6

Measuring Character

Researchers, programs, organizations, and funders all want trustworthy evidence that young people who are exposed to some form of character education grow or develop as a result of that experience. As the rich debate about how to define the nature of character and goals for character education suggests, however, measuring outcomes in this area is challenging. Noel Card of the University of Connecticut reviewed methodological challenges in the measurement of character and proposed suggestions for addressing them. Discussants Clark McKown of Rush University Medical Center and Nancy Deutsch of the University of Virginia offered two additional perspectives.

METHODOLOGICAL ISSUES

The divide between research and practice is only part of the challenge for improving practice in the development of character and social and emotional learning, explained Card. There is also a gulf between methodology and research and practice, he suggested, and he began with a practical, hands-on overview of how key psychometric principles apply to the study of character development.

Psychometric Fundamentals

Reliability, validity, and equivalence are three fundamental principles of measurement, Card noted, and each presents challenges for the mea-

surement of knowledge, attributes, or skills that can be difficult to define precisely, such as character.

Reliability

Reliability is a measure of how “repeatable” a measure is, or the extent to which scores are consistent when a test of a particular construct is given multiple times, Card explained. There are several ways to think about reliability, and most common is the idea of internal consistency reliability. Typically, test developers want to measure a construct in more than one way, using multiple items or tasks. For example, he commented, a survey or interview might include multiple questions about an aspect of character to “get at it in different ways.” Measures of internal consistency indicate how “repeatable” these different questions are—the degree to which they are measuring the same thing, based on how similar the scores are across the group of questions. Psychometricians tend to “turn up their noses” at this type of reliability, Card explained, because it is based on assumptions about how parallel the questions truly are.

Another measure, test–retest reliability, is an indication of how repeatable the test is across multiple measurement occasions. In this case, the assumption is that the construct itself is stable over a particular time span—so if the time span between testing and retesting is too long it would be possible that any change is accounted for not by the way the measure functions but by actual developments in the person being tested.

A third type of reliability is inter-informant reliability, a measure of how repeatable test results are across multiple individuals who report on the character construct being assessed. In this case, Card explained, the underlying assumption is that the character construct being measured is the same in different contexts in which the reporters observe it. For example, both a classroom teacher and an after-school counselor might be asked to evaluate a child’s character based on observation. If the character construct is stable across the classroom and after-school setting, then any differences in the observations would contribute to a lower inter-informant reliability score.

It is worth noting, Card observed, that “we don’t really know” how stable elements of character may be over time or across different settings. Nevertheless, internal consistency is important. It is also easier to collect evidence about multiple questions within a single test than to collect evidence over time or across settings, so this measure is commonly used in the context of character education. It is important not to overemphasize the value of reliability measures, Card pointed out. All of the measures are estimates from a sample, so they are measures of how a particular testing instrument performs in a particular context at a particular time.

Validity

Validity and equivalence are at least as important as reliability, Card continued. Validity is the extent to which a measurement actually assesses what it is intended to assess. Suppose one wanted to measure how frequently young people were displaying a particular prosocial behavior, and differences among them, Card suggested. The challenge is to find a way to measure the behavior accurately without inadvertently measuring other things that are not relevant. One could use a scale that measures a very specific behavior, such as a questionnaire item asking how often young people offer to help the teacher, but that might not provide enough information, he pointed out. On the other hand, if the construct is not carefully defined the results might reflect the respondents’ understanding that the behavior is socially desirable, rather than how well they display it.

