5

Second Research Session: Social Interaction

The second research panel was moderated by Thomas Fingar (Stanford University) and showcased cutting-edge work in the area of social interaction. Panelists included Joshua Epstein, professor of emergency medicine at Johns Hopkins University; Susan Fiske, professor of psychology and public affairs at Princeton University; and Mathew Burrows, director of the Atlantic Council’s Strategic Foresight Initiative. Panelists presented overviews of their research programs and highlighted key findings, methodologies, data considerations, and relevance to the work of analysts in the intelligence community (IC).

AGENT_ZERO AND GENERATIVE SOCIAL SCIENCE

Joshua M. Epstein discussed agent-based computational modeling in the social and behavioral sciences (SBS) and, in particular, the use of artificial societies composed of interacting software individuals. He based his address on his most recent book, Agent_Zero: Toward Neurocognitive Foundations for Generative Social Science.1 According to Epstein, “Agent_Zero is meant to be a neurocognitively grounded agent, capable of generating a wide range of important phenomena, including collective violence, financial panic, endogenous networks, [and other] collective be-

___________________

1 Epstein, J.M. (2013). Agent_Zero: Toward Neurocognitive Foundations for Generative Social Science. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. This volume is the third in a trilogy of books on agent-based computational modeling, all of which have advanced the generative explanation of macroscopic social regularities.

havior.” He noted that Agent_Zero is designed to be a mathematical and computational alternative to the “rational actor.”2

With generative modeling, according to Epstein, the idea is to explain social regularities, such as wealth distribution, disease dynamics, settlement patterns, or segregation, by “growing them” in artificial societies on timescales of interest to humans. In other words, the macroscopic patterns emerge from agent interactions at the micro level. Epstein reported that Agent_Zero is different from other mathematical modeling because it tries to encompass emotional dynamics and cognitive plausibility. Specifically, agents in the model are endowed with distinct affective, deliberative, and social modules grounded in neuroscience. These internal modules interact to produce individual behavior that may be far from rational. The interactions of multiple agents of this new type generate a wide variety of collective dynamics, such as violent mass behaviors. In this model, Epstein noted that the minimum characterization for cognitive plausibility includes emotions, bounded deliberation, and (endogenous) social connection.3

Epstein pointed out that the idea of the book was to start a synthesis; the components in the model are all provisional and can be improved and extended.

