promote it, Farrington noted. It is difficult to isolate specific strategies in order to study their effects, and much existing research has focused on outcomes other than character itself. Moreover, she noted, researchers are often compelled to use short-term behaviors as proxies for the state of being a person of character, or being on the way to becoming one. Parents and educators use many strategies and practices in the hope that, over many years, their efforts will pay off as the child or student becomes an adult of character, but “there’s no way to be certain at the time that these methods will bear fruit,” she observed.

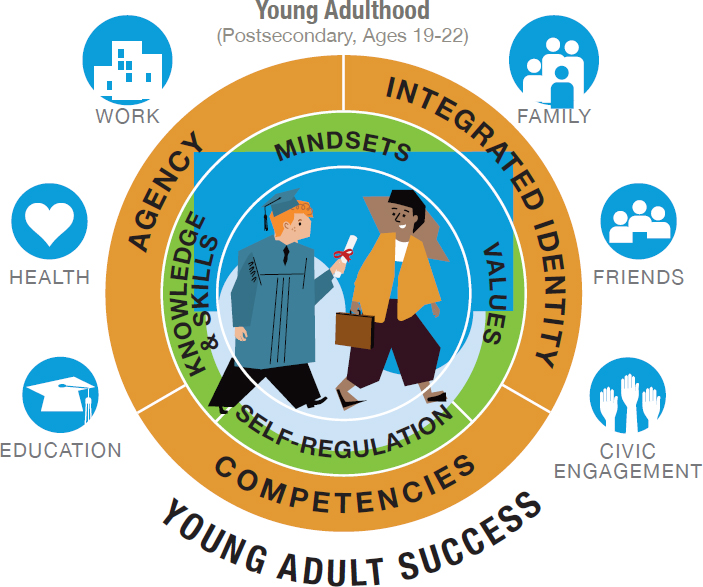

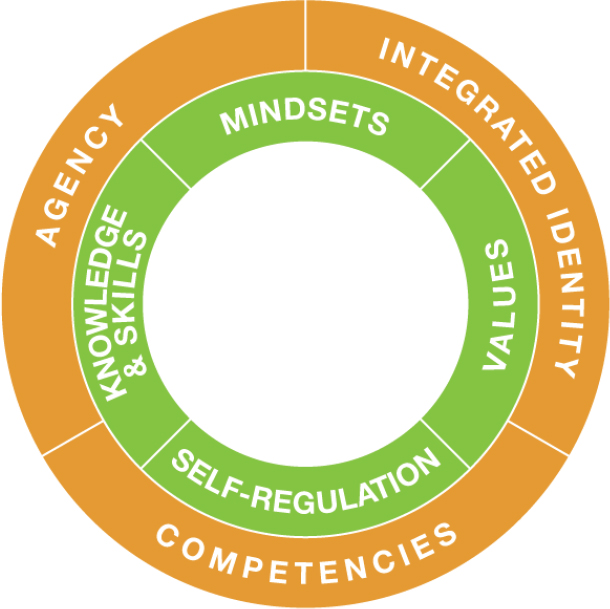

Farrington and her colleagues conducted a study of what matters in the development of successful young people, and how and when they develop the attributes that are important to success. Their research included a review of relevant literature and extensive interviews with experts from fields including neuroscience, developmental psychology, social psychology, education, workforce development, and sociology. They took a broad view of what success means: a balance of positive work, family, civic engagement, and other elements, as shown in Figure 3-2. Figure 3-3 illustrates their view of the foundation that allows young people to develop successfully. The outer rings show the three essential elements young people need to develop by the time they reach adulthood: a sense of agency, an integrated identity, and a set of competencies. (Farrington noted that these elements continue to develop throughout adulthood as well.) The inner ring shows specific components that are the foundation for developing the three essential elements. These elements all contribute to a person’s functioning as an individual (sense of self) and to his or her functioning in the context of family, community, and the broader world, she added.

Farrington and her colleagues used a developmental approach to explore when and how these elements develop. A common research approach, she noted, is to examine the inputs—conditions and practices—that might help to develop character. She and her colleagues hoped to learn about the mechanisms through which these practices result in the development of character, she explained, so they shifted the focus from what adults do to what young people do, “the kinds of experiences they have and how they make meaning of those experiences.”

SOURCE: Nagaoka et al. (2015, p. 4).