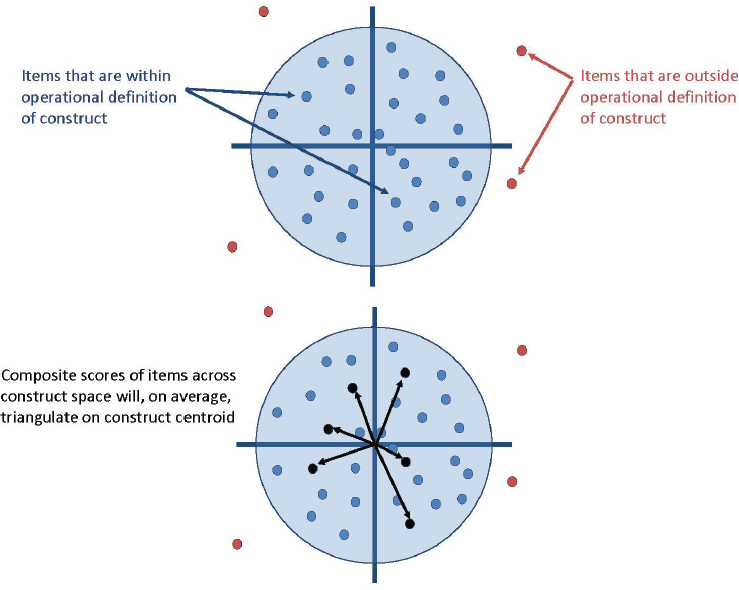

The key to validity, Card emphasized, is to have a very clear definition of the character or development being studied, but the field has not settled that problem. “We have to work toward this,” he suggested, but it is still possible to measure character without either assuming that it is immutable or reducing the complexity of human behavior, psychology, and cognition to a simple variable. What measurement experts can do instead is to define a domain they can measure that represents the traits, skills, or behaviors being studied, as shown in Figure 6-1.

The circumference of the circle represents the boundaries of an operational definition of the construct to be measured, such as a set of behaviors that are characteristic of the prosocial attitude being tested: the dots represent items or questions that sample elements of this domain, perhaps particular behaviors. The dots that lie outside the circle assess behaviors or attitudes that are outside of the defined domain, such as a belief that the teacher favors particular behaviors.

At the center of the circle is the “bullseye,” Card explained—the heart of the construct. Theoretically there could be an infinite number of dots inside the circle, questions that accurately measure some aspect of the domain. The job of the test developer is to identify a practical number of them that, together, provide an accurate composite picture of the domain being tested. The arrows across the bottom circle represent the way a carefully chosen set of items will “triangulate around the bullseye,” Card explained.

The distribution of the dots in Figure 6-1 represents a situation in which there is relatively low internal consistency reliability. If the researcher removes the items that contribute most to this low internal consistency, Card explained, the result might be a set of items that yield highly consistent results but lie at the edge of the circle—not centered around the bullseye. In other words, “efforts to improve reliability might produce a highly

SOURCE: Card (2016).

reliable measure of the wrong thing,” Card emphasized, and this danger is another reason it is so important to have a clear definition of the construct.

Equivalence

The third key psychometric idea is equivalence, Card went on, an indicator that the measurement performs in the same way across groups or time. This idea is useful in assessing test fairness, or differential item functioning, because it is the basis for determining whether a test item performs differently across groups, such as males and females or ethnic groups. That is, an item performs differentially if it yields different results for individuals who in reality have comparable knowledge or skills only because something about the way it is designed favors one individual over the other. Items that are equivalent across time allow researchers to accurately assess changes that result from an intervention, for example. There are three levels of equivalence, Card noted (configural, weak, and strong), but he suggested

that it is rarely tested in the context of character education. Doing so requires specific analytic tools, such as factor analysis or item response theory, that are technically challenging.

