2

Transporting Evidence-Based Preventive Interventions into Communities

In the workshop’s keynote address, Velma McBride Murry, the Lois Autrey Betts chair in education and human development and Joe B. Wyatt distinguished university professor at Vanderbilt University, laid out many of the issues involved in putting prevention science to work in communities to improve the health and well-being of children. In doing so, she introduced many of the topics covered in greater detail later in the workshop, including the need for strong relationships among researchers, program developers, and communities and the need to balance fidelity and adaptation.

AREAS OF CONSENSUS AND TENSION

The integration of evidence-based interventions into communities rests on several critical areas of consensus, Murry said, including the following:

- Principles of community engagement are critical to inform and guide the process.

- Establishing partnerships between community members and researchers is key.

- Feedback from community partners is important.

- Mixed methods (qualitative and quantitative) are needed to test programmatic effects and evaluate adoption and adaptation processes.

- Adaptations of evidence-based interventions will occur in real-world settings.

Despite these areas of agreement, tensions exist between researchers, program developers, community advocates, and other stakeholders because of differing priorities, Murry continued. Community partners are interested in improving services for target populations or solving community problems, in increasing program capacity and staff skill development, in locating more stable funding sources, and in documenting the impact of or need for policy changes so as to secure funding or change views about policies.

Researchers and program developers tend to have a different set of priorities, she said. They are interested in generating publishable research results of interest to academic colleagues, in expanding opportunities for students or project staff to learn and serve, in securing additional grant support, and in raising the visibility of an institution within a community. Achieving these ends leads to professional advancement, Murry observed, even when many of the subjects of a research study or participating in the testing of a program are people living in very stressful situations. These are issues that need to be considered in scaling up programs for uptake in community settings, Murry said.

DISSEMINATING AND ADAPTING INTERVENTIONS

Many researchers believe that by publishing their results in the scholarly literature, they are helping to diffuse innovations that can make a difference in communities. But, as Murry pointed out, “How many people in the community are reading our articles? None. And how many policy makers are reading our articles? Very few. So how do we get the word out?”

Several key factors influence the uptake of evidence-based interventions, she said. A particular intervention may offer an advantage over what is currently available. It may be more compatible with the existing values

and practices of a community. It may be simple and easy to use or provide observable results. It also may allow a user to do a trial run to experiment with an innovation or program.

Organizational change theories point to stages that organizations go through in adopting evidence-based interventions. In general, organizations and communities identify the problem or the need for change, search for solutions, choose a course of action, implement the course of action, and institutionalize the change so that it becomes part of the routine workings of an organization or community. However, various social science theories of change emphasize somewhat different steps by which communities recognize and understand the need for change, take action, and maintain those actions (see Table 2-1). For example, a health belief model may focus on perceptions of risks and benefits; a social cognitive model on expectations, self-efficacy, and reinforcement; and a network model on the structure, beliefs, and behaviors of groups.

Researchers or program developers may believe that an intervention is complete and ready to be implemented when it is delivered to a community. But “it’s a relationship,” Murry reminded the group. To gain acceptance for a particular approach, researchers and program developers need to take the time to build that relationship, she said, noting a potential response: “I’m not going to take something just because you say it’s good. The change is going to be due to the extent to which it’s really meeting the [needs of the] community.”

Researchers and program developers often are reluctant to balance fidelity to a program’s design with adaptations to fit a community’s context. They may believe that the core elements and processes of a program must be maintained for the desired outcomes to emerge, or they may assume that a program’s theory of change is universal. But even if the program’s theory of change is universal, the context differs, Murry explained. “Communities aren’t such that they can do things just the way that the program developer or research scientist does,” she said.