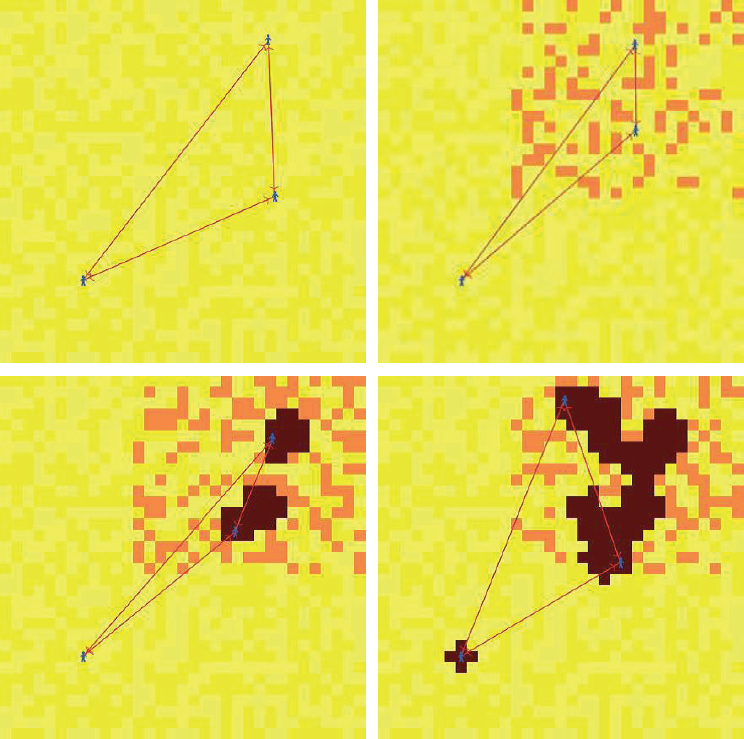

Epstein provided an example of how the model might be used as a conflict interpretation. Figure 5-1 depicts three Agent_Zero–type individuals (in blue). He said they could be considered mobile soldiers occupying a landscape of indigenous sites (yellow). The latter are not of the Agent_Zero type but are simply passive (stay yellow) or actively aggressive (turning orange at some stochastic rate). In response to the indigenous sites, there is a binary retaliatory action that occupying agents can take: destroy all indigenous sites (indiscriminately) within some radius (destroyed sites become dark red). Taking or not taking the retaliatory action depends on the affective, deliberative, and social forces operating inside the occupying (Agent_Zero) agents.

___________________

2 The so-called rational actor model has dominated mathematical social science since the work of John Nash: Nash, J. (1951). Non-cooperative games. Annals of Mathematics, 54(2):286-295.

3 The model follows explicit mathematical equations. The affective module is a generalization of the classical Rescorla-Wagner (1972) learning algorithm [Rescorla, R.A., and Wagner, A.R. (1972). A theory of Pavlovian conditioning: Variations in the effectiveness of reinforcement and nonreinforcement. In A.H. Black and W.F. Prokasy (Eds.), Classical Conditioning II: Current Research and Theory (pp. 64-99). New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.] The deliberative module computes a moving average of local relative frequencies over a memory window. The social component—the inter-agent weights—are based on a strength-scaled affective homophily. Epstein has developed both differential equation and agent-based computational versions of Agent_Zero. To ensure complete replicability, all code and all assumptions for all runs are explicitly provided in the book or on its Princeton University Press website.

NOTE: Agent_Zero fixed in southwest with zero direct stimuli. Others in northeast experience violent action stimulus. By dispositional contagion, Agent_Zero acts.

SOURCE: Epstein, J.M. (2013). Agent_Zero: Toward Neurocognitive Foundations for Generative Social Science. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Reprinted with permission.

According to Epstein, their “affect is constructed in this model by having agents fear condition [modeled classically] on local aversive stimuli. The bounded rationality [i.e., deliberative] component is [represented by having them] take the local relative frequency of ‘bad’ actors over total actors within their sensory radius, or ‘vision.’ The sum of those is called the [agent’s] solo disposition.” But, Epstein continued, the other occupiers also have solo dispositions that weigh on the agent. This weighted (social) sum is

the agent’s total disposition to retaliate. He explained that if and when the total disposition exceeds the individual’s threshold, that agent takes action.

Of central interest to Epstein is the case where an agent not subject to any aversive stimulus nonetheless destroys innocent sites. As shown in Figure 5-1, Epstein studies this by fixing one occupying agent in position in the (nonviolent) southwest with all aggression (orange explosive sites) taking place in the northeast, far beyond the fixed agent’s vision. However, occupying agents in the northeastern region do experience attack and fear-condition on these violent stimuli. Epstein reported, “They’re also computing a relative frequency of [bad actors] within their vision to get an empirical estimate of [enemy prevalence] in their neighborhood. And when the sum of those exceeds their threshold, they wipe out sites. And because they are connected to [the fixed] agent [through inter-agent weights], he also wipes out sites despite never having any aversive experience at all.” The mechanism, moreover, is not imitation of observed behavior, but rather what Epstein dubs “dispositional contagion.”4

Even more arresting was Epstein’s later example of an agent who is subject to no attacks, but who nonetheless leads the retaliation. The agent ends up as the first to destroy sites because of dispositional contagion, whereas left to his own devices, he would not have attacked at all, said Epstein. Epstein pointed out that the important feature of the mathematical equation guiding the simulation is dispositional contagion, not imitation of overt behavior: that is, no agent’s binary action appears in the governing equation.

Epstein reviewed some neurocognitive underpinnings of the model, emphasizing fear through activation of the amygdala. This machinery is considered to be innate, automatic, fast, and inaccessible to deliberation. He noted that humans have the capacity to fear condition on what would otherwise not be salient (noticeable) stimuli. He pointed out that there are simple ways to create fear conditioning: for example, exposing one repeatedly to a stimulus (a blue light, for example), which is immediately followed by a shock or other painful experience. One begins to fear the appearance of the (painless) blue light. Epstein noted that fear conditioning is emulated in the model as agents associate particular indigenous sites with an adverse stimulus, such as an ambush. The binary act (retaliation) then mimics an automatic neural process and an unreflective response.

