7

Being Responsive to Communities

Communities have both needs and wants in considering the implementation of evidence-based interventions. Distinguishing the two and addressing them appropriately requires researchers and program developers and implementers to be responsive to communities. Is an evidence-based intervention efficacious for a particular population? When should a program be adapted to meet a need that a community identifies as a high priority? The

final panel of the workshop considered these and other questions in the context of the challenges and opportunities particular communities face. In the process, they revisited many of the themes that emerged during the workshop, such as the inevitability of program adaptations, the advantages of integrated care, and the need for reciprocal relationships among stakeholders.

IDENTIFYING PRODUCTIVE ADAPTATIONS

Responsiveness to the needs of a community can involve showing communities the best way to adapt a program rather than assuming that a program will be implemented and conducted with high fidelity, explained William Hansen, who was president of Tanglewood Research from 1993 to 2016. For example, All Stars is a commercially available drug abuse prevention tool designed for use in schools. In a study in Chicago involving 43 teachers, researchers selected 3 excellent teachers, 3 middle-of-the-road teachers, and 3 teachers who had challenges delivering the program. Every session taught by all 9 teachers was videotaped, resulting in about 27 class sessions for each teacher. The adaptations they made in the program were coded and sorted into adaptations that fit or did not fit with the program model.

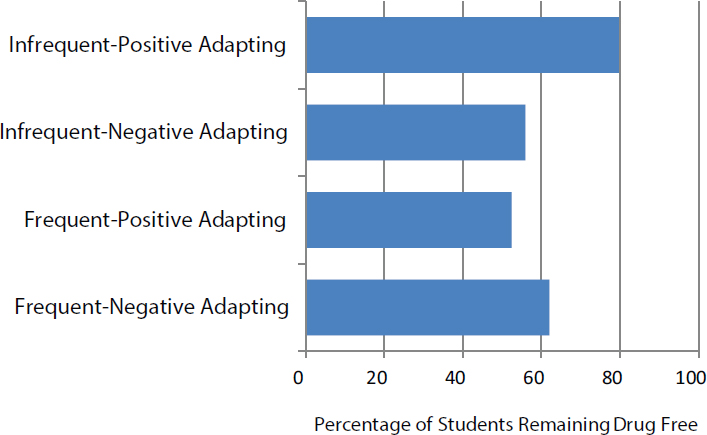

Every teacher, in every session, made some sort of an adaptation to the program, Hansen observed. “If there’s this idea in somebody’s mind that you’re going to create an evidence-based program, and you’re going to give it out there, and people are going to do it exactly the way you say it should be done, that does not exist,” he said. However, some types of adaptations produced better outcomes than others. In particular, infrequent adaptations that had a positive fit with the program produced better outcomes in terms of students remaining drug free, than did frequent adaptations that either had a positive or negative fit (see Figure 7-1). “Those teachers who stuck with the program . . . made adaptations that fit with the model,” Hansen said. In turn, the program has taken some of the positive adaptations and incorporated them into revised versions of the curriculum.

Another study of the program looked at teacher effectiveness in Belfast, Northern Ireland. The more engaged students were with the program, the more likely they were to show a beneficial change in such mediation influences as making a voluntary personal commitment to avoid alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs; perceiving that drug use did not fit with their lifestyle; understanding that drug use is not as common as some people might think; having a positive relationship with their parent develop over the issue; and bonding to their schools. “You have to deliver [a program] well and deliver it in a way that’s engaging, and that doesn’t always happen,” Hansen concluded.

SOURCE: Hansen (2016). Available: http://sites.nationalacademies.org/cs/groups/dbassesite/documents/webpage/dbasse_172967.pdf [May 2017].

THE ADVANTAGES OF INTEGRATED CARE

Another way to meet the needs of communities is through the integration of behavioral health services, said David Kolko, professor of psychiatry, psychology, pediatrics, and clinical and translational science at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. Integration can engage families, provide holistic care, improve the quality of care, and reduce costs, and research bears out these observations, he noted. Asarnow et al. (2015), in a meta-analysis of 31 randomized controlled trials, found that various levels of integration all led to better outcomes, though most of these studies focused on externalizing rather than internalizing problems. The overall effect size was about 0.42, which is modest in overall magnitude but significant, Kolko noted.

