6

How to Sustain Funding

Sustainable funding can ensure both continued implementation of evidence-based programs and continued support for those programs once they are implemented. But what is the relationship between evidence and sustainability? Can the two support each other, allowing communities to continue to receive benefits while additional evidence is generated? Four presenters examined the question of how to sustain funding of evidence-based programs and systems, using both specific examples and broader rationales to support their views.

MAINTAINING A SUCCESSFUL PROGRAM

In the early 2000s, a retired schoolteacher in Tooele City, Utah, named Milo Barry learned about the Communities That Care model and convinced city leaders that the program would address some of the city’s most pressing needs. The result was the successful establishment of several evidence-based courses that were taught in the schools and in the community.

When the initial grant ended, the city faced a choice, said Heidi Peterson, director of the Communities That Care Program for Tooele City, whether to let the program expire or ensure it continued by putting money behind it. Motivated both by the passion the program had inspired and by the solid evidence base it had generated, the city made Communities That Care a line item in the annual city budget. The mayor asked for $160,000, which is “enough to pay for a lot of other city services,” Peterson noted, but the mayor “was able to sell that because we had an evidence-based system in place and there were data showing that it would do what it said it would do.”

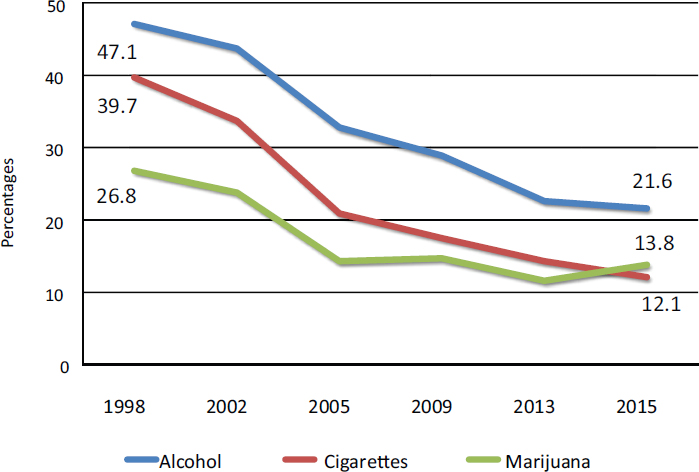

Since 1998, the percentage of lifetime use of alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana by Tooele City schoolchildren has dropped substantially since the Communities That Care Program was implemented, demonstrating the effectiveness of the program and contributing to its continuance (see Figure 6-1). The presence of the program also made it possible to bring in other evidence-based programs when needs arose. The Second Step Program addressed low commitment to school; the Q.P.R. Suicide Prevention Program addressed depressive factors and suicidality when a wave of suicides occurred in the community; and the Guiding Good Choices Program addressed family conflict. In addition, the Mayor’s Recognition Award Program singles out up to eight city youths at every city council meeting for their prosocial achievements. “Over 10 years, that’s over 1,600 kids who have been recognized,” said Peterson.

TAKING ADVANTAGE OF SOCIAL NETWORKS

As demonstrated by the experience in Tooele City, programs that produce positive outcomes after implementation are more likely to be sustained. Replicating such successes requires the diffusion of innovation, observed Marc Atkins, professor of psychiatry and psychology at the University of Illinois at Chicago, who works with colleagues to redesign community mental health services for urban children in poverty. But people take up new ideas at very different rates, he noted. For example, when Atkins and his colleagues go into urban schools, many teachers are not initially interested in working with them. “There’s a lot of wisdom involved in that,” he observed. “Early adopters may pick things up quickly, and that may give us a sense that everything’s catching on, but it’s not until later

NOTE: Data from Tooele City School District, grades 6-12.

