7

Fourth Research Session: Risk and Decision-Making

The fourth research panel was moderated by Sallie Keller (Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University) and showcased cutting-edge work in the area of decision sciences and risk. Panelists included David Broniatowski, assistant professor in the School of Engineering and Applied Science at George Washington University; Paul Slovic, professor of psychology at the University of Oregon; and Jeremy Wolfe, professor of ophthalmology and radiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School. Each panelist presented an overview of his research program and highlighted key findings, methodologies, data considerations, and relevance to the work of analysts in the intelligence community (IC).

COMMUNICATION STRATEGIES FOR BEHAVIOR CHANGE

David Broniatowski focused on what military doctrine calls the “battle of the narrative,” which involves communications strategies for behavior change, specifically on social media. His presentation explored the implications of communications strategies for national security and for public health and synergies between these fields.

Broniatowski illustrated directives from military doctrine on the importance of narratives. For example, Field Manual 3-24, the Counterinsurgency Field Manual,1 emphasizes the ways that insurgents and counterinsurgents might use narratives to attempt to mobilize populations for good or for ill.

___________________

1 Available at http://usacac.army.mil/cac2/Repository/Materials/COIN-FM3-24.pdf [January 2017].

Joint Doctrine Note 2-13 emphasizes the role of social media, in particular as a medium for the rapid transmission of information and misinformation and how social media can be something that is used to motivate populations to take actions, whether for good or for ill.

On the importance of narratives, Broniatowski highlighted a quote from a special issue of Vaccine2 in the context of vaccine refusal: “Narratives have inherent advantages over other communication formats. They include all of the key elements of memorable messages. They are easy to understand. They are concrete and credible. And they are highly emotional. These qualities make this type of information highly compelling.” He said that compelling narratives are generally assumed to lead to behavior change.

Broniatowski presented statistics to illustrate that more and more people receive their news and information from social media. For example, 80 percent of Internet users seek information about their health online. Sixteen percent seek information about vaccines online. Among millennials, 61 percent get most of their news from social media. Calling attention to Facebook, he noted that 81 percent of all article shares are Facebook posts, and 71 percent of all online U.S. adults are on Facebook. He suggested that this major social media platform may be responsible for informing a significant portion of the U.S. population.

In considering the role of narratives in public health, Broniatowski drew attention to well-organized antivaccine campaigns that often exploit the use of social media. He noted that these campaigns generally make use of decontextualized facts, manipulating them to fit an existing narrative. A common approach is to present sequential events as if they are causal conclusions, when they are really spurious correlations. Broniatowski illustrated this approach with an example about the Zika virus. He noted that a recent report, released in South America, claimed that Monsanto’s release of the larvicide pyriproxifen, not the Zika virus, was responsible for microcephaly. According to Broniatowski, the report had a number of factual inaccuracies, but it became a major anti-Zika story for a short period of time.

Earlier this year, he conducted a study analyzing tweets about the Zika virus, identifying the posts that contained pseudoscientific claims and examining the characteristics of the people transmitting these pseudoscientific tweets. He found that about 85 percent of them had previously tweeted about vaccines within the previous year. A majority of these people, at least 57 percent, had previously tweeted a similar antivaccine message. He determined that although the context was different, some people with an

___________________

2 See Betsch, C., et al. (2012). Opportunities and challenges of Web 2.0 for vaccination decisions. Vaccine, 30:3730.

antivaccine message seemed to put together new information into an existing narrative. According to Broniatowski, the social media conversation became an issue of great public health concern when a significant number of people seemed to buy into the idea that Zika was not causing microcephaly.

Broniatowski introduced the concept of fuzzy trace theory to help explain why some of these claims are compelling and what is driving some of these behaviors. Fuzzy trace theory, a leading theory of decision under risk, posits that there are two types of memory: (1) verbatim memory or memory for precise details, such as statistical figures; and (2) memory that encodes the basic meaning or the gist or bottom line of an idea. According to Broniatowski, research has shown that people tend to make decisions based on gist memories preferentially when compared to verbatim memories. He pointed out that fuzzy trace theory predicts that stories are going to be effective because they communicate a gist. He suggested that websites that produce coherent or meaningful gists that cue relevant moral and social principles will be more influential and compelling than websites with a lot of decontextualized or unstructured factual information.