Programs were more effective in improving mental health care when they were treatment rather than prevention programs. Also, more collaborative care had a larger effect size than alternative care delivery models, though this difference was not significant. But the evidence suggests that integrated care clearly has an advantage over specialty health care, said Kolko, paralleling what has been found for three decades in adult literature. “Still, there isn’t a lot of direction from the research on how to do it, and how to do it well,” he observed.

Integrated care involving partnerships among primary care and behavioral health providers has three basic levels in communities, noted Kolko. The first is coordinated care, which involves either minimal collaboration or basic collaboration at a distance. The key element in this kind of care is communication.

The second is co-located care, involving either basic collaboration onsite or close collaboration onsite with some system integration. The key element in this kind of care is physical proximity.

The third is integrated care, involving either close collaboration, approaching an integrated practice, or full collaboration in a transformed or merged practice setting. The key element in this kind of care is practice change. Though desired, developing this level of care requires attention to several resource needs and challenges.

Kolko observed that people do not ask for programs or practices; they ask for help with a problem. That is both a challenge and a blessing, because it implies that communities do not necessarily want what programs do well, but they want to deal with a problem where they are not doing well, “and that’s the first step in a collaboration.” Also, communities want to gather data first and be provided with evidence second, Kolko said.

Kolko noted that patients are more likely to attend care sessions if they are getting behavioral health care in a primary care setting than if they go to specialty care. “We found that if you build it, they will come,” he said. Patients and their families far prefer to get behavioral health care in the primary care setting than in their home or a mental health clinic. Besides improved child behavior, caregivers report less distress and burden on children when behavioral health care is delivered in pediatric settings. Some evidence suggests long-term clinical benefits, and positive benefit-cost ratios are starting to appear. It is harder to make prevention meaningful and marketable without referring to the data or to the particular types of adverse outcomes that it can prevent, Kolko observed, adding, “Then it’s an easier conversation.”

Kolko also outlined some of the challenges facing greater collaboration. Medicine and behavioral health have been difficult to integrate due to different service delivery systems, regulations, resources, and funding sources. They can have a hard time working together when the roles for care integration are uncertain or unclear. Costs and reimbursement remain problems, he said, and not everyone is a good fit for collaboration.

UNITING BEHIND PREVENTION

Integration is a hallmark of the Kaiser Permanente Northern California health care system, which has 4 million members in and around the San Francisco Bay area and accounts for 46 percent of the commercial market

share in the region. More than 500,000 members are adolescents, with a great deal of ethnic, cultural, and socioeconomic diversity. The system has a fully integrated electronic health record (EHR) system, carved-in mental health and chemical dependency treatment services, and a capitated payment model, which makes it “a really interesting place to study implementation,” said Stacy Sterling, a scientist with the Drug and Alcohol Research Team at the Kaiser Permanente Northern California Division of Research.

The Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) Program is an intervention for adolescents and adults who are at risk for substance abuse problems and other behavioral health problems. In a study of the adolescent program in pediatric primary care, one group of pediatricians was trained to deliver all aspects of SBIRT, another had embedded clinicians in pediatric practices, and a third delivered usual care. Initial results have looked at rates of screening, referral to treatment, treatment initiation, and engagement rates (Sterling et al., 2015). But what Sterling emphasized at the workshop was the finding from the study that families, teens, and providers all wanted expanded brief intervention services in pediatric primary care and more parent and family engagement in these programs, pointing to the value of integration.

Sterling also described a study of the adult SBIRT program, which she described as “a blueprint for our rollout of adolescent SBIRT across the region.” The program has very aggressive targets: 90 percent for screening, and 80 percent for brief intervention. That study has led the system to adopt the program across the entire region.

Sterling listed several key factors in implementing a comprehensive and large-scale program like SBIRT. Leadership support is critical, she said: “Even if it doesn’t mean providing resources, just showing the organizational will and saying that we are interested in doing this, and this is something that we should be doing, has been critical.” The intervention team is multidisciplinary, including researchers, primary care providers, substance abuse counselors, and mental health clinicians. An implementation facilitator provides coaching, and technical support is provided in person and by phone and e-mail. Having a robust EHR system has been important, and access to data is essential, she said. Monthly performance reports compare regions, facilities, and providers. Abundant information is available to providers and to patients in different languages.