The developmental experiences that emerged from their review include both actions and reflections, Farrington explained, as illustrated in Figure 3-4. The five actions on the left side of the figure—such as encountering new modes of behavior, being able to explore in a safe space, and practicing and developing skills—are the opportunities through which young people develop character strengths. Versions of these kinds of experiences are important for children at all stages from early childhood through young adulthood, and are also key for adult learning, Farrington noted. Reflecting on and making meaning of these experiences is just as important, she went on, agreeing with Larsen on this point. Without the opportunity to internalize, or integrate, experiences, as Larsen had noted, the experience can “just fly away, as if it had never happened,” Farrington explained. The five actions shown on the right side of the figure are key ways individuals actively reflect on their experiences. These include describing what one observes, evaluating and making judgments about one’s own and others’

SOURCE: Nagaoka et al. (2015, p. 20).

behavior, making connections both with other people and among ideas and experiences, envisioning the future, and integrating experiences into one’s sense of self.

The role of adults, Farrington concluded, is to provide these opportunities for action and reflection for young people at every stage of their development. “We are very good at helping kids encounter facts and information, and practice skills,” she observed, but “we tend to skip over” most of the others, though they are very important for learning and character development.

Youth Development as a Shared Goal

The focus on practices that can help children and adolescents flourish is very timely from a policy perspective, noted Karen Pittman, because it is “happening not just in school-based and after-school contexts but

SOURCE: Nagaoka et al. (2015, p. 16).

in other systems.” There has been a surge of interest in evidence-based policy, she noted, and it is important for the practice and research communities to “act quickly to broaden the definition of what evidence is and generate new methodologies.” Pittman agreed with Farrington and others who have argued that randomized controlled trials are not a useful research approach for character development. It is important to identify other research designs, she explained, in order to accurately identify what is working. Pittman noted that her organization, the Forum for Youth Investment, has been involved in two recent projects that look across sectors such as child welfare, juvenile justice, and civic education and prevention (see Box 3-1).

Pittman also endorsed the idea of moving away from the “bag of virtues” approach to character, in which a program is designed to develop a particular trait or strength. As many of the presenters had made clear, what is critical is to understand “how all these skill sets and strengths come together” so that a young person grows up with a strong sense of agency and identity, and how program practices create the contexts that contribute to that. “Our job is not just to model moral behavior,” she commented, “but also to nurture it.” The way to do that is to create an environment that is safe in which young people can be challenged and rewarded for their efforts. That only happens in environments in which young people are engaged, she argued: “That is the secret sauce.”

More quantitative research is available in some of the other fields concerned with child and adolescent welfare, Pittman noted, such as juvenile justice. Studies, some of which used a randomized control model, have yielded findings. For example, she noted, “scaring kids doesn’t work, so you can throw out all the programs that are based on that.” This body of work has begun to identify program components and practices that are effective, she added (see Box 3-1). It has been complicated to isolate practices or strategies she noted, because most programs use multiple ones. The programs covered in the What Works Clearinghouse,3 she noted, use an average of eight strategies each and often have their own names for them. The focus of recent juvenile justice research, she explained, has been to use meta-analysis and other techniques to cull out the essential components of the strategies and approaches that are effective. These components, or principles, she added, have been the basis for standard protocols that can be used in program evaluation.

“We can talk about what works,” Pittman continued, but in her view it is more useful to look for “what makes it better.” Improvement comes, she suggested, when there is a complete cycle, or feedback loop. Evidence is used to identify practices with the potential to be effective, these practices are implemented in a program or classroom, and the youth workers

___________________

3 See http://character.org/key-topics/what-is-character-education/what-works [December 2016].

or teachers who are implementing the practice with young people are observed (in a nonthreatening manner) and given feedback about their work. When this happens, she explained, the educators and program leaders can “deconstruct” the practice and use it to sustain improvement.

Pittman also endorsed the importance of developmental pedagogy, as Berkowitz had discussed. She suggested that the key question is whether any given program is aligned with the ideas about how young people develop over time that were articulated across the presentations. The out-of-school literature, she observed, echoes much of what Berkowitz had reported from the in-school literature, and in her view the time is right to merge these. “No matter what system you are working in,” she commented, it will be important to build a culture that supports youth development, and to make sure all staff understand how to implement the practices aimed at doing this and integrate them with other goals of the program.

Pittman closed with the analogy of school as a big jar filled with tennis balls representing the primary teaching objectives it is responsible for, such as algebra, language arts, and social studies. The jar is full: there no room for another tennis ball so adding a requirement for social and emotional learning, or character education, will seem impossible. Instead of viewing those goals as another tennis ball, Pittman suggested, educators should view them as marbles or sand that can be poured into the jar and can fit around the tennis balls. “You may not immediately change what happens within the tennis balls,” she commented, but you begin the process of engaging all the adults in the school in helping young people develop character.