Broniatowski shared results from another study he conducted to test fuzzy trace theory. About 4,500 articles published between November 2014 and March 2015 related to the Disneyland measles outbreak were coded as to whether they contained statistics about viruses or vaccines, whether they contained a gist or bottom-line meaning, and whether they contained a story. The study also measured how frequently these articles were shared on Facebook. It found that articles with a gist were significantly more likely to be shared than articles that did not express a gist. Articles with a gist that mentioned both sides of the vaccine debate were about 58 times more likely to be shared than articles with a gist that did not mention both sides.

Broniatowski is now working on a gist communication framework. The steps of the framework include communicating the verbatim (evidence, research findings), then linking the evidence to a bottom-line meaning or suggestion for one’s actions. He drew attention to the need for cultural sensitivity when relating the evidence to something of value to the audience. He explained that this means understanding the values and norms of the communities in order to effectively communicate with them.

In closing, Broniatowski offered ideas for future research directions that can increase understanding of these values and norms. Specifically, he is exploring how data can be collected from social media in a synergistic fashion with existing survey techniques. He expressed the hope that the same norms and practices that now characterize rigorous survey sampling can be developed for sampling across social media platforms. He suggested that data from social media could complement survey data in a number of ways, reducing the speed of sampling as well as the cost and oversampling the

populations that surveys undersample. Analysis of social media data may also lead to pretesting hypotheses before developing more in-depth surveys.

PSYCHOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVES ON NATIONAL SECURITY

Paul Slovic reviewed five different domains of interest to national security and illustrated how they can be studied systematically with a behavioral orientation:

- perceived risk of terrorist attacks,

- economic impacts of these risk perceptions,

- risk communication strategies for increasing resilience after a terrorist attack,

- development of a strategy for deterring unstoppable terrorist attacks, and

- consideration of the question of whether humanitarian values collapse when they conflict with national security objectives.

Slovic pointed out that risk perception has been studied systematically for decades. Research has sought to understand how people interpret risk, the factors that determine their perception and acceptance of risk, the role that emotion and reason play in risk perception, and the social and economic implications of these perceptions. Within the context of terrorism, the research questions have included how perceptions of terrorism risk compare to disasters and other accidents; how different types of terrorist activities/actions compare with each other; how risk perceptions can be used to forecast the impacts that these events will have on society; and whether risk communication strategies can reduce harmful social, political, and economic overreactions to terrorist attacks.

In studying perceived risk of terrorist attacks, Slovic’s research program has used hypothetical damage scenarios that involve terrorism and non-terrorism events. In either case, the damages were the same in terms of harm to people attending a theme park in Southern California, the mechanism was either explosion or disease. In addition, the scenarios varied by the motive of the attackers and the victims, such as whether the attacker had a suicide intent or whether the victims were visiting officials or tourists. The number of people who were killed in an event ranged from 0 to 495. Slovic presented a short story line of an attack at a theme park to illustrate an example of a scenario. Keywords varied from one story to another to change the context of the event. Slovic reported that the keywords were systematically manipulated within the standard scenario frame in order to assess how they affected the dependent variables, which were based on a questionnaire about risk perception, trust in officials, and the like. He

indicated that study subjects were also interviewed about their behaviors, such as whether the damaging event would stop them from going to theme parks or outdoor places in general.

Slovic reported findings from the research. The research subjects perceived the anthrax and bomb scenarios defined as terrorism as much higher risk than the same level of damages done through a propane explosion or infectious, non-anthrax disease. Subjects were more worried about anthrax than a bomb, which he surmised is, in part, because a bomb is more defined in space and time than anthrax. Another finding was that terrorism events compared to other events with the same damages were associated with greater perception of risk, less trust in first responders, greater trust in government officials, and less confidence in the ability to protect oneself. Other noted behaviors with terrorism included more attention to the news media and greater perceived need to contact friends and family.