Sterling pointed out that Kaiser Permanente’s community is not only families and youth, but also pediatricians and other providers. They have competing priorities, which is why Kaiser is trying to increase capacity so services can be available, perhaps by relying on providers other than pediatricians or moving services into pediatric primary care, which she termed a nonstigmatized place compared with specialty treatment clinics.

Sterling also pointed out that Kaiser Permanente is dedicated to pre-

vention. It has population health management programs in hypertension, diabetes, weight, and exercise. It is doing innovative work in addressing the social determinants of health, such as challenges with transportation, food, or utility bills. It is beginning to do work on adverse childhood experiences. “These are all tied together, and, of course, they are tied to the bottom line, which leadership is certainly aware of,” she said.

LISTENING TO COMMUNITIES

To implement evidence-based programs in communities successfully, “you have to look at what the makeup of a community is,” said Albert Terrillion, deputy director for evaluation and research for the National Coalition Institute of the Community Anti-Drug Coalitions of America (CADCA). “You have to look at who’s there, have conversations, and really pay attention to what they’re saying.”

Founded in 1992 on a recommendation from the President’s Drug Advisory Council, CADCA supports a comprehensive data-driven approach to prevent the use of illicit drugs, underage drinking, youth smoking, and the abuse of medicines. It represents more than 5,000 community coalitions and has the mission of strengthening the capacity of community coalitions to create and maintain safe, healthy, and drug-free communities globally.

“The work starts from partnerships and relationships,” said Terrillion. Coalitions receive three periods of training during their first year, with continued technical assistance, training, and support throughout and after that first year. Relationships start from the ground up, he said. With training and technical assistance, coalitions have the capacity to implement essential processes. They can pursue comprehensive strategies to change communities and improve population-level outcomes.

Terrillion distinguished between what he called a “low-agency” and “high-agency” evidence base. High agency refers to a relationship with a lot of contact and back and forth with community members. Low agency refers more to the political context as a way to create community change. For example, many of the interventions promoted by CADCA are low-agency approaches that affect policy in such areas as limited hours for the sale of alcohol, taxes, and other evidence-based practices.

High-agency relationships can be more complicated, Terrillion observed, in part because communities are diverse and always changing. “We have to be very careful about what we drop into these communities that doesn’t come from within those communities,” he said. Also, many communities do not have abundant resources, so it may be necessary to find outside sources of support. Finally, researchers cannot just drop into communities and deliver knowledge, he said. They need to bring people

back to their offices and make them a part of the decision-making process. “By listening to the people who are living there, we can pay attention to the social determinants [of health] and be mindful of the needs that are there,” he stated.

He also observed that prevention saves money in the long term, though more needs to be learned about this issue. He noted, “If we’re going to ask CMS to pay for this, and if we’re going to ask for insurance to pay for this, we’re going to have to determine what those numbers are.”

GIVING COMMUNITIES A VOICE

Familias en Acción, which is a community-academic research partnership to develop, implement, and evaluate youth violence prevention programs in an urban Latino community, has gone through four different projects to date, said Manuel Ángel Oscós-Sánchez, professor of medicine in the Department of Family and Community Medicine at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, and that experience has taught him what communities want: “They want to have a voice. But that’s not enough. They want to be heard.” Too many times, said Oscós-Sánchez, he has seen programs that did not have this community input. According to him, “That won’t work very long.”

Researchers are encouraged to have cultural competence to work in communities. But the people who really have cultural competence, said Oscós-Sánchez, are the community members who are able to work with researchers. “We were lucky, in our community, that we had some bold community members who stood up and said, ‘No, that’s not going to work, it has to be this way,’ and we listened to them. Power goes in multiple directions,” Oscós-Sánchez stated.

Communities do not need someone from the outside to tell them what is wrong with them and how to fix it. Rather, they need someone who can do what Oscós-Sánchez called genuine listening. He was involved previously in the Communities That Care system, which begins by asking communities about the issues that they view as critical. “Going through that process was very fruitful in letting the community tell us what it was that they needed,” he said. “We built on that, in terms of developing programs based on what the community said that they needed.”

One form of expertise that communities do need is in developing community meetings, Oscós-Sánchez noted. The person who is most reluctant to talk at a meeting may be the person who has a key idea. Researchers need to provide their expertise “in developing those processes and running the meeting so that those ideas actually have a chance to come out,” he said.

Researchers also have expertise in evaluation, and communities generally are willing to engage in that process. An evaluation with which Oscós-

Sánchez was involved found that a particular program was not working in the community, “and they were willing to accept that and to move on to other strategies.”