Epstein pointed to the literature on the social transmission of fear without direct stimulus as the basis for modeling fear as contagious. He also noted that when agents in the model take action based on the local

___________________

4 The webcast of Epstein’s presentation, including an animation of the “Slaughter of Innocents” scenario discussed here, can be found at http://sites.nationalacademies.org/DBASSE/BBCSS/DBASSE_173737 [January 2017].

relative frequency of bad actors, they are emulating two well-documented cognitive errors (reliance on the representativeness heuristic and base rate neglect). In addition, the model is built, according to Epstein, on the neuroscience of social rejection and attendant conformist pressures. In the model, conformist pressures (to avoid the pain of rejection) produce widespread convergence on counterproductive behavior (i.e., the alignment of affect produces connection and strengthens it).

He illustrated several published extensions of the model, including actions to flee (rather than destroy) an adverse situation, noting the relevance of this to refugee dynamics.5 There are also instances of corrupt regimes and citizens’ reactions, as well as jury trials and collective decisions, each with different sets of binary actions. These include model runs where no jury agent would convict on its own, but they unanimously do so under dispositional contagion. Epstein called this a case of “universal self-betrayal.”

Epstein concluded his presentation by reiterating that the Agent_Zero model should be deepened, scaled up, and calibrated with real data. His goal is a neurocognitively grounded formal model capable of generating important social phenomena, to serve as an explicit functional alternative to the rational actor and as a foundation for generative social science.

STEREOTYPING AND NATIONAL SECURITY

Susan Fiske reviewed evidence that simple principles of stereotyping are correlated with national inequality and also with a national peace conflict index. She reported that stereotypes operate on two dimensions that appear to be universal across the several dozen societies that her research program has studied: these dimensions are warmth (trustworthy, friendly) and competence (capable, effective). According to Fiske, the combinations of these two dimensions go beyond the notion of just simple good/bad stereotypes; that is, a group stereotype might be high or low on both dimensions or might be high on just one and low on the other. The latter combinations (high warmth/low competence or low warmth/high competence) are considered ambivalent combinations of stereotypes, and according to Fiske, they can be crucial for distinguishing countries. Fiske explained that societal variables predict this ambivalence.

Fiske defined the dimensions that are needed to be known about an unknown individual or group. First, are they friendly (warmth dimension) or are they antagonistic? Second, are they able to act on their intentions

___________________

5 Extensions of the model can be found in Epstein, J.M. (2013). Agent_Zero: Toward Neurocognitive Foundations for Generative Social Science. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

(competent) or not? Fiske has collected cross-national data6 from dozens of countries and found that poor people all over the world (e.g., refugees, asylum seekers, homeless people, and immigrants) fall into the low/low quadrant, viewed as low on warmth and low on competence. Notably, in her research, people report feeling disgust and contempt toward these people. In contrast, a society’s particular reference groups tend to fall in the high/high quadrant; in most countries, according to Fiske, this reference group includes that country’s citizens and middle-class people.

Across societies, Fiske reports that groups seen as well-intentioned but incompetent include older people and people with disabilities, and groups seen as highly competent but cold include rich people and elite professionals. She provided an example from U.S. data: using the group as the unit of analysis, the researchers subjected the data to cluster analysis and plotted the means in a high warmth/low warmth and high competence/low competence 2×2 grid. For U.S. data, stereotypes of middle-class people, blue-collar workers, Christians, and white people fall in the high/high quadrant; stereotypes of poor people and teenagers fall in the low/low quadrant; stereotypes of children and old people fall in the high warmth/low competence quadrant; and stereotypes of rich people and to some extent Asian and Jewish people fall in the low warmth/high competence quadrant. Fiske pointed to groups clustered in the middle, neutral space (black people, conservatives, atheists, and Muslims), noting that stereotypes for these groups differentiate by subtypes within the groups.