Slovic also sought to quantify the impacts of different types of events within a conceptual framework that asserts that risk perceptions drive behaviors that can have enormous social, economic, and political impacts after a terrorist attack.3 In one study, subjects were interviewed about their response to a hypothetical but realistic scenario: a dirty bomb explosion in the financial district of Los Angeles that scattered radioactive material around several blocks in the downtown area but was cleaned up over time. Subjects were asked if they would work in, shop in, or visit this area. Slovic worked with economists to assess economic costs of the different reactions. The research found that the indirect costs driven by behavioral reactions due to fear and the stigmatization of the attack location may be far greater than the direct costs associated with the physical damages—an estimated 15 times greater than the direct damages in one case that was studied. He noted the cost multiplier would vary with event and context and suggested that further research could help identify what factors associated with a terrorist attack would trigger greater or lesser impacts.

In regard to risk communication strategies, Slovic referred to research on a concept borrowed from social psychology called inoculation messaging, which can be used to prepare people in advance for an event by giving them a brief exposure to the possibility, analogous to a vaccination. A sample message might be, “These attacks will happen. The officials have prevented many such attacks. They are doing a lot of things that are competently working to minimize these attacks. The intent of terrorism is to disrupt lives and society. They want you to overreact, etc.” In one study of inoculation messaging and responses to a terrorist event, the research found

___________________

3 A theory called the social amplification of risk, designed principally by Roger Kasperson and colleagues. See Kasperson, R.E., et al. (1988). The social amplification of risk: A conceptual framework. Risk Analysis, 8(20):177-187.

that the group that received the inoculation message had a very strong and somewhat lasting effect of a much more restrained response, with less loss of confidence in officials, than was found in a control group that did not get the message. Slovic recognized it was only a single study, but felt it illustrated the possibility that communications can be used strategically to make society more resilient to these attacks.

Slovic then referred to findings from research that might be used to help understand what might demotivate people from committing attacks. Potentially important insights were found in studies examining how to motivate people to help others in need, such as children facing starvation in various countries. This research found that nonrelevant sources of negative feelings can create an illusion of nonefficacy that demotivates people from helping others even when they are capable of helping. He reported that the donations to a charity helping children in need dropped almost in half when the statistics of starvation were put in the same frame. Such a presentation, according to Slovic, made people feel bad by making them aware that although they could help one child, they could not help millions more. A similar loss of good feelings and less willingness to donate also occurred when the communications showed a small number of children that could not be helped or unrelated highly negative pictures such as a dog snarling, a shark baring its teeth, or a handgun. In sum, certain conditions created a feeling of nonefficacy in people who were capable of doing good things for the children.

Slovic and colleagues hypothesize that, in much the same way, a way to deter terrorists may be to create an illusion of nonefficacy, introducing cues or other stimuli that would diminish the perceived efficacy of what they were considering. He noted that research such as the studies of children described above, shows that emotions let in irrelevant sources of negative affect that can confuse capable people about their efficacy. He suggested that academics and security experts, including those with cultural and social knowledge about the populations from which terrorists come, work together to develop ways to use these insights to demotivate attackers from attempting to cause harm.

On his final point that life-preserving interventions are devalued when they conflict with national security, Slovic described three obstacles to responding to humanitarian crises: psychic numbing, pseudo inefficacy, and prominence bias in decision-making. He suggested that decision makers need to be aware of the subtle way that their decisions may contradict their expressed values through the overweighting of national security and the diminishing of the importance of protecting human lives. He suggested the use of well-regarded structured decision-aiding techniques in top-level decision-making. This approach induces decision makers to think more

carefully about the tradeoffs between conflicting objectives and brings expressed values and values implied by decisions into closer agreement.

HOW VISUAL ATTENTION LIMITS VISUAL PERCEPTION

Jeremy Wolfe considered the visual attention space of experts who are trying to detect threats. He noted that threats can be missed, not just in unmonitored or poorly monitored spaces, but also in well-monitored systems. He reviewed five psychological challenges that explain why threats are missed: profusion, spatial uncertainty, inattentional blindness, prevalence of a threat, and the ambiguity of that threat.

Wolfe recognized that the challenges of profusion tend to be obvious. Technology increasingly produces too much information for anybody or any group of people to monitor. For example, a chest x-ray used to be a picture with ribs on it. Now, advanced technology can produce hundreds or thousands of images from different orientations that cannot all be scrutinized at the same level by radiologists.