Murry suggested several steps that researchers and program developers can take to prepare for the inevitability of adaptations. They can identify to adopters the core components of a program and provide guidance on how, what, and when to change or adapt a program. They can share available findings of mediational effects and information on all components of the program that may be contributing to change. They can conduct implementation assessments to capture adaptation effects. These steps require that implementation of a program results from a true collaboration in which information flows both ways. Researchers and program developers “could learn a lot from the implementation of our programs in real-world settings by looking at what people do to it once they have it,” said Murry. “If program developers see that the intervention is working well and that

| Stages of Change | Health Belief Model | Social Cognitive Theory | Diffusion of Innovations | Social Networks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precontemplation | Susceptibility | Reciprocal determinism | Relative advantage | Opinion leaders |

| Contemplation | Severity | Behavioral capability | Compatibility | Groups |

| Preparation | Threat | Expectations | Complexity | Adding or removing members |

| Action | Perceived benefits | Self-efficacy | Trialability | Bridging groups |

| Maintenance | Perceived barriers | Observational learning | Observability | Rewiring groups |

| Decision Balance | Cues to action | Reinforcement | Network weaving |

SOURCE: Murry (2016). Available: http://sites.nationalacademies.org/cs/groups/dbassesite/documents/webpage/dbasse_172939.pdf [May 2017].

the program has been adapted to fit the needs of communities, it should be viewed as evidence of balancing fidelity and fit. Both fidelity of implementation and program adaptation are essential elements of scaling up programs,” Murry observed, “and program developers need to be flexible in moving these projects into the field.”

Another aspect of this flexibility is cultural adaptation. Some adaptations may involve minor revisions to the original materials or activities that address superficial aspects of a target population such as language, music, or food, but with the content remaining the same. Alternately, cultural adaptation may involve deeper processes related to the problem of interest, which is more likely to involve the theory-based mediators of the intervention thought to affect change mechanisms or outcomes (Castro et al., 2004). In either circumstance, Murry suggested starting with the community and moving up (Murry and Brody, 2004). A community can be asked how best to infuse and integrate culturally relevant issues in the context of delivering a program, and the community then can help decide what needs to be done, whether superficial or deeper adaptation. An example of the former is translating an intervention into another language, whereas an example of the latter is a change that would affect the values associated with a program in a particular community, particularly as those values might affect customs, religious practices, worldviews, or everyday experiences (Gonzales et al., 2016).

BALANCING FIDELITY AND ADAPTATION

Murry used the Nurse-Family Partnership as an example of a program that balances fidelity and adaptation as it scales up.1 The program partners with communities and provides ongoing support for program implementers. It clearly articulates purposes and is designed to accomplish core objectives. Program implementation is monitored and assessed, and information from implementation is used to improve the program and encourage replications. In this way, the program is implemented with success across diverse populations.

As another example, Murry described Invest in Kids, which is based on a community-researcher broker model.2 The community-researcher broker develops and uses broad-based community support and involvement to identify and pursue the community’s goals. The broker then develops strategies and approaches to improve coordination and thereby promote the sustainability of programs through political support and investment in local

___________________

1 More information about the program is available at http://www.nursefamilypartnership.org [May 2017].

2 More information about the program is available at http://iik.org [May 2017].

leadership. Once programs have been identified for specific communities, Invest in Kids lobbies state legislators and provides data about needs for the program, expected outcomes, costs, and accountability. Invest in Kids then helps to implement programs through agency partnerships and community collaborations while providing ongoing consultation and support for community implementers. In this way, the broker acts as a mediator or conduit to bring all the parties together.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR IMPLEMENTATION