Fiske reported that early in her group’s research, samples produced a fair amount of ambivalent combinations, and no correlation appeared between warmth and competence. Beginning with samples from Switzerland, a high warmth/competence correlation emerged. In this case, there were less ambivalent combinations, and Fiske and her colleagues credited this to Switzerland’s “big social safety net” to support a more inclusive ingroup (all citizens including unemployed people and people with disabilities) but still some extreme outgroups (e.g., asylum seekers). Scandinavian countries show a similar pattern of positive “us” and a few negative “them.” In contrast, other countries (such as South Africa, Mexico, and the United States) show more ambivalent stereotypes. Eventually, the research was extended to Middle Eastern countries with high conflict, where interesting patterns of low ambivalence stereotypes were observed.

Fiske reported the research, then looked at macro-level variables such

___________________

6 The standard method of collecting data in Fiske’s research program is to have a sample of about 30 to 50 adults nominate their society’s groups. In the second phase, a larger sample rates 16 to 30 groups. Because there is considerable consensus, noted Fiske, only 60 to 100 adults need to be surveyed to provide a stable estimate of ratings on groups. The group becomes the unit of analysis.

as the Gini coefficient of income inequality, gross domestic product (GDP), the total number of groups in the society, and power distance. She and her colleagues found that the warmth/competence correlation correlates with the Gini coefficient but is not moderated by the other variables. That is, she explained, inequality predicts more ambivalence, as if those nations have more to explain. The research uncovered a pattern, according to Fiske, that countries with more moderate peace-conflict showed more ambivalence in stereotypes, but extremely peaceful and extremely conflictual countries both show less ambivalence in stereotypes.

In closing, Fiske noted that the content of stereotypes fits with an overall causal model to guide future research—a model in which social structure, competition, and status between groups in a society predict these images of warmth and competence, which in turn predict emotions toward groups, which in turn are the precursors to behavior.

CHANGING TRENDS FOR A FUTURE WORLD

Mathew Burrows reflected on the differences between the kinds of issues considered today compared with those considered or anticipated in the past. Burrows reported that from the 1990s into the beginning of the 21st century, four key assumptions seemed to be backed by data and societal trends. He pointed out that those assumptions have changed in the past 5 or 6 years.

According to Burrows, the first assumption considered that as part of integration or globalization, rising states would join the western order, largely because of the benefits that could be derived from doing so. The second assumption was the belief that there would be ideologies or differences of opinion, but not on the same scale that existed before the end of the communism-against-capitalism era. The third assumption took a positive economic outlook and considered that the vast majority of technological changes would be very positive and increase productivity. The fourth assumption was the belief that conflicts would die down.

Burrows referenced a paper on global inequality that points out that middle classes in the West have not kept up in terms of income increases.7 Globally, the proportion of middle-class consumption is increasingly situated in the East and the South. He noted an increase in educational attainment worldwide and a closing of the gender gap, with more young girls having the same opportunities as young boys.

___________________

7 Khara, H., and Gertz, G. (2010). The new global middle class: A cross-over from west to east. In L. Cheng (Ed.), China’s Emerging Middle Class: Beyond Economic Transformation. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press. Available at https://www.brookings.edu/wpcontent/uploads/2016/06/03_china_middle_class_kharas.pdf [January 2017].

The aging of societies, according to Burrows, was not even considered 20 to 30 years ago, but is now a big concern as spending on pensions and health care goes up. In the United States, health care costs are a much higher percentage of GDP (18 percent) than in other industrialized countries (10 percent). Burrows said this issue could affect national security as discretionary spending in federal budgets decreases. He presented information and statistics to show that the growing labor pool and productivity was responsible for economic growth in the 1950s through 1970s, but today U.S. economic growth is being challenged because of an aging population.

On the notion of ideologies, Burrows pointed out that the growth in democratic societies is plateauing. He also noted that the degree of attraction of jihadism within populations in Western societies, although not a predominant threat, was surprising. On technology developments, according to Burrows, concerns about the costs of cybersecurity have begun to outweigh expectations of productivity gains from emerging technologies.

In terms of conflicts, Burrows recognized that the nature of conflicts has changed but not disappeared. Notably, intrastate conflicts have increased. These types of conflicts often last 6 to 9 years and are very difficult to end with durable peace. Additionally, Burrows reported on the concern about the reemergence of state-on-state conflicts.