Finally, communities want to be acknowledged for all the work they do in designing, implementing, and evaluating programs, Oscós-Sánchez said.

DISCUSSION

Policies and Programs

Much of the discussion following the presentations focused on the distinction made by Terrillion between low-agency and high-agency programs. Sue Thau, CADCA, for example, pointed to the power of environmental policy strategies. Bans on smoking indoors, restrictions on sales to youth, and changing social norms all had dramatic effects on smoking trends. “We can’t miss the public health aspect of this and the types of strategies that get us population-level outcomes. . . . If you go from programs to social determinants of health, you’re missing the whole public health part of this that is population based,” she said.

Terrillion agreed, observing that “culture eats strategy for breakfast.” Hospitals are spending hundreds of millions of dollars through Community Benefit programs, and a lot of that is going for public health. “There’s promise there, but we’re scratching the surface when it comes to those kinds of things,” he stated, referring to environmental strategies suited to deal with issues like the opioid epidemic as an example.

Hansen pointed out that “part of what helped tobacco control and drinking were data that showed that these broad social policies had an effect. If there hadn’t been the data, . . . it wouldn’t have had the support.” As Sterling pointed out, evidence on costs and benefits does exist, but there is a disconnect between that evidence and the people who are making decisions in communities. The information needs to be packaged in ways that policy makers and community members can understand and embrace, she said.

Prevention and the Social Determinants of Health

Workshop participants also discussed the relative merits of preventive programs and their relationships to the social determinants of health. For example, Kelly Kelleher pointed out that prevention in an adult population can have relatively short-term payoffs. “If you try to prevent diabetes in an adult population, or heart disease recurrence, or anything like that, you can see a benefit within a year,” he said. Prevention in children has a much longer time frame, he added, noting, “Pediatric care is a long-term

process. Community development is a long-term process. Family engagement is a long-term process. These are results that have 5-, 10-, and 15-year outcomes.”

Sterling pointed out that the Affordable Care Act, by requiring that children can stay on their parents’ health insurance policies through age 26, implicitly makes this point. She also observed that growing information about comorbidities, where behavioral health problems cause physical health problems that translate into costs, can help show how preventing behavioral health problems can lessen physical problems.

Hansen pointed to the work that Kaiser Permanente is doing with systems in the community, such as school-based health centers and federally qualified health centers. People come and go as Kaiser members, so the system has a stake in keeping everyone in the community healthy regardless of insurance coverage at the moment. If all systems have an emphasis on prevention, all of them will benefit over time.

However, in response to a question about how best to change the systems woven into the lives of children and adolescents, such as the public education, health care, and social service systems, to serve communities, Hansen pointed to how much has changed in the past 40 years, and the pace of change is even greater today. “I’m having a very difficult time figuring out what 10 years from now these systems are going to look like,” he commented.

As Joyce Sebain, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, pointed out, a public health approach encompasses the social determinants of health because it includes all of the sectors—including housing, labor, employment, and business—that need to be at the table. She also pointed out that when people talk about health, they still do not necessarily think about behavioral health.

Patrick Tolan, University of Virginia, emphasized the concept of positive youth development. Education is part of how society produces healthy people. But education includes things like self-control, emotional literacy, and managing one’s body. Policy makers and grant makers are starting to realize that education and health are not two sectors; rather, they are intimately tied, he said, noting, “How we educate kids, and opportunities to educate kids, have big effects on what our health care costs and the health of the nation are.” Oscós-Sánchez agreed but argued against broadening the missions of schools too greatly. “They need equality in education so that they can then become competitive in our world. . . . That’s why I’m always resistant to doing things during school time, because I want my kids to learn how to do math and science and read and learn the fine arts. . . . We can’t forget the inequalities in our educational system that then have long-term effects,” he asserted.

Anthony Biglan pointed out that the scientific knowledge already exists

to ensure that virtually every young person arrives at adulthood with the skills, interests, values, and health habits they need to lead a productive life and have caring relationships with other people (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2009). “That’s a vision that we need,” he said. And as Atkins concluded, “What is the new paradigm? How do we do this? It’s not enough to say social determinants are important. That’s not going to get us anywhere. What’s going to get us somewhere is to say, How can we contribute to this? What is it that we can do differently?”