SOURCE: Peterson (2016). Available: http://sites.nationalacademies.org/cs/groups/dbassesite/documents/webpage/dbasse_172963.pdf [May 2017].

that we find out whether or not it’s catching on with others, whether we’ve hit a tipping point.” For that reason, a lack of sustainability for a program may reflect program developers not waiting long enough for social networks to embrace a program.

People are influenced by others in their social networks. In particular, network analysis has pointed to the importance of key informants as a source of information and advice. Key informants “get new information into a setting,” said Atkins. “They actually don’t have a major influence on picking up the intervention.” Rather, they encourage other people to adopt and use an intervention.

The lesson to be learned, Atkins said, is to “pay attention to the social networks within these settings.” For example, Atkins and his colleagues have been identifying teachers who are influential with other teachers and asking them what parts of programs are interesting and important. These influential teachers are then in a position to share that information, but, he noted, “this is going to take time, because people have to see other people in the social setting who are in a similar situation.”

Drawing on these ideas, he and his colleagues have been taking a public health approach to mental health. They look at the settings that are most influential in children’s development and think about how those settings can be modified to produce positive outcomes. This work is not necessarily in the province of mental health providers, Atkins observed. Rather, he said, parents, teachers, school program staff, and mentors “are the real mental health providers, if you will. Not that we want them to do therapy, but they have the major influence, and our work is in support of them.”

Achieving this goal requires realigning mental health resources in urban communities, Atkins explained. In Chicago Public Schools, the Chicago Park District, and elsewhere, staff who in the past waited in clinics for families who often did not show up have been reallocated to the settings that are most important for children. “We prioritize settings over programs,” Atkins said. In some cases, this requires that programs adapt to their settings, but “we can learn from adaptations by thinking of them as indicating the priorities or the tendencies of people in that setting, as opposed to deviations from fidelity.” Thinking of programs in this way promotes a natural extension from prevention to intervention to positive adaptation.

COMMUNITY BENEFIT: A POTENTIAL SUSTAINABILITY MECHANISM

One great advantage of evidence-based programs is that they have the data needed to justify their continuation, observed Sue Thau, a policy consultant for Community Anti-Drug Coalitions of America. For example, the Drug Free Communities Support Program has required that each grantee provide baseline data and collect data over time to prove the program works. According to a national evaluation of the program, grantees have been able to produce substantial declines in alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, and prescription drug use. “This is the basis of sustainability, having something that you can show from a baseline has made a gigantic impact,” she said. But national evaluations by themselves are not enough, Thau continued, pointing out that “you need to prove that it works in your community, and that it’s worth being funded in your community.” In the Franklin County and North Quabbin area in Massachusetts, Drug Free Communities funding through the Communities That Care prevention system resulted in major reductions in alcohol binge drinking, marijuana use, and cigarette use from 2003 to 2012, according to teen health surveys conducted over that period, along with major increases in high school graduation rates and bonding to school.

Many communities now have an opportunity to replicate such successes through the Community Benefit Program, Thau observed. Overseen by the Internal Revenue Service, the program requires nonprofit hospitals

to invest in the health and health care of their communities in exchange for their tax-exempt status. Before the Affordable Care Act, nonprofit hospitals invested much of their Community Benefit funds in charity care or uncompensated care. Now that the number of uninsured people has fallen, nonprofit hospitals are required to do a Community Health Needs Assessment every 3 years, including a prioritized description of community health needs and a process for prioritizing such needs. Hospitals then must develop an implementation strategy that describes how the needs identified in the assessment will be met and why some needs may not be addressed.

In this way, Community Benefit funding can meet an “amazing” variety of needs, noted Thau, including physical improvements and housing, economic development, community support, leadership development and training for community members, coalition building, community health improvement advocacy, and workforce development. In Franklin County, for example, the community coalition introduced the data generated from the funding under Communities That Care into the Community Health Needs Assessment. Community Benefit ended up funding the coalition building, continued collection of data, and backbone support for the coalition. “We have a lot of examples of coalitions that are getting their data into these Community Health Needs Assessments, and are partnering with nonprofit hospitals, to be able to get funding,” she said.