Implications for Measuring Character

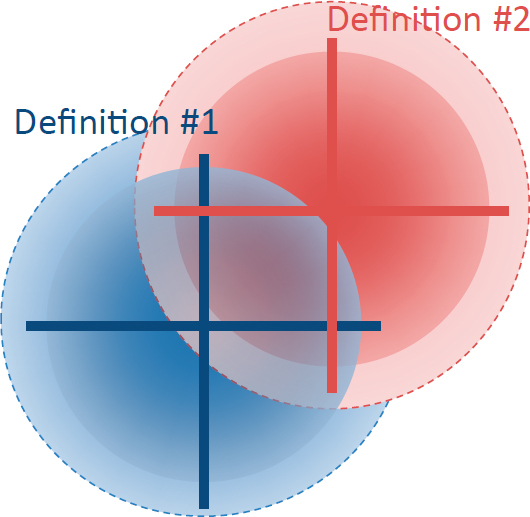

A clear definition of what is to be measured is important for each of these basic psychometric properties, Card commented. In the arena of character, he noted, there are multiple definitions of many constructs, and operational definitions often have “fuzzy boundaries.” This is not a problem in itself but it means that measures or scales might more closely match one definition than another in ways that are difficult to trace. One possible solution is to identify the items that fit more than one definition, as shown in Figure 6-2. It might be possible to more closely align existing definitions so that the overlap would be greater, he suggested. It would not make sense to artificially force this, he added, but whether it could be done in a reasonable, defensible way is a matter “for the field to consider.”

From Card’s perspective, one of the defining features of the field of character development is its diversity. The variation in the nature of programs that do this work and the contexts in which they serve, as well as

SOURCE: Card (2016).

the diversity of the adults and young people involved, is striking. Card suggested that those involved in measurement of character and related constructs should pay greater attention to the possibility that psychometric properties may function differently across diverse populations and contexts. It is important to assess these psychometric properties in every study, he emphasized, and to pay explicit attention to measuring equivalence.

Moreover, a researcher studying the impact of an intervention needs to consider the possibility that other developments that occur at the same time the intervention is implemented may affect the measure. Box 6-1 lists the kinds of errors that can arise when this is not done effectively. The bottom line, Card suggested, is that “we cannot have confidence” that an intervention was effective without establishing that it affected the aspect of character itself, rather than the measurement of it.

Two Examples

Card offered two examples to illustrate these ideas, studies of gratitude and humility that were parts of an ongoing meta-analysis of 11 character strengths he is conducting with colleagues. They reflect two very different situations, he noted. He and his colleagues have found that studies of gratitude all tend to use one of a very small number of measurement instruments. One of these is a six-item questionnaire that was developed through a series of steps. The researchers who developed this test, known as the GQ-6 (McCollough et al., 2002), first administered a much longer set of questions to college undergraduates and then used statistical techniques

to identify the six questions with the highest inter-informant reliability and construct validity.1 They then administered the six-item test to a broader sample of adults and found similar evidence of construct validity.

A second method for measuring gratitude is the Gratitude, Resentment, and Appreciation Test (GRAT) (Watkins et al., 2003). In this case the researchers conducted the psychometric analysis using a 55-item test, which they also administered to college undergraduates. Using statistical analysis they identified the three factors that appeared to be most relevant and used those to winnow the list of test questions. They did not, however, replicate the analysis that identified the three factors, Card noted, though they did test the psychometric properties.

There were limitations to both of these studies, Card pointed out: a possible overemphasis on reliability in the first case, and possible errors in the identification of the relevant factors in the second. His point was not to criticize the researchers in either case—indeed, he noted that both were impressive efforts to translate a theoretical concept into a usable measure. However, both are treated as seminal studies, he commented, and researchers who later adopted these measures are unlikely to have assessed the psychometric decisions for themselves or taken them into account in using the results they obtained using these instruments.

This is not at all uncommon, Card noted: developing sound measures takes time because it is challenging. Even where there are a few seminal papers, he pointed out, “we don’t just put up the victory flag and say ‘done.’” Most instruments need to be modified as theory changes, and to be adapted for use with particular populations and in particular contexts, he added. In the case of gratitude, Card noted, there are actually four popular measures that have been used in a diverse set of studies—findings that emerge across a body of work that uses different methods can yield valuable conclusions.

Researchers of humility, however, do not have a small number of widely used measures to rely on, and many seem to develop their own unique measure, “to be used in that study and never again.” One problem with this situation is that any two studies of humility may actually be measuring very different things. Conversely, other studies may be measuring constructs that are not identified as humility, but which match definitions of it that other people use. Some researchers may develop a measure without adequately testing its psychometric properties, Card added, which may be one reason why so many researchers in this area have chosen not to rely on the previous literature.