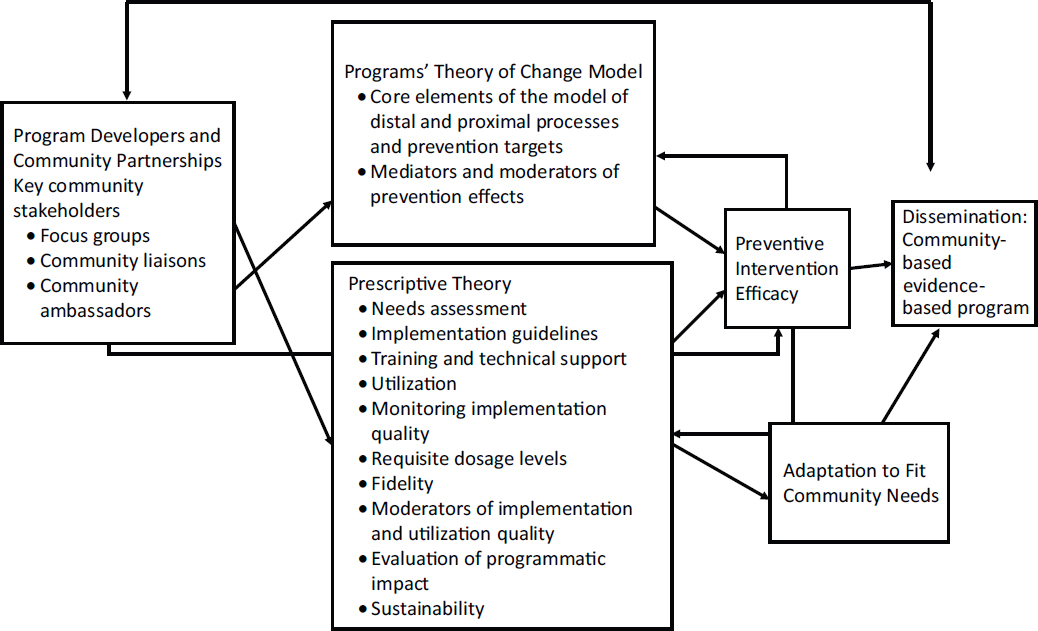

These and other examples have suggested a conceptual model for the development and implementation of family-centered prevention programs in communities, Murry said. In the model (see Figure 2-1), community partners work with researchers and program developers and implementers in developing both a theory of change and prescriptive theories about how a process or program should be implemented in a community. The model links partnerships between program developers and communities to adaptation, fidelity, and dissemination. This understanding informs the intervention, how to adapt the intervention, and how best to disseminate information about that intervention.

In general, reciprocal relationships between researchers and community partners lead to success, Murry concluded. But these relationships require acknowledging that establishing, building, and sustaining collaborative partnerships is a journey that involves researchers, families, and partners within the community.

In that light, she left the workshop participants with several recommendations for the implementation of evidence-based interventions in communities. Partnerships of program developers, researchers, community stakeholders, and others need to observe best practices for scaling up evidence-based interventions, she said. These partners also need to clearly articulate the core components of such interventions and allow for refinement to fit community needs relying on relevant theories, she continued. Establishing criteria and processes can allow communities to ready themselves for scaling up and maintaining evidence-based interventions. And alternative delivery modalities, including those that use 21st-century technologies and media platforms, can help meet the needs of potential program adopters and their targets.

DISCUSSION

A major topic during the discussion period was how programs can be adapted without losing their original intentions and outcomes. As Murry asked, after observing that a program deliverer may not be able to imple-

ment a program as intended: “Do we say to them, ‘I’m taking my program back,’ or do we say, ‘Do it, and let me see what happens as a consequence of what you’ve done?’” The latter approach can lead to new information that can increase a program’s effectiveness not only where a program has been adapted, but also elsewhere. “Then you begin to have an evolving program,” she noted. It may still be necessary to maintain core elements in a wide variety of settings. But flexibility makes a program stronger, and “a strong program should be able to withstand” some degree of change, she said.

David Hawkins, University of Washington, drew a distinction between planned adaptations and situational adaptations. The latter often causes more problems than planned adaptations that are designed into a program, he observed. Before a program is implemented, a community may need to look at a program and ask, “What can we do that works for this community, given our culture, given our heritage, given who we are?” But, he continued, if a community says, for example, that it does not have time for a particular part of a program, core elements may be lost.

Planning for adaptation cannot be done from the top-down, Murry observed. The adaptation actually has to emerge from the partnership with a community, not unilaterally from researchers or program developers.