Thau concluded with several lessons learned. She urged using community coalitions’ health sector contacts to get data from the coalitions into Community Health Needs Assessments. Community leaders also can use hospital contacts to share the value of multisector, data-driven strategies and demonstrate population-level outcomes due to the implementation of coalition strategies. Finally, she urged community leaders to package the entire process into a turnkey approach to solve problems for both hospitals and communities. “Hospitals don’t want to start developing programs or picking a program off a list. They want someone to come in and say, ‘Here’s the problem, I know how to solve it, and I can prove that I can solve it, because I have the data to show you that, over time, I’ve already done an amazing job solving this problem.’”

USING THE FLEXIBILITY OFFERED BY MEDICAID

Given the prominence of health care institutions in communities, Medicare and Medicaid will continue to be major funders of the services that communities need, observed Ellen-Marie Whelan, chief population health officer for the Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), which means building on the payment system that currently exists. “As much as we would all love to perhaps blow the whole system apart and start anew and be able to fund some of

these really creative models that we have going forward, the truth of the matter is we have what we have now in terms of payment,” she said.

Government is trying to move away from fee-for-service payments toward population-based payments. This should free up programs that were hampered by a fee-for-service approach, Whelan said. For example, “you can better use the entire workforce, whether it’s the traditional clinical workforce or more of the community health workforce, as long as you’re moving toward goals.”

The question is how to help people and systems make the transition, she said. One answer is by taking advantage of the flexibility that states have in implementing and funding innovative programs. The federal government makes this flexibility available to states, both through authorities under the law and through waivers if necessary. Also, a lot is going on behind the scenes, Whelan said, as the federal government tries to help states do a better job.

Social service providers sometimes express the opinion that they do not want health care to become involved in their activities because they fear onerous regulations and other restrictions. But the health care delivery system has a lot of money, Whelan pointed out, and the funding is relatively dependable.

As an example, Whelan cited an information bulletin written with the Health Resources and Services Administration on how states can use federal funding in part to support maternal and infant home-visiting programs, which have more than 30 years of evidence showing prolonged benefits for children. CMS also has worked with the Department of Education to clarify how providers could be paid for services delivered in schools. It worked closely with the Department of Housing and Urban Development on Medicaid’s funding for supportive housing services to help move from institutional care to home- and community-based services. CMS has put out guidance on how states can make sure that they are reimbursing pediatricians for doing maternal depression screenings. It has worked with the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration on the development of certified behavioral health centers that merge community behavioral health and physical health. It has issued information bulletins on foster care; the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment program; state mental health programs; and other topics.

Whelan invited the workshop participants to encourage their states to work with CMS on flexible funding mechanisms. She also asked for their help on learning how best to scale and disseminate programs. “What are some of the elements that we could be pulling together to look at the scale and spread of some of these models?” she said. “How we did it with the Nurse-Family Partnership is an interesting example. [CMS] looked across states to see what kinds of funding they were doing, and we’ve pulled

together a model that, if you wanted to do a model like the Nurse-Family Partnership, here’s ways you can move forward.”

Working with CMS can be a major investment for states, since they need to provide some of the funding themselves. But “it’s worth the investment,” she said. “These things that we’re piecing together now . . . will lay some groundwork for how we’re going to move forward.”

DISCUSSION

From Sustainability to the Social Determinants of Health

Following up on Whelan’s presentation, several workshop participants observed during the discussion session that payment systems can be a powerful influence on the sustainability of funding. For example, David Hawkins, University of Washington, made this point in the context of emphasizing healthy parenting in primary care, and particularly in pediatric practices. He described a possible scenario: “Your pediatrician or your family practice doctor says, ‘You’re having behavioral management problems with your 2- or 3-year-old. We’re doing a program called Incredible Years here at the clinic, and we’d like to recommend that you do this.’” Programs that have taken this approach have had strong responses from parents, he pointed out. However, with a fee-for-service payment system, it can be difficult for physicians to be reimbursed for this work.