In closing, he identified the likeliness of four possible states of the world. He thought a “reinvigorated West” and a “new global concert” were the least likely conditions to emerge. He thought a “breakdown into blocs” was most likely with evidence to the increasing trade within regions and ongoing talk about the fragmentation of the Internet. The “new bipolar cold war” is also a possibility looking over a 10- to 20-year time frame, according to Burrows, which would position Russia, China, and others against the United States and its partners.

DISCUSSION

George Gerliczy (Central Intelligence Agency) offered comments from his perspective in the IC. He observed that the IC has a growing interest in a broader set of societal issues. Traditionally, the IC developed around specific threats focused on the leadership and military capabilities in specific countries. Gerliczy noted increasing focus on leaderless movements and societal issues along the lines of contagion, collective action, and diffusion.

Gerliczy’s second observation related to formal models. He noted the bar is high for using models, particularly if they are not sufficiently transparent. Their use requires buy-in from fellow intelligence analysts and the ultimate customers or policy makers. He said he has had positive and negative experiences with models. In the situations where a model worked well, according to Gerliczy, the analysts (and sometimes policy makers) could ask

questions of the model developer on the track record of the model, how the model is calibrated, and whether applying the model to a new situation is interpolating or extrapolating. Ultimately, Gerliczy noted, the model must prove valuable in terms of the practical insights generated.

Valerie Reyna (Cornell University) asked the panelists to consider how a model that described what currently existed might adapt to changing social conditions. For example, in a model of social structure and outcomes, increasing the education of women would change the social structure in some societies, which could change the images, which could change the emotion, and therefore change the outcomes. Fiske responded that her research program has another model about gender bias, which is predicated on ambivalence. In many societies, traditional women are seen as warm but not competent, and nontraditional women are seen as competent but cold. Additionally, she has found that an individual difference measure of people’s beliefs in hostile or benevolent sexism correlates with United Nations indices of gender development.

Mitzi Wertheim (Naval Postgraduate School) pointed out the need to understand different cultures better and to learn from work in the field of anthropology. She referenced a book by Jim Clifton, The Coming Jobs War, which called attention to the global problem of large populations of young men without job prospects.8

Fiske asked Burrows whether an inflow of young immigrants who work and contribute to Social Security, but do not draw on it, can offset some decline in economic growth. Burrows reported that in a study conducted in Germany, modeling showed delay on the impact of the aging population by about a decade if Syrian and other immigrants were integrated successfully and performed at the same productivity levels as German workers. He said he recognized that this raises an important point in how discussions about immigration are framed and integrated with other issues.

Irene Wu (Federal Communications Commission) asked Epstein whether the Agent_Zero model can be used to understand someone who is not committing violence but instead trying to organize communities. She noted cases where people unconnected with certain events are able to collectively organize a protest or movement through social media. Epstein agreed his model could apply to this scenario. He explained that the self-organization of groups identifying with one another is the mechanism of network formation in the model and, furthermore, that his work is interested in both the construction and dissolution of networks. He also commented on resilience. A single bullet, he said, might stop a bear, but does not work against a bee swarm because the swarm reconstitutes itself and is resilient to local disruption. He suggested that in situations of extremist

___________________

8 Clifton, J. (2011). The Coming Jobs War. New York: Gallup Press.

network formation, perhaps a strategy for dissolution would be to enable a decentralized immune reaction.

Epstein suggested that there was no escaping modeling, even for people who are skeptical of models. People naturally have mental models, he said, even if they are implicit models where the assumptions are not made clear. He also pointed out the difference between explanatory and predictive models. For example, plate tectonics explains earthquakes but cannot predict them. Epstein said, “A lot of social science is about identifying the fundamental drivers of social dynamics, even if . . . what will happen tomorrow [cannot be] predicted. These drivers could [help] detect signatures of instability. . . .”

Gerliczy responded with a caveat that some intelligence analysts associate models with things that are high cost and low payoff. Sometimes it has to do with implementation of models in the past, he commented. Fingar pointed out that far too much information is collected, and irrelevant data are often analyzed. He suggested that models be used to consider which data should be examined.