4

Taking Advantage of Cutting-Edge Methodologies

Community interventions are generally complex and multilevel, and evaluations of such programs often require innovative designs. Such designs might include adaptive and preference-based models, randomized rollout evaluations, and nonrandomized community-based implementation designs. The second panel of the workshop consisted of three presenters who examined several cutting-edge methodologies that can meet the needs of both communities and researchers for information on program implementation and effectiveness.

COMBINING INTERVENTIONS TO ASSESS THE EFFECTS ON OUTCOMES

TimeWise and HealthWise are comprehensive curricula for 8th and 9th graders designed to increase positive leisure time use and experiences, increase self-awareness, increase positive communication with others, establish and maintain healthy relationships, teach skills, and increase knowledge. The goals of the programs are to reduce substance use, risky sexual behavior, and violence while promoting positive youth development.

Both interventions have been studied through efficacy trials, noted Linda Caldwell, distinguished professor of recreation, park, and tourism management and of human development and family studies at Pennsylvania State University. The HealthWise intervention also has been adapted for use in South Africa, where teachers provided feedback in pilot tests and where an efficacy test was conducted in 56 schools. The program has now spread to Zambia “and is ongoing right now, with funding through the University of the Western Cape, not the U.S. government.” Other countries, including Iran, Malaysia, Iceland, China, and Kenya, also have either replicated the program or expressed interest in doing so.

The dissemination of the program has required the program developers to identify universal concepts and needs and distinguish them from local needs, focuses, and processes, said Caldwell. Context can differ greatly from country to country, which can affect how to deliver the content. Pedagogies that may be possible in the United States may not be possible in South Africa in schools with fewer resources. People in different countries may even think of terms like youth in very different ways, Caldwell pointed out.

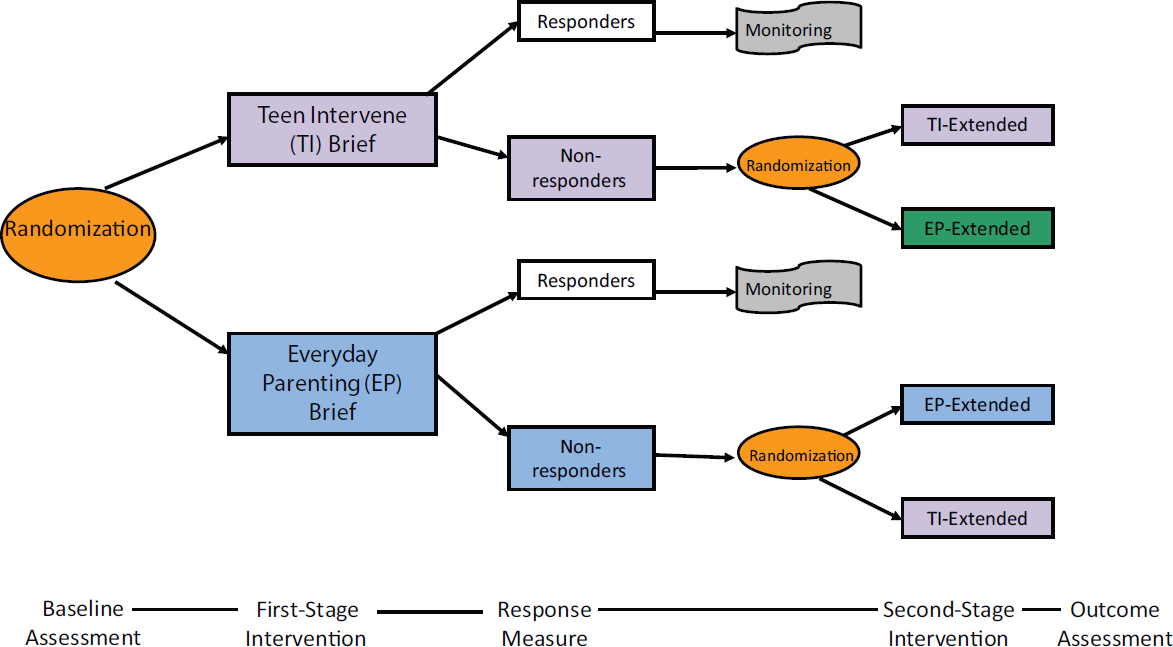

The program developers and evaluators have developed a theory of action that relates independent variables through mediators to proximal and distal student outcomes (see Figure 4-1). They also have developed an experimental design in which groups of seven schools each have different combinations of interventions in the areas of enhanced training, support, and enhanced environments. Classrooms have been videotaped so that these independent variables then can be related through mediators to outcomes.