___________________

1 There are several categories of validity; construct validity is the type Card had described, a measure of the degree to which an assessment measures what it is intended to measure. In this case, the researchers compared the results to the results of tests of related constructs, such as religiosity.

“It is virtually impossible to synthesize results” from a body of work that has this degree of inconsistency in the measures used, Card pointed out. It is very difficult to say with confidence which programs are effective, or answer other important questions about humility. The situation with gratitude research is preferable, he added, but neither is ideal.

Suggestions

Card closed with a few suggestions with respect to planning studies, reporting results, and accumulating a body of trustworthy research. He challenged participants to include questions about psychometrics in their assessments of available research. It is important to explore what sorts of measures were used to produce compelling results, how they were developed, and what limitations might need to be taken into account. He emphasized that measuring changes in character attributes is not the same as simply measuring that attribute at a particular time.

Card also noted that “We shouldn’t assume that the creator of an instrument has thought about every population and context in which it might be used.” Others who use a measure need not be rigid, he suggested, but should carefully modify it to better suit different circumstances. Pairing a quantitative measure with qualitative or mixed-method studies—possibly working with a multidisciplinary team—is another important strategy for improving the definition of the construct and the associated measure.

Finally, Card observed that full reporting on psychometric properties should be a part of any study, so that readers can fully understand what was done and what possible limitations they should consider. He acknowledged that this is difficult. Some of the analyses are technically demanding, which means time, expertise, and resources are needed to support that extra effort. Studies that include detailed psychometric analysis tend to be less interesting to publishers, he noted, but it is important that this information be available, perhaps as a component of a larger study.

“We need to shift perceptions,” Card suggested, so that people in the field value psychometric analysis and “don’t just view it as a preliminary to more interesting results.” Meta-analysis of a body of research results is an important tool for identifying findings that reflect a much larger sample than any single study could, as well as a more diverse set of study settings and types of measures. Because studies typically differ in many ways, Card noted, it is possible to use statistical procedures to identify causes of some of the differences that emerge from a synthesis of results across a large body of studies. This sort of information can help the planners of future studies to make well-supported decisions about the measures they will use.

Card closed with the point that “if there were easy solutions we would have figured this out long ago.” He pointed out that his focus was on

quantitative measurement of individual differences, and that other kinds of analysis have much to offer as well, including quantitative measures of growth and change and causation; ways to conceptualize individual differences in character; and qualitative and mixed-method approaches.

PERSPECTIVES ON MEASUREMENT CHALLENGES

Pathways Forward for Measurement

The scientific study of character depends on good measures, and Clark McKown highlighted the importance of these issues to both practitioners and researchers. In his view, the work of these two groups should overlap in substantive ways. McKown endorsed Card’s overview of standards of evidence that apply not only to the study of character but also across social science fields, and highlighted a few key points.

First, he noted that Card described constructs in the study of character as having fuzzy boundaries, meaning that it is difficult to draw precise boundaries between one construct to be measured and another. McKown suggested that the problem is broader. Constructs throughout the social sciences share this problem, and it was clearly a theme throughout the workshop, he observed. There is clearly not yet consensus on “what it is we are really after,” he suggested. If any 10 people at the workshop were asked to define character or social and emotional learning, he added, it is likely that they would offer 10 different definitions. Consensus may not be feasible, he acknowledged, but “we need to get our story straight,” because it is essential for measurement.

McKown offered an example of research in an area where the concepts have been clearly defined to illustrate the potential benefits to the “forward momentum” of the study of character that conceptual clarity could bring. He has worked with colleagues to develop a web-based system for measuring social and emotional skills in elementary age students (McKown et al., 2016). They are targeting thinking skills, such as the ability to understand another person’s thoughts and feelings and solve social problems, as well as behavioral skills, such as the ability to join an ongoing group and help someone in need. They are also measuring mental and behavioral components of self-control. McKown and his colleagues made firm decisions about constructs that would and would not be included in their work, which, he argued, allowed them to develop a measurement system that meets the psychometric standards Card described.