Whelan said that CMS has been supporting work of this type, such as centering programs that provide care for pregnant women and for parents in small group settings. In those cases, the providers have been receiving an extra care management fee, and states can look to such programs as precedents. They also have other options, such as targeted case management under Medicaid, which can provide extra care coordination and services. “The best thing is to capture where it’s happening in some states, pull back together, and then we can see what the next step would be,” she suggested.

Kelly Kelleher, National Children’s Hospital and panel moderator, also pointed to the possibility of using savings generated by accountable care organizations to invest in preventive services. “There are ways to do that . . . if we can make a good return-on-investment argument, a utilization argument, and an outcomes argument,” he said. He added, however, that spending such savings on things like housing, transportation, and other services can “raise eyebrows.” Medicaid and state officials do not necessarily react positively to investing in community crime control, even when that is exactly what is needed, he commented.

Atkins observed that much of his school-based work has been funded through Medicaid. “We just make sure that everything that the mental health providers are doing is billable, which involves writing treatment

plans and so on,” he said. “We have found that much of what we would consider good practice, including the Good Behavior Game, is billable.”

Atkins also called attention to federally qualified health centers, which were emphasized in the Affordable Care Act. One problem with the centers is that they do not have benchmarks that relate to children’s behavioral health, he said, which makes it hard for them to address that issue to the extent that it needs to be addressed. He said a second problem is that community members working on prevention programs cannot bill through the federally qualified health centers, though he and his colleagues have started establishing collaborations between the community mental health staff and federally qualified health centers to affect both health and mental health in a synergistic way.

Whelan cited the difficulty of doing research on children covered by Medicaid, as it is very difficult to get datasets associated with their health and well-being. If those data could become available to researchers, Whelan suggested, they could do a better job of evaluating programs and comparing programs and state efforts.

Thau noted, as a former budget examiner with the Office of Management and Budget, the difficulties associated with integrating all services into the health care system. “We have to fight to keep [and] get more differentiated funding for things like the social determinants of health, and for public health, and for things that don’t necessarily belong in the health care system,” she stated. Preventive programs are massively underfunded and have been losing funding in recent years, she said, and they need to be defended.

Devoting Attention to the Social Determinants of Health

How to sustain prevention programs is closely related to the much broader program of bringing societal attention to bear on the societal factors that affect health. Atkins pointed to the problems, given the way children live and the issues they face, caused by preventive efforts that remain within their own silos. In his work in Chicago Public Schools, he and his colleagues have become integrated with mental health providers and with community members. “It’s very hard for me to stay in my silo anymore,” he said. “It’s very hard for me to say, ‘Sorry, I just do mental health. I don’t do education. I don’t do substance abuse.’” Peterson noted that the same thing has happened in Tooele City, where collaborations involve “everyone from housing to medicine to the schools. . . . If we’re contacted about something, we may not be able to offer that program or service, but we know who does.” Such collaborations can be fostered, Whelan added, through metrics that require sectors to work together to achieve success.

Anthony Biglan, Oregon Research Institute, pointed to the broader

potential of metrics and data. The types of programs and the details of their implementation differ throughout the country. By measuring these differences and comparing them with health and well-being outcomes for young people, the efficacy of what is being done can be determined. “We are the people who will change society, not the politicians, and we’re doing it on the basis of data,” Biglan said. Furthermore, added Whelan, data are available from adult health care, public health, and social services that could provide valuable information for programs directed at youth.

Kelleher wondered if the idea of reciprocity might be better than that of sustainability, emphasizing engagement between communities and programs rather than a one-way flow of support from communities to programs. Such an approach also might tie in better with ways of addressing the social determinants of health, such as housing vouchers, poverty relief programs, and other social services, he said.

This page intentionally left blank.