Research evidence indicates that adolescents who are not intrinsically motivated or who are bored in their leisure time have more developmentally problematic outcomes than other adolescents. But, Caldwell added, the details of how to apply these theories and concepts have generated many questions, which themselves need to be investigated, and include the folowing:

- Can groups work together?

- Who will serve as champion of a program?

- How are the fundamental issues different?

NOTE: Interactions and control variables not shown in the model. Primary outcomes are represented by a solid heavy line, secondary by lighter solid lines. Dashed lines represent relations that will be tested.

SOURCE: Caldwell (2016). Available: http://sites.nationalacademies.org/cs/groups/dbassesite/documents/webpage/dbasse_172957.pdf [May 2017].

- Will the theoretical bases hold?

- What role do language and concepts play?

- For whom and under what conditions is the program effective?

- How best can pilot programs measure processes and content?

- How can sustainability be built into effective programs?

- How can implementation balance fidelity and adaptation?

- How best can adaptation be accomplished?

PRECISION PREVENTIVE INTERVENTIONS FOR YOUTH AT HIGH RISK FOR CONDUCT DISORDER

Evaluative methodologies drawn from other fields have much to offer evaluations of community-based interventions. For example, the National

Institutes of Health has defined Precision Medicine as “an emerging approach for disease prevention, early detection, and treatment that seeks to optimize effectiveness by taking into account individual variability in genes, environment, and lifestyle,”1 and this approach can be taken to optimize behavioral outcomes as well, said Gerald August, professor in the Department of Family Social Science at the University of Minnesota. What has been called precision prevention has generally involved tailoring behavioral interventions to the characteristics of individuals, but it also can involve targeting groups or communities by modifying care delivery systems, optimizing transmission through social networking, or instituting targeted policy or macroenvironmental changes that differ from one community to the next.

The advantage of precision prevention is that it can respond to the wide heterogeneity and variable intervention response that exists among high-risk populations, August observed. It reduces negative effects associated with burden, iatrogenic consequences, and ineffectiveness and can increase adherence with interventions. It also can increase efficiency and effectiveness while reducing costs.

With support from the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the Center for Personalized Prevention Research at the University of Minnesota, which August directs, has been focusing on the prevention of conduct disorder. Five decades of research on ecosystemic, social learning, and social-cognitive interventions have demonstrated that many interventions for conduct disorder work, said August. He continued, “They work modestly. They don’t work for everybody. There are questions about the durability of effects over the long term. They often fail to reach those in most need, the high-risk populations. And even when we get them to the table, participation and completion rates are poor.”

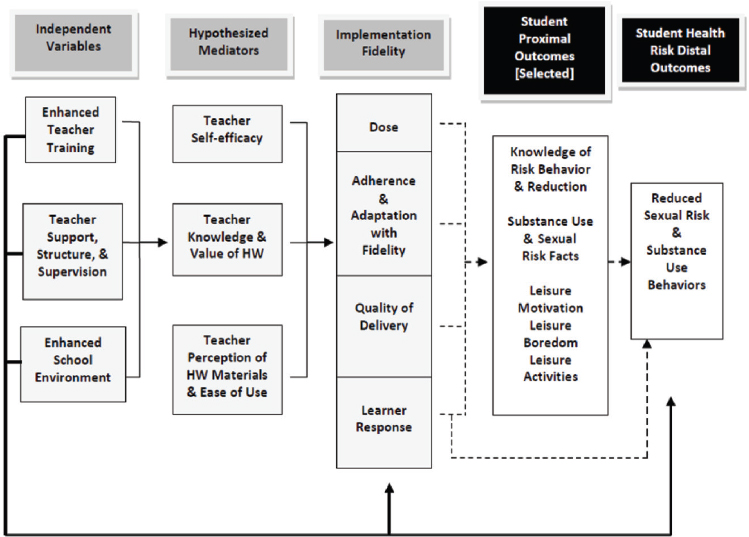

The Center for Personalized Prevention Research has been experimenting with new delivery systems, two of which August described at the workshop. The Sequential, Multiple, Assignment, Randomized Trial (SMART) design uses multiple randomizations to assist in the construction of powerful adaptive treatment strategies. An adaptive intervention tailors interventions over time based on an assessment of ongoing response. In the study, August described, individuals are randomized to two different types of interventions, which allows multiple approaches to be assessed in successive stages of intervention (see Figure 4-2). One is a youth-focused intervention that works on decision making. The other is a parenting-focused intervention that works on communication, supervision, and parental involvement skills. Both are brief, consisting of just two or three sessions. The

___________________

1 For more information about the Precision Medicine Initiative, see https://www.cancer.gov/research/key-initiatives/precision-medicine [May 2017].

idea is that many individuals at low risk will respond favorably and will be stepped down to monitoring over time. However, some individuals will not change their risk trajectory sufficiently. The nonresponders are randomized a second time to either more sessions of the initial intervention or to a different intervention. In this way, four adaptive intervention strategies can be tested over time.