The stakes for approaching measurement carefully are high, McKown continued, because “what gets assessed gets addressed.” A common language and metrics are needed, he added, because where the field cannot offer trustworthy evidence, “all we are doing is vulnerable to the winds of trend and fad.”

There is also an urgent need for high-quality assessments that can be used in practice, McKown observed. He suggested that in addition to the construct validity Card discussed, these assessments should also have consequential validity. This type of validity is a measure of the consequences, both intended and unintended, of the way test results are used. (In general, psychometricians do not assess how valid a test itself is, but how valid the interpretations that can be based on test results are for the intended purpose, he noted.)

A real-life example illustrates why this is important, McKown explained. A collaboration among California’s largest school districts, called CORE Districts,2 has included measures of noncognitive skills (e.g., self-efficacy, social awareness, mindsets, and self-management) in their accountability system for schools—an effort McKown said was “bold and important.” However, a public controversy developed over the concern that using measures that are based on self-reports for this sort of high-stakes purpose is not good measurement practice. Reasonable people can disagree about whether the indicators that CORE Districts used provide evidence that is valid basis for accountability decisions, McKown commented, but the situation highlights the importance of consequential validity for all measures of character and social and emotional learning. Consequential validity is not just a matter of technical properties, he added, but also requires consideration of social values.

McKown emphasized the importance of thinking carefully about the purposes of any assessment. In the context of character development, he suggested, the “current state of the art” supports formative assessments, those that are used to identify students’ needs, guide instruction, and give students feedback about their learning. Existing assessment methods are generally suited for use in program evaluation as well. Few current measures, however, have the psychometric properties needed when the results will be used for high-stakes accountability purposes, in his view. More development is needed in this area, he suggested, and it is critical to think about the purpose before, not after, planning an assessment.

McKown’s last point was that “in the best of all worlds, the method of assessment will match what is being assessed.” Social science researchers use surveys, observation, teacher ratings, behavior ratings, and direct assessments, in which children solve problems that assess social, emotional, or behavioral traits or skills. No one of these methods can measure each type of construct well, McKown commented, and each is better suited to measuring some things than others. For example, to assess how well children can read others’ facial expressions, it would be better to use direct assessment in which they look at faces and indicate what they are expressing, than to give

___________________

2 See http://coredistricts.org [December 2016].

them a questionnaire in which they rate their ability to do this. Similarly, asking children about their own behaviors is less useful than asking teachers and others to report on the behaviors they observe.

McKown concluded with the hope that the field is poised to move forward “swiftly and wisely” in developing sound measures of character and social and emotional learning.

Understanding Constructs in Context

Nancy Deutsch framed her comments with the point that “measurement should always serve the goal of making our work in out-of-school time better.” From her perspective as a qualitative and mixed-methods researcher, she noted that two themes struck her repeatedly during the workshop: the socially constructed nature of social science, and the importance of context, variability across time, people, and settings. Qualitative and quantitative researchers, she suggested, both treat these ideas as central but approach them in different ways. They ask different questions, and their questions drive their methods.

Quantitative research is well suited for assessing the presence, amount, and prevalence of constructs related to character, Deutsch observed, and to testing hypotheses about the factors that influence character. Quantitative researchers recognize the importance of variability, she went on, but their methods are not suited to answering questions associated with the variability of social contexts and its implications for understanding character.

Social science researchers focus much of their energy on defining, understanding, and measuring constructs and how interventions might influence them, Deutsch continued, yet they seldom question some of the assumptions that underlie these descriptions of human behaviors and thinking. In particular, researchers rarely “acknowledge that all constructs are social constructions.” Ideas about character that underlie the constructs researchers measure in this field differ across contexts, and this is important to the study and measurement of character, Deutsch commented,

Psychometric principles such as validity and reliability are formal acknowledgments that measurement tools are subject to error, Deutsch continued, yet they also reflect an assumption that “something called character exists as a singular, objective fact.” The measurement challenge is generally understood to be one of getting as close as possible to assessing this true construct, without, in Deutsch’s view, sufficient regard for the social, historical, and political influences on that construct.