To illustrate spatial uncertainty, Wolfe showed the audience a picture of coffee beans with hidden faces and ladybugs.4 It was difficult for the audience to find all the faces and ladybugs that were scattered within and camouflaged by the coffee beans. Not knowing where to look makes a difference in one’s sensitivity to stimuli, he said. He also noted that people tend to miss a second target after one target is found, a phenomenon known as satisfaction of search. This happens even if the targets could have been found in isolation.

To illustrate inattentional blindness, Wolfe asked the audience to find a set of golf balls in a picture of a miniature golf course. Some golf balls were notably on the green, but others were in the trees. Wolfe called inattentional blindness a curse of expertise: that is, if people know where something should be, they tend not to look in unusual or atypical places. This learned behavior can be useful in many situations, such as knowing where to look for signs when driving down a highway.

In a research study of inattentional blindness, Wolfe inserted a small picture of a gorilla into an X-ray of a lung.5 He reported that 20 of 24 radiologists failed to report the gorilla. Although the radiologists were asked to screen for lung cancer, they were also supposed to keep an eye out for incidental findings. However, their experience and adaptive behavior allowed them to miss something significantly out of place. Wolfe queried why people

___________________

4 See, for example, http://www.moillusions.com/hidden-coffee-faces-and-bugs/ [December 2016].

5 See Drew, T., Vo, M. L.-H., and Wolfe, J.M. (2013). The invisible gorilla strikes again: Sustained inattentional blindness in expert observers. Psychological Science, 24(9):1848-1853.

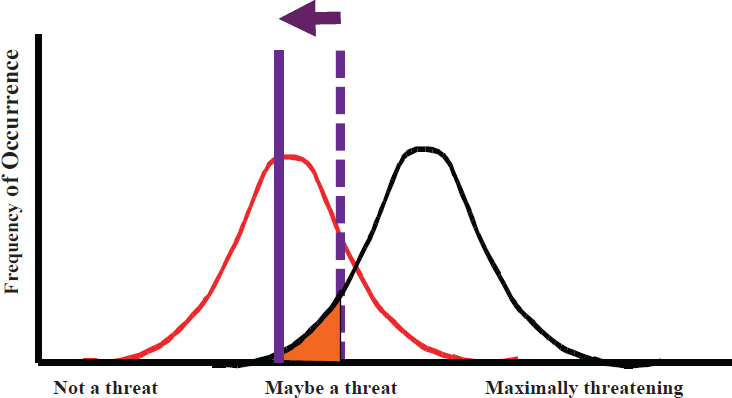

NOTE: Distributions of nonthreats and threats often overlap. If one needs to make decisions between threats and nonthreats, a criterion can be chosen (dotted line). If the error of missing a threat is unacceptable, the criterion can be moved to the left (solid line). However, this increases the rate of false positives or false alarms.

SOURCE: Adapted from Wolfe, J. (2015, October 5). How the heck did I miss that? How visual attention limits visual perception. Presentation at the Summit on Social and Behavioral Sciences for National Security, Washington, D.C.

do not see what is right in front of them. He used the word “gist” a little differently from Broniatowski, arguing that people see the gist, which he defined as a limited amount of semantic information about visual stuff in front of them. According to Wolfe, a person attends to and fully recognizes only one or maybe a very small number of objects at any one time. If something changes in the view for a moment but does not change the visual gist of the scene, a person likely will not notice it.

Wolfe pointed out that many visual searches are for rare or low-prevalence events, such as threats at baggage screening, cancer in breast cancer screening, and terrorist attacks. He noted that research has determined that threats or targets in a low-prevalence context are missed at a higher rate than threats or targets in a high-prevalence context.6

On the problem of ambiguity, Wolfe illustrated a continuum, in which

___________________

6 See, for example, Evans, K.K., Birdwell, R.L., and Wolfe, J.M. (2013). If you don’t find it often, you often don’t find it: Why some cancers are missed in breast cancer screening. PLoS ONE, 8(5):e64366.

some things are very clearly threats and others are not so clearly threats. Similarly, there are nonthreats and not-so-clear nonthreats (Figure 7-1). A decision boundary (or criterion) placed on the continuum could lead to correct determination of threats and nonthreats (true positives and true negatives) but could also lead to errors (false positives and false negatives). Wolfe pointed out that the choice of a decision boundary is a choice around which type of errors will be tolerated more.