This design makes it possible to see how various adaptive strategies work, August observed. What is the best first-stage intervention for nonresponders? What is the best second-stage intervention? For those who started with either one, did the intervention facilitate downstream effects? Did a youth-focused or a parent-focused strategy serve better in the long run?

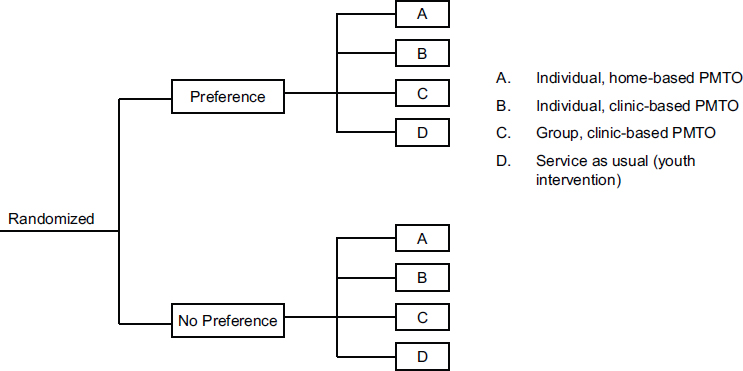

The second model he described is a preference-based intervention. This intervention affords individuals an opportunity to choose their intervention and see whether or not that improves engagement and outcomes. Client participation in health care decision making can improve engagement by providing autonomy, thereby increasing self-efficacy for behavioral change and resulting in enhanced outcomes. The results of understanding why people choose what they choose make it possible to build what are called decision aid interventions, which try to inform them about how to make good decisions.

In one preference design, individuals are randomized either to preference or to no-preference (see Figure 4-3). This design makes it possible to test four different intervention modalities—based on the Parent Management Training-Oregon (PMTO) model to prevent the onset and progression of conduct disorder—in children and families, who can either choose or not choose the treatment they want to receive. Those in the preference group get to choose which intervention they want. Individuals in the no-preference group are randomized a second time. The preference-based model then can be compared with the no-preference-based model in terms of engagement and outcomes. Pre-intervention characteristics also can be examined to look for associations with why a person selected one model over another. What are their expectations about health care? What are their attributions regarding the cause of a behavior? What are their belief systems and cultural traditions? “Those types of variables may be very instructive in helping us understand why people make the choice they choose,” said August. “And if it’s a good choice, how can we build that into decision aids to inform other people?”

The center is also looking at mobile health interventions, just-in-time interventions, interventions that use smart messaging, and health care coaching. “Precision health care, as it has in other areas of medicine, offers very significant progress in the areas of mental health and substance abuse prevention,” August concluded.

NOTE: PMTO, Parent Management Training-Oregon model.

SOURCE: August (2016). Available: http://sites.nationalacademies.org/cs/groups/dbassesite/documents/webpage/dbasse_172950.pdf [May 2017].

RESEARCH DESIGNS THAT REFLECT COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT

Both in implementing and evaluating interventions, researchers need to learn from and be guided by the community, said Hendricks Brown, professor in the Departments of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Preventive Medicine, and Medical Social Sciences in the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. He quoted public health psychiatrist Sheppard Kellam’s first rule of public health: Don’t get kicked out of the community. “It’s funny that we laugh at something like that, [because it] is so fundamental. It is the reason why a lot of people in research think that they can’t work with communities,” Brown said.

Working effectively with communities relies on experience. “You can’t do this by just reading and going to a class,” Brown said. “You have to be fully engaged and have mentors to be able to help and support [you].” Brown also quoted Christopher Harris from the Bright Star Church (see Chapter 3) that people live in communities; they are not there to serve as research guinea pigs. A research agenda might be one part of a community’s agenda, but it is only a part.

Brown also made the point that knowledge and guidance by the community can extend and improve research, not limit it. Researchers never have to give up science when working with a community. But they need to

be more precise even as they remove some of the controls that they might like to impose on a study.