The field of psychopathology provides examples to illustrate the social influences on construct definition. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) defined homosexuality as a sociopathic personality disorder until 1973, Deutsch pointed out. By 2009 the DSM’s authors

officially regarded homosexuality as a “normal and positive variation of human sexuality,” she noted, and opposed the use of therapy to “convert” an individual to heterosexuality. Definitions and terminology related to gender and sexuality continue to evolve, she added, reflecting the way people live.

How a construct is defined determines who is understood to have more or less of the desired attribute, and therefore which individuals need intervention, Deutsch explained. Another example of this comes from a study of moral development in the 1950s. Psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg defined six stages of moral development through which people progress, based on research with samples of white men. When women began to be included in follow-up research, however, he and his colleagues found they tended to get “stuck at level 3, a stage that focuses on interpersonal relationships, and not progress to the stages that had been defined as higher.” Psychologist Carol Gilligan later pointed out that by developing the theory based only on male samples, Kohlberg and his colleagues had inadvertently missed important evidence of differences. Gilligan posited that there were essential differences between men and women; research on moral development has pursued further lines of inquiry in this area.

Research on differences in the use of school discipline practices across students in different racial and ethnic groups provides another example of the importance of context, Deutsch observed. For example, some research has shown that approaches to social and emotional learning designed to be neutral may inadvertently reflect misunderstanding of the diverse ways students from marginalized backgrounds express social and emotional skills. Redefining the relevant social and emotional constructs in ways that reflect awareness of conscious and unconscious biases and the role of power and privilege, Deutsch explained, leads to the use of different measures and altered ideas about students’ behavior and need for intervention.

These issues illustrate, in Deutsch’s view, that “researchers and practitioners alike need to be careful about how we define ‘normative’ constructs.” When researchers measure constructs based on the experiences of a narrow subset of people, Deutsch continued, the experiences and expectations of that subset become definitive.

These examples also illustrate the importance of context in measurement, Deutsch observed. The principle of measurement equivalence that Card described is based on the assumption that a construct should be the same across contexts, time, or groups, she noted. If, however, the social ecological theory articulated by Bronfenbrenner, discussed by Schmid Callina and others (see Chapter 2), is correct, that assumption might be false. The question, Deutsch explained, is not whether a person may have a core set of character traits that are consistently displayed, but whether there is an “essential center to the construct itself.” In other words, she noted, people

might define a construct in consistent ways—viewing selfishness as putting self before others, for example—but identify different sorts of behaviors as examples of selfishness, depending on their context.

Quantitative measures of constructs such as character are valuable, Deutsch concluded, but qualitative and mixed-methods approaches are needed to illuminate “meaning as it exists in context.” The strengths of qualitative social science are like those of qualitative analysis in chemistry, which aims to identify the components of a mixture, she noted. In the social sciences, qualitative analysis examines the components of a social setting: the context. Qualitative research can help explain the meaning of outliers and sources of variation that are apparent in quantitative research. Qualitative methods make it possible to explore variations that may be masked by the crisp definitions that are important in quantitative research. For example, racial and ethnic identifiers are used to study possible differences across groups, but they may also mask important differences. People who fall in the categories of black, white, or Latino have origins in many countries and experiences that are too varied for statistical tools to address.

Qualitative methods have sometimes been viewed as useful primarily for exploratory work that can support the development of measures, for example. But in Deutsch’s view, these methods can also help explain developmental pathways and individual changes over time, and answer questions about how and why people behave as they do. Thus, she concluded, “we have many tools in our toolbox” for understanding the broad, complex domain of character.

This page intentionally left blank.