In closing, Wolfe summarized that people’s visual systems have limited capacity. He recognized that technology is expanding the amount of visual information that could be considered. He reiterated that targets can be missed in a search if they are rare occurrences or ambiguous. They also can be missed if in unusual locations. Wolfe suggested that future research further explore people’s limitations and examine countermeasures.

DISCUSSION

George Gerliczy (Central Intelligence Agency) noted Broniatowski’s presentation mentioned pseudoscientific claims, which reminded him of conspiracy theories. He pointed out that the CIA is often the target of conspiracy theories and, therefore, the theories are of great interest. He provided an example of working with academic experts to develop an analytic framework to help think about conspiracy theories. The academics were asked to consider factors that make people either more likely to believe in or more likely to spread conspiracy theories. He noted interest on three different levels: (1) individuals—what is it that makes them more or less likely to embrace conspiracy theories? (2) groups—what does the group interaction look like? and (3) societies or culture—what makes a large group generally more or less likely to embrace conspiracy theories? The academics also provided advice on countermeasures, some of which were counterintuitive.

He said the intelligence community is interested in knowledge about risk perception and reactions to risk at the levels of individuals or leaders, organizations, and broader society. He emphasized that the CIA focus is overseas, but other IC agencies with a domestic mandate may be more interested in domestic applications to build societal resilience to risk and mixed messaging.

Slovic observed that in regard to the importance of gist, narratives may oversimplify complex situations, which can lead to actions that on more careful reflection might not be taken. He pointed to research on imperatives, which he defined as seemingly self-evident statements that guide decisions. Research examined Lyndon Johnson’s decision to expand combat in Vietnam based on the imperative to stop the spread of communism and George Bush’s decision to enter Iraq based on the notion that Saddam

Hussein had weapons of mass destruction. Slovic suggested that such compelling imperatives may make the decision seem obvious and thus, at times, can cut short careful analysis and deliberation.

With regard to Wolfe’s discussion of situations that overwhelm visual attention, Slovic pointed to his own research examining people’s willingness to help others. He found when a person has two or more people to consider, rather than just one, he or she is likely to feel less sympathy and less motivation to help them because the motivation to help is driven by attention, and his or her attention is spread among two or more people, limiting the development of an emotional connection to the people in need.

Steve Rieber (IARPA) asked Slovic to clarify whether he saw the secondary effects of terrorist attacks as an irrational overreaction, or as rational and perhaps even necessary to prevent a much larger subsequent attack. Slovic said his research found very strong reactions, with large societal costs, as secondary effects. However, he said, whether or not they are overreactions needs to be debated to determine appropriate levels of response and costs society is willing to bear to protect national security.

Charles Gaukel (National Intelligence Council) pointed out that in his experience, when faced with making decisions or judgments in situations of high uncertainty, people often resort to reasoning by analogy. He asked about the use of analogies—when people use them, when they are appropriate and when not, and the pitfalls and advantages. Slovic recognized a large research literature on reasoning by analogy. He asserted using an analogy could be a problem when it is too much of a shortcut in complex decisions with multiple objectives and cuts off more careful analysis.

Another attendee emphasized the importance of continuing to consider the issue of reasoning by analogy. The attendee noted that things can be similar in terms of superficial characteristics, or they can have deep similarities. Research has examined the use of analogies to improve decision-making by giving people simple appropriate analogies to reduce cognitive biases such as base rate neglect.

Stuart Umpleby (George Washington University) recognized that social systems, as opposed to physical systems, consist of purposeful actors, namely individuals and institutions, who tend to change their mind and behave differently at different times. He asked if the SBS Decadal Survey would consider expanding the conception of science so that it more adequately encompasses social systems. Keller responded that it probably would.