In the Bronzeville community in Chicago, the community and political organization has been outstanding in working with researchers, Brown observed. The community has allowed researchers access to schools and has helped with the completion of student and adult surveys. It has offered feedback on draft surveys to reflect community norms and has otherwise provided opportunities to fill scientific holes. For example, it has advocated the use of treatment as prevention to reduce retaliation, which has become a major strategy in the research going on in the community.

The Communities That Care (CTC) model has been embedded in Bronzeville within a tapestry of existing programs and services. This has made it possible to compare outcomes from the program with current and historical data and to test “one-off” interventions in different contexts. The interventions being studied may include protocol deviations from CTC, which “we know are going to happen,” said Brown. “We want to learn about that.”

As a specific example, Brown mentioned a study of mediational mechanisms. Maps of neighborhood violence, youth exposure to programs, and adult networking and social processes can be compared to examine alternative diffusion mechanisms that indicate how a program is working across a community and among community members.

Brown’s final point involved scientific disparities and scientific equity. Just as health equity can be defined as a fair opportunity for all people to attain their full health potential, scientific equity can be defined as equality and fairness in the amount of scientific knowledge that is produced to understand the potential causes of and solutions to existing health disparities (Brown et al., 2013; Perrino et al., 2015). “We don’t do that in our country,” said Brown. “We have very limited information.” For example, in an examination of 183 preventive trials, only 4 percent were focused on Hispanics and only 9 percent on African Americans, far below their representation in the U.S. population (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2009). Communities do not have enough research findings to do everything they want to do, Brown said, and community research has the opportunity to reduce this disparity.

DISCUSSION

The major topic of discussion during the question-and-answer session was the development of widely shared metrics that can be used in program development, evaluation, and accountability. David Hawkins, University of Washington, observed that many archival data measures are of problem behavior outcomes, even though prevention typically emphasizes strength-

based approaches and protective factors. Risk factors are important, he continued, but determining those factors accurately requires asking young people about both their experiences and the protective factors in their communities. Using those data, communities then can decide what they need to do differently.

As an example of a positive behavior, Caldwell pointed to the work she and her colleagues have done on leisure-based programs, “because kids and teachers really do respond positively.” Their research shows that girls who had higher perceptions of perceived leisure opportunities in their communities had lower rates of substance abuse, which she said was the theory behind the programs.

David Shern, Mental Health America, briefly described work he has been doing with a colleague to develop a set of metrics related to healthy development that can be included in ordinary clinical pediatric encounters. “There’s an opportunity over the next several months to suggest a series of measures that are responsive to the kinds of outcomes we want to achieve in terms of prevention interventions that could be implemented in pediatric practices,” Shern said. He encouraged workshop participants to suggest measures to be included that could contribute to quality improvement and help institutionalize positive measures of development.

Knowing more about both risk and protective factors would advance mediation analysis, observed Patrick Tolan, University of Virginia. While the outcomes of programs are important, understanding how programs work is also important. “How do we start to come to some common understanding of what these programs do and what they don’t do?” he asked. “That’s an area, it seems to me, where there’s been very little good science.”

Risk and protective factors need to be “stitched together” with a wide range of data to understand mechanisms, Brown pointed out, stating, “We need to know how many people come to elementary school, for example, ready to read. That’s a huge factor.” Some existing household surveys provide useful data, but these measures need to be extended, he said. Similarly, August emphasized the need to look at attitudes, values, social competencies, and even neural processes in understanding the mechanisms of change.

Lorece Edwards, Morgan State University, broadened the conversation to the social determinants of health, “which play a key role in risk and protective factors, as well as the determinants of hopelessness, which are a key factor based on culture.” Gender differences also play into outcomes, she observed, as in Caldwell’s observation that the programs she has been studying are more effective with girls than with boys.

Anthony Biglan, Oregon Research Institute, observed that detailed metrics of the health and well-being of children and adolescents could provide opportunities for natural experiments that would enable the selection of better outcomes. “To the extent that we keep our eye on the ultimate

prevalence of problems in the population, and we are carefully measuring that and feeding that back to people and encouraging the kinds of conditions we need to ensure well-being, we will steadily improve,” he said.

The public health community recognizes the need to gather data at the community level, and prominent reports have called for extending this work, said Deborah Klein Walker, Abt Associates. But, she stated, underfunding, discontinuous data, and a lack of political will have resulted in lost opportunities. “You need data at the community level, there’s no question, to do some of the things we’re doing,” she said.