Broniatowski provided more information on the role of cultural sensitivity. When addressing a particular conspiracy theory or pseudoscientific claim or any claim, Broniatowski noted it is important to understand how that gist interfaces with a person’s cultural background, which is ultimately the gist to that person. For example, in the antivaccine debate, according

to Broniatowski, when it was believed that thimerosal in vaccines caused autism, the CDC response and message was to remove thimerosal from the vaccine. Antivaccine supporters changed their narrative to that in which autism is caused by other toxins present in vaccines. Broniatowski suggested that the high-level gist for this group is that the government is trying to poison citizens and cannot be trusted. He noted that these claims, now incorporated into some people’s worldviews, can come from legitimate sources, such as history related to the Tuskegee syphilis experiments. He summarized that if a narrative focuses on specific findings and statistics, the bottom line is open to interpretation of those findings through whatever lens a particular community may be using. He proposed that there would be value to speaking specifically to a gist that a community understands backed up by facts.

A summit attendee asked Broniatowski to follow up on the characteristics of online antivaccine supporters and any intervention strategies. Broniatowski noted that studies of the antivaccine campaigns have found some hard-core supporters but a much wider range of people who are simply vaccine-hesitant. The emphasis is to intervene with those who are vaccine-hesitant rather than necessarily targeting the people who have a strong commitment to their opposition. The research field, according to Broniatowski, is looking to identify particular online networks, following the patterns and links of social media communications.

Gerliczy recognized that the nature of the work in the IC is much like that in health care, in terms of grappling with risk and uncertainty, high stakes, volume of information, and the regularity in which decisions are made. One difference, according to Gerliczy, is the amount of disinformation and misinformation. IC analysts often have to discern whether information offered or collected is informative or distracting. He acknowledged that any research or knowledge that can help improve the way in which the IC processes information to make sound decisions would be helpful.

Wolfe pointed out that one advantage of medical searches is that diseases typically are not trying to hide. Almost all IC-related threats keep changing. When the rules of a situation change, it takes a while for the analytic expertise to adapt. He suggested the IC needs to consider whether its training is responding to last year’s threat.

Mitchell Mellen (Office of the Director of National Intelligence) asked Wolfe about the implications for machine learning or deep learning to augment human perception. Wolfe said it depended on the task. If a machine can do the task at an error rate that can be tolerated, then it can be useful. He said, “A good breast cancer computer-aided detection system, for instance, will detect about 90 percent of the cancers and false-alarm about 10 percent of the time, which is on the order of what an expert radiologist will do.” If there are 1,000 cases, 3 with cancer, the system would identify

all the cancer cases but also false-alarm 100 times. This false-alarm rate might be tolerated in order to catch the 3 cases with cancer. By analogy, he said, a suggestion of 3 good restaurants for every 100 bad ones would be less appreciated. Wolfe pointed out that an understudied problem is the interaction of computer systems with the human expert.

Claudio Cioffi-Revilla (George Mason University) asked the panelists how they developed their sense of what is important and relevant for the purpose of intelligence analysis. Wolfe responded that the most useful tool is to have access to the relevant domain experts. “There is nothing like sitting with baggage screeners or radiologists or image analysts . . . and listening to what they [say] they are doing,” he commented. The challenge is time, he added: practitioners and analysts are busy and cannot be accessible for all the work that would be interesting in the research lab.

Broniatowski pointed out that he worked for a small defense firm before becoming an academic. Trying to make research relevant to the IC, he said, is a process of self-correcting through experience and feedback from the people who may find the tools or information useful. Gerliczy articulated that the IC, as part of the SBS Decadal Survey, is committed to engagement with academics to help bridge the gaps.

A webcast participant asked about any studies within the IC on group decision-making or processes. Gerliczy reported on work to understand how to make better decisions internally. There have been particular emphases after significant events. These efforts, according to Gerliczy, have been geared around mitigating the biasing effects of judgment and decision-making heuristics.

A second webcast participant asked Wolfe to identify any workarounds and countermeasures to address attentional bottlenecks. Wolfe pointed out that a straightforward workaround is to put more eyeballs or more cognitive systems onto the same problem (i.e., independent sets of analyses). Another way is to have an initial filter that narrows down the task to what should be examined or might be suspicious without worrying about false-alarm errors. This cuts down the profusion of spatially uncertain stimuli, and then a smaller set